Summary of R. Buckminster Fuller

Aptly described by one commentator as a "practical dreamer", Fuller was a tenacious optimist, stating that his overall objective in life was to help achieve "humanity's comprehensive success in the universe". Fuller produced theoretical contributions to science, architecture, and design that were defiantly utopian. Intent on improving the quality of everyday living, his futuristic "Dymaxion" designs included a car, a house and a world map. These were followed by his Geodesic Dome which remains his most resounding practical success.

Fuller's worldview was shaped by an unshakable belief in the benefits of technology but he did not consider himself an inventor. He referred to himself rather as a "comprehensive, anticipatory design scientist"; that is, a modern day soothsayer who produced blueprints and prototypes which next generation design practitioners could take forward and realize. His idea that the Earth was analogous to a spaceship ("Spaceship Earth" as he called it), led to his most ambitious vision of all, a global network of Geoscope screens on which friendly nations would cooperate for the greater good. Fuller also earned a reputation as a mesmeric teacher and he supplemented his various internships and professorships with some 30 book publications. The spirit of Fuller's ambitious optimism and inventiveness was inspirational and lives on in the attitude of many present-day entrepreneurs, designers, architects and scientists.

Accomplishments

- Though his Geodesic Domes would prove too futuristic for everyday living, they found many other practical uses. Used as bases by the military around the world; as weather and radar outposts; as storage depots; as a home for botanical gardens and aviaries; and a fixture of many children's play areas, the Dome would become Fuller's abiding signature on the earth's landscape (as many as 200,000 have been constructed).

- Fuller's Dymaxion designs offered a whole new way of imagining urban living. His car, which would in the future take to the air or the sea; and the house, which would be mass produced and transported to their location in giant tubes, seemed to belong to the realms of science fiction. But the Dymaxion philosophy, which prioritized sustainability through technology and human-centric living, would in fact anticipate the central tenets of all modern design thinking.

- His revolutionary "island earth" Dymaxion Map - the first flat map of the earth's whole surface area - brough the Buckminster Fuller name to the attention of the American public. Like his Dymaxion Car and House, many viewed his futuristic vision as impractical and outlandish. But Fuller's map inspired legions of followers, some of whom shaped the whole future of world mapping.

- Fuller's World Game concept embodied his "Spaceship Earth" metaphor whereby the earth's population would work - or rather "play" - together for the collective benefit of the whole planet. With his blueprint for a city-enveloping Geoscope screen and a World Game (the latter to be played out on the former) Fuller had in fact foreseen a new technological utopia of advanced screen science on which global information and new ideas could be shared instantaneously.

The Life of R. Buckminster Fuller

In his vision for a "shelter for living", Fuller rued, "let architects sing of aesthetics that bring Rich clients in hordes to their knees"; for me "a home, is a great circle dome where stresses and strains are at ease".

Important Art by R. Buckminster Fuller

The Dymaxion Car

Fuller's futuristic vehicle was a total reimagining of family travel. With its engine positioned in the rear, the three-wheeled aerodynamic "Zeppelin" car was big enough to carry a dozen passengers (and a picnic), ran for 30 miles on a single gallon on alcohol fuel, and featured air nostrils, air-conditioning and rear view periscopes. Fuller also considered the comfort of his passengers, allowing for them to maintain an "inertial poise" while in motion. Never intended for mass production - only three prototypes were ever produced - Fuller goal was to present his vision as what "flying cars" might look like once they took to the "ocean of the sky".

Fuller, with help from his close friend, the Japanese-American landscape architect Isamu Noguchi, had started designing the car in the late 1920's, but had to wait several years to secure the funds needed to realize his vision. The prototype was built in a factory in Connecticut in 1933. It was to be the middle stage in a technical revolution that might result in a vehicle that could be airborne, road bound and even sea fairing. Whether or not it was an effective mode of road travel at the time was of little consequence to Fuller who wanted rather to inspire other designers. And inspire it did, enthusing the cream of 1930s American society, including Amelia Earhart, Henry Ford and Diego Riviera, and many years later, the famous British architect Norman Foster.

The three Dymaxion prototypes suffered different fates. Due to high interest from the media, the first Dymaxion was involved in a fatal accident at the gates of the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. Fuller biographies tell it that, overeager to get a first-hand look at what some elements of the print media had branded a "freak car", a Chicago South Park Commissioner accidentally drove his own car into the Dymaxion which rolled over, killing the driver and injuring its passengers (including a Scottish spy and French government minister). The Commissioner's car was hastily removed from the scene, and once the police arrived, the "clumsy" Dymaxion design was blamed for the accident. The first Dymaxion prototype was repaired, but was later destroyed in a refuelling accident; prototype three was cut up for scrap metal, while prototype two was thought to have been lost forever until it was discovered on a farm by a group of Arizona State engineering students. The farm owner had bought the car many years earlier for a dollar and was using it as a makeshift chicken coop. The last original Dymaxion Car was acquired circuitously by casino magnate Bill Harrah who restored it to its original glory and placed in on display at his National Automobile Museum in Reno.

Sheet aluminium on ash wood frame - National Automobile Museum, Reno

The Dymaxion Map

First published as an article in Life magazine in March 1943, Fuller's map eradicates much of the distortion than effected earlier maps. He wrote, "for the layman, engrossed in belated, war-taught lessons in geography [...] The Dymaxion World map is a means by which he can see the whole world fairly at once". The map was presented as a pull-out section that allowed Life's readers to assemble the map into a globe. The globe's surface is seen thus as a continuous surface without bisecting areas of major land mass. As the Open Culture journalist Josh Jones put it, the map "was intended to be folded in different ways though in its most common orientation it shows an archipelago of almost uninterrupted continents and allows the plotting of migratory paths and flow particularly well". The Buckminster Fuller Institute stressed, meanwhile, that the map was "the only flat map of the entire surface of the Earth which reveals our planet as one island in the ocean, without any visually obvious distortion of the relative shapes and sizes of the land areas, and without splitting any continents".

In spite of his enormous ambition, many of Fuller's contemporaries found his view of the world, expressed through his overarching "spaceship earth" analogy, romantic and impractical. Elizabeth Kolbert of The New Yorker summarized the sceptical attitudes towards his projects (which were only heightened following the unveiling of The Dymaxion Car) when she noted that his "schemes [...] had the hallucinatory quality associated with science fiction (or mental hospitals)". Yet these reservations seem somehow unjustified given that Fuller presented himself, not as an inventor at all, but rather as an "anticipatory design scientist" who promoted the maxim, "if you want to teach people a new way of thinking, don't bother trying to teach them [...] give them a tool, the use of which will lead to new ways of thinking".

In this sense, Fuller's "tool", the Dymaxion Map (and Fuller's modified icosahedron Airocean world map which was published in 1954), can be claimed as an unqualified success because it prompted many imitators and instigated nothing short of what Jones called "a revolution in mapping". It led indeed to maps based on ice, snow, glaciers and ice sheets, maps that illustrate flight paths and, later still, to the "Googlespiel", an interactive Dymaxion map developed by Google Maps. One might add that the design also extended its influence to the world of contemporary art through Jasper Johns's painting Map (1967).

Paper

The Dymaxion House

Fuller's idea for new living solutions was conceived of as early as 1928 with a design he named the "4-D house". At the time he was destitute and the idea was roundly dismissed as a viable economic venture. Undeterred, Fuller pushed on with his development until it was picked up in 1944 by the U.S. government which was looking for ways to keep wartime aircraft factories busy. Because of bureaucratic interference, The Dymaxion House, in spite of securing several thousand advanced orders, was only ever developed into one fully working prototype (the Wichita House).

The Dymaxion House was mathematically precise and polished; designed to be delivered fresh from the factory floor and flat-packaged so that it could be easily shipped world-wide. The height and shape of the house would prevent flooding and protect against earthquakes, and the octagonal symmetry would streamline the plastic shell so that it could withstand a tornado. The design was streamlined in order to optimize the internal climate which was also controlled by floor and roof vents that allowed for natural air conditioning in summer and efficient heat influx in the winter. In what at the time seemed like pure science fiction, Fuller thought of automating appliances with devices such as an instantaneous dishwasher and the shower replaced with a water-saving "fog gun". The fuel for the house was to be derived from human waste in order to achieve a sort of self-sufficiency to the home while it used tension suspension from a central column (which allowed for a change in floor planning - a bedroom could be squeezed to allow for a bigger living room for parties for instance) with the lightweight structure able to be airlifted to a new location as-and-when desired. The Dymaxion House was, finally, to be leased, or priced like a car, and paid off in instalments over five years.

Architectural historian Peter Reed, writes, "The unconventional shape, structure, and materials of the Dymaxion House stood in sharp contrast to buildings by leading modernists such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. Le Corbusier had described his own mass-produced housing as a 'machine for living in,' and the Dymaxion House was unabashedly machine-like, but Fuller was highly critical of modern European architects, who he felt were preoccupied with cosmetic concerns that merely symbolized or aestheticized functional elements without a clear and honest display of function and efficiency". Reed also observed that Fuller's prototype "inspired many architects" though some accused him of being "overly technical". Fuller himself took exception at that criticism, insisting, "I never work with aesthetic considerations in mind, but I have a test: if something isn't beautiful when I get finished with it, it's no good".

Aluminium sheet metal shell on a stainless steel strut - Wichita, Kansas

Geodesic Dome

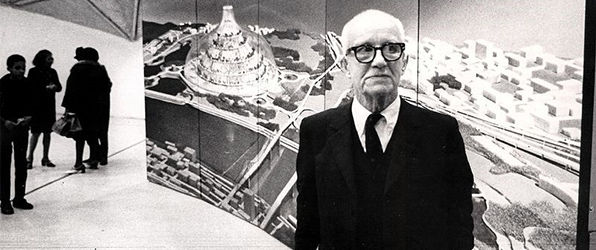

Fuller gained full acceptance amongst the international architectural community following the 1954 Milan Triennale at which he claimed the Gran Premio, the event's top prize. The Triennale's mission was to present the most innovative achievements in the fields of design, crafts, architecture and city planning with the theme for 1954 being "Life Between Artifact and Nature: Design and the Environmental Challenge". Fuller's 42-foot paperboard Geodesic Dome came with simple printed instructions on how the Dome could be shipped and assembled. It was Fuller's first significant success with the Dome which he had begun working on, with help of the artist Kenneth Snelson, in the late 1940s. According to the BBC science journalist, Jonathan Glancey, Fuller had till now been mostly considered "a practical dreamer" but "what fascinated architects was Fuller's claim that the geodesic dome offered the greatest volume for the least surface area, a case of doing very much more with very much less".

The Geodesic Dome was based on a triangular structure of rods. The surface area of the structure was minimal in comparison to the internal volume; it provided, in other words, a solid structure of unparalleled strength that allowed for a living area that was more open and spacious than regular housing designs. In light of the postwar housing crisis, and the lack of availability of new building materials, Fuller created what was a workable, cost effective housing solution. Added to that, the structure benefitted from less exposure to outside temperatures thanks to the nature of its spherical shape, and yet it also worked to concentrate heat within, resulting in a substantial energy reduction. Notwithstanding the practical issues of how a modern nuclear American family could divide up the dome's space to everyone's satisfaction, and how would existing furniture fit into a structure formed of continuously curved and sloping walls, Glancey pointed out, that few people "either then or now wanted to live in a dome that looked as if it would have been more at home on Mars than Dallas or Des Moines".

Though the Dome never took off as a domestic housing option (Fuller and his wife did live happily in a geodesic dome in Carbondale, Illinois) the US Marine Corps commissioned thousands of small geodesic domes that were delivered to the military around the world by helicopter. Meanwhile, larger domes were put to use as weather stations, long range radar stations and storage depots. The most impressive of the Domes in scale, such as the Montreal Expo '67 Dome, the NASA Epcot Center and (the biggest of all at a height of 216m) in Fukuoka, Japan stand as monuments to Fuller's futuristic vision, while the first large Dome to make its impression on the general public was built for the 1964 New York World's Fair and which stands today as the aviary at Queens Zoo.

Steel rod structure with acrylic cells

Geoscope

Writing with his usual enthusiasm in his 1962 book Education Automation (itself a transcript of his lecture programme at Carbondale), Fuller predicted the following: "The new educational technology will probably provide also an invention of mine called the Geoscope - a large two-hundred-foot diameter (or more) lightweight geodesic sphere hung hoveringly at one hundred feet above mid-campus by approximately invisible cables from three remote masts. This giant sphere is a miniature earth". Applying the same logic he used on his Geodesic Dome, the Geoscope resembled that of an outdoor planetarium, or, rather, a giant world telescope. The gigantic transparent dome, with its inner and outer surfaces covered with closely-packed electric bulbs, was to be used to visualize current world events; anything from migration and climate patterns to warfare.

By adapting his dome structure, Fuller believed he could capture the world in microcosm by creating what would be in effect an artificial sky: "This giant, 200-foot diameter sphere will be a miniature earth -- the most accurate global representation of our planet ever to be realized" he declared. Fuller believed that being able to immediately visualise global events would be commensurate with following the same story in a newspaper or watching it in a brief coverage on the 6 o'clock news, only more immediately. The Geoscope was envisioned thus as a more feasible interconnection between a person living in, say, New York, and the rest of the world. It was an idea that overlapped with that of the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan and his famous (but somewhat less grandiose) "Global Village" theory.

Fuller had wanted his dome to benefit the work of the United Nations, but his humanitarian ideal was, if inspired, somewhat over-ambitious: "All the world would be dynamically viewable and picturable and radioable to all the world, so that common consideration in a most educated manner of all world problems by all world people would become a practical everyday -hour and -minute event", he proclaimed. Fuller had successfully conceptualised the accessibility, display and sharing of global news and data but it was beyond the technical reach of his age. He nevertheless envisioned, perhaps inspired, future developments in media and screen technology.

Proposal

World Game

Fuller had started to formulate a mental picture of his techno-utopian game as early as 1927. It was not until 1961, however, that the World Game was finally launched as the core curriculum at the new Edwardsville Campus at Southern Illinois University (SIU). The World Game was essentially a premise, one that would prompt students to think about their future responsibility towards interconnected global systems and natural resources and, in time (since as Fuller acknowledged, "to play it one needs the computer tools, which are not yet commercially available"), grow into global agents who could implement new ideas for future world economies, resource flows, and ecologies. Fuller's global vision quickly gained traction and was even adopted as a theme for the U.S. Pavilion at Montreal's 1967 Expo. And though it never came to fruition, by the turn of the decade Fuller was claiming, with some justification, that the World Game had become "the main tool in the design of an environment for planning where good thinking about Spaceship Earth could prosper".

The World Game itself was to provide a simulation for the planet and its resources where designers, scientists, artists, engineers, and possibly even political figures, could suggest policies on how, in Fuller's words, to "make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone". The Dymaxion Map provided the topographic playing board for Fuller's "learning game" and it would be projected onto a series of Geoscopes suspended over every major city on the planet as a way to share information and ideas that might make the world work for the benefit of the whole planet.

The sheer ambition of the game meant that it remained an academic exercise that existed largely in research reports, resource studies and group workshops. This fact, according Thomas Broussard Turner, director of Fuller Projects at Southern Illinois University, should not be allowed to diminish the importance of Fuller's vision. In his preface to Fuller's World Game Series: Document One (1971), Turner placed Fuller in a group with Shakespeare, Darwin, Newton and Einstein. He wrote, "Each of these men evolved a powerful script around which a cast of people gathered to test out [a] new metaphor, to enlarge upon it, if possible, and to ultimately form a production ensemble of gigantic proportions to achieve a new science of action in testing out [their] script. That is what a metaphor can do when it is powerful enough and when it is successfully delineated by the consummate artist of his era - that is what Buckminster Fuller has done with the design of his World Game".

Simulation

Drop City

While still in the process of developing his Geodesic Domes, Fuller collaborated with a number of contemporary artists in a special "Theater Piece" at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the Summer of 1952 (Fuller having taught there in the summers of 1948 and 1949). Later claimed as the first-ever "happening" event, it was a piece of performance art featuring "separate and unrelated activities". While Fuller acted, John Cage conducted a lecture (punctuated with lengthy silences), Charles Olson recited a poem, David Tudor played piano, Merce Cunningham danced and Robert Rauschenberg played records while his paintings were suspended and rotated above the audience. It was in fact through an attempt to create a piece of performance art that Drop City came to be some 14 years later.

In 1965 a group of University of Kansas art students, JoAnn and Gene Bernofsky, Clark Richert and Richard Kallweit, acquired a six-acre goat pasture on the outskirts of Trinidad, Colorado. Having been involved in one of Allan Kaprow's "happenings" in New York - happenings being a challenge to the category of fixed, or static, art that required that the viewer inadvertently participate in each event on the premise of bringing art into every-day living - Richert and Gene Bernofsky invented the concept of "Drop Art". It involved "dropping" small, colorfully painted, rocks from their apartment window in Lawrence (Kansas) into the path of unsuspecting pedestrians and to observe their reaction. From Drop Art they developed the much more ambitious project of a Drop City; a City situated in the sprawling barren no-man's-land between the American and Mexican border where creative individuals could "drop in" to create a "live-in sculpture".

Drop City's various buildings were based on Fuller's Geodesic Domes and the crystalline designs of Steve Baer (a pioneer in solar energy). The "Droppers" as they were labelled (the commune drew the interest of the media who interpreted the "drop" in Drop City as a reference to "dropping acid", taking LSD, and to "dropping out" of society) were short on building experience but they learned to build their colorful Domes which cost next to nothing, from salvaged materials. In 1967 Fuller himself honored Drop City with his inaugural Dymaxion Award. In his message of congratulation, Fuller wrote: "Gentlemen: I take great pleasure in informing you that you have won the 'Dymaxion Award' for 1967, for your remarkable initiative, spirit, and poetically economic structural accomplishments. Faithfully yours, R. Buckminster Fuller". Fuller's public profile was raised as Drop City garnered fervent international attention and inspired a whole generation of alternative communities (it is estimated that as many as 2,000 rural communes emerged across America). But the excessive media attention that Drop City drew led to overcrowding and by the early 1970s the world's first Geodesic Dome City was all but abandoned, left to transients.

Trinidad, Colorado

Biography of R. Buckminster Fuller

Childhood to Early Adulthood

The eldest of four children (two sisters and a brother) Richard "Bucky" Fuller (as he was affectionately known) was born to Richard Buckminster Fuller Snr. and Caroline Wolcott, in Milton, Massachusetts in 1895. His family had a reputation for producing a long line of non-conformists who were active in their support for many causes. The most renowned Fuller family member was Bucky's Great Aunt, Margaret (Fuller), a critic, teacher and woman of letters who co-founded The Dial, the principal publication for the Transcendental movement. Margaret exerted a positive influence over the boy who duly took his diagnosis of near-sightedness, aged just four, somewhat in his stride. Legend tells it that Bucky also built his first architectural model, an octet truss, out of dried peas and toothpicks around the same age. Growing up near Bear Island, on the coast of Maine, he also developed a young boy's fascination with the sea and with boat building in particular.

Fuller Snr. died suddenly of a stroke in 1910 and, as the eldest son, the expectation was that Bucky would soon assume control of his father's business interests. The Fullers were well connected, with a lineage that attached the family name to Harvard. Fuller seemed to be fulfilling familial expectations when he attended the University in 1913. However, he was expelled after a year for excessive socializing and for skipping his midterm exams. Following his expulsion, he crossed the border into Canada where he took work at a mill. Here he developed his fascination with machinery, learning how to service the mill's manufacturing equipment. Fuller returned to Harvard in the autumn of 1915 but was dismissed once more, this time for a "lack of ambition".

In 1917, Fuller married Anne Hewlett, the daughter of the American Beaux Art architect James Monroe Hewlett. In the same year, he joined the U.S. Navy, where he confirmed his aptitude for engineering by inventing a winch for rescuing downed airplanes from the sea. As a result, Fuller was recommended for officer training at the U.S. Naval Academy. In 1918, still aged just 23, Fuller was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. His rank gave him a first-hand insight into the world of new technologies. As an aide to the Commander of all transport in the Atlantic during the First World War, for instance, he was witness at the first ever transatlantic telephone call. It was also in 1918 that Anne gave birth to their first child, Alexandra. Tragedy struck four years later when Alexandra died. It was life-changing moment for Fuller who blamed the family's poor living conditions for his daughter's premature demise. He vowed to make it his lifelong mission to provide a better quality of housing for ordinary Americans, and in 1922 he faced civilian life as an entrepreneur.

Early Period

In 1926, Fuller and his father-in-law developed a new method of producing reinforced concrete buildings. The partners patented the invention (it would be the first of 25 patents attributed to Fuller) but unfortunately their design failed to generate significant commercial interest. A year later, following the financial failure of the construction company, a newly unemployed Fuller seriously contemplated suicide. Yet, in a moment of realization, no doubt helped by the fact he had become a new father to daughter Allegra, Fuller decided he had no right to end his own life, and committed instead to finding ways to use technology to "save the world from itself".

This period in Fuller's life saw him living in New York. He would paint the walls of a bohemian café in Greenwich Village in exchange for meals, and mixed socially with the playwright Eugene O'Neill and the artist and architect Isamu Noguchi with whom he developed a lifelong friendship and working relationship. Fuller made many scientific and mathematical notes and sketches during these early years and they reveal a simplicity to Fuller's designs that stayed with him throughout his life. In 1928, following a period of profound contemplation, Fuller distributed 200 mimeographed (xeroxed) copies of his essay "4D Time Lock", a business proposal explaining his plan for a new style of affordable housing. In it he wrote "These new homes are structured after the natural system of humans and trees with a central stem or backbone, from which all else is independently hung, utilizing gravity instead of opposing it. This results in a construction similar to an airplane, light, taut, and profoundly strong". It was signed under what would become his professional name: R. Buckminster Fuller.

Fuller applied the philosophy of his essay to practical designs. He presented a sketch of a "one town world" which offered a model for an inexpensive, mass-produced, home that could be delivered to locations all around the world by air. Originally called the "4D House", a wire structure that offered a completely practical living machine, was renamed the "Dymaxion House" by a department store that had a model of the house on display. The word "Dymaxion" was in fact coined by store executives and was then trademarked in Fuller's professional name. Based on the words "dynamic," "maximum," and "tension," it gave name to some of Fuller's most important inventions. The word would in fact become synonymous with his design philosophy of "doing more with less"; a maxim with no smaller aim than improving the standard of living for all humanity. In 1928 Fuller unveiled his blueprint for his Dymaxion Car, a three wheeled machine with a top speed nearing 200 km per hour and capable of carrying 12 passengers. With a manoeuvrability which allowed it to turn within its own length, and even though only three prototypes were ever produced, it was a remarkable conception that demanded the attention of the public.

Mature Period

In 1936 Fuller met Albert Einstein who is said to have been impressed with the science behind Fuller's vision. Fuller was already used to seeing his ideas in print. He had published Shelter magazine in the early 1930s, and between 1938 and 1940 he was the science and technology consultant for Fortune magazine. Fuller also published the first of some thirty books, Nine chains to the Moon in 1938. By 1940 Fuller had designed the prefabricated Dymaxion Bathroom and the Dymaxion Deployment Unit (DDU), a mass-produced mini-house modelled on circular grain bins. Though DDUs failed to catch on with the public, they would be used during the Second World War as a way of sheltering radar crews in remote locations with hostile climates. The DDUs would also provide the prototype for Fuller's famous round housing development. There was significant public interest in the Dymaxion House but because of obstacles with union contractors (who controlled rules governing access to public utilities), and differences between Fuller and the stockholders, no bank was willing to finance their mass production.

Fuller finally found national fame in 1943 after Life magazine made a feature of his Dymaxion Map (as a center page spread). It proved to be the best selling issue the magazine had published to date as readers were invited to remove the map and fold it into an icosahedron (twenty sided) globe. The map/globe, for which Fuller received a patent in 1946, was designed without any distortions in scale; Fuller's goal being to overcome the idea of a nation mentality and to promote the idea rather of a "one planet" society.

1948 proved a pivotal year in Fuller's career when he was invited to lecture at the radical Black Mountain College. The historian Katherine C. Reynolds wrote, "The events that precipitated the college's founding [in 1933] occurred simultaneously with the rise of Adolf Hitler, the closing of the Bauhaus school in Germany, and escalating persecution of artists and intellectuals in Europe. Some of these refugees found their way to Black Mountain, either as students or faculty". Reynolds adds that at that time the United States was itself "mired in the Great Depression" and that the founder of the college, John A. Rice, and an advisory board that included John Dewey, Albert Einstein, Walter Gropius, and Carl Jung, believed fervently that a "general liberal arts education" was essential for the "economic rebirth" of any democratic nation. It was with this in mind the college hired its first lead arts teacher, Bauhaus luminary Josef Albers. "Speaking not a word of English", writes Reynolds, Albers and his wife Anni "left the turmoil in Hitler's Germany and crossed the Atlantic Ocean by boat to teach art at this small, rebellious college in the mountains of North Carolina". Hired by Albers, Fuller attend the college over two seasons between 1948-49 and it was here he was able to put the final touches to his Geodesic Dome project.

Following the success of the Dymaxion Map, Fuller devoted his life and career to his Geodesic Dome (for which he secured a patent in 1954). Fuller's "shelter for living" was a lightweight, easily assembled, and cost-effective structure that efficiently distributes stress (without the need for supporting columns and walls) and which could withstand extreme weather conditions. Based on Fuller's faith in "synergetic geometry", the Geodesic Dome was the upshot of his radical discoveries about the balance of compression and tension in building construction. There seemed to be no limit to Fuller's vision who saw his dome as a universal and cheap form of shelter that could fit everything from private homes to whole cities. In 1953 Fuller designed his first commercial dome for the Ford Motor Company headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. The U.S. military soon followed, using the lightweight domes to cover radar stations at installations around the Arctic Circle.

In 1959 Fuller became research professor at Carbondale, Southern Illinois University (SIU) (he would work at SIU in other capacities until his retirement in 1975). He and his wife committed to spherical living by taking up residence in their own Geodesic home. His appointment fuelled his intellectual work and he fully committed to lecturing following Ancient Greek learning methods; the ethos of planting seeds of thought into young minds that might then blossom at some future date. He was an obsessive talker who conducted lectures of legendary length; sometimes running for as much as a day or more with only short breaks for refreshments.

Sometimes Fuller would express complex ideas in verse to make them more understandable. This led to a one-year appointment to the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry at Harvard. He complimented his teaching commitments with a number of publications throughout the sixties, most notable of which were Education Automation (1962); Utopia or Oblivion (1969) and, his most famous book, Operating Manual for a Spaceship also published in 1969. In the latter, Fuller (who had coined the phrase "spaceship earth" over a decade earlier) proposed that one would abandon any idea of nation states and replace it with a spaceship system which was run on a precious fuel that everyone had a vested interest in preserving, and which duly optimised and regenerated the experience of common human life.

1965 saw the appearance of Drop City on the American landscape. Drop City was the brainchild of a group of Kansas art students who wanted to create a new art scene in the barren setting on rural South Colorado. Conceived of as a "live-in sculpture", the Geodesic Dome was the structure of choice for the Drop City commune who constructed them at next-to-no cost from mostly found and foraged resources. Having won the inaugural Dymaxion Award in 1967, Drop City, drew the attention of the popular press who singled it out as a communal utopia, that quickly turned to a dystopia when it was overrun with transient Hippies seeking to "drop-out" of mainstream society. By the early 1970s, Drop City was all but abandoned as a sort of geodesic ghost town.

In the late 1960s, Fuller created World Game with input from the likes of the Scottish futurologist and Independent Group member, John McHale, and his long-time collaborator, the Japanese-American architect, Shoji Sadao, a large-scale simulation and series of workshops he designed around a large-scale Dymaxion Map. He conceived of it as a means by which humanity might utilize the world's resources with greater efficiency. But possibly the most famous of all Geodesic Domes (if one discounts the Dome's most widespread use was to in hundreds of children's playgrounds around the world) was the Dome that featured at the 1967 Montreal World Fair. As science journalist Jonathan Glancey noted, the "most impressive of all [Fuller's Domes] was the eye-catching US Pavilion at Expo '67, the World Fair held that year in Montreal. It captured the attention of futuristic architects around the world and especially the young architect Norman Foster who employed Fuller as a consultant to his adventurous and, ultimately, hugely successful London studio". The said same Dome gained international publicity nine years later when it was engulfed in flames. It was, however, only the acrylic panelling that was destroyed while the steel structure remained defiantly, and fully, intact (along with its inventor's reputation).

Fuller started to accumulate many honors by this time, including a fellowship of the Royal Institute of British Architects which awarded him its Royal Gold Medal in 1968. He also received the Gold Medal Award of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in the same year.

Late Period

Into his later years Fuller continued to teach tirelessly and he spent much of his time traveling around the world delivering lectures. Fuller viewed teaching as a two-way process and he gained a reputation for his extended conversations with students. The scientist and mathematician Michael Wiese recalls that Fuller would "cover the tablecloth in drawings of tetrahedrons and synergetics at dinner. It's as if it was his duty to share the planetary mission, so that awareness of his ideas would disseminate and successful human life would be achieved and generate endlessly". In 1972 he was named World Fellow in Residence to a consortium of universities in Philadelphia, including the University of Pennsylvania. He retained his connection with both SIU and the University of Pennsylvania until his death.

In January 1975, Fuller sat down to deliver the twelve lectures entitled Everything I Know. The lectures were captured on video and brought to life using the most advanced bluescreen (back projection) technology of the day. Props and background graphics illustrate the many concepts he visits and revisits, which include, according to the Buckminster Fuller Institute, "all of Fuller's major inventions and discoveries [...] his own personal history in the context of the history of science and industrialization" and a vast range of subject areas encompassing "architecture, design, philosophy, education, mathematics, geometry, cartography, economics, history, structure, industry, housing and engineering".

After being dismissed early in his career by the architectural and construction establishment, Fuller was finally recognized with several prestigious industry awards in the U.S. and overseas (he also received a total of 47 honorary doctorate degrees). In early 1983, Fuller received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Ronald Reagan, America's highest civilian honor. On 1 July 1983, at the age of 87, R. Buckminster Fuller died of a heart attack while visiting his wife in the hospital she was being treated at for the advanced stages of cancer. It is said that Bucky had always promised Anne that he would "go first". Anne died 36 hours later.

The Legacy of R. Buckminster Fuller

Whilst R. Buckminster Fuller may not be a household name, his vision has left its indelible stamp on the world, most obviously through his iconic Geodesic Domes. Indeed, The Boston Globe estimated that more than 200,000 of the Domes have been erected around the globe since their inception. His vision of the Geoscope and World Game, meanwhile, seemed to many outlandish and utopian but have, in our post-modern world of screens and information technology, proved little short of prophetic. His Dymaxion designs have proved equally prescient and have left "an immense impact" on the worlds of science and design according to Britain's most famous living architect, Norman Foster.

Fuller's Dymaxion Car has garnered a cult-like following amongst a whole range of people including car enthusiasts, architecture aficionados and environmentalists. Foster, who built his own Dymaxion Car in 2010, enthused, "The car is such a beautiful object that I very much wanted to own it, to be able to touch as well as contemplate the reality for its delight in the same spirit as a sculpture". But Foster observed that the car represented much more than a collector's object, it having "triggering research projects about designing a new urban vehicle of the future". Indeed, Foster was fully alert to the comparisons with the Tesla car in its fusion of car design with sustainable technology, and other parallels with "Google's current research to transform conventional cars into robotically controlled vehicles". Fuller's impact on world geography has been equally influential, providing inspiration for Hajime Narukawa's 2016 "near perfect" AuthaGraph map. Considered the most accurate world map to date, it divides the globe into 96 triangles, projects them onto a tetrahedron which can then be unfolded into a flat, 96 section, rectangular map. As Foster summed up, "Bucky was one of those rare individuals who fundamentally influenced the way that one comes to view the world [Fuller] was the very essence of a moral conscience, forever warning about the fragility of the planet and our responsibility to protect it [...] His many innovations still surprise one with the audacity of the thinking behind them". After Fuller's death, chemists discovered that the atom's carbon molecule were arrayed in a structure similar to a geodesic dome. In what is perhaps his most fitting epitaph of all, they named the molecule "buckminsterfullerene".

Influences and Connections

- Margaret Fuller

- Shoji Sadao

- Arthur Penn

- Kenneth Snelson

-

![Isamu Noguchi]() Isamu Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi -

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers - Eugene O'Neill

- Albert Einstein

- Bertrand Goldberg

![Transcendentalism]() Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism

-

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![Jasper Johns]() Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns ![Charles Olson]() Charles Olson

Charles Olson- Hajime Narukawa

- Ruth Asawa

- Futurology

Useful Resources on R. Buckminster Fuller

- The Dymaxion World of Buckminster FullerBy R. Buckminster Fuller and Robert Marks

- Buckminster Fuller: Anthology for the MillenniumBy Thomas T. K. Zung, Michael A Keller

- You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the FutureBy Jonathon Keats

- A Fuller View: Buckminster Fuller's Vision of Hope and Abundance for AllBy L. Steven Sieden

- Envisioning Architecture: Drawings from The Museum of Modern ArtBy Peter Reed