Summary of Queer Art

Any art that can be considered "queer" refers to the re-appropriation of the term in the 1980s, when it was snatched back from the homophobes and oppressors to become a powerful political and celebratory term to describe the experience of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people. Adhering to no particular style, for over more than a century, Queer Art has used photography, portraiture, abstract painting, sculpture, and collage to explore the varieties and depths of queer identity.

While homosexuality has a long history, the modern sense of the term is relatively new. Since the late 19th century, cultural and legal responses to homosexuality have evolved, but it was only in the second half of the 20th century that many of the laws criminalizing homosexual acts were overturned. It wasn't until the late 20th century that homosexuality was no longer considered a pathology by psychiatrists, and it wasn't until the 21st century that marriage rights were granted to same-sex couples. Throughout all of these circumstances, Queer Art has addressed these issues covertly and overtly, insisting on a voice in the art world that routinely suppressed it.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Because of the early criminalization of homosexual acts and the social stigma connected to homosexuality, much Queer Art employs coded visual language that would not arouse suspicion among the general public but would allow those familiar with the tropes of the subculture to glean the hidden meaning.

- With the rise of activism in the wake of the Civil Rights protests and the AIDS epidemic, Queer Art became more frank and political in its subject matter, forcing the viewers to recognize queer culture and to underscore the institutional inequities and hypocrisy that fueled homophobia.

- The Identity Politics surrounding Queer Art has sparked much debate, with some artists embracing Identity Politics and other eschewing it as not important for their work. The shifting nature of identities in particular and changing contexts has induced much questioning in queer communities and produced a myriad of answers.

Artworks and Artists of Queer Art

Self Portrait

In this carefully posed Self Portrait the artist sits on a chair with legs crossed, facing the viewer. Dressed as a weightlifter, Cahun holds a dumbbell. Nipples drawn on the long-sleeve top give the impression that Cahun is bare chested. Written across the artist's shirt are the words: "I am in training. Don't kiss me." This deliberately and playfully contradicts the lips drawn beneath the assertion, the hearts Cahun painted onto the leggings and cheeks, and the painted, puckered lips. Cahun expression is camp, playful, and the posture is jaunty.

Born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, the French photographer, writer and political activist chose the name Claude Cahun after a number of different iterations before concluding "neuter is the only gender that always suits me". With gender playing such a huge role in how we understand ourselves in society, transgender variance is an important subject for Queer Art. Before the late-twentieth century, non-binary identities are hard to spot or understand, but Claude Cahun changed all that, creating, along with partner Marcel Moore, a subversive body of work that explored new possibilities for gender, sexuality, and personal identity.

French writer and Surrealist André Breton recognized Cahun as "one of the most curious spirits of our time" in the way Cahun rejected categorization as either a woman, lesbian, or artist. Cahun consciously played with masculine and feminine stereotypes to destabilize accepted gender norms. In the portrait series Cahun transmutes from one version of herself to another, bringing both personal and political agency that has traditionally been denied to marginalized groups.

Cahun died at the age of 60 and fell into obscurity but was rediscovered in the 1990s. Alex Pilcher explains, "A generation schooled in queer and postmodern thought rushed to embrace the forgotten artist as a prophet. Though Cahun's literary works and surrealist constructions are impressive, the artist's cult following is a response to the extraordinary self-portraits in which genders are swapped and mixed. This 'weightlifter' photograph has become one of the most revered (and regularly impersonated) queer icons of the twentieth century."

Photographic print

Medallion (YouWe)

This double portrait shows two women's faces in profile. The gray background gives the piece a powerful, somber tone. All that is visible beyond the head and shoulders of the figures is a low, green horizon. The artist is in the foreground, her focused and intense expression clearly one of a painter at work. Her hair is dark, cropped, and masculine. She wears no makeup or jewelry. Behind her and looking up as if to the stars in the darkening night is her lover, Nesta Oberma. Her profile, highlighted and tempered with a brighter palette mirrors the artist. The composition evokes a sense of strength, power, and permanence.

Gluck was born Hannah Gluckstein, but she built an androgynous identity by insisting upon "no prefix, suffix or quotes" around her gender-neutral name. The painter, who became known for her still lifes, portraits, and landscapes, defiantly rejected societal pressure by wearing fastidiously tailored men's clothes and closely cut hair.

Medallion was a radical portrait to release in 1936. The artist referred to it as the couple's "marriage" picture, decades before gay marriage would become an accepted norm. She called the public declaration of love her "YouWe" picture, adding, "Now it is out and to the rest of the Universe I call Beware! Beware! We are not to be trifled with." But the significance of the work was not discussed at the time. Male homosexuality was a criminal offense and there was no acceptable vocabulary for being lesbian or transgender. As Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord suggest, "Importantly, the painting's focus on their heads not only romanticizes the merging of two like spirits but also restricts the field of signifiers of lesbian visuality."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Two Figures

In this work, whitish-blue bodies wrestle on top of rumpled sheets. The powerfully rendered male figures are bulky and rawly expressed. The power of movement is emphasized by the minimal black background, and the dynamic brushwork around the faces distorts the men's expressions, leaving it hard to tell whether their faces are twisted in expressions of pain, anguish, or rapture.

This piece was among the darkest and most powerful of Bacon's work. It was inspired by late 19th-century photographs by Eadweard Muybridge of two men wrestling, but here the tangled sheets atop the bed make the homosexual meaning clear. This work was problematic for curators, and it had to be shown out of public view at London's Hanover Gallery, most likely due to the figurative hint of an erect penis. Later, police were called to investigate Bacon's work on grounds of obscenity. Howe says, "Bacon was probably aware that he was building upon aesthetic tropes of classical wrestling used since the nineteenth century as cover emblems of homosexuality.. The uniqueness of Bacon's approach to the subject is that he captured a moment of violent tenderness and intimacy through figurative rupture, the sensations and atmosphere of the clandestine sexual experience symptomatic of his own desire and time."

Much of Bacon's work was based on people he met in bars and clubs of London's Soho, an important locus for the queer community, and an area the artist called "the sexual gymnasium of the city." Bacon was an openly gay man, and as a teenager he was thrown out of the family home when he was caught trying on his mother's underwear. His autobiographical paintings provided a space where he could exorcise his demons; his life was shrouded in sadness, and in 1971, his lover of eight years, George Dyer, committed suicide in their shared hotel room.

The male nude was an important motif in Queer Art, as artists sought to present alternative versions of love and sexuality. In Bacon's work however, queer theorist Catherine Howe says, "The male body is both venerated and reduced to the status of animal; restricted yet liberated from societal conventions of desire." He would explore the wrestlers theme in different incarnations throughout the decades. The subject provided a perfect disguise for the sexual act, allowing the queer experience a respectable critical interpretation at the time.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

We Two Boys Together Clinging

In this work, two figures embrace in the center of the canvas, kissing as one's arm encircles the other. The abstract style robs the figures' gender, identity, and facial features to a certain extent, but script written around the two bodies reads, "We two boys together clinging." The paint marks are rough and expressive, contrasting with a calming color palette of blues, whites, rose pinks, and reds. Elsewhere around the canvas, words, numbers, and horizontal lines resembling an empty musical staff can be seen. The text suggestively appears to be graffiti on a public bathroom wall.

During a time when one had to be careful about openly sharing one's sexuality, Hockney described his work as "homosexual propaganda." His work was especially daring, as he explored notions of gay sexuality in painting before sodomy was decriminalized in the United Kingdom in 1967. Queer theorist Catherine Howe explains that Hockney often borrowed imagery from physique magazines, which while ostensibly about men's sports were catering to homosexual men.

This painting was produced at the beginning of Hockney's career and represents a marked difference from what would become his more realist style. The almost child-like technique was suggested to him by the French artist Jean Dubuffet. He produced it towards the end of his second year at the Royal College of Art. Hockney's work is a powerful declaration of independence; neither his artistic style nor his sexuality will be dictated. His British Pop art later provided a space where he could deliberately break rules, simultaneously deconstructing linear perspective along with accepted societal expectations.

Oil on Board - National Portrait Gallery London

Jim and Tom, Sausalito

In this photograph, two of Mapplethorpe's friends engage in a carefully staged and intimate sexual act. The man on the left leans back into the shadow as he urinates into the other's mouth. His face is concealed behind a gimp mask, while his penis is clear in the light. The man on the right is closed-eyed, submissive, kneeling on the floor. A shaft of light is carefully placed to highlight his face and his lover's penis.

Mapplethorpe's photography depicting still lifes of flowers, celebrity and Royal Family portraiture, and pictures of children are well-loved, but his powerful and subversive images of homoerotic subjects are most notable in their power to dramatically alter perceptions and push boundaries. Mapplethorpe, fascinated by the male gaze on the male body, brought underground queer culture of the 1970s and 1980s into the public eye. He produced provocative male nudes, explicit sex scenes, and erotic portraits of leather-clad men in sadomasochistic scenarios. It was work that captured social change in real life and brought the gay experience into the light for all to see - encouraging members of the gay community to come out of the shadows.

Mapplethorpe was central in the fight to make the queer experience recognizable as political identity, and his work was famously caught up in the Culture Wars when in 1989 the Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled a major Mapplethorpe show just weeks before it was due to start. Mapplethorpe politicized the physical body; he used images of the body to reassert his and other gay artists' right to exhibit images of the gay experience in public view. The value of this was made clear after the artist's death in 1989 from AIDS-related complications when US politician Jesse Helms said Mapplethorpe's work was a "threat to American values." His work highlighted the homophobia that reached into the highest ranks of American power.

Gelatin silver print - Los Angeles County Museum, USA

Gay Liberation

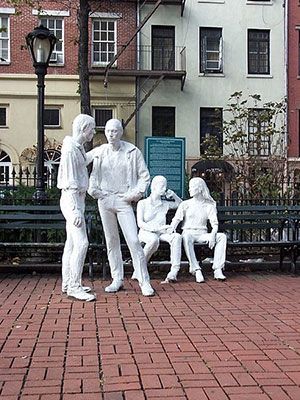

In this work, two life-size couples are relaxed in each other's company in the public space. A pair of men stand, talking casually, as one affectionately places his hand on the other's back. Nearby two women sit on a bench, one resting her hand on the other's thigh as they look eye to eye. The work is placed in a park, opposite the Old Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village and the site of the Stonewall riots in 1969 - one of the most important events in the gay liberation movement.

Using orthopedic bandages dipped in plaster, New York artist George Segal constructed haunting and memorable life-sized models which he seated at lunch counters, poised on street corners, or waiting in train stations. In doing so, he made sculpture that wasn't separated from the viewing public by a plinth or pedestal, allowing viewers a closer look and a more immersive experience.

While created in 1979, the work wasn't installed until 1992, and one made for Los Angeles was not accepted by the city. Critic Catherine Lord explains, "In 1980, 'public' signified audiences identified by race, class and ethnicity, rather than sexuality. At the time, gays and lesbians were seldom named as either producers or consumers of their own public culture."

The whitewashing effect of the work presents a blank canvas, onto which the viewer can add their own experience, but it also gives a ghostly feeling. The work caused consternation at the time as many felt the work should have been produced by a gay or lesbian artist. Detractors argued the whiteness of the sculpture suggested Caucasian individuals, thus whitewashing the role people of color played in gay liberation. Some also suggested that the anonymity of the figures depersonalized the very real stories of the people who fought for their rights outside the Stonewall Inn.

In 2015, the sculptures were vandalized (or improved - depending on one's viewpoint) when two of the figures were painted brown and wigs and colorful costumes added. The anonymous protesters said they did so in honor of the people of color who led the movement. "What we did was rectification, not vandalism. Those statues are bronze (brown) underneath the layer of white paint - the symbolism behind that is infuriating."

Bronze covered in white lacquer - Greenwich Village, New York

One Day This Kid...

A black and white image of the artist as a child looks out at the viewer. Smiling and innocent, the subject looks like any other ordinary child growing up in the 1960s. It is taken from a personal photo but blown up, newspaper-style, removing elements of intimacy and placing it within a political, public context. The figure is entirely surrounded by text that discuss the gay experience and the myriad ways society will attempt to oppress it. Statements that include "This kid will be faced with electro-shock, drugs and conditioning therapies in laboratories" paint a grim picture for the child's future. The words crowd him, filling the frame, oppressively at odds with the boy's youthful, optimistic expression.

The piece combines the personal and political in a powerful way that counteracts conservative representations of queer art of previous years. Newspapers and the right wing press had aggressively presented gay love as a dangerous perversion, particularly during the AIDS crisis. This piece however places it back in the realm of the ordinary, the final line reminding the viewer that gay love is as physical as heterosexual desire. The work's colorless composition and clear black text enabled it to be copied and shared widely, and it has since been circulated online and throughout bookstores across the United States and beyond. It has become a powerful icon for gay rights, a tool of activism, and one of Wojnarowicz's most well-loved works.

Curator Clare Barlow, says: "Queer theory of the early 1990s radically critiqued concepts of gender and sexual identity, and suggested new methodologies that privilege transgression, subversion and the unsettling of established norms." With this work we see Wojnarowicz flip notions of normalcy on their head to point the finger at a prejudicial and unjust social order powerfully stating that the problem is not with the child who is born genetically different from his peers but with an unjust society that persecutes difference.

Photostat mounted on board - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Melissa & Lake

Two women's bodies face one another as their faces turn to the camera. To the left stands a woman with cropped hair in a white shirt and black bow tie. She holds her partner's shoulder with one hand, while the woman in the green shirt clasps her waist. Their serious faces are half lit, giving the piece a dramatic feel, but they are in an ordinary domestic setting.

Catherine Opie, who has described herself as a "kind of twisted social documentary photographer," made a career exploring the world and people around her. This work was part of Domestic, a body of photographs she took during a road trip, to better understand the lives of ordinary lesbian American couples. Opie began her career shooting powerful and subversive portraits of cross dressing, sadomasochism, and the leather community. Later, she wanted to present ordinary pictures of queer life as a retort to the notion that the gay lifestyle was somehow deviant, and in doing so she produced insightful and intimate portraiture that has been wholly absent from mainstream media. In this way, her work aligns with the trajectory of Feminist art, whose goal, as artist Suzanne Lacy declared, was to "influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes."

Gender Trouble, Judith Butler's 1990 feminist text, sought to uncover the ways in which the very thinking of what is possible in gendered life is foreclosed by certain habitual and violent presumptions. She looked at how the gay experience impacted gender norms, asking for example, why do some butch lesbians who become parents become "dads" and others become "moms"? We see such questions at play in Opie's work, as she presents differing, subverted and updated images of gender, maternity, partnership, and domesticity.

Critic Liz Kotz wrote of Opie's work that "there is no text, no artist's statement, and a refusal to read and hence 'frame' these images for the viewer." Opie's social documentary, although produced out of a spirit to tell the stories of the oppressed and underrepresented, does not shout and confront like previous works of the genre. Rather it is quiet and inviting, asking the viewer to understand from a different experience the realities of universal notions of love and family.

Chromogenic photographic print - The Guggenheim Museum, New York

Beginnings of Queer Art

Before 1861, the death penalty existed for people convicted of gay sexual acts in England and Wales. Laws were slightly more liberal in parts of Europe, but in United States, those found guilty of sodomy could be punished by mutilation in some states. Such consequences meant that any references to homosexuality in art had to be heavily hidden. British art critic Laura Cumming explains how desires in early art could be easily spotted by those in the know: "Bee-stung lips, bare breasts, togas slipping discreetly from shoulders and eyes half-closed in ecstasy. By invoking the classical tradition of same-sex love, artists could paint Sappho embracing Erinna and David strumming Jonathan's harp and speak surreptitiously to particular viewers."

A discussion of the queer experience in relation to art history can begin in 1870 when for the first time a paper by German psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal considered the experience of "contrary sexual feeling" in which two people were dealing with what would later come to be known as homosexuality. Michel Foucault describes this as the birth of the homosexual as an identity, rather than a set of conditions. He wrote in the History of Sexuality (1976), "The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species," hinting at a future where the queer experience would become an important branch of Identity Politics.

Two-and-a-half decades later, in 1895, the British author and playwright Oscar Wilde was sent to prison for two years after he was convicted of sodomy, and the trials helped shape an emergent identity of the homosexual artist. An examination of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's portrait shows that the queer experience is not limited to people from homosexual backgrounds. While the subject of the painting is a homosexual artist, Toulouse-Lautrec himself was not, but his disability and height made him an outsider who could sympathize with Wilde's position. Art historian Richard Meyer explains, "As Lautrec's portrait suggests, the dialogue between art and queer culture cannot be confined to homosexual artists. Shifting constructions of desire and deviance have shaped modern art in ways that extend beyond sexual biography or individual preference."

Coded Art

Dismissive of the gay experience, history and criticism of the past deliberately concealed artists' sexuality. The Tate's Alex Pilcher writes, "Important biographical information about artists has too often been excised altogether, downplayed or else interpreted in terms that fit with a presumption of heterosexuality. The same-sex partner becomes the 'close friend.' The artistic comrade is made out as the heterosexual love interest....Be prepared to find gay artists diagnosed as 'celibate,' 'asexual,' or 'sexually confused.'"

A shift in culture began in the inter-war period as greater acceptance was seen in artistic urban centers. Paris and Berlin became home to literary groups where homosexuality was no longer seen as a sin. The roaring twenties saw speakeasies open in Harlem and Greenwich Village that welcomed gay and lesbian clients. Cafes and bars in Europe and Latin America, Granada, Moscow, Mexico City, and Warsaw became host to artistic groups which helped integrate gay men into mainstream cultural development.

Despite the increased openness of certain urban societies, the artists of the time learned to develop visual codes to signify queerness in clandestine ways, which were left open to viewers' interpretation. Art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon, for instance, said Jasper Johns' very famous monochrome encaustic White Flag (1955) was a statement about being a gay man in a restrictive American society. He wrote, "He was in a relationship with Robert Rauschenberg but if he admitted he was gay he could go to jail. With White Flag he was saying America 'was the land where...your voice cannot be heard. This is the America we live in; we live under a blanket. We have a cold war here. This is my America.'"

In 1962, the United States began to decriminalize sodomy, and in the United Kingdom by 1967 the new Sexual Offences Act meant consensual sex between men was no longer illegal. But societal pressures remained and many LGBTQ men and women faced intense pressure to remain "in the closets." Such pressures were exacerbated by actions of censorship such as the Hollywood Production Code which banned depictions of "sex perversion" from films made and distributed in the United States up until 1968.

Visibility

The Stonewall riots in 1969 changed everything. In the early hours of June 28, the New York City Police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay club in Greenwich Village. This action sparked a riot that turned into six days of protests and violent clashes which became the catalyst for the gay rights movement in the United States and across the world. This pivotal movement saw a shift in gay liberation, and people were encouraged to "come out" of the closets. Artists were inspired to use their work to discuss their sexual identity and to document and celebrate depictions of the queer experience.

The first Pride Parade was held a year after the uprising, and marches are now held every year all over the world. Placards and posters became an important tool as gay activist art sought to change the world. One such sign proclaimed, "I am your worst fear. I am your worst fantasy," positioning homosexuality as a site of both anxiety and fascination.

The AIDS Crisis and Culture Wars in the 1980s

Gay identity became the site of a new battle in the 1980s with the onset of the AIDS crisis. The deadly disease ravaged the gay and arts communities. Many artists became activists, demanding that their plights be heard by the government and medical institutions alike. On both sides of the Atlantic, right wing journalists and tabloid newspapers whipped up anxiety about the transmission of HIV by scapegoating gay men.

Controversy then erupted in the United States when certain conservative elected officials objected that money from a National Endowment for the Arts grant went to Queer artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Karen Finley. Culture wars broke out as the conservative right attempted to eliminate funding of controversial art. US law prevented any federal money being used to "promote, encourage or condone homosexual activities," which also led to the defunding of AIDS programs. In 1987, the central government in the UK banned local councils from using public funds to "promote homosexuality" or a "pretended family relationship."

Queer theorist Paula Tredichler said the 1980s saw two epidemics of significance: "One epidemic was called AIDS, and it raised the stakes of homosexual visibility to a matter of life and death. The other was the word 'queer.' It spread from closets to the streets, from sensationalized exposes to countercultural magazines, from bars to zines, from alternative galleries and to the occasional museum. Naturally, the concept insinuated itself into the academy."

The term "queer" was re-appropriated as a matter of pride. Its spirit of social deviance and lack of clear definition enabled it to be used as an umbrella term, including all the groups referred to under the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, and intersex umbrella. As Alex Pilcher says: "The label has a history of being spoken in hatred - many of us remember being on the receiving end of it as a term of abuse - but from the mid 1980s onwards there has been a defiant move to reclaim the word."

Identity Politics

As right wing, conservative and religious groups tried to suppress the queer voice in public, a new anti-authoritarian political and cultural wave began. Identity Politics refers to the formation of social groups in which people of specific backgrounds united to fight for their specific interests and common causes without regard to wider political organizations. In gay communities, this meant people were encouraged to come out to their friends and families and make their voices heard by taking part in protests, marches, and direct action. The accompanying art was loud, confrontational and asked questions about what art should be and who should make it. Activist group the Gay Liberation Front proposed gay identity as a revolutionary form of social and sexual life that would reinvent traditional systems of sex and gender. More recently, however critics have questioned the validity of Identity Politics that casts the self or group as an identity defined by its opposition to an "other."

Feminism

Queer Art has had an important role in subverting repressive gender norms. The work of Claude Cahun, Gluck, and Catherine Opie can be seen to operate within a strongly feminist framework, as the artists seek to dismantle patriarchal notions of femininity. Judith Butler, leading feminist theorist, wrote, "A feminist view argues that gender should be overthrown, eliminated or rendered fatally ambitious precisely because it is always a sign of subordination for women." Queer Art then can be seen to dance along a parallel line as it works to dismantle oppressive patriarchal norms. The feminist movement also provided practical support to the Queer movement in the form of health activism, as the AIDS crisis saw important information about the disease and its transmission withheld from gay communities. As critic Catherine Lord says, "Much of the historical research, cultural analysis and legal defense that laid the groundwork for a sex-positive queer culture during the AIDS crisis was instigated by the queer leather community and pro-porn lesbians and feminists."

Queer Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Painting

The raw expression invited by the medium of painting has allowed portraiture to become a space for the queer artist to explore notions of love and sexuality. From the covertly sexual works of John Singer Sargent to the more open and defiant male nudes of Larry Rivers, painting has provided a venue for the sensual element of the queer experience to be explored.

British painter David Hockney's images of men in showers and swimming pools show the celebration of gay love on canvas. Art historian Richard Meyer writes, "In responding to the academic requirement for life painting, Hockney insists on the importance of the artist's desire for the naked body he depicts. Far from a dispassionate study of the human figure as an ensemble of volumetric forms (it's only a sphere, a cylinder, a cone), Hockney proposes a necessary link between artistic achievement and sexual attraction."

Murals, Graffiti, and the Public Space

Sculpture provided a way for the queer experience to be literally brought out of the closet and into the street, as in the work of George Segal's Gay Liberation, which was installed across the street from the old Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. The AIDS Memorial Quilt is a still-growing piece of public art where people can commemorate via quilt squares loved ones lost to the disease. The Names Project, as it became known, was conceived by gay rights activist Cleve Jones in San Francisco. When it was first displayed for the first time on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., during the 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, it covered a space larger than a football field. Today, more than 48,000 people have added panels honoring the names of their lost friends, and it has germinated into different incarnations around the world, won a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, and raised $3 million for AIDS service organizations.

In the face of centuries of repression, the public space became an important new venue for gay artists to display their work. Jenny Holzer would hang her photocopied Truism posters around New York in the late 1970s. A few years later Keith Haring would use advertising panels for his street art, and David Wojnarowicz spray-painted graffiti on the Chelsea piers in the early eighties. Artists proclaimed they would no longer be closeted, and the progressive city of New York provided the perfect gallery.

Activist artists aim to create art that is a form of political or social currency, actively addressing cultural power structures rather than representing them or simply describing them. By taking on the conservative right in the Culture Wars, queer artists had no choice but to become activists as they fought for knowledge, fairness, and representation. Feminist graffiti from the 1970s, as shown in Jill Posener's photographs, proved a vital influence for gay activism.

In London, Posener produced images of "refacings" of the spaces of public advertising that would go on to influence Queer Art. One advert, claiming, "We can improve your nightlife," had the witty missive spray-painted beneath: "Join Lesbians United." A Fiat ad claimed, "If this were a lady it would get its bottom pinched," to which Posener added, "If this woman were a car, she'd run you down."

Critic Catherine Lord explained, "With their cheap, sly, hit-and-run tactics, such activists refused the mass-media definition of 'success,' working their alterations on a precise and local level. The interventions nudged cultural politics out of the realm of...positive imaging of identity and turned subcultural representation into a matter of scanning between the lines and reading the writing on the wall."

And San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City have become huge urban canvases for self-labeled "queer street artists" like Jeremy Novy, Homo Riot, and Jilly Ballistic to fight homophobia by claiming a share of ownership in public space.

Photography

Photography has provided a fertile ground to subvert "normalized" notions of love and sexuality and to bring what has traditionally been considered "deviant" into the light, thus bestowing it new agency. Whether they are Annie Leibovitz's images of the dying Susan Sontag, or Catherine Opie's images of gay and lesbian domesticity, photography has proven a powerful medium to explore the queer experience. But it also found real power in subverting images from the AIDS crisis, during which the right-wing press would revel in publishing pictures of emaciated victims to point the blame at those it said were responsible for spreading the disease. Queer artists and photographers would reel against this, presenting their subjects in colorful, celebratory and defiant lights.

Other Visual Art

Other artists took on conventions and laws that prevented them from exhibiting more overt or graphic scenes in a public space by creating more subtle, coded works. Visual artist Félix González-Torres insisted on his right to place explicit sexual figuration in the public sphere. In his 1991 work Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA), the artist poured an enormous pile of brightly colored candies into a corner and invited viewers to take pieces of the candy. The pile of candy weighed exactly 175 pounds - the "ideal" weight of his lover. Those that ate the sweets had been seduced into swallowing queer intimacy. It becomes a work of performance art, where the viewer unwittingly becomes the actor.

Later Developments - After Queer Art

In a 1991 essay, Judith Butler argued that homosexual identity can never become a stable entity. She wrote, "Conventionally, one comes out of the closet [...] so we are out of the closet, but into what? What new unbounded spatiality?...Curiously, it is the figure of the closet that produces this expectation, and which guarantees its dissatisfaction. For being 'out' always depends to some extent on being 'in;' it gains its meaning only within that polarity." Contemporary artists such as Keltie Ferris interrogate this identity that can only be measured against something it is not. In Gaydar (2014), Ferris offers no visual clues as to her sexuality, but the title acts as a rejoinder to society's fascination with her identity.

A queer reading of the work is made difficult in the light of recent approaches to criticism which have tried to divorce art from the personality of the artist. As Alex Pilcher explains, "The meanings of an artwork are no longer credited exclusively to the artist's intentions; the active role of the spectator and the context of viewing are now accorded more clout....When even erotic, figurative art is hard to characterize as queer without falling back on biographical data, abstraction tests queer art history to the limit."

The redefinition of the word "queer" has now reached a turning point, argue Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord. With its new-found acceptance, it now runs the risk of being recuperated as "little more than a lifestyle brand or niche market" - what was once deviant is now mainstream, thus destabilizing its future.

Useful Resources on Queer Art

- Art and HomosexualityOur PickBy Christopher Reed / May 2011

- A Hidden Love: Art and HomosexualityBy Dominique Fernandez / June 1, 2002

- Art and Queer CultureOur PickBy Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer / April 2, 2013

- A queer little history of artOur PickBy Alex Pilcher / October 10, 2017

- Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American PortraitureBy Jonathan D. Katz and David Ward / November 2010

- Queer British Art 1861 - 1967Our PickEdited by Clare Barlow / October 10, 2017