Summary of Concrete Art

Concrete Artists, following in the footsteps of movements such as Constructivism and De Stijl, offered an art entirely divorced from realistic subject-matter, based around precise and preemptive compositional structures, many of which represented mathematical or scientific formulas. In practical terms, Concrete Art was a movement of the mid-twentieth century: though it was given impetus by a manifesto penned by Theo van Doesburg in 1930, the term was popularized over the following two decades by the Swiss artist and designer Max Bill. By the 1950s, Concrete Art had grown into an internationally prevalent and immediately recognizable style, spreading outwards from its initial bases in France and Switzerland to find fertile ground all over Europe and, most significantly, in Latin America. The emergence of Neo-Concretism in Brazil in 1959 arguably signalled the demise of Concrete Art, but movements across a range of media, including Kinetic Art, Hard-Edged Painting, and Concrete Poetry, continued to bear the trace of its influence.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- One of the ideas underpinning the development of Concrete Art was that the artwork should refer to nothing other than itself: that is, that it should not represent external reality in any way. As van Doesburg put it in his "Basis of Concrete Painting", "[a] pictorial element has no other meaning than 'itself' and thus the picture has no other meaning than 'itself'." This emphasis is related to - but distinguished from - that of abstract art in the broader sense, wherein the initial stimulus for a painting and sculpture is often an external object or scene.

- In practice, Concrete Art's emphasis on non-representation meant that it often turned to intangible subject-matter such as mathematical and algebraic formulas and scientific theories for inspiration. In the Allianz Group fronted up by Max Bill in 1930s Switzerland, for example, artists would create paintings in which every possible visual combination of a pre-determined number of compositional elements was presented on the canvas, in fulfilment of a mathematical formula. Other artists such as Bill himself produced paintings and sculptures which visualized modern scientific theories such as space-time relativity. Though much abstract art had been moving in this direction since the 1910s, it was the Concrete Artists who brought to full realization the idea that a painting could represent, say, an algebraic formula rather than a person or an object.

- Like its ancestral movements Constructivism and De Stijl, Concrete Art transcended medium boundaries. Its most famous exponent Max Bill was an industrial designer and architect as well as a painter; in Latin America, the example of the Concrete Art movement inspired the development of modernist architecture, culminating in the construction of Brasília during 1956-60. At the root of this interdisciplinary agenda was the idea that the movement should proceed from compositional principles so elemental and universal that they could be applied to any medium.

- Though it divested itself of the task of representation, Concrete Art was deeply engaged with the social realities of its time, and often implicitly political. From its original base in Switzerland - a country whose neutrality during World War II ensured the movement's early survival - it grew to comprise an international language of visual symbols and logic, which spoke to a post-1945 desire to rebuild international cultural relations. In Brazil and Argentina in the 1940s-50s, Concrete Art became the symbol of an idealistic youth culture that sought to reconstruct society on more rational, humane lines.

Artworks and Artists of Concrete Art

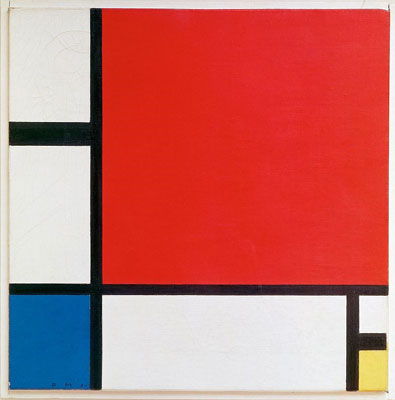

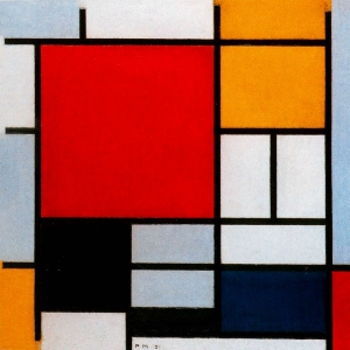

Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow

Though this painting was not conceived as a work of Concrete Art, Mondrian's vision of a universal compositional language rooted in a minimum of elements - horizontal and vertical black lines framing squares of white, red, yellow, and blue - summed up the spirit of Concretism avant-la-lettre. Moreover, the earliest works of Concrete Art were imbued with the spirit of Neo-Plasticism, and took their impetus from a manifesto penned by Mondrian's sometime compatriot Theo van Doesburg in 1930. In 1960, Max Bill mounted the exhibition Konkrete Kunst in Zurich in order to celebrate 50 years of Concrete Art's development, suggesting that the movement's primary polemicist was happy to incorporate early twentieth-century artists into its heritage.

A quintessential work of mid-century Concrete Art will often consist in the methodical visual expression of a mathematical formula. In a comparable spirit, Mondrian's Composition with Red Blue and Yellow was intended to express the mathematical forces underpinning all of sensory reality. In particular, the early development of Neo-Plasticism was heavily influenced by the theosophist and mathematician M.H.J. Schoenmaker's 1916 text Principles of Plastic Mathematics, in which he declared: "[t]he two fundamental and absolute extremes that shape our planet are: on the one hand the line of the horizontal force, namely the trajectory of the Earth around the Sun, and on the other vertical and essentially spatial movement of the rays that issue from the center of the Sun...the three essential colors are yellow, blue, and red."

We can see the results of this statement borne out in Mondrian's ascetic, non-symmetrical construction, in which abstract compositional elements come to stand for the essence of all life, while eschewing all specific subject-matter. In the works of Concrete Art produced in Europe and Latin America over the coming decades, this principle would be redefined through a more materialist worldview, and through more vibrant combinations of color and shape.

Oil and paper on canvas - National Museum, Belgrade, Serbia

Variation 14

In 1934, Max Bill, then in the early stages of defining the Concrete Art movement, began a series of artworks based on a simple geometrical exercise. He created an unfinished equilateral triangle whose third side would protrude out at a different angle to create a square, whose fourth side would protrude out at a different angle to create a pentagon, and so on (potentially ad infinitum, though Bill's formula stopped at the octagon). This simple mathematical principle was used as the basis for a series of lithographs which expressed the concept in a number of different ways: for example, by creating circles connecting up the shape's implied corners. In 1938 he published the series, asserting in his introduction to the Variations that "concrete art holds an infinite number of possibilities", even though "[s]uch constructions are developed only on the basis of their given conditions and without any arbitrary attempt to modify them."

This, in a nutshell, sums up the spirit of Concrete Art. Artworks were to be created which would express nothing more than the logic of their own creation, and yet within these rigid compositional constraints, as Bill put it, "an infinite number of very different developments can be evolved according to individual inclination and temperament." The large-scale series was a primary vehicle for this idea, and Bill created many serial works throughout his life, Fifteen Variations on a Single Theme (1934-38) being the first. This particular series also reflects his keen interest in color combinations. He had studied at the Bauhaus in the late 1920s under Josef Albers, the primary theorist of color in twentieth-century art. As vital to this work as its playful exploitation of geometrical constraints are the risks taken with tonal harmonies, with purples, oranges, greens, and pinks introduced into the primary color-palette in a number of the variations.

In 1937, during the creation of his Fifteen Variations, Bill founded the Allianz group of Concrete Artists in Switzerland, with compatriots including Richard Paul Lohse and Leo Leuppi. The Allianz Group was the first of many such Concrete Art collectives to spring up across the world during the 1930s-50s. Indeed, Concrete Art became as defined by its collectivist, internationalist spirit as by its commitment to compositional formulas.

15 lithographs - Daimler-Chrysler Collection, Berlin

Endless Ribbon

Max Bill was a sculptor, architect, and industrial designer as well as a painter. Indeed, his creative career, like that of his Argentine peer Tomás Maldonado, marked a gradual movement away from the canvas towards evermore large-scale and functional realisations of his principles. An early staging post on this journey was the creation in 1935 of his first Endless Ribbon sculpture, a later recreation of which is shown here. Based on the principle of the Möbius strip - a ribbon whose two surfaces run into each other - the series would occupy Bill continuously until his death in 1994, incorporating works in paper, metal, and stone.

In 1935, Bill was invited to design a sculpture to hang above an electric fireplace, potentially to be rotated gently by the upwards surge of hot air. He struck on the idea of a ribbon-shape whose opposing sides would merge with one another, mesmerized by this neat visual evocation of a mathematical conundrum. It was only after the work's completion that viewers informed him of its connection both to the Möbius strip and to the traditional figure-of-eight symbol for infinity. It is also easy to see the work as speaking to the recent discovery of space-time relativity, whereby two seemingly separate aspects of reality were revealed to be intimately related and interdependent.

If Concrete Art on the page was defined by playful, permutational works, in three dimensions it had the capacity to express mathematical and scientific concepts with a more singular and static grandeur. In later years, South American artists such as Gyula Kosice would advance this project by producing Kinetic Artworks influenced by the spirit of Concretism. Bill's Endless Ribbon stands at the forefront of such advances, evoking timeless and contemporary themes with an imposing grace.

Bronze - Middelheim Open Air Sculpture Museum, Antwerp, Belgium

Squares Formed by Color Groups

In this quintessential work of mid-century Concrete Art, Richard Paul Lohse, one of the co-founders of the Allianz Group, uses the canvas to express various visual possibilities of a methodical compositional formula. The canvas comprises a 4x4 grid of squares, each square consisting of three further, rectangular strips, with five different colors (blue, green, orange, pink, yellow) used to fill those strips, blue to appear in every square, the other four colors in every other. Further, complex principles of rearrangement and repetition define the terms of each color's appearance across the grid. The final effect of this formulaic process is, oddly enough, not stultifying but enticing, evoking something of the pleasure taken in pure logic and pattern, while eschewing all figurative content and precise suggestion of individual emotion.

Born in Zurich in 1902, Lohse trained as an advertising artist and graphic designer before co-founding the Allianz Group in 1937 with Leo Leuppi and Max Bill. 1943 marked a breakthrough year for Lohse, as he began to develop a range of algebraic systems through which he could compose his artworks. Some expressed in visual form the equivalent of the 'magic square' (a grid filled with numbers in which all possible horizontal and vertical sums add up to the same total). Others, like this piece, are based on a compositional logic requiring more concerted deciphering. Like Bill and the other Allianz artists, Lohse was also interested in exploring new color combinations; in this work we can sense the palette of Neo-Plasticism being expanded in exciting new ways, perhaps expressing something of the vibrancy of modern commercial design and advertising.

Lohse was also a politically committed artist, involved in the resistance movement during the Second World War. As such, he believed in the power of art's universal languages to foster intercultural harmony. Writing in 1988, artist Donald Judd surmised that "[t]he attitudes implicit in Lohse's work, including strong and still radical ideas about society, are very interesting, both as to what is older and what newer....In Lohse's work there is the end of the European compositional tradition, a good end, and also there is the beginning of much that is still beginning to develop."

Oil on Canvas - Richard Paul Lohse Foundation, Zurich

Desarrollo del Triángulo

This characteristic early work of Latin-American Concrete Art suggests the influence both of Max Bill's grid and systems-based composition and the spiritual abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky (who penned his own manifesto for "Concrete Art" in 1938). The title of the work translates as "Development of a Triangle", and we can almost 'read' the painting, starting at top-left, as a series of developments within a single line, dividing and diverging to form a number of triangular or proto-triangular shapes as it descends the canvas. As a co-founder of the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invencíon in Buenos Aires in 1945, Tomás Maldonado was associated with that wing of the Argentine movement that remained more committed to the compositional constraints and formulas of European predecessors such as Mondrian and van Doesburg. Nonetheless, the "system" underpinning this composition seems loose and improvisational, suggesting the scope for imaginative play within the limits Maldonado set himself.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1922, Maldonado rose to prominence through his co-editorship of the journal Arturo in 1944, the creative collaborations around which led to the founding of the Concreto-Invencíon and Arte-Madí groups over the following two years. Maldonado's artistic sensibility was entwined with his Marxist politics, and his sense that art ought to serve a functional purpose in society ultimately led him to abandon art for industrial design, just as his European peer Max Bill did. By this point Maldonado was working with Bill as one of the original faculty members of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. Maldonado later recalled that it was his desire to assist with the reconstruction of war-ravaged Germany that compelled him to abandon painting in favour of more socially useful pursuits.

Maldonado is best remembered today for his achievements as a designer and teacher at Ulm: through his work devising the school's "foundational course" he assumed a similar relationship to Bill, the school's rector, as László Moholy-Nagy had to Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus. However, Maldonado's early work as a painter and polemicist played a vital role in sparking off the Concrete Art movement in Latin America. His return to painting in the final two decades of his life shows how creatively significant it remained for him throughout his career.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Pintura Madí

Rhod Rothfuss's Madí Painting epitomizes the spirit of the eponymous group that he co-founded with Gyula Kosice and Carmelo Arden Quin in 1946. An irregularly shaped wooden board serves as the canvas, adorned with wild, mobile-seeming shapes, picked out in bright enamel. Though certainly a work of geometrical abstraction, Pintura Madí epitomizes the more anarchic spirit of the Arte Madí group as compared to Maldonado and the Concreto-Invencíon collective. Lines are more likely to be slant, with shapes echoing the seemingly random dimensions of the canvas, suggesting a creative process more open to chance and coincidence.

Born, like his Madí-group compatriot Carmelo Arden Quin, in Uruguay, Rothfuss moved to Buenos Aires in 1942, and was involved in producing the single issue of Arturo in 1944. After an initial period of collaboration with the Concreto-Invencíon artists, the two Uruguayan painters seceded, along with the Hungarian-born Gyula Kosice to form a group dedicated to the more ludic possibilities of Concretism. Quin and Rothfuss's work from the 1940s to the 1960s bears striking resemblances, suggesting a crucible of collective activity. Quin, like Rothfuss, created boldly colorful works on irregular wooden canvases suggesting a passing debt to the legacy of Central-American Muralism. Kosice, meanwhile, was an early innovator in Kinetic and Mechanical Art.

Rothfuss died in 1969, by which time the Madí group's initial period of creative ferment had come to an end. But its legacy had already been felt in the emergence of Neo-Concretism in Brazil at the close of the 1950s. This reflected a yearning amongst some South-American artists for a more intuitive, playful creative process than the constraints of Concretism yet allowed.

Enamel on wood - Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires

Ulmer Hocker

In many ways, Concrete Art remained more restricted to the traditional media of fine art - painting, sculpture - than its ancestral movement, Constructivism. While Constructivist artists such as Alexander Rodchenko always yearned to integrate art with functional design, Concrete Art was more likely to concern itself with the visual expression of abstract mathematical formulas, in an effort to remove itself entirely from the realm of figurative representation. Its "function", in this sense, was to assume a kind of autonomous presence in the world rather than to perform a useful task. But this was not always the case: many Concrete Artists, including the grandfather of the movement Max Bill, were also prolific industrial and commercial designers.

In the world of functional design, the goal Concrete Artists were more likely to set themselves was how to solve a given design problem using the minimum number of functional elements and constructive maneuvers. Nowhere is this ideal borne out more clearly than in the design of Bill's iconic Ulm Stool, created in 1954 for the students and faculty of the new Hochschule für Gestaltung. Intended to double as a wall-mounted storage unit, it is a masterwork of mid-century modernist design, achieving with an absolute minimum of physical parts and simplicity of construction in a versatile and functional form.

If the influence of Concrete Art in the world of painting and sculpture was in the emergence of Neo-Concretism and Minimalism in the 1960s, its legacy in the world of design can still be felt. It was at Ulm that the first examples of what we now call flat-pack furniture were created, for example, while its unprecedented focus on ergonomics and visual semiotics continues to inform commercial product design.

Wood - Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich

Silencio

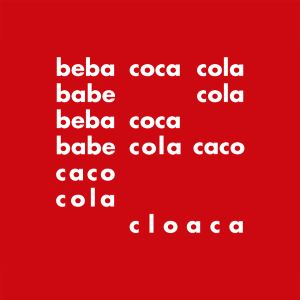

Eugen Gomringer's famous poem "Silence" - reprinted in a range of languages including Spanish, German, English and Hebrew since its composition in 1953 - represents an early attempt to resolve a seemingly impossible conundrum: how to bring the non-representative quality of Concrete Art to the medium of language. Words, more than visual or sculptural forms, must by definition refer to something other than themselves: so in attempting to make Concrete Poems, writers such as Gomringer were in a sense forced to reframe the terms of the problem. Works like Silence became exercises in exacting linguistic minimalism, radically reducing the semantic components used to convey their themes: in this case the idea or feeling of silence. At the same time, Concrete Poems assumed something of the visual or sculptural presence of Concrete Art through their appearance on the page: in grid-like or permutational patterns which drew attention to words and letters as things in themselves.

Born in 1925, the Swiss-Bolivian poet Eugen Gomringer was working at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm as secretary to Max Bill in 1955 when he established the international Concrete Poetry movement via long-distance communication with the Brazilian poets of the Noigandres group. Like Gomringer, the Brazilian poets had been forging the creative principles underpinning Concrete Poetry since the start of the decade, but their collective coinage of the term prompted the emergence of an international literary movement, spreading from South America to Japan. While the Noigandres poets were politically motivated and rationalist in their outlook, Gomringer's work generally offered a more spiritual, meditative vision.

The task that the first Concrete Poets set themselves - to bring to language the same clarity of form as a Concrete Artwork - ultimately proved to be nearly impossible. Nonetheless, the melding of Concrete Art's aesthetics with the literary heritage which its newfound advocates could draw on, resulted in a unique and fruitful development within the genre. Eugen Gomringer himself remains active, at 94, as the head of the Institut für Konstruktive Kunst und Konkrete Poesie in Rehau, Germany.

Konstellationen. Bern: Spiral Press, 1953

Bicho-Maquete 320

Lygia Clark's Bichos series (sometimes translated as "Little Beasts") are generally dated to the period between 1960 and 1964, shortly after Clark attached herself to the "Neo-Concrete" movement. A series of palm-sized sculptures constructed from hinged planes of aluminium, they are designed to be manipulated in the hand by the viewer. In these works, the principles of Concrete Art are pushed to a point of creative rupture. Though remaining (almost) in the realm of non-figurative abstraction, the construction process proceeds from an intuitive, sensory engagement with material and shape rather than a rational mathematical formula, while the viewer's (literal, physical) interaction with the work becomes vital to its final form, as they move the hinges and flaps to find a favorable position.

Born in Belo Horizonte, Brazil in 1920, Clark was involved with Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica in the formation of the Carioca art collective Grupo Frente in 1952. This, along with the formation in the same year of the Ruptura group in São Paulo, signified the emergence of a coherent Concrete Art movement in Brazil. But Clark and her colleagues were more inclined towards phenomenological, non-rational engagement with their materials and structures than Ruptura artists such as Geraldo de Barros. They were also more interested in the creative role of the viewer. Acting on these principles, at the close of the decade, Clark began exhibiting works such as the Bichos under the banner of "Neo-Concretism". One significant expression of her movement away from the strict abstraction of early Brazilian Concretism is the readmission of figurative suggestion into this work. Describing her army of little sculptures as beasts or critters, she likened the aluminium hinges to back-bones, as if endowing them with the pulse or spark of organic life.

In the years following the demise of the Concrete Art movement, Clark and her Neo-Concretist peers have ironically achieved far greater fame than the artists whose orthodoxy they supplanted. Clark's ideas of viewer-interaction and sensory hermeneutics, interdisciplinarity and the endless slippage of meaning from viewer to viewer, have proved more amenable to the landscape of subsequent contemporary art than the earnest rationalism of some of her peers. It goes without saying that her work also has value in kicking against an ideal of rational impersonality defined - as such ideals generally are - by male artists. Nonetheless, her work still emerged from, and stands as a monument to, the creative vigor of Concrete Art.

Aluminium - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings of Concrete Art

Constructivism

Concrete Art can trace its origins back to the early-twentieth-century movement of Constructivism, which in turn cannot be discussed in isolation from the invigorating effects of the 1917 Russian Revolution. Since the late 1900s, Russian artists such as the Suprematist Kazimir Malevich, and various individuals attached to movements such as Rayonism, Neo-Primitivism, and Cubo-Futurism, had been undertaking exercises in breaking down the picture plane and redefining sculptural form. This aim was shared with other movements across Europe, such as Cubism, but in the febrile political atmosphere of Russia in the mid-1910s it was increasingly pegged to a revolutionary political agenda. Non-figurative representation was seized on as a metaphor for the revolutions in thought and perception that the Revolution would usher in.

Amongst the many artists central to this yoking together of revolutionary and artistic sentiment were the sculptor Naum Gabo, his brother Antoine Pevsner, Varvara Stepanova and her husband Alexander Rodchenko, and Vladimir Tatlin. As significant as the revolutionary impetus of their work - and closely related to it - was a current of logical, scientific, anti-emotional thought. To these artists, non-figurative expression became a way of representing the objective scientific and mathematical forces that configured the universe's appearance to the naked eye. By representing those forces, their artworks would become the talismans around which Soviet society and psychology would construct itself. In their 1920 statement "The Realistic Manifesto", Gabo and Pevsner asserted: "we construct our work as the universe constructs its own, as the engineer constructs his bridges, as the mathematician his formula of the orbits". This basic sentiment remained at the core of much Concrete Art.

De Stijl and Neo-Plasticism

While Constructivism was being defined and debated in Russia, a group of artists based in the Netherlands were developing a geometrical abstraction of similar import, though with a more spiritual, less explicitly politicized value. Chief amongst them was the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, who, during the 1900s-10s, was influenced first by Seurat's Pointillism and then by Picasso and Braques's Analytical Cubism. Attracted to artistic styles that proposed universally applicable principles of composition - and committed to the logical dissection of the picture plane - he fell increasingly under the sway of the Theosophical movement. In particular, he was inspired by the Neo-Platonist mathematician M.H.J. Schoenmaker, who in his 1916 text Principles of Plastic Mathematics had proposed a system of mathematical forms underlying all perceptible reality, consisting of contrasting horizontals and verticals and the three primary colors.

The following year Mondrian, along with the Dutch artists Theo van Doesburg, Vilmos Huszár and Bart van der Leck, and the architects J.J. Oud, Gerrit Rietveld and Robert van 't Hoff, founded the journal De Stijl. It was dedicated to the newfound principles of abstraction that Mondrian had discovered in theosophical theory and mathematics, and which other group members had reached independently. Pioneered by Mondrian and dubbed "Neo-Plasticism", the style promoted in the journal was based on a strict, non-symmetrical arrangement of vertical and horizontal elements, with the color-palette restricted to black, white, red, yellow and blue. The aim, in short, was to forge a universal language for art that could unite peoples and cultures in the wake of the First World War. Like Constructivism in Russia, this new style was intended to transcend medium boundaries, with comparable principles being applied to design and architecture.

If Constructivism supplied the political and rational vigor of the Concrete Art movement, Neo-Plasticism provided an underlying spiritual impetus, while still being rooted in a utopian social vision, and in comparable principles of rational, geometrical abstraction. In practical terms, debates in and around the De Stijl grouping gave rise to the coinage of the term Concrete Art, as its most outspoken member Theo van Doesburg became increasingly frustrated with the strict formalism of Mondrian, and hunted out new forms and terminologies.

Theo Van Doesburg at the Bauhaus

Amongst the sources of friction in the Neo-Plasticist movement during the early 1920s was that Theo van Doesburg was increasingly engaged with the ideology of the Bauhaus school. Formed in Weimar in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus had by the early 1920s become the principle outpost of Constructivist aesthetics in Europe, particularly after László Moholy-Nagy took over the school's "basic course" in 1923. Van Doesburg gave lectures on De Stijl at the Bauhaus in 1921, and in 1922 moved to Weimar to integrate himself with the faculty. He was considered too dogmatic by Gropius to be offered a teaching post, but based himself near the institution, teaching interested students about Constructivism, Dada and De Stijl.

During 1912-14, Mondrian had lived in Paris, and in 1919 he returned there. In 1923 van Doesburg left Weimar for the French capital to be closer to him, but their physical proximity - previously, they had never actually lived near to one another - led to animosity. Introverted and esoteric, Mondrian was often affronted by the pugnacious, extroverted van Doesburg.

Van Doesburg was also becoming increasingly frustrated with Neo-Plasticism's insistence on the exclusive use of primary colors and straight lines. In 1926, he developed a style called Elementarism which introduced diagonals and mixed colors into the compositional lexicon: his Simultaneous Counter-Composition (1929-30) gives a sense of the distinctions which had emerged within the movement around De Stijl by that time. Mondrian, for his part, seceded from the group in protest.

Nonetheless, Mondrian and van Doesburg remained in Paris for the remainder of the 1920s, and it was partly their presence there which meant that the most vital developments in geometrical abstraction during that decade occurred within the city, culminating in the publication of Van Doesburg's "Basis of Concrete Painting" in 1930, just a year before his death.

Key themes

Art Concret: Movement, Magazine and Manifesto

As well as hosting a burgeoning abstract art movement, Paris in the 1920s was the center of Surrealism, spearheaded by the writer André Breton, which had emerged partly from the anti-rationalist spirit of Dada. Combining Dada's love of the inexplicable and other-worldly with an increasingly realistic method of representation, Surrealism stood for all that artists such as Mondrian and van Doesburg opposed. It was partly from this sense of collective opposition that various new groupings emerged in the late 1920s, committed to the cause of a rational, abstract art.

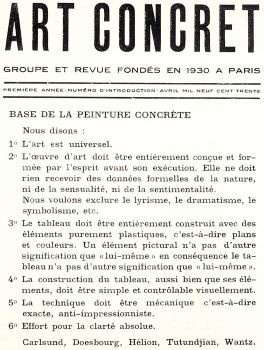

In 1929, the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García and the Belgian painter Michel Seuphor formed the group Cercle et Carré. Their aim was to bring together all artists committed to rational geometrical abstraction under an inclusive banner, but the dogmatic van Doesburg, who had initially been involved in discussions about the founding of the group, felt that it should be guided by more stringent principles. To that end, he formed the short-lived rival collective Art Concret, and in the single issue of its journal, Art Concret (1930), published what has since become known as the foundational document of Concrete Art:

We declare:

1. Art is universal.

2. The work of art must be entirely conceived and formed by the mind before its execution. It must receive nothing from nature's given forms, or from sensuality, or sentimentality.

We wish to exclude lyricism, dramaticism, symbolism, etc.

3. The picture must be entirely constructed from purely plastic elements, that is, planes and colors. A pictorial element has no other meaning than "itself", and thus the picture has no other meaning than "itself".

4. The construction of the picture, as well as its elements, must be simple and visually controllable.

5. Technique must be mechanical, that is, exact, anti-impressionistic.

6. Effort for absolute clarity.

"Basis of Concrete Painting" (1930) is a typically terse, polemical tract, calling in effect for a synthesis of all previous movements towards the rational expression of non-naturalistic subject-matter. Espousing a universal compositional language freed from emotional, spiritual, and subjective impulses, van Doesburg laid the groundwork for a movement that would divorce itself entirely from the expression of perceptual reality or symbolic meaning. Concrete Art was to be a language of pure form, signifying nothing more itself, defined on universally intuitable and logical principles. At the root of this ideal were both the rational and political idealism of Russian Constructivism and the esotericism of De Stijl.

In 1931, van Doesburg died of a heart attack, aged just 47. His manifesto thus stands as an unrealized statement of intent, and it was down to a younger generation of artists to bring his vision of Concrete Art to fruition. One of van Doesburg's last acts was to help found the group Abstraction-Création, which incorporated Cercle et Carré and Art Concret, uniting the sparring factions in Paris's community of abstract artists.

Max Bill and the Allianz Group

Following Theo van Doesburg's death, a figurehead was needed to spearhead the nascent Concrete Art movement. Although both Wassily Kandinsky and Hans (Jean) Arp penned their own manifestos for concrete art (in 1938 and 1942 respectively) it was necessary for this figure to emerge from the younger generation of abstract artists. Such a figure emerged in Switzerland in the form of the artist and polymath Max Bill. Born in 1908, Bill had studied at the Bauhaus during 1927-29, learning from artists including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and, most significantly, Josef Albers. In 1929, Bill moved to Zurich to set up a studio, focusing on sculpture, painting and architecture while he earned money as a designer.

Influenced by his Bauhaus tutors, Bill sought through his work to express scientific and mathematical formulas in intuitive and tangible forms, expressing as little as possible of his own emotional investment in his work, and eschewing 'subject-matter'. In this sense, his work was quintessentially Concrete. Nonetheless, Bill was twenty-five years younger than van Doesburg, and had no strong personal connection to him. His seizure on the term "Concrete Art" represented an act of homage, even appropriation. Still, it was primarily through Bill's endeavors over the next two decades that Concrete Art found widespread recognition and acceptance.

In 1937, Bill formed the Allianz group to promote Concrete Art, along with the artists Richard Paul Lohse and Leo Leuppi. The group held its first show in Basel that year, and subsequent exhibitions were mounted across Switzerland during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Switzerland's neutrality during the Second World War ensured the group's continued productivity while artists and writers fled from violence and persecution in nearby countries.

Some of the group's work - like Bill's Endless Ribbon series of Möbius strip sculptures - aimed to express the new scientific theories which defined modernity, such as space-time relativity. Others, like Lohse, used methodical visual arrangements to draw out all the possible visual expressions of a mathematical or algebraic formula. In all cases, the compositional aesthetic was meticulously neat, and the work entirely divorced from 'reality' as such. At the same time, the Allianz artists were interested in exploring tonal harmonies, and their work is often vibrantly colorful as compared to that of the De Stijl artists, for example. In the context of the Second World War, Concrete Art also had an implicit political impetus: in attempting to define a universally intuitable visual language, Concrete Artists were attempting to lay the groundwork for intercultural dialogue and empathy.

From the 1940s onwards, Bill increasingly turned his attention to commercial and industrial design, following in the footsteps of the Constructivists, who had sought to merge artistic expression with functional craftsmanship. In 1944 Bill cemented his own reputation and that of the movement by staging the first international exhibition of Concrete Art in Basel, by which time the style was spreading across Europe and beyond.

Developments in Europe, 1945-60

By the mid-1940s, groups influenced by Bill and the Allianz group's variant of Concrete Art had sprung up all over the world. These groups emerged organically, from a range of regional and national contexts, and expressed a huge range of creative impulses. But they were all buoyed by the internationalism of the post-war years, and united by an underlying interest in non-figurative expression, as well as an investment in science, maths and logic.

Limiting our focus to Europe, we can posit at least eight groups to emerge between the end of the Second World War and 1960. The earliest of these included Linien 2, founded in 1947 in Copenhagen, Movimento Arte Concreta, founded in Milan in 1948, Group Exat 51, founded in Zagreb in 1951, and Group Espace, founded in Paris in the same year. Amongst the significant artists of the post-war period to attach their names to these groups were the Danish Ib Geertsen, the Italian Alberto Magnelli (a former member of Abstraction-Création), and the sometime Orphist Sonia Delaunay.

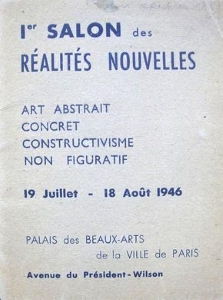

Paris remained a center of activity, with the first significant exhibition of Concrete Art following the Second World War held at the Gallerie René Drouin in 1945. This exhibition included the work of pioneers of Neo-Plasticism and other proto-Concrete movements, such as César Domela and Jean Gorin, exemplifying the tendency of Concrete Artists and theorists to claim developments prior to 1930 as steps in the advancement of the genre. In 1946, the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles was founded as a successor institution to the Abstraction-Création group: the new, Paris-based gallery promoted what it called "concrete art, non-figurative or abstract art".

In a sense, the Concrete Art movement in post-war Europe occupied a liminal space between a range of more famous contemporary genres, such as Kinetic and Op Art, and the last vestiges of pre-war geometrical abstraction. As such, it never developed the coherent character that it would elsewhere: specifically in the resurgent post-war cultures of Latin America.

Developments in Latin America, 1945-60

We might posit various reasons why the most significant developments in Concrete Art between the end of the Second World War and the start of the 1960s occurred in Latin America. One may be the newfound confidence that the major economies of Latin America, including Brazil and Argentina, had assumed in the aftermath of the war in Europe, shielded from its long-term effects while benefiting from the wartime economy. These countries had also welcomed an influx of European artists and theorists fleeing the conflict, while the appropriation of Realist and folk-art by authoritarian governments in Mexico and elsewhere led to a flight from an art of 'easy messages'. Since the 1930s, artists like Joaquín Torres-García (co-founder of Cercle et Carré) in Uruguay and Emilio Pettoruti in Argentina, had also been pioneering a regional traditional of geometrical abstraction.

An important early event in the emergence of Latin-American Concrete Art was the publication of the single-issue art journal Arturo in Buenos Aires in 1944, leading to formation of the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invencíon in the city the following year, and the Arte Madí group in 1946. Both groups were heavily influenced by De Stijl and European Concrete aesthetics, and both were committed to an art of pure geometrical abstraction. However, in Latin America Concrete Art also inherited something of the political vigor of the Russian Constructivist vanguard, its products often intended to stand for new forms of social and political organization. The continent was, after all, undergoing a period of rapid industrial, technological and social development; as such, Concrete Art became an ambitious, future-oriented genre.

The Asociación Arte Concreto-Invencíon was co-founded by Tomás Maldonado, a committed Marxist who believed that the logical forms of Concrete Art could form the basis for new models of societal organization and new psychological paradigms. As such, the Asociación artists - including Maldonado, Manuel Espinosa, Alfredo Hlito, Enio Iommi, Raúl Lozza and Lidy Prati - remained committed to a number of tight creative constraints. The Arte Madí artists - Gyula Kosice, Rhod Rothfuss and Carmelo Arden Quin - were also committed to the expression of modern life through Concrete Art. But their forms were more playful than those of the Asociación artists, moving more freely into the realms of sculpture, Kinetic and Light Art, and influencing the later emergence of Neo-Concretism in Brazil.

Following the emergence of the Arte Madí and Arte Concreto-Invencíon groups, similar collectives sprang up elsewhere, such as the Grupo de Arte No Figurativo in Montevideo, Uruguay, the Grupo Frente in Rio de Janeiro, and Grupo Ruptura in São Paulo. All three were formed in 1952, a year after a major retrospective of Max Bill's work in São Paulo had cemented his reputation amongst Latin-American Concretists. The latter two groups proved particularly influential on subsequent developments in Concrete Art. Grupo Frente included the artists Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape, all of whom were involved in the conceptualization of Neo-Concretism at the close of the decade. The Grupo Ruptura, meanwhile, laid the foundations for the emergence of Concrete Poetry - a kind of visual poetry influenced by Concrete Art - through their creative exchanges with the poets of São Paulo's Noigandres collective.

The construction of Brazil's new capital Brasília, during 1956-60, on principles strongly influenced by International Style architecture, Constructivism, and the country's emergent Concrete Art movement, shows the significance of the movement in Latin America. It was here, and not in Europe, that the principles of Concrete Art were most strikingly advanced at mid-century.

The Hochschule für Gestaltung

The most significant late development in Concrete Art in Europe was probably the formation of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, West Germany in 1953. Co-founded by Max Bill and Inge Scholl, sister of the murdered White Rose Movement leaders Hans and Sophie Scholl, the HfG was established as a successor institute to the Bauhaus, which had closed under Nazi pressure in 1933. As such, it was committed both to the cultural and moral rebirth of Germany and to advancing the principles of abstract art, functional design, and architecture. Again, the aesthetics of Concrete Art were integrated with a progressive political agenda.

Though the school had closed by 1968, many artists connected to the Concrete Art movement, including Tomás Maldonado and Josef Albers, were involved in designing or teaching courses at Ulm, and so the influence of Concrete Art was impressed upon a further generation of designers, architects, and artists. As such, and because of the HfG's interdisciplinary approach, the principles of Concrete Art remained in fruitful dialogue with functional design and architecture even at this late stage of its evolution. Nowhere is this more evident than in the design of the HfG campus itself by Max Bill, on principles strongly influenced by his aesthetic as an artist, and by International Style architecture.

The poet Eugen Gomringer also worked at the school, as a secretary to Bill (who was the Hochschule's first rector). In 1955, Gomringer hosted the Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari, a representative of the São Paulo based Noigandres group. This resulted in the development of Concrete Poetry, which took on its own tenor and character as it merged with developments in late Anglo-American literary modernism, serving as one of the Concrete Art movement's lasting legacies.

Later Developments - After Concrete Art

Neo-Concretism

With the inauguration of the São Paulo Biennial in 1951 and the mounting of a National Exhibition of Concrete Art in São Paulo in 1956, Brazil had established itself as one of the centers of the modern art-world, and of the Concrete Art movement in particular.

However, by the close of the 1950s, many Brazilian artists felt that Concrete Art had become inordinately narrow and inadvertently colonialist in its outlook, binding itself to strict rules of composition that were overly invested in rationalism, and tethered to the pre-war achievements of European artists. A number of artists involved in the Grupo Frente, including Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, and Hélio Oiticica began producing artworks more governed by intuitive, phenomenological interactions with materials and space, inviting more creative interactions with the viewer.

Their sentiments found collective expression through the writing of a poet, Ferreira Gullar, who was himself frustrated with the rationalistic approach of the Noigandres Concrete Poets Augusto and Haroldo de Campos and Décio Pignatari. In 1959, with the support of Pape, Clark, Oiticica and others, he published a "Neo-Concrete Manifesto" in the Jornal do Brasil, in response to an exhibition of Neo-Concrete Art recently staged in Rio de Janeiro:

We use the term "neo-concrete" to differentiate ourselves from those committed to non-figurative "geometric" art (Neoplasticism, Constructivism, Suprematism, the School of Ulm) and particularly the kind of concrete art that is influenced by a dangerously acute rationalism.

The Neo-Concrete movement was short-lived, as by the 1960s its founding members were moving into event-based and conceptual practices, but its influence has, ironically, been far more widely felt than the movement it supplanted. In placing the affective, sensory relationship between viewer and artwork at the center of its concerns, it predicted and helped to bring about a more general sea-change in modern art from the 1960s onwards; it was particularly analogous to the contemporaneous development of Minimalism in North America.

Kinetic Art

If Concrete Art in post-war Europe represented a reaffirmation of the principles of geometric abstraction within painting and sculpture, Kinetic Art - and the overlapping movement of Op Art - represented the extension of Constructivist principles into the realm of moving objects. Like Neo-Concretism, its heyday occurred around the time that the Concrete Art movement was waning. Nonetheless, it developed partly through dialogue with the older movement, and can be seen as an aspect of its legacy

By the 1950s, artists such as Victor Vasarely in France and Alexander Calder in the USA (and, slightly later, Bridget Riley in England) had applied their fascination with logical constructive principles and non-figurative form to artworks which gave the impression of motion, or which literally moved. In extending the artwork in time as well as space, they applied concrete principles of construction to a new dimension of expression, breaking down the established boundaries of geometrical abstraction.

Other artists, such as the French-Hungarian Nicholas Schöffer, produced Kinetic works powered by computers that would move in response to external stimuli - such as his CYSP 1 (1956) - heralding the emergence of Systems Art and Cybernetic Art. Concrete and Constructivist principles were extended into the realm of semi-autonomous machines, presented as artworks, or even as artists (CYSP 1 famously performed in a ballet). In the face of such developments, Concrete Art seemed increasingly staid in its ambitions. Nonetheless its advances prefigured and inspired those of Kinetic Art, which also drew in Concrete Artists such as Gyula Kosice.

Concrete Poetry

Like Constructivism, Concrete Art was intended to define compositional principles so elementary that they would transcend medium boundaries. One aspect of this vision was realised in the mid-1950s through the emergence of Concrete Poetry. Through the collective endeavors of the Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer - based at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm - and the Brazilian poets of the Noigandres collectives (consisting of the brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos and Décio Pignatari), a style of poetry was defined that spread across continents, and which responded to the compositional advances of Concrete Art. The first manifesto of Concrete Poetry was written by Gomringer in 1954, though its tenets were firmly established by the Noigandres's "Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry" in 1958.

The aim of Concrete Poetry was that words would be used in the same ways as the compositional elements of a Concrete Artwork, referring to nothing more than the compositional logic of the poem itself, and often presented in visual patterns borrowed from Concrete Art. Though this proved an almost impossible aim to realise in the long term, Concrete Poetry nonetheless inspired an international movement, with more clusters of Concrete Poets appearing across the world during the 1950s-60s - and in more locations - than had cells of Concrete Artists during the 1940s-50s.

Between 1968 and 1970, three major anthologies of Concrete Poetry appeared, signalling both the high-water mark and beginning of the end of the Concrete Poetry movement. Like the Concrete Art movement, its achievements had by this point been redefined by artists frustrated with the inherent limits of its rationalist programme.

Developments in North America, 1950s-60s

In 1950s America, a number of artists and sculptors turned against the romantic angst and mythologization of the individual that characterized its most successful post-war export, Abstract Expressionism. Many of these artists looked back to the examples of De Stijl and Constructivism for an artistic style based on more rational, impersonal principles. Since the 1930s, the USA had also welcomed a number of émigrés from Europe schooled in the principles of geometrical abstraction, such as Josef Albers, who left Germany following the closure of the Bauhaus under Nazi pressure in 1933.

Though Concrete Art was never as coherent and dynamic a movement in North America as in South America, individual artists such as Charles Biederman made distinctive contributions to the development of geometric abstraction in the 1940s-50s. Josef Albers's tenure as head of the painting programme at Black Mountain College from 1933 to 1949 also ensured that principles of logical, non-figurative composition influenced the development of North-American painting at mid-century.

Moreover, in a number of native North-American movements, particularly Hard-Edged Painting, we can sense a fascination with the internal dynamics of composition, an emphasis on clarity of form, and a rejection of the artist's individual emotional imprint, bearing the mark of Concrete Art's influence. Through this development and many others, including the emergence of North-American Minimalism in the early 1960s, the influence of Concrete Art resonates through the subsequent development of postmodern art.

Useful Resources on Concrete Art

- Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and ScotlandOur PickBy Greg Thomas (He is also the writer of this The Art Story page)

- After ConstructivismOur PickBy Brandon Taylor (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2014)

- The Tradition of ConstructivismOur PickBy Stephen Bann (ed.) (New York: Viking, 1974)

- De StijlBy Paul Overy (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991)

- Max Bill: Endless RibbonsBy Jacob Bill (ed.) (Salenstein: Benteli Verlag, 1999)

- Richard Paul Lohse: Colour Becomes FormBy Norbert Lynton (London: Annely Juda, 1997)

- Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820-1980By Dawn Ades (ed.) (London: South Bank, 1989)

- Tomás Maldonado in Conversation with María Amalia GarcíaBy María Amalia García et al (eds.) (New York: Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, 2011)

- Ulm Design: The Morality of ObjectsOur PickBy Herbert Lindinger (ed.) (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1990)

- Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of ArtBy Cornelia H. Butler et al. (eds.) (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014)

- An Anthology of Concrete PoetryBy Emmett Williams (ed.) (New York: Something Else, 2013 [reprint of 1968 original])