Summary of Alice Neel

Alice Neel, an unshakable original, witnessed a parade of avant-garde movements from Abstract Expressionism to Conceptual Art, and refused to follow any of them. Instead, she developed a unique, expressive style of portrait painting that captured the psychology of individuals living in New York, from friends and neighbors in Spanish Harlem to celebrities. Part of what makes Neel one of the greatest American portraitists of the 20th century is her refusal of traditional categories (gender, age race, social status, etc.). She does not presume what she does not know. She observes each subject with a fresh eye. Neel's insights into the human condition never wavered, remaining direct, unflinching, and always empathetic.

Accomplishments

- Types are less interesting to Neel than individuals. Andy Warhol and her neighbor's children are subjected to the same level of scrutiny, curiosity, and psychic assessment. "If I hadn't been an artist, I could have been a psychiatrist" she once said.

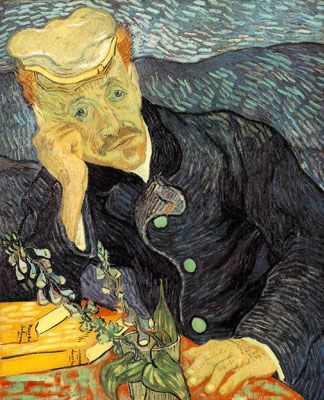

- At a time when it was deeply unfashionable, Neel persisted in being a figure painter and a portraitist. While fully engrossed in the New York art scene and connected with its major innovators, she remained steadfast in her choice of style and subject matter, unswayed by an art world that favored abstraction. She persisting in making work that pleased her, regardless of what anyone thought. In this respect, she is very much like another great portraitist: Vincent van Gogh.

- Neel was virtually unknown and had only a handful of solo shows prior to 1970. In the last two decades of her life, she had sixty. This was not purely due to the strength of her work, but to a seismic shift in the art world, which had begun to acknowledge the achievements of minorities and women.

- While prolific, Neel appears to have been relatively uninterested in self-marketing. In this respect, she is different from many other successful artists of her generation, particularly women, who had to work especially hard to get noticed by the critics. Louise Nevelson, around the same age, is an especially intriguing study in contrast.

Important Art by Alice Neel

Carlos Enríquez

This early work depicts Neel's husband, the painter Carlos Enríquez, a year after they were married. The portrait displays many of the stylistic and compositional features evident in her mature work. It is clear, however, that Neel was still evolving as an artist. The face, with its distracted features, looks past the edge of the frame, as if focused on a faraway thought. The background here is much darker and the features more idealized than in Neel's later portraits (although, after all, this was her lover). Interest in psychological depth, while evident here, would be fully mastered in her later work.

The pair met in 1924 during a summer painting course in Pennsylvania. He was expelled due to lack of participation; Neel left the program with him. Enríquez returned to Havana in the fall, but the couple carried on their romance through letters. His wealthy family disapproved of Neel and his desire to be an artist (one can only imagine what they thought of her professional ambitions).

Oil on Canvas - Private Collection

Pat Whalen

Neel's passionate interest in left-wing politics is evident in her portrayal of Communist activist and union organizer Pat Whalen, whom she painted when she was involved with the WPA, part of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. Here, Whalen is portrayed as the archetypal blue-collar worker. He looks up from a copy of the Daily Worker (the official newspaper of the US communist party), his fists clenched in an expression of resolve and determination. Hallmarks of the artist's personal style are abundantly evident here: the use of flat, unmixed color, the expressive brushstroke, and particular care with the features of the sitter's face and hands that convey a deeper psychology. Neel once observed, "people are the greatest and profoundest key to an era." Here, honing in on a single subject, she articulates the intensity of a struggle that affected millions of Americans in the 1930s and beyond: the struggle for worker's rights.

Oil, Ink, and Newspaper on Canvas - Whitney Museum of American Art

Puerto Rican Boys on 108th Street

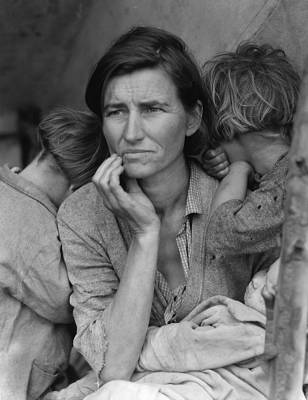

Neel moved from Greenwich Village to Spanish Harlem in 1938. The Village, she felt, was too full of pretentious bohemians. She moved in with the Puerto Rican musician Jose Santiago and began to paint many portraits of friends and neighbors. The two boys here are not like the cherubic innocents seen in many traditional portraits of children. They are nattily dressed like men, not boys, and come across as tough and streetwise. While they are Hispanic, Neel neither plays down nor stereotypes this element. Unlike many of Neel's other portraits, in which backgrounds are typically minimal, the details of the urban landscape are clearly rendered here. Neighborhood residents linger and chat on a stoop, advertising posters peel off the wall of a corner shop, and a green graffiti tag reading 'Felipe' is clearly visible. In this respect, many of her paintings from Spanish Harlem recall the aesthetics of American documentary photographers such as Berenice Abbott and Dorothea Lange. While many portraits (including Neel's) have a universal or timeless quality to them, these two boys are distinctly of a specific time and place.

Oil on Canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Hartley

Some of Neel's most impactful paintings focus on the people closest to her. This portrait of her son, Hartley, is one of the most famous. Though there is strength and confidence in his pose, with arms and legs akimbo, there is also vulnerability, as well as a weary hardness in Hartley's features. He seems to be preoccupied, or lost in thought, as evidenced by the fact that his gaze avoids that of the viewer. As in many of her portraits, the periphery of the frame is unfinished. This focuses our attention on the central details of the image, for example, the rendering of the shadows on his shirt and pants, which lend them an almost photorealistic quality, and the bold, dark outlines of the body and face. Hartley was Neel's son with the documentary filmmaker Sam Brody, a difficult and sometimes physically abusive man. Struggling to support her family, Neel depended on welfare - and even shoplifted occasionally - to make ends meet. A firsthand knowledge of hard times radiates through Hartley's stern expression, but the restless energy in his lanky form suggests possibility, as opposed to resignation. Neel's expert brushwork, here at its best, lends an immediacy to the figure that makes it look as if it might get up and walk. Hartley's son, Andrew, went on to produce a documentary film about his grandmother in 2007.

Oil on Canvas - National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.)

Andy Warhol

One of Neel's best-known works, this portrait of the legendary figure contrasts dramatically with the glamorous image Warhol cultivated for himself. His eyes are closed, suggesting sadness, and discomfort with being looked at (Warhol was famously sensitive about his looks). Without the spiky white wig, sunglasses, and black turtleneck shirt, and without the admirers, celebrities, and hangers-on, he appears vulnerable and old. In 1968, two years before the famous Pop icon sat for this painting, he was shot three times (with a gun) by Valerie Solanus after refusing to produce her play. Alone and shirtless, against a spare background that emphasizes his isolation, Warhol's pink flesh contrasts with the green shadows on his face and body. Large scars across his torso, with the corset he wore to support his damaged abdominal muscles clearly visible, reveal the enduring evidence of that attempt on his life. Here, Warhol's public persona as an immortal icon of cool falls away and he is revealed as a fragile human being. Evidence of Neel's mastery as a portraitist, the work rejects the superficial ways in which we perform identity and assess power, and suggests an alternate model for gaging the human condition: empathy.

Oil and Acrylic on Linen - Whitney Museum of American Art

Self Portrait

Neel was one of the first (if not the first) octogenarian woman to exhibit a portrait of herself as a nude. Neel began the self-portrait in her mid-seventies, abandoned it, and returned to it five years later when she was invited to take part in an exhibition of self-portraits at the Harold Reed Gallery in New York in 1980. It depicts Neel in the nude, sitting on a striped chair in her studio. The details of the floor and walls give way to negative space after forming a kind of halo around her. White hair, wrinkles, and sagging stomach (signs aging women are taught to conceal or hide) appear matter-of-factly at the center of the work. She is the clear focus of the painting. She wears only her glasses, and holds a paintbrush in one hand and a cloth in the other. Her steady gaze meets ours, and suggests self-acceptance, even confidence. While of course the female nude is one of the most popular subjects in art, scenes of older nude women as anything but the subject of ridicule are exceedingly rare. In this path-breaking self-portrait, Neel breaks a cardinal rule in Western art, wearing the evidence of her eighty years without shame and as a truly radical artist, at the very top of her game.

Oil on Canvas - David Zwirner Gallery (New York)

Biography of Alice Neel

Childhood

Alice Hartley Neel was born into a colorful American family. Her father, George Washington Neel, was an accountant with the Pennsylvania Railroad, and hailed from a clan of steamship owners and opera singers. Her mother, Alice Concross Hartley, was a descendant of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. Young Alice was the fourth of five children, with three brothers and a sister. Her oldest brother, Hartley, died of diphtheria shortly after she was born. He was only eight years old. Several months later, Neel's family moved to the small town of Colwyn, a short distance from Philadelphia, where she attended primary school and high school.

After graduating from high school in 1918, Neel took the Civil Service exam and accepted a secretarial job with the Army to help support her family. She worked there for three years while pursuing her passion for art, taking evening classes at the School of Industrial Art in Philadelphia. Neel's parents did not understand her professional ambitions. "I don't know what you expect to do in the world," her mother once told her, "you're only a girl."

Early Training

With the help of scholarships and her own savings from her work as a secretary, Neel enrolled as a student in 1921 at the Fine Arts program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. There, she studied landscape painting under Henry Snell, and life drawing and portraiture with Rae Sloan Bredin. A brilliant student, Neel earned several awards for her portraits - which would remain her life-long focus. In 1924, she attended a summer program organized by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in the picturesque village of Chester Springs. There, she met and fell in love with a wealthy Cuban in the program, Carlos Enríquez.

Marriage to Enríquez marked the beginning of a devastating period in Neel's life. The couple married in Colwyn in June 1925 and several months later, they moved to Havana. The following year she had her first exhibition and gave birth to her first child, Santillana, who died while still an infant from diphtheria- the same disease that had claimed Neel's older brother. The couple moved back and forth between Cuba and the US, eventually settling on Manhattan's Upper West Side. They had another daughter, Isabetta, in November 1928, and planned to move to Paris in 1930. Instead, Enríquez moved suddenly and unexpectedly to Paris, taking Isabetta with him and leaving the toddler with his family in Europe. Neel suffered a nervous breakdown over the course of the following months, was briefly hospitalized, and later went to find Enríquez. When it was clear that the marriage was unsalvageable, Neel attempted suicide using the oven in her parents' kitchen, and was hospitalized again. Neel never divorced, but remained estranged from her husband, and would see her daughter only on rare occasions for the rest of her life.

Mature Period

Neel continued to live and work in New York City, and in 1933, received funding from the Public Works of America Project (one of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) initiatives enacted under President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal). During the depression, Neel became an activist for left-wing political causes. The WPA supported her painting - albeit with periodic interruptions in her funding - until 1943, after which she struggled to make ends meet for the rest of the decade. She participated in only one exhibition, and had difficulty finding a market for her work. In 1944, she even bought back some of her own paintings that were sold to a Long Island junk dealer for four cents a pound (along with other unwanted WPA works).

Neel never remarried, but had a number of romantic relationships beginning in the 1930s. In 1939 she had another child, Richard, with the nightclub singer Jose Santiago Negron. The most enduring of these relationships, lasting over two decades, was with the photographer and documentary filmmaker Sam Brody. Brody and Neel had another son, Hartley, in 1941, whom they raised along with Richard. In general, Neel's partners were unsupportive of her creative endeavors, and one was actively destructive: Kenneth Doolittle destroyed three hundred of her drawings and fifty oil paintings in a jealous rage when their relationship turned sour.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Neel saw the rise of Abstract Expressionism in New York, but remained steadfastly committed to representational work. She was interested in real people - flaws and all - not just bohemians and fellow artists. Her portraits from the 1950s strove to capture the character of her friends and neighbors in New York's Spanish Harlem in careful, expressionistic detail. This dimension of her work reflects the artist's commitment to left-leaning causes. The prominent communist writer Mike Gold recognized the value in the diversity of her human subjects - showing a broad slice of life in New York, and helped organize several exhibitions of Neel's work.

Some thirty years into her career, Neel finally began to receive the recognition she had long deserved. According to the artist, her work "began to be understood in the late 1950s, before that it was too tough for people." Though she remained resolute about the kind of art she wanted to make, she was always open to new ideas. In 1959, she appeared alongside Allen Ginsberg and Larry Rivers in the Beat film Pull My Daisy, based on a play written by Jack Kerouac. In the spring of 1960, she painted the poet, art critic, and MoMa curator Frank O'Hara over the course of five sittings, and produced two portraits, one of which was flattering, and the other shockingly critical. The paintings were well received, attracting the attention of ARTnews and the New York Times. This marked the beginning of Neel's commercial success.

Toward the end of the 1960s, the momentum of the women's rights movement led to increased interest in Neel's work. Neel was a feminist icon, but the enduring pragmatism with which she had always approached her professional life, with and without the support of feminists, is illustrated by the following example: In 1970, she was commissioned to paint the younger feminist activist Kate Millett for the cover of Time. Millett refused to sit for the portrait (her problem was not with Neel, but with Time magazine, a mainstream publication she did not support). Unfazed by this act of protest, Neel went ahead and painted her anyway, based on a scowling photograph. The portrait completed the assignment, and did justice to the anti-establishment activist's rage (which must have been considerable when she saw her portrait appear on the cover of Time).

Late Period

Largely due to feminist intervention in the history of art, by the 1970s, Neel was widely recognized as a major American artist. She was the subject of a major retrospective at the Whitney in 1974. President Carter presented her with an award for her contributions as a woman in art in 1979. She traveled to Moscow in 1981 for a major exhibition of her work, and was honored by New York's Mayor Ed Koch in 1982. She delivered lectures and participated in panel discussions at a number of prominent museums, art schools, and universities, and actively protested the Vietnam War. Her son Hartley and his wife constructed a studio on their property in rural Vermont for Neel to use during her frequent visits, and her personal life continued to be full. She became a grandmother several times over, and her former lover, John Rothschild, moved into her guest room.

While her creative energies seemed limitless, Neel fainted several times in 1980 and was given a pacemaker. During a routine appointment to check the device, doctors discovered advanced, inoperable colon cancer. Despite failing health, she continued to paint and visit Vermont to spend time with her children and grandchildren. In 1984, she appeared on the Tonight Show and insisted that the host, Johnny Carson, come to visit her and sit for a portrait. She died the same year at her New York apartment, surrounded by family and friends. Allen Ginsberg composed and read an original poem for her in a memorial service at the Whitney. She was among the few women artists of her generation who lived to see a major retrospective of her work. Alice Neel is buried near her studio in Vermont.

The Legacy of Alice Neel

Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Kathe Kollwitz come to mind as stylistic precursors for Neel's interest in portraying psychic depth that goes beneath the surface. In a world where painted portraits were still primarily for the upper class, Neel's insistence on representing a broad cross-section of the American public, from a range of racial, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds was firmly rooted in her political convictions, and recalls the staunch radicalism of Diego Rivera and American artists of the Harlem Renaissance from Aaron Douglas to Archibald Motley. Her interest in the details of time and place aligns her with documentary photographers like Gordon Parks, Berenice Abbott, Dorothea Lange, and Helen Levitt, all of whom worked for the WPA at roughly the same time as Neel.

Although rarely aligned with Neo-Expressionism, Neel's return to the figure, emotive brushwork, and penetrating insight into human psychology anticipate the movement several decades ahead of its time. Neel's broad impact on the art of today is evident in the work of major portraitists from Chuck Close to Lucian Freud. Elizabeth Peyton's eclectic, egalitarian focus on a broad cross-section of society, and South African artist Marlene Dumas's unflinching view of political and social issues are strongly indebted to Neel. Countless other painters have learned valuable lessons from her work.

Finally, Neel's life-long project to study humanity by means of closely examining the broadest array of subjects informs photographers and documentarians in the age of the internet. Her interest in the human condition of New Yorkers wherever she might find them is closely aligned with the ongoing project Humans of New York (HONY).

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Alice Neel

- Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting PrettyOur PickBy Phoebe Hoban

- Alice NeelBy Patricia Hills

- Alice NeelBy Ann Temkin