Summary of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Kahnweiler is recognized as one of the most important art dealers of the twentieth century. While still in his early twenties, he had spotted the potential in a new generation of artists - the likes of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck and Kees van Dongen - all of whom he represented through his famous Galerie Kahnweiler. Though he also dealt in Fauvist works, he would quickly emerge as the principle dealer in (and intellectual backer of) Cubism. But it was perhaps his long (and at times fractious) association with Picasso that confirmed him his place in the mythology of European modernism. As a German Jew living in Paris in the first half of the century, he was driven out of the French capital during both World Wars. But the exile didn't stop him, as he found the time to write Der Weg zum Kubismus (The Rise of Cubism), a book that gave the world the blueprint for Cubist theory and practice and which remains a seminal text in the history of modern art to this day.

Accomplishments

- Galerie Kahnweiler ranks as one of the most important galleries in art history. Possessed of an imposing self-belief and savvy business acumen, Kahnweiler confronted the prejudices of the Parisian art establishment by creating an unique creative environment that allowed some of the greatest artists of the early twentieth century to rise up and dominate the burgeoning avant-garde scene.

- Pablo Picasso was the first superstar artist of the new millennium and the artist owed much of his success to Kahnweiler. It was the German who saw the potential for Picasso's seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and it was through Kahnweiler, and his sense for the power of promotion and publicity, that the Spaniard became the artist of choice amongst the most progressive collectors.

- Kahnweiler's influence extended beyond France. Indeed, he formed an international network of dealers through whom he was able to "introduce" his artists to new audiences in Europe and America. In a century where the hub of the art world shifted between two capitals, one might say that Kahnweiler was as intrinsic to the international success of the Parisian avant-garde as Clement Greenberg would be to the success of the New York avant-garde.

- Like Greenberg (who thirty years later convinced the world of the value of Abstract Expressionism), Kahnweiler proved to be a formidable and persuasive writer and theoretician. Through his book Der Weg zum Kubismus (not to mention various articles) he was able to put into words how the radical new art of Cubism offered the open-minded viewer a brand new way of looking at the world.

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Important Artists and Artworks

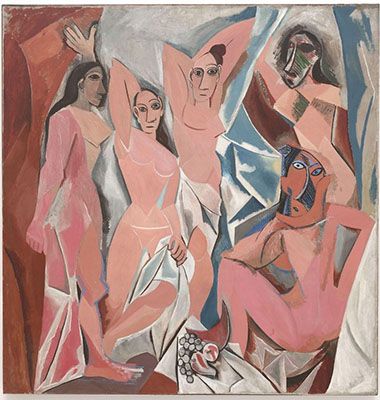

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907)

This proto-Cubist work by Picasso - destined to become one of the most iconic works in the history of world art - depicts five prostitutes on the Carrer d'Avinyó in Barcelona. Most of the figures engage the gaze of the viewer in a direct manner and this, coupled with the artist's general preference for disjointed representation, amounted to a flagrant affront to the conventions of the female nude. Indeed, the women, described by Kahnweiler as "rigid, like mannequins", are imposing in their collective stance. Reflecting Picasso's interest in primitivism, meanwhile, the facial features of the two figures to the right are modelled, not on Western ideals of female beauty, but rather on African masks. The flat, two-dimensional space the women inhabit is similarly angular with an overall effect that marked a truly radical move away from traditional European paintings.

Kahnweiler visited Picasso's studio where he became mesmerized by Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (as it was named later). Though he had been reluctant to sell, Picasso, who was still an unknown artist at the time, and who had become dispirited by the negative responses to the work, was won over by the 23-year-old German's genuine enthusiasm for his painting. Kahnweiler remarked later that something "admirable, extraordinary, inconceivable had occurred" between the two men, and his positive response, coupled with his immediate decision to purchase the painting, proved a turning point in the career of a newly galvanised artist. Kahnweiler saw this painting as the birth of Cubism, writing "this is the first upsurge, a desperate titanic clash with all of the problems at once".

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910)

Keen to support his star artist in his Cubist experiments, Kahnweiler sat for this portrait no less than 30 times. Although working in a traditional idiom - a seated portrait of the artist's dealer - Picasso was not interested in literal representations. He represented his sitter through a series of angular shapes and shifting surfaces which combine to create only an impression of the subject. The planes convey multiple viewpoints, bringing into view Kahnweiler's face and hands via use of lighter shading while other details are discernible amidst the cutting lines and edges of the shapes: Kahnweiler's watch chain (which could be an allusion from Picasso to his dealer's obsession with punctuality), and the waves of his hair, for example. The art critic Jonathan Jones observed that Kahnweiler "haunts [the painting] like a shadow of himself, a nuclear ghost imprinted in space [...] It is not a picture of him. And yet he is fully there, his identity glimpsed with a strange warm intimacy through the shattered glass of the modernist age".

Picasso's contract gave him the financial security he needed to develop his style freely; a decision the Spaniard acknowledged when he observed: "what would have become of us if Kahnweiler hadn't had a business sense?". Indeed, despite their combustible personalities, the two men made a formidable team. As Philip Hook said of Kahnweiler, "in the end, his life and career was justified by his unlikely relationship with Picasso". This portrait was one of the many paintings "sold off" in the notorious Hôtel Drouot auctions in Paris in June 1921 and was purchased by the Swedish expressionist painter Isaac Grünewald before eventually finding its way into the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Village (c.1912)

Considered one of the principal figures in the Fauvist movement, Village is typical of Vlaminck's pre-war period when the artist sought to capture mood and atmosphere over realistic picture detail. He achieved this through the use of heavy brushwork and a distinctively bold palette. In this particular painting, Vlaminck's use of thick dabs of color in place of individual leaves on the tree in the left foreground mirror the wide strokes of the clouds in the sky, thereby creating a sense of movement and stormy foreboding.

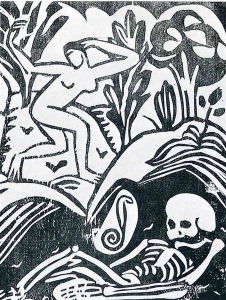

Vlaminck met fellow painter André Derain on a train to Paris in the early 1900s and the two forged a lifelong friendship, even renting studio space together at the start of their careers. Derain had been one of the first artists to sign an exclusive contract with Kahnweiler in 1912, and Vlaminck followed suit in 1913. Kahnweiler influenced both artists in encouraging them to explore the medium of woodcuts and African art. Despite his close relationship with the art dealer, however, Vlaminck was staunchly resentful of Cubism (and particularly Picasso) and remained steadfast in his commitment to the more expressive Fauvist style. Unlike Picasso, Vlaminck was loyal to Kahnweiler during the German's forced exile and publicly protested the Hôtel Drouot sales of his collection following the First World War.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1912)

In this painting Gris depicts his friend and colleague Pablo Picasso. He experimented in the style that became known as Analytic Cubism which he had been practicing since his move to Paris (from Madrid) in 1906. Picasso's face is shown from multiple viewpoints and Gris used various planes and simple shapes to create an organized yet fractured overall view of his sitter. His choice of colors is also simple: here he opted for muted blues and browns, with smaller bursts of brighter colors in the palette Picasso is holding in his left hand. The colors are rendered through the use of diagonal shading, which gives a uniform finish to the work, creating an almost crystalline structure that was typical of Gris's style at this time.

This portrait was the first painting that Gris exhibited publicly after it was chosen for inclusion in the 28th exposition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris in 1912. His choice of subject matter for his debut is telling and demonstrates his respect for Picasso as an artist at the forefront of Cubism. Having moved to Paris six years previously, Gris moved in similar circles to Picasso and befriended many other artists who were on Kahnweiler's roster, such as Georges Braques, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Fernand Léger. Following his debut at the exposition, Gris too signed an exclusive contract with the dealer, and this painting joined many others in Kahnweiler's expanding Cubist repository. But as with so many canonical pre-war works belonging to Kahnweiler, Gris's portrait was auctioned-off at the 1921 Hôtel Drouot sale in Paris. The painting would eventually come back into Kahnweiler's hands at the Galerie Louise Leiris in the 1940s.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Bottle of Rum (1914)

This work is typical of Braque's artistic output in the early-to-mid-1910s. He took the traditional artistic genre of the still life and used in to experiment with geometry and multiple perspectives. Through his shifting use of spots and patterns, the artist creates the impression of a collage built up of layers of paper, when in fact the work is oil paint on canvas. The label denoting the bottle of rum is scattered throughout the painting, as are the curves of the bottle itself. Upon seeing this work at Kahnweiler's gallery, the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles, referred to it with incredulity: a "cubic oddit[y]" that "reduced everything [...] to geometric schemas".

In the years preceding this work, Braque had worked closely with fellow Kahnweiler artist Picasso. Indeed, it was Kahnweiler who introduced the two men who then embark on a seven year relationship founded on a tight friendship and a bitter rivalry (Picasso said of this period that "Almost every evening, either I went to Braque's studio or Braque came to mine. Each of us had to see what the other had done during the day"). Though the men would go their separate ways with the onset of war, they enjoyed a period of extraordinarily productive collaboration that is unequalled in the history of modern art. As with Picasso, it was Kahnweiler's faith in his artists and the financial umbrella he offered them that allowed Braque to experiment with form and texture. This painting was one of the works in Kahnweiler's collection that was seized and sold in the post war auction of his seized assets (as seen in the lot number '19' in the lower left corner of the canvas).

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Le Fumeur (The Smoker) (1914)

In this painting, Léger uses tubular forms to depict a smoker, leaning left, in a three-quarter view. The side of the figure's face is rendered in a solid black curved form, with a rod-shaped red pipe protruding from his mouth. The use of white curved forms, this time with less opaque texture, drifting upwards from the red pipe denote the fumes of smoke. The figure appears to sit at a small table in the lower left foreground, with large square and rectangular planes of yellow in the background. The Smoker was a character Léger returned to in many paintings as he explored the themes of modern urban life. This style is typical of the artist's increasingly abstract paintings at this time, using simple forms and bold colour to create what Guillaume Apollinaire described as "cylindrical painting".

Léger proved to be one of Kahnweiler's most dedicated and loyal artists. He signed an exclusive three-year contract with the dealer in October 1913 in which Kahnweiler agreed to buy all of Léger's oil paintings. Upon returning to Paris in 1920 following his exile, Kahnweiler found continued support in Léger, who agreed to sell part of his output through his new Galerie Simon. During the difficult year of 1921, in which Kahnweiler had to endure the sale of his pre-war collection, Léger supported the dealer by offering him first refusal on all new works. Their relationship went beyond the professional, as evidenced in a friendship that saw them vacation together with their wives in August 1922 in Germany and Austria. Much to the dealer's chagrin, this particular painting was sold in the first Hôtel Drouot sale in June 1921 for the price of 1000 francs.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Biography of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Childhood and Education

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was born Heinrich Kahnweiler in 1884. His family had relocated to the city of Mannheim, in the region of Baden, from the much smaller town of Rockenhausen in the Rhineland-Palatinate province.

Kahnweiler enjoyed a comfortable childhood and received an excellent education at a local German Gymnasium. His early ambition to become a musical composer was short-lived, but led circuitously to his career as an art dealer. As he recalled, "I think the same impulse was behind [being a musician] that made me become an art dealer: an awareness that I was not a creator but rather a go-between, in a comparatively noble sense of the word, since I was not a composer myself". Although banking was the Kahnweiler trade, the family shared a keen interest in art (one of Kahnweiler's uncles, a stockbroker based in London, was himself a collector of traditional English works of art). On completion of his education, Kahnweiler turned down the opportunity to work for his family's business and chose instead to move to Paris - the center of the art world - at the beginning of the twentieth century.

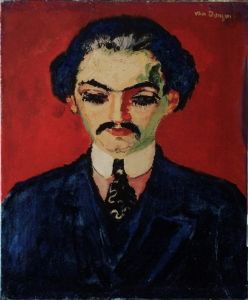

Early Years

In May 1907, the 23-year-old Kahnweiler used a small family inheritance to set up his first art gallery in Paris: Galerie Kahnweiler at 28 rue Vignon. The gallery was only 4 by 4 meters and was something of a financial gamble given that Kahnweiler had chosen to specialize in the challenging new art of the French avant-garde. The gallery enjoyed a busy first year, displaying works by Pierre Girieud and Francesco Durrio (October 1907), Kees van Dongen (March 1908), Charles Camoin (April 1908), and Georges Braque (November 1908). Kahnweiler chose to promote artists whose work he believed in; artists who did not yet have dealer representation, and who were not already on the radar of other collectors. Indeed, choosing to stake his fledging gallery on non-established artists was a brave move; as was his practice of making exclusive contracts with artists to buy all their works. Kahnweiler also believed that he could only be a successful art dealer if he retained exclusive rights to an artist's entire production.

Kahnweiler did not believe in bargaining either; his view was that any decision to display a work of art, or to take on a given artist, should be endorsement enough to recommend it to buyers. The writer Henri-Pierre Roché, and one of Kahnweiler's best clients, remembered his visits to Galerie Kahnweiler as being his first experience of Cubist works and detailed the dealer's unwavering belief in this new movement: "In the beginning of Cubism, Kahnweiler in his small shop introduced me to Cubist Picassos and Braques without saying a word. He introduced me, and his manner said it all. He had the simple authority of someone who announces. For him, Cubism, newly created, was already a classic".

As well as accumulating a roster of up-and-coming artists, Kahnweiler's pre-war years were spent cultivating a client base of international collectors. His clients included the French collector Roger Dutilleul, the prolific Russian art collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, and the Paris-based American collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein. He was also a natural networker, establishing close working relationships with other dealers across Europe and America (including Alfred Flechtheim in Düsseldorf and Berlin, Francis Gerard Prange of the Grafton Gallery in London, Gottfried Tanner of The Moderne Galerie in Zurich, and Michael Brenner and Robert J. Coady of The Washington Square Gallery in New York).

Kahnweiler's serious approach to art can also be seen in his publishing efforts, a pursuit which he would return to throughout his life. He read widely on art history and theory, and spent his free time visiting the museums and galleries of Paris. On journeys abroad, he used his time to contemplate the contemporary art scene on markets outside of France. He also edited books which featured illustrations by artists he represented, such as Guillaume Apollinaire's 1909 debut L'Enchanteur pourrissant, illustrated with woodcuts by André Derain.

As Kahnweiler's reputation grew he was able to attract more artists under his exclusive contract policy. Artists contracted to him were not obliged to produce a prescribed number of works. His ethos was that his exclusive agreements would allow "the painter [to] work without financial concerns" and that once you tell an artist "he has to produce a certain number of canvases, then everything is over". This elastic arrangement appealed to many artists and resulted in exclusive contracts with Picasso (signed in December 1910); Braque (signed in November 1912); Derain (signed in December 1912); Gris (signed in February 1913); de Vlaminck (signed in July 1913); and Léger (signed in October 1913). The acquisition of these names made Kahnweiler the biggest and most formidable dealer in avant-garde art during the 1910s.

Kahnweiler's most successful, and sustained, success was reached through his association with Picasso. Following the harsh reception of Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), it showed daring and self-belief from the artist to continue experimenting with dispersed forms and fragmented modes of representation. However, with the full backing of Kahnweiler, the Spaniard was destined to become the first celebrity artists of the twentieth century. Before being taken under Kahnweiler's wing, Picasso was selling works directly from his studio at the price of 50 francs per drawing. Under the German's guidance, this rate soon doubled to 100 francs for drawings and 3000 francs for paintings, and by March 1913, Kahnweiler had made Picasso a very wealthy young man, paying him 27,250 francs for 26 paintings, 22 gouaches, and 50 drawings. By the end of the year, Kahnweiler had sold (much to Picasso's delight) additional works bringing in a further 24,150 francs. Part of Picasso's rise can be attributed to his dealer's canny control of publicity which saw him cultivate an exclusive clientele for the Spaniard's works. As Kahnweiler's biographer Pierre Assouline states, the dealer was "looking to the future and trying to develop a handful of courageous collectors who would stand apart from the crowd". Additionally, Picasso and Kahnweiler embraced both those who loved and hated the artist's work realizing that polarized opinions generated a discourse about the works.

Through his no-nonsense approach, and his hardnosed business acumen, Kahnweiler was able to "contain" the erratic personalities of many of his artists; not least the flamboyant and fiery Picasso. He was by all accounts a serious man. The German art dealer Heinz Berggruen (who did business with Kahnweiler after the Second World War) remembered him as being akin to a "Prussian schoolmaster" who was too "disciplined to enjoy extremes", while the international art dealer Philip Hook referred to Kahnweiler as "grim, single-minded [...] opinionated, fastidious and not blessed with much of a sense of humor".

In expanding his business empire, Kahnweiler brought together a network of global dealers and loaned his personal stock to galleries outside of France. Soon his cadre of artists featured regularly at galleries across his home country of Germany (in Frankfurt, Cologne, and Munich) as well as in Budapest and St Petersburg. He also recognized the strength of group shows and contributed Cubist works to two Post-Impressionist shows in London in 1910 and 1912, and to the first Armory Show in New York in 1913. Capitalizing especially upon Cubism's successes at the Armory Show, Kahnweiler set up an agreement with the Washington Square Gallery in New York which provided him with a permanent outlet on the American art market. According to Philip Hook, Kahnweiler had become the Cubist movement's "high priest".

Mature Period

In the lead up to the outbreak of World War One, Kahnweiler was seen by many in the art establishment as a negative influence on French painting. Cubism in particular was perceived as difficult to understand and an affront to "quality" French art. Meanwhile, Kahnweiler, who until now had refused to accept the real possibility that France and Germany could possibly go to war - and having had not yet applied for French citizenship (he did so after the war) - found himself an "official" enemy of his host nation. The German's gallery and the artworks were duly seized by the state and Kahnweiler and his family were forced into exile in Bern, Switzerland. It was in Bern that Kahnweiler (who would also publish articles in the German art journals Das Kunstblatt, Die Weissen Blätter and Der Cicerone) completed his book: Der Weg zum Kubismus (The Rise of Cubism). Completed in 1916 (though not published until 1920) the volume remains a seminal text in the history of the art movement. It was in this source that Kahnweiler made the important distinction between the movement's two most important phases: Analytic and Synthetic Cubism.

Upon his return to Paris in 1919, Kahnweiler found a very different city to the one he had left behind. Having made an unsuccessful attempt to retrieve his confiscated property from the government, he had to endure the ignominy of a public sale of 800 of his paintings at four auctions (held at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris in June and November 1921, July 1922 and May1923). Key works by Braque, Gris, and Picasso were all sold off at low prices. Writing to Derain about the experience, Kahnweiler described the sales as "distasteful" and "ugly", commenting that he had "worked so hard, in good faith, for a worthy cause [...] and then in time of peace to be forced to fight like a madman for the return of what had been acquired not only with my money [...] but with the commitment of my whole existence". The auctions caused furor and rifts within the Parisian art scene. Kahnweiler's previous contemporary and friend Léonce Rosenberg, who had taken on many of his artists during the war, agreed to take the role of "expert" at the auctions, which infuriated Kahnweiler and those artists who remained loyal to him. Braque was so angry at the treatment of Kahnweiler that he physically attacked Rosenberg and had to be restrained by Amédée Ozenfant. As well as the artists, some of Kahnweiler's regular collectors objected to the auctions. Roger Dutilleul, for example, did not buy works from the sales, but did buy papers and archives, which he gifted back to Kahnweiler.

In addition to the loss of his collection and his gallery, Kahnweiler found that several of his artists had moved on by signing contracts with other Parisian dealers. His biggest loss was Picasso, who had fallen out with Kahnweiler over a missed payment of 20,000 francs. Kahnweiler owed Picasso the huge amount before the outbreak of the war but, due to money owed by Shchukin (which never materialized because of the tumultuous political situation in Russia) he had been unable to pay the artist. Kahnweiler wrote to Picasso in an effort to resolve their dispute and to ask for his support against the Hôtel Drouot auctions. Pleading with the artist to consider their long friendship and past successes, he wrote: "Our relationship [...] has not been the ordinary relationship between painter and dealer [...] You surely know that I have only these pictures [...] they are my life. I was there when you needed me". Picasso remained unmoved, however, and did not engage with Kahnweiler until the outstanding amount was finally paid to him in 1923.

Kahnweiler and Picasso's complicated relationship was further aggravated by the artist's decision to sign an exclusive contract with Léonce Rosenberg's brother, Paul, who, alongside his partner Georges Wildenstein, had poached many of Kahnweiler's artists, including Braques in 1922 and Léger in 1927. Like Kahnweiler, Paul Rosenberg shared a strategic vision with Picasso as to how to sell his works, aligning him with nineteenth-century masters rather than the more populist Salon Cubists (of whom Picasso was scornful). The strategy worked, and by 1923 Picasso was the highest-priced living artist. Rosenberg had become heir to his father's (Alexandre) business, and dealt in works by the likes of Monet, Cézanne, Manet and Renoir out of his gallery at 21 rue de la Boétie from 1910. Kahnweiler and Rosenberg were bitter rivals and, like Kahnweiler, Rosenberg offered his artists financial security by using the model of exclusive contracts and by guaranteeing the purchase all finished works. In addition to his role as dealer and financial advisor, however, Rosenberg fostered tight personal relationships with his artists and he and Picasso became close friends. Indeed, Rosenberg and his wife were neighbours to Picasso and his wife Olga Khokhlova for many years, with Picasso even in attendance at the birth of Rosenberg's son.

Kahnweiler and Rosenberg's paths crossed throughout their careers. In a series of conversations with the French journalist Francis Crémieux published under the title Mes galleries et mes peintres (My galleries and my painters), Kahnweiler recalled: "Braque went over completely to Paul Rosenberg, for purely financial reasons [...] Léger too. When Léger came to me one day and told me that Paul Rosenberg was offering him twice as much as I was giving him [...] I said 'I think it is a great mistake to overprice that way' [...] because the depression hit soon afterwards, the sales stopped, and Paul Rosenberg never bought anything from him again". When asked by Crémieux whether a gentlemen's agreement existed among art dealers, Kahnweiler replied: "You're very naïve! No, art dealers have always tried to steal from each other the painters whose paintings were selling well".

Late Period

The final challenge Kahnweiler faced upon his return to Paris was to set up his gallery again, despite new rules that Germans were barred from starting businesses in France. In February 1920, he opened Galerie Simon at 29 rue d'Astorg, named after his friend and business partner André Simon (in order to skirt around the new rules). He started to sign up a new roster of artists, including the sculptor Henri Laurens, but his options were limited by his strict devotion to Cubism. Following the war, artists continued to experiment with form and subject matter, but Kahnweiler rejected new movements such as Expressionism, Futurism, and Surrealism. The art market faced further difficulties in October 1929, when the great financial crash forced Kahnweiler to suspend his artists' contracts.

The Nazi occupation of Paris in the Second World War threatened Kahnweiler with a repeat scenario of the First: this time his possessions and business were threatened because he was Jewish. He avoided the seizure of Galerie Simon by circumventing laws which prevented property ownership by Jews. In 1941, the gallery was purchased by the daughter of his wife Lucie Godon - Louise Leiris - who could own property and business as she was a French Catholic. Kahnweiler and his stepdaughter had collaborated throughout the 1920s and 1930s and Leiris shared his passion for collecting modern art, particularly favoring the work of Braque, Gris, and Picasso. Kahnweiler was able to work together closely with Leiris to sustain his business, whilst living quietly in the rural Limousin region to avoid persecution. Again, he used wartime to return to writing.

Following the Second World War, Kahnweiler's eminence as an art dealer and art historian continued to rise. One positive outcome was the rekindling of his friendship with Picasso, who agreed to an exclusive contract with Kahnweiler again in the late 1940s. This boost, coupled with his instinctive business savvy, saw Kahnweiler's gallery soar into the top 100 French companies for exports in the 1950s. In 1961, Kahnweiler donated his personal collection of art to the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris (a gesture copied by Leiris in 1984). Kahnweiler died peacefully in 1979, aged 94.

The Legacy of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Kahnweiler was a key figure in the history of modern art: he shaped the development of Cubism and was primarily responsible for bringing to the attention of art collectors artists who are now household names, such as Picasso and Braque. His opinions and critical eye were so highly regarded that the French industrialist and collector Roger Dutilleul described him as "more of a teacher than a dealer. In truth I became his disciple".

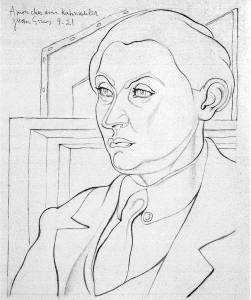

Kahnweiler's dealing method of using exclusive agreements to ensure his artists were financially stable and able to create work at their own pace influenced their creative practices and established a standard of care the industry had not previously seen. The impression he left on his roster of artists can be seen in the large number of portraits they painted of him. Indeed, many of his unique methods of art dealing have now become standard practices in the industry. As Philip Hook describes, "without men such as Kahnweiler, the course of Modernism would have run very differently".

Kahnweiler was also a significant art writer and theorist and even prompted his artists to illustrate books. He was responsible for encouraging writers such as Guillaume Apollinaire, and was, in the opinion of the art historians Yves-Alain Bois and Katharine Streip "a courageous and pioneering editor [...] from early on a champion of the painting that he both loved and sold, a passionate critic whose breadth we have only begun to appreciate". Kahnweiler's book Der Weg zum Kubismus, meanwhile, became a source book for the development of modern art history and it had a profound impact on the epoch-making text, Cubism and Abstract Art (1936), by the art historian, and first director of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr. Indeed, on the occasion of his 80th birthday, a series of interviews were conducted and published in the book Mes galleries et mes peintres (My galleries and my painters), in which leading art historians and artists gathered to celebrate the importance of Kahnweiler's contribution to the world of modern art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Guillaume Apollinaire]() Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire -

![Gertrude Stein]() Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein ![Sergei Shchukin]() Sergei Shchukin

Sergei Shchukin- Henri-Pierre Roché

- Roger Dutilleul

![Paul Rosenberg]() Paul Rosenberg

Paul Rosenberg- Alfred Flechtheim

- Francis Gerard Prange

- Gottfried Tanner

- Michael Brenner

Useful Resources on Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

- An Artful Life: A Biography of D. H. Kahnweiler, 1884-1979Our PickBy Pierre Assouline

- Rogues' Gallery: A History of Art and its DealersOur PickBy Philip Hook

- Kahnweiler: My Galleries and PaintersBy Francis Crémieux, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, John Russell

- Rise of CubismBy Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

- Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century ArtBy Michael C. Fitzgerald

- Dealing Art on Both Sides of the Atlantic, 1860-1940By Lynn Catterson

- Art in France: 1900-1940By Christopher Green