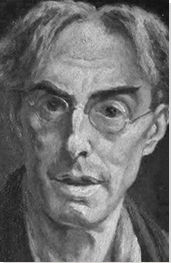

Summary of Roger Fry

Roger Fry was Britain's most influential art critic during the first half of the twentieth century. He was, in point of fact, something of a polymath, showing a vast cultural range and an upper level of attainment as a painter, designer, broadcaster and curator. But it is for his legacy to art criticism and art history that Fry remains most admired. It was Fry who invented the term Post-Impressionism, and it was he who did more than any other individual to introduce contemporary French art to the British public. Fry was co-founder of one of Britain's most established art journals, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, while his own painting reflected the influence of his great hero, Paul Cézanne. Having become a member of the famous Bloomsbury Group, he established a design workshop - The Omega Workshops - to rival that of William Morris and his Arts and Crafts Movement. Towards the end of his career Fry added a series of radio broadcasts for the BBC and a professorship at Cambridge University to his already imposing résumé.

Accomplishments

- Fry was amongst the first British art critics to advocate the importance of French modernism. Swimming against a tide of academic opinion, he saw a true artistic authenticity in their work and, with great verve and erudition, he defended the crude "child-like" qualities of the group that he would name the Post-Impressionists.

- Rejecting the tradition in art criticism established by John Ruskin through which the aesthetic judgement rested on the critics' moral position in relation to the work(s) under scrutiny, Fry formulated a more objective form of analysis. He demonstrated a more technical, more objective, approach to art criticism that focused on the way the psychology of the artist in question evolved in the style of his paintings.

- Through his Omega Workshop, Fry brought the decorative colors and designs of the Post-Impressionists and Cubists into interior design. There were obvious similarities between what Fry was trying to achieve and the goals of his predecessor William Morris. But Fry's Omega project was motivated by nothing more than to transfer fine art into the sphere of everyday living, whereas Morris's anti-industrialization Arts and Crafts Movement saw itself as part of a bigger social project.

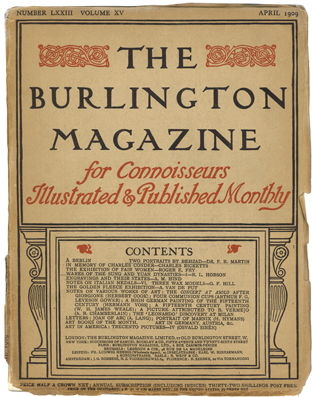

- Fry did more than any other of its senior contributors to establish the critical integrity and credibility of the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. Through the magazine, and indeed through his series of broadcasts on the BBC, Fry widened the geographic scope of Western art history by bringing Chinese and African art into its historiography.

Important Art by Roger Fry

Agony in the Garden (1465)

Originally published in 1899, Giovanni Bellini was Roger Fry's first book-length monograph and was presented as a "rediscovery" of the great Venetian master for a twentieth century audience. The book, which remains a source text for Bellini scholars, stands also as a document of Fry's critical method - which he offered as a move away from the idea of perception towards a more technical means of analysis by which one might investigate the stylistic evolution of the artist and psychological "performances" of his subjects. Fry would return to Bellini through a series of further essays over subsequent years.

Fry argued that Agony in the Garden represented a major turning point in Bellini's career; marking a transition period from his early "Paduan" style towards the "Venetian" style through which he became world renowned. Though a native of Venice, Bellini worked as an assistant to his father in Padua, a city to the west of Venice. While working on a chapel in Santo, Bellini fell under the tutorship of Francesco Squarcione who had already trained well over one hundred painters in the so-called "Paduan style". The "Paduan style" involved linear designs based on an old Paduan tempera technique whereby, in Fry's words, "light and shade were put on by small hatched strokes with the point of the brush". Fry compared Bellini's version of Agony in the Garden to that of Andrea Mantegna's; the latter being an exemplar of the Paduan style. While Bellini's Agony shared similarities with Mantegna's Agony (such as the figure of Christ), Bellini's technique was not consistent throughout the painting with the hill (on which Christ kneels), the distant valley and the flowing drapery of Saint Peter all breaking with the linear conventions of the Paduan style. Given that Bellini's technique expressed the artist's personal relationship with his natural surroundings (it amounted to more than a methodological exercise in other words), Agony in the Garden represented a religious interpretation born of an artistic imagination that Fry argued was far ahead of its time. As he put it, "Bellini shows already that perception of the emotional value of passing effects of atmosphere, which is often supposed to be a peculiarity of the art of this [the nineteenth] century".

The National Gallery, London

The Girl with Green Eyes (1908)

Before 1910, progressive overseas art had rarely been seen in Britain. Because it was so alien, the Manet and the Post-Impressionists opened, in the words of The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs' editorial to celebrate the exhibition's centenary, "to a hailstorm of critical abuse". It quoted the views of one visitor "who thought most of the pictures were 'abortions'" while bemoaning the fact that the galleries themselves were "'uncomfortably crowded with a horde of giggling and laughing women'". The general consensus amongst critics and public alike was that the collected works were "boring, ordinary, unelevated [and] without distinction". It was agreed, for instance, that Cézanne's Portrait of Mme Cézanne had "no feminine allure to recommend her", Matisse's The Girl with Green Eyes "was common, even brazen", and while Gauguin's Tahitian scenes "had some exotic pulling power", his "'savages' could hardly be hung on one's wall". The Burlington recorded that the exhibition had amounted to "an unsettling visual democracy that undermined the cultured assumptions of the educated classes" and even "the brilliant colour was an affront to such refined sensibilities, conditioned as they were by the muted palette of the New English Art Club, by Whistlerian tonalities or the decorum of society portraiture".

The Burlington noted that while the exhibition had not made its "leading artists household names overnight", Fry had effectively set the ground for their widespread acceptance which reached its full fruition over the next decade or so: "Gauguin [...] became a figure of romance and rebellion, his life evoked a few years later in Somerset Maugham's bestselling novel The Moon and Sixpence; Van Gogh was the deranged genius of popular imagination, although the publication of his letters in the following decade evidenced the idea of him as an undisciplined lunatic; and Cézanne, from being an incompetent 'bungler', rapidly assumed shaman-like status in the development of Modernism". The Burlington's centenary editorial paid glowing tribute to Fry's daring, suggesting that it was the magazine's good fortune that its co-founder was using its pages to lead a celebration of the exhibition when other journals and critics were roundly condemning the "reckless" collection of works.

Oil on canvas - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

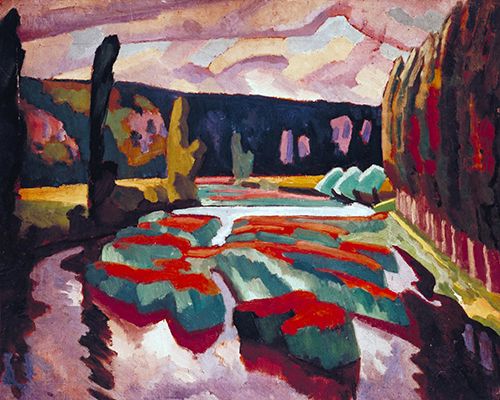

River with Poplars (c.1912)

Fry painted River with Poplars from a bridge at Angles sur l'Anglin near Poitiers in France. The painting was produced at the height of Fry's involvement with his two Post-Impressionist exhibitions at the Grafton Galleries and very clearly reflects the influence of Manet, Matisse, Gaugin, and Cézanne (around whom he had built his own theory on aesthetics). The style of this painting follows - even exaggerates - Cézanne through the subdual of all picture detail to the point of near abstraction. Here the emphasis is on organizing color into blocks with shapes - the clouds, river, the banks of the reeds - rendered as solid mass.

The work, which draws on the decorative qualities he had admired so much in the work of the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and the Fauvists. These mid-career works demonstrate Fry's willingness to experiment with radical forms, in the case of the latter, with the Cubist collage techniques being explored by Braque and Picasso. These experimental pieces were followed by a series of landscapes, such as The Artist's Garden at Durbins, Guilford (1915), which maintained his affection for Cézanne's "inner vision" while reintroducing his commitment to picture detail and a general shift towards a more naturalistic style that would follow him into the 1920s and 30s.

Oil paint on wood - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Post-Impressionist Room (1941)

Through his Bloomsbury Group connections Fry effectively created the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist rooms at the National Gallery in London. (John) Maynard Keynes would become a world renowned economist who helped found both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. He was also the founder of the British Arts Council. In 1918, while still a Treasury advisor, Keynes became a member of the Bloomsbury Group and Fry showed him a way to combine his two great passions: money and art. Fry told Keynes about an upcoming auction in Paris in which it would be possible to buy paintings by the likes of Degas, Cezanne, Manet and Gauguin at bargain prices.

Fry convinced his friend that these geniuses of contemporary French art were still largely unrecognised by the British public and they needed to be permanently on display in its capital city (ideally, in the National Gallery). On Fry's advice, Keynes and the director of the National Gallery, Sir Charles Holmes, travelled to Paris with £20,000 in French currency. Fully aware that the French would be reluctant to sell to a British bidder, Holmes disguised himself by shaving off his moustache and adopting a faux French accent. The war was still raging in the trenches of Flanders and northern France, and, as luck would have it (from a British point of view at least), once the sale was underway the auction-house was physically shaken by the roar of shelling from a German super-gun leading many bidders to flee the building in fear for their lives. Keynes and Holmes stood their ground and as bidding fell off they were able to acquire several masterpieces at bargain prices. These acquisitions would lead to the formation of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist rooms at the National Gallery which are now the most visited in the entire gallery.

The National Gallery, London

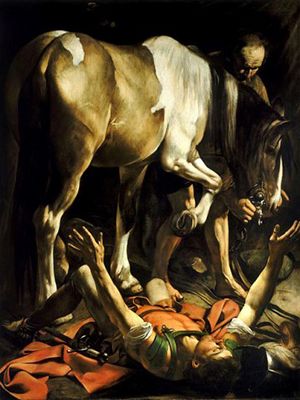

The Conversion of St. Paul (1600-01)

In October 1922, Fry published an article in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs entitled 'Settecentismo' in which he lamented Caravaggio's style in a comparison with Futurism and modern cinematography ("what an impresario for the cinema Caravaggio would make" Fry exclaimed). Fry's argument was that Caravaggio's style instigated a long tradition in the visual arts that led to the "modern popular picture", namely: Salon painting, Victorian narrative painting, Futurism, and, finally, the new art of cinematography.

Fry's criticism of Caravaggio linked to the Italian Futurist movement in their shared "love of violent sensations and uncontrolled passions" which was in his view part of "the Italian spirit which also created Fascism [and a] ruffian and swash - buckling attitude [that attributed] aesthetic value to violent sensations". For Fry, this road led to nothing less than the "complete destruction of art". Fry's aesthetic preference was for a more authentic, less melodramatic, art that revealed the artists' sensations towards their material. It was this "sensibility" that the true artist could convey to the viewer through their unique designs of form and colour. Artists like Caravaggio merely denied the viewer the intellectual satisfaction of discovering this higher pleasure. The "modern popular picture" tended to fixate on pointless picture detail - or fragments of reality - which merited admiration but lacked the essence of what art should be. Reaching its current apotheosis in the cinema (with its fixation on the close-shot), the "modern popular picture" delivered a direct, but fleeting, emotional thrill.

In 1922 the language of cinema was still in its infancy and was considered strictly the art of the masses. Three years later Fry had joined the Film Society of London with the aim of raising awareness of the intellectual importance of cinema as an art form.

Oil on canvas - Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

Preparation for the Funeral (The Autopsy) (1867-69)

Fry published Cézanne. A Study of his Development in 1927. Reviewing it in 2009, the historian Richard Verdi called it "a landmark book which is arguably still the most sensitive and penetrating of all explorations of Cézanne's paintings". Yet Fry's book had an inauspicious start. Written in French, and intended to serve as an introduction to the Pellerin Collection in Paris (the most complete collection of Cézanne's work) L'Amour de l'Art was published in 1926 but without commercial or critical success. Fry translated the book into English and published it through Leonard and Virginia Woolf's Hogarth Press allowing it to reach a much wider public.

There is a strong degree of ambiguity about Cézanne's Autopsy leading some historians to have speculated on whether it could be an observational scene from rural medical practice, or even a version of the entombment of Christ. For Fry, however, this painting, like The Banquet and The Lazarus to which he compared it, was about an inner vision that bore no direct reference to actual models of real life or to models of antiquity. Cézanne had, according to Fry, "resigned himself to accepting the thing seen as the nucleus of crystallization in place of poetic inspiration". For Fry, Cézanne's lack of the "common gift of illustration" and his lack of an ability, such as that possessed by Rubens, to use his imagination to render "under any conditions of light and shade [to relate objects] within a credible space", was more than compensated for in his "inner visions" that showed "extraordinary dramatic force, a reckless daring born of intense inner conviction and above all a strangeness and unfamiliarity, which suggest something like hallucination".

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

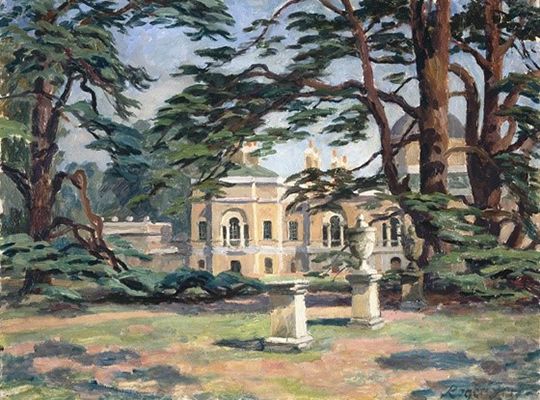

Chiswick House (1933)

Chiswick House in West London is pictured in the grounds of a garden featuring two stone plinths in the foreground, of which one is crowned with a classical vase. The setting seems to be one of late afternoon as dark shadows from the trees are being cast over the grounds. From the early 1920's Fry's painting had become more representational, as evidenced in his many landscapes of this period, especially those produced on his visits to his beloved Provence. Chiswick House thus represents a late lyricism in Fry's technique in which the subject matter overtakes, or at least matches, the paintings' formal qualities by focusing heavily on a sense of setting.

Speaking of his landscape paintings, Fry stated that they were "no difference [...] to his other subjects" and that "in general in painting I try to express the emotions that the contemplation of the form produces in me". His shift in emphasis to a more harmonious picture plane can be seen to coincide with his relationship with Helen Anrep, with whom, after many setbacks, he had finally found lasting love. Adding to the patchwork-like arrangement of naturalistic tones - greens, salmon pinks, purples and oranges - Fry makes no attempt to disguise or subdue his fluent brushwork. Chiswick House thus represents an artist having found inner peace in the later years of life.

Oil on canvas - Manchester Art Gallery

Biography of Roger Fry

Childhood and Education

Roger Eliot Fry was the son of the Judge, Edward Fry. He and his two sisters (Joan and Margery) were raised in a wealthy Quaker family in the Highgate area of North London. He was educated at Clifton College and King's College Cambridge where he joined the so-called "Cambridge Apostles". The Apostles were (are) a secret society (founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, the future First Bishop of Gibraltar) that met on Friday evenings to discuss topics such as truth, religion, art and ethics. The Apostles have included some of the most influential men in British public life including (John) Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, Lytton and James Strachey, GE Moore and Rupert Brooke. It was as an Apostle that Fry fostered his interest in art and several members of the Bloomsbury Group were former Apostles including Fry, Keynes, Woolf, Lytton Strachey and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson.

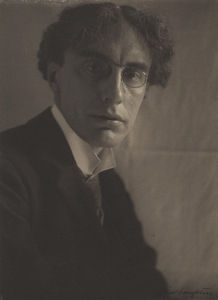

Graduating from Cambridge with a First in Natural Science, Fry trained as a painter under the tutorship of Francis Bate and by 1891 he was exhibiting his work at New English Art Club. Soon thereafter he headed for Paris and Rome to study art where he carved a niche for himself as a capable landscapist and portraitist.

Early Period

In 1896, Fry married the artist Helen Coombe with whom he parented two children, Pamela and Julian. He also took up a teaching post at the Slade School of Fine Art in London where he specialized in pre and early Renaissance painting. In 1899 he published his first book, Giovanni Bellini and, in 1903, he became, with Bernard Berenson and Herbert Horne, one of the founders of The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, promoted at the time as the first scholarly art history publication in Britain (Fry would publish more than 200 articles in the magazine over his lifetime). As his reputation grew, Fry wrote the introduction to an edition of Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses series, delivered to students of the Royal Academy, in 1905.

In 1906, having recently been turned down for the post of Slade Professor of Art at Oxford, Fry accepted an invitation from the banker, philanthropist and art collector John Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan to become Curator of European Painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Pierpont was the Museum's president). Fry accompanied Morgan on several buying trips to Europe and on a 1907 visit to Paris the two men attended a Paul Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne. Fry was overwhelmed by Cezanne's paintings and it marked the moment when he shifted his focus away from the Old Masters onto the Modernists. A year later he was settled back in London where he continued his association with the Museum as its "European Advisor" until a disagreement with Morgan led to his dismissal in 1910.

Between 1907 and 1910 Fry published several articles on the work of Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh arguing that they had collectively brought about a fusion of the structural sophistication of the classical artists and the explorations of color as advanced by the French Impressionists. Arguably his most influential work, "An Essay on Aesthetics", was published in New Quarterly, London, in 1909. In it Fry proposed that painting was duty-bound to express the human emotions rather than simply copy from the natural world. It was a view on art that went against the ideas of John Ruskin (hitherto England's most important critic) who's judgements on artworks were based on moral and aesthetic concerns. Drawing on the example of children, Fry argued that "if left to themselves [children never] copy what they see, never, as we say, 'draw from nature', but express, with a delightful freedom and sincerity, the mental images which make up their own imaginative lives". For Fry, therefore, art's very function was to stimulate the "imaginative life" of the artist and to do this the artist must be liberated from any kind of moral responsibility - as he put it, "[art] presents a life freed from the binding necessities of our actual existence".

Having by now "discovered" the Post-Impressionists, and helped promote the Neo-Impressionists (including the likes of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac), Fry organized an exhibition at the Grafton Galleries, London, in 1910 entitled Manet and the Post-Impressionists. It was, for most of the estimated 25,000 who attended, their first exposure to the works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse, and van Gogh (and possibly even Claude Monet who was better established by this time). The exhibition, which was followed by a second two years later, and the much more comprehensive Armory Show (the International Exhibition of Modern Art organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors) of New York in 1913, went a long way to build the reputations of Cézanne and the other Post-Impressionists. There were, however, repercussions for Fry whose support for this "unrefined" movement saw him effectively "demoted" from the rank of serious academic to the status of critic. Some of those billed in the catalogue as patrons of the exhibition even sought to disavow themselves of their initial support following the outcry over the exhibition.

The attack on Fry's critical judgement was merely compounded by his ongoing criticism of John Singer Sargent - he criticized the American's landscapes for lacking "the spirit, atmosphere, or poetry of place" (amongst other things) - who remained hugely popular with the public and generally respected amongst Academy members. Fry tried in vain to calm the backlash by publishing a piece in the influential New York weekly The Nation where he provided a list of people who supported the Post-Impressionists - one of which was Sargent. Sargent was so incensed at the inclusion of his name he published Too Much Money two open letters in The Nation through which he derided Fry and his support for the Post-Impressionists. The two men became sworn enemies (with Fry carrying his grudge even beyond Sargent's death by delivering a scathing account, in which he even denied Sargent the right to "be called an artist", of a retrospective of Sargent's work at the Royal Academy in 1926).

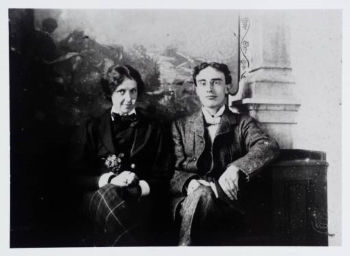

In 1910, Fry's wife, Helen, succumbed to serious mental illness and was sectioned, leading to a life spent in mental institutions. Fry took on parental responsibilities for their two children with the help of his sister, Joan. At the same time, he made the important acquaintance of Vanessa and Clive Bell (artist and art critic respectively) and through whom he was introduced to the Bloomsbury Group. Vanessa's sister was the author Virginia Woolf (who would write Fry's biography and in which said of him that "He had more knowledge and experience than the rest of [The Bloomsbury Group] put together"). In 1911 Fry began a short-lived affair with Vanessa whom he provided with warm care and support following a miscarriage. He was left heartbroken, however, when, in 1913, she set up home with the painter and designer Duncan Grant. Despite this personal set back, Fry founded the Omega Workshops with Vanessa and Grant as his co-directors. Coinciding with the birth of the Omega Workshops, Fry's paintings become more daring in their experimentation and he came to be regarded, if only for a few short years, as one of the most avant-garde artists working in Britain.

Mature Period

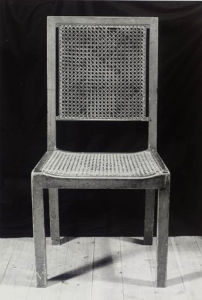

Bringing together artists including Grant, Bell, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Dora Carrington and Wyndham Lewis, the Omega Workshops Ltd. opened in July 1913 at 33 Fitzroy Square in Bloomsbury, central London. The premises functioned as a workshop, a gallery and, on Thursday nights, as a club (whose guests included the likes of George Bernard Shaw and W. B. Yeats). The public was invited to browse the furniture, fabrics, textiles, painted murals, stained glass and upholstery items in the signature Omega design. Fry personally produced an illustrated catalogue that ranged from individual products to a whole household decorative design scheme and the workshops were professionally run, employing a business manager, a caretaker and artist assistants. The links between the Arts and Crafts movement were obvious but Fry was not interested in social reform or railing against mass production (as William Morris had). Fry's goal was to blur the distinction between fine and decorative arts and was intent on bringing the bold colors and simplified forms of Post-Impressionism, Cubism and/or Fauvism to Omega designs. His vision was that artists could create utilitarian design objects but that they should do so anonymously; producing objects valued for their inherent beauty rather than for any idea of artistic reputation. Designs were thus marked only with the Workshop's symbol Ω (the Greek letter symbol Omega).

From 1915, The Omega Workshop extended its activities into fashion design and dressmaking. Its artists designed objects and engaged in some decorative work including the painting of some furniture items but the manufacture of products was generally undertaken outside of the workshop by professional craftsmen. J. Kallenborn & Sons of Stanhope Street, London made Marquetry furniture; Dryad Ltd of Leicester made tall cane seat chairs to Roger Fry's design; and printed linens were produced by a French company. Vanessa Bell began using Omega fabrics to produce dresses and the group even branched out into book design, publishing and theatre design. Indeed, in January 1918 the Omega Workshop was commissioned to produce sets and costumes for Israwl Zangwill's play Too Much Money and the director of the Russian Ballet, Sergei Diaghilev, approached Fry about a commission for stage designs and costumes. Though its influence on domestic design has proved lasting, and its objects highly prized by collectors, The Omega project was never a commercial success and closed in 1919.

Following a fleeting affair with the Welsh artist Nina Hamnet (aka: the "Queen of Bohemia") Fry entered a tragic relationship with a French woman called Josette Coatmellec. Fry met Josette in 1922 at a hypnosis clinic in Nancy where it is thought she was being treated for consumption. Fry returned to London but the two formed a close bond through an exchange of letters. The pair met again while Fry was on a visit to Paris in 1923 but by this time the Englishman was much in demand in the French capital and he could not devote as much time and attention as he would have liked towards Josette. She was left feeling neglected by Fry just as his feelings towards her were changing from fond affection to love. In the spring of 1924 the couple met in Paris once more with Fry showing off an African mask he had just acquired. Having again returned to London, Fry received a letter from Josette in which she accused him of baiting her with the mask and of directing all his loving attentions towards his art. He replied immediately, passionately refuting her accusations, but before the letter had reached its destination, Josette shot herself on a cliff at Le Havre facing England. Fry took her suicide very badly and attended the funeral, for which he designed the headstone. He also produced a long manuscript (written in French) which detailed their relationship.

Late Period

Woolf recorded in her diary that Fry felt that with Josette his "last chance of happiness had gone" and that he felt "fated and cursed" never to find lasting love. In 1926, however, Fry met his soulmate in Helen Maitland Anrep (the former wife of the Russian mosaicist Boris Anrep). According to the art historian Virginia Nicholson, Anrep was "warm hearted and argumentative" and as such "she fitted the romantic stereotype of the bohemian her clothes and easy going generosity". Indeed, Anrep became Fry's emotional anchor and they remained a couple for what remained of his life (though they never married). His new relationship would also see his art take on a more naturalistic tone.

In 1926, Fry wrote what some considered to be the definitive essay on Seurat. In the years between 1929 and 1934, he wrote and presented a series of twelve broadcasts on art and culture for BBC radio - he was a renowned public speaker with a mellifluous voice that George Bernard Shaw describes as one of only two he knew that were worth listening to for their own sake (the other the actor Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson) - arguing at length that African sculpture and Chinese ceramics were just as deserving of serious study as a Greek sculpture. In these later years he showed the reach of his cultural interests by translating the poems of, among others, Stéphane Mallarmé. In 1933, he achieved a lifetime ambition when he was appointed Slade Professor at Cambridge University.

Fry died suddenly in 1934 following complications after a fall at his London home. His passing left a deep scar on the Bloomsbury Group. Vanessa Bell took charge of decorating his casket before his ashes were laid to rest in the vault of the Kings College Chapel, Cambridge. Virginia Woolf took it upon herself write Fry's biography which was published in 1940.

The Legacy of Roger Fry

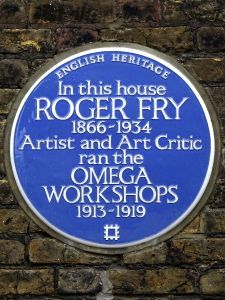

In May 2010 English Heritage commemorated Fry's contribution to the Country's cultural history by placing its iconic "Blue Plaque" at 33 Fitzroy Square, Bloomsbury, London, W1., site of the influential Omega Workshops. According to the English Heritage committee, "Fry may be said to have brought the avant-garde into British living rooms". Indeed, the art historian Kenneth Clark hailed him as "incomparably the greatest influence on taste since [John] Ruskin ... in so far as taste can be changed by one man, it was changed by Roger Fry". Meanwhile, the well-known English writer and Broadcaster, and member of the Blue Plaques Panel, Stephen Fry (no relation), added the following:

"Roger Fry was the most influential British art critic of the twentieth century. Without elitism, preciosity or pretension he helped open the British public's eyes to the new world of post-Impressionist art that heralded modernism in all its complexity and difficulty, but with all its rewards in energy, dynamism, impact and excitement. If only I could find a thread which might prove a familial connection between us: until then I'll just have to be content to share his great and glorious surname".

The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs marked his passing by commenting on "the man who in the past did most to establish [the magazine] and mould its character" which it attributed, amongst other things, to his attention to Chinese art which he shared with his Bloomsbury colleagues and which he helped locate within "a longer-term Western historiography of China and its culture(s), as well as within late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century discourses such as aestheticism, scientism and orientalism". But it is on the foundations of his promotion of the Post-Impressionists in Britain that Fry's legacy stands. Indeed, Fry did for Post-Impressionism what Felix Feneon did for Neo-Impressionism; what Guillaume Apollinaire did for the Cubists and other French avant-gardes; what Clement Greenberg did for Abstract Expressionism; and what Charles Saatchi did for the Young British Artists. His name joins thus a select list of the modern art world's most important influencers of taste.

Influences and Connections

![Virginia Woolf]() Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf- John Maynard Keynes

- Bernard Berenson

- Herbert Horne

-

![Vanessa Bell]() Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell -

![Duncan Grant]() Duncan Grant

Duncan Grant -

![Dora Carrington]() Dora Carrington

Dora Carrington -

![Wyndham Lewis]() Wyndham Lewis

Wyndham Lewis ![Henri Gaudier-Brzeska]() Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

- Virginia Wolfe

- Kenneth Clark

- E. M. Forster

- Bernard Berenson

- Herbert Horne

-

![The Bloomsbury Group Artists]() The Bloomsbury Group Artists

The Bloomsbury Group Artists - Omega Workshop

Useful Resources on Roger Fry

- "Fry, Roger" Oxford Dictionary of Art and ArtistsOur PickBy Ian Chilvers

- Roger Fry and the beginnings of formalist art criticismOur PickBy Jacqueline V. Falkenheim

- Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939Our PickBy Virginia Nicholson

- Roger Fry, Art and LifeOur PickBy Frances Spalding

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI