Summary of Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks was part of the first generation of revolutionary and openly bohemian female artists. As a practicing artist pre-first World War, this was a moment in history when women did not have the right to vote and as such did not have the due respect or the same opportunities as men. The way to succeed at the time, or perhaps simply to be noticed was to mimic masculine appearance and to renounce femininity for all of its restriction and expectation. Thus many of Brook's notable paintings depict androgynous figures, out in the world infused with heroism and purpose rather than bound and hidden by domesticity. In this respect Brooks' struggle to be free has much in common with her English contemporary, the writer, Virginia Woolf. Both women resolutely fought for independence in mind and finance, and understood that their dedicated artistic pursuit came at great price; Woolf famously committed suicide and although Brooks lived to the glorious age of 96, she tragically titled her lifetime memoirs No Pleasant Memories.

Accomplishments

- Brooks established a signature palette of soft and subdue grey. Her work is thus similar in tone and comparable to that of her fellow American (and fellow émigré to Europe), James McNeill Whistler. On the one hand, the absence of color in Brooks' paintings could stand as a mark of melancholy; the shadow that she says had been cast over her life since childhood. However another plausible influence is the invention and subsequent increase in use of photography; at this point photography was executed only in black and white and variant hews of grey, and like the pictures of Brooks, the new medium sought to successfully illuminate the spirit of the sitter.

- Brooks contributed to many significant art movements and trends in thinking at the time. Her intense interest in portraiture supported the emerging study of psychoanalysis, a practice whereby individual identity for the first time was scrutinized. In the same tone, Surrealism sought to expose and illustrate unconscious fear in a way that Brooks pre-figures in her drawings on paper. Furthermore, as Brooks places great importance on the depiction of restrained beauty, and like William Morris extends her art to an interest in interior design, she is also a key figure working in the realms of Aestheticism and Arts and Crafts. Her relationship with this movement is not clear-cut however, for although attracted by the sensual, Brooks subtlety infuses beautiful pictures with social and political content.

- Like fellow artists, Rosa Bonheur and Claude Cahun, Brooks lived the majority of her adult life entwined in romantic relationships with other women. As such she has become a pioneer and icon for same sex relationships. Since feminist scholarship has become more widespread the oeuvre of Brooks had been re-visited, re-invigorated, and better understood. She is now quite rightly credited as a leading figure and shining light guiding a major shift towards gender and sexual equality in the twentieth century.

Important Art by Romaine Brooks

Azalées Blanches (White Azaleas)

Painted primarily in a palette of muted brown, grey, and cream, Brooks' painting features a slight nude young woman reclining on a large sofa. Reviews of the work written at the time compared the work to Francisco de Goya's La maja desnuda and Édouard Manet's Olympia, but whilst the sitters in these paintings look directly at the viewer, the woman here gazes out into the distance. The crucial difference is that this woman is seen and painted by another woman, not by a man. As such the woman does not appear sexually available in the same way (even though Brooks may indeed be physically attracted to her). She is lost in thought and dream. As the little ship paintings above her seem to suggest, she imagines that which is elsewhere, far away, and waiting to be found on the horizon.

This painting is a strong example of Brooks' early work. While she often focused on women as her main subjects, at the beginning of her career depictions lacked the intimate qualities embedded in her later portraits, which were almost always of lovers and friends. This painting is a somewhat less personal representation of a nude model. Simply by being a woman painting a nude woman was a rare occurrence however, and such reveals the artist's modern forward thinking whilst furthermore achieving an exhilarating sense of breaking taboos. According to writer, Joe Lucchesi, "the subject was highly unusual for a female artist, and the particular erotic charge of White Azaleas was virtually unknown in the work of contemporary female artists." That the artist was aware of the provocative nature of such a subject and her desire to push boundaries within the art world was asserted when she stated, "I grasped every occasion no matter how small to assert my independence of views. I refused to accept slavish traditions in art, and though aware it would shock, I insisted on marking the sex-triangles of all my female nude figures...."

The painting also importantly highlights Brooks' early association with the Symbolism art movement and especially the influence of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Historian Whitney Chadwick describes how in this painting the woman becomes a key item, "...in carefully arranged still-lives that evoke the melancholy and morbid eroticism of the symbolist poets. As in Whistler's Nocturnes, 1870s, feelings are evoked rather than declared. Mood emerges from subtle modulations of a palette mostly limited to ochre, gray, umber, and black, relieved only by the splashes of white produced by a floral arrangement...."

Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

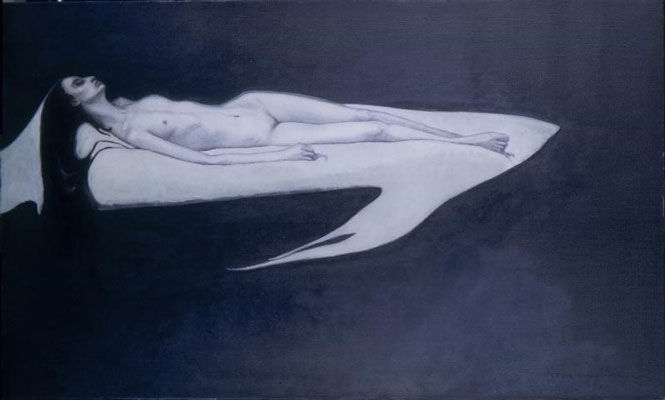

Le trajet (The Crossing)

A nude woman, lying on her back, arms and legs relaxed and outstretched at her sides, with long black hair flowing behind her, appears to float in a dark void across the top half of The Crossing. It is as though the figure rests on a wing or upon a delicate cloud and it remains ambiguous if she is living, or has died. Is she "crossing" to the afterlife? There is a strong sense of expressionist drama at play here and the paintings of Edvard Munch at once comes to mind as well as the metaphysical imagination of the artist and poet, William Blake.

The model is Brooks' lover at the time, Ida Rubenstein, a beautiful dancer. The lack of a domestic setting for the nude and the dreamlike way she seems to drift across the canvas forces the viewer to directly and unapologetically confront both female sexuality generally and more personally the lesbian love that the artist had for the subject. As Joe Lucchesi explains, "...Brooks sharpens, intensifies, and consolidates the symbolist iconography of female sexuality."

Of interesting note however, when Brooks exhibited this painting she referred to it not by its title but as "The Dead Woman." In so doing, she seems to qualify the first intuitive interpretation of the work, that the woman has died and that in turn the artist prevents the viewer from being able to engage with the body sexually. Brooks is asserting her privileged relationship with Rubenstein (a sexy Parisian dancer who would usually perform and reveal only what she wanted) as something that is denied to others, something that is different and that nobody else can see. For Lucchesi, this painting "...alludes to the point at which identity gives fully over to the invisible, in the passage from life to death. This tension suggests that even as the physical body of Rubinstein becomes completely available to vision, the interior identity it contains will never be recovered or revealed." Brooks once again successfully asserts that a woman is more than her sexuality and that depth (even if she must be dead for others to finally see) always prevails.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian Museum of Art, Washington DC

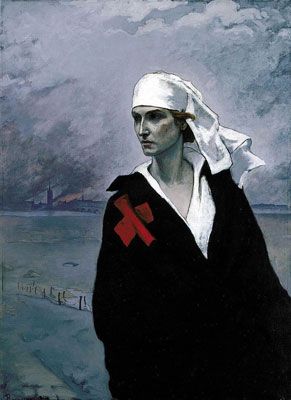

La France croisée (The Cross of France)

A large and powerful female figure dominates Brooks' La France croisée. The woman, who we assume is a nurse for wounded soldiers, wears a cape like black jacket sewn with the symbol of the Red Cross on her right shoulder; her head is wrapped with a long, white flag-like head scarf that seems to call for surrender (and also echoes the dressings that she may have applied to injured men). She stands in front of a depiction of the city of Ypres, wrought by devastation as buildings burn in flames in the background, and as such, hopes for peace. The woman is depicted as a towering hero, with a determined stare and the innocence of intent. She recalls Eugéne Delacroix's famous depiction of Liberty Leading the People (1830); it is as though this woman is the figure who holds the capacity to lead people towards a better future, if they have the courage to join her.

The painting acts as a rare example of Brooks using her art to make a political statement. She pays homage to all the people who tried their hardest to help during World War I. The figure stands stoic and resolved to persevere over the violence that is happening all around her. Cassandra Langer describes this work as, "...Brooks' message of nonviolent resistance and restoration of civility, which translated into hope of triumph for the entrenched French." Interestingly, she chose her lover at the time, Ida Rubinstein to be the personification of the female hero, brings a personal aspect to this painting and pays tribute to the hard work they both did during the war. Brooks' was as an ambulance driver.

The painting was displayed in a Paris gallery in 1915. Brooks created an accompanying flyer that featured a reproduction of the painting alongside a poem by Gabriele D'Annunzio and then sold this to patrons. The funds raised from the thoughtful pamphlet sales went directly towards helping the Red Cross and other war efforts. Such actions, her work as a wartime ambulance driver, and the creation of this painting all contributed to Brooks receiving the Cross of the Legion of Honor by the French government in 1920.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

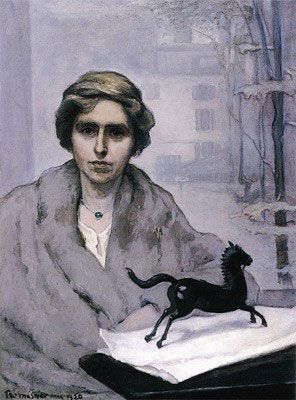

Miss Natalie Barney "L'Amazone"

This painting depicts Natalie Barney, a talented writer, and the woman with whom Brooks remained romantically entwined for 50 years. The portrait is somewhat softer and less formal than previous works and as such suggests the comfort and love that Brooks found in the company of Barney. Barney sits - with a snowy scene painted as a backdrop out of the window - inside of her apartment keeping warm wearing a lavish grey coat. The house is 20 Rue Jacob where Barney lived when Brooks met her. Brooks immediately shows her deep admiration for Barney through the inclusion of a small sculpture of a horse. This not only alluded to the sitter's love of riding that led Remy de Gourmont to nickname her "the Amazon", but also the general wildness and free spirited nature of her character.

In Greek mythology the Amazons were a tribe of women warriors, aggressive and powerful. Furthermore, the significance and symbolism of the horse is important here as it is a motif that recurs again and again in Brooks' work. The horse represents an untamable force of nature but also stands as a creature that is extremely kind and useful to the needs and progress of people. As such artists throughout history return to equestrian images. For example, Odilon Redon, French symbolist often depicted horses and so did the Blue Rider group surrounding the Russian painter, Wasilly Kandinsky. Also of course, there is the long history of great men seated on horseback as means to assert their power.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

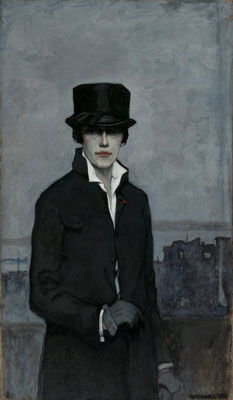

Self-Portrait

Here the artist stands tall, assured, and beautiful, dressed in a black equestrian suit with dark grey gloves and complete with top hat. She stands in front of a landscape of decaying buildings, but by contrast, she herself is at the pinnacle of her creative career making what was to become her seminal work. Rendered, as is typical, in a somber palette of gray, black, and white, the only bit of color is the tiny red Legion of Honor cross, pinned on her jacket, which she wears with great pride and honor. Indeed, similar to a J.M.W.Turner landscape, Brooks presents the viewer with muted tones but then grabs the eye's attention with highlights in red. It is not only the cross, but also the rouge on the woman's lips that draws in the gaze. These hints of color could be described what years later, when discussing photography, were called "punctum" by the scholar, Roland Barthes; such are the moments, the glimmers of meaning that hit hard and stay with us long after seeing an image. As such, we remember pain, sexuality, and honor because of the small but memorable traces of red in this painting.

By depicting herself in non- gender-specific costume, Brooks is making the statement of her career. She shuns the shackles of femininity and instead mimics masculine dress in order to progress with work, ideas, and artistic idealism. The equestrian costume was a good option to achieve this intended effect and as Whitney Chadwick explained, by the 1800s, "[t]he adoption of equestrian attire signals a loosening of the figure's ties to the conventionally 'feminine' and, at times [...] specifically points to sexual ambiguity." More than simply an embrace of modernism where the boundaries between gender lines was beginning to become blurred in general, these works also specifically assert the status of lesbians within society. For Chadwick this is "...a new image of the noble and independent lesbian." As such the painting revels Brooks as a revolutionary, making visible an aspect of identity that previously had been entirely hidden.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Caught

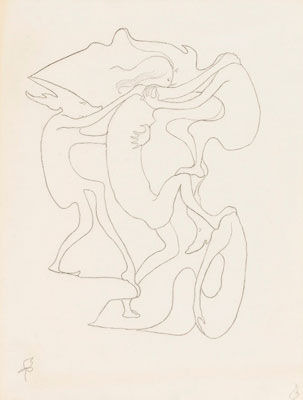

Caught is a work on paper by Brooks that is part of a larger series. The work features a central female figure who appears to be being restrained by three demon-like creatures. This is one of many drawings that Brooks created in the early 1930s, which were intended to be included in what remained her unpublished memoir, No Pleasant Memories.

The demons here could be representations of the tormentors of the artist's early childhood - for example, her mentally ill and abusive mother of whom she stated, "I...cannot remember a single jot of kindness on her part;" and an insane brother who according to some historical accounts may have molested Brooks. The more passive demon could be a reference to her older sister Maya who remained uninvolved with her sister and of no help to her during their formative years. Or, with no shortage of traumatic episodes, the demons could stand for Maya's husband, the man who forcefully raped and impregnated Brooks.

These drawings, often completed in what appears to be one single, continuous line have contributed to comments that Brooks' was a forerunner to the movement of Surrealism. The artist Édouard Georges Mac-Avoy went so far as to call her "the first surrealist." These drawings do indeed have much in common with the early automatist works of André Masson. This line of enquiry is made stronger by the subconscious, dream (and nightmare)-like themes of many of the drawings. According to historian Cassandra Langer, "Romaine Brooks was well known for describing her drawings as spontaneous creations of the imagination" and as such, "...her depiction of overweight, suffocating monsters in drawings[...] have always been interpreted as proto-Surrealist fantasies."

Graphite on paper - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

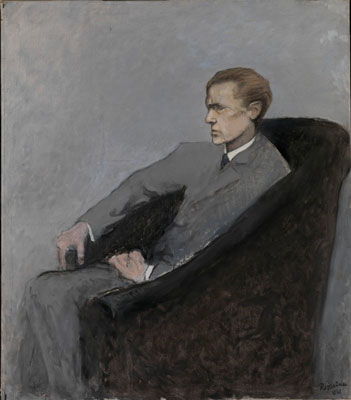

La Duc Uberto Strozzi (Duke Uberto Strozzi)

A rather formal and somber portrait, in this relatively late painting for Brooks she depicts a man seated in a dark wrap-around armchair looking thoughtfully outwards. The gray of the man's suit at once compliments and merges with the lighter gray background. The work is considered to be the last major work completed by Brooks before her death nine years later. As such the sitter was considered an important figure in her life. She had first met Duke Uberto Strozzi during the war and described him as "blond and slim almost to emaciation. His gray eyes are deeply set and his face though sharp and youthful seems as though incised on a very old medal. The first time I met this young man he suggested something medieval and ascetic, an impression I could never evoke again." Somehow the man's appearance brought feelings of nostalgia to Brooks and unearthed something of a lost golden age of art history.

Furthermore, the painting is one of the rare instances when Brooks' chose a man as her subject. She portrays him with the same sensitivity as her female sitters and similarly imbues him with great depth and capacity for reflection. Indeed, perhaps by age eighty-seven, somehow the battles of gender and sexual equality were no longer hers to fight and she was able to see all people for their qualities. Whitney Chadwick supports this idea when she states, "Brooks' portrait of the duke is a sympathetic if austere portrayal of a man, withdrawn into his own soul, who clearly stands for the aristocratic ideal that Brooks had pursued through her life. Like her earlier portraits, it is an unflinching image of the individual alone, caught between introspection and a defiant assertion of self against an inhospitable world."

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Biography of Romaine Brooks

Childhood and Education

Romaine Brooks was born Beatrice Romaine Goddard to an affluent American family whose wealth was derived from her mother, Ella Waterman's family mining fortune. Sadly, this financial security did nothing to prevent a miserable childhood. The youngest of three children, Brooks' father left shortly after she was born and her mother focused all her love and attention on the artist's brother, St. Mar. Mental illness was prevalent in the family and greatly affected her mother and her brother, both of whom were tormented by imaginary voices. When her cousin committed suicide, her mother told her young daughter that she had seen the cousin's ghost. This traumatized Brooks to the extent that she started to create disturbing drawings that featured spirits. Of her childhood, she stated, "My earliest recollection...is an immense impression of fear."

At age six, Brook's mother also abandoned her; she left for Europe with only her son and entrusted Brooks to the care of a poor laundry woman living in New York City. Despite living in squalor, Brooks benefitted from this experience; the family was warm and loving, and the woman of the house encouraged Brooks to draw, something her mother had forbidden her to do. Noticing talent, her surrogate mother-figure also introduced the young Brooks to an artist living in a nearby tenement who further nurtured the young girl's growing interest in art. Eventually her wealthy grandfather located Brooks and sent her to a boarding school. Here she was taught art however many of her fellow students and teachers found her drawings of monsters and ghosts unsettling. Her education continued at an Italian convent, to where her mother sent her to from age 14. Very unhappy at the convent, she attempted suicide and was expelled after a bout of pneumonia. Later at age seventeen, she was sent by her mother to a finishing school in Switzerland where she excelled in art and music. At age 19, she then moved to Paris.

Early Training

In 1895, at age 21, Brooks attempted to break all financial ties with her mother. Unfortunately a highly traumatic episode ensued; without funds she struggled to get by modeling for artists and singing in cabaret, but she was soon forced to ask her older sister Maya for an allowance. When Maya's husband, Dr. Alexander Hamilton Phillips visited Brooks to deliver the money, he raped her resulting in a pregnancy. Brooks gave birth to a daughter in 1897 and immediately gave the baby to the care of a convent. Tragically the baby died less than three months after being given away, news that Brooks only learned of five years later when she returned to the convent in the hope of reuniting with her child.

She had left her baby in order to travel to Rome and begin formal art training; she was 24 and started to attend the Scuola Nazionale. As the only female student enrolled however, she had a difficult time and experienced sexual harassment from her male classmates. According to her biographer, Cassandra Langer, one particular instance involved a male student leaving cards on her classroom stool with inappropriate images on them. The situation escalated and she then found an open book on her stool with provocative text underlined; Brooks was outraged so took the book and hit the instigator hard in the face with it, finally putting a stop to the harassment. After concluding her studies in Italy, in 1900 she continued her artistic education taking classes at the Académie Colarossi in Paris, France.

Brook's brother died in 1901 and then her mother passed away in grief and plagued by diabetes less than one year later. Brooks was thus transformed from a struggling artist into an heiress and an independently wealthy woman. The newly inherited fortune allowed her to spend the rest of her life financially unencumbered. Of this change in her circumstances she stated, "I knew somehow that the simple, almost monastic, life so congenial to me, was now over." With no interest in a traditional lifestyle, in 1903 Brooks entered into a marriage of convenience with John Ellingham Brooks. For the artist, a lesbian, it meant, in addition to a new name, that her husband could serve as a buffer against interest and interference from other men. In turn, Brooks gained the freedom necessary to pursue her art, and her homosexual husband was assured financial security for the rest of his life. Brooks quickly separated from her husband due to his increasing demands that she act more traditionally and attempts to control her money, but the two remained legally married until John Brook's death in 1929, an arrangement that had worked well for both of them.

Mature Period

Brooks spent the next decades traveling and living in Europe and establishing her reputation as a serious artist. She spent time living in London and on the Cornish coast, in St. Ives. She started to focus entirely on painting portraits, which she now rendered in a very subtle color palette, basically consisting of a vast spectrum and range of gray. It was at this time that Brooks also became interested in interior design, often using this same reduced and muted color palette to decorate the apartments of her Parisian friends as well as her own. Residing in England during this period, Brooks is likely to have encountered the work of William Morris and other artists involved in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Throughout her burgeoning career Brooks engaged in intense romantic relationships with controversial figures that would also serve as the subjects for her portraits, a dimension that added great intimacy to her work. Such relationships included a famous dominatrix, Winnaretta Singer, the dancer Ida Rubinstein (said to be the Lady Gaga of her day), and even a rare heterosexual affair with an Italian poet called Gabriele D'Annunzio. D'Annunzio's association with the development of Fascism in Italy, as well as Brook's later support of the plight of Italians during World War II tainted her reputation thereafter.

The artist's longest relationship by far, lasting for more than five decades, was with the fellow American heiress and writer, Natalie Barney. Barney was also in love with Duchess Lily de Gramont, which resulted in a unique open domestic arrangement whereby the three women lived together as a romantic trio until Gramont's death in 1954.

In addition to her chaotic upbringing, heavy with abandonment, madness, and loss, Brooks' life was also shaped by living through the turmoil of two World Wars. During World War I she a volunteered as an ambulance driver and created a fund to support injured French artists, feats which later earned her the French Cross of the Legion of Honor. During World War II, Brooks was trapped in Florence with Barney, constantly trying to protect her lover (because of her Jewish heritage) from the Nazis. The couple lived in harsh conditions, even having to endure the forced stationing of German soldiers in Brooks' home.

Late Period

Brooks' artistic output slowed down greatly after the end of the Second World War. While Barney returned immediately to Paris, Brooks remained for many years in Italy. Of this period she stated, "I remain alone seeking to find the other, the artist self that has deserted me during these years of the war on the hills of Florence." Somehow recognizing that her artistic output was dwindling, Brooks became overcome with a strong desire to look to her legacy and as such approached the Smithsonian Museum of Art in Washington, DC to take much of her work, an invitation that the gallery accepted in 1967.

In the remaining years of her life Brooks' health failed and she grew increasingly depressed and paranoid. Of her last years she wrote, "The death of my mother and brother had not liberated me mentally, and I felt that some part of me still remained with them." Easily agitated by and unnerved by sudden noise, the artist preferred to stay quiet and alone in darkened rooms during the last few years of her life. At the grand old age of 96, Brooks abruptly ended her relationship with Barney, and the same year died alone in her French home.

The Legacy of Romaine Brooks

The style of Romaine Brooks' art in many ways defies classification and does not easily fit into one stylistic category. However, she has been most frequently linked to the movements of Aestheticism and Symbolism because of her leaning towards the non-narrative and the romantic and lyrical qualities of her portraits. While Brooks did not embrace the vivid colors of many of her fellow modernists, she nevertheless made the same bold and somewhat simplified expressive gestural lines as her contemporary Fauves and Cubists. Her portraits are unapologetically honest and real in the same way that the likes of much later twentieth century portraitists, including Alice Neel and Lucian Freud took on board.

The intense concentration on portraiture and investigation into the notion of selfhood is something that Brooks shared with other women painters at the time, and similarly has inspired future generation of women painters. The English woman Gwen John and also the Finnish artist, Helen Schjerbeck repeatedly depicted their own image. John conveyed frustrations surrounding her own visibility by often including a soft blur, and Schjerbeck's face becomes increasingly reductive and skeletal as the years pass by. It comes as no coincidence that this intensified focus on identity comes at the same time as the onset of psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud started his clinic in 1910 and had already published many notable works by this point; portrait artists working at the turn of the Twentieth Century exemplify this new human exploration.

In her repetition of the motif of women wearing masculine attrite in order to be taken seriously as artists, her work looks forward to the exhilarating career of Frida Kahlo. As such, her legacy lays crucial foundations for the development of Feminist art making and a woman's general refusal to follow convention and succumb to repression. Furthermore, and bringing her influence closer to the present day, Brooks' depiction of women in male dress, helped to push the boundaries surrounding the politics of gender identity and in turn to elevate the subject of the lesbian woman in fine art. As such Brooks' cleared important pathways for contemporary artists interested in the exploration of sexual identity, including Catherine Opie and Gillian Wearing.

Influences and Connections

-

![Aubrey Beardsley]() Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley -

![Jean Cocteau]() Jean Cocteau

Jean Cocteau -

![Man Ray]() Man Ray

Man Ray -

![James Whistler]() James Whistler

James Whistler - Édouard Georges Mac-Avoy

- Natalie Barney

- Gabriele D'Annunzio

- Charles Freer

- Élisabeth de Gramont

- Robert de Montesquiou

-

![Jean Cocteau]() Jean Cocteau

Jean Cocteau -

![Man Ray]() Man Ray

Man Ray - Édouard Georges Mac-Avoy

- Gabriele D'Annunzio

- Natalie Barney

- Charles Freer

- Élisabeth de Gramont

- Robert de Montesquiou

- Ida Rubenstein

Useful Resources on Romaine Brooks

- Between Me and Life: A Biography of Romaine BrooksBy Meryle Secrest

- Romaine Brooks: A LifeOur PickBy Cassandra Langer