Summary of William Blake

Though he is perhaps still better-known as a poet than an artist, in many ways William Blake's life and work provide the template for our contemporary understanding of what a modern artist is and does. Overlooked by his peers, and sidelined by the academic institutions of his day, his work was championed by a small, zealous group of supporters. His lack of commercial success meant that Blake lived his life in relative poverty, a life in thrall to a highly individual, sometimes iconoclastic, imaginative vision. Through his prints, paintings, and poems, Blake constructed a mythical universe of an intricacy and depth to match Dante's Divine Comedy, but which, liked Dante's, bore the imprint of contemporary culture and politics. When Blake died, in a small house in London in 1827, he was poor and somewhat anonymous; today, we can recognize him as a prototype for the avant-garde artists of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whose creative spirit stands at odds with the prevailing mood of their culture.

Accomplishments

- Blake was perhaps the quintessential Romantic artist. Like his peers in the world of Romantic literature - Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelly - Blake stressed the primacy of individual imagination and inspiration to the creative process, rejecting the Neoclassical emphasis on formal precision which had defined much 18th-century painting and poetry. Above all else, Blake scorned the contemporary culture of Enlightenment and industrialization, which stood for a mechanization and intellectual reductivism which he deplored. Blake felt that imaginative insight was the only way to cast off the veil thrown over reality by rational thought, claiming that "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite."

- Blake is unique amongst the artists of his day, and rare amongst artists of any era, in his integration of writing and painting into a single creative process, and in his use of innovative production techniques to combine image and text in single compositions. Celebrated for his visual output, Blake is also recognized as one of the most radical poets of the early Romantic period, combining a highly wrought, Miltonic style with grand, Gothic themes. Moreover, through original techniques such as his "illuminated printing" Blake was able to adapt his craft to meet the demands of his creativity.

- Blake's spiritual vision was central to his creativity, and was crucially and uniquely informed by a complex, imaginative pantheon of his own making, populated by deities such as Urizen, Los, Enitharmion, and Orc. Grand allegorical narratives illustrated with Blake's own designs, were played out in this universe, which might seem to have existed in a space apart from reality. However, in his epic poem sequences, Blake imagined the fate of the human world, in the era of the French and American Revolutions, as hinging on these sequences, determined by the battles between reason and imagination, lust and piety, order and revolution, which his protagonists represented.

Important Art by William Blake

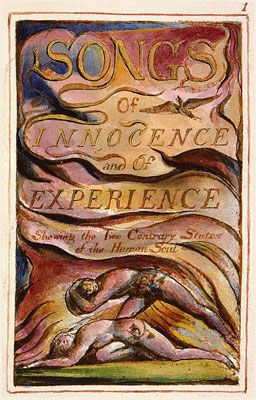

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Songs of Innocence and Experience, a collection of poems written and illustrated by Blake, demonstrates his equal mastery of poetry and art. Blake printed the collection himself, using an innovative technique which he called 'illuminated printing: first, printing plates were produced by adding text and image - back-to-front, and simultaneously - to copper sheets, using an ink impervious to the nitric acid which was then used to erode the spaces between the lines. After an initial printing, detail was added to individual editions of the book using watercolors. Prone as he was to visions, Blake claimed that this method had been suggested to him by the spirit of his dead brother, Robert. Songs of Innocence was initially published on its own in 1789. Its partner-work, Songs of Experience, followed in 1794 in the wake of the French Revolution, the more worldly and troubling themes of this second volume reflecting Blake's increasing engagement with the politically turbulent era.

The cover of Songs of Innocence and Experience includes the subtitle "The Two Contrary States of the Human Soul," a reference to the opposing essences which Blake took to animate the universe, depicted throughout the collection through a range of contrasting images and tropes. Beneath this caption are a man and woman, presumably Adam and Eve, whose bodies mirror each other, but are connected by Adam's leg, another indication of the dualities at work in the book. The use of vibrant color, and the intensity and fluidity of Blake's lines, creates a sense of drama complemented by the figures' anguished appearance. At the same time, the dance-like orientation of their bodies creates an almost childlike sense of play, which jars with the lofty nature of the project.

Unappreciated during his lifetime, Blake's illuminated books are now ranked amongst the greatest achievements of Romantic art. They indicate his artisanal approach to his craft - influential on the 'cottage industries' of subsequent printer-poets such as William Morris - and his hatred of the printing press and mechanization in general. The question underlying this collection is how a benevolent God could allow space for both good and evil - or rather, innocence and experience - in the universe, these two necessary and opposing forces summed up by the contrasting images of the lamb and "the tyger", the subjects of the two best-known poems in the sequence. The influence of Blake's "tyger", in particular, its eyes "burning bright,/ In the forests of the night", echoes down through literary and artistic history, seeping into popular culture in a myriad of ways.

Pen and watercolor - Various editions

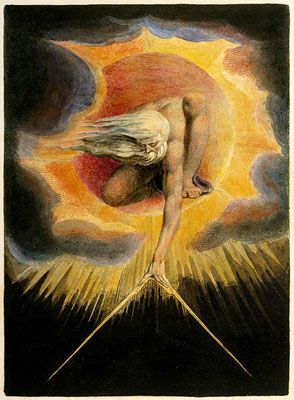

The Ancient of Days

The Ancient of Days, one of Blake's most recognizable works, portrays a bearded, godlike figure kneeling on a flaming disk, measuring out a dark void with a golden compass. This figure is Urizen, a fictional deity invented by Blake who forms parts of the artist's complex mythology, embodying the spirit of reason and law: two concepts with a very vexed position in Blake's moral universe. Urizen features as a character in several of Blake's illuminated long poems, including Europe: A Prophecy, for which this illustration was created. There, and here, Urizen is a repressive force, impeding the positive power of imagination. This piece can thus be read in light of a famous line from another of Blake's long works, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction."

In many ways, Blake is the exemplar for our modern conception of the Romantic artist. He prized imagination above all else, describing it not as "a state" but as the essence of "human existence itself." Thus, as The Ancient of Days implies, he disdained attempts to rationally curtail or control the power of imagination. This is also clear from the annotated version of Sir Joshua Reynold's Discourses on Art (1769-91) which he produced around this time. Blake was highly critical of Reynolds, an older and more established artist who, as President of the Royal Academy of Arts, embodied what Blake saw as the formulaic and stultifying ideals of the academy; his teeming marginalia to Reynold's treatise serves in some ways as a conscious affront to these ideals. But if The Ancient of Days also encapsulates the rational spirit Blake was wary of, the undeniable majesty of the figure also reflects his belief in human beings' visionary power, just as his famous and beautiful line from Auguries of Innocence compels the reader "To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/ And Eternity in an hour".

With his oppositional critiques of the art establishment, Blake set the stage for artists later in the nineteenth century, like the French painters Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, who deliberately set about to challenge academic paradigms. The Ancient of Days sums up something of the spirit Blake was opposing, but also of the spirit he was endorsing. It is also known to have been one of his favorite images, an example of his early work, but also one of his last works, as he painted a copy of it in bed shortly before his death.

Watercolor etching - Private Collection

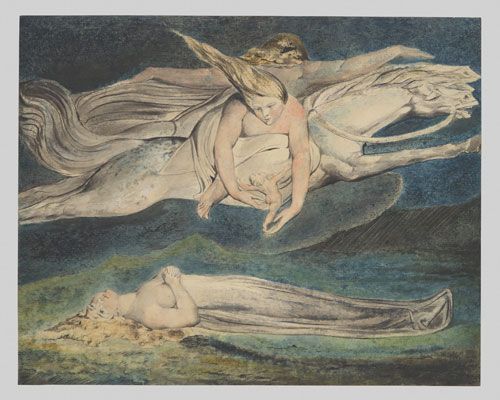

Pity

This piece, like Songs of Innocence and Experience, was made using Blake's illuminated printing technique. It seems to portray two cherubim, one of whom holds a baby, on white horses in a darkened sky, jumping over a prostrated female figure. The image is generally understood as an interpretation of a passage from Shakespeare's Macbeth: "And pity, like a naked new-born babe,/ Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubin, hors'd/ Upon the sightless couriers of the air,/ Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye".

Blake's use of blues and greens, contrasting with the whites of the figures, grants the work a nocturnal, dreamlike quality. Indeed, some scholars have questioned the extent to which the piece draws on Shakespeare's verse, suggesting instead that it might depict figures from Blake's own imaginative pantheon, as its visionary intensity seems to imply. The figure turning away from the viewer might be the god Urizen, for example, the face leaning down from the horse that of Los, an oppositional force to Urizen but also his prophet on earth, who has taken on the female form of Pity - often embodied in the character of his partner, Enitharmion - to enact Urizen's will. The woman below might be Eve, fulfilling the biblical prophecy that "in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children" by generating the miniaturized male figure cradled in Los's arms. By this reading, Pity represents the fall of man, in particular the moment when he becomes aware of his sexuality, and his subjugation to God.

Through mythological and literary-inspired works such as Pity, Blake would exert an immense influence on the course of post-Romantic art, including on the Pre-Raphaelites, who often drew on literary and Shakespearean themes, as in John Everett Millais's Ophelia (1851) and John William Waterhouse's Miranda (1916). The hallucinatory quality of works such as Pity, meanwhile, along with their apparent deep allegorical significance, would have a profound effect on movements such as Symbolism and Surrealism.

Relief etching, printed in color and finished with pen and ink and watercolor - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

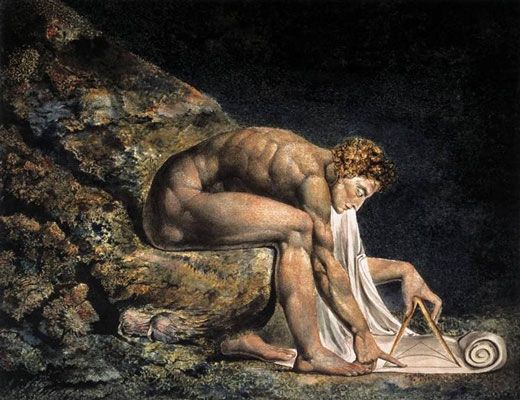

Isaac Newton

In this, perhaps Blake's most famous visual artwork, the mathematician and physicist Isaac Newton is shown drawing on a scroll on the ground with a large compass. He sits on a rock surrounded by darkness, hunched over and entirely consumed by his thoughts. This engraving was developed from the tenth plate of Blake's early illustrated treatise There is No Natural Religion, which shows a man kneeling on the floor with a compass and features the caption "He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only, sees himself only".

For Blake, Newton was the living embodiment of rationality and scientific enquiry, a mode of intelligence which he saw as reductive, sterile, and ultimately blinding. Isaac Newton is clearly a critical visual allegory, therefore, the sharp angles and straight lines used to mark out Newton's body emphasizing the repressive spirit of reason, while the organic textures of the rock, apparently covered in algae and living organisms, represent the world of nature, where the spirit of human imagination finds its true mirror. The deep, consuming black surrounding Newton, generally taken to represent the bottom of the sea or outer space, indicates his ignorance of this world, his distance from the Platonic light of truth. The compass is a symbol of geometry and rational order, a tool and emblem of the stultifying materialism of the Enlightenment. Blake's scorn for the scientific worldview, which also gave rise to his famous depiction of the god Urizen in The Ancient of Days - another figure who tries to measure out the universe with a compass - is summed up by his assertion that "Art is the Tree of Life. Science is the Tree of Death".

Blake's Isaac Newton has been the subject of numerous reproductions, homages, and reinterpretations, and the figure of Newton himself is probably Blake's best-known visual image, perhaps because it sums up his creative credo so perfectly. The image is also famous because it has proved so fascinating to subsequent artists. In 1995, the British pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi created a large number of bronze sculptures inspired by Blake's work, including a huge sculptural homage to Blake's Newton - though both curvier and more machine-like than its predecessor - which now sits outside the British Library in London.

Engraving - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

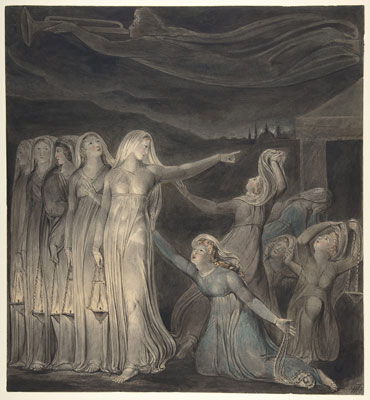

The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins

The painting, finished in pen and ink, illustrates a passage from the Bible, a prophecy described in the Gospel of Matthew as having been used by Jesus to advise the faithful on spiritual vigilance, describing how "A trumpeting angel flying overhead signifies that the moment of judgment has arrived". Blake contrasts the elegant and wise virgins on the left, prepared for the trumpet's call from the angel above, with the foolish virgins on the right, who fall over their feet in agitation and fear. The Parable was commissioned by Blake's patron and friend Thomas Butts, one of a huge number of tempera and watercolor paintings completed by Blake at Butt's behest between 1800 and 1806, all depicting Biblical scenes.

Though his own faith was anything but conformist, Blake had a profound respect for the Bible, considering it to be the greatest work of poetry in human history, and the basis of all true art. He often used it as a source of inspiration, and believed that its allegories and parables could serve as a wellspring for creative spirit opposing the rational, Neoclassical principles of the 18th century. The message of Matthew's passage is enhanced here by strong tonal contrasts, the graceful luminosity of the wise women contrasted with the ignominious darkness surrounding them.

Works such as The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins were influenced by various Renaissance artists who had explored similar, Biblical themes, and whose work Blake had devoured as a child. Leonardo da Vinci's The Adoration of the Magi (1481-82), The Annunciation (c. 1474), and The Last Supper (c. 1495-98) are good examples of such works, as are Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel frescoes (c. 1508-12), and Fra Angelico's The Madonna of Humility (1430). By not only entering into dialogue with these pieces, but by putting his own gloss on the moral and emotional dynamics of the scene, Blake expressed the ambition of his religious vision.

Watercolor, pen and black ink over graphite - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

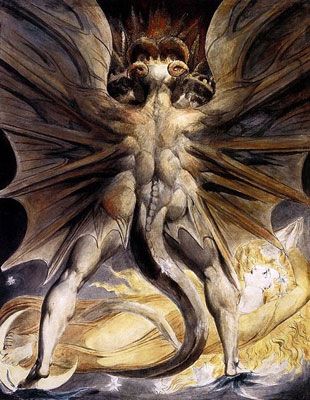

The Great Red Dragon and The Woman Clothed in Sun

This ink and watercolor work depicts a hybrid creature, half human half dragon, spreading its wings over a woman enveloped in sunlight. It belongs to a body of works known as "The Great Red Dragon Paintings", created during 1805-10, a period when Thomas Butts commissioned Blake to create over a hundred Biblical illustrations. The Dragon paintings represent scenes from the Book of Revelation, inspired mainly by the book's apocalyptic description of "a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads".

The Great Red Dragon is an example of Blake's mature artistic style, expressing the vividness of his mythological imagination in its dramatic use of color, and its sinuously expressive lines. The poet Kathleen Raine explains that Blake's linear style is characteristic of religious art: "Blake insists that the 'spirits', whether of men or gods, should be 'organized', within a 'determinate and bounding form'." This work also bears out Blake's claim that "Art can never exist without Naked Beauty display'd". Even in the portrayal of a destructive and aggressive subject, beauty, in particular the beauty of the human body, always plays a fundamental and central role in Blake's art: indeed, there is something of the human vigor and strength of Milton's Satan in the central, winged form.

Like Blake's Newton, his Great Red Dragon is an image which has permeated artistic and popular culture, particularly during the 20th century. Famously, the main character of Thomas Harris's 1981 novel Red Dragon obsesses over Blake's beast, believing that he can become the dragon himself by emulating its brutal power. The sequels to Harris's novel, Silence of the Lambs (1988) and Hannibal (1999) - adapted, like Red Dragon, into successful films - ensured the cultural resonance of Blake's monstrous but enticingly human creation.

Ink, watercolor and graphite on paper - The Brooklyn Museum, New York

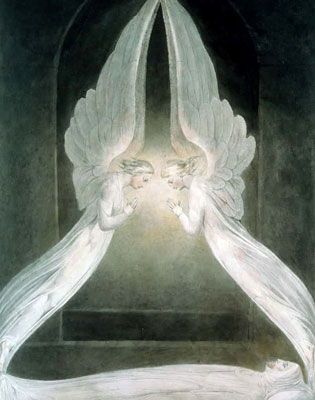

The Angels Hovering Over the Body of Christ in the Sepulchre

This watercolor and ink work, commissioned like The Great Red Dragon and The Wise and Foolish Virgin by Blake's great patron Thomas Butts, depicts a scene from the Biblical story of Jesus's death and rebirth. Following his crucifixion, Jesus's body was buried in a cave or tomb. As described in the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene visited the tomb to find two angels sitting "where the body of Jesus had lain". Upset at the body's absence, she began to weep, only to find Jesus standing beside her. Adapting the details of this scene, Blake places the two angels hovering above Jesus's body, probably portraying the moment just before his resurrection.

Though Blake's alteration of the details of the Gospel story are minor, they express his unorthodox, irreverently creative approach to faith and scripture. His depiction of the angels, for example, is said to be inspired by a passage from the Old Testament's Book of Exodus: "the cherubims shall stretch forth their wings on high... and their faces shall look one to another". The angelic forms also seem to allude to the wings which Blake claimed to have seen appearing on trees and stars as a child. As such, the image is testament to his belief in the central role of individual imagination in the interpretation of faith. In compositional terms, the darkness of the sepulchre, and the delicate whites and yellows of the aureoles around the angels' heads, give the painting an almost monochromatic quality, while the symmetry of the composition grants it a visual harmony in keeping with its spiritual significance.

In his imaginative adaptations of Biblical and religious scenes, Blake not only responded to a tradition of religious paintings extending back to the Renaissance, but also predicted the post-Romantic, imaginative adaptation of religious iconography in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, Symbolists, and other proto-modernist movements. As such, the vision expressed in works such as The Angels is both historically aware and subtly radical.

Pen, ink and watercolor on paper - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Ghost of a Flea

This delicate tempera painting, finished in gold leaf, depicts the ghost of a flea, represented as a combination of man and animal, staring into an empty bowl or cup. The figure appears to be pacing the boards of a stage, set against a backdrop adorned with painted stars, flanked by the heavy patterned curtains of a theater. His pose is suitably melodramatic, while the awkward weight of his body dwarfs his small, half-human head. This work was composed on a miniature scale, on a wooden board measuring roughly 21 by 16 cm.

Whereas much of Blake's earlier work draws on Biblical or literary themes, this painting is the expression of a macabre, darkly comic inner vision, and is considered amongst the most 'Gothic' of his works. According to John Varley, an astrologer, artist, and close friend of Blake's, who made notes on his practice, the painting was created after one of Blake's séances, during which he claimed to have been visited by the ghost of a flea who explained to him that fleas were the resurrected souls of men prone to excess. In this sense, the cup is a symbol for "blood-drinking", for overindulgence and intemperance. That interpretation is complemented by the half-human form of the spirit, suggesting a man in thrall to his animal instincts, while the stage might be a metaphor for society - the horror or scorn of the crowd - or for the vanity bound up with compulsive behavior.

The Ghost of A Flea is a singular manifestation of Blake's unique spiritual and imaginative temperament. Its late composition suggests that his visions became more idiosyncratic, more untethered from the collective, social view of reality, as he aged.

Tempera and gold leaf on mahogany - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Lovers Whirlwind

The Lovers Whirlwind illustrates a scene from the fifth canto of The Inferno, the first book of The Divine Comedy (c. 1308-20), by the medieval Florentine poet Dante. As the poem's protagonist, Dante himself, descends into the outer circles of hell, he comes across a number of people caught up in a whirlwind, shrieking with pain. Dante's guide, the Roman poet Virgil, explains that these are lovers "whom love bereav'd of life", punished for the illicit nature of their desire. They include Francesca, the daughter of a lord of Ravenna, who fell in love with her husband's brother Paolo, and was sentenced to die alongside him. Profoundly moved by their story, Dante faints, as portrayed in the painting to the right of the bearded Virgil. Above Virgil's head, Blake seems to depict Paolo and Francesca in a sphere of light, while the surrounding whirlwind of lovers ascends to heaven.

This painting belongs to a series of works commissioned by John Linnell, Blake's friend and second great patron, after the success of the illustrations for The Book of Job which Blake was already composing for Linnell. There was an established tradition of creating illustrations for the Divine Comedy, stretching back to the early Renaissance period, and to artists such as Premio della Quercia, Vechietta, and Sandro Botticelli. Blake was probably inspired by their work, but with typical immodesty he spoke of his superiority to many Renaissance masters in his handling of color, seen to be at its most accomplished in the Divine Comedy sequence. Blake believed that the effective use of color depended on control of form and outline, claiming that "it is always wrong in Titian and Correggio, Rubens and Rembrandt." As for his response to Dante, it is typical of Blake's critical stance on religious orthodoxy, and his belief in the sanctity of love, that he chooses to deliver the condemned lovers from their torment.

The Divine Comedy commission was left incomplete as Blake died in 1827, having produced only a few of the paintings. However, those that survive are noted for their exquisite use of color, and for their complex, proto-Symbolist, visionary motifs. Linnell's commission is also said to have filled Blake with energy despite his age and ill health; he reputedly spent the last of his money on a pencil to continue his drawings.

Pen and watercolor - City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham

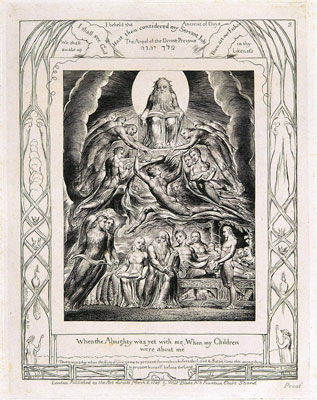

Satan Before the Throne of God: When the Almighty was yet with me

This engraving depicts the Old Testament character of Job surrounded by his children, while Satan sits above him in heaven, in front of a large sun, encircled by angels. The scene is an illustration of Job 29.5, which is written below the plate: "When the Almighty was yet with me, When my Children were about me". Satan Before the Throne of God is one of 22 engraved prints created towards the end of Blake's life, known as the Illustrations of the Book of Job. In the passage above, God has allowed Satan to kill Job's family and take away his wealth in order to test his faith. Though his relationship with God ultimately endures, at this point Job is lamenting his lost happiness, and questioning the creator's wisdom.

The Book of Job had preoccupied Blake since 1785, and was the subject of two previous watercolor paintings, created for Thomas Butts in 1805 and John Linnell in 1821. When he began the engravings Blake was therefore able to adapt various existing images, but the engravings became his most virtuosic response to the theme. The whole series expresses his fascination with the figure of Job who, like Blake, had lived a life of penury coupled with intense religious devotion. In compositional terms, the Job illustrations are Blake's most technically complex engravings, rendered with an extraordinary degree of tonal and figurative detail.

A marvelous final expression of Blake's imaginative and religious vision, Kathleen Raine describes the Illustrations of the Book of Job as "more than an illustration of the Bible; they are in themselves a prophetic vision, a spiritual revelation, at once a personal testimony and replete with Blake's knowledge of Christian Cabbala, Neoplatonism, and the mystical theology of the Western Esoteric tradition as a whole". She calls them as "a complete statement of Blake's vision of man's spiritual drama."

Engraving - Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery, Glasgow

Biography of William Blake

Childhood

William Blake was born in Soho, London, into a respectable working-class family. His father James sold stockings and gloves for a living, while his mother, Catherine Hermitage, looked after the couple's seven children, two of whom died in infancy. William, a strong-willed boy and an evident prodigy from a young age, often absconded from school to wander through the streets of London, or spent his time copying drawings of Greek antiquities; moreover, inspired by the work of Raphael and Michelangelo, he also developed an early fascination with poetry. Though his childhood was peaceful and pleasant, William began experiencing visions at the age of eight, claiming to see angels on trees, or wings that looked like stars. Though troubled by his stories, Blake's parents supported his artistic ambitions, enrolling him when he was ten at the Henry Par drawing academy, then a well-regarded preparatory school for young artists.

Early Training

The drawing academy turned out to be too expensive, and Blake was forced to quit after four years. It was intended that he would become apprentice to a master engraver but - so the story goes - when his father took him to meet his prospective employer William Ryland, the young Blake refused, declaring that "it looks as if he will live to be hanged!", a prophecy which, strangely enough, came true years later. In the end, William was apprenticed for five years to James Basire, an engraver to the Society of Antiquaries. Blake came to value his training with Basire, which had a great impact on his work: especially his various on-site drawings of Gothic monuments. In his spare time, the young engraver studied medieval and Renaissance art, especially Raphael, Michelangelo, and Dürer, who in Blake's view - as paraphrased by art historian Elizabeth E. Barker - had produced a "timeless, 'Gothic' art, infused with Christian spirituality and created with poetic genius".

When he was 21, Blake left his apprenticeship and enrolled at the Royal Academy. His time there was brief, however, reputedly because he questioned the aesthetic doctrines of the president Sir Joshua Reynolds, describing the Academy as a 'cramped imaginative environment'. Blake began earning a living as an commercial engraver for various publications, including popular books such as Don Quixote. At this time, in 1799, according to the poet and Blake scholar Kathleen Raine, Blake wrote to his friend George Cumberland - one of the founders of the National Gallery - "that his 'Genius or Angel' was guiding his inspiration to the fulfillment of the 'purpose for which alone I live, which is [...] to renew the lost Art of the Greeks'". Such a statement already makes clear not only Blake's admiration for Ancient Greek art, but also his sense of the interconnectedness of art and spirituality. Importantly, however, the spiritual guides who he claimed governed his artistic vision never steered him into the confines of organized religion: he never attended church.

In August 1782, at the age of 25, Blake met, courted and married Catherine Boucher, the daughter of a local grocer. Partly because the couple had no children, Blake devoted much time to teaching Catherine how to read, write, and draw, while Catherine helped her husband with his designs. In 1783, Blake published his first volume of poetry, Poetical Sketches; though sales were poor, the Blakes' finances were stable due to William's increasing popularity as an engraver. With his father's inheritance, Blake opened a shop with his friend James Parker.

In 1788, he used his method of "illuminated printing" for the first time in There is No Natural Religion, a small pamphlet containing his illustrated poetic and religious credo. Around this time, Blake's brother Robert died, probably of tuberculosis, after a long and grueling illness. His death had a profound impact on Blake, who began believing that Robert's spirit lived within him, inspiring him through visions and apparitions.

Mature Period

In 1795, Blake began a series known as the Large Colour Prints, depicting subjects from the Bible, Milton, and Shakespeare. Though Blake was never an isolated figure - he socialized widely, and attached himself to various cultural circles in London, through friends such as Henry Fuseli and James Barry - Raine notes that he was not an "easy man socially", being "proud, argumentative and violently opposed to current fashion, in his art and his philosophic and religious ideas alike". Certainly, Blake was radical in his political and religious views, and had no interest in conforming to social type. A kind of Platonist, he believed that the scientific view of the universe propagated by the Enlightenment was the "enemy of life", though, as the journalist Peter Blake adds, he was also an "artist with public ambitions", not yet the solitary hermit of his later years.

The same year he began work on the Large Colour Prints, Blake was introduced to Thomas Butts, who would become his main patron for several years, commissioning a large number of works. Loyal and supportive, Butts left Blake to pursue his private visions and impulses, "promising", as Raine puts it, "only to buy from him whatever he should paint." During this time Blake wrote: "I think I foresee better things than I have ever seen. My work pleases my employer, and I have an order for fifty small pictures at one guinea each, which is something better than mere copying after another artist."

The poet William Haley also became Blake's patron for a while, hiring him to undertake a commission in 1800, but Blake quickly became disillusioned with his assigned task, and, based at Haley's country estate at Felpham, sank into a depression, finding it impossible to "sacrifice his integrity as an artist for profit". The relationship between the two poets ended in acrimony, Haley describing Blake as his "spiritual enemy", and from around this time on, Blake found it increasingly hard to make a living, with engraving work drying up despite his connections with the London art world, and his ongoing commissions from Butts. Unlike his friends Fuseli and Barry, who held positions at the Royal Academy, Blake was not a member of the art 'establishment', and was never given the opportunity to undertake large-scale public works. In 1809, he lamented his lack of public commissions in England, writing in "The Invention of a Portable Fresco", a catalogue for his only public exhibition, that creating portable frescoes might be a good way to convince "visionless" patrons of the quality of his work.

Compounding his troubles, Blake's hallucinations and reveries increasingly led to him being perceived as insane: perhaps with some justification, as he is known to have publicly claimed that he revised Michelangelo's and Dürer's work on the artists' advice after communicating with them in visions. Coupled with his proud conduct and strongly-held beliefs - never humble about his craft, he once wrote to Butts that "The works I have done for you are equal to Carrache or Rafael" - Blake's mysticism drew him into ever more solitary patterns of existence. Nonetheless, he continued to generate a prodigious body of work, inspired by a deep faith in the power of imagination, and by his attentiveness to what he called "miracles". Blake once stated: "I know that this world is a world of imagination & vision. I see everything I paint in this world, but everybody does not see alike". Throughout his mature period, he often claimed to be encouraged in his work by Archangels, or to be in communication with historical and mythical figures such as the Virgin Mary.

For Kathleen Raine, "the bitterest irony in the story of Blake's failures and humiliations is that he was never unknown; on the contrary, he was in the heart of London's art world, and knew all the most famous artists and engravers of his day. And yet he failed where they succeeded, ousted by men of inferior talents and passed over by lifelong friends."

Later Work

Blake lived in Soho, the neighborhood of his birth, for almost his entire life, very rarely travelling. But despite this lack of worldliness, he made himself a highly cultured man, acquiring a large collection of classical art prints, for example. After years of poverty, he was forced to sell his print collection, but in 1818 Blake's financial fortunes turned once again when he met John Linnell, the man who would become his second great patron. Linnell provided Blake with financial stability in the later years of his life through his commissions and purchases, and also introduced Blake to a group of artists known as The Ancients, or The Shoreham Ancients, who had been brought together by their collective admiration for Blake's work. Like Blake, this group spurned 'modern' approaches to art and aesthetics, and held a broadly Platonic view of the universe. Towards the end of his life, then, Blake suddenly found himself a revered 'teacher' and leader. Indeed, the most talented of the Ancients, Samuel Palmer, is generally considered an inheritor of Blake's vision and technique.

Around 1820, Blake moved into a house near the Strand, spending his days engraving in a small bedroom. In 1821, at the age of 65, he embarked on a commission from Linnell to illustrate The Book of Job. Writing of Blake around this time, Samuel Palmer described Blake as "moving apart, in a sphere above the attraction of worldly honors". "He did not accept genius", Palmer added, "but confer it. He ennobled poverty, and by his conversation and the influence of his genius, made two small rooms in Fountain Court more attractive than the threshold of princes." The diarist Henry Crabb Robinson, another friend from this period, wrote in a letter of 1826 that anyone who met Blake saw in him as "at once the Maker, the Inventor; one of the few in any age: a fitting companion of Dante". Robinson described Blake as embodying "energy" itself, shedding an atmosphere "full of the ideal" all around him, despite his age and relative penury.

William Blake died in August 1827, at the age of 70. At the time of his death he was working on a set of illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy which are now considered amongst his best work. It is said that on the day of his death, as he worked frantically on these images, he proclaimed to his wife: "Stay! Keep as you are! You have ever been an angel to me: I will draw you!". A few hours later he passed away: the drawings are now lost.

Art critic Richard Holmes claims that when Blake died, "he was already a forgotten man", with sales for his engravings and painted poems scarcely reaching 20 copies over 30 years. Yet, for George Richmond, an artist associated with The Ancients, Blake "died like a saint...singing of the things he saw in heaven".

The Legacy of William Blake

William Blake is generally considered one of the great artistic polymaths, not just one of the finest poets in the English language, but also one of Britain's most revolutionary visual artists: the critic Jonathan Jones describes him as "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced". Blake is also remembered for the intricate and unique philosophical and religious schemas which sustained his work: whereas Romantic contemporaries such as J.M.W. Turner and John Constable drew inspiration from the landscape, Blake turned inwards, to an imaginative world based on the Bible and other religious and literary texts, taking his viewers on what Elizabeth E. Barker calls "journeys of the mind." Kathleen Raine explains that to the artist himself, Blake's works represented "'portions of eternity' seen in imaginative vision". She compares him to Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo, Dürer, Dante, and Fra Angelico (Blake's favorite artist) in his ability to create all-enveloping imaginative realms seemingly ex nihilo, offering us "fragments of worlds whose bounds extend beyond any of those portions their work embodied".

It is all the more ironic, then, that Blake was disregarded by artistic and literary society during his lifetime. Since it was common knowledge that he claimed to work from visions, he was generally categorized as eccentric or insane; only when the art critic Alexander Gilchrist, born a year after Blake's death, took to the concerted study of his art and legacy - resulting in the publication of The Life of William Blake in 1863 - was the full scope and significance of Blake's visions realised. Gilchrist described Blake's hallucinations as encoding a "special faculty" of the imagination, his avowed connection to the spiritual world evidence not of madness but of a form of "mysticism". Gilchrist's writing created a new context for the study of Blake's practice, just as Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti were responding afresh to the clarion call of Blake's spiritual intensity.

More generally, Blake's visionary and mystical works exerted an enormous influence on the later development of Romanticism in art, and, subsequently, on Pre-Raphaelitism, Symbolism, and even modernism. Blake's influence on literature has also been profound: Walt Whitman, W. B. Yeats, and Allen Ginsberg are amongst the poets profoundly inspired by him, while Blakean visions also had an afterlife in the abstract and psychedelic pop lyrics of the sixties, especially in Bob Dylan's post-beat dream sequences. In the present day, Blake's legacy extends all over high and popular culture, including art, literature, music, and film. It is believed, for example, that the illustrations for Lord of Rings and other movies on mythological themes were inspired by his imagery.

Art critic Alexander Gilchrist claims that Blake made his work for "children and angels; himself 'a divine child,' whose playthings were sun, moon, and stars, the heavens and the earth". In proclaiming the values of creative freedom, imaginative play, religious tolerance, and all forms of love, Blake created work of an enduring and profoundly positive value.

Influences and Connections

-

![Sandro Botticelli]() Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli -

![Leonardo da Vinci]() Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci -

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo -

![Fra Angelico]() Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico - John Milton

-

![Henry Fuseli]() Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli - John Flaxman

- James Barry

-

![John Everett Millais]() John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais -

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti]() Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti -

![George Frederic Watts]() George Frederic Watts

George Frederic Watts -

![Rockwell Kent]() Rockwell Kent

Rockwell Kent - John William Waterhouse

- Samuel Palmer

- George Richmond

- Edward Calvert

Useful Resources on William Blake

- Eternity's Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William BlakeOur PickBy Leo Damrosch

- William Blake: The Complete Illuminated BooksOur PickBy William Blake

- The Prophetic Books of William Blake: JerusalemBy Eric Robert Dalrymple Maclagan

- William BlakeOur PickBy Kathleen Raine

- William Blake: The Critical HeritageBy G.E. Bentley Jnr.

- Life of William BlakeBy Alexander Gilchrist