Summary of Street Photography

Associated initially with Paris, and figures such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Brassaï and André Kertész, Street Photography became recognized as a genre in its own right during the early 1930s. While there are precedents, and areas of overlap with documentary and architectural photography, Street Photography is unique in the way it is associated with the photographer's skill in capturing something of the mystery and aura of everyday city living. As such, the human figure becomes the Street photograph's most vivid and defining feature. Street Photographers will sometimes engage directly with their subjects (Brassaï, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand) but it became more common for the photographer to roam the streets with a concealed 35mm camera. The Street Photographer is then often likened to the historical figure of the flâneur: namely someone who mingles anonymously amongst the crowd observing and recording the ways the unsuspecting city dweller interacts with his or her environment.

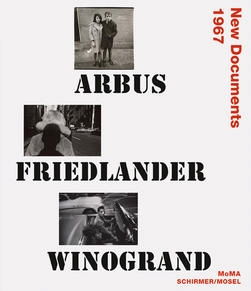

While the early French pioneers formed close associations with the Surrealists, the improvisational quality that embraces the uneven and spontaneous Snapshot Aesthetic carried across the Atlantic where it lent itself perfectly to the post-war urban experience. Possibly the most important Street Photographer of all, the Swiss-American Robert Frank, raised the status of the Snapshot to art and his influence was to enthuse the next generation of American photographers. The mid-1960s and early-1970s became the "golden-age" of Street Photography when the likes of the Arbus, Winogrand and Lee Friedlander allowed their own sassy personalities to impinge on the images of their subjects. Joel Meyerowitz completed this new dynamic by raising the status of color, hitherto thought of as somewhat artless and vulgar, to a new level of credibility.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Street Photography tends to be spontaneous and seeks to capture a moment - or a split second - that would have, without the photographer's intervention, gone unnoticed. It is closely associated with a Snapshot Aesthetic which describes a technique in which a loose and informal composition brings an intense energy and a new truth to the image.

- Street Photography emerged as a genre in its own right as a direct result of advances in camera technology. It is associated (if not exclusively so) with the hand-held 35mm camera and especially the emergence of the very compact Leica and its superior lens quality.

- Street Photography can certainly qualify as Documentary Photography, yet documentary asks for a different type of intention from that of the Street Photographer. The documentary photographer tends to be less spontaneous, more prosaic, in their approach with the documentarian invariably using his or her lens to expose social injustices or involved stories.

- Though there remains a strong lineage to documentary, street photography tends to position itself as art. Street Photographers want their audience to think more profoundly about the meanings behind the images they produce.

- The latter-day Street Photographer is typically possessed of a particular attitude; someone who sees their art as a calling or vocation. Street Photography is as much about a "state of mind" and a Street Photographer is someone who tends to treat their camera as a constant companion.

Important Photographs and Artists of Street Photography

Place de l'Europe

This iconic image depicts a man skipping (with a true sense of Parisian élan) over a flooded area in the Place de ;'Europe, just outside the Saint Lazare train station. The photograph illustrates Cartier-Bresson's "decisive moment" technique - described by him as that "one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance" - in the way his camera freezes the exact moment the prancing man touches heels with his reflected image. Cartier-Bresson was inspired by the Surrealists and we see that influence too in the surrealistic preoccupation with the idea of the uncanny doppelgänger (revealed in the man's reflection). The surrealistic mystery of the man's flight is only strengthened by the "floating" ladder from which he appears to have sprung while the shadowy onlooker in the middle-distance merely completes the image's element of incongruity.

Beneath the chimney in the upper left of the frame, meanwhile, a circus poster shows a female dancer in a pose that copies that of the main subject. The superior lens quality of the Leica camera would lend the image a potential for fine picture detail such as this to emerge. It is also of some significance (for the idea of photography as an art form in its own right) that Cartier-Bresson's figurative juxtaposition is set against a hazy background of Saint Lazare. These buildings had been painted previously by the likes of Monet and Manet which suggests that the photographer wanted to invite associations, not just with the Surrealists, but with the great masters of French modernism.

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Bijoux de Montmartre, Bar de la Lune

Playing a significant role in creating the bohemian image of Paris, Brassaï photographed the artists, socialites, prostitutes, and philosophers who populated the streets, parks, and bars at night. This image, featured in his famous book Paris by Night, depicts a mature woman - La Môme Bijou ("the urchin Bijou"), or Miss Diamonds, as she was variously known within the Montmartre community - sitting alone in a bar with a wine glass and two stacked small white plates on the table before her. She wears a hat with a flower and a fur-collared coat (despite being indoors) and several strands of pearls around her neck. Described by Brassaï as "the queen of Montmartre's nocturnal fauna [and a] fantastic apparition that had sprung up out of the night," she carries a fading image of a glamorous past.

Though his images featured people who lived at the forgotten margins of society, Brassaï brought a kind of poetic reverie to his images: "I was seeking the poetry of the fog which transforms people, the poetry of the night which transforms the city" he said. Bijou with her faded glamor embodied the La Belle Époque ("the beautiful era") in France, but, despite clinging to the past, she retains a distinctive presence, as her knowing gaze shrewdly evaluates the scene before her. As a further measure of Bijou's presence, the protagonist of the French Jean Giraudoux's play The Madwoman of Chaillot (1945) was inspired by this photograph.

Gelatin silver print - The John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

New York (Children with Broken Mirror)

In the 1930s Levitt began taking the photographs of children at play in the streets of New York, for which she is best known. Influenced by Walker Evans and Cartier-Bresson, her photographs combine the objective humanism of Evans with Cartier-Bresson's emphasis on the "decisive moment" and, like Cartier-Bresson, her work was influenced by Surrealism's interest in exploring the idea of the uncanny.

In this photograph, two children hold up a broken mirror as two others crouch, examining the glass shards around the curb. Behind the frame a little boy on a bicycle surges forward, as if he is about to pitch through the frame itself. At first glance, it seems that the boy on the bicycle is a pictorial incongruity. Only upon closer reflection does the spectator realize that the mirror is broken, and that the boy pitching forward is (potentially) about to emerge through the empty frame. A further examination of the image requires an adjustment of the spectator's imagination since she or he realizes that the boy on the bike is in fact stationary and has stopped to see what the boys on our side of the frame are doing. As a result, the image's play upon the mirror becomes a play upon the nature of photographic reality itself and the part the viewer's imagination plays in forming that reality.

Silver gelatin print - Whitney Museum, New York

Lower East Side

This photo depicts a middle-aged woman standing astride her steps, her powerful body leaning emphatically as she points aggressively outside of the picture's frame, her mouth curled angrily around her words.

Born in Austria, Lisette Model first became known for the often brutally revealing photographs she secretly took of wealthy vacationers in Nice in 1934. In 1938 Model moved to New York City and in 1951 she began teaching at the New School for Social Research where she taught and influenced photographers like Rosalind Solomon, Larry Fink, and most notably, Diane Arbus.

Before turning to photography, Model had studied music with the composer, Arnold Schönberg, and Expressionism's emphasis on conveying often dark emotional reality continued to influence her frank images of iconic characters. Closely cropped, the woman fills the frame, and the diagonals of the step's railing and the angle of her coat exaggerate the emotion expressed in her body language. The shot, taken from a low angle, makes her appear to loom over the street like a fury of scolding chastisement.

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fall 1953, New York

In Maier's image, a fashionable middle-class woman, with a parcel and her purse on one arm, looks on at an incident to her left where a policeman is helping a man bent on crutches into the entrance of a building. In the middle left an older man has paused to survey the scene as well.

Throughout her life Maier worked as a nanny and the 150,000+ street photographs she took remained unknown to the public until the age of social media dawned. In 2007, two years prior to her death, she was unable to pay the rent on a storage locker and the contents, which included her negatives, prints, some 8mm film, and audio recordings, were sold to three collectors. In 2009 one of the collectors, John Moloof, linked a Flickr page of her images to his blog and Maier's work became a viral sensation, resulting in international attention for her work, and an acclaimed film: Finding Vivian Maier in 2013.

Maier often used a Rollieflex, a larger camera that, while, allowing for finer detail, made the subject often aware the photograph was being taken. As a result, one of the themes of her work is how the observer is simultaneously observed, as can be seen here as a man, only partially visible at the far right, turns to look at the photographer with the same look that the woman, passing by, directs toward the trio at the door. A number of her images are self-portraits, caught in the reflection of a shop window or mirror, and in this work too, the solitary woman observer passing by becomes a kind of allegory for the photographer.

Silver gelatin print - Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

New York City

While working on assignments for Harper's Bazaar, Frank made the acquaintance of the Russian art director and photographer, Alexey Brodovitch and it was the Russian who encouraged Frank to pursue his creative goal of developing a new and authentic photographic art. Brodovitch urged his mentee to take greater risks in his work and emboldened Frank to "unlearn" the studio practices he had learned since his time as a young apprentice in his Swiss homeland and to venture out onto the streets and highways of his adopted land (America).

New York City, a photograph that is part of Frank's seminal The Americans photobook, captures a group of striking white workers on a New York sidewalk. We can see in the foreground a working-class African-American man slouched against a trashcan. He appears to be carrying a giant American flag - something of a motif throughout The Americans project - though on closer inspection we realise that this is in fact an optical illusion. The "flagbearer's" demeanour - arms folded across his chest, his gaze turned towards an object or events outside the frame, and away from the protesters - suggests an indifference towards the plight of the white workers. Though the subjects belong to the same social class, the image alludes to a contradiction by presenting a picture of a conflicted ethnic society rather than that of "one nation" united under the same flag.

Photograph on paper - Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, California

New York World's Fair

Winogrand stated (in a discussion about this image in particular) that the "problem" facing the Street Photographer was "How do you make a photograph that's more interesting than what happened"? In other words, the quest of the Street Photographer was to elevate the everyday to the status of art. Here, Winogrand's off-center snapshot features six women and two men who share a municipal bench during New York's World Fair of 1964-65. Save the middle-aged man on the far right who is reading a newspaper, the subjects are energetically absorbed in their own private conservations and are clearly oblivious to Winogrand's presence.

The image amounts to more than documentary and/or nostalgia by virtue of the fact that the meaning of the image is potentially ambiguous. With the only clue to its meaning being the photograph's title (which gives us a time and place) the spectator is invited to use their imagination in bringing their own reading to the picture. However, the timeless allure of finding the image's true meaning was emphasized some fifty years later, in 2014, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art featured a retrospective of Winogrand's work. In conjunction with the exhibition, the museum tracked down two of the women, Karen Marcato Kiaer (third in from our left) and Ann Amy Shea (fourth in from our right). In an exchange of emails (published in The New Yorker) Ann confirmed that the six women were classmates from a small city college called Duchesne Residence School. The school's headmistress had provided tickets for the girls to attend the World's Fair. Karen recalled: "We college girls lived together on the sixth floor of the convent school [and] were celebrating, that day at the fair, knowing school was finishing up for the year, and looking forward to being part of the freedom movement and spending the summer in Shreveport, Louisiana, doing voter-registration work." However, the idea that Street Photography could appear on the hallowed walls of an art gallery was met with incredulity by Ann who supplied the following comment: "Girls will be girls - we were kidding with each other and those around us. I never saw a photographer, or anyone taking our picture [...] We were just a bunch of girls out having fun. Why would anyone take our picture"?

Gelatin silver print - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

New York City

This photograph marks a crucial point in Meyerowitz's career. In this period during the mid-1970s, Meyerowitz switched from a small handheld camera to a large format 8 x 10 Deardorff. The loss of mobility is however compensated for by the much larger, high quality color prints. Though the switch to the Deardorff took away some spontaneity, it adheres to the same "snapshot" principle of Meyerowitz's earlier Street Photography: that of capturing a moving city in a split moment in time and place. Speaking of the location on the intersection of 59th street and Madison Avenue, Meyerowitz suggested that he had "picked a hard, sunny corner, with something in the frame that appealed to [him];" in this case specifically, a "gaudy and horrible" office building that was "exactly of its era."

In terms of its composition, we see that the picture frame is divided into geometric shapes of light and shadow. Against this architectural order, passing individuals are purposeful, concentrated and introspective, striding across the composition in a mix of drab greys and tans and gaudy pink or blue. Yet collisions seem somehow inevitable given that each figure is in a world of their own. The color film meanwhile is integral to creating the overall impression. As Meyerowitz himself put it in this discerning quote: "When I first showed these sorts of image to my friends Garry Winogrand and Tod Papageorge they thought that I had lost my mind, or lost my eye. And yet, when I look back on this picture - at the newsagent, or the man striding around the corner, or the gigantic woman - I feel a kind of giddy delight that I was there [...] Anyone who looked at this in 2050 would be able to say: 'So that's what it was like to be in New York 75 years ago."

Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Beginnings of Street Photography

In the very beginnings of photography, the world had to "stand still" in front of the bulky copper-plate camera. Advances in its technology meant that exposure times quickly decreased, but the first Daguerreotypes placed restrictions on the choice of subject available to the photographer, especially outside of the studio. The Daguerreotype's limitations were revealed in 1838 by the inventor himself - Louis Daguerre in what is thought to be the very first street photograph. For his iconic image Boulevard du Temple (1838), Daguerre pointed his camera out of his studio window to capture a view of the Parisian boulevard below. The long exposure time meant that the busy Paris thoroughfare appears empty, except for two men - a shoe-shiner and his client - who remained still for long enough that their images (towards the bottom left of the frame) left their impression on the photographic plate.

Two years after this picture was taken, William Henry Fox-Talbot had developed the Calotype, and though it lacked the detail of the copper plate Daguerreotype, it offered capacity for producing a flexible negative from which multiple copies could be made. The Calotype was adopted by the likes of Charles Nègre who took his camera out of the studio onto the streets of Paris. Known for his early experiments with different lenses, Nègre managed to capture something of the movement of the city. Amongst his most successful images were Market Scene at the Port de L'Hotel de Ville, Paris and Chimney Sweeps Walking, both taken in 1851. Other important examples of early street projects followed, such as John Thomson's Street Life in London in 1877 and Paul Martin's London by Gaslight series (c. 1896).

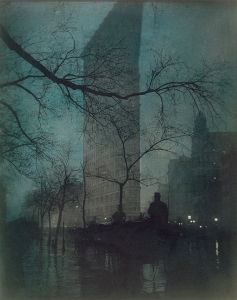

The City

By the turn of the century, the city was seen as an obvious site for new picture possibilities. As photography historian Graham Clarke observed, "photography established itself in a period when the growth of the city and industry had already provoked a formidable literature and art in response to the increasing influence of urban areas, especially such cities as London, Paris and New York." In New York, the likes of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen were turning towards city architecture in the name of a Pictorialist photographic art. Steichen, a founder member of the Photo-Secession group, was for instance interested in the interrelationship between photography and Tonalist painting. Steichen, who produced several images of the Flatiron Building (the tallest building in the world on its completion in 1902), was interested in adapting and manipulating his photographs and he colorized his images of the Flatiron using layers of pigment in a light-sensitive solution.

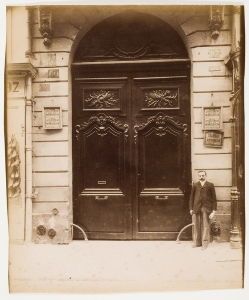

In Paris, meanwhile, Eugène Atget was taking to the deserted city streets and alleyways with the aim of preserving something of the forgotten and unremarkable aspects of the French capital that were being lost to sweeping re-modernization projects. Atget used a large format camera, often with wide views, to capture something of the true ambiance of the city. Though he considered himself a documentarian, Atget's sparse photographs were admired by many important artists working in Paris during the first decades of the twentieth century including Matisse, Picasso, Man Ray, and Man Ray's close colleague, Berenice Abbott.

Abbott was in fact instrumental in bringing the work of Atget posthumously (he died in 1927) to the attention of the American public through her connections with New York's Julien Levy Gallery which acquired most of the Frenchman's negatives and prints on his death. When she arrived in New York (from Paris) Abbott (herself a native American) was taken aback by the transformation in New York's manmade landscape. Abandoning her allegiance to the American and French avant-gardes - which seemed to her like folly given the onset of the Great Depression - Abbott, with the financial support of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (between 1935 to 1939), followed the spirit of Atget in documenting the changing face of the city.

Concepts and Styles

Towards a Snapshot Aesthetic

Photography's first revolution occurred as early as 1888 when George Eastman produced the Kodak camera. The Kodak was a small fixed focus camera that was relatively cheap and easy to use (it was sold on the slogan "you press the button and we do the rest"). By the turn of the century the emergence of the hugely popular pocket size Brownie prompted the Vorticist Alvin Langdon Coburn, to comment that the camera had become as "common as a box of matches." Indeed, historian Graham Clarke suggested that by empowering anyone to "construct an individual view of their world" the Brownie had effectively given rise to the "ultimate democratic art form." The issue for Street Photographers and photojournalists was still one of professional quality however. This discrepancy was soon to be remedied by the German Leica company. Leica developed its first 35mm camera in 1914 and, following modifications to several prototypes, Leica manufactured a practical 35mm film camera from 1924. The Leica was a small camera producing small negatives that lent themselves well to enlargement. Thus, in order to achieve its ends, the Leica offered fast shutter speeds with high quality lenses that would yield high definition negatives.

While the Leica was the camera of choice for many Street Photographers, some, such as Vivian Meyer, turned to a 120mm format twin lens Rollieflex camera. The Rollieflex was held at waist or chest height and allowed for greater depth of field and picture detail. However, the Rolliflex demanded a slower exposure time and the camera was more noticeable to the passer-by meaning the photographer had to forego some of their anonymity. More recently still, photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz even experimented with the larger format 8x10 Hasselblad camera.

The “Decisive Moment” and the “Vernacular”

During the 1930s the famous French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson set the precedent for what became known specifically as Street Photography (though, like most Street Photographers, that term does not do justice to his whole career). Inspired initially by Martin Munkácsi's image Three Boys at Lake Tanganyika (c.1930) - "I suddenly understood that photography can fix eternity in a moment" he said on seeing the Hungarian's photograph - Cartier-Bretton bought a Leica I fitted with a 50mm lens. He painted his camera black, making it less visible to onlookers, and took to the streets of Paris with the aim of "fixing for eternity" something of the movement of the city. Through what became better known as his "decisive moment" technique, Cartier-Bresson's street photography distinguished itself from the more prosaic documentary approach.

A contemporary of Cartier-Bresson was the Hungarian born French photographer Brassaï who was widely acclaimed for his photographs of Parisian night life and especially his famous book Paris by Night (1932). As much as Cartier-Bresson is associated with "the decisive moment" so Brassaï is associated with the idea of slang, or "vernacular," photography. Brassaï developed innovative solutions to help compensate for the lack of daylight, using the street and interior locations as "sets" from which he could draw on indirect, or man-made, lighting sources. Both men formed close bonds with the Surrealists and so their Street Photography - which at core embraced the principle of the Surrealist's spontaneous "automatic" technique - is often attributed with blurring any obvious distinction between what might be called Documentary Photography and fine art. But ultimately, it was the photographers' curiosity for the lived phenomena of twentieth-century urbanization, and of Paris in particular, that determined the subjects onto whom, and on which, these two great pioneers turned their lenses.

Towards The Americans

There was no such room for artistic ambiguity when viewing Walker Evans's raw photography. Evans is still perhaps best known for his social documentary photographs of the Great Depression and his 1938 collection American Photographs was in fact the first photographic exhibition held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That exhibition also featured Street Photography from his travels to Cuba and the Southern states, though his most iconic street photographs were taken between 1939-41 - and in fact beneath the streets - on the New York subway system. Using a concealed 35mm Contax camera, which Evans activated with a rigged shutter cable release, he was able to record the culture and manners of commuters.

An important contemporary of Evans, the Brooklyn born Helen Levitt took her inspiration from both Cartier-Bresson and Evans. Levitt used her camera to capture the street lives of women and children, and people from New York's minority communities through a style that blurred the line between documentary and theatricality. Levitt's work is revered for the way it matched creative and technical skill with a tender humanism. But there can be little doubt that Street Photography was elevated to new artistic standards in the late 1950s with the publication of Robert Frank's book The Americans, undoubtedly one of the most influential photographic projects of the 20th century.

Driven by the wanderlust of a Beatnik, Frank took his Leica onto the streets and highways of 1950s America. Describing himself as being "like a detective or a spy" Frank used his camera to capture an unvarnished and unguarded cross-section of American society, and in so doing, he brought a new sense of liberation to photographic art. Frank shunned the principle of balanced compositions in favor of crooked, grainy high contrasts in black and white and his spontaneous approach to his subjects was to prove decisive in expanding the creative possibilities for Street Photography. The Americans, which boasted an introduction from the famous Beat writer Jack Kerouac, was so influential because Frank achieved a further - or higher - meditative dimension to his work. He realized this feat by coupling images of American citizens with the street signs and symbols of consumer culture that defined their lived environment. The spectator is therefore encouraged to look at The Americans as a whole; to make sense of the collected images through poetic and conceptual relations between his subjects and how they interact with their immediate surroundings.

The New “Golden Age”

In 1967 the New Documents exhibition announced the arrival of Frank's successors. Introducing the work of Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus, the exhibition's curator, John Szarkowski, spoke of a new approach to Street Photography; one that "emphasized the pathos and conflicts of modern life presented without editorializing or sentimentalizing but with a critical, observant eye." The three colleagues represented then a shift that saw the point of view of the photographer add to the meaning of the image. Arbus identified with, and duly sought out, particular subjects, namely those who occupied the margins of society (outsiders whom she affectionately referred to as "freaks"), Winogrand's attitude was often (though not always) one of an aggressive intruder whose aim was to elicit a response from his subjects when confronted with his camera. Friedlander, meanwhile, demonstrated a particular liking for reflections and shadows, usually his own, in windows, glass doors and mirrors while his attraction to signs, billboards and other hoardings saw critical readings of his work align with the postmodern idea of a hyperreal (the idea that all truth is masked by so many signs) America. And though he came to the fore a little later on, Joel Meyerowitz, who was most admired for changing negative attitudes towards color photography, spoke of his Street Photography in erotic terms, suggesting that his own take on New York street life during the mid 1960s and early 1970s was about "The heat of the gazes between people, the charged mystery that arises from capturing chance moments on the fly."

The Ethics of Street Photography

Some countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, where privacy rights do not extend to public places (though what qualifies as a public and private space is often contested), the rights of the photographer are favored. In other, European Union, countries, where the right to freedom of expression is challenged by the individual's right to ownership of his or her image, the situation is even more complex.

This point can be illustrated through Robert Doisneau's 1950 photograph The Kiss. Depicting a young couple stopping to kiss on a busy Parisian street, The Kiss has become an internationally recognized symbol of romantic love. Yet the photograph (unlike most of Doisneau's pictures) was not entirely impromptu. Having seen the couple (Françoise Delbart, and Jacques Carteaud) kissing, and, not wanting to photograph them without their permission, Doisneau asked if they would repeat the kiss for the camera. In fact, the story of the image's creation only came to light because another couple, believing wrongly that it was they who were depicted, sued the photographer for taking the photograph without their knowledge. They were able to bring the law suit because French law states that the individual owns the rights to his or her own likeness. Even putting the legal implications to one side, the Street Photographer carries with them the perennial moral dilemma of exploiting the lives of strangers for their own artistic ends.

Later Developments - After Street Photography

In the 1970s Street Photography fell out of favor in terms of media attention and gallery support. Though noted Street Photographers, like Martin Parr, Tom Wood, Alex Webb and Boris Savelev emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, others struggled to make a name for themselves. However, by the turn of the century the development of new digital technology and social media exhibition platforms created new possibilities for Street Photographers including the likes of Paul Graham, Laurisa Galvan, Carolyn Drake, Mark Alor Powell, and Matt Stuart. Platforms like Instagram and Flickr, and the website In-Public have made it possible for Street Photographers to form online collectives and to exhibit their work across international borders. Flickr, for instance, has over 400 groups with half a million members dedicated to Street Photography.

However, some observers, such as the Canadian photographer and writer Michael Ernest Sweet, have started to query contemporary Street Photography's validity as art. He speaks for instance of the rise of "machinegun photography," a technique whereby the digital camera (or phone) is used in "burst mode," or, the related technique through which a photographer (such as Mark Cohen) adopts a "no finder" (no viewfinder and no framing) style of shooting. Such approaches leave everything to chance and do not, in Sweet's view, bear serious comparison with the likes of Cartier-Bresson, Evans, Frank, Meyerowitz, or Arbus. It was not only the technique that troubled Sweet. There was a question of editing too. As he said: "Someone once claimed that a great photographer makes about a hundred good images in a lifetime, maybe a dozen truly great photographs." Sweet suggested that this "seems congruent with the history of photography, but plainly incongruent with the current Street Photography community where it is common for a photographer to upload a dozen or even two dozen images a day! This is simply not sustainable, not as art anyway."

Useful Resources on Street Photography

- Street PhotographyOur PickBy Sophie Howarth and Stephen / 46 contemporary street photographers

- Bystander: A History of StreetBy Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz

- The Photograph (Oxford History of Art)By Graham Clarke

- Lee Friedlander: The American MonumentBy Lee Friedlander

- Lisette ModelBy Lisette Model with a preface by Berenice Abbott