Summary of George Frederic Watts

George Frederic Watts was a visionary force with a paintbrush and a powerful persona as a man. Following an extended and inspirational trip to Italy, he took to wearing Renaissance robes on a daily basis. Indeed always unusual, he revealed an early interest in the unconscious mind by preferring to depict his subjects with their eyes closed. In style, he moved organically from Symbolism to abstraction whilst other artists remained far from this point. Overall, Watts was drawn to a cosmic synthesis of all things and as such deals in recurring notions and allegorical renderings of human strength and folly, never to be distracted by the fashions and expectations of the Victorian Age.

Indeed, his art straddles two worlds, that of Victorian romantic and nationalist symbolism, and that of a modernist insistence on digging to the depths and following the individual psyche. To privilege ideas and internal feelings during this era was rare, as was foreseeing the dehumanizing effects of commercialism. Indeed, a character in one of the artist's paintings, Mammon, is born as the monster to herald the absolute emotional disaster of the beginnings of a highly industrialized and capitalist society. Not only a painter, it is one of Watts' sculptures that well embodies his own character and ambition - a man on horseback looking out to the horizon with his hand to his forehead - he was an idealistic dreamer with an unwavering belief in humanity's inclination towards betterment.

Accomplishments

- Although Watts was a contemporary of the Pre-Raphaelites - he was well acquainted with members of the brotherhood and shared many of the same ideas - he is in fact more typical of a British artist in that he remained relatively isolated and unaffiliated with a particular movement. Like the Pre-Raphaelites though, and his friend Julia Margaret Cameron, Watts was inspired by literary references and practiced a holistic form of art making whereby poetry, philosophy, music, and general suggestions on how to live as a good person were all combined.

- In many ways, Watts was a man before his time. It was a radical statement of the day to say, "I paint ideas, not things", for such is the premise of Modern Art and following that, Conceptual Art. His paintings look forward to the intricate canvases of the French Symbolist Odilon Redon, and similar to Redon, Watts' early explorations of the unconscious, dream, the irrational, and the imagination, led him to expose monsters. Both artists successfully uncover horror and darkness in man, as well as creativity and strength, and as such, their malevolent human hybrid creatures (in particular depictions of the Minotaur) recall those of William Blake, Francisco Goya, and Pablo Picasso.

- Following extended travels in Italy, Watts was heavily inspired by the art of early and high Renaissance. He was influenced, not only by the soft color palette (particularly the hazy blues and icy pinks), but also by his desire to present an audience with a whole and epic story. Inspired most significantly by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel (1508-1512) and by Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel (1305) he consequently aspired to create his own 'House of Life' (a united series of many of his canvases dealing with specific emotions). Like the Old Masters, he considered his body of work to be at once a didactic narrative and a synthesis of spiritual ideas.

- A genuine and humble artist, Watts was also a political man. He bequeathed much of his art to the British nation in the belief that art should be accessible because it helped human development and was a tool for social reform (an idea shared by William Morris). He celebrated the heroic acts of ordinary men at Postman's Park, and built a community Ceramic Studio, and an Art Gallery within an Artists' Village in collaboration with his wife in the village of Compton in Surrey. Indeed, Watts' wife, Mary Seton Fraser-Tytler, was a suffragette, and Watts' sustained love and support for her, as well as his consistent return to the theme of the brutal mistreatment, limited choices, and unacceptable second-rate position of women in society, earn him the label as an early Feminist.

Important Art by George Frederic Watts

Found Drowned

Lying on her back, arms outstretched, the forlorn figure of a woman fills the bottom third of this imposing two-meter canvas. Her still face is highlighted whilst the distant industrial background is lost in a haze; a solitary shining star shines down on her lifeless body as a sign of celestial respect and acknowledgement of the women's individuality. The sad scene is framed by the Waterloo Bridge; underneath the woman, dressed in red (perhaps to signify impropriety or sexual experience as the cause of her downfall), has been washed up by the mysterious deep flowing waters of the River Thames.

The piece is physically as big as its intended emotional message, which was that Victorian society was unjust and women were drowning in its hypocrisy. The painting marked one of Watts' first forays into social realism and highlights the artist's confrontation of the sexual double standards that faced women who fell pregnant out of wedlock at this time. The inspiration for the piece came from Thomas Hood's poem The Bridge of Sighs, in which an unnamed expectant woman throws herself to her death after being made homeless. Watts said himself that he wanted his work to be considered "poems painted on canvas". Sadly, it was often the case that Victorian "fallen women" - be they expecting babies but unmarried, shunned by lovers, or made destitute and hungry fro other reasons - would commit suicide by drowning themselves in the icy and unforgiving waters of the Thames.

Watts uses color to highlight the stark contrast between the woman's soul - who we are asked to consider with compassion - and the dark, uncaring city beyond. The figure's skin is almost luminescent against the black and blues of the dark and indifferent London cityscape. The palette of the city beyond recalls the wispy and feathered aesthetic techniques of his fellow artist, James Abbott Whistler, who was soon to make London his home. As Watts knew that Victorian society was not yet ready for the mirror that he held up to it - indeed, his exposure of the harsh and unrealistic expectation placed on women's shoulders - he cleverly refrained from exhibiting the painting for another 30 years to come.

Oil on canvas

Choosing

Watts was a prolific and successful portrait painter and his distinctive studies of women produced in a highly poetic and romantic spirit were very popular among Victorian society. The exquisite Choosing is one of his finest examples, depicting a classically beautiful, golden haired young woman tilting her head in a gesture of gentle eroticism in order to enjoy the imagined luscious scent of a bright red camellia. Her eyes are closed, repeating a favored and important motif for Watt's; he suggests that knowing comes intuitively from within, rather than as learnt response derived from the external world.

The model in this painting is in fact the artist's own teenage-bride Ellen Terry who he had married at the age of 46 (when she was 16). This sensuous image shares much in common with the Pre-Raphaelite style. Indeed, Watts too is extremely interested in allegory, and in the messages that he is able to convey using repeated motifs and poignant symbols. Camellias, though showy and beautiful, are scentless. Yet she is delicately holding close to her heart a clutch of violets. According to the art teacher and curator Wilfred Blunt, who wrote a biography of Watts, Choosing shows Terry "trying to decide between the rival merits of a showy, scentless camellia and the humble but fragrant violets held close to her heart". Do the flowers in this respect signify two different men vying for the young girl's affection? Or do the flowers stand as a choice at this point between the two states of innocence and experience? Or between the life as a man's lover, or the life of an independent actress?

At this point of the painting's creation, Terry had given up a career in acting in order to live with Watts and to be educated by him. The union was less shocking than it would be today, but it was disastrous nevertheless. Terry, the subject for a number of Watt's symbolist portraits left her husband in under a year and returned to the stage, later becoming the preeminent Shakespearean actress of her age. The portrait remains a skilled testament to love and beauty, an illustration that Watt's shared appreciation for flora, lavish color schemes, and youthful female beauty like the Pre-Raphaelites. Watts though, also made pictures without such obvious affiliations and as such with further extended possibilities of meaning and influence.

Oil on canvas

Love and Life

Here Watts depicts the sturdy winged male figure of Love reaching down tenderly to help the female personification of Life as she fumbles her way up the rocky mountain path of existence. Pale, weak, and beautiful, she turns her head upwards to the guidance of Love. The message is similar to that of Found Drowned, whereby an expectant lone woman is left destitute. No doubt at some point before this said woman lost her life, Love reached out a hand to her also. Unfortunately, the impact of consummated love in the Victorian period (especially out of marriage) often heralded disastrous consequences.

Watts said himself that this was one of his of his best paintings "to portray my message to the age". As the pair ascends, violets blossom on jagged stones and clouds disperse to reveal a clear blue sky. Love is here understood as altruism and compassion, rather than physical passion, or indeed, if it is not to ruin a woman that it importantly is better kept this way. This was an important moral message for the Victorian age - when blind adherence to the teachings of the bible began to give way to scientific reason and more individualist ways of thinking. It was, in the artist's words, "a painted parable".

Watts believed that art should "lift the veil that shrouds the enigma of being" and he wanted this piece to represent in a universal symbolic language the emotions and aspirations of life. He donated the piece to the U.S. where he was growing in popularity, in the hope that it would spread the painting's double (and at times paradoxical message) - that Life cannot reach its transcendent best without the help of charitable Love, but also that women are suffering in contemporary society.

A critic at the time, G.K. Chesterton said: "More than any other modern man, and much more than politicians who thundered on platforms or financiers who captured continents, Watts has sought in the midst of his quiet and hidden life to mirror his age...In the whole range of Watts' symbolic art, there is scarcely a single example of the ordinary and arbitrary current symbol...There is nothing there but the eternal things, day and night and fire and the sea, and motherhood and the dead." In many ways this man was a poet and a visionary, interested only in powerful recurring symbols and never distracted by fashion or temporary societal ills.

Oil on canvas

Mammon

Watts increasingly believed that society was being made rotten by the worship of wealth and riches, and his portrait of Mammon is a harsh one. The work sought to provide an important moral message; the artist was rallying against the destructive motivating force of greed that was prevalent in society. He had become disturbed by the increasing poverty and destitution and began to question industrialization's dehumanizing effects. Along with social commentators including William Morris, John Ruskin, and Robert Carlyle, he began to question the benefits and purpose of modern industry and commerce. In 1880 he wrote, "Material prosperity has become our real god, but we are surprised to find that the worship of this visible deity does not make us happy".

As such Mammon is suitably a hideous visual spectacle and an uncomfortable work to behold. The canvas is dominated by a palette of violent red and the viewer is confronted by an ugly satanic being - rouge, repulsive, and bulbous - resting his feet upon two slumped bodies while he sits on a throne decorated with skulls. The mere mortals appear to have crumpled under the rule of this monstrous tyrant; he recalls murderous literary characters including Ovid's King Midas, and villains in Edmund Spencer's epic poem, The Faerie Queen (1590). Crowned and sneering, the kingly beast looks to the viewer resided to fate of hedonism, greed, and corruption. A closer look at the piece reveals great texture in technique, as though Watt's brushstrokes are scars that resist and writhe, and pull away from the flat canvas. It was because of this highly gestural mark making that when the art critic Roger Fry was asked to account for the way that Cubism seemed to have burst out of nowhere in 1907, he explained, no - quite the opposite in fact - "it was quite easy to make the transition from Watts to Picasso; there was no break, only a continuation".

Oil on canvas

Hope

Hope is arguably the most lyrical, poetic, and memorable of Watts' paintings. It is a profound and remarkable image that insightfully looks backwards to early Renaissance frescos (in both palette and symbolism) and forwards to modernism and Surrealism (in that the subject is blindfolded and thus looks within to the imagination for guidance). This striking picture depicts, at its centre, the blindfolded figure of Hope seated on a sinking globe, playing a broken lyre. She 'hopefully' bends her head to listen to the music, revealing that her faith remains despite the sadness and desolation of her situation. Watts wrote of this painting at the time: "The lyre has all the strings broken but one out of which poor little tinkle she is trying to get all the music possible, listening with all her might to the little sound." Watts made two versions of this same painting, and the first version (now in a private collection), displayed the same motif of the single star that we have already seen in Found Drowned. This sign of optimism however, was removed from the second version of the image, bequeathed to the nation, completed sadly with a little less "hope".

The sensitive and melancholy rendering of grey, green, and blue hues of this piece, similar to that of Watts' 1879 Portrait of Violet Lindsay hint at Picasso's blue period, which the infamous Spaniard began just five years later. The principle concerns of the work are not however color, light, and tonality. Watts' main focus, as is typical, was the Symbolism and great depth of meaning that lay beyond the form, line, and shape of his subject matter. Indeed, the enduring power and influence of this painting can in no way be underestimated. In 1959 Martin Luther King, inspired by the painting, wrote a sermon on the subject of hope, as did Jeremiah Wright a generation later. Barack Obama was watching Wright's speech in 1990, and he himself went on to write The Audacity of Hope, the title of both his rousing address to the Democratic Convention in 2004 and his manifesto, published two years later. The notion of Hope, for better or for worse, defines us as human beings. Whilst there is general consensus that these speeches mentioned, including Shattered Dreams by Martin Luther King, were directly inspired by Watts, the relationship between Watts and Picasso is more ambiguous. There is no literal proof that Picasso knew and followed the work of Watts. However, as two deeply questioning spirits, they both uncover and make visible sorrow and hidden demons.

Oil on canvas

The Sower of the Systems

The Sower of the Systems enigmatically captures a moving figure from behind, as he moves through his dance or runs on a journey, while light and sparks arc from his majestic outstretched arms. He is priest, shaman, even God-like, shrouded in blue robes and barefoot, accompanied by encircling rings of magic. The piece is alive with movement and color and is utterly unlike any other work completed in this period. Interestingly, Watts had in fact seen the rings of Saturn through his telescope, cleverly asserting that the cosmic elements of this piece not only echo the artist's love of stargazing, but also bring his dreamlike vision closer to everyday reality. Not only a pre-curser to Abstraction, and the Watts' usual nod to the poetic atmospheres of Romanticism and Symbolism, the painting is also comparable to the much later experiments of the Italian Futurists. Wartime Europe saw deepening exploration into the powers and meaning of movement, speed, and in turn, progress. The Vorticists adopted the theme in England, but Watts had considered the idea 40 years before.

It is crucial, to properly understand the work's importance, that we know it was produced years before any form of abstract painting came into popular being. The work for its time was ambitious, original, and striking in its composition, and what's more, it actually impressed critics with its daring modernity. Still though, Watts himself was not convinced by the overall success of the work. He said: "My attempts at giving utterance and form to my ideas are like the child's design, who being asked... to draw God, made a great number of circular scribbles, and struck his pencil through the centre, making a great void. This is utterly absurd as a picture, but there is a greater idea in it than in Michelangelo's old man with a white beard."

The painting was completed two years before Watts died and in many ways reads as his attempt to unite and reconcile many things, perhaps including apparent contradictions at work between science, art, and religion. On his deathbed in 1904, Watts said he witnessed the universe coming into being, "the breath of the Creator acting on nebulous matter causing agitating waves and revolving lines to fly out in all directions". It was as though he had already seen this, and as such, the artist truly was a visionary, both in life and in death.

Oil on canvas

Biography of George Frederic Watts

Childhood

George Frederic Watts was born in Middlesex, a historic county in the south east of England that has since been swallowed up by London. His father was a piano maker and because of his love for music, named his son after the composer, George Frederic Handel, who shared the same birthday. The young Watts was a sickly child and as such was unable to attend school regularly. He was instead home-schooled by his father, both in a conservative Christian fashion but also with the introduction of interesting literature including Homer's The Iliad. Watts loved and held dear the inspiration that such ancient Greek texts brought him throughout his career, but resented and rejected the strict sabbatarian and evangelical household in which these were presented. Watts was deeply affected by the severe routine that he experienced on Sundays, and general restriction had a negative impact on his overall view of organized religion. As such, he questioned traditional biblical teachings and his own reimagining notions of 'the creator' can be seen in works through to the end of his life.

Watt's artistic talent emerged early - drawing often - and by the age of ten he had already found inspiration in the studio of the sculptor William Behnes in Dean Street, Soho. This relationship led him to discover the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum - the works, also known as the Parthenon Marbles, are a collection of Classical Greek sculptures made under the supervision of the architect and sculptor Phidias and his assistants. "The Elgin Marbles were my teachers. It was from them alone that I learned", Watts said. Asides from beginning to amass his own personal awareness of classical art history, like many Victorians, Watts' childhood was tragically overshadowed by death. He lost his three younger brothers at an early age and his mother died when he was nine. Traces of these early experiences of trauma never really leave the artist's work; he spent much of his career exploring the themes of death, mysticism, and spiritual purpose in life.

Early years and training

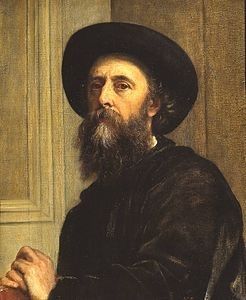

Watts initially studied work by respected Old Masters, as well as more immediate predecessors including Richard Westall and John Hamilton Mortimer, and made accurate imitative sketches of various works. He joined the Royal Academy at the age of 18 and further developed his art historical studies. At this point however, he had already secured the patronage of Alexander Constantine Ionides and began to work successfully as a portrait artist. In 1837, Watts exhibited his much-praised A Wounded Heron painting in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.

Although Watt's humble background prevented him from taking the traditional Royal Tour, he did manage an extended stay in Italy during 1843, at which time he further cultivated his love for Italian Renaissance painters. Indeed, his love of classicism earned him the title "England's Michelangelo". Upon his return to England he started to wear the rich, exuberant, and scholastic robes and skullcap of a Renaissance sage, and his friends started to call him "Signor".

Watts forged a reputation as an excellent portraitist, gaining critical acclaim and being commissioned to paint the imminent political and cultural figures of the time. He became prolific, producing vast amounts of art covering almost every theme across a range of media. While his earlier works were traditional in their composition and had a strong narrative, he later departed from the popular romantic style and moved towards a more complicated allegorical mode that examined the complexities of a rapidly changing era. Indeed, one critic wrote: "The studio of Mr Watts is not merely a gallery of pictures but a museum of ideas."

Mature Period

Later in the 1840s Watts reached a turning point in his art as he moved towards social realism - a term used for work designed to draw attention to the everyday conditions of the working class and to voice the authors' critique of the social structures behind these conditions. Watts had become disturbed by the increasing poverty seen in London and Ireland, where mass starvation and disease had become symptoms of the potato famine. This was exacerbated by his own failing health - he suffered from chronic headaches - and a depressed state of mind and the subject matter of his work took a bleak turn. This can be seen in four paintings of note: Found Drowned (1848-50), The Seamstress or The Song of the Shirt (1850), The Irish Famine (1845-49) and Under a Dry Arch (c. 1848-50). He was influenced by the social theory of the philosopher Thomas Carlyle, who said art should be "both spiritual and intellectual" and that artists should play a political role. This was a revelatory moment for Watts and he began to express social concerns in a symbolic manner.

Around this time he became a frequent visitor to Little Holland House, in London's Kensington, which had become a bohemian artist's hub, attracting Watts' friends Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Makepeace Thackeray, Alfred Tennyson, and Frederic Leighton. His host, Sara Princep, said later: "'He came to stay three days; he stayed thirty years." He helped the Princep family to renew their 21-year lease on the property and lived with them there for the entire period after.

Watts was an enigmatic man and would often shun the limelight. As his painting became more powerful and more renowned, he twice refused a baronetcy offered by Queen Victoria, and other honors, including a reported offer to become president of the Royal Academy. His closest brush with scandal came in 1864 when he met the young and beautiful actress Ellen Terry. Terry was also famously immortalized in an exquisite portrait photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron. She became Watts' muse and whilst he initially thought of adopting her, he then changed his mind and decided to marry her instead despite their 30-year age difference - she was just 16. The marriage was short-lived and they separated after ten months. Watts agreed to pay her £300 a year "so long as she shall lead a chaste life".

In 1886, Watts was remarried to the Scottish potter, designer, and pioneering suffragist Mary Seton Fraser-Tytler in Surrey. Again there was an age difference - Mary was 36, whilst Watts was 69. Despite this, the pair had much more in common, including a belief that art could and should communicate something worthy to everyone, to uplift the soul and mind, and to comfort the troubled. A few years later they leased land at Compton, Surrey, and commissioned the Arts and Crafts architect Sir Ernest George to build their home Limnerslease. The couple moved here in 1891 and henceforth lived out their years producing work that spoke of their strong shared social conscience. Both Watts and Fraser-Tytler had very progressive socio-political positions. They were good friends with George Meredith, a woman's suffrage supporter, and Josephine Butler, a women's rights worker. Watts painted the portraits of both of these people and the four figures together existed at the heart of a wider emergent Feminist community at the time. This interesting theme of Feminism surrounding Watts after his marriage to Fraser-Tytler is the subject of a 2016 academic journal article published by Taylor and Francis.

Watts believed that art could transform lives both on a spiritual and practical level. So much so that he opened his studio in London to the public for free on certain days. Furthermore, in Compton he and Mary set up a pottery house to train local people in ceramics. This was crucial at a time when farm work was becoming scarce due to industrialization. Compton Pottery closed in the 1950s but his home now houses an Artists' Village ensuring the Watts legacy lives on.

Late Years and Death

In 1884 Watts was bestowed with the honor of becoming the first living artist to be offered a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Indeed, he was hailed at this time to be "the greatest painter since the Old Masters". Social concerns continued to preoccupy the artist - although themes were also highly poetic and allegorical as well - and in 1887 he wrote to the national press proposing a record of heroic deeds of common people as a fitting jubilee memorial. Thus, Postman's Park in the city of London is now home to a remarkable structure on the walls of which are a series of ceramic tiles commemorating long ago acts of heroic self-sacrifice by ordinary men, women, and children.

Ultimately, Watts successfully attained celebrity status during his lifetime and by 1902 was among the first person to be honored with Edward VII's Order of Merit. He continued to be prolific, working well into his eighties, despite battling deafness and rheumatism. His life ended in 1904, when the Times Newspaper wrote "the most honored and beloved of English artists is dead". By this point, he was considered one of the most famous painters in the world, having produced around 800 canvases.

The Legacy of George Frederic Watts

Despite being famous at the end of his career, Watts' critical appeal quickly declined, and after his death he was dismissed as "one of the great failures of British art". He was branded "irrelevant" and sidelined as a Victorian oddity, with the work of the Pre-Raphaelites often being remembered as Britain's most interesting contribution to art at the time.

However, early in the 1970s the then president of the Royal Academy, Christopher Le Brun rediscovered the work of Watts, stating "it was thrilling to be confronted with such huge intellectual and artistic ambition". Le Brun visited the Watts Gallery in Surrey and was further impressed to discover a physical legacy - as well as the usual legacy of influence - connected to Watts and his art. As well as housing a cast of the equine sculpture Physical Energy - an imposing 4-meter tall statue of a man riding a rearing horse which had been Watts' last submission to the RA's Summer Exhibition in 1904 - the Watts Gallery gives site to a large pottery, a chapel, various gardens, and a woodland. The Gallery claims: "We follow in the footsteps of our founders by using the transformative power of the arts to move, inspire and engage and by driving social change, self-development and empowerment through the arts."

From the perspective of concept and ideas, it is Watts' later works, including Hope (1886) and Dweller in the Innermost (c. 1885-86) that best reflect the artist's worldview; he had an exceptional imagination and explored themes mostly avoided by other painters. He left behind a body of Symbolist work that addresses the Victorian loss of faith, child prostitution, and a certain immaturity in the dealing with emotions. Like the artists William Morris and William Blake he saw art as a means to social reform, as well as the most valuable tool to free the human mind and imagination from societal restraints.

Watts' inspirational reach can be seen in the work of a new generation of modern artists. Hope, especially, with the figures' intentionally distorted features and broad sweeps of blue are interesting to consider as echoed in Pablo Picasso's The Old Guitarist (1903-04). Piet Mondrian declared too that he felt a clear affinity for Watts' moody transcendentalism and said that he had particularly been inspired by the Watts' trio of paintings of Eve, exhibited in London. The Impressionist Camille Pissarro said he was influenced by the artist's philosophy. Watts' work also had a profound influence on the English painter Annie Louisa Robinson Swynnerton, as well as on that of one of the most important and innovative photographers of the 19th century, Julia Margaret Cameron, his friend and protégé. His work directly feeds into the deep exploration of Symbolism by the painter Odilon Redon, and beyond this movement, even into the dreamy and experimental early collage work by the Surrealist Max Ernst.

Influences and Connections

-

![Lord Frederic Leighton]() Lord Frederic Leighton

Lord Frederic Leighton -

![Julia Margaret Cameron]() Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron - William Behnes

-

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Piet Mondrian]() Piet Mondrian

Piet Mondrian - Annie Louisa Robinson Swynnerton

Useful Resources on George Frederic Watts

- G. F. Watts: Victorian VisionaryBy Mark Bills and Barbara Bryant / 2008

- England's Michelangelo: A Biography of George Frederic WattsBy Wilfrid Blunt / 1975

- G.F. WattsBy G.K. Chesterton / 1904

- G.F. Watts: The Last Great VictorianBy Veronica Gould / 2004

- The Life-Work of George Frederick WattsBy Hugh MacMillan / 2017