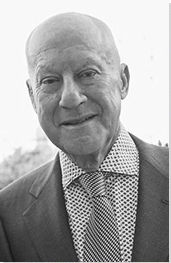

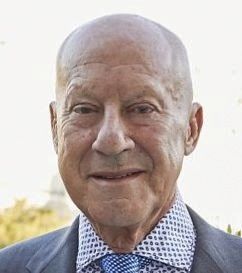

Summary of Norman Foster

Foster is arguably the world's most influential (and most honored) living architect. Something of a buccaneering figure whose spirit for personal adventure has spilled over into his professional life, he is guided by a strong sense of responsibility towards sustainability and the environment. Recognized chiefly for his jewel-like modern designs of steel and glass, and for a flair for smooth exterior contours and open, naturally-lit interiors, his designs stand out as landmarks in many of the world's greatest cities, including London, Berlin, New York, Hong Kong and Shanghai. The scope and vision of his ambition is evident in his involvement with an ongoing project in Masdar, a self-sustaining city in Abu Dhabi, while he is currently working in collaboration with the second superstar of world architecture, Frank Gehry, on a project to redevelop the site of London's famous Battersea Power Station (in which its four iconic chimneys will be left to stand).

Accomplishments

- Foster came to prominence at a dour time for British architecture. Turning his back on the concrete "utopias" of the post war years Foster managed to "shake up" the architectural landscape with unconventional, "lightweight" and "calm", designs formed of silver tubes and glass that allowed visitors to the building(s) to be at one with their immediate surroundings.

- Foster has been credited with reinventing the skyscraper and for pointing the way forward for future designers. By featuring spiraling geometric domes (in London), triangulated shapes (in New York) and tiered suspension structures (in Hong Kong) his skyscrapers stand as exemplars of the possibilities of how to invigorate uniform and congested city skylines.

- Blending old and new (though opposed to postmodernism for its lack of seriousness) Foster's interiors hark back to the "old" modern spirit of the Bauhaus's Walter Gropius in their detestation of "clutter". Indeed, celebrated within architectural circles as much for his pure and harmonious interiors as his exteriors, Foster's structures, including The Reichstag building in Berlin, conceal from plain sight every piece of internal plumbing and equipment.

- Having reinvented the skyscraper, Foster is credited with doing the same for the airport, first at Stanstead (UK), and then Beijing (China). Seeing the airport as a "reviled building type", Foster sought to create a space that celebrates the "poetry of flight". His terminals are filled with natural light and expansive views of the air traffic that encourages the traveler to enjoy an almost meditative pre-flight experience.

The Life of Norman Foster

Foster reimmagined the classical, 19th century Reichstag building in Berlin, filling this dome in glass and open air views. This is just one, although very popular, example of the amazing projects Foster has brought to fruition.

Important Art by Norman Foster

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts

The building was commissioned by Sir Robert and Lady Sainsbury to hold their impressive collection of art. Attached to the concrete buildings of Denys Lasdun's University of East Anglia, Foster was told to create an unconventional gallery to suit the Sainsburys' belief that the study of art should be an informal, pleasurable experience, not bound by the traditional enclosure of object and viewer.

Influenced by Mies van der Rohe's Nationalgalerie in Berlin, Foster wanted to create a gleaming silver tube, that literally and figuratively turned its back on the concrete-heavy architecture of the past. The Foster + Partners practice had been exploring lightweight, flexible enclosures, and Foster built on this, providing a vast glass atrium which hid all the structural and service elements of the building in the double-layer walls and roof. (He was to be so committed to this vision that he even hid door locks in the floor, so as not to interrupt the sleek finish.) Inside the shell is a sequence of spaces that incorporates galleries displaying works by Picasso, Bacon and Degas, alongside a reception area, the Faculty of Fine Art, a common room and restaurant. At the end of the building, looking towards the lake, are full-height windows allowing visitors within to see the work of Anish Kapoor, Henry Moore and Antony Gormley in the sculpture park beyond.

Architecture critic Deyan Sudjic wrote: "The late 1970s were a particularly bleak time for contemporary architecture in Britain. The soured [post-war] utopias of concrete social housing triggered a crisis of confidence. The Sainsbury Centre changed all that. Confident, strikingly beautiful and radical in conception, it pointed to a new direction." When Foster showed his creation to his friend Buckminster Fuller, "Bucky" asked: "How much does your building weigh Norman?" Foster, not knowing the answer, was stunned into silence. He later found out it was in fact 5,328 tonnes, but in the course of the calculations, Foster made a discovery concerning a building's harmony and balance that was to inform the rest of his career: "I realised the disproportionate amount of weight in the least attractive part of the building. It was an interesting voyage of discovery".

Norwich, UK

Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters

Sudjic stated that: "If you were to put the Sainsbury Centre next to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, you would see the difference between a glider and a jumbo jet [...] It is powerful and dynamic, where the Sainsbury Centre is calm and floating". The HSBC bank's chairman at the time, Michael Sandberg, said he wanted the best new bank building in the world. The tower was to act as a symbol of the bank's commitment to Hong Kong before the handover to China. As such, Foster had to be sensitive to cultural issues, as well as building a million square feet of office space in a relatively short timescale. Foster was fascinated with Feng Shui - Chinese geometry - and hired a geomancer to help with the project. The resulting tower saw him "reinventing the skyscraper". As Sudjic said: "It was the first time that anyone outside America made a skyscraper that looked like it was anything but a copy of an American."

The building relied on a suspension structure, with pairs of steel masts arranged in three bays. As a result, the building form is articulated in a stepped profile of three individual towers, respectively twenty-nine, thirty-six and forty-four stories high, which create floors of varying width and depth and allows for garden terraces. Inside is a ten-story atrium, providing workers with space and light from both sides of the flexible office space, as a vast mirrored "sunscoop" reflects sunlight down through the atrium to the floor of a public plaza below.

The HSBC bank saw Foster + Partners receive international critical acclaim, but it did not come without risk; the building was one of the most expensive made, required heavy borrowing and nearly bankrupting the architectural practice. The building has since become a landmark. As the Observer Magazine wrote: "In the congested centre of Hong Kong, the Bank unfurls from the sky, like a mechanised Jacob's Ladder, and touches the ground".

China

Reichstag, New German Parliament

The Reichstag building in Berlin was another project that was loaded with cultural sensitivity. Commissioned by Otto Bismarck 20 years after the unification of Germany in 1871 to celebrate the founding of the Second Reich, the building was torched by Nazi Stormtroopers in 1933 and assaulted by the Red Army in 1945. This history was not to be erased, Foster said when he won the commission to reshape it in 1992. He wanted to preserve the battle scars and graffiti left by Red Army soldiers - in his words,"to erase history is to refuse to learn from it". As well as creating a "living museum", Foster aimed to produce a sustainable and accessible building that was a significant democratic forum. As such, public and politicians enter the building together and the public realm continues in the eating spaces and the new cupola, built of steel and glass, that has since become a landmark, allowing "people to ascend symbolically above the heads of their representatives in the chamber". As Foster said: "The Reichstag was very much about creating the democratic forum for a reunified Germany [and] has become not only the symbol of the city but the symbol of the nation".

The glass cupola that crowns the building and illuminates at night both heralds its presence, and brings daylight to the building's inhabitants. Symbolizing rebirth, at the center of the great dome is an architectural feature that reflects light back down into the building, producing a dazzling, natural light chamber. This is its one of its best achievements, says architectural critic Jonathan Glancey: "Daylight falls on stone floors, stone walls, a solid, generous, clear-cut architectural expression in which, to date, there is no clutter, no evident gimmickry and where every bit of potentially messy equipment - heating, ventilation, loudspeakers, sprinklers, alarms - has been tucked into graceful sculpted units that march quietly, if determinedly, through the building". For Glancey, the Reichstag was a building that started life as an "ugly duckling that suffered terribly as it grew up, was abandoned, bodged up and ended up almost a swan".

Berlin, Germany

30 St Mary Axe

Affectionately known as the "Gherkin" (a small cucumber, usually pickled), 30 St Mary Axe has now become one of London's best-loved landmarks. Inspired by Buckminster Fuller's geometric domes, the building was commissioned by insurance company Swiss Re. Built on the site of the Baltic Exchange, which was destroyed by an IRA bomb in 1992, it has been described as "the most conspicuous eruption on London's skyline in a quarter of a century". In line with Foster's strict green agenda, the Gherkin is considered London's first ecological tall building, one that relies on a new rapport between nature and the workplace. The curved profile reduces wind deflection, helping to maintain a comfortable environment at ground level, and creates external pressure differentials which help drive a unique system of natural ventilation. Inside, the building has "lungs", social areas that draw in air and distribute it throughout the workspace. This, among other measures, means the Gherkin consumes half as much energy as a conventional office building. It's modernity however is matched by its nod to the classical; as art critic Jonathan Jones said: "Its expansiveness culminates in a dome that rhymes with that of St Paul's. Far from being a stranger on the London skyline, this is a shape that Wren, or Michelangelo, or any of the architects of the European great tradition would have recognised, admired and envied". The building was a critical success and won the RIBA Sterling Prize in 2004.

The tower's beauty, in the shape of its spiraling form and geometric dazzle, highlights the unattractiveness of the surrounding older buildings. Jones added: "It instantly exposes the banal ugliness of the NatWest tower or Canary Wharf. Because it has no British rivals, you have to go to New York to see how original Foster's tower is. It is comparable with the Chrysler building, the glorious art deco skyscraper built in Manhattan in the 1920s". Indeed, when it was first built, the Gherkin was a strange addition to a conventional skyline. But it has paved the way for quirky new designs, including the skyscrapers affectionately dubbed "the Walkie Talkie" building and "the Cheesegrater", along with ambitious new projects in planning. Jones added: "It is a masterpiece that opens new possibilities for world architecture".

London, UK

Hearst Headquarters

Two years after The Gherkin, Foster produced the Hearst Tower in New York. It was a challenge for Foster + Partners. He said: "It's Manhattan, New York, the city of Towers. You think of skyscrapers. The good news is that we have a tower in New York. The bad news is that it is a very, very small tower amongst the most extraordinary collection of mega towers. How do you make this tower have a presence when its physically so small?". He was limited by the existing six-story structure that publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst had built in the 1920s, and which was to provide the base for a soaring tower that was never built. As with the Reichstag, Foster had to design a building that joined the old and the new.

He came up with a design that saw a new skyscraper emerge from the Art Deco base like a work of sculpture. It's triangulated structure, with indented corners, used 20 per cent less metal than a conventional tower, reducing its environmental impact, and is made from 80% recycled steel. The new geometry was a hit with the public and artistic minds alike, and it won praise from artists Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra, Anthony Caro and Richard Long, the latter being commissioned to produce an enormous mural - which he realized in part by mixing mud from the River Avon in England and the Hudson River - for the building's interior.

Architectural critic Paul Goldberger was not always a fan of Foster's work. But on seeing the Hearst Tower, he said it was the most beautiful high-rise to be built in Manhattan since 1967. He wrote: "When the Hearst Building was finished, I called Norman 'the Mozart of Modernism' because I thought that conveyed the way his work seemed lyrical, elegant and effortless. And just as we know with Mozart, we know that there was a huge effort behind that but part of his genius was to produce this piece of music that didn't show the effort [...] Foster buildings tend to do that. They don't show the effort." New York magazine described the Hearst Tower meanwhile as "The best work of corporate architecture to grace New York in decades".

New York, USA

Beijing Airport

Foster has loved flight since he was a small child and he even held a commercial pilot's license. This passion culminated in his attempts to redesign air travel, beginning with London's Stansted Airport, in which he characteristically turned the terminal upside down, burying all the machinery underground, leaving light and airy atria through which people could walk unimpeded, and, in Sudjic's words "liberate travelers from the claustrophobic labyrinth of the traditional departure lounge". Foster continued this theme with Beijing Airport - which is now thought to be the largest building on the planet.

He said: "We are trying to reinvent concepts like the airport in such a way that the experience of an airport will be uplifting, where really an airport has got to a point in terms of crowds and security and so on that it is a kind of reviled building type". As such he included gently undulating roofs, high ceilings, natural light and long lines of vision that provide a relaxing, almost meditative experience for the traveler. The architectural language of Beijing Airport is both contemporary and rooted in Chinese culture. As Foster + Partners stated: "It is also a symbol of place, its soaring aerodynamic roof and dragon-like form celebrating the thrill and poetry of flight and evoking traditional Chinese colours and symbols". In Chinese fashion, from the outside it looks modest and unassuming, but inside the curved roofs soar, drawing in light and space. Artist Cai Guo-Qiang said: "When I go through, I look up and natural light fills the space and I find that often times there is no need for artificial light. It is an enclosed building but it is very soft and comfortable [...] It is the best I have ever seen".

Sudjic added: "The airport is a symbolic national front door, reflecting the aspirations of a culture, but negotiating the terminal is a stressful anxious experience for most passengers [...] A good airport celebrates travel, rather than makes the journey an ordeal. If you can see an airplane, a runway or the sky beyond, you have a natural orientation." It was another international hit. As the New Yorker said: "Foster has achieved what no other architect has been able to: he has rethought the airport from scratch and made it work".

China

The Masdar Initiative

Begun in 2014, the Foster + Partner Masdar City project remains ongoing and is being constructed in stages. The aim is to combine state-of-the-art technologies with the planning principles of traditional Arab settlements. Foster said of the project: "The environmental ambitions of the Masdar Initiative - zero carbon and waste free - are a world first. They [the Abu Dhabi government] have provided us with a challenging design brief that promises to question conventional urban wisdom at a fundamental level. Masdar promises to set new benchmarks for the sustainable city of the future".

The project is a specific response to the city's location and climate. The 640-hectare desert community is a key component of the Masdar Initiative and was launched by the Abu Dhabi government "to advance the development of renewable energy and clean-technology solutions for a life beyond oil". As seems fitting, the project has become home to the headquarters the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Masdar is linked to the adjoining Abu Dhabi communities and transport infrastructure though the city itself is the first community in the world to operate without fossil-fuelled transport. Never more than 200 meters from the nearest transport links, the estimated 50,000 denizens of Masdar will be encouraged to move about the city on foot while the shaded city streets and public spaces offer community hubs sheltered from the extremes of the desert heat. Divided into two sectors, the walled city is designed in a way that will avoid the "sprawl" that effects most urban areas. But the area surrounding the inner city - "the suburbs" for want of a better term - will contain wind and photovoltaic farms, research fields and plantations, enabling Masdar to become totally energy self-sufficient. Though designed specificly in mind to the city's geo-location, Masdar is intended to function as blueprint for self-sustained cities anywhere in the world. Now in his 86th year, Foster's boundless ambition shows no sign of abating as he has turned his thoughts now to the problem of revitalizing slum housing.

Biography of Norman Foster

Childhood

The only child of Robert and Lillian, Norman Foster was born in Stockport, Manchester in the industrial north of England. The family soon moved to a small, inexpensive rented terrace house in nearby Levenshulme from where the young Norman would draw the surrounding architecture. His father managed a pawnbrokers while his mouther was a waitress, and he credits them with passing on their indefatigable work ethic, though at a cost: "My parents worked and worked [...] They worked so hard that I wasn't really able to get to know them" he later observed.

The Foster household was cramped and damped, and he had a bath just once a week in a zinc bathtub in the kitchen but some of Foster's earliest childhood memories were of the Second World War: "I remember bombers going over in the middle of the night with my mother. I remember talking rationally about what kind of bomber it might be and then just breaking down into a flood of tears [...] abjectly terrified". He was also bullied as a child, singled out by school friends for his sharp intelligence. There wasn't much literature in the Foster household, but he frequently visited Levenshulme's Free Library where he read about Le Corbusier. He also spent much of his spare time making model airplanes and trains, and he became absorbed in children's construction kits like Meccano.

His parents scrimped and saved and were able to send their son to Dymsdale School, a local private primary, which saw him pass his 11-plus exam. This early academic success secured his entry into Burnage High School where he excelled in math and fell in love with art and architecture. Despite his strong aptitude, Foster regarded himself as an outsider in lieu of the fact that he was the only child among his peer group whose father worked menially (though, paradoxically, he was the only pupil to have progressed from a private school). As a teenager he would cycle out to the countryside, making the 130-mile round trip to the Lake District, igniting his lifetime love for cycling. His bicycle also took him to local architectural wonders, including the Jodrell Bank observatory in Macclesfield.

Early Training

In the industrial north of England, it was the norm for children to leave school and go into work at the age of 14. Foster bucked this trend by continuing with his studies; a decision that did not meet with the approval of his social circle. As biographer and architectural critic Deyan Sudjic wrote: "Foster would find himself buttonholed in the street by neighbors who regarded him as some kind of idler, still sponging off his parents".

At the age of 16 he was given a job at Manchester Town Hall, an uninspiring clerical role in the Treasurer's Department which he hated. However, it did give him a chance to study the architecture of Alfred Waterhouse, who designed the Town Hall, and the murals of Ford Madox Brown which were housed within its walls. Foster held the post for two years during which time he attended night school. He did not do as well as he had hoped, however, and on turning 18 he was compelled to undertake his national service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). He left the RAF in 1955, unsure of where his future might take him. Knowing he had to do something creative, he applied for a job at John Beardshaw, a local architect. Here he became "infatuated with design" and would stay late at the office so he could borrow and study from the drawings, slowly building up his own portfolio.

The following year Foster won a place on an architecture course at Manchester University. But he had to work hard to support himself, selling furniture, working in a bakery, and driving an ice-cream van. He later studied at Yale under Paul Rudolph who had been a student of Walter Gropius, the legendary founder of the Bauhaus. Yale was a "pressure cooker" and Rudolph was the man who taught Foster how to "draw like an architect". He also made Foster cry, telling him "You don't care enough" after he had been up all night working on a project. Despite this, Rudolph had spotted his pupil's potential and he pushed Foster more than his contemporaries. It was also at Yale that Foster met Richard Roberts and Carl Abbot, with whom he would move to London to form the short-lived collaboration Team Four. It was through Team Four that he met his first wife, the architect Wendy Cheeseman. One day while working together in 1964, they slipped off during a lunch break to tie the knot at a local registry office; celebrating with a picnic on Hampstead Heath straight after the ceremony. The following year Wendy gave birth to their first child, Ti, named after Jack Kerouac's family nickname. The family moved to Frognal, in North West London, where the couple became neighbors and friends of the sculptor Anthony Caro.

Mature Period

In 1966 Team Four designed the Reliance Controls building, a factory in Swindon which won them the Financial Times Industrial Architecture Award. But despite this success, the group had differences and it dissolved shortly after.

Soon after, Foster set up Foster Associates with Wendy, though in truth, Foster Associates was just a husband and wife team working from their Hampstead Hill Gardens studio. By this time Wendy was heavily pregnant with their second son, Cal, and their practice had evolved into Foster + Partners. The practice saw its first international breakthrough in 1979, when they won a competition to design the new Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation's (HSBC Bank) headquarters, their mission was to build "the best bank headquarters in the world". The building brought more critical acclaim and catapulted Foster + Partners onto the world stage. Lead by Foster, the practice went from strength-to-strength, putting its name to innovative buildings around the world, many of which have now become architectural landmarks.

In 1971 Foster formed a lifelong friendship and collaborative partnership with eccentric American architect and designer Buckminster Fuller. Foster credits him with bestowing on him a passion for the themes of shelter, energy and the environment, which Foster said "go to the heart of contemporary architecture", adding that, "For me, Bucky was the very essence of a moral conscience, forever warning about the fragility of the planet and man's responsibility to protect it".

In 1988 Foster suffered a terrible personal setback when Wendy was diagnosed with cancer. She refused conventional treatment and died a year later aged just 51; "It was a terrible time" Foster recalled (probably with a degree of understatement).

Late Period

Three years later Foster married jewelry designer Sabiha Rumani Malik. Malik became director of Foster + Partners, but the couple divorced four years later. (She later auctioned off her wedding ring and other jewelry that Foster had designed for her to raise money for charity.) In 1999 Foster was made a life peer at the House of Lords, following the recommendation of Lord Weidenfield and Lord Sainsbury, taking the name of Baron Foster of Thames Bank. Soon after, in 1996, Foster married his third and current wife, professor and publisher Elena Ochoa.

Foster has written several books about architecture and has been outspoken about design. He criticized postmodern architecture for not being serious enough, complaining that it could be too "gimmicky". He has also spoken out against "snobbery in architecture", saying that instead of being seen as fine art "wrapped in mumbo-jumbo" it should be recognized as an "all-embracing discipline taking in science, art, math, engineering, climate, nature, politics [and] economics". In 2010, meanwhile, he entered into a row involving the Prince of Wales who had tried to prevent the redevelopment of the old Chelsea Barracks site in London, complaining about the Brutalist modernist designs. Foster signed a letter, along with Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano and Pierre de Meuron criticizing the Prince for "using his privileged position" to "skew" the democratic planning process.

Foster is known to be motivated and passionate. He runs marathons, cycles and takes on extreme cross country races. He once wore the wrong gloves on a cross-country event and ended up with frostbite that took him six months to recover from. Undeterred, he completed the event the following year, and the year after that. He still races now, in his eighties. In 2005 he was diagnosed with cancer. He said: "That was horrific. Probably the worst moment of my life. One of the worst. I remember struggling through the 48 hours when I was rushed to hospital. I was told I was fortunate because it could have been a heart attack. Little was I to know that two years later I would have a heart attack. The thing that really was important to me was at the end of that six months I would still be able to train for the cross country ski marathon. I was told by the doctor to forget it. But I did it to the day, in six months. So I think a state of denial can be helpful. Later I was told I had maximum three months to live. That was the worst moment ever". He received chemotherapy, which he described as "pretty horrid", and was inspired by reading about Lance Armstrong and enrolling in cycle marathons. He came through that health crisis and is still working hard today.

![The Millau Viaduct in Southern France was described by then President Jacques Chirac as “a magnificent example, in the long and great French tradition, of audacious works of art [here executed by an Englishman], a tradition begun [...] by the great Gustave Eiffel”.](/images20/photo/photo_foster_norman_3.jpg)

The Millau viaduct in Southern France cut out five-hour traffic jams, thus reducing CO2 emissions, and Fosters + Partners has pledged to make all its buildings carbon-neutral by 2030. Foster is currently engaged on his most ambitious projects yet; Masdar (meaning "Source" in Arabic), a self-sustaining city in Abu Dhabi. The settlement promises to be carbon neutral, built from recycled steel and one that recycles all its own waste. In the words of the critic Sudjic: "What makes Masdar different from what is around it - the airport compound next door, the golf course, or the Formula One track - is that this is an experimental laboratory for a world that is waking up to the fear that it might be making itself uninhabitable". He is also working on the Tulip, an "inevitably controversial" concrete shaft topped by glass viewing platforms complete with slides and rotating pods to be built next to the Gherkin in the heart of the City of London.

Foster + Partners is currently working with Frank Gehry (the two superstars of world architecture) to redevelop London's iconic Battersea Power Station on the bank of the River Thames. It is a bold move - "starchitects" such as these do not usually collaborate - but the pair have cemented their friendship over many years.

The Legacy of Norman Foster

Foster + Partners has become a multinational practice producing works of public infrastructure, airports, civic and cultural buildings, offices and workplaces as well as private houses and furniture design. In 1999 Foster was made the Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize and the practice has also been awarded the Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize three times - for the Bloomberg Building, London, 30 St Mary Axe and the Imperial War Museum, in Cambridgeshire. Foster's legacy can be seen in many of the major cities of the world; his striking designs transforming the skylines of London, Berlin, New York and Shanghai. In recent years he has received some criticism - the Millennium Bridge joining St. Paul's Cathedral and Tate Modern had to be strengthened shortly after it was unveiled as it swayed so much it caused nausea amongst pedestrian; the wrong stone was said to be used in the south facade of the Great Court of the British Museum; while the opening of the Reichstag in Berlin was beset with technical problems - But Foster's influence remains almost unparalleled. As critic Steve Rose said: "With his playboy lifestyle, his tough-guy looks and his aggressively can-do attitude, he is the nearest thing we have to an architectural superhero".

For many, however, Foster's most important legacy will be in his determination to address issues of sustainability; his aim is to make better use of energy and to limit environmental impact. He also set up the RIBA Norman Foster Travelling Scholarship for architecture students and Foster + Partners says it takes pride in nurturing young talent across its studios around the world, employing more than 1,300 individuals. In 2015 Foster said he was proud that the average age of employees at the company was 32 - the same age as when he started the business.

Influences and Connections

-

![Frank Lloyd Wright]() Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright -

![Walter Gropius]() Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius - Joseph Paxton

- Serge Chumiaf

- Vincent Skully

-

![R. Buckminster Fuller]() R. Buckminster Fuller

R. Buckminster Fuller -

![Anthony Caro]() Anthony Caro

Anthony Caro -

![Richard Long]() Richard Long

Richard Long - Paul Rudolph

-

![Bauhaus]() Bauhaus

Bauhaus ![Modern Architecture]() Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture

- Architectural Modernism

Useful Resources on Norman Foster

- Foster + Partners Portfolio: 1967-2017By Norman Foster

- Norman Foster: A life in architectureOur PickBy Deyan Sudjic

- Norman Foster: ReflectionsBy Norman Foster

- Norman Foster: Selected and Current Works of Foster and PartnersBy Norman Foster

- Norman Foster: Works 6By David Jenkins

- Rebuilding the ReichstagBy Norman Foster