Summary of Surrealism

The Surrealists sought to channel the unconscious as a means to unlock the power of the imagination. Disdaining rationalism and literary realism, and powerfully influenced by psychoanalysis, the Surrealists believed the rational mind repressed the power of the imagination, weighing it down with taboos. Influenced also by Karl Marx, they hoped that the psyche had the power to reveal the contradictions in the everyday world and spur on revolution. Their emphasis on the power of personal imagination puts them in the tradition of Romanticism, but unlike their forebears, they believed that revelations could be found on the street and in everyday life. The Surrealist impulse to tap the unconscious mind, and their interests in myth and primitivism, went on to shape many later movements, and the style remains influential to this today.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- André Breton defined Surrealism as "psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express - verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner - the actual functioning of thought." What Breton is proposing is that artists bypass reason and rationality by accessing their unconscious mind. In practice, these techniques became known as automatism or automatic writing, which allowed artists to forgo conscious thought and embrace chance when creating art.

- The work of Sigmund Freud was profoundly influential for Surrealists, particularly his book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). Freud legitimized the importance of dreams and the unconscious as valid revelations of human emotion and desires; his exposure of the complex and repressed inner worlds of sexuality, desire, and violence provided a theoretical basis for much of Surrealism.

- Surrealist imagery is probably the most recognizable element of the movement, yet it is also the most elusive to categorize and define. Each artist relied on their own recurring motifs arisen through their dreams or/and unconscious mind. At its basic, the imagery is outlandish, perplexing, and even uncanny, as it is meant to jolt the viewer out of their comforting assumptions. Nature, however, is the most frequent imagery: Max Ernst was obsessed with birds and had a bird alter ego, Salvador Dalí's works often include ants or eggs, and Joan Miró relied strongly on vague biomorphic imagery.

Overview of Surrealism

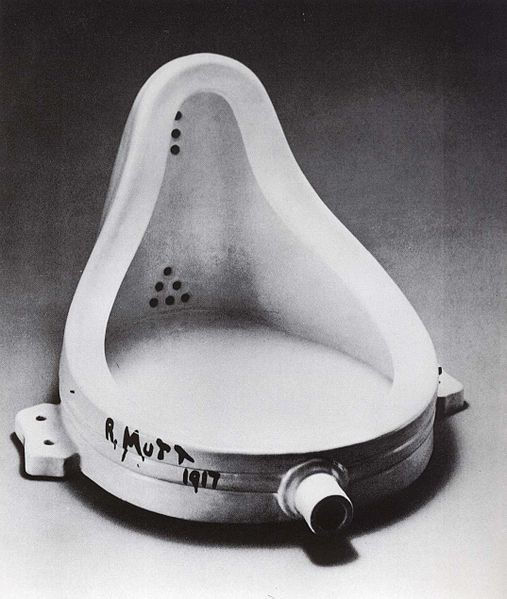

Building upon the anti-rationalism of Dada, the Surrealists made powerful art and offered a new direction for exploration, as Max Ernst said: "creativity is that marvelous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition."

Artworks and Artists of Surrealism

Carnival of Harlequin (1924-25)

Miró created elaborate, fantastical spaces in his paintings that are an excellent example of Surrealism in their reliance on dream-like imagery and their use of biomorphism. Biomorphic shapes are those that resemble organic beings but that are hard to identify as any specific thing; the shapes seem to self-generate, morph, and dance on the canvas. While there is the suggestion of a believable three-dimensional space in Carnaval d'Arlequin, the playful shapes are arranged with an all-over quality that is common to many of Miró's works during his Surrealist period, and that would eventually lead him to further abstraction. Miró was especially known for his use of automatic writing techniques in the creation of his works, particularly doodling or automatic drawing, which is how he began many of his canvases. He is best known for his works such as this that depict chaotic yet lighthearted interior scenes, taking his influence from Dutch 17th-century interiors.

Oil on canvas - Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

The Human Condition (1933)

The iconic and enigmatic René Magritte's works tend to be intellectual, often dealing with visual puns and the relation between the representation of something and the thing itself. In The Human Condition a canvas sits on an easel before a curtained window and reproduces exactly the scene outside the window that would be behind the canvas, thus the image on the easel in a sense becomes the scene, not just a reproduction of the landscape. There is in effect no difference between the two as both are fabrications of the artist. The hyperrealist painting style often used by Surrealists makes the odd setup seem dreamlike.

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

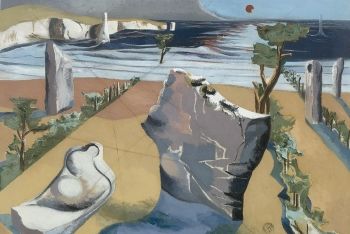

Mama, Papa is Wounded! (1927)

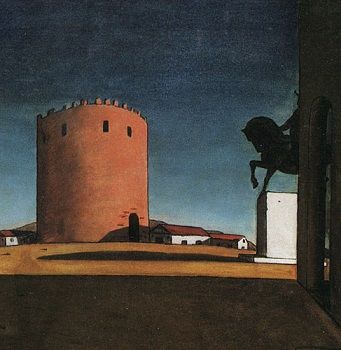

The most pivotal moment for Tanguy in his decision to become a painter was his sighting of a canvas by Giorgio de Chirico in a shop window in 1923. The next year, Tanguy, the poet Jacques Prévert, and the actor and screenwriter Marcel Duhamel moved into a house that was to become a gathering place for the Surrealists, a movement he became interested in after reading the periodical La Révolution surréaliste. André Breton welcomed him into the group in 1925. Tanguy was inspired by the biomorphic forms of Jean Arp, Ernst, and Miró, quickly developing his own vocabulary of amoeba-like shapes that populate arid, mysterious settings, no doubt influenced by his youthful travels to Argentina, Brazil, and Tunisia. Despite his lack of formal training, Tanguy's mature style emerged by 1927, characterized by deserted landscapes littered with fantastical rocklike objects painted with a precise illusionism. The works usually have an overcast sky with a view thatseems to stretch endlessly.

Mama, Papa is Wounded depicts Tanguy's most common subject matter of war. The work is painted in a hyperrealist style with his distinctive limited color palette, both of which create a sense of dream-like reality. Tanguy often found the titles of works while looking through psychiatric case histories for compelling statements by patients. Given that, it is difficult to know if this work is relevant to his own family history as he claimed to have imagined the painting in its entirety before he began it. His brother was killed in World War I and the bleakness of the landscape may refer generally to losses suffered in the war by thousands of French families. De Chirico's influence on Tanguy's work is obvious here in his use of falling shadows and a classical torso in the landscape.

Oil on Canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Accommodations of Desire (1929)

Painted in the summer of 1929 just after Dalí went to Paris for his first Surrealist exhibition, The Accommodations of Desire is a prime example of Dalí's ability to render his vivid and bizarre dreams with seemingly journalistic accuracy. He developed the paranoid-critical method, which involved systematic irrational thought and self-induced paranoia as a way to access his unconscious. He referred to the resulting works as "hand-painted dream photographs" because of their realism coupled with their eerie dream quality. The narrative of this work stems from Dalí's anxieties over his affair with Gala Eluard, wife of artist Paul Eluard. The lumpish white "pebbles" depict his insecurities about his future with Gala, circling around the concepts of terror and decay. While The Accommodations of Desire is an exposé of Dalí's deepest fears, it combines his typical hyper-realistic painting style with more experimental collage techniques. The lion heads are glued onto the canvas, and are believed to have been cut from a children's book.

Oil and cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Palace at 4 a.m. (1932)

Giacometti was one of the few Surrealists who focused on sculpture. The Palace at 4 a.m. is a delicate construction that was inspired by his obsession with a lover named Denise the previous year. Of the affair he said, "a period of six months passed in the presence of a woman who, concentrating all life in herself, transported my every moment into a state of enchantment. We constructed a fantastical palace in the night - a very fragile palace of matches. At the least false movement a whole section would collapse. We always began it again." In 1933, he told Breton that he was incapable of making anything that did not have something to do with her.

The work includes representations or symbols of his love interest as well as perhaps of his mother. Other imagery, such as the bird, is less easy to interpret. Thus, the work is characterized by its bizarre juxtaposition of objects and a title that is seemingly unrelated to the constructed scene, giving the piece an undercurrent of mystery and tension as if something frightening is about to occur. The work, in its child-like simplicity, captures the fragility of memory and desire. Giacometti's postwar interest in Existentialism is already evident here in how he represents the isolation of the various figures.

Wood, glass, wire, and string - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Battle of Fishes (1926)

Masson was one of the most enthusiastic followers of Breton's automatic writing, having begun his own independent experiments in the early 1920s. He would often produce art under exacting conditions, using drugs, going without sleep, or sustenance in order to relax conscious control of his art making so that he could access his unconscious. Masson, along with his neighbors Joan Miró, Antonin Artuad, and others would sometimes experiment together. He is best known for his use of sand. In an effort to introduce chance into his works, he would throw glue or gesso onto a canvas and then sand. His oil paintings were made based on the resulting shapes.

Battle of the Fishes perhaps references his experiences in WWI. He signed up to fight and after three years, was seriously injured, taking months to recover in an army hospital and spending time in a psychiatric facility. He was unable for many years to speak of the things he witnessed as a soldier, but his art consistently depicts massacres, bizarre confrontations, rape, and dismemberment. Masson himself observed that male figures in his art rarely escape unharmed. Battle of Fishes has subdued color, but the fish seem involved in a vicious battle to the death with their razor-like teeth and spilled blood. Masson believed that the use of chance in art would reveal the sadism of all creatures - an idea that he could only reveal in his art.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Object (1936)

Oppenheim was one of the few women Surrealists whose work was exhibited with the group. Like Giacometti she worked primarily with objects. This work, also known under the title Luncheon in Fur, with its unsettling juxtaposition of a domestic object and animality, is a quintessential example of Surrealist ideas. The artist makes strange a teacup, saucer, and spoon purchased at typical department store - objects that were familiar are made disturbingly off-putting as the viewer must imagine drinking tea from a fur-covered cup.

Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Barbarians (1937)

Max Ernst was known for his automatic writing techniques including frottage, grattage, and collage. Here he uses grattage, which requires taking a painted canvas, placing it on a textured surface, and scraping off paint. The method introduces elements of chance and unpredictability to the work as the artist is forced to release some control of the creative process. The grattaged canvas was then used by Ernst as inspiration for further imagery. The Barbarians is typically Surrealist as it is fraught with bizarre juxtapositions, mysterious figures, and dream-inspired symbols. The bird imagery is one of the staples of Ernst's work - he experienced a childhood trauma related to the death of his pet bird and as an adult developed a bird alter ego named Loplop.

Oil on wood with painted wood elements - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mannequin (1938)

Mannequin depicts André Masson's mannequin at the Exposition International du Surrealisme, Galerie des Beaux-Arts, in Paris 1938. Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Maurice Henry, and others also designed these weird mannequins to fill a room with uncanny female forms that looked both monstrous and sexually alluring. Man Ray photographed them all as discreet characters, of which this is one example. He repeatedly photographed his assistant, artist Lee Miller, and many other women, both living and inanimate. Like Hans Bellmer, an artist peripherally associated with the group, Ray was obsessed with the female form as the perfect embodiment of male desire, and sought to capture it formally in fantastical ways. Man Ray also pioneered many photographic techniques, including rayographs, named after himself, that incorporate elements of chance and in which subjects appear to glow in dream-like silver auras.

Assemblage of wood, oil, metal, board on board, with artist's frame - National Gallery of Australia

Birthday (1942)

Birthday is a self-portrait that Dorothea Tanning painted to commemorate her 30th birthday. Viewed up close, one notices the infinite rooms recessing into the background, symbolizing Tanning's unconscious mind. Many Surrealists felt architectural imagery was well-suited to expressing notions of a labyrinthine self that changes and expands over time; Birthday is one of the best examples of this. Also notable is the gargoyle at the subject's feet. Tanning said this was her rendition of a lemur, which has been associated with death spirits. Tanning juxtaposed natural imagery, like the skirt made of roots, against objects representing high culture, like fancy apparel and interior design, to pay homage to culture as well as to express nature and wilderness as a feminine construct.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Beginnings of Surrealism

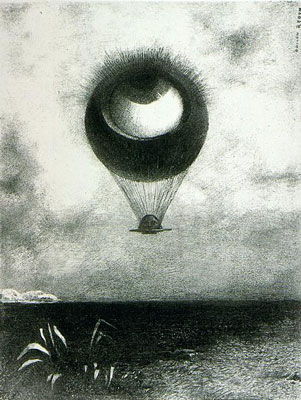

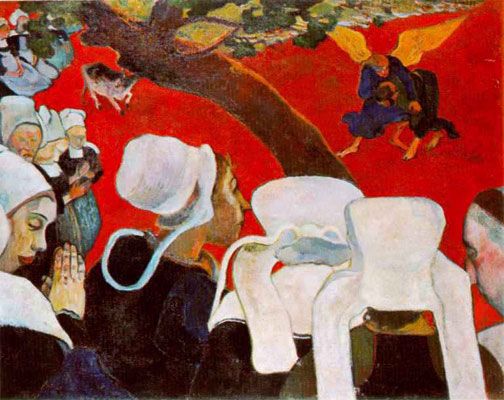

Surrealism grew out of the Dada movement, which was also in rebellion against middle-class complacency. Artistic influences, however, came from many different sources. The most immediate influence for several of the Surrealists was Giorgio de Chirico, their contemporary who, like them, used bizarre imagery with unsettling juxtapositions (and his Metaphysical Painting movement). They were also drawn to artists from the recent past who were interested in primitivism, the naive, or fantastical imagery, such as Gustave Moreau, Arnold Bocklin, Odilon Redon, and Henri Rousseau. Even artists from as far back as the Renaissance, such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo and Hieronymous Bosch, provided inspiration in so far as these artists were not overly concerned with aesthetic issues involving line and color, but instead felt compelled to create what Surrealists thought of as the "real."

The Surrealist movement began as a literary group strongly allied to Dada, emerging in the wake of the collapse of Dada in Paris, when André Breton's eagerness to bring purpose to Dada clashed with Tristan Tzara's anti-authoritarianism. Breton, who is occasionally described as the 'Pope' of Surrealism, officially founded the movement in 1924 when he wrote "The Surrealist Manifesto." However, the term "surrealism," was first coined in 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire when he used it in program notes for the ballet Parade, written by Pablo Picasso, Leonide Massine, Jean Cocteau, and Erik Satie.

Around the same time that Breton published his inaugural manifesto, the group began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste, which was largely focused on writing, but also included art reproductions by artists such as de Chirico, Ernst, André Masson, and Man Ray. Publication continued until 1929.

The Bureau for Surrealist Research or Centrale Surréaliste was also established in Paris in 1924. This was a loosely affiliated group of writers and artists who met and conducted interviews to "gather all the information possible related to forms that might express the unconscious activity of the mind." Headed by Breton, the Bureau created a dual archive: one that collected dream imagery and one that collected material related to social life. At least two people manned the office each day - one to greet visitors and the other to write down the observations and comments of the visitors that then became part of the archive. In January of 1925, the Bureau officially published its revolutionary intent that was signed by 27 people, including Breton, Ernst, and Masson.

Surrealism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Surrealism shared much of the anti-rationalism of Dada, the movement out of which it grew. The original Parisian Surrealists used art as a reprieve from violent political situations and to address the unease they felt about the world's uncertainties. By employing fantasy and dream imagery, artists generated creative works in a variety of media that exposed their inner minds in eccentric, symbolic ways, uncovering anxieties and treating them analytically through visual means.

Surrealist Paintings

There were two styles or methods that distinguished Surrealist painting. Artists such as Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte painted in a hyper-realistic style in which objects were depicted in crisp detail and with the illusion of three-dimensionality, emphasizing their dream-like quality. The color in these works was often either saturated (Dalí) or monochromatic (Tanguy), both choices conveying a dream state.

Several Surrealists also relied heavily on automatism or automatic writing as a way to tap into the unconscious mind. Artists such as Joan Miró and Max Ernst used various techniques to create unlikely and often outlandish imagery including collage, doodling, frottage, decalcomania, and grattage. Artists such as Hans Arp also created collages as stand-alone works.

Hyperrealism and automatism were not mutually exclusive. Miro, for example, often used both methods in one work. In either case, however the subject matter was arrived at or depicted, it was always bizarre - meant to disturb and baffle.

Surrealist Objects and Sculptures

Breton felt that the object had been in a state of crisis since the early-19th century and thought this impasse could be overcome if the object in all its strangeness could be seen as if for the first time. The strategy was not to make Surreal objects for the sake of shocking the middle class a la Dada but to make objects "surreal" by what he called dépayesment or estrangement. The goal was the displacement of the object, removing it from its expected context, "defamilarizing" it. Once the object was removed from its normal circumstances, it could be seen without the mask of its cultural context. These incongruous combinations of objects were also thought to reveal the fraught sexual and psychological forces hidden beneath the surface of reality.

A limited number of Surrealists are known for their three-dimensional work. Arp, who began as part of the Dada movement, was known for his biomorphic objects. Oppenheim's pieces were bizarre combinations that removed familiar objects from their everyday context, while Giacometti's were more traditional sculptural forms, many of which were human-insect hybrid figures. Dalí, less known for his 3D work, did produce some interesting installations, particularly, Rainy Taxi (1938), which was an automobile with mannequins and a series of pipes that created "rain" in the car's interior.

Surrealist Photography

Photography, because of the ease with which it allowed artists to produce uncanny imagery, occupied a central role in Surrealism. Artists such as Man Ray and Maurice Tabard used the medium to explore automatic writing, using techniques such as double exposure, combination printing, montage, and solarization, the latter of which eschewed the camera altogether. Other photographers used rotation or distortion to render bizarre images.

The Surrealists also appreciated the prosaic photograph removed from its mundane context and seen through the lens of Surrealist sensibility. Vernacular snapshots, police photographs, movie stills, and documentary photographs all were published in Surrealist journals like La Révolution surréaliste and Minotaure, totally disconnected from their original purposes. The Surrealists, for example, were enthusiastic about Eugène Atget's photographs of Paris. Published in 1926 in La Révolution surréaliste at the prompting of his neighbor, Man Ray, Atget's imagery of a quickly vanishing Paris was understood as impulsive visions. Atget's photographs of empty streets and shop windows recalled the Surrealist's own vision of Paris as a "dream capital."

Surrealist Film

Surrealism was the first artistic movement to experiment with cinema in part because it offered more opportunity than theatre to create the bizarre or the unreal. The first film characterized as Surrealist was the 1924 Entr'acte, a 22-minute, silent film, written by Rene Clair and Francis Picabia, and directed by Clair. But, the most famous Surrealist filmmaker was of course Luis Buñuel. Working with Dalí, Buñuel made the classic films Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L'Age d'Or (1930), both of which were characterized by narrative disjunction and their peculiar, sometimes disturbing imagery. In the 1930s Joseph Cornell produced surrealist films in the United States, such as Rose Hobart (1936). Salvador Dalí designed a dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945).

The Rise and Decline of Surrealism

Though Surrealism originated in France, strains of it can be identified in art throughout the world. Particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, many artists were swept into its orbit as increasing political upheaval and a second global war encouraged fears that human civilization was in a state of crisis and collapse. The emigration of many Surrealists to the Americas during WWII spread their ideas further. Following the war, however, the group's ideas were challenged by the rise of Existentialism, which, while also celebrating individualism, was more rationally based than Surrealism. In the arts, the Abstract Expressionists incorporated Surrealist ideas and usurped their dominance by pioneering new techniques for representing the unconscious. Breton became increasingly interested in revolutionary political activism as the movement's primary goal. The result was the dispersal of the original movement into smaller factions of artists. The Bretonians, such as Roberto Matta, believed that art was inherently political. Others, like Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, and Dorothea Tanning, remained in America to separate from Breton. Salvador Dalí, likewise, retreated to Spain, believing in the centrality of the individual in art.

Later Developments - After Surrealism

Abstract Expressionism

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art in New York staged an exhibition entitled Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, and many American artists were powerfully impressed by it. Some, such as Jackson Pollock, began to experiment with automatism, and with imagery that seemed to derive from the unconscious - experiments which would later lead to his "drip" paintings. Robert Motherwell, similarly, is said to have been "stuck between the two worlds" of abstraction and automatism.

Largely because of political upheaval in Europe, New York rather than Paris became the emergent center of a new vanguard, one that favored tapping the unconscious through abstraction as opposed to the "hand-painted dreams" of Salvador Dalí. Peggy Guggenheim's 1942 exhibition of Surrealist-influenced artists (Rothko, Gottlieb, Motherwell, Baziotes, Hoffman, Still, and Pollock) alongside European artists Miró, Klee, and Masson, underscores the speed with which Surrealist concepts spread through the New York art community.

Feminism and Women Surrealists

The Surrealists have often been depicted as a tightly knit group of men, and their art often envisioned women as wild "others" to the cultured, rational world. Work by feminist art historians has since corrected this impression, not only highlighting the number of women Surrealists who were active in the group, particularly in the 1930s, but also analyzing the gender stereotypes at work in much Surrealist art. Feminist art critics, such as Dawn Ades, Mary Ann Caws, and Whitney Chadwick, have devoted several books and exhibitions to this subject.

While most of the male Surrealists, especially Man Ray, Magritte, and Dalí, repeatedly focused on and/or distorted the female form and depicted women as muses, much in the way that male artists had for centuries, female Surrealists such as Claude Cahun, Lee Miller, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning, sought to address the problematic adoption of Freudian psychoanalysis that often cast women as monstrous and lesser. Thus, many female Surrealists experimented with cross-dressing and depicted themselves as animals or mythic creatures.

British Surrealism

Interestingly, many notable female Surrealists were British. Examples include Eileen Agar, Ithell Colquhoun, Edith Rimmington, and Emmy Bridgwater. Particular to the British interpretation of Surrealist ideology was an ongoing exploration of human relations with their surrounding natural environment and most prominently, with the sea. Alongside Agar, Paul Nash developed an interest in the object trouvé, usually in the form of items collected from the beach. The focus on the border where land meets the sea, and where rocks anthropomorphically resemble people struck a cord with British identity and more generally, with Surrealist principles of reconciling and uniting opposites.

The International Surrealist Exhibition (1936) held in London was a particular catalyst for many British artists. Headed by Roland Penrose and Herbert Read, the movement thrived in Britain, creating the international icons Leonora Carrington and Lee Miller, and also spurring on the practice of another important circle of artists surrounding Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore. Overall, the privileging of an eccentric imagination and essential rejection of standardized and rational modes of doing things resonated well from the outset. This golden period for art in general in the UK, and more specifically the legacies of British Surrealism continue to influence the country’s art practice today.

Useful Resources on Surrealism

-

![Salvador Dalí - Masters of the Modern Era]() 659k viewsSalvador Dalí - Masters of the Modern EraOur PickBy British art critic Alastair Sooke

659k viewsSalvador Dalí - Masters of the Modern EraOur PickBy British art critic Alastair Sooke -

![René Magritte]() 1.1M viewsRené MagritteOur Pick"What Is The Treachery of Images?" episode of The Nerdwriter

1.1M viewsRené MagritteOur Pick"What Is The Treachery of Images?" episode of The Nerdwriter -

![Max Ernst & The Surrealist Revolution]() 57k viewsMax Ernst & The Surrealist RevolutionGood 1991 overview of Ernst's work and the overall aims of Surrealism

57k viewsMax Ernst & The Surrealist RevolutionGood 1991 overview of Ernst's work and the overall aims of Surrealism -

![Yves Tanguy & Kay Sage]() 0 viewsYves Tanguy & Kay SageThe artist couple and their place in Surrealism

0 viewsYves Tanguy & Kay SageThe artist couple and their place in Surrealism -

![Alberto Giacometti]() 51k viewsAlberto GiacomettiGeneral overview of career

51k viewsAlberto GiacomettiGeneral overview of career -

![Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí's <i>Un Chien Andalou</i>]() 0 viewsLuis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí's Un Chien AndalouOur PickThe seminal short film that launched their careers

0 viewsLuis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí's Un Chien AndalouOur PickThe seminal short film that launched their careers

-

!["Dada and Surrealism"]() 107k views"Dada and Surrealism"Lecture by The Dalí Museum Curator of Education Peter Tush

107k views"Dada and Surrealism"Lecture by The Dalí Museum Curator of Education Peter Tush -

![Surrealism Lesson Series]() 11k viewsSurrealism Lesson Series16 short lectures on Surrealism highlighting many less famous Surrealist. Narated by writer, publisher and artist Adam McLean

11k viewsSurrealism Lesson Series16 short lectures on Surrealism highlighting many less famous Surrealist. Narated by writer, publisher and artist Adam McLean