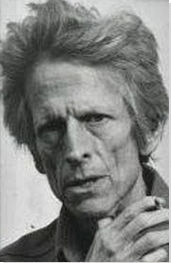

Summary of David Hare

An American artist adopted by the exiled French Surrealists during World War II, David Hare created photographs, sculptures, paintings, and collages that probed the depths of the human psyche and condition. Eventually steel and bronze became his preferred materials as he created hybrid forms that came from dreams and memories and that evoke uncanny feelings in the viewer. Immersed in Surrealist philosophy but friends with the burgeoning Abstract Expressionists, Hare's sculpture is unique in its concreteness; not a representation of a dream exactly or an abstract symbol, Hare's sculptures seem to take on a life of their own.

Perhaps because he straddled two movements and split much of his time between the United States and Paris, Hare's work doesn't fit neatly into any one category. His overriding creative guidance was that, in his words, "a work of art breaks up reality and recombines it in such a manner as to enlarge our understanding of a total life." Though successful during his life, Hare was not much of a self-promoter and his work is not widely known today. His commitment to Surrealist explorations of human desire, death, and love, even after such subjects fell out of favor, is a testament to the idea that throughout time artists have created art from probing their own psychic spaces and memories.

Accomplishments

- Hare's metal sculptures follow in the line of Surrealist biomorphic sculpture, which uses abstract shapes and forms to create organic compositions that evoke various emotional associations. Though not exactly like using found objects, Hare's use of familiar shapes, often taken from nature, is a form of automatic process that invites randomness and intuition over reason and predetermination.

- Hare used fantastical imagery and mysterious forms to engage the viewer. By creating hybrid figures that at once seem familiar but not quite recognizable, Hare taps into the viewer's imagination, allowing them the freedom to explore their own emotions, desires, and memories in relation to the forms in order to create their own dreams and stories.

- While primarily known as a sculptor, Hare explored Surrealist creative processes in an array of mediums that made him unique among his New York peers. Manipulating negatives, employing automatic drawing and free association, Hare embraced Surrealism's non-traditional methods that downplayed the role of artistic genius.

Important Art by David Hare

Untitled (from VVV portfolio)

This photograph is an example of David Hare's early experimentation with photography and notably with the technique of heatage, or brulage, developed by Surrealist Raoul Ubac. It consists of heating up or melting parts of the photographic negative during the development process, which causes the negative to ripple and distort. The result is a random deformation of the image. The chance-like nature of the technique appealed to the Surrealists and was comparable to other favored techniques like automatic drawing.

In this photograph, only the contour of a naked female body remains. The anatomical details have been replaced with alternating black and white masses. While the pattern is abstract and devised by chance manipulation, the effect conjures burnt flesh. The lack of facial features further accentuates the strangeness of this woman.

For his photographs, Hare usually chose female nudes and transformed them, playing with ideas of eroticism and censorship. The suggestive pose of the figure contrasts sharply with the metamorphosed body, creating a feeling of uneasiness and discomfort in the viewer. Art historian Phil Taylor explains that Ubac and Hare both use heatage in order to negate "the capacity of the photographic matrix to reproduce its original referents." Instead of reproducing an objective, or realistic, scene, Hare disrupts photography's illustrative powers to create something new.

In the context of the second World War, this technique takes on a subversive and political cast. The disintegrating figure is associated with a body mutilated by the violence of war. Gilbert states, "Hare's images opposed the aim of government censorship to control and sanitize the visual experience of war." He adds, "Hare's technical assault on the medium is itself significant and reflects a radical effort to subvert the documentary status and truth value of the official media's photographic reportage." In embracing Surrealist techniques, Hare did not shy away from the radical and, at times, revolutionary underpinnings of the avant-garde group.

Gelatin silver print - Ubu Gallery

Magician's Game

Hare created this artwork in response to the gallerist Julien Levy who decided to curate a show about chess, a board game that he and many of his artist friends like Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst loved playing. Levy had designed his own set and asked 32 artists to contribute to his show that opened in the winter of 1944. Hare exhibited the plaster original of Magician's Game that he would cast in bronze in 1946.

The sculpture is a combination of shapes that resemble both animate and inanimate objects and suggests a slightly reclined figure sitting at a desk or game table. An egg-shaped object dangles in one of the desk's compartments, and from the other a stick emerges and from which comb-shaped form hangs. The reclining shape pierces the surface of the desk, suspended in the void by wires and, when pushed, quivers slightly and counterbalances the composition. This figure extends and connects itself under the desk with what appears to be a pointed tail.

Art Historian Mona Hadler describes this sculpture as epitomizing the Surrealist process of "free association of disparate ideas." Indeed, Hare combines many objects and shapes and creates a strange figure that seems to float in space. The figure is a hybrid entity, somewhere between a living creature and an inanimate object. It has no human attributes, except maybe the chest, but at the same time, it is clearly seated at a desk surrounded by human objects. Further the unrecognizable nature of the "game" adds another layer of mystery that draws in the viewer. The viewer is led to create the game in their own mind. Hadler points out that Hare has always wanted the viewer to actively participate, even in the act of literally moving the work. She explains, "The complexity and multiplicity of imagery of Hare's sculpture force an active process of viewing." The tensions that Hare's sculpture creates - animate/inanimate, stabile/mobile, seen/unseen, reality/fantasy - keep the viewers engaged.

Bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Sunrise

This sculpture is part of a series that Hare created in the 1950s and that integrated elements of the natural landscape. The artist believed that art should have some relation to the physical world and not be entirely abstract. This work consists of a sun-like form at the top held by steel rods over a rock. There are also two other round forms between the sun and the rock that could represent a moon and a star. The vertical straight fragments of steel evoke lines of falling rain.

When asked in the 1960s by the Albright Knox Museum "Why would you sculpt a sunrise?" the artist answered that the main point "was first to make a sculpture from a subject which seemed highly unlikely as a sculptural material, the interest being in this being the difficulty of the problem and also its newness." Like his colleague David Smith, Hare appropriated a traditional subject of painting, but by welding the picture, he was able to make "drawings in space" and to create open and airy sculpture. Hare further explained about this work, "I wanted to take a picture of [the planet] before it disappeared." However, the artist also wanted to create a piece "that could be seen as abstract or as figurative," making this very tension the work of art itself.

Steel, rock, gilt bronze solder - The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

The Swan's Dream of Leda

Hare used thin, irregularly sized sheets of bronze to compose The Swan's Dream of Leda. From a rock, a central, vertical shape emerges and bends back as if looking up. Another curved figure hovers over, enveloping and seemingly piercing the central figure. This sculpture refers to the Greek myth of Leda in which the god Zeus transformed himself into a swan to seduce the woman he so desired, eventually impregnating her. The gentle and slender curves along with the empty spaces of the composition gives an impression of lightness in spite of the use of bronze. The fragile and delicate forms contrasts with the strong rock base as well. The arched form seems to replicate the flapping of a swan's wing.

Hare started his series on the myth of Leda as early as the 1950s and would explore it until the end of his life. For many Surrealists, mythology is significant because of its relation to the psyche and for its aim for universality. The story of Leda has been explored many times in the history of art, but Hare, as many specialists have pointed out, is the only artist who shows how the swan sees Leda. This unconventional point of view allows him to give more depth to the character of the bird and to introduce the theme of the dream. Hare could have treated the myth in a more explicit and representational way, but by abstracting the subject and only loosely suggesting the identities of the figures, Hare captures the dream-like nature of the story.

Bronze with stone base - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Cronus Grown

This painting is part of the series that Hare started in the 1950s exploring the Greek myth of Cronus, who upon castrating and deposing his father Uranus, separated heaven and earth and became ruler of the cosmos. In fear of a prophecy that he would in turn be overthrown by his own son, Cronus swallowed each of his sons as they were born. His wife Rhea managed to save Zeus who would eventually murder his father and defeat the Titans. The Romans adopted Cronus as the god Saturn.

In a composition that recalls optical illusions, it is difficult to know what one is looking at in this painting. Hare manipulates shadow and light, foreground and background to create a sense of disorientation. A peachy, flesh colored form protrudes from the center of the canvas, and one wonders if this is the legs and crotch of a splayed body or two giant fingers reaching out from a hand as it clutches an amorphous brown form in the foreground. Above the body/hand a dark blue shape seems to swirl, forming tendrils at its edge that are evocative of fingers and even a small silhouette of a person. Behind, shades of brown, grey and cream create a sort of non-space that could be the sky or an interior of a room. The abstract scene evokes a sinister and, even, horrific sense of doom or danger.

Hare came late to painting and was primarily known as a photographer and sculptor, but his technique was still grounded in Surrealism, and his uses of collage and automatic drawing creates a dream-like space that draws the viewer in and confounds them. In an interview with Mimi Poser in 1972, Hare declared that his images of Cronus are portraits of the human will. The series exemplifies the contradictions of love/hate and life/death that are inherent to human kind. Like Cronus, humans continually destroy what they love. This painting captures the most violent and symbolic moment of the myth without monstrosity.

Acrylic, collaged paper, and oil stick on linen - The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Cronus Hermaphrodite

A contorted body fills the center of the composition. The head of a bull sits atop a male torso. One follows the line of the back down to the buttocks and up to the bent knees, and along the way, the body twists unhumanly in space to reveal female genitalia. To the left, one expects the figure to be resting on its arms but instead one finds a shape that is reminiscent of male genitalia. The mysterious creature also has across its torso, two spoked circles, almost like tattoos, and an array of small dots where one expects there to be nipples. These cryptic motifs further add mystery and magic to the hybrid creature.

Portraying Cronus with both male and female genitalia underscores the duality that so intrigued Hare about this mythological figure. Although Cronus does not often call for a sexual interpretation, Hare adds it to his exploration to create an even more universal figure. He declared, "Cronus is part man, part earth, part time." Based on a 1970 painting of the same name, Hare executed this print at the Tamarind Institute. Hare was interested in the lines and forms of lithography and created several prints based on paintings of the Cronus series, in which he further explored his Surrealist inclinations to portray the human psyche.

Four-color lithograph

Biography of David Hare

Childhood

David Hare was born on March 10, 1917, in New York City into an affluent family. Hare's mother, Elizabeth Sage Goodwin, called Betty, was a renowned art collector from a wealthy family active in avant-garde art circles and a friend to artists, including Constantin Brâncuși and Marcel Duchamp. In 1913, she was among the patrons of the famed Armory Show that featured advanced European modern art to a large American audience. Hare's uncle, Philip Goodwin, was a trustee and the original architect of the Museum of Modern Art. His father, Meredith Hare, was a prominent corporate attorney, who supported all of his wife's activities. Betty was a generous benefactress of social issues, museums, and individual artists. As a result, Hare was exposed to art early in life and grew up in privileged circles of New York and Washington D. C.

In 1926, when he was 10 years old, Hare's father contracted tuberculosis. The family moved to the healthful climate of the high desert of the Southwest. The artist spent much of his free time in the mountains and deserts of the West and befriended the Pueblo Indians who lived nearby. The family finally settled in Colorado Springs. To give David a good education, Betty founded the Fountain Valley School of Colorado. Unfortunately, in 1932, Hare's father succumbed to his illness. Hare's mother decided to stay in Colorado while he finished high school. When the artist finally graduated in 1936, he and his mother returned to the East Coast. Betty would eventually go back to the West Coast and stay in Santa Fe, where she would contribute to the vibrant art community that flourished there.

Early Training and Work

Back in New York, Hare began to study chemistry and biology at Bard College in the Hudson River Valley, and he began to take interest in photography as a hobby. After six months in college, he dropped out and returned to the city, setting up a commercial photography studio. His first assignments were for magazine and newspaper advertisements. Then, he opened a portrait studio. With his mother's network and influence, he secured commissions from notable public and private figures. Betty also introduced him to Susanna Perkins, daughter of Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration. David and Susanna fell in love and married in March 1938. Hare purchased a home in Roxbury, Connecticut, and they split their time between there and New York. Many famous artists had settled in Roxbury, and the couple soon befriended the sculptor Alexander Calder, who had lived there since 1933.

After a solo show at the Walker Galleries in 1939, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City commissioned from Hare a series of color portraits of Pueblo peoples. Having lived in the West, he was still friends with several Puebloans, so he went back to Santa Fe for some time to complete the project. Hare produced 20 prints using the new dye transfer process of Eastman Kodak. He chose to photograph the Native Americans in their everyday dress, often a combination of traditional and Anglo-influenced clothing.

After completing this project, Hare returned to commercial photography and began to experiment with the medium. He tried to perfect various color techniques and manipulated the negatives, finding surprising results. Fellow photographer Milton Gendel explained, "He would use flame to alter his negatives so that the forms portrayed would become mysteriously indeterminate, with the blacks and whites dissolving and melting into each other." He may have been aware of the experimental work of Man Ray, Raoul Ubac, and Wolfgang Paalen who were doing similar experiments with photography. In 1940, Julien Levy gave him a solo show in his gallery. Levy described Hare as "brilliant, taciturn, and full of promise."

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, many artists fled Europe for the United States. Hare, in 1940, found himself involved in bringing many Surrealist artists to America. Kay Sage, the Surrealist painter married to Yves Tanguy and Hare's cousin, began raising money to help artists escape the war. Hare, along with his wife Susanna Perkins and her affluent father, quickly found American sponsors, including Peggy Guggenheim, to bring the exiled artists to the United States. Hare and his wife sponsored the so-called pope of Surrealism, André Breton, himself.

Hare quickly developed a strong friendship with the newly-relocated group of Surrealists, and they accepted him as one of their own. He was enthusiastic about their ideas and quickly embraced the principle of automatism in his own creative practice. For American artists at the time, the Surrealists were a significant and liberating influence.

In 1941, Hare participated in the publication of Breton's Surrealist magazine, VVV, shorthand for Victory, Victory, Victory, designed to promote Surrealism in America. Because American laws prevented Breton, a foreigner, to be the only director of the publication, the Frenchman asked Hare to serve as co-director and editor. The magazine was devoted to "poetry, plastic arts, anthropology, sociology, and psychology." Contributors to the publication hailed from all over the world and included Robert Motherwell, Aimé Césaire, Giorgio de Chirico, Yves Tanguy, and Roberto Matta, among others. As Robert Motherwell remembered, however, "Although David Hare was the editor, Breton maintained strict control of the content." Hare would later corroborate and comment that Breton always had the final word on everything. Infamously, Breton refused to learn English, and his wife, the artist Jacqueline Lamba, served as the translator between Breton and Hare. All in all, only three issues were published between June 1942 and February 1944, but the magazine gave great exposure to exiled Surrealist writers and artists. In addition, it was a bridge between the European movement and a growing number of emerging American artists.

Jacqueline Lamba played a key role in initiating Hare into the language of Surrealism and its possibilities. The two artists fell in love while working on VVV magazine. According to one of their friends, Hare "fell head-over-heels in love with her the first minute he saw her." She was indeed a very beautiful and attractive woman who inspired Breton's famous novel Mad Love. Hare and Lamba married in 1942, and she, along with Aube, the 6-year-old daughter that she and Breton had together, went to live with Hare in Roxbury.

Lamba recognized Hare's talent and encouraged him to make sculpture seriously. "You are good with your hands," she told him often. By this time, he had met and befriended many sculptors, including Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi, who shared their vision and techniques with him. Close friends Arshile Gorky and Roberto Matta also educated him about sculpture as it was developing then in Europe. With all these new ideas in mind plus his knowledge of Native American art, Hare created original sculptures inspired by Surrealist forms, motifs, and techniques. Well-received in New York art circles, Hare won a reputation as one of the most promising sculptors of his generation.

Mature Period

With his Surrealist sculptures, Hare's career grew rapidly successful. Hare combined human, animal, and mechanical forms to create hybrid creatures. He exhibited in First Papers of Surrealism exhibition organized by André Masson to announce Surrealism in America in 1942. In 1944, Peggy Guggenheim gave him his first solo show at Art of This Century Gallery. She said that Hare was "the best sculptor since Giacometti, Calder, and Moore." After Jackson Pollock, Hare would be the second artist most exhibited in the gallery's short history. In 1946, Clement Greenberg wrote, "Hare stands second to no sculptor of his generation, unless it be David Smith, in potential talent." The artist had many solo shows in prominent galleries in New York, including the Samuel Kootz and Julien Levy Galleries.

During this time, Hare befriended French writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and was introduced to the philosophy of Existentialism, which did not entirely meld with Surrealist ideas. The artist nevertheless contributed to Sartre's Parisian publication, Les Temps Modernes, and collected American manuscripts and articles for the magazine. The artist wrote two essays for a 1946 issue devoted to America and American writers.

When the war finally ended in 1945, the exiled artists began to return home to Europe. Many of Hare's Surrealist friends departed the United States, but they left in their wake a group of inquisitive, serious American artists who were ready to show the world what new artistic expressions they were capable of creating. Subsequently, in the years following the end of the war, the center of the art world shifted from Paris to New York as more artists, critics, and eventually collectors began to take notice.

In 1948, Hare, along with artists Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and William Baziotes, founded the Subjects of the Artist school, an informal educational space for artists to create and connect. Aspiring artists were able to work with guidance and input from the founding artists, and a series of Friday evening lectures by advanced artists was attended by students and artists alike. Many of the speakers were allied with Surrealism, but other artists including Willem de Kooning, Fritz Glarner, and John Cage also spoke. After two semesters, the school closed due to financial pressure, and the space was taken over by artists and educators from New York University and renamed Studio 35 (after its street address at 35 E. 8th Street). Shortly thereafter, another artists' space - The Club - opened next door and Friday night lectures resumed, creating a forum that proved to be crucial for the birth of Abstract Expressionism.

While he was playing his part on the New York art scene, Hare also travelled to France with his wife and tightened his bond with European art. In 1947, they went to Paris to attend the opening of the Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme at the Galerie Maeght where the couple showed several pieces. That same year, Hare was the object of a solo show at Maeght. Sartre wrote the introduction of the catalogue and stated, "David Hare has found his personal way of solving the conflict between space and idea." The couple returned to New York, where Hare continued having solo shows. In June 1948, Lamba gave birth to their son, Meredith Merlin Hare, likely named after the wizard of the Arthurian legend that some Surrealists cherished as a source of inspiration. Beginning in 1948, Hare and Lamba started living between Europe and America for about six years. In France, Hare met new artists like Balthus, Victor Brauner, Alberto Giacometti, and Pablo Picasso. Hare was exposed to new artistic developments in Europe and started to use steel and bronze and to incorporate found metal objects in his works like Jean Dubuffet. Exhibited under the label Abstract Expressionists, Hare along with Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, and David Smith were selected for the first São Paulo Biennial in Brazil in 1951.

Hare was constantly working and meeting new people, but his relationship with Lamba was deteriorating. Their close friends, the sculptor Ibram Lassaw and his wife Ernestine, recalled Hare's many girlfriends and his experimenting heavily with drugs. Hare and Lamba separated many times until 1955, when the couple finally divorced. Merlin, then 7, stayed with his mother in Paris.

The following year in 1956, Hare met Denise Browne, a photographer and filmmaker. They soon started a romantic relationship and divided their time between Greenwich Village and Wyoming, where they purchased a ranch. In New York, Duchamp and his wife Teeny, Saul Steinberg, Hedda Sterne, and Harold Rosenberg were among their regular guests. Hare spent his time working as usual, experimenting with new ways of making sculpture. In 1961, Browne bore their son Morgan, and she and Hare married in 1962, with Duchamp acting as the best man.

Late Period

In the early 1960s, at the height of his renown as a sculptor, Hare felt he was becoming repetitive. After a self-review period, he decided to turn to painting. He stated, "I really didn't want to stop making sculpture - it wasn't that I lost interest in sculpture, but I got tired of being limited to an object." Hare increasingly felt that the process of welding and casting slowed him down, and he wanted to give more spontaneity and immediacy to his ideas. Along with paintings, he made many drawings and collages. The sudden shift was not welcome by his gallerist Samuel Kootz, but Hare did not comply with market demands and kept taking risks. Kootz refused to show Hare's new body of work, asserting that the new direction would confuse the public. Hare had no choice but to leave the gallery and went on to join the Saidenberg Gallery.

Devoting himself to the new medium, Hare painted mythological subjects as well as abstract landscapes, and incorporated collage elements into his canvases. Despite the switch in mediums, Hare did continue to experiment with sculpture. New imagery appeared in his works, and in 1970, over the course of more than a decade, Hare worked through again and again a series of paintings, drawings, and sculptures based on the myth of Cronus in order to explore the contradictory impulses of humanity. In 1977, these works comprised a solo show at the Guggenheim Museum, which Rosenberg declared as one of the most significant shows of the year.

During these same years, Hare's marriage grew more and more difficult and eventually ended in divorce in 1978. Artist Lee Krasner commented that Hare was one of those men who "treated their women like something you dreamed up and put on exhibition."

He continued experimenting and working across mediums, and his works were exhibited widely throughout Europe and America. Since the 1960s, Hare also taught at various institutions, including the Maryland Institute of Art in Baltimore and at the New York Studio School, and he lectured widely on Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. In 1969, he received an honorary doctorate from the Maryland Institute of Art, a pleasant twist as he was a self-taught artist.

After the 1977 Guggenheim show, Hare retreated out of the public eye. In 1985, he moved to live in the wilderness of his new Idaho home in the town of Victor. He built a studio in the hayloft of a converted barn and worked there most of the time. As gallerist Rowland Weinstein explained, Hare "felt content in the last decades of his life to paint and sculpt as his own vision commanded, leaving the task of a full understanding of the work to later generations." He married again in 1991 with Therry Frey, a Swiss journalist who interviewed him in 1979. On December 21, 1992, Hare died after an emergency operation for an aortic aneurysm. He was 75 years old.

The Legacy of David Hare

David Hare was quickly recognized as an innovative sculptor linking Surrealism and the new American avant-garde. Clement Greenberg declared, "Hare has already shown enough promise to place him in the forefront of what now begins to seem, not a renaissance, but a naissance of sculpture in America." Over the years, he was included in many groundbreaking exhibitions in America and in Europe, and eventually his works were selected for several historically important exhibitions, including the Museum of Modern Art's 1968 retrospective survey of Surrealism's impact: Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage.

Though successful during his lifetime, Hare was never able to shake the label of Surrealism and never fit easily within Abstract Expressionism. Despite efforts by several art historians, notably Mona Hadler, to reassess Hare's work and career, he is still mostly known today as an American sculptor related to Surrealism. As art critic Holland Cotter stated in 1994, Hare "got left behind in time, frozen in a style that many of his colleagues moved beyond." Even if Hare's influence is not felt directly, Surrealism's reach continued through the 1960s in various guises including Louise Bourgeois' sculptures and Joan Jonas' performances, and even today, artists such as Robert Gober and Sarah Lucas play with Surrealist ideas and tropes.

Influences and Connections

-

![Harold Rosenberg]() Harold Rosenberg

Harold Rosenberg -

![Hedda Sterne]() Hedda Sterne

Hedda Sterne -

![Ibram Lassaw]() Ibram Lassaw

Ibram Lassaw ![Saul Steinberg]() Saul Steinberg

Saul Steinberg

Useful Resources on David Hare

- David Hare: American Surrealist. January 8-31, 2015By Alan Wolfsy Fine Arts

- David Hare: Cronus, elephants, flying heads : [exhibition] November 18-December 16, 1983, University Art Gallery, State University of New York at BinghamtonBy University Art Gallery, State University of New York at Binghamton

- Shaman's Fire: The Late Paintings of David Hare, 1998By Greenville County Museum of Art

- Surrealist painters and poets: an anthology, 2001Edited by Mary Ann Caws

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI