Summary of Ancients

Bejeweled with color, saturated with spiritual fervor, the paintings and engravings of The Ancients are amongst the most rapturous works of Romantic art produced in Britain during the 19th century. The Ancients were a group of young artists based in the south of England who cohered around the inspirational figure of William Blake. Also inspired by classical, Biblical, and Medieval and Renaissance imagery, the group was active for around a decade, meeting mostly at the house of their leading member Samuel Palmer in Shoreham, Kent before the ties of collective creativity gradually loosened. Their influence can be sensed across a wide sweep of Romantic art, from the Pre-Raphaelites to twentieth-century artists such as Graham Sutherland and John Piper.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Ancients formed the first "brotherhood" in modern British art, an indirect influence on the many modernist and avant-garde groupings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Dressing in long, monk-like robes and committing to a shared program of artistic and spiritual labor, their visible adherence to a shared cause was echoed in the pronouncements and artistic output of any number of later movements, although their ideals were rooted in a vision of antiquity rather than an avant-garde grasping at the new.

- The Ancients were one of the most significant movements in British Romantic landscape painting. They rose to prominence at a time when that school was flourishing thanks to artists such as Turner and Constable. But whereas those painters' works precipitated a turn towards Naturalism and Realism in the depiction of the natural world, the spiritual intensity of The Ancients and the influence of Blake gave their work a proto-Expressionist quality of formal and tonal distortion which was entirely without equal.

- Although somewhat neglected in their lifetime, during the twentieth century the work of The Ancients, and particularly Palmer, inspired a new generation of Romantic landscape artists. Painters such as Graham Sutherland, Paul Nash, John Piper, and John Minton, saw in The Ancients' work the same combination of Romantic richness and compositional daring that they were attempting to muster.

Overview of Ancients

The Ancients produced color-filled landscapes and evocative, gothic engravings and etchings. Inspired by William Blake, their work has an almost psychedelic richness and intensity which has appealed to generations of artists and art lovers. However, with the exception of their leader Samuel Palmer, they remain more obscure than the artists they influenced, notably the Pre-Raphaelites and Romantic modernist painters such as Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, and John Piper.

Artworks and Artists of Ancients

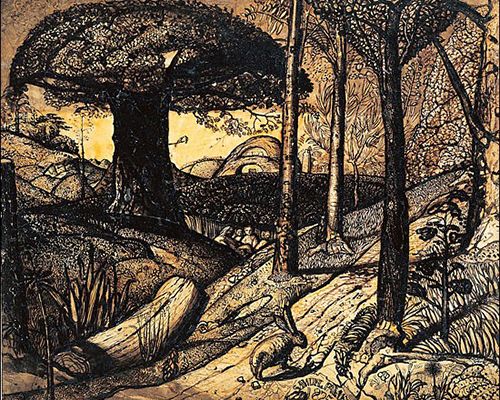

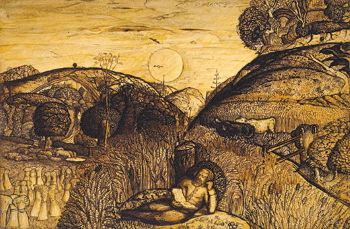

Early Morning (1825)

This rhapsodic early morning scene indicates the ability of the Ancients, particularly Palmer, to produce work at once deeply rooted in antiquity and oddly formally radical. The curvaceous shape of the hare in the foreground and the large, almost topiary-like tree to the left, which immediately draws the eye, is complemented by the gentler rolling forms of the hills. The use of a sepia wash grants the piece the soft atmosphere of early morning light, while the busy depiction of foliage suggests the influence of medieval illuminated texts or tapestries. Although the work is produced in pen and ink, the detailed crosshatching and line-work has much in common with engraving.

Produced early in Palmer's Shoreham phase, Early Morning is one of many works in which a gently receding landscape is populated with varied foliage. The formal arrangement, with the hilly sweep of land drawing the eye towards the horizon, is reminiscent of works of Brueghel's such as The Hunters in the Snow (1565), while Lister suggests the influence of the Renaissance painter Adam Elsheimer's The Realm of Venus, which includes similarly dense foliage. Lister also notes that the odd shape of the tree to the left mirrors those found in medieval illuminated manuscripts . But the formal extravagance of the piece is above all in the spirit of Blake, whose bodies and landscapes often seem to pulsate and distort with spiritual energy. The first plate of "The Echoing Green", from Blake's 1789 version of Songs of Innocence, contains a domelike tree very similar to Palmer's, while the engraving-like quality of Palmer's brushwork is indebted to a method that Blake made his own.

This work is one of Palmer's best-loved, and its influence can be sensed in pieces from the Palmer revivalist era of the early-to-mid-twentieth century. Landscapes by British artists such as Graham Sutherland, John Nash, and John Piper are heavily indebted to Early Morning and similar pieces in their expressionistic shape and color, and in their evocation of the verdant, fecund English countryside.

Pen and dark brown ink with brush in sepia mixed with gum and varnished - Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

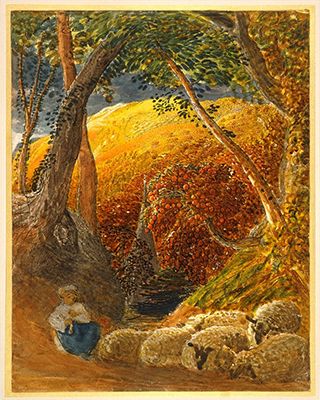

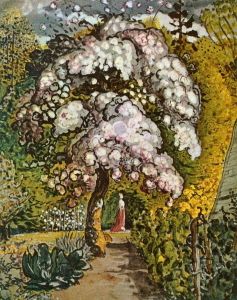

The Magic Apple Tree (ca. 1830)

Palmer's Magic Apple Tree is a masterpiece of The Ancients' Shoreham years, suffused with golden light and animated by a curious quality of motion or liquidity. Nestled in a woodland glade, a shepherdess tends to her flock while playing a pipe, enclosed by the branches of autumn trees on one side and an earth bank on the other. To her right a flock of sheep nestles, the mottling of their wool mirroring that of the orange foliage above. Formally, the piece presents a harmony of enveloping, circular lines, as if an encompassing ring of leaves, light and sky were offering magical protection to the flock. The brushwork is almost proto-Impressionist in its deliberate, painterly quality, while the bold, loose shapes and colors, emotionally expressive rather than naturalistic, predict the approach of Expressionism or Fauvism.

Raymond Lister notes that John Linnell had commissioned Palmer to make some studies from nature in 1828, upon which this work was based. Again, the influence of Blake is clear. Lister suggests that the piping shepherdess evokes the introductory lines of Blake's Songs of Innocence (1789) - "Piping Down the Valleys Wild" - while the strange, globular appearance of Palmer's sheep may be based on the plate for Blake's "The Lamb", from songs of Songs of Innocence, rather than any real-life models . At the same time, the image of the shepherdess is clearly a classical, Arcadian one. Palmer's son A.H. Palmer suggested of this work that "the artist's passionate love for Ceres and Pomona [Roman goddesses of agriculture and fruitful abundance] has led him from the land of plain fact into fairy-land ."

A.H. Palmer goes on to note that "throughout his life [Palmer] reveled in richness and abundant fruitfulness." It is these qualities that have made this painting enduringly popular. As Palmer's biographer Rachel Campbell-Johnston states, "The Magic Apple Tree glows like a great autumn bonfire....... Colour becomes a pure sensual pleasure. These are paintings to glut the appetite ."

Pen and Indian ink, watercolor, in places mixed with a gum-like medium, on paper - Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The Gleaning Field (ca. 1833)

In this late work from the Shoreham period, we find Palmer's color palette darkening and his attention turning - to some extent - towards the realities of country life rather than an exalted Arcadian vision. The gleaners - laborers gathering in the harvested crops - are nonetheless probably the subject of a subtle religious allegory, perhaps reaping the rewards of honest Christian labor or, as the Tate's catalogue notes suggest, working to consolidate the "green and pleasant land" of Blake's "Jerusalem." Around them the dark trees glow gorgeously with evening light, the last slivers of blue visible on the horizon.

Palmer's darkened color palette is partly achieved through the use of a mahogany panel as a base. But it may also reflect the mixing of oil paint with lighter tempera tones, a technique deployed for a number of Palmer's Shoreham pictures. According to A.H. Palmer, "[t]he oil pictures were often begun in tempera...and were wrought not only to a great extent in the technical manner, but also...in the devout spirit of some of the mediaeval pictures ." Lister suggests an affinity with Breughel, particularly his famous gleaning scene The Harvesters (1865 ).

The Tate's catalogue notes on The Gleaning Field suggest that this image of pastoral arcadia "contrasted with the harsher contemporary reality of change and social unrest in the countryside ." At the same time, the encroaching gloom of Palmer's image might itself be read as a kind of eulogy to a vision of rural life which was already fading. By 1833, visits from the other Ancients to Shoreham were becoming less frequent. Two years later Palmer himself would return to London in straitened circumstances. Nonetheless, this image stands out as of the most captivating products of his time in Kent.

Tempera on mahogany panel - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1828)

Few works better evoke the debt of The Ancients to William Blake that this lush tempera work of George Richmond's, depicting a scene from the life of Jesus. In the episode recreated, from The Gospel of John, Jesus meets a Samaritan woman at a well and asks her for a drink, before going on to proclaim: "Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty. The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life." Illustrations of Biblical scenes were common in Western art but they assumed a pitch of fervent intensity in Blake's plates and engravings which Richmond emulates here.

The specific influence of Blake can be sensed in the posture of the female subject, which, Lister states, is close to that of Blake's Bathsheba at the Bath (ca. 1799-1800). The landscape and sky, meanwhile, are reminiscent of various plates from Blake's Illustrations of the Book of Job, while the mixing of Richmond's tempera in preparation for the work involved the same combination of "gums" as Blake's tempera mix. At the same time, the postures of the figure and partial nudity of the female form present a general evocation of an ideal, Classical age of aesthetics.

Richmond's soft yet luminous blue-green color palette, achieved through the use of tempera, as well as the somewhat heavy, fleshy forms of the bodies and tree trunks, and the generally rapturous, allegorical atmosphere, all owe a debt to Blake. But Richmond brings a subtlety of color contrast and physiognomic accuracy which actually surpasses that found in his master's work. This beautiful painting is at once exemplary of The Ancients' output in Shoreham and somewhat unusual in its explicit engagement with Biblical themes, rather than the evocation of God in the landscape.

Tempera and shell gold on Mahogany - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

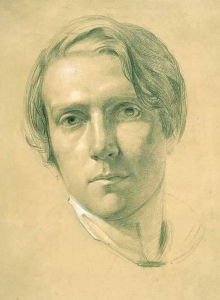

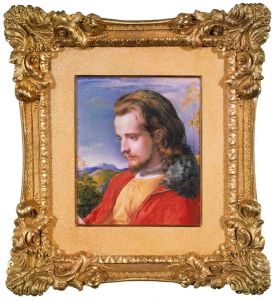

Samuel Palmer (1830)

This delicate portrait, showing Samuel Palmer in the monastic habit and distinctive facial hair he adopted during The Ancients' Shoreham period, indicates Richmond's skill as a portraitist. It also reveals the significance which the group placed on spiritual brotherhood during the 1820s-30s. It would be easy to dismiss the young artists' adoption of, say, foot-length monastic gowns as whimsical or pretentious. But the sensitivity and unselfconscious quality of Palmer's expression in this sketch, and the skill and understatement of Richmond's composition, implies a subject quietly and steadfastly committed to his ideals.

George Richmond was the most skilled portraitist of The Ancients. Indeed, many of the characters of the group and their wider circle, including Richmond himself, are known to us primarily through the likenesses he produced. After his time with The Ancients Richmond became a prolific portraitist, counting politicians, royals, nobles, and the cultural elite of Victorian Britain amongst his sitters. In his own lifetime, Richmond probably seemed to have become the most conventionally successful of the Shoreham brethren.

For that circle itself, the kind of outlandish dress captured in Richmond's sketch was an outward marker of their inward rejection of modern materialistic culture, while also showing the influence they drew from the German Nazarene group. Campbell-Johnston notes that as a young man, Palmer "came increasingly to detest to affectations of fashion.... In Shoreham, he began to adopt to sort of biblical look which the Nazarenes had favoured." In artworks such as Richmond's sketch, "an idealised 'Ancient' emerges who, with his clipped beard and shoulder-brushing locks, serene downcast gaze and long antique robes, looks pronouncedly Christ-like." Campbell-Johnston suggests that Palmer may have served as the model for Christ in Richmond's Christ and the Woman of Samaria .

Graphite on paper - Yale Center for British Art

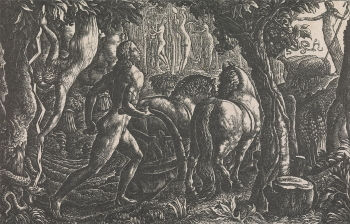

The Chamber Idyll (1831)

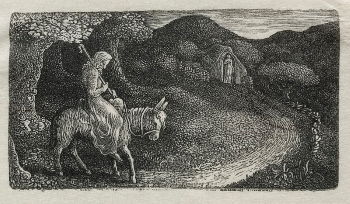

During the late 1820s and early 1830s, Edward Calvert produced a series of beautiful woodblock prints, most of which were only recognized as significant works of 19th century Romanticism when they were reproduced after his death in a memoir by his son. This work, often called Calvert's "masterpiece," was the last and most stunning of them, executed with amazing technical dexterity given that Calvert had only taken up wood engraving four years previously . An image of a honeymoon chamber, this evocation of the moment prior to sexual consummation has classical, Christian, and Blakean connotations, although the central figures are also recognizably 19th-century in aspects of their appearance. In short, the composition is utterly original in style and atmosphere. The work preempts the gothic Romanticism of the Pre-Raphaelites by several decades.

Calvert had begun to practice wood engraving during the Shoreham years, seeing it, according to his son's memoir, as "th[e] most beautiful of all representative arts ." Lister notes that the male and female figures, while wearing contemporary hairstyles, may be based on classical images of Apollo and Aphrodite. The Blakean influence remains evident in the use of an enclosure or frame for the scene, familiar from tempera paintings such as The Adoration of the Kings (1799). The decision to embrace wood engraving as a craft was also influenced by Blake, who used that medium in his "Designs for Thornton's Virgil," an important series for The Ancients as a whole. Other Calvert engravings of this period, such as The Sheep of His Pasture (ca. 1828) and The Ploughman (1827), are more heavily indebted to Blake, mimicking his subject-matter and figures.

It is a poignant footnote to the story of this work that it was Calvert's last engraving. He never returned to the medium, for reasons which are unclear given his obvious affinity for it. Lister notes that Calvert "spent the rest of his life as a recluse, drawing and painting," while devoting much time to complex theories of music and color. In old age, Calvert was reportedly "a magnificent sight, with a white head and beard, but with a clear, almost youthful complexion and limpid eyes, resembling...a kindly and spiritually youthful sage from the classical world of his dreams".

Wood engraving on paper - Cleveland Museum of Art

The Dell of Comus (ca. 1835)

Francis Oliver Finch was probably the most talented and committed of The Ancients outside the core trio of Palmer, Richmond, and Calvert. In his Dell of Comus, he illustrates a scene from John Milton's 1634 poem "Comus", in which two brothers and a sister become separated during a journey through a dark wood. The sister encounters a magical figure based on the Greek god of revelry Comus, who leads her to his enchanted abode (recreated here), traps her, and tempts her with the pleasures of the flesh (which she virtuously refuses). Although the poem is a paean to chastity and restraint, Finch's dell seems an inviting place, lit by startling flecks of white from the revelers' lanterns, with the characters displaying a classical heroism of posture rather than lurching in drunkenness. Finch was influenced by Neoclassical painters such as Claude Lorrain, who may have had an impact on the compositional style of this work.

The Morgan Library's catalogue notes state that the watercolor was "built up using dark pigments enhanced with gum [...] creating a somber but rich effect ." The white sections were then created by scratching away paint, generating the striking color contrast which is central to the visual impact of the work. Campbell-Johnston notes that Finch had been one of Palmer's earliest artistic companions, meeting him well before the Shoreham years, and had "a natural love of learning" which led him towards the illustration of great poetic works. She adds that by the time The Ancients were founded, Finch had already had success with a set of Romantic paintings inspired by James MacPherson's "Ossian" poems. He had also, like Palmer, exhibited at the Royal Academy while he was still a teenager. Finch was said to have been particularly inspired by the poet Keats's image of "embalmed darkness", from his Ode to a Nightingale (1819), a quality which recreated effectively in the enchanted gloom of this image.

After his Shoreham period, Finch became increasingly influenced by the classical imagery previously emulated by 17th-century painters such as Claude and Nicolas Poussin. Finch also become ever more religiously devout. During the late 1820s, Campbell-Johnston notes, he was the most committed of all The Ancients to Blake's spiritual vision, and later in his life he converted to the strange Christian cult of Swedenborgianism , which placed an emphasis on spiritual communication between the living and the dead (Blake had been a Swedenborgian for many years.) Finch and Palmer remained affectionate associates, however, throughout their lives.

Watercolor - The Morgan Library and Museum, New York

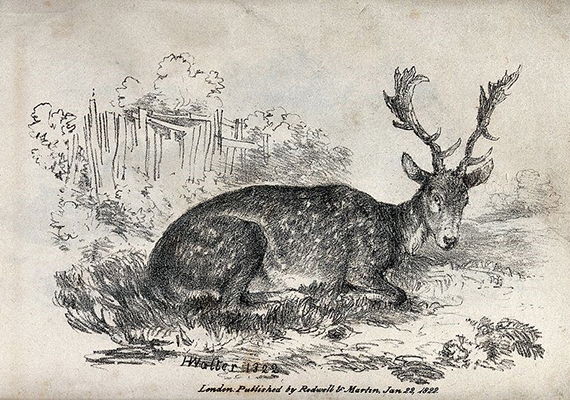

Fallow Deer (1822)

Henry Walter was a talented but somewhat ill-fitting member of the Ancients, primarily remembered for a couple of amusing caricature portraits of Samuel Palmer, which cut against the earnest sincerity of Richmond's and others' likenesses. They suggest that Walter was an unusually lighthearted adherent of the fellowship, but he was also a talented sketcher and painter of animals, as this 1822 illustration shows, with its close attention to the physiognomy of the resting, spotted deer.

Like Finch, Walter was an early creative companion of Palmer's. Rachel Campbell-Johnston notes that "Walter appears to have been included amongst the Ancients purely on the strength of old friendship because his pictures...have nothing to do with the spiritual aesthetic of the group ." Lister notes, however, that "The Ancients had a well-developed sense of humor," citing Walter's caricatures as "manifestations of their lightheartedness ."

In either case, Campbell-Johnston points out that Walter "added gaiety to their gatherings...and, as far as the artists' children were concerned, put his skills as an animal painter to most impressive use, making a wolf mask for a Christmas party which they would always remember for its bright glass eyes, jagged teeth and lolling tongue of red cloth ." After his marriage in the 1830s, Walter's already loose commitment to the group faded, and little is known of his later life except that he settled in Devon.

Chalk lithograph - Wellcome Collections, London

Beginnings and Development

Blake the Interpreter

During the mid-1820s, a group of young male artists gathered around the figure of William Blake, by then in his sixties and living in relative poverty in London (he would die three years later, in 1827). These artists shared Blake's disdain for industrial and urban modernity, and his belief in the possibility of a new, spiritually infused art of landscape that could evoke an ancient, golden age of pastoral life. The most committed and prodigious of these artists were Samuel Palmer, Edward Calvert, and George Richmond, but they were part of a wider circle also including Francis Oliver Finch, Henry Walter, Frederick Tatham, Welby Sherman, and others. Supporters and fellow travelers included John Giles, a cousin and patron of Palmer's, Tatham's siblings Arthur and Julia - the latter of whom married George Richmond - and the older artist John Linnell, whose introduction of Palmer and Blake in 1824 precipitated the group's emergence. Linnell's daughter Hannah was also a talented artist and became the wife of Samuel Palmer.

Early Lives: Palmer, Richmond, and Calvert

The artists who congregated in Blake's apartment were mostly remarkably young, in some cases still teenagers. Samuel Palmer was born in 1805 in Newington, London, the son of a bookseller father and a mother from a cultured background, whose father had been an amateur author and composer. Palmer's childhood was filled with books, the stock of his father's trade, and wide reading was fundamental to his early intellectual development.

Though a sickly child requiring a nurse, Palmer took long walks in the countryside around London with his father. Palmer described the area between Greenwich Park and Dulwich, then still rural, as "The Gate into the World of Vision ." His mother, meanwhile, encouraged him to copy botanical and architectural drawings. After her death in 1818 he went to study with the drawing master William Wate.

Unlike the majority of the Ancients, Palmer received relatively little formal training, and never attended the Royal Academy. Critic Martin Postle notes his reluctance to undertake laborious copying work, and his belief, confirmed by his encounter with Blake, that it was unnecessary to conform to academic standards. However, Palmer developed creative friendships with several olderother artists that would prove crucial to his development.

Most significantly, at the age of seventeen, he met the painter John Linnell (1792-1882), with whom he would remain companions for the remainder of their lives, although Palmer's biographer Rachel Campbell-Johnston notes that their relationship became increasingly strained after Palmer's marriage to Linnell's daughter. Linnell's Romantic, pastoral scenes rivalled Constable's for price and reputation during the early 19th century and played a key role in guiding Palmer towards the Romantic pastoralism of his maturity. Palmer is quoted as saying: "by the time I had practised for about five years I entirely lost all feeling for art...But it pleased God to send Mr. Linnell as a good angel from Heaven to pluck me from the pit of modern art ." As well as introducing Palmer to Blake, Linnell opened him up to the world of German and Italian Renaissance painting and mural-work, notably the work of Albrecht Dürer, Francesco Traini, Buonamico Buffalmacco and Benozzo Gozzoli. The influence of Renaissance and Late Medieval art would prove crucial to The Ancients as a whole.

George Richmond's early artistic education followed a more traditional course than Palmer's. Born in 1809 in Brompton, then a village outside London, George was the son of a miniaturist and, unlike Palmer - whose professed childhood interest was more in church history than art - was determined from a young age to become a painter.

Richmond was just fifteen when he enrolled in the Royal Academy, where the Professor of Painting and Keeper was the gothic Romantic artist Henry Fuseli, an influence on Blake and Palmer as well as Richmond. A year later, at the age of sixteen, the young artist - like Palmer - became friendly with Linnell, who probably introduced Samuel and George to each other. It was also through Linnell, at his house in north London, that Richmond first met Blake. After that meeting, the teenager reportedly walked back across the fields to Blake's home at Fountain Court, during which time Blake made such an impression on the sixteen-year-old that he determined to follow in the older man's footsteps for life, later recalling that he felt "as though he had been walking with the prophet Isaiah ."

Edward Calvert, the final member of The Ancient's core trio, was the only one born outside London: in 1799, to a soldier in Appledore, Devon. Six years older than Palmer and ten years older than Richmond, Calvert had had the most varied life experience before becoming immersed in art, including a naval career which saw him take part in the Bombardment of Algiers, a British and Dutch mission to free Christian slaves from North Africa in 1816.

Having practiced drawing during his military career, Calvert settled in Plymouth upon his discharge, working under the artist A.B. Johns, who knew J.M Constable and took Calvert to visit him on at least one occasion. Having private wealth, Calvert was able to relocate to London in 1824, where he met Samuel Palmer through his cousin, the stockbroker and Ancients supporter John Giles. Calvert was soon a student at the Royal Academy and had met both Richmond and Blake.

Around this central group coalesced a wider network of young artists, some of them also very talented, though many less committed to the vision of Blake, including the painter Francis Oliver Finch, the sculptor Frederick Tatham, the caricaturist and animal painter Henry Walter, and the mysterious engraver Welby Sherman, of whom little is known, but who reportedly fled abroad in 1836 after swindling Palmer's brother William out of £500. The scene was set for the emergence of the first brotherhood in modern British art - and it was indeed an almost exclusively male group - preempting by several years the similar ethos of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Becoming the Ancients

A significant number of the artists connected to The Ancients were introduced to Blake in London in 1824, and the emergence of the group can be pragmatically dated to that year, although it may only have truly cohered after Samuel Palmer's move to Shoreham, in rural Kent, in 1826.

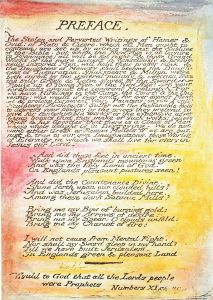

It is not totally clear how the group seized upon their evocative name. Morton D. Paley notes that the coinage is sometimes attributed to the stockbroker and Ancients fellow-traveler Giles, "who constantly used to assert the superiority of the ancients in all things." However, as Paley continues, it is also likely that William Blake was a primary or secondary inspiration. His work is peppered with references to 'the ancient': from the "feet in ancient times" of his preface to Milton (better known as the hymn "Jerusalem") to The Four Zoas, in which "Albion" [Blake's England] is described as "The Ancient Man," and most significantly, the Descriptive Catalogue of illustrations which he produced in 1809, in which the word "ancient" appears thirteen times. "These are amongst many instances," Paley states, "in which Blake uses 'ancient' to suggest a primal state of harmony and power, one that can be recovered through the agency of art ." In 1824, Blake was also producing the engravings to George Cumberland's Outlines from the Ancients, and the younger artists may have seen the plates at Blake's home in Fountain Court.

The term stood for the general principle of the young artists mission: to recuperate or recover a golden age of art located somewhere in the past, connected partly to ancient Greece and Rome, but also to a Biblical, Christian pastoral antiquity, one connected to a vision of the English countryside. The ideal was to be achieved through paintings, etchings and engravings - landscapes primarily, but also portraits and genre pieces - in which a timeless spirit would be manifested. The program was never formally summed up or committed to paper, but is encapsulated by a statement of Blake's from his Descriptive Catalogue: "Painting and Sculpture as it exists in the remains of Antiquity and in the work of more modern genius, is Inspiration, and cannot be surpassed."

The Move to Shoreham

Samuel Palmer's childhood illnesses had accompanied him into adulthood. In 1824 he was suffering with asthma and bronchitis, and reportedly left London on his mother's advice for a restorative holiday. Visiting the village of Shoreham in Kent, he found a warm, verdant setting where, as the reviewer Kathryn Hughes puts it, "the rents were sufficiently low and the locals correspondingly accommodating ." After inheriting £3000 as a result of his grandfather's death in 1825, Palmer decided to use the money to settle permanently in Shoreham in 1826.

The artist first bought a run-down cottage which was affectionately christened "Rat Abbey", in reference to the groups' spiritual aims as well as their rodent co-habitants: as well as, perhaps, the influence of the Nazarenes, a contemporary German artistic group with similar aims, of whom the Ancients were aware. The Nazarenes had settled in an abandoned monastery outside Rome 16 years previously. From 1826 onwards, Shoreham became an equivalent practical and spiritual base for Palmer and his compatriots. Other members of the collective would visit frequently, including Richmond and Calvert, while the engraver Welby Sherman settled nearby. Blake is known to have visited once.

According to the writer Carlos Peacock, life at Rat Abbey was characterized by a "regime of monastic austerity," with a spartan diet and little expendable income . Nonetheless, the art historian William Vaughan describes Shoreham as The Ancients' "'earthly paradise', a rural refuge from the city." He notes the impact that the landscape and culture of the area had on their work: For Palmer the period was one of great imaginative release, during which he developed the primitivizing tendencies that he had previously gained from studying the works of medieval artists and Blake into a unique manner of his own. Richmond painted religious and mythological works of startling primitivism, while Calvert, inspired by woodcuts and engravings of the early Renaissance, produced wood engravings of rustic rituals of arresting sensuality and vigor.

Extracts from Palmer's diary, written during the early days at Shoreham, reveal the extraordinary state of religious fervor in which he worked: At Shoreham, Kent, August 30, 1826. God worked in great love with my spirit last night, giving me a founded hope that I might finish my [painting] Naomi before Bethlehem...That night, when I hoped and sighed to complete the above subject well...I hoped only in God, and determined next morning to attempt working on it in God's strength...Now I go out to draw some hops [flowers of the hop plant] that their fruitful sentiment may be infused in my figures .

The second half of the 1820s was a period of extraordinary productivity, coupled with intense group activities and discussions, long nocturnal walks , and the adoption of monastic or messiah-like dress (as in George Richmond's portrait of Samuel Palmer in "Christ-like garb" [Vaughan] from 1829 ). The group were known by the locals and dourly tolerated, Vaughan notes, although they were sometimes sardonically referred to as "the 'extollagers', a rustic stab at the word 'astrologer '," on account of their eccentricity and otherworldly appearance.

Shortly after Palmer's move to Shoreham, his father sold his book business and joined his son in Kent, renting half of a large house on the banks of the River Darwent. Samuel's nurse and brother also came to live with the family in Shoreham. The Water House, as the older Palmer's lodgings were known, was initially used to house guests who could not be accommodated at Rat Abbey, but in 1828 Samuel left the run-down cottage to join his family in their more comfortable property, remaining there until he left Kent in 1835. It was during this time that he met the artist Hannah Linnell, daughter of his mentor John Linnell, whom he would marry in 1837.

Concepts and Styles

William Blake

Although William Blake had still not achieved commercial success when he encountered The Ancients in the mid-1820s, he was a prophetic, almost God-like figure to the younger group. According to Morton D. Paley, "he was compared by them to a biblical patriarch...; his two rooms in Fountain Court, Strand, were Bunyan's 'House of the Interpreter'" (a reference to a building in John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress in which God's word is revealed ). For Palmer, Blake was "a man without a mask; his aims simple, his path straightforwards, and his words few; so he was free, noble, and happy." Finch described Blake as "a new kind of man, wholly original, and in all things ."

At the root of this admiration for Blake was a respect for his attachment to the natural world, his sense of its visible and tangible saturation with divine force, his scorn for industrial civilization, and his fidelity to his own, unique vision. The Ancients felt this was particularly expressed in Blake's smaller, landscape works, such as his "Designs for Thornton's Virgil" (1821), illustrations to a set of pastoral works by the Roman poet Virgil produced for the schoolmaster Robert Thornton.

The wider influence of Blake is clear in the Ancients' curiously revolutionary approach to form and color during their time in Shoreham. Bodies, hills, and trees appear in exaggerated, rounded or muscular forms, in the style of Blake's rippling physiognomies. So too the rapturously bright color of much of their work, capturing and transforming the magical qualities of light and foliage, reflects the legacy of Blake's luminous prints.

The young acolytes were seemingly less engaged by what Samuel Calvert - paraphrasing his father Edward Calvert - described as "the ungovernable mysticisms of Blake's imagination - the Gothic phantasms of a SPIRITUAL cosmos ." This is presumably a reference to the complex pantheon of imaginary gods and demons with which Blake populated his artistic universe, which jarred with the somewhat less lurid, though still intense Anglican Christianity of his followers. It is also important to note that, while the human character and body played a central role in Blake's pictorial oeuvre, The Ancients were primarily focused on landscapes, in the emerging spirit of 19th century Romanticism - although Richmond certainly became an accomplished portraitist.

Brotherhood

The art historian and authority on The Ancients William Vaughan notes that their emergence "represents the earliest example in Britain of a practice of setting up breakaway groups that became common in avant-garde circles throughout Europe in the nineteenth century." The Ancients thus represent a precursor (often unacknowledged) to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who are more commonly taken to comprise the first "avant-garde" in Britain. Indeed, the Pre-Raphaelite conception of 'brotherhood' owed much to the example of Palmer et al.

As the nineteenth century wore on, groups of idealistic young artists across Europe would increasingly break away from contemporary convention and institutional structures in order to grasp at some idea of "the new." But while The Ancients preempted this cultural shift, they were more interested in reembracing a sense of the past, in which art and spirituality were more closely bound up, and which was unsullied by the encroaching materialism of the Victorian age.

In this sense, The Ancients' concept of brotherhood was religious and - indirectly - political, as well as artistic. The spiritual overtones of their pursuit are reflected in their attempt at a collective living arrangement in Shoreham, somewhat in the style of a medieval abbey or monastery, and by their adoption of shared dress.

However, Vaughan also points out that forming a collective identity, by which "The Ancients" might be recognized as such, was also commercially minded. It was a way of attracting attention, giving their creative output a stamp of identity, and hopefully generating sales. In this respect their mission was a failure, as the group achieved very little commercial success during the decade it spent in Shoreham.

Medieval and Renaissance Art

As the art historian Raymond Lister wrote in 1984, "The Ancients were not uniquely inspired young men who conjured up from their unaided imagination alone an entirely new aesthetic. Their work was based securely on the traditions of Western art...That is one powerful reason when they themselves - especially Palmer and Calvert - continue to influence artists and writers ." This tradition included the art of the Late Medieval and Renaissance eras, in particular the work of Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, Jan van Eyck, and Adam Elsheimer.

In this work The Ancients found, like the Pre-Raphaelites did in the earliest of it, an artistic vision infused with religiosity, uncorrupted by contemporary materialism and individualism, produced in a spirit of creative fraternity and harmony with the natural order of the universe. On the influence of Dürer, Palmer is reported to have said: "Let me remember always, and may I not slumber in the possession of it, Mr. Linnell's injunction (delightful in the performance), 'Look at Albert Dürer'."

As this suggests, John Linnell was particularly important as a conduit for the Ancients' art-historical knowledge. Not only was he a source of expertise but he was also able to introduce them to the collection of Northern European paintings, including many Renaissance works, held by Karl Aders, a German merchant and collector based in London. These included a copy of the Van Eyck brothers' Ghent Altarpiece, with its central panel The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (1420s-32), whose "clarity of detail", "celebration of nature in all its rich detail," and depiction of the "human, natural and spiritual worlds" in harmony was, Paley notes, inspirational to Blake as well as to his young compatriots.

A Christian Arcadia in England

The rich pastoral landscapes of south-east England were central to The Ancients' artistic vision, which is why their relocation to Shoreham was so vital. The group's ideal of a rural Arcadia was, in turn centrally informed by their spirituality. But whereas William Blake's Albion is peopled by the weird deities and demons of his imagination, the Ancients' religiosity was more tethered to Christian tradition.

Despite the heretical strangeness of Blake's religious imagination, Palmer managed to home in on Blake's most conventionally Christian-themed and Biblical works in his early encounters with the older artist's output. As Paley notes, before turning to landscapes, Palmer was "drawn to figure-centered designs on Biblical subjects" under Blake's influence . This would have included Blake's Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab (1795), as well as his Illustrations of the Book of Job (1806-21). Shortly after his first meeting with Blake, Palmer completed a set of sketches on subjects from the Book of Ruth, now lost, which were reportedly heavily influenced by the imagery and formal extravagance of both Blake and Henry Fuseli.

The spiritual essence of these figurative works was carried forwards into the landscapes which Palmer began to produce at Shoreham, and into the work of The Ancients as a whole. You can sense, in early Shoreham works such as Palmer's Coming from Evening Church (1830), the transference of a sensibility grounded in religious and allegorical tableaux into depictions of the contemporary English countryside. It is partly this that gives these landscapes such a strange sense of removal from their subject-matter, as if they were landscapes glimpsed through a veil of ancient enchantment.

Like their mentor Blake, The Ancients were vehemently opposed to the industrial revolution, and to the accompanying mechanization of labor and urbanization which marked the 19th century in Britain. They saw these processes as symptomatic of materialism, a spiritually degrading process by which people became detached from the spiritual essence of the landscape, of human relationships, and of their own characters.

High Tory pastoral

Although the Ancients shared Blake's infatuation with rustic life, they lacked his accompanying egalitarianism, which made him an ally of the downtrodden and a natural supporter of causes such as the French Revolution. The Ancients' political views, by contrast, veered towards a position which Palmer described as "High Tory": belief in a God-given hierarchy within human society mirroring that of the natural world, incorporating clearly separate but harmonious layers such as the aristocracy, church, and peasantry. The point of overlap between this position and Blake's radical left politics was a shared scorn for the new, mercantile worldview of industrial capitalism, which was dislodging the feudal system to which The Ancients clung and promising new forms of oppression to the working masses pitied by Blake.

Some indication of The Ancients' politics is provided by accounts of their stay at Shoreham and the reasons for its eventual end. Palmer's son A.H. Palmer once wrote that, judging from their pictures, "none of the Ancients seemed to know how reaping was done." As this suggests, the young artists had little direct contact with rural laborers, in spite of their eulogization of rural life, and seemingly had little empathy with their working conditions.

In 1830, when farm workers near Shoreham protested against the introduction of threshing machines by burning them along with hayricks and other equipment - a campaign known as the Captain Swing or Swing Riots - Palmer's reaction was furious anger and fear. He denounced the campaign as vicious thuggery in a public 1832 letter, and the events went some way to burst his Romantic vision of life at Shoreham.

Is this sense, it is important to remember that the spiritual vision infused in The Ancients' landscapes is one tied up with a sense of the human world as fixed in a divinely ordained pyramid of privilege. When that pyramid seemed to be under threat of collapse, The Ancients' worldview to some extent disintegrated with it.

International Compatriots

Although brotherhoods of the type that The Ancients formed were unprecedented in Britain at the time, similar groups had already emerged in continental Europe. The best-known were the Barbus or Primitives in France, formed in 1798, and the Brotherhood of St. Luke formed in Germany in 1808, later known as the Nazarenes. For Vaughan, "such associations can be seen as symptomatic of a widespread social and political tendency towards the formation of associations in the wake of the French Revolution. Inspired by the clubs of the Jacobins, such organizations emphasized the replacement of hierarchy with more egalitarian practices ."

In this sense, although The Ancients' vision of collective creativity was undoubtedly inspired, it was not unprecedented. Indeed, given that they were probably aware of The Nazarenes by the time they moved to Shoreham, and also that the German brothers had taken up quarters in an abandoned monastery, The Ancients' collective living arrangement and its monastic overtones might partly have represented a homage to, or mimicry of, the Nazarenes.

Although the formal idiosyncrasy of The Ancients' work sets it apart from Naturalism or Realism, their activities are also tangentially related to the emergence of those schools from the early 19th century, as a distinct outgrowth of the larger Romantic landscape movement. That movement was flourishing in the early 19th century through the influence of Turner and Constable, both of whom, along with John Linnell, were influential on members of the group at different times, helping to instill in them a love of landscape for its own sake.

Later Developments - After Ancients

After Shoreham

By the early 1830s, the Ancients' infatuation with ascetic rural life was waning, and visits from other members of the group to Palmer's house in Shoreham became less frequent. The group's disillusionment with the character of the rural English laborer after the Swing Campaign, exemplified by Palmer's reactionary anger, may have been partly to blame. However, Vaughan suggests that "lack of recognition was probably the primary reason for the artists dispersing", noting that "the Ancients achieved little success during the time they were active as a group ."

Other factors, such as Richmond's increasing focus on portraiture, Calvert's disillusionment with the more formally radical aspects of his youthful work, and Palmer's financial precarity, were all contingent on this underlying lack of commercial and critical appetite for their art. So, in 1835, Palmer moved back to London, to a house in St. John's Wood which he had bought with a second inheritance received in 1832. He began tutoring to supplement his artistic income.

In 1837, after Palmer married Hannah Linnell, he, Richmond, and their wives left on a two-year-long trip to Italy, at which point The Ancients, already geographically and artistically adrift, were effectively dispersed as a group. However, this break was not accompanied by the acrimony that sometimes marks the disintegration of intense artistic communities. Vaughan points out that "many [Ancients] remained close friends and continued to meet regularly, with the majority looking back on their association as the most inspirational artistic episode of their lives."

In his mature years, Palmer began to produce more formally conventional, less mystical works, partly from a desire to make a commercial success of his art, which was never fully realized. Nonetheless, he produced fine late works such as his watercolor illustrations for Milton's poems "L'Allegro" and Il Penseroso" (1864-81) and was admired by the younger artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Richmond established himself as a portraitist, painting members of the nobility as well as authors such as Charlotte Brontë, while Calvert's work began to show a marked classical influence following a visit to Greece in 1844. So too did the later work of other members of the Ancients such as Francis Oliver Finch. All of the most important erstwhile members of the Ancients, however, would look back on the hallowed days at Shoreham as the most creatively rich period of their lives.

Legacy

The Ancients, with the exception of Samuel Palmer, remain a more obscure group of artists than their sometime master William Blake. But a love of their magical, light-filled landscapes and historical tableaux has gradually blossomed across the twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries.

During their lifetimes, and certainly during the active years of the brotherhood, most of the group achieved little success. For several decades after the deaths of the key members (Samuel Palmer in 1881, Edward Calvert in 1883, and George Richmond in 1896) interest in The Ancients remained subdued, although Palmer's connection to the Pre-Raphaelites ensured a thread of influence. The Ancients' impact on the late Romanticism of the Fin de siècle period can also be sensed. The great Irish poet of that era, W.B. Yeats, was inspired by The Ancients' imagery in several of his works, such as "Under Ben Bulben" and "The Phases of the Moon."

A gradual gathering of appreciation followed an exhibition of Ancients' work at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1926. This was partly contingent on the increasing popularity of Blake at this time, as the younger artists were still largely considered his acolytes. Interest became more pronounced in creative circles during the early-to-mid twentieth century, during the "New Romantic" period in British art and literature. You can sense The Ancients' influence in works such as Graham Sutherland's Hangar Hill (1929), John Minton's illustrations for H.E. Bates's The Country Heart (1949), and the wood engravings of Reynolds Stone. Other artists influenced by Palmer and The Ancients include John Piper, the Nash brothers, and the composer Benjamin Britten, who, according to the critic Tim Barringer, requested that Palmer's Cornfield by Moonlight with the Evening Star (1830) be reproduced on the cover of his 1944 score for Serenade.

A 1956-57 exhibition organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain set the stage for the group's wider reception across the late-twentieth century. A series of US and UK books and exhibitions buoyed The Ancients' status, though it remained dominated by the figure of Palmer, and very limited within mainland Europe. In the early twenty-first century, exhibitions such as the 2005 Palmer retrospective at the British Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and books such as Rachel Campbell Johnson's Mysterious Wisdom: The Life and Work of Samuel Palmer (2011) have emphasized Palmer's status as that of a great English painter and sketcher of the 19th century, to be placed alongside Blake, while also emphasizing the creative richness of The Ancients' collective vision.

Useful Resources on Ancients

- Mysterious Wisdom: The Life and Work of Samuel PalmerOur PickBy Rachel Campbell-Johnston

- Samuel Palmer: The Visionary YearsBy Geoffrey Grigson

- Samuel Palmer and 'The Ancients'By Raymond Lister

- A Memoir of Samuel PalmerOur PickBy Samuel Palmer, A.H. Palmer, and F.G. Stephens

- Samuel Palmer RevisitedBy Simon Shaw-Miller and Sam Smiles

- Samuel Palmer: Shadows on the WallOur PickBy William Vaughan

- Samuel Palmer 1805-1881: Vision and LandscapeOur PickBy William Vaughan and Elizabeth E. Barker

- Samuel PalmerBy Timothy Wilcox

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI