Summary of American Realism

The birth of Realism in art is often given a specific time and place - France, 1840 - from whence it spread (and transformed) as a pan-European response to the age of industrialization. It remains, however, an open-ended concept that has taken on a uniquely national bent when applied to American art. What might be generally agreed is that Realism is a tendency whereby the artist in question has either subverted, or overlooked altogether, Academy (or typical orthodox) standards in pursuit of a more "authentic", or "relevant", figurative art. Realist art typically responds to contemporary events and situations, sometimes as a form of social commentary or documentation. Not so much a movement, then, American Realism is a tendency that has traveled the timeline of American history since its birth as an independent country. Indeed, through its various manifestations, Realism has become an important instrument in shaping America's self-identity as a nation.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- By most art historians' accounts, John Singleton Copley holds the rank the greatest American painter of the eighteenth century. Known primarily for his portraits, he developed a realist style that captured his sitters, some of them the most important pioneers of the New World, in a naturalistic way and with very fine attention to small detail. Priding himself on his political neutrality, Copley brought a level of objectivity to portraiture that was wanting in even the best examples of his more austere European contemporaries.

- In was an English émigré named Thomas Cole who instigated the rise of America's first school of landscapists. On the one hand, the Hudson River School was captivated by the majesty of the American landscape and its members bought into the European idea of the sublime power of nature. At the same time, the group, who took great national pride in the majesty of their own natural surroundings, began to record the dawning of the industrial age and America's ability to harness this "untamable" force. Overall what they achieved was a fine balance between the realms of realism and illusionism.

- The loose-knit group of New Yorkers, known as The Ashcan School, delivered American art into the twentieth century by countering the soft palettes and flights of colorful splendor associated with the American Impressionists. The Ashcan School believed that an authentic American art could only be achieved through direct experience and by capturing the dynamics of city life on their canvases. Though they were apt to intensify the drama of their pictures through their preference for dark palettes and loose brushstrokes, theirs was a gritty and vital take on the realities of New York street-life at the beginning of the century.

- The combined impact of Great Depression and the Dust Bowl crisis of the 1930s led to the development of national relief programs that included roles for artists and photographers in the worst-affected communities. In the Mid-Western Heartlands a style known as Regionalism emerged. Reviving the traditions of folk art, the Regionalists promoted archetypal American rural subjects that embodied the values of hard work, community, and austerity. The social project was mirrored in cities like New York where the Social Realists were producing figurative and realistic public murals of and for "the workers". The Social Realists insisted that their art be uses as a political "weapon" to be deployed against the perceived ills of American capitalism.

- Following the intervention of Abstract Expressionism, American art renewed its interest in realism in the 1960s. The Photorealists, or Hyperrealists as they were also known, produced paintings that drew heavily on photography. With the photographic image projected onto the canvas, the Photorealists then produced precisely detailed paintings that they then made "hyperreal" by "touching up" with the veneer of an airbrush. Focusing mostly on machinery and objects of industry (cars, trucks, planes, vending machines and so on) and (specifically in the work of Audrey Flack) current news photography, the Photorealists offered a counter to the rise of Conceptualism and Minimalism.

Overview of American Realism

George Bellows, one of the most prominent members of the New York Ashcan School, declared: "First of all, I am a painter, and a painter gets hold of life - gets hold of something real, of many real things", and when he does that, "that makes him think, and if he thinks out loud he is called a revolutionist".

Artworks and Artists of American Realism

Paul Revere

Singleton Copley was, by common consent, the greatest American painter of the eighteenth century. His painting of Paul Revere, the silversmith-cum-folk-hero of the American Revolution, predates Revere's historic night-time ride to Lexington on the eve of the revolution that alerted the colonial milia of the approach of British troops (and thus allowing Revolutionary leaders John Handcock and Samuel Adams to escape capture) and reveals him very much as an "ordinary" artisan.

On the one hand, Copley's painting presents an idealized version of Revere's working conditions: the table is too uncluttered and polished to resemble a working bench and the silversmith's clothes and hands are washed clean. On the other, it is, by the standards of the day, a naturalistic portrait. At a time when it was the norm for sitters to present to the artist/public in their "Sunday best", Revere is shown in his working clothes, a feature that hides his middle-class status. For instance, his shirt is fashioned from plain white cotton, he is missing and formal neckwear (such as a cravat) and his waistcoat is unbuttoned. Nor does Revere wear a jacket or wig, the latter especially being a staple status symbol for a person of Revere's social standing.

Although Copley prided himself on his political neutrality, his portrait of Revere carried with it more than a hint of political symbolism. A silversmith would craft many objects - buckles, cutlery, tankards, sugar tongs and so on - yet the fact that he is pictured with a teapot seems like a political statement. The year before the painting was produced, the British government has passed to so-called Townsend Act which imposed taxes on tea (in addition to some other imported goods). Tea had become a divisive commodity and led, ultimately, to the Boston Tea Party of 1773 in which radicals raided vessels in Boston Harbor and threw the cargo of tea overboard.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm - The Oxbow

Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School, supported the 19th century notion that God's divine presence was embodied in nature. And, perhaps because he was an Englishman, Cole was better placed (as an outsider) to appreciate the American wilderness as central to American national identity.

On the left diagonal, we see the evidence of the sublime (an artistic trope that expresses the "sublime" power of God through nature) as a thunderstorm of biblical proportions pours down angrily on a lightening-struck tree. While the left half of the composition is taken up by thick verdant woodland, deep greens and looming darkness, as our eye crosses the river, the image shifts in emphasis. Now we see a more pastoral scene rendered in lighter colors that speak of man's mastery over the fearsome landscape. This gives the painting its unique contemporaneous theme of manifest destiny.

Art historian Edward Lucie-Smith described this work as "an effort to marry a sensibility based on Claude Lorrain and the European ideal landscape to the recalcitrant facts of American nature". This is shown most emphatically to the right of the canvas where the grasses have been tamed by modern advances in agriculture. It was important for art of the time to represent farms and homesteads as a way of demonstrating how the pioneers had begun to own this majestic land of theirs. Furthermore, Cole wanted to show how the beauty of America's countryside could compete with the best that Europe had to offer. He wrote in 1835: "There are those [Europeans] who through ignorance or prejudice strive to maintain that American scenery possesses little that is interesting or truly beautiful [...] Let such persons shut themselves up in their narrow shell of prejudice - I hope they are few - and the community increasing in intelligence will know better how to appreciate the treasures of their own country".

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Gross Clinic

Thomas Eakins was one of the founders and teachers of Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts. Born and raised in Philadelphia, which at the time was the cultural capital of America, he showed an early talent for drawing. Working primarily in the second half of the 19th century, Eakins' style renounced idealized and romantic depictions and advocated instead for precise investigation of the human form and the natural world. He was fascinated with photography and made photographic studies of humans and animals in motion and thus pioneering a painterly style based on direct observation. The Gross Clinic celebrated the work of local physician Dr Samuel David Gross, who was instructing doctors on new surgical techniques as they removed a dead piece of bone from a young man's leg.

Inspired by Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp (1632), Eakins' bloody composition is one of two parts. The top renders spectators in the theatre in soft, impressionistic detail. Hidden in the dark, some are busy working, others are clearly bored. In the foreground, however, Eakins's use of light picks out the important details such as the look of instruction on Dr Gross's face, the white cloths soaked in liquid anesthesia (ether), the blood on his and his colleagues' fingers, and the surgical tools (many of which Gross invented himself). The juxtaposition of dark and light; pain and boredom; bloody flesh and metal, represent the tension at the heart of American Realist painting: the new world is catching up with the old and a nation of wilderness is becoming an industrial superpower. However, many critics protested at the visceral nature of the work which upset Eakins's standing in Philadelphia society. Nevertheless, the work stands as a record (and celebration) of the great leaps and innovations in science and medicine coming out of America in the late nineteenth century.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art & the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Stag at Sharkey's

Associated primarily with the rise of New York's Ashcan School, Bellows is perhaps best known for his sports-themed works, and especially, a series of brutal boxing paintings. His signature work, Stag at Sharkey, involved an illegal bout which he was drawn to, not for the sport (which he claimed not to understand), but for its raw brutality. Amateur boxing bouts were illegal in New York and so contests such as this had to take place in privately run clubs. Tom "Sailor" Sharkey, a US Navy veteran, and former boxer himself, founded his eponymous club as a venue for men seeking to watch and/or participate in amateur boxing bouts. When an outsider came to compete, they were given temporary membership to the club and were known as "stags". Bellows, whose studio was located across the street from the venue, was able to watch fights and produced several preparatory sketches.

Two boxers are locked in a hold as they compete in the center of a ring. The rivals are represented through a pyramidal composition. Looking for potential rule infringements, meanwhile, a referee is hunched closely to the right of the fighters. A cigar-chewing ringside spectator turns towards the painter, imploring him (and the viewer), through his pointing finger, to give our full attention to the fight at hand. Indeed, Bellows separates the fighters from their surroundings, not only through the ringside ropes, but through the bold, but naturalistic, use of color and shading. The realist quality of the painting is evident not just in the choice of subject matter and setting, but also in Bellows's skill at rendering the intense physicality - the interlocked, sinewy bodies of the boxers - and energy - the rumbustious crowd and the urgent (futile?) intervention of the referee - by means of fluent impressionistic brushstrokes. Many have read this painting, one of the most iconic of twentieth century American art and as the perfect analogy for the trials and tribulations of working-class urban survival in the early years of the century.

Oil on canvas - The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

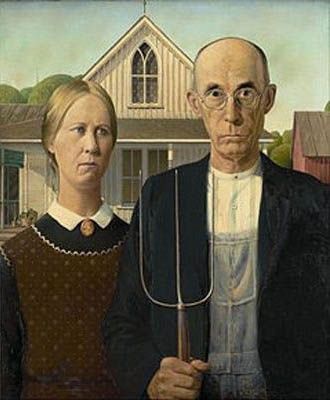

American Gothic

Grant Wood, one of America's foremost Regionalist painters, made a name for himself painting archetypal rural subjects that embodied the values of hard work, community, and austerity. He shot to fame almost overnight and captured the public's imagination with this and other works that celebrated a version of American identity through clarity and precision. Wood produced this work while visiting the small town of Eldon in his native Iowa. Inspired by the little wood farmhouse, with a single oversized window made in a style called Carpenter Gothic, Wood said he "imagined American Gothic people with their faces stretched out long to go with this American Gothic house". His models were his dentist and his younger sister, Nan (though many read them as man and wife). Both are dressed in conservative dress and painted in dark, stern colors. The pitchfork in the centre - which was an old-fashioned tool even in the 1930s - dominates the frame. While the subject matter was distinctly midwestern, the highly detailed, polished style and the rigid frontality of the two figures came from the realist Flemish Renaissance art which Wood had studied during his travels to Europe a decade before.

Despite being an overtly realist work, Wood's painting has in fact been met with confusion and ambiguity. Some commentators are still unsure as to whether this painting celebrates the subjects or satirizes them. Does it represent the present moment? Or is it nostalgic? Art historian Edward Lucie-Smith said: "The Regionalist movement, was thought of celebratory by its participants, a revival of the values of the Midwestern heartland of America - this in spite of the fact that the Midwesterners of the time were often resistant to, and sometimes deeply offended by, the way in which leading Regionalists chose to depict them". Wood himself did not offer much by way of clarity when his painting was displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago (winning him a $300 prize). He said simply that it represented the "types" he had known all his life, and that he had not intended to ridicule them by pointing to faults such as "fanaticism and false taste". However one chooses to read it, the painting has become iconic and is one of America's best known and well-loved works.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

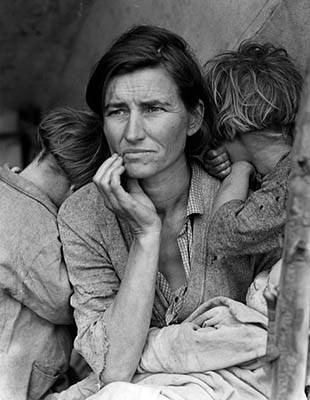

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

An image as iconic as Wood's American Gothic, Migrant Mother is one of the most widely recognized photographs in documentary history and shows a woman in a migrant pea-pickers camp during the Dust Bowl crisis. Their faces turned away from the camera, her two young children cling to their mother as she holds an infant, swaddled in a worn blanket, and looks pensively into the far distance. The photograph was originally captioned "Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California" and was one of several images that Lange took of Florence Owens Thompson and her family in their makeshift camp.

The image was in fact part of a documentary project, supported by the Resettlement Administration, and subsequently renamed the Farm Security Administration, where Roy Stryker, head of the photographic division, hired photographers, "to document the American way of life". Lange's photographs appeared in a 1936 issue of the San Francisco News, following a story highlighting the near starvation conditions in the camp, and contributed to the success of the relief effort. Stryker felt Lange's image symbolized the entire project. As he said, Migrant Mother "has all the suffering of mankind in her but all of the perseverance too. A restraint and a strange courage. You can see anything you want to in her. She is immortal". Reproduced in textbooks, postage stamps, political campaigns, and museum displays, the image has become not only a symbol of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl crisis, but also, as historian Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites put it, "a template for images of want" and a "powerful statements on behalf of democracy's promise of social and economic justice".

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

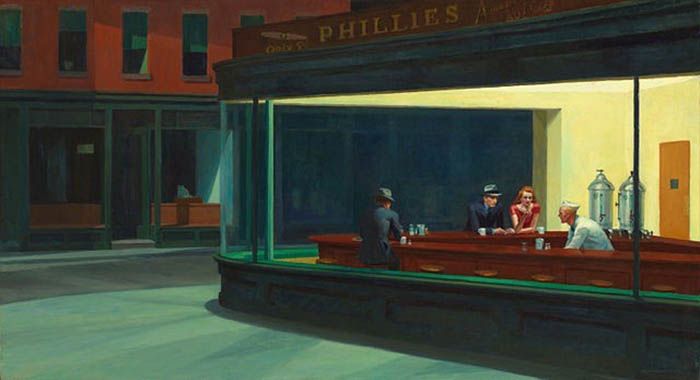

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper, a careful, thoughtful, artist who would observe his scenes for hours before putting brush to canvas, created more than 800 paintings, watercolors and prints, as well as numerous drawings and illustrations. He depicted the realities of modern alienation through images of people whose faces were often so still they seem arrested by time. As art historian Avis Berman wrote: "Each canvas represented a long, morose gestation spent in solitary thought". Nighthawks has become one of the best known images of twentieth-century art. Inspired by a restaurant on New York's Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet, the image - with its carefully constructed composition and total lack of narrative - has a timeless, universal quality that transcends its particular locale. The large windows of the diner show four individuals, sitting together but alone at a countertop under fluorescent lighting. They are seemingly sat in silence, lost in thought at an unspecified time of night. If there is conversation, the viewer is not invited. Of Nighthawks Hopper said: "unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city".

This piece embodies the Americana that much of the Realist art of the time displayed; the coffee, the cigar advert, the cash register, the salt and pepper shaker and napkin holders all invite the viewer to share in their lived experience of the anonymous diners. It was signifiers such as these that prompted some critics to associate Hopper with the Ashcan School (although at that suggestion the artist himself baulked, "I've never painted an ash can in my life" he said). As art historian Dr Beth Harris said: "There is an implication that we are alone. It almost starts to feel frightening. But you can imagine light around it at another time of the day. It's now eerily silent. We just want to know - what are these figures doing here". This echoed the heightened feeling of alienation during wartime America. The cities emptied under the cloud of anxiety hanging over the nation.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

This is Harlem

African American artist Jacob Lawrence, an alumnus of various New York Art schools, was a member of the New Deal, Federation Art Project. He was also a part of the Harlem Renaissance - a New York movement that was committed collectively to representing the lived experience and history of African Americans but without a single unifying style - Lawrence combined elements of Social Realism and semi-abstraction in compositions that used a vivid palette to create compelling community narratives. Lawrence wanted to bring the Black experience into the canon, after realizing from a young age that his education neglected African American art history. Lawrence painted from his everyday life and in This Is Harlem we see a colorful street scene represented through advertising hoardings, telephone cables, a community church, and crowded residential blocks. Through the middle of the canvas march city-dwellers, hands pushed into pockets as they hunch from the cold. The picture plane is flattened and the perspective is off kilter - a human dwarfs a passing truck while a dog out-spans a car, for example.

In comparison to other Realists working in the city, Lawrence brought a greater sense of celebration and spirituality to his work. Harlem was a locus for music, literature, theatre and visual arts and this work pays tribute to the creative lifeblood of the neighborhood; from the figures cavorting on a street corner, the signage ("Dance", "Bar", "Beauty Shoppe"), the color of the church's stained glass windows and the posters/paintings hung on the sidewalk. Lawrence's style and subject matter reflected his desire to connect with a broad audience; the bold colors and detailed figuration were designed to promote the Harlem narrative. As curator Jacquelyn Serwer said, Lawrence wanted to make sure "that important aspects of African American history were documented in a way that could be appreciated and understood by a very broad audience".

Oil on canvas - Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington

Kennedy Motorcade

As Flack moved from her early career gestural abstraction and self-portraiture into Photorealism, she turned her gaze away from the self onto the realities of the outside world. She achieved the photo-real effect by projecting, tracing and re-colouring real historical events onto over-size canvases. She would often use an airbrush as a means of bringing the burnished gleam of advertising to her subject matter thus lending her art a hyperrealistic quality. Flack was one of several artists who moved beyond the introspection of abstraction towards the re-staging of popular imagery and culture. However, in the 1960s, and even in the wake of Pop Art, it was still considered problematic for serious artists to directly copy photographs.

John and Jackie Kennedy are seen here leaving Dallas airport on November 22, 1963, just moments before his assassination. Flack wrote: "People were horrified at the subject matter. Everybody is smiling, and, of course, you know that one moment later Kennedy is going to get shot". The couple sit in the back of a convertible car surrounded by security and airport staff, waiting to make their ill-fated parade through downtown Dallas. Flack reproduced this scene from a color newspaper photograph of the Kennedys published at the time. Caught squinting in the glare of the Texan sun, the Kennedy's, accompanied by state governor John Connally, appear relaxed and happy, unaware of the momentous historical tragedy which is about to unfold. Whatever one's view on the meaning of "authentic" art, Flack's Kennedy Motorcade ranks as an innovative example of a Photorealist style that invites the spectator to reflect on the ontology of original art.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Queenie II

As one of the most popular American sculptors of the twentieth century, Hanson first achieved acclaim during the 1970s through a hyperrealistic style that saw his sculptures likened to the painters of the Photorealism movement. He is associated specifically with a series of uncanny life-size models of working-class American citizens which he recreated in painted polyvinyl, fiberglass resin, and bronze. Hanson's sculptures are celebrated for their meticulous attention to detail which include such features as real hair, fingernails, raised veins, and various skin blemishes. Dressing his figures in workers uniforms, or clothes bought from thrift stores, he helped to further define the status of his subjects through the appropriation of various found props.

Hanson's hyperrealist works often trick the eye and the artist has spoken of his fascination with tromp l'oeil painters such as John Frederick Peto. But this knowledge rather belies the fact that his sculptures also offer a more reflective experience through their realist qualities. As he said, "In the turmoil of everyday life, we too seldom become aware of one another. In the quiet moments in which you observe my work, maybe you will recognise the universality of all people". Hanson was not trying to trick his audience into thinking his figures were somehow real, however. His intention was rather to illicit a sense of connectivity between these everyday American "types" and the people who came to the gallery to view them. Some critics still read his pieces as satire because there was a humorous quality to be had by (dis)placing his figures in surroundings (the gallery) that were unfamiliar to them. But humor notwithstanding, Hanson's intentions always remained true to his empathetic humanist worldview.

Polychromed bronze, with accessories - Van de Weghe Fine Art, New York

Michelle Obama

Sherald's art focuses on African American cultural history and specifically the representation of the African American body in black and white photography. Her work is, in the words of art critic William S. Smith, part of a move in contemporary American Realist art to "narrate histories of struggle, ennoble quotidian experiences, and project a better future without lapsing into idealism". Sherald adopts a monochrome technique, known as grisaille (shaded grays), to render the former First Lady's skin tone. On the one hand, this strategy was a means of challenging the viewer's assumptions about color as race, but the grisaille technique was also a direct reference to Sherald's childhood when she learned of her grandmother through studying old black and white photographs in which her skin was represented in like tones of monochrome. Indeed, Sherald described her paintings as a "meditation on photography".

The Smithsonian says of the painting: "Mrs. Obama's unnaturally colored skin asks us to consider both her race and her humanity. While the use of gray in lieu of more natural skin tones reduces the reference to her race, the blunt removal also draws attention to her skin color, highlighting her racial identity. The gray tones, in particular, reference nineteenth-century photographic traditions, wherein the emerging photographic medium allowed free African Americans to celebrate themselves and craft their own unique (and positive) identities. Whereas the grand portraiture traditions of painting and sculpture were largely out of reach, photography was an accessible medium". The other dominant feature of the portrait is Mrs. Obama's personal choice of dress. Designed by Michelle Smith, and looking beyond its nod towards 1960s Op Art, "Sherald recognized its visual affinities with the quilts of Gee's Bend, Alabama. The quilts of Gee's Bend, a remote black community of the descendants of former slaves, are bold and improvisational, and reference the independence and resourcefulness of the African American experience".

Oil on linen - National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Beginnings and Development

Now ranked as the first internationally recognized American painter, Benjamin West is chiefly associated with academic style of Neoclassicism (and, in his later career, Romanticism). Indeed, his most famous historical narratives, such as his career defining Death of General Wolfe (1770), were designed specifically to elicit an emotional response in the viewer by inviting them to sympathize with noble human acts (such as General Wolfe's self-sacrifice at the Battle of Quebec). But his Neoclassical compositions were somewhat atypical, not just because he focused on contemporary subjects and events, but also because West introduced finely observed contemporary details into his tableaus such as clothing and weaponry. For his part, Copley adopted a direct approach to his sitters. It was a style that presented a fierce challenge to the more austere Academy portraiture and gave rise to a series of naturalistic portraits that have become the definitive visual record of the dignity and valour of New World pioneers including John Hancock (1765), Paul Revere (1768), and Samuel Adams (1772).

![George Caleb Bingham, <i>Fur Traders Descending the Missouri</i> (1845). The Met Museum describes how this work was titled by the artist “French Trader & Half breed Son” but New York's American Art-Union (which promoted American art nationally) changed it to its less controversial title, adding that the “tranquil scene, with its luminous atmosphere, idealized the American frontier for the benefit of an Eastern [American] audience”.](/images20/photo/photo_american_realism_2.jpg)

Blending idealism with realism, The Hudson River School (1826-70), whose members - including Asher B. Durand, George Inness, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt and John Frederick Kensett - were drawn to (what was at that time) the unique upper New York state wilderness, is considered the first unified American art movement. Taking their lead from the spectacular landscape paintings of the English émigré Thomas Cole, the "second generation" Hudson School (from 1848) imported the influence of European Romanticism, the idea of the sublime, and adopted the allegory that the magnificent American landscape, especially so when brought to life on vast canvases, symbolized the limitless possibilities for a fledgling American nation. This style was however tempered by a pronounced realist element that emerged in the Group's collective commitment to Naturalism which was most evident in the artists' meticulous attention to the details in nature.

Bingham, meanwhile, was the foremost midwestern landscapists of the first half of the 19th century. His depictions of Missouri frontier life (during the 1830s and 1840s, Missouri remained at the edge of the American frontier and a point of departure for explorers and pioneers heading west), in images such as Fur Traders Descending the Missouri (1845), created a representative, if unabashedly idealized, picture of the day-to-day working life in and around America's midwestern waterways.

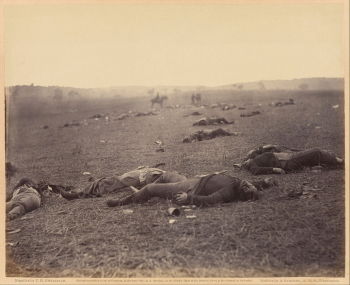

Homer and Eakins

Winslow Homer is regarded by many as the greatest nineteenth century American painter. He is best known perhaps for a series of raw gestural works that depicted man's struggle against the mighty forces of the sea. Prior to this, however, he had developed a style of Realism that set precedents for American art. In October 1861 he was dispatched to Virginia as a war artist/correspondent for the journal Harper's Weekly. His civil war paintings, such as The Army at Potomac - A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty (1862) and The Veteran in a New Field (1863) reflected his first-hand experience of the war and its human impact. Indeed, Homer's war paintings were executed with a detached objectivity that avoided the romanticized and heroic battle scenes that were a staple of history paintings.

Homer's works mirrored in fact the "new" war documentary photography being produced simultaneously by Matthew Brady and his team (including Timothy O'Sullivan, Alexander Gardner, and George N. Barnard). Collectively Homer and Brady's team provided a definitive documentary record of the American Civil War. Once the war had ended, Homer turned his attention to everyday rural scenes of women and school-children at work and at play, and to hunting scenes. In the mid-1870s, Homer returned to Virginia where he turned his observational eye (and brush) this time towards the daily lives of former slaves during the first decade of Emancipation. Meanwhile, Homer's contemporary, the domestic portraitist and painter of sporting scenes (such as swimming and wrestling), Thomas Eakins, produced paintings with an almost scientific detachment. Eakins was one of the first American artists to embrace the medium of photography and he used it as a tool on which construct his compositions. He sought to create an anatomically accurate human forms and would be a key influence on the Ashcan School that carried the torch of American Realism into the twentieth century.

The Post-War West

Jonathan Eastman Johnson (aka Jonathan Eastman) was the eminent American genre painter on the late nineteenth century (a fact acknowledged as he was the co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) who made his name both as a portraitist (his sitters included Abraham Lincoln, Nathanial Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) and a painter of everyday American life. He had studied at Germany's Düsseldorf Academy and in The Hague during the 1850s and his work owed an obvious debt to the seventeenth century Dutch masters (hence his moniker: "the American Rembrandt"). Johnson's painting presented a clear departure for American Realism in that it helped widen the definition of what it meant to be an "ordinary American".

His everyday vignettes were not idealized or romanticized while his paintings of life in the West dealt head on with the sensitive issues of slavery and poverty. Indeed, in 1859 his New York exhibition, Negro Life in the South, caused disquiet amongst audience members. His images of the leisure activities of a group of slaves proved a sensation at a time when the injustices of slavery were at the top of the political agenda. Such was the success of the exhibition Johnson was made Associate to the National Academy of Design. In subsequent decades Johnson turned to themes of national life, painting humble interior scenes near his second home on the island of Nantucket. (In his later career he gave up genre painting and returned to portraiture for which he received handsome fees.)

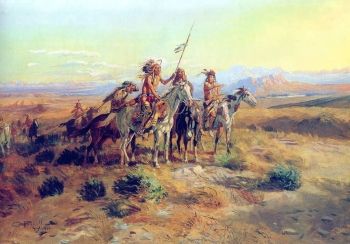

Post War Frontier life

Born in 1864, Charles Marion Russell (aka Kid Russell), would produce dynamic Cowboy Art based on his intimate knowledge and experience of frontier life in and around Montana. Raised in a comfortable middle-class home in St. Louis, Missouri, Russell was an avid reader of dime-store westerns and spent his childhood daydreaming of life as a cowboy. Concerned with his poor school record, and his frequent bouts of truancy, Charlie's parents sent their 15-year-old son on a summer vacation to a ranch in Montana in the hope he would learn some discipline. He never came home. Coinciding with the western cattle boom, Russell had realized his dream by taking on a two-year apprenticeship as a horse wrangler. As a way of passing his down time, Kid Russell would sketch scenes of cattle drives and model horses from wax.

Russell made friends of the Blackfeet, Arapaho, Kootenai and Crow tribes before, in 1888, living with the Kainai Nation (aka The Bloods), with whom he hunted, learned their language, legends and customs and incorporated their tribal symbols and emblems in his painting. As the art historian Arthur Hoeber put it, Russell "paints the West that has passed from an intimate personal knowledge of it; for he was in the midst of it all, and he has the tang of its spirit in his blood".

The Ashcan School (1900-1915)

The term "ash can art" was first used around 1916 and is attributed to the artist Art Young. The label, Ashcan School, and its later incarnation, The Eight, has been applied to a number of Philadelphia and New York painters (and even photographers such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine) working in the first two decades on the twentieth century. While there is a lack of agreement on who "belonged" legitimately to this rather informal group, Robert Henri, George Bellows, John Sloan, William J. Glackens, George Luks and Everett Shinn, and later, Edwin Lawson, Maurice Prendergast and Arthur B. Davis are considered amongst its principle players. Though they were committed to representing the realities of everyday urban life, the artist's believed in freedom of expression and the idea that artists should be free to exhibit their works without pressure from academies and awards juries.

Prior to the emergence of the Ashcan School, the plein air style was the dominant trend in American painting. With their light palettes and loose brushwork, the likes of William Merritt Chase and Mary Cassatt carried the torch for the romantic idyls that became known as American Impressionism. Inspired chiefly by Henri - who worked off the maxim "art for life's sake" - the Ashcan artists set themselves apart from the Impressionists. The Group concerned itself with subject matter centered on the dynamism of metropolitan street-life. Featuring scenes of sports bars, alleyways, movie theaters, boxing arenas, and the daily lives of prostitutes, immigrants and working-class communities, the School's loose style borrowed variously from the traditions of seventeenth century Spanish and Dutch, and nineteenth century French, realism. But it was perhaps George Bellows, taught by Henri and influenced by Eakins, who emerged as the true progenitor of American Urban Realism. His oeuvre reveals the artist's readiness to tackle a range of urban subjects and to experiment with new color and compositional arrangements.

Precisionism and Regionalism

The American avant-garde took off proper following the International Exhibition of Modern Art (known as the Armory Show since it was staged in vast US National Guard armories) of 1913. It was a landmark event in the history of American modernism, giving rise to what was considered the first truly homegrown avant-garde movement: Precisionism. Although Precisionists such as Paul Strand, Charles Scheeler, Georgia O'Keeffe, Niles Spencer and Ralston Crawford took their lead from the distilled geometric forms of Cubism, Futurism and Orphism, their subject matter, which included city streets, skyscrapers, rail networks, steel works and grain depots, saw them tackle much of the same subject matter as the Ashcan School (indeed, Edward Hopper has been claimed variously by historians for both groups).

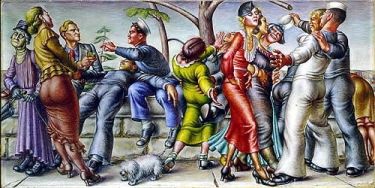

However, once the Great Depression and the Dustbowl crisis had taken hold, many American artists challenged the "self-indulgences" of semi-abstraction by producing a narrative art that spoke directly to the folk living in the American Heartlands. The best-known of the Regionalists were Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood. They produced art that reflected the hardships of provincial American life (although the sincerity of their work has since been the cause of some debate amongst art historians). Collectively, the Regionalists were associated with an authentic local art that overlapped the traditions of American folk with even Old Master paintings. Curry found favor producing idealized and nostalgic, depictions of community and religious life while Wood produced American Gothic (1930) one of the most iconic American artworks in the country's history.

Among the best-known Regionalists was Doris (Emrick) Lee. Indeed, she emerged as one of the most successful female artists of the Depression era. Lee's tableau of women preparing a Thanksgiving banquet drew national headlines when it won the prestigious Logan Purchase Prize in 1935. The theme of Thanksgiving tied in with the Regionalist focus on rural life customs which Lee executed in style reminiscent of American folk art. Works such as this were hugely popular with those still living in the grip of the Great Depression but Josephine Logan (donor of the Logan prize) condemned Lee's "exaggerated" style. Indeed, the following year Logan founded the conservative "Society for Sanity in Art" in protest. The Society opposed all forms of modernism and any mode of art that deviated from academy standards. Branches of the Society established themselves all around the country and artists associated with the group included: Haig Patigian, William Winthrop Ward, Florence Louise Bryant, Henry (Percy) Gray and Frank Montague Moore.

American Social Realism

Overlapping with Regionalism, was the urban American Social Realist movement. It was in fact a global movement that was particularly prevalent in Communist and/or Socialist countries (such as the Russia, China, and Mexico) where state sponsored art was used to the ends of state propaganda. Socialist Realism was/is a figurative and realistic art in which the lives of "the workers" and the politically disenfranchised are celebrated in an act of social solidarity. The Social Realists rejected avant-gardism as being elitist and therefore lacking inof social resonance. For these artists, art should serve as a political weapon in the fight against capitalist systems and, in other instances, to attack the advance of international fascism.

The American Social Realists objected to the sentimentality and national stereotypes they saw in Regionalism and, in New York (the bedrock of American leftist politics), the Fourteenth Street Group formed, by Kenneth Hayes Miller, championed the working men and women of the city. The sense of group activity was echoed in the collective actions of the artists who joined pickets, protested vocally against social injustices, and made demands for permanent recognition by the government. Comprising, amongst others, the Russian -born Soyer brothers (Isaac, Raphael, and Moses), Isabel Bishop, and Reginald Marsh, the group found poetry in the messiness of quotidian city living. William Gropper and Ben Shahn, meanwhile, took Social Realism to a more overtly political level with works that incorporated a note of caricature. Jacob Lawrence, meanwhile, formed part of the Harlem Renaissance movement. As part of a cultural movement that did not prescribe a realist style (or any one style for that matter), Lawrence combined elements of Social Realism with abstraction in narrative works that reflected the Harlem neighborhood's collective commitment to creating visual stories of the lived African American experience and its history. By the 1940s, the rise of totalitarian governments, especially in Russia, saw Social Realism in America condemned as politically problematic. In New York especially, it would yield to the rise of Abstract Expressionism and all it came to symbolize about life in the "land of the free".

Concepts and Styles

Realism has a long legacy in painting and it is within this domain that it is (rightly) most regularly discussed. But as a concept, American Realism has extended its influence beyond the canvas and, despite the ascendency of abstract and conceptual art, it has continued to attract visual artists who are, or have become disillusioned, with the "difficulty" of avant-gardism.

Sculpture

Some of the earliest representations of American identity in sculpture can be attributed to Frederic Remington and his bronze Cowboy sculptures. His famous Broncho Buster (1895), for instance, was admired for its "frozen moment-in-time" rendering of a cowboy astride a bucking horse and he became well known for his small-scale works depicting the lives of frontiersmen and Native Americans. Following the Great Depression, meanwhile, some 17,000 sculptures were produced under the New Deal Works Progress Administration. Roosevelt's New Deal Recovery saw investment in public art that both provided employment for craftsmen, and cultural identity for towns and cities across the nation.

George Segal became well-known in the early 1960s for his life-size sculptures made of orthopaedic bandages soaked in white plaster (although in his later career he was known to dabble with color). His figures were cast form friends, family members and neighbors and were often displayed in public places like street corners, public benches and tables and train stations. Associated initially with the rise of Pop Art, his sculptures overlapped the line between popular culture and fine art with his own working-class New York upbringing influencing his interest in people intersecting in public social spaces. However, his sculptures - a style he referred to as "literal Cubism" - saw him discussed as more readily as a realist. Indeed, his ghost-like characters celebrated the mundane nature of everyday urban living and often carried with them the themes of boredom and isolation. Performance artist and art theorist Allan Kaprow said of Segal's figures that "They are almost real because they have substance and a name".

Murals

With funds supplied by the Federal Art Project, the Regionalists and other artists complimented their canvas paintings with a series of murals. In total, it is estimated that these artists produced some 2,500 murals between them. The mural represented the democratization of art, freeing it from exclusive galleries, and putting art on the street ("where it belonged") for everybody to enjoy. With a background in set design giving him experience of creating art on a large scale, Thomas Hart Benton was perhaps the best-known muralist of the Regionalists. His America Today murals for the New School for Social Research in Greenwich Village depicted life in different regions of the United States: the South, the Midwest, the West and New York. Even after Realism had given way to Abstract Expressionism, he went on to produce murals on the theme of the American Heartland in Chicago, Indiana, and Missouri.

Benton was the most cosmopolitan of his peers. Having studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, he moved to France where, before his permanent return to America in 1911, he mixed with the Parisian avant-garde and this influence showed in his fluid, sculpted figures. But it was the scale and grandeur of his murals that most ignited the public imagination. The mural for the Harry S. Truman Library, for instance, was delivered in his characteristic "semi-expressionist quasi-folksy realism" (as one critic described it). Benton rued: "If I make a tiny error in an Indian's headdress [...] or a rifle, people come down on me like a ton of bricks. They never criticize the artistic quality one way or another, but the historical detail must be absolutely accurate".

Photography

The advent of photography in the mid-nineteenth century had a profound influence on art and is cited by many historians as the device that effectively liberated the artist from the "obligation" of representing the world realistically (and hence giving birth proper to modernism). In America, the first and most well-known documentary project began in 1861 when Matthew Brady, hitherto a renowned New York photographic portraitist, brought together a team, including Timothy O'Sullivan, Alexander Gardner, and George N. Barnard, to document the American Civil War. Subsequently, Sullivan, with other photographers including William Henry Jackson, began working in 1868 for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, creating the first comprehensive conservation documentary of the American West.

Moving into the twentieth century, the combined impact of Great Depression and the Dust Bowl in the 1930s led to the development of new relief programs, including providing artists and photographers with jobs in the worst affected communities. Roy Stryker, head of the Resettlement Administration (later, the Farm Security Administration) hired leading photographers including Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and Walker Evans to introduce, as he said, "America in Americans". The project resulted in over a quarter-million images that were celebrated both as compelling portrayals of ordinary and often anonymous Americans and for their unsentimental depictions of poverty. became so established that it developed its own sub-genres, such as (following Lange's iconic Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936)) the "Madonna and child" trope that showed a self-sacrificing mother caring for her suffering children.

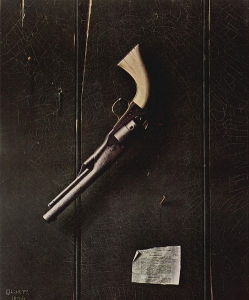

The Still Life

Influenced by seventeenth-century Dutch and German painters, American still lifes from the latter half of the nineteenth-century often employed the trompe-l'oeil (illusion of reality) method. These works were hung, not in galleries, but rather in business premises and taverns. Their theme was typically masculine, with the so called "bachelor still lifes" featuring images of weaponry, cash, smoking, drinking and hunting. Artists such as Raphaelle Peale, William M.Harnett, John F. Peto and John Haberle were quickly forgotten after their death; their work not given the respect accorded the best landscapists of the period. But the canvases have an important place in the history of American Realism. Although dismissed as novelties by the critics, the trompe-l'oeil paintings were very popular with the public in their time and, when they were re-evaluated by later generations, they commanded a new respect. Indeed, in the 1970s and 1980s, Photorealists such as Ralph Goings and Audrey Flack produced precisely-rendered trompe-l'oeil effects in paintings that showed elements of Americana with such accuracy they were at first glance hard to distinguish from photographs.

Later Developments - After American Realism

The 1940s and 1950s saw a seismic shift in direction for American Art. The rise of Abstract Expressionism saw all forms of figuration dismissed as passe. As the political climate changed domestically and internationally, Realism suddenly seemed terribly outmoded. Abstract Expressionism was seen as a symbol of creative leadership in the fine arts that matched the political and cultural supremacy America had achieved in the Post-War years. A handful of Realists stood their ground, however. From 1943, the Magical Realists began producing paintings that were realist in style if not content. Influenced by European Surrealism and German Neue Sachlichkeit, artists such as Peter Blume, Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and George Tooker adopted a counter position to Abstract Expressionism. Indeed, in the 1950s, led by Raphael Soyer, a group of artists including Hopper, Shahn, Bishop, Leon Kroll and Yasuo Kuniyoshi lobbied museum directors in defense of their art and championed human qualities in painting.

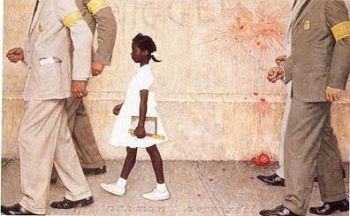

Later, two artists offered a further antidote to the dominance of Abstract Expressionism: Andrew Wyeth and Norman Rockwell. Wyeth's bleak images, which were heavily influenced by photography, took ordinal subjects and imbued them with a psychological tension. Rockwell, of course, became the nation's most popular artists and, for that "crime", was widely dismissed by critics (including the infamous Clement Greenberg) for his sentimental and nationalistic Saturday Evening Post covers. However, Rockwell, especially in his later career paintings for LOOK magazine, was given to promote "causes" such as the freedom of speech and the Civil Rights movement. In The Problem We All Live With (1964), for instance, he pictured Ruby Nell Bridges, a six year old African American girl, being escorted to her newly desegregated New Orleans school on her first day by four US Marshals. Rockwell had prepared the image by taking photographs of legs walking in order to capture the patterns of folds and creases in the pants of the Marshalls.

Rockwell in fact traveled to Russia (and other European destinations) with the intent of studying Socialist Realism. There he made sketches of Russian school children which he used later for a LOOK magazine cover painted in a photo-realistic style. Indeed, Photorealism (or Hyperrealism or Super-realism) saw other 1960s artists developing a more highly polished and exaggerated style to depict real and still life. Artists such as Chuck Close, Malcolm Morley, Charles Bell, Ralph Goings and Robert Bechtle projected photographs onto canvas allowing images to be replicated with precision and accuracy. The 1960s also saw a new group of New York artists return to figuration in direct defiance to the prevailing popularity of Abstract Expressionism. Artists such as Jane Freilicher, Alex Katz, Leland Bell, Nell Blaine, William Bailey and Larry Rivers all produced works that earned the label: Contemporary Realism.

In 2020, the periodical Art in America devoted an issue to the theme of "Realism and Revivalism". In his editorial, William S. Smith spoke of a "resurgence of figurative painting" that was both "pluralistic and contentious" and encompassed a cadre of young artists ranging from Jordan Casteel and Aliza Nisenbaum to Amy Sherald and Titus Kaphar. He wrote, "contemporary painting has become a vital force within the culture at large" and that "at a moment when there is widespread attention to racial inequities in the United States, figurative artists like these are representing people who have long been excluded from the canon". He adds that "If oil painting is old fashioned, that's exactly the point: the choice of medium is part of an argument about who can be represented in the most time-honored fashion". The likes of Casteel and Nisenbaum, he continued, are, "like their photographer and filmmaker peers [...] recording the profound transformation of labor conditions in the twenty-first century [and that through] its many revivals and its many guises, realism appears most vital during periods of social change".

Useful Resources on American Realism

- American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885-1915By Barbara Weinberg

- American RealismOur PickBy Edward Lucie Smith

- From Hopper to Rothko: America's Road to Modern ArtBy Ortud Westheider

- The Hudson River School: Nature and the AmericanVisionBy Linda S. Ferber

- Ten Jaw Dropping Works Of HyperrealismBy Lily Cichanowicz

- Social realism: Art as a Weapon (Critical studies in American art)By David Shapiro and Irving Perkins

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI