Summary of Dada and Surrealist Photography

In post-WWI Germany and Paris, a ground-breaking practice of photography emerged, inspired by Dada's improvisational practices and the Surrealist's foray into the unconscious, dream, and fantasy realms. Whereas photography had been widely used as a tool to document reality, artists began to work with the camera and progressive techniques to create images jarringly detached from photography's original uses. These visuals oftentimes challenged the viewer's perceptions with a strong basis in conceptualism, conjuring the uncanny, ethereal, or unordinary. Other times, they emphasized the artist's intent, by presenting familiar images unlatched from their usual context, inviting new perspectives of the ordinary. This practice would spread to America and become a forebear to the decades-long exploration of the possibilities of the photographic image that remains common in today's art world.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Artists during this time began to explore revolutionary photographic techniques, born from the Surrealist impetus toward discovering affinities in fragments of imagery. This included photomontage, collage, post-production manipulation of photos, staging, and the photogram.

- Many of these photographers focused on presenting images grounded in reality but which challenged perception, or tricked the eye of the viewer into seeing what lay beneath, forcing a sense of distorted reality. These pictures, upon first glance might be deemed familiar, but would instantly require a double take.

- Much of the photography of this time evolved Surrealism's combination of imagery and text in order to carry the artist's intention through to the viewer. By borrowing methods from the magazine and newspaper industry, these artists were turning their work into "advertisements" of the individual artist's mind.

- Many art journals were birthed during this time, a perfect platform for printing these photographs, and a way to mass distribute these works of art to a populous which might otherwise not have access to them.

Important Photographs and Artists of Dada and Surrealist Photography

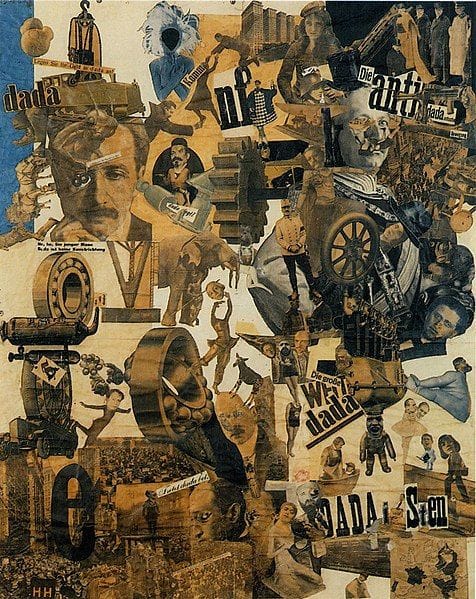

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany

Though one of Höch's earliest works, this ambitious collage is unusual within her canon for being particularly large; it measures 35 x 57 inches. The piece was exhibited in the First International Dada Fair, which took place in Berlin in 1920, and it was reportedly one of the most popular pieces in the show. In the top right corner Höch pasted together images of "anti-Dada" figures of the Weimar government and representatives of the old empire. Elsewhere in the collage, known proponents of Dada, such as Raoul Hausmann, are arranged in contrast to these establishment figures.

The effect is initially one of visual confusion, and yet a kind of nonsense-narrative begins to develop with sustained attention. One figure is transformed into something else by the addition of a de-contextualised newspaper clipping, such as the Kaiser's iconic moustache replaced by a pair of upside-down wrestlers. The work encapsulates the eclecticism and eccentricities of Dadaism, but also makes a pointed political statement against the staid establishment; it is a carefully crafted homage to anarchistic opposition.

The piece expertly illustrates the Surrealist use of photomontage along with the technique of taking words and images from the established press to create a fresh, subversive statement that was highly innovative for the time.

Photomontage

Dust Breeding

This is an important example of early Surrealist photography, crossing the line between Dada and Surrealism in the early 1920s. It is a photograph taken by Man Ray of Marcel Duchamp's masterpiece The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923) after it had sat for three years gathering dust in Duchamp's studio. Dust Breeding is an important early example of collaboration in Surrealism; where two artists utilized the combination of imagery to defy literal presentation and concoct an all-together new piece in which one media interrogates and challenges another.

Although Dust Breeding is literally a close-up photograph of a dusty surface where the graphic lines of Duchamp's masterpiece peek through just visible, the resulting effort resembles an aerial photograph. When the work was published for the first time (in the early Surrealist journal Litterature), it was humorously captioned View from an Aeroplane. This points to Man Ray's aim of using photography in combination with language to trick the viewer's eye and to distort the viewer's powers of perception through psychic suggestion. It was one of the few photographs published in a Surrealist journal before 1924, hinting at its importance as an early example of Surrealist photography.

Contemporary photographer Sophie Ristelhueber was strongly influenced by Man Ray's photographs and by this work in particular. She argues that, "the constant shift between the infinitely big and the infinitely small may disorientate the spectator. But it is a good illustration of our relationship to the world: we have at our disposal modern techniques for seeing everything, apprehending everything, yet we see nothing."

Silver gelatin print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Le Violon d'Ingres (Ingres's Violin)

Le Violon d'Ingres is one of the best-known images in modern art. To create this work, Man Ray took a photograph of one of his favorite models, Kiki, and made her pose resemble a painting by Ingres. He subsequently painted two "F" symbols copied from the body of a violin onto the print, before re-photographing it. This is a powerful example of post-production manipulation being used to create a Surrealist effect in photography.

Man Ray's manipulation gives the work a number of layers of meaning. By re-photographing the print, Man Ray elides the original image with his manipulation of it, resulting in the woman's body being inseparable from the violin-like figurations on it. This confuses the viewer's understanding of the image: are those black marks painted or tattooed directly onto her skin or are we in fact looking at a woman with holes in her back like the body of a violin? Such confusion points to the inherent instability of the photographic image so often explored by the Surrealist photographers.

Art historian David Bate also argues that this image is a key example of the Surrealist disruption of the photographic issues of mimesis and the signifier/signified: "The signifying plane of the photograph itself has been disrupted [...]. No longer purely mimetic, the photograph confuses the usual status and conventions of a photographic image with respect to reality. It introduces fantasy."

Silver gelatin print - Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Storefront avenue des Gobelins

This is one of Atget's more playful images that he created toward the end of his life, though prototypical of his iconic, continual series of mannequins in storefront windows. Fashion figures pose in a display case like human surrogates, showcasing the trendy fashions of the day. Their exaggerated gestures make for an odd tableau that is further complicated by various reflections in the window. Tree branches, a building opposite the storefront, and Atget's own leg overlap the scene to create new shapes and references. The treatment of light resulted from a masterful technique. The intermingling spaces, objects, and tones of black simultaneously merge and disjoint the photograph. This blend of imagery, between fiction and reality, conjures the dreamy, fragmentary realms in which the viewer's perspective is challenged by that which is true and that which is imagined. Because of this, Atget's work was championed by the Surrealists and adopted as part of the movement.

Matte albumen print - The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

Je ne vois pas la femme cachee dans la foret

This work by René Magritte furthered the ideas of collage and photomontage by combining painting and photography in a unique way to inform a conceptual idea. It features a central painting of a nude woman on a black background, with the words in French, "I do not see the woman hidden in the forest." This is surrounded by a series of photographs of key male members of the Surrealist movement, all wearing suits and ties and all with their eyes closed.

The implication is that, for men (and for the Surrealists in particular), women did not exist as real people, but simply as fantasy objects. Rather than "see" them for their human qualities, men choose to close their eyes and allow them to enter their dreams rather than their waking lives. This is emphasized by the fact that the woman is painted, a creation from the imagination, as opposed to the men who are depicted in their photographic reality.

Art historian Robert James Belton argues that "surrounded there by Surrealists with closed eyes, she signifies precisely that her adorers were indeed blind to any but their own subjective inner realities." This suggests an element of self-reflexive understanding that is very important for appreciating the Surrealist movement.

Mixed media collage

Plate no.1 from Aveux non Avenus

This plate from Claude Cahun's 1930 novel Aveux non Avenus (translated as "Confessions" or "Disavowals") shows several pairs of hands holding an eye, a magnifying glass or mirror, and a globe. The plates in this book are important examples of the use of photomontage in Surrealist photography, where disparate elements are juxtaposed to create an unsettling or uncanny effect. This work is representative of the phase of Cahun's career when she was most engaged in the ideas of Surrealism. Interestingly, the image is signed "Moore," referring to Claude Cahun's lifelong partner Marcel Moore (born Suzanne Malherbe). This dual ascribing of authorship points to the importance of collaboration for many Surrealist photographers such as Cahun.

Photographs and photographic images are at the heart of this text, a collection of prose poems, poem-essays and photo-collages, pointing to the key alignment of photography and literature within the Surrealist movement. Cahun's photographs suggest that each element should not be considered in isolation, but as part of a wider interdisciplinary practice that is typical of many Surrealist photographers.

This plate accompanies her opening chapter, which starts as follows with a description of taking a photograph:

"The invisible adventure.

The lens tracks the eyes, the mouth, the wrinkles skin deep... the expression on the face is fierce, sometimes tragic. And then calm - a knowing calm, worked on, flashy. A professional smile - and voilà!

The hand-held mirror reappears, and the rouge and the eye shadow. A beat. Full stop. New paragraph."

In her photographs, and in this quotation in particular, Cahun draws attention to photography's artifice, its ability to trick despite its apparently scientific "honesty." The hand-held mirror has only been held away from the face for a minute, during the moment of capture, before it reappears for the stereotypically feminine task of self-inspection. Cahun, along with other women who take photographic self-portraits, both confirms and undermines stereotypical images of femininity, drawing attention to their prevalence and self-perpetuation while simultaneously highlighting their subjectivity, multiplicity, and artifice.

Photomontage

Distortion #51

Although Kertesz had been working with photography since the 1910s, his Distortions series in the 1930s was one of his most significant and effective forays into Surrealist photography. Commissioned by Le Sourire, a risqué magazine, the images combined sexuality and dream-like metamorphosis through Kertesz's capturing of a warped reality.

Kertesz took this photograph using a funhouse mirror in a Paris fairground. The image captures some of the disorienting and out-of-body sensations caused by the house of mirrors, where one's body is reflected in unexpected ways and from strange angles, developing the Surrealist aim of documenting and creating alternative realities and normalities.

Although the images in this series are of nude women, in many examples, such as Distortion #51, the figure's nudity is both sexual and anti-sexual due to deformation. The woman, with her exaggerated screaming mouth, is both erotic and highly disturbing; with a nightmarish quality that connotes the Surrealist interest in dreams. As art historian Christian Bouqueret argues, "Throughout the series, the female model is continually subjected to deformation, hypertrophy and anamorphosis. She may be inflated into a lewd monster, or she may dwindle into a mere palpitation that seeks to reinvent the nature of movement - a grotesque gasp of breath."

Gelatin silver print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Doll

Hans Bellmer's photographs of dolls are perhaps some of the best-known Surrealist photographs. However, Bellmer was not closely connected with the group until 1938, when the changing political situation in Germany forced him to flee to Paris, where Andre Breton welcomed him. Consequently, he made much of his work in relative artistic isolation, associating with the Surrealists only from a distance.

Nevertheless, his work accords closely with Surrealist principles. Initially, he started to make sexualized sculptures of dolls inspired by Jacques Offenbach's (1819-1880) final opera The Tales of Hoffmann, where the protagonist falls in love with a life-size doll. He soon started to photograph the dolls, and his photographs are now considered artworks in their own right. The doll is a key figuration in Surrealist art, and particularly in Surrealist photography. Thinkers who were to have an important influence on the Surrealists, such as the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, have written extensively about dolls and how they represent the uncanny: uncomfortably similar to a human but also uncomfortably unlike one.

Bellmer complicates this discourse by sexualizing and dismembering his dolls. The dolls are a symbol of erotic desire but also of erotic violence. By committing a violent act on a figure that is already inanimate ("killing" the doll through hanging and dismemberment), Bellmer makes the relationship between person and object even more fraught psychologically. His work points deeply toward the Surrealist impulse to manifest unconscious drives, unapologetically, through artwork.

Silver gelatin print - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Father Ubu

Dora Maar is often better known for being the muse and lover of Pablo Picasso. However, she was, first and foremost, a talented artist in her own right who took to photography for both artistic and political reasons. Some of her earliest work (before she became associated with the Surrealists) was a series of photographic portraits of the poor and disenfranchised in Barcelona, Paris and London. These depictions of the pitiful condition of many members of society align with her strong leftist political views.

However, Maar became increasingly involved in the Surrealist movement, drawn to their political statements and to their use of the fantastical to propose alternative ways of being and thinking. She shared a studio with Surrealist photographer Brassai and began experimenting with new subjects and techniques. One of her most famous series of works are photographs of an armadillo fetus. Maar's image points to a key facet of Surrealist photography: photographs did not have to be heavily manipulated for the subjects to emerge unrecognizable. Instead, Maar used traditional photography techniques to find something extraordinary in the everyday. She used this photograph to show that the monstrous and the obscene could occupy the ordinary; there is a nightmarish quality to the photograph, compounded by the fact that the viewer is aware of its reality.

Maar's image is titled after the antihero of Alfred Jarry's play Ubu Roi (1896), a proto-Surrealist work that celebrated the absurd and the psychological. In this way, Maar suggested that the armadillo could be compared to human nature: bestial, compelling, and yet repulsive.

Silver gelatine print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Beginnings of Dada and Surrealist Photography

Dada and Photography in Germany

The Dada movement was established in Germany after World War I. It attempted to create a new kind of art that was valued primarily for its conceptual properties rather than focusing on aesthetics or literal documentation. Dada quickly spread to France and the US (to Paris and New York in particular), but many of its proponents who worked with photography remained in Germany. One of the key ways in which the Dadaists attacked traditional art was through photomontage. Artists such as Max Ernst and Hannah Höch used scissors and glue to cut up found (and occasionally original) photographs from a number of sources and reassemble them, using contrast and juxtaposition to emphasize their message. The use of photomontage as an art form was one of the most important ways in which the Dadaists shook up the traditional aesthetic order of the art world.

Photographic Beginnings in Paris: Eugène Atget

Meanwhile, in Paris, photographer Eugène Atget was using an old-fashioned camera to experiment with photography as an art form. Atget took photographs of Parisian streets, exploring how the camera both accurately captured the locus of everyday life, and also allowing him manipulate the same image so that it lost its grounding in reality.

Even though Atget had been experimenting with photos of shop windows for a decade, his work would come to prominence in the 1920s. His ethereal pictures became dual portraits, showcasing both the unsettling presence of mannequins framed within glass, as well as the reflections in the windows produced by activities taking place in the world outside. These interior/exterior melds created a distinctively surreal vibe, a dreamy form of unreality. These (among other images) were hailed by artists such as Man Ray and Berenice Abbott, and can be seen as some of the earliest touchstones for Surrealist photography. Art historian Ian Walker argues that Atget's work "seems to form a bridge between 19th-century topographical photography and 20th-century modernism" and, in particular, Surrealism.

Man Ray's Photograms: From Dada to Surrealism

Man Ray, who was already an established member of the Dada movement, arrived in Paris in 1921, where he soon began to collaborate with artists, including Marcel Duchamp, and to experiment with photography. He began to explore the potential in many photographic techniques, including the photogram - an image produced without a camera. For example, a photogram might be made by placing objects onto photosensitive paper before exposing the composition to the light, resulting in a negative image of the objects. Man Ray called these images "Rayographs," claiming their signature for himself. In 1922, he published a work called Champs Delicieux, where a text by the dada poet Tristan Tzara was accompanied by a series of his "Rayographs." Tzara described these early photographs in a way that emphasizes their instability and uncertainty: "Is it a spiral of water in the tragic gleam of a revolver, an egg, a glistening arc or the floodgate of reason, a keen ear attuned to a mineral hiss, or a turbine of algebraic formulas?" The publication was one of the early works to connect photography with the emerging Surrealist movement in early 1920s Paris.

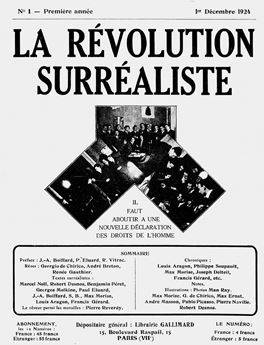

The Surrealist Manifesto

While Man Ray was experimenting with photography, Andre Breton was forging ahead with the establishment of a new avant-garde movement. Surrealism was officially launched with the Manifesto of Surrealism, authored by Breton in 1924. The main premise behind the movement was a rejection of reason and logic in exchange for an emphasis on free imagination and creativity, achieved through accessing or unblocking the unconscious. The movement caught on in both literary and artistic circles, with many practitioners working with both words and images to explore dreams, chance, or psychic automation, in an attempt to capture what Breton termed "convulsive beauty."

Many of these artistic reactions were a response to the horrors unleashed by the First World War and the breakdown in rational order and psychic wholeness that many people experienced as a result of it. The Surrealists discovered that normality was not necessarily a fixed concept, and that reality was entirely determined by perception. Psychological trauma, such as that experienced by many soldiers, could open new vistas of "reality" based on a mentally disturbed state. By processing these states through an art of the subconscious, the Surrealists were forerunners to the psychological concepts of mining the interior world.

Separating Photography from Surrealism

Although some key members of the Surrealist movement dabbled in photography, it was generally the fringe artists of the movement who enthusiastically embraced it as a sub-genre. As Christian Bouqueret argues in his monograph on Surrealist Photography, "with the exception of Jacques-Andre Boiffard [...] no photographers were directly involved. There were, of course, some who trod a long and parallel path, such as Man Ray [...] and others who joined the movement for a time, while maintaining a degree of detachment: Brassai, Dora Maar, Raoul Ubac, Claude Cahun, etc."

In some ways this is surprising, but it is also easy to see why photography was not an immediately obvious choice for many Surrealists. Before the 1920s, photography was primarily known as a scientific tool for capturing accurate images of the world, of documenting life, which suggested a conceptual opposition to the Surrealists' aim of capturing the imaginary, the fantastical, and the psychological. However, for a handful of progressive practitioners, photography was recognized as a tool that could be effectively subverted in the name of Surrealism in order to capture different kinds of reality. They did this through collage and juxtaposition, or through manipulating a familiar object in order to make it appear unknown, which invoked the idea of the uncanny, a key principle of Surrealist inquiry.

Journals

One of the most important ways in which photography became more closely associated with Surrealism was through the publication of journals. Breton's publication of The Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 was accompanied by the launch of a new journal, La Revolution Surrealiste. As art historian David Bate points out in his book Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social Dissent, it is only with the publication of this journal that photography began to play a bigger role in the movement and its dissemination: "The first issue of the journal La Revolution Surrealiste in December 1924 marked a shift, not only with the inclusion of 'revolution' in its title, but also its changed contents. It was also here in La Revolution Surrealiste that photography became a really significant means of representation in the Surrealist project." He points out that every subsequent issue of the journal had an increasing number of photographic images in it. This is partly because photographs could be reproduced easily and circulated through the means of journals such as this, allowing the visual aspect of the Surrealist movement to reach a much wider audience than would otherwise be possible. Due to this practical need for photography, there was also a growing response from artists both within and outside the movement to develop photography as a Surrealist art form.

Dada and Surrealist Photography: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Photomontage

Dada artists such as Max Ernst and Hannah Höch were principals in the evolution of photomontage. Such use of juxtapositions allowed Dada artists to eradicate the original meanings of the photographs and re-contextualize contemporary issues. The photomontage technique was also used by a number of Surrealist artists, including Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. For the Surrealists, the attraction of photomontage was principally that it could be used to make the familiar seem strange and echo the fragmentary nature of dreams.

Post-Production Manipulation

A number of Surrealist artists used techniques of post-production to manipulate their photographs. This might involve adding a graphic detail to a print before re-photographing it, such as in Man Ray's famous work Le Violon d'Ingres (1924), where he doctored the image in order to distort our understanding of the picture plane and of the photographic process. Alternatively, this might involve staging a photograph and then retouching it as in Philippe Halsman's and Salvador Dalí's Dalí Atomicus (1948), where a cat, some water, and Dalí himself fly through the air alongside floating tables. The fishing wire used to suspend the furniture was removed in post-production to finalize the image.

Commonplace Surrealism

A number of Surrealist photographs were taken of everyday places, people, and items, but were cropped or staged in such a way as to force the viewer to question their perception of reality. For example, Andre Kertesz photographed his Distortions series in a house of mirrors at a fun fair. The resulting images capture a moment of reality, but they appear to be grotesque and unreal. Similarly, Dora Maar photographed a number of ordinary items but cropped or presented them in an unexpected way. In her Father Ubu (1936), an armadillo fetus appears to be entirely alien.

Image and Text

There is a strong connection between Surrealist photography and language. Some works included text in the body of the piece, such as in René Magritte's Je ne vois pas la femme cachee dans la foret (1929). The meaning of some works became dependent on their title or caption. For example, Man Ray's Dust Breeding (1920) was a close-up image of dust collecting over the surface of Marcel Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923). The photograph was originally published with the caption "view from an aeroplane," pointing to the way in which our understanding of a photographic image is dependent on its linguistic context.

Later Developments - After Dada and Surrealist Photography

Although the Surrealist movement faded away by the mid-1930s, Surrealist photography has had a surprising longevity. Artists such as Claude Cahun continued to produce work in a similar, if not identical, vein well into the 1940s. Man Ray similarly continued to work in photography, often capturing significant members of the art world in unusual portraits. Some street scene photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Helen Levitt would borrow Surrealist notions of discovering the uncanny in their everyday decisive moments. Surrealism can also be found in the early works of many of the mid-century's photography greats including Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Diane Arbus.

Many of these artists had a significant impact on later generations. The ability of the camera to both conceal and reveal, and to create a different kind of reality - first pushed to its limits by the Surrealist photographers - is something that continues to inspire artists today. In particular, artists who worked with issues of gender and sexuality continued to have an impact. Claude Cahun, for example, is cited as a key influence of a number of female artists working with photography, self-portraiture and disguise, such as Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing.

Furthermore, a number of contemporary artists cite the Surrealist photographers as an influence due to their interest in photographing things that are not as they first appear. For example, Man Ray and Duchamp's aforementioned Dust Breeding (1920) directly inspired Sophie Ristelhueber's À cause de l'élevage de poussière, her 1991 aerial photograph of the Kuwait desert just after the expulsion of Iraqi forces.

Useful Resources on Dada and Surrealist Photography

- Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social DissentOur PickBy David Bate

- Surreal Photography: Creating The ImpossibleOur PickBy Daniella Bowker

- Ghosts of the Black Chamber: Experimental, Dada and Surrealist Photography (1918-1948)By Candice Black

- Surrealist PhotographyBy Christian Bouqueret

- Forbidden Games: Surrealist and Modernist PhotographyBy Tom Hinson, Ian Walker and Lisa Kurzner

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI