Summary of Documentary Photography

The term Documentary Photography describes photography that attempts to capture real-life situations and settings. Since Nicéphore Niépce made the first photograph in 1816, photography's capacity to capture reality led to enthusiastic interest in documenting all aspects of contemporary life. As a result, Documentary Photography became a genre as early as the mid-1800s. As the medium developed, however, Documentary Photography became so diffuse it came to be discussed through a whole series of photographic sub-genres.

Lacking, then, a truly precise definition, Documentary Photography is best thought of as an umbrella term that encompasses many styles and themes including: Social Documentary; Conservation Photography; Ethnographic Photography; War Photography; the photo essay; New Documents; and Social Landscape photography. What unites these styles at basis is the principle that the camera is in essence a machine for recording reality. Though one cannot say it is objective, the intention of the documentary photographer is to bring to light some otherwise hidden reality or injustice. Stylistically, documentarians typically favor sharply focused and/or pure images, that eschew darkroom manipulation or forgery. Other genres of photography, including Street Photography and Photojournalism, sometimes include particular works that are considered documentary images, though both genres primarily focus on capturing a moment, or split second whether that be an encounter on a street or a moment of breaking news.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- More than any other medium, the camera "machine" lends itself best to documentary because the spectator is predisposed to believe the visual evidence put before them. Documentary Photography can be thus presented on its own or as part of a bigger written or spoken project (as evidenced, say, in the photo essay).

- Given its commitment to revealing a particular truth, Documentary Photography resists the idea of image or subject manipulation. This is in fact a rule-of-thumb rather than a hard-and-fast tenet. It remains true, however, that, in principle, Documentary Photography offers a clear divergence from art photography because the latter tends to alter or embellish reality.

- Documentary Photography will often aim at exposing social and/or humanitarian injustices. In this respect it shares close links with War and Street Photography but these rely more on a "snapshot" aesthetic whereas Documentary Photography tends to be more planned in its narrative structure and pictorial composition.

- In addition to its focus on the human figure, Documentary Photography includes a trend within the genre that simply "documents". Though the likes of Conservation Photography and Ethnographic Photography can be taken up for artistic and/or political purposes, the primary intention of the photographer is to do no more than "document" a disappearing or unknown world.

Overview of Documentary Photography

One of the earliest Documentary Photographers, Danish immigrant Jacob Riis, was so successful at his art that he befriended President Theodore Roosevelt and managed to change the law and create societal improvement for some the poorest in America.

Important Photographs and Artists of Documentary Photography

Bandits' Roost, 59 1/2 Mulberry Street

This photograph depicts an alley in a slum located in what was called "The Bend," a notorious neighborhood between Mulberry, Baxter, Bayard, and Park Streets in New York. Riis said of The Bend that "Abuse is the normal condition...murder its everyday crop."

Here, two men on the right seem to guard the entrance to "the Bend" while the man leaning on the club only heightens the sense of menace. Behind them, another man casually perches on a staircase railing (possibly the gang leader) while three other figures cluster on the opposite staircase. All the men are turned to face down the camera. Adding to the general mood of urban despondency, a woman and a child lean out of windows in the building on the right, while in background, clothing hangs on lines strung along the alley. Overall, a sense of crowded poverty and desperate circumstances becomes the backdrop for Riis's foreboding portrait of the Mulberry Street "bandits".

Raised in Denmark, Riis arrived in New York in 1870. By 1877 he had begun working as a police reporter for The New York Tribune. A year later, after reading about the invention of magnesium flash powder, which made night photography possible, Riis took up photography. He began visiting the slums at night, where, accompanied by his two assistants and a policeman, he sometimes startled the residents with the abrupt flash of his camera. As Bonnie Yochelson wrote, his images "captured what had never been seen before in a photograph [while they] retain their power today because the harsh light and haphazard compositions convey the chaos of living in poverty."

Influenced by the progressive social reform movements that had initially emerged in the mid-1800s with Felix Adler's founding of the Society for Ethical Culture, Riis published his photographs, along with accompanying text, in How the Other Half Lives (1890). The groundbreaking work, documenting the poverty of urban immigrants, spurred legislative reform and became thus a seminal work of Social Documentary photography. Yet, while his images captured the reality of slum life, Riis also perpetuated many of the stereotypical views of the era. As contemporary curator Daniel Czitrom wrote, "I've always been struck by the tension between the empathy and sympathy that's powerfully depicted in many of those images, and the kind of stereotypes, racial language, that he uses in the text. There's a tension between the text and the photographs. Today, no one really reads Riis anymore, and yet the photographs remain incredibly moving."

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Addie Card, 12 years. Spinner in North Pormal Cotton Mill

Dressed in her uniform of a dirty work smock, and her bare feet blackened with grease, Addie Card leans with one arm casually resting on the spinning machinery that fills up the background with spindles and skeins. Her blank face stares at the viewer, evoking the grueling toll of child labor. Writer Elizabeth Winthrop observed of Addie that her "left arm rests easily on the huge machinery but crooked at a strange angle, as if perhaps a bone had been broken and never set properly," perhaps incurred while working, as terrible industrial accidents were frequent. Winthrop added that "To keep her hair from the frame's hungry grasp, it is pulled tight and pinned in a style befitting a grown woman." Yet her delicate features, her sad eyes, and her right arm hanging in exhaustion at her side, give her the wistfulness of a child. Hine was to describe her in his notes, as an "Anaemic little spinner" who first claimed to be ten years old, then admitted that she was twelve and had started working during the summer but intended to stay on. Her deception about her age reflected the reality that manufacturers believed that younger girls, due to their small hands and gender, were ideal textile workers.

Hine had studied sociology before moving to New York in 1901 where he taught at the Ethical Culture School, introducing photography as a lessons aid. Resigning his teaching position in 1908, Hine began photographing child laborers, often under cover, in textile mills, coalmines, and factories for the National Child Labor Committee. As art historian Lisa Hostetler wrote, "not only have [his images] been credited as important in the passing of child labor laws, but [they] also have been praised for their sympathetic depiction of individuals in abject working conditions." Hostetler added that Hine had "labeled his pictures 'photo-interpretations,' emphasizing his subjective involvement with his subjects [developing an approach that] became the model for many later documentary photographers, such as Sid Grossman and Ben Shahn."

Gelatin silver print - Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection

Three Farmers

Sander's photograph depicts three young farmers, dressed up as city dandies in suits with hats and canes, on their way to a Saturday night dance in the Westerwald region of Germany (where Sander was born). An incongruous effect is created by the contrast between their fashionable appearance and the setting with its muddy path and vast fields in the background. Looking for new clients, Sander returned to the region in 1910 after establishing his studio in Cologne. One evening, by chance, he encountered the three men moving along the road and asked them to pose for the lengthy exposure required by his large format camera. The two men on the right echo each other's still pose, while, the man on the left, caught in midstride, his cane at an angle, and a cigarette in his mouth, seems to have just paused for a moment to turn to look at the viewer. As a result Sander's most famous image takes on qualities of both a formal photo and a snapshot, while at the same time as cultural historian Michael Jennings wrote it documents the "momentum of the transition away from the land and into the cities."

Like much of Sander's work, the image, juxtaposing the young men's posing as urban dandies with the marshy and vacant fields, conveys a sense of the dissonant in ordinary life, a quality that later influenced the photographer Diane Arbus. The frontal shot, suggesting the three have been stopped by the camera's gaze, is also informed by a modernist awareness of the role that the observer/photographer plays in creating the image. As the historian Wieland Schmied wrote, Sander "sought to combine constructivism and objectivity, geometry and object, the general and the particular, avant-garde conviction and political engagement, and which perhaps approximated most to the forward looking of New Objectivity."

Considered the greatest German portrait photographer of the early 20th century, Sander spent most of his life working on his People of the Twentieth Century, a documentary project to produce the representational types of Weimar Germany. Striving to create "a physiognomic image of an age," cataloguing "all the characteristics of the universally human," and depicting the seven categories, which he based upon class and occupation, Sander meant to document a nation. Though the project was not completed, due to Nazi suppression of his work, he published Face of Our Time (1929), a collection of sixty portraits including Three Farmers. His portraits influenced photographers including Walker Evans and Irving Penn, and this picture directly inspired Richard Powers's debut novel, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance (1985), and the art critic John Berger's "The Suit and the Photograph" (1980), a highly influential essay upon art theory and criticism.

Gelatin silver print - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Une vitrine Avenue des Gobelins à Paris

Atget's image depicts a storefront window where fashionably dressed male manikins stand amid displays of men's trousers and reflections of the vacant Paris street, with its tall buildings and leafy trees. The forms and their reflections comingle, creating a play upon the perception of reality, as the manikins seem to stand within the clothing display while they also seem to emerge from the city street, much like window-shoppers looking in.

Atget's work - championed in the 1920s by the likes of Man Ray, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and André Derain - became particularly influential on the Surrealists. Man Ray felt Atget's photographs of shop windows were intuitively surrealist and began collecting his photographs, using During the Eclipse (1912), a photograph of a crowd gathered to view an eclipse, for the cover of the Surrealist's magazine, La Révolution Surréaliste. A humble man who viewed himself very much as a documentarian (rather than an artist), Atget, granted permission for the use of his photograph with the stipulation: "Don't put my name on it."

On discovering Atget's photographs for herself, Man Ray's assistant, Berenice Abbot, soon to become a renowned photographer in her own right, became a lifelong champion of his work, promoting its publication in America and preserving his archives. In 1968 she sold his collection to the Museum of Modern Art declaring that Atget "will be remembered as an urbanist historian, a genuine romanticist, a lover of Paris, a Balzac of the camera, from whose work we can weave a large tapestry of French civilization." Photographers from Ansel Adams to Walker Evans and Lee Friedlander cited Atget as a signature influence.

Albumen silver print from glass negative - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

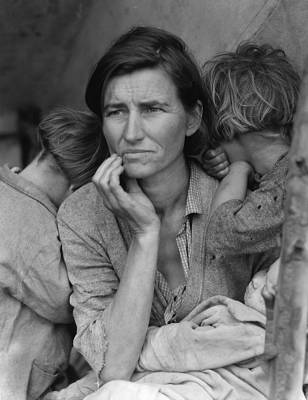

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

This image, one of the most iconic of all documentary photographs, shows a woman in a migrant pea-pickers camp. Their faces turned away from the camera, her two young children cling to her, as she holds an infant, swaddled in a worn blanket, and looks somberly, her face lined with worry, into the distance. The photograph was originally captioned "Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California" and was one of several images that Lange took of Florence Owens Thompson and her family in their makeshift camp.

The Dust Bowl farming disaster in particular had had devastating effects upon all aspects of American life with the poorer classes facing the direst situations and the FSA's documentary project supported the social reform programs of the Roosevelt administration. Lange's photographs appeared in a 1936 issue of the San Francisco News, following a story highlighting the near starvation conditions in the camp, and contributed to the success of the relief effort. Stryker felt Lange's image symbolized the entire project, as he said, Migrant Mother "has all the suffering of mankind in her but all of the perseverance too. A restraint and a strange courage. You can see anything you want to in her. She is immortal."

Referring to the photograph's historical significance, art historian John Szarkowski said "one could do very interesting research about all of the ways that the Migrant Mother has been used; all of the ways that it has been doctored, painted over, made to look Spanish and Russian; and all the things it has been used to prove." Reproduced in textbooks, postage stamps, political campaigns, and museum displays, the image has become not only a symbol of the Great Depression, but, as historian Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites wrote, "a template for images of want [and a] powerful statements on behalf of democracy's promise of social and economic justice."

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

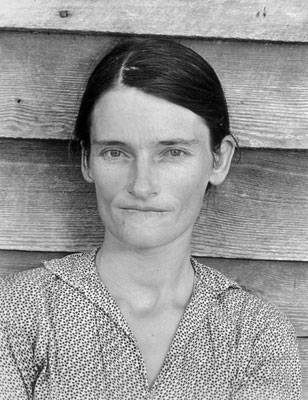

Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife (Allie Mae Burroughs)

Evans's iconic photograph depicts Allie Mae Burroughs, the wife of an Alabama cotton sharecropper and mother of four. She is standing just in front of the family's cabin wall, facing the viewer directly, engaging our look. Only twenty-seven years old, but worn down by work and worry, her expression conveys the hard circumstances of her life. The formal composition, framed by the horizontal lines of the wood siding, emphasize the lines of her eyebrows and mouth, and create the effect of a distinctive, but inscrutable, personality, highlighted against a harsh, flat environment. As writer Lincoln Kirstein, wrote: "The power of Evans's work lies in the fact that he so details the effect of circumstances on familiar specimens that the single face, the single house, the single street, strikes with the strength of overwhelming numbers, the terrible cumulative force of thousands of faces, houses, and streets."

Evans was initially drawn to literature, spending 1927 in Paris writing essays and short stories. He turned to photography upon his return to New York in 1928 when he synthesized his interest in irony, narrative, and poetic lyricism with his images. In 1935 he agreed to photograph a community of West Virginia coalminers for the U.S. Department of the Interior and that same year began to work for Fortune magazine. Close friends with the writer James Agee, the two went to Alabama for a feature on sharecroppers in 1936, and lived on and off with three families in Hale County, including the Burroughs. Sharecroppers leased their land, home, farm implements, and livestock and had to give half of their crop to the landlord. As a result of this arrangement, families like the Burroughs often ended the year in debt. During their time with the Burroughs, Evans took four photographs of Allie Mae standing in front of the cabin, each image capturing a distinctive expression.

While Fortune rejected the feature, it was later published as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a 500-page volume with Allie Mae featured on its cover. Though the photograph became a classic of both the Depression era and of Documentary Photography per se, and creating a great social statement at the same time, Evans said of the project, "This is pure record not propaganda . . . No politics whatever." Evans was dubbed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as the "progenitor of the documentary tradition" and his images influenced a new generation of photographers including Robert Frank, Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, and Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Gelatin Silver Print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Spinner

In this image that seems to come from an earlier era, a woman, dressed in dark clothing, holds a spindle in one hand and a skein of thread in another, while behind her another woman is attending to her sewing. Kneeling on the floor, arms outstretched with the spindle held up to one side of her face, as she catches the thread between her teeth - the woman has almost the grace of a dancer, her face, composed, concentrated on her art.

Photographed in Spain in 1950, Smith took this image of María Ruiz Rodríguez in Deleitosa, a village of 2,650 people in Extremadura. The residents of the village lived a traditional life, lacking modern conveniences such as indoor plumbing, drainage systems, or telephones. The image was published with 17 other photographs, as Spanish Village, a photo-essay that appeared in Life magazine. It is considered a masterwork of humanist photography, which emphasized the universality of human life and feeling and depicted the aesthetic beauty of ordinary events. Smith said his purpose was "to capture the action of life, the life of the world, its humor, its tragedies, in other words, life as it is. A true picture, unposed and real."

During World War II, Smith worked as a war correspondent, covering 13 invasions in Europe and the Pacific, as well as combat missions. In 1945, he was badly injured by a grenade during the Okinawa invasion and returned home for two years of surgery and recovery. Smith described "The day I again tried for the first time to make a photograph, I could barely load the roll of film into the camera. Yet I was determined that the first photograph would be a contrast to the war photographs and that it would speak an affirmation of life." That first photograph was his Walk to Paradise Garden (1946), showing his two young children emerging from a dark and heavily wooded area, and Smith continued with his "affirmation of life" worldview in subsequent photo-essays.

Gelatin silver print - Museo Centro Nacional de Arte: Reina Sophia, Madrid

Trolley - New Orleans

Frank's photograph depicts a trolley passing by on the streets of New Orleans, as the passengers look out through the bus window. The image conveys a distinct sense of each distinct personality but also a sense of segregation and social power. The contrast between the black reflective sides of the trolley and the white vertical bars dividing the seating sections echoes visually the sense of a society divided by race.

In 1955, while taking photographs of a street parade, Frank saw the trolley passing by and pivoted, just in time, to take this shot before the trolley vanished from view. This image was used as the cover image for early editions of The Americans (1958), where some critics cited it as evidence of Frank's "anti-Americanism." Simultaneously, his pioneering snapshot technique was also attacked, as the UK monthly Practical Photography cited its, "meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness."

The book, as art critic Sean O'Hagen wrote, "challenged all the formal rules laid down by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans, whose work Frank admired but saw no reason to emulate. More provocatively, his images flew in the face of the wholesome pictorialism and heartfelt Photojournalism of American magazines like Life and Time. The Americans was shocking - and enduringly influential - because it simply showed things as they were. 'I was tired of romanticism,' Frank told me, 'I wanted to present what I saw, pure and simple.'"

Growing up in Zurich, Frank moved to New York in 1947 where he worked at Harper's Bazaar under art director Alexey Brodovitch. Uneasy with the constraints of fashion photography, he traveled to South America where he took photographs in remote villages and lived hand to mouth. Returning to New York in 1950, he met Edward Steichen who included some of his images of Peru in 52 American Photographers, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Following the exhibition, Walker Evans became a mentor and supporter of Frank's work. In 1955 a Guggenheim Fellowship allowed Frank to undertake a series of American road trips. While he took around 28,000 images, only 83 black and white photographs were included in The Americans, which was published in France in 1958 before appearing in America the following year. As O'Hagen noted, "it changed the nature of photography, what it could say and how it could say it," and "remains perhaps the most influential photography book of the 20th century." Frank influenced Jeff Wall, Ed Ruscha, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and many other subsequent photographers.

Gelatin silver print - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

Nashville

This photograph focuses on a corner of a motel room, its dark emptiness illuminated by a television screen which displays an extreme close-up of a woman's smiling face. Cropped at her eyebrows and lower lip, her animated expression fills the entire screen. Behind the television a man's shirt, implying the photographer's presence, hangs on the upper corner of a closet or bathroom door.

The photograph was part of Friedlander's Little Screens, a series where the portable television, a new phenomenon at the time, featured prominently in his images of sterile and lonely motel environments. Walker Evans introduced these shots, which appeared as a photo-essay in a 1963 issue of Harper's Bazaar, as "deft, witty, spanking little poems of hate." Friedlander adopted a snapshot approach that artist Martha Rosler described as conveying "casualness" and "ordinariness," while at the same time bringing together "disparate elements and image fragments." Friedlander did not posit his work within a political or cultural context but said, "I think private moments make the interesting picture." Friedlander became a leading figure in New Documents photography that emerged in the late 1960s. As art historian Lisa Hostetler suggested his work possessed "a constant awareness of the photographer's relationship to the picture plane and places at least as much importance on it as on the image's ostensible subject."

Gelatin silver print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Mujer Ángel (Angel Woman), Sonora Desert

This image depicts an indigenous woman of the Seri people. She is wearing a long white billowing skirt, her long hair trailing down her back as she emerges from a rocky hillside, the vast desert of Northern Mexico extending before her. In her right hand she carries a boom box and her left hand holds what appears to be a makeshift cane or a staff. The rocky hillside cuts a diagonal across the photograph from the upper right to the lower left, dividing the image into two triangles so that the woman's figure dominates the view. As a result she seems somehow mythical and archetypal. Because the shot is taken from below, it is as if we were following her, as she strides forward energetically, powerful with mysterious purpose.

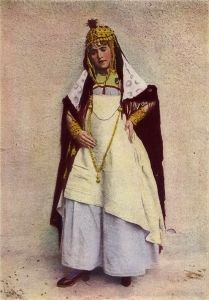

In 1978 the Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico commissioned Iturbide to work on a series about the Seri people who live along the Arizona/Mexico border in the Sonoran desert. At the time that she took this photograph she was living in Punta Chueca, a community of 500 people. Iturbide described how, "On the day of this particular image, I went with a group to a cave where there are indigenous paintings. I took just one picture of this woman during the walk there. I call her Mujer Ángel [Angel Woman], because she looks as if she could fly off into the desert. She was carrying a tape recorder, which the Seris got from the Americans, in exchange for handicrafts such as baskets and carvings, so they could listen to Mexican music." Accordingly Iturbide has described this photo as representing "the transition between their traditional way of life, and the way capitalism has changed it."

The 2008 Hasselblad Award cited Iturbide as "one of the most important and influential Latin American photographers of the past four decades," as she "extended the concept of documentary photography, to explore the relationships between man and nature, the individual and the cultural, the real and the psychological." Beginning in the 1970s she has worked primarily on ethnographic series that focus on a particular culture, saying, "I seek to trap life in the reality that surrounds me, remembering that my dreams, my symbols, and my imagination are part of that life."

After the death of her six-year-old daughter in 1970, Iturbide turned to photography and studied with Manuel Álvarez Bravo who became her mentor. Using a Straight Photographic approach to combine Social Realism and Surrealism, his style influenced her, but she has primarily credited his example, saying, "Álvarez Bravo taught me another way to live." She has said of this image, "It's my favorite photograph, because I don't remember taking it. Maybe it was some kind of spirit out there that took it." Her work has received great contemporary interest, as shown by her 2018 retrospective Graciela Iturbide's Mexico at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and a book length monograph.

Gelatin silver print - The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC

This portrait depicts, Scott Andrew as Misty, a well-known drag queen who performed as Miss Demeanor, and Jimmy Paulette, best known later as a hairstylist for Vogue. The pair are framed by the taxi's rear and side window against the backdrop of New York. The camera's flash creates a kind of spotlight effect as it highlights their blue and gold wigs, Misty's tight black pvc top, Paulette's gold bra and the contrast of their dark eyes and red lips against their pale skin. Open to interpretation, the photograph has been seen by some critics as depicting the two on their way home after an "all-nighter" while others have seen them as working performers, in a quiet moment, on their way to a performance. However, as Paulette later explained, the "photo of Scott and I in the back of the cab is us on the way to the [Pride] parade, about 12:00 noon." For her part, Goldin said of the image that "I wanted to pay homage, to show them how beautiful they were. I never saw them as men dressing up as women, but as something entirely different - a third gender that made more sense than either of the other two. I accepted them as they saw themselves; I had no desire to unmask them with my camera." As a result, the portrait conveys a sense of distinctive personality, confident, even defiant with self-definition.

With Mark Morrisroe and David Armstrong, Goldin was part of the so-called "Boston School". The school promoted a snapshot aesthetic, creating grainy and poorly lit portraits in an attempt to convey a sense of intimate authenticity. Goldin was influenced by Brassaï 's images of Paris' hidden night life, and by contemporary underground films like Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures (1961) which celebrated the New York camp scene. In the 1970s she began taking photographs of her gay friends - quite often glamorously dressed up as constructed identities - in the home, and at the Other Side, a gay bar in Boston. Her first book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1981) documented heterosexual relationships, though she continued to socialize with, and photograph, the gay community. "I met a whole new crowd of queens in N.Y. in 1990 ... My old obsession was reawakened," she said, "I developed one fixation after another. I photographed my new friends constantly ... After years of experiencing and photographing the struggle of the two genders with their codes and definitions and their difficulties in relating to each other, it was liberating to meet people who had crossed these gender boundaries."

This image was included in her book, The Other Side (1993) named for her hometown bar, which included color photographs of drag queens in New York, Berlin and Paris, Goldin said of the book "the pictures [...] are not of people suffering gender dysphoria but rather expressing gender euphoria."

Photograph, colour, Cibachrome print, on paper mounted onto board - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Iceberg Between Paulet Island and the South Shetland Islands in the Antarctic Peninsula

Salgado's photograph depicts an iceberg, its jagged form, floating on a dark sea beneath a sky of luminous and foreboding clouds. A little off center, a large opening in the iceberg evokes an arched entrance or a keyhole, while on the upper right, the ice takes on a perpendicular shape, creating thus a sense of the form as carved perhaps by powerful architectural forces. The light becomes a material presence, as art critic Laura Cummings wrote, "Salgado's habitual monochrome runs all the way from coal black to silver and burning white, with a thousand tones of grey in between. The lighting is characteristically spectacular, with plenty of backlighting and operatic contrasts." Commenting on Salgado's aesthetic preferences, Cummings notes that "Nothing can have absolute or accidental priority in monochrome, nothing can leap out simply by virtue of its colour. Black and white puts everything on equal footing, on the same planet."

Raised in Brazil, Salgado initially worked as an economist before taking up photography in 1973. For two decades, working with Magnum and other agencies, he traveled the world, photographing images such as workers subjected to brutal conditions, the effects of global migration, and the wars in Bosnia and Rwanda. In 1999, he had a psychological and artistic crisis. As he described it, "I had seen so much brutality. I didn't trust anymore in anything. I didn't trust in the survival of our species."

He inherited his father's Brazilian ranch during the same period, and with his wife, Lélia, turned to restoring what Salgado called "a dead land." Art critic Richard Lacavo wrote, it became, "a kind of dual restoration project - for himself and his Brazilian paradise lost [...] As his personal world regenerated, Salgado got an idea: For his next project, why not travel to unspoiled locales - places that double as environmental memory banks, holding recollections of earth's primordial glories?"

Salgado included 200 photographs in Genesis, a photographic exhibition that toured worldwide, and a book (of the same name) published in 2013, both of which were met with critical and public acclaim. In 2014 filmmaker Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, the photographer's son, filmed The Salt of the Earth, a documentary focused on Salgado's life and work.

Gelatin silver print - Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York

Beginnings of Documentary Photography

Early Documentary Projects

![David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson's <i>Willie Liston, 'Redding [cleaning or preparing] the line'; Newhaven fisherman</i> (1845) shows one of many fishermen portrayed in their extensive documentation of village life.](/images20/photo/photo_documentary_photography_1.jpg?1)

The partnership of David Octavius Hill with Robert Adamson, founder members of what is thought to be the first photographic studio in 1843, produced one of the earliest documentary projects to gain recognition. For the next four years (until Adamson's unexpected death in 1848) the two produced some 3,000 images documenting ordinary life in Scottish fishing villages, as well as landscapes and urban scenes from the adjoining region.

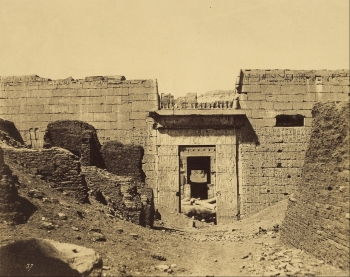

Other notable documentary projects in the 1850s included the early Egyptologist John Beasley Green's photographs of ancient ruins in Nubia, and Philip Delamotte's series of photographs of Joseph Paxton's innovative Crystal Palace being disassembled (and then reassembled in Sydenham, Southeast London) following London's Great Exhibition of 1851. In 1854, supported by Prince Albert, and the British Secretary of State for War, Roger Fenton undertook an early documentary project, as he became the first official war photographer of the Crimean War.

In America, meanwhile, the first well-known documentary project began in 1861 when Matthew Brady, a respected portraitist with a major studio in New York, took a team of photographers, including Timothy O'Sullivan, Alexander Gardner, and George N. Barnard, to the battle fields of the Civil War. After the end of the Civil War (in 1865) Sullivan, and other photographers including William Henry Jackson, began working for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, creating the first comprehensive Conservation Documentary of the American West.

Jacob Riis

Also in America, the police reporter and journalist Jacob Riis turned to photography having read an 1887 report on the German Adolf Miethe and Johnannes Gaedicke's magnesium flash powder invention. The flash device made night-time photography possible while at the same time advancements in printing technology allowed for his images of slum life among the immigrant working classes to be published in newspapers and magazines. His two books, How the Other Half Lives (1890) and The Children of the Slums (1892), garnered wide public interest and critical acclaim and even initiated new social reform programs. Riis duly emerged as a pioneer of American Social Documentary photography and he embarked on a countrywide tour where his lectures, featuring lanternslide displays, helped create an expanding audience for the new photographic genre.

Eugène Atget

The Frenchman Eugène Atget had worked as an actor before turning his attentions to photography in the 1880s. Initially, he created images of objects, monuments, flowers, and landscapes which he called "documents". These he offered to artists as pictorial originals from which they could produce their own works. Atget changed direction in 1900 when a modernization campaign was launched in Paris. Called Haussmannization, after Baron Georges-Eugène Haussman who oversaw the project, the remodernization initiative saw the medieval streets and buildings of vieux Paris (old Paris) demolished and reshaped as public parks and wide city avenues. Documenting old Paris became Atget's life mission with his business card describing him as "Creator and Purveyor of a Collection of Photographic Views of Old Paris." Through thousands of images, he documented buildings, shops, fittings on doors and other decorative elements of the disappearing city.

Atget's mission was not to produce a social commentary but to use his camera rather to document what would be an otherwise forgotten Paris. He achieved the status of artist in the 1920s, however, when his work was championed by the prominent Surrealist photographer Man Ray. The American Berenice Abbott, who was working as Man Ray's darkroom assistant, was herself inspired by Atget's images. On returning to New York, she became a leading documentary photographer in her own right, while continuing to collect and promote Atget's work calling him an "urbanist historian [and] a Balzac of the camera." Atget's work, which elevated "pure" documentary to the realm of fine art in its formal and tonal qualities, influenced Walker Evans and other noted modern photographers.

Concepts and Trends

Social Documentary

Given that both trends developed almost simultaneously, the boundaries between "pure" Documentary (as evidenced, say, by Atget) and Social Documentary (as evidenced, say, by Jacob Riis) have often overlapped. The early work of Lewis Hines falls, however, comfortably within the realms of Social Documentary. In 1908, the National Child Labor Committee hired Hine to photograph child laborers in a variety of industrial locations throughout the United States. Hine's images played a major role in the 1916 Keating-Owen Act, one of the first laws to reform child labor. Later, his projects for the American Red Cross's relief efforts in Europe during and after World War I, and his 1930 documentation of the construction of the Empire State Building, expanded the range of photographic subjects considered of societal importance.

The severe impact of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl crisis of the 1930s led to the development of new relief programs, including roles for artists and photographers in the worst-affected communities. Roy Stryker, head of the Resettlement Administration (later, the Farm Security Administration (FSA)) hired leading photographers including Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and Walker Evans to introduce, as he said, "America to Americans." The project resulted in over a quarter-of-a-million images that have gone down in history as a forceful record of ordinary (and otherwise anonymous) Americans marooned by rural poverty. Following the FSA initiative, Social Documentary became so established it developed its own sub-genres, such as the "Madonna and Child" trope, which showed an impoverished mother doing her best for her children. As art historian Wendy Kozol wrote, this trope became part of the "iconography of liberal reform."

As it evolved, Documentary Photography played a notable role in the development of national and historical archives. Institutions, including the Smithsonian Institution in America and the Société Française de photographie in France, subsequently housed and exhibited images depicting historical events, national crises and geological and geographic records.

Conservation Photography

Conservation Photography uses a documentary approach in photographing nature and landscapes, usually with the goal of advocating the work of preservation and conservation in the natural environment. It originated in the 1860s when, following the Civil War, the US government-sponsored geological surveys that used photographic documentation of the remote landscapes of the west. In 1864 Carleton Watkin's photographs of Yosemite, undertaken for the California State Geological Survey, played a primary role in establishing Yosemite National Park in the national consciousness. Similarly, Timothy O'Sullivan's photographs for the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel played a leading role in establishing the importance of the natural landscape and wildlife and habitat conservation. In 1867 Eadweard Muybridge gained renown for his photographs of Yosemite and, later, the barren territories of Alaska and (later still) the lighthouses along the West Coast.

The conservation mission was complemented by the painterly arts with the English-born painter and illustrator Thomas Moran using his dramatic images (inspired by J.M.W. Turner) of canyons, hot springs, and geysers to help promote Yellowstone National Park in the public's consciousness. In 1871 he had been invited to join F. V. Hayden's geological expedition to Yellowstone where he worked closely with the photographer William H. Jackson. This was followed in 1873 when he joined John Wesley Powell's expedition to the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, and in 1874 when, with Hayden once more, he visited the newly discovered Mount of the Holy Cross in Colorado.

The 20th century brought a renewed interest in conserving the environment, particularly during Theodore Roosevelt's administration as he established 150 National Forests and 18 U.S. National Monuments. Ansel Adams' images of Yosemite and other natural environments made him not only a leading modern photographer but also the leading influence upon Conservation Photography and the wilderness movement. In the 21st century, Conservation Photography has reflected global ecological and environment concerns, as seen in Sebastião Salgado's Genesis (2004-12) collection. In 2005 Cristina Mittermeier founded the International League of Conservation Photographers at the World Wilderness Congress, establishing both the term Conservation Photography and its parameters as a photographic discipline.

Photo-Essay

During the 1930s, leading large format magazines such as Life (founded 1936) and Look (founded 1937) promoted the so-called photo-essays. Even those magazines whose interest in photography had been purely perfunctory began including photo-essays. The photo-essay offered an in depth photographic narrative that typically focused on societal issues. Walker Evan's photo-essays were regularly published in Fortune between 1934 and 1965, and in 1945 he became photographic editor for the magazine, taking on the additional tasks of design layout and copy editing. A potent combination of photograph and written story, Evans's photo-essays became exemplars of a genre that would remain popular with the public well into the 1950s.

However, following World War II, many documentary photographers, including Robert Frank, William Klein, Diane Arbus, W. Eugene Smith, and Mary Ellen Mark, began to rebel against the limitations of photo-essays and the format of illustrated magazines. Following a dispute about the publication of his photographs, Smith left Life and turned to documentary with his images of Minamata in the later 1960s which depicted the residents of the Japanese fishing village who had been severely effected by mercury poisoning. By the 1970s, and largely due to the rise of television as a documentary media, a number of leading magazines had ceased publication, and documentary photographers turned to book publication or gallery exhibitions. Indeed, by the end of the decade art galleries routinely exhibited Documentary Photography, which was typically presented in the photo-essay format, alongside fine art.

New Documents

Seen as a revitalization and new interpretation of Documentary Photography, "New Documents" (less well known as "Social Landscape") photography appeared in 1966 with the George Eastman House's exhibition "Toward a Social Landscape". The genre was properly announced by New York Museum of Modern Art's "New Documents" exhibition of 1967 (hence the name). John Szarkowski, curator of "New Documents," said of the photographers - Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Danny Lyon, and Bruce Davidson - that their "aim has been not to reform life," as was the goal of Social Documentary, "but to know it." Szarkowski argued that the group's "work betrays sympathy - almost affection - for the imperfections and the frailties of society" and that the photographers on display approached "the real world, in spite of its terrors, as the source of all wonder and fascination and value." The "New Documents" approach welcomed mundane subject matter while abandoning Social Documentary's "objective" stance in favor of a self-conscious awareness of the photographer's presence, resulting in often alienated, disconcerting, or unsettling images.

The individual photographers drew upon various influences: Robert Frank and Walker Evans influenced Friedlander, Winogrand was trained in Alexey Brodovitch's Design Workshops (where the motto was "astonish me"), and Arbus studied with Lisette Model. While the works were published in magazines, a notable trend amongst the "New Documents" group was the photographic book that focused on a series of related images, as seen, for instance, in Friedlander's Work from the Same House (with Jim Dine) (1969) and Self-Portrait (1970). Other photographers associated with the group extended the "New Documents" approach to other subjects. Robert Adams's photographs depicted the outdoor landscape and the topography of the suburbs, while William Eggleston's debut exhibition in 1976 led to him being acclaimed as a pioneer of color documentary photography. Associated primarily, however, with the famous sixties exhibition, "New Documents" has been assimilated into Street Photography, and while there remains a strong lineage to Documentary Photography, the boundary lines become blurred given that Street Photography tends to favor spontaneity over planning in its pursuit of the artistic "moment".

Ethnographic Photography

Developing from the earliest days of Documentary Photography, and especially John Beasley Green's photographs of ancient ruins in Nubia in the 1850s, Ethnographic Photography takes its name from the anthropological term "ethnography," the scientific research of specific cultures. In the 19th century, photographers would often travel to remote parts of the world to bring back (or send back in the form of a post card) images of other cultures and peoples for the European public. This popular practice created a kind of photographic tourism. Green's approach was however informed by his work as an Egyptologist, and his images of the ruins and the people of Nubia were valued as scientific records.

Founded in 1888 in Washington D. C., The National Geographic Society launched its National Geographic Magazine. Originally a scholarly journal created for its 165 charter members, in 1905 it expanded its photographic content with the intention of attracting a wider public audience. The magazine's photography focused on particular regions, cultures, tribal peoples, and civilizations and played an important role in establishing Ethnographic Documentary as a genre in its own right. The trend was further influenced by the Farm Security Administration's (FSA) photographs documenting rural poverty that affected entire communities and extended over generations, and by the British Mass Observation project, founded in 1937 by anthropologist Tom Harrison, journalist Charles Madge, and the filmmaker Humphrey Jennings.

Arthur Rothstein was the first photographer appointed by the FSA, a project that was meant to build support for the social reforms of the Roosevelt Administration. He documented the devastating effects of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, a phenomenon caused by a combination of a severe drought and over farming, that lasted eight years and devastated livestock and crops. Described as a social research project and employing as many as 500 volunteers - or "observers" - Mass Observation created "weather-maps of public feeling." The project included documentary photographs from John Hinde, Humphrey Spender, and Michael Wickham and was described as "purely informational and not meant to be artistic in any way." The founders hoped to provide for the British public an "anthropology of ourselves" and the project ran into the mid-1960s and was revived subsequently in 1981.

In the 1960s, meanwhile, art theorist Hal Foster argued that Performance Art, and other emerging trends that broke down the barrier between artist and audience and the definition of institutional space, had moved art toward visual ethnography. Documentary projects of particular communities were often viewed in anthropological terms. However, Foster's argument was that Performance Art directly involved the audience to an extent that they were no longer passive bystanders, and art duly crossed over into the field of anthropology. Artworks like Jeremy Deller's The Battle of Orgreave (2001), in which the artist organized a re-enactment (featuring 800 "re-enactors" and 200 former miners) of a conflict during the 1984 miners' strike, show how the artist works with the community to "recover" its hidden or suppressed history.

War Documentary

War Documentary is thought to have begun in 1848 when John McCosh took photographs of the Second Anglo-Sikh War. McCosh had served as a surgeon in the Bengal Army and went on to document the Second Anglo-Burmese War in 1852. In 1854 both Károly Szathmáry Papp, an Austro-Hungarian artist, and the British photographer Roger Fenton, documented the Crimean War. Fenton, with the endorsement of leading members of the British Royal Family and the British government, became the first Official War Photographer. Given that camera technology still required long exposure times (and therefore could not capture live action) Fenton's images focused on British soldiers and their armaments and encampments. Battle scenes that included dead bodies and/or casualties were considered unseemly and not appropriate for public tastes. Fenton's work was nevertheless credited not only for its impact on War Photography but on the early development of Photojournalism.

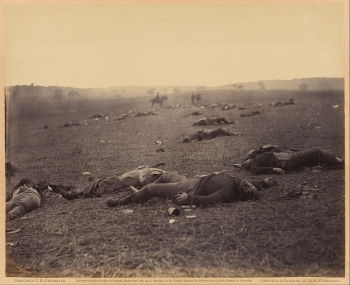

In 1861 Matthew Brady undertook his own project to photograph the American Civil War, hiring a team of photographers that included Timothy O'Sullivan and Alexander Gardner. Brady, at the time the most famous photographic portraitist in the country, turned his attention from his studio in New York to document the war for virtually the whole of its duration. His team's images of battlefields, often strewn with the dead of both sides, of military encampments, and of grueling conditions, were juxtaposed with portraits of leading politicians and military leaders. His 1862 New York exhibition "The Dead of Antietam" was the first time the realities of war and death were seen by the general public and it was greeted with great acclaim.

The early part of the 20th century saw the emergence of small portable cameras capable of capturing action scenes and using film stock that could be developed at the photographer's leisure. This technological development led to extensive photography of World War I as soldiers took the Vest Pocket Kodak to the war front (even though a number of countries, including Britain, forbade the practice). As photographic historian Bodo von Dewitz noted, "After 1916, there were strict rules of what to show and what not. But the pictures from the front, sent by soldiers to their families, could not be controlled that much," resulting, albeit inadvertently, in the most authentic documentation of the war. Governments and their military began appointing official photographers like Ernest Brooks, the first appointed photographer in Great Britain, though Brooks's recreated scenes and faked images played a role in the British government's establishing the "Propaganda of the Facts" to ban staged images in 1916.

With the invention of the hand-held Leica 35 mm camera in 1925, War Documentary became gradually subsumed into Photojournalism. Robert Capa, who made his name by photographing the Spanish Civil War, became one of the most famous war photographers, his images presented in the leading magazines of the day. Other noted photojournalists/war documentarians included Agusti Centelles, W. Eugene Smith, Alfred Eisenstaedt, and Margaret Bourke-White.

Documentary Film

Early films, as exemplified by the likes of Auguste and Louis Lumière, ran at less than a minute long. These "one reelers" were called "actualities" since the movie camera simply recorded an actual event (such as the demolition of a wall); the novelty of photographic images that moved being enough to captivate audiences. It is thought that Documentary Film was first defined as a genre by Boleslaw Matuszewski, a French speaking Polish film archivist who followed his 1896 films of surgical procedures with Une nouvelle source de l'histoire (A New Source of History) and La photographie animée (Animated photography), both exhibited in 1898.

During the first decades of the twentieth century travelogue films, (or "scenics") and city symphony films came into their own. Travelogues depicted exotic locales and peoples, as seen In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914), or more meditative views, as in the earlier Moscow Clad in Snow (1909). As film critic Pamela Hutchinson described them, the city symphony films adopted an avant-gardist approach to documentary. Devoid of characters and plot, the films' "structure [was] borrowed from the movements and motifs of orchestral symphonies or the hours of the day, rather than the dynamics of narrative pacing." A pioneering example of the city symphony approach can be found in Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler's Manhatta (1921). Though the city symphony film declined in the 1930s, the avant-gardist influence continued in films such as Luis Buñuel's Las Hurdes: Tierra sin Pan (Las Hurdes: Earth without Bread) (1933) which brought a surrealist sensibility to an ethnographic documentary focused on a poverty-stricken region in Spain. An early feature-length documentary, Robert J. Flaherty's Nanook of the North (1922), was so successful it established Documentary Film as a commercially viable genre. Though presenting itself as an ethnographic record of the Inuit, the film included staged scenes of an unrelated "family" for dramatic effect, which for some commentators, undermined its authenticity.

Moving into the 1930s, both political film and propaganda film employed documentary with an ideological agenda. Allied with Social Documentary, political films portrayed social issues with a call to political reform, as seen, for instance, in Henri Storck and Joris Ivens's Misère au Borinage (Poverty in the Borinage) (1934). Depicting impoverished coal miners on strike during the Great Depression, the film's opening title read: "Crisis in the Capitalist World. Factories are closed down, abandoned. Millions of proletarians are hungry!" By way of contrast, propaganda films were government sponsored, as seen in the notorious examples of Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia 1 - Festival of Nations and Olympia 2 - Festival of Beauty (1938). Commissioned by Adolf Hitler, and seen by many aesthetes as important artistic achievements (if nothing else), the films' documentation of the 1934 Nazi Party Congress and the summer Olympics of 1936, respectively, were a blatant celebration of Nazi power and ideology.

Documentary Realism, Cinéma Vérité, and Free Cinema

Following World War II, documentary's connection to propaganda led to critical analysis and debate. Italian Neorealism, a film movement based upon the universal values of humanism, informed the development of a commercial film style in Italy known as Documentary Realism. Focusing on ordinary people living in Nazi occupied or post-war Italy, the genre was brought to full fruition by Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City (1945), a film combining several stories of Romans active in the resistance. Two months after the Nazis had been forced to evacuate the city, the director began filming, using an improvisatory approach to both narrative and photographic technique. Though he hired two professional actors (Aldo Fabrizi and Anna Magnani), the rest of the cast were ordinary Italians. Subsequent filmmakers, including Vittorio De Sica's well-known The Bicycle Thieves (1948) worked with nonprofessional casts. De Sica's film, which tells the humble story of a man searching the backstreets and markets of Rome for his stolen bicycle (which he needs for work as a billposter), was further defined by long shots, the use of the handheld camera, a loose narrative structure, and a lack of narrative closure.

Neorealism was championed by André Bazin, a French film critic and theorist, who cofounded the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma (Notebooks on Cinema) in 1951. He felt the camera should be treated as "a window on reality" and argued in favor of depictions of an objective reality where the director became "invisible" and did not manipulate the audience through excessive editing. His ideas were hugely influential on subsequent filmmakers, and by the 1960s cinéma vérité (truthful cinema), led by the French anthropologist and filmmaker Jean Rouch, and the critic Edgar Morin, emerged in France through Rouch and Morin's Chronicle of a Summer (1960).

In Britain, meanwhile, Tony Richardson, Lorenza Mazzetti, Karel Reisz, and Lindsay Anderson founded the Free Cinema movement with the premier of three short documentary films in 1956. Wanting films to be free of both propaganda and the constraints of the commercial film industry, the documentaries, such as Anderson's O Dreamland (1953) were cheaply made using 16 millimeter black and white film stock. The group, who focused on the daily travails of post-war working class communities, favored hand held cameras and rejected all notions of linear narration.

Later Developments - After Documentary Photography

Documentary Photography was challenged in the early 1970s by the dominance of television media with its capacity for live documentation, the closure of leading photo-essay magazines, and postmodernist approaches to art marking. As photographic critic Mark Durden remarked, "from the 1970s onwards, documentary faced a concerted effort to displace its importance. As photography was taken up and used by Conceptual artists, its documentary form was often subject to parody and critique" as seen, for instance, in Sherrie Levine's After Walker Evans series (1981).

Much of the critique of documentary revolved around issues of authorship, appropriation, and was informed by the post-modern awareness that even the earlier documentary projects had been informed by the photographer's perspective, often reflecting cultural values. Though Documentary Photography continued, it tended to do so with a post-modern sensibility, sometimes adopting an ethnographic approach to the communities photographed as seen in Don McCullin's scenes of the urban strife in marginalized neighborhoods, or John Ranard's images of the boxing world in The Brutal Aesthetic (1987). Ranard subsequently went on to photograph the world of Russian prisons in Forty Pounds of Salt (1995) while Puerto-Rican Manuel Rivera-Ortiz documented rural village life in images like Tobacco Harvesting, Valle de Viñales, Cuba (2002). Graciela Iturbide lived among indigenous peoples in remote areas of Mexico, as she documented their way of life, and Sebastião Salgado has become celebrated for his images of workers in Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age (1993), following by his documentation of global migration, The Children: Refugees and Migrant (2000) and Migrations (2000).

Useful Resources on Documentary Photography

-

![Pioneers of Documentary Photography Featured in New Exhibit on "Scientific Charity"]() 2k viewsPioneers of Documentary Photography Featured in New Exhibit on "Scientific Charity"Columbia News

2k viewsPioneers of Documentary Photography Featured in New Exhibit on "Scientific Charity"Columbia News -

![Cotton Mill Girl: Behind Lewis Hine's Photograph & Child Labor Series | 100 Photos]() 318k viewsCotton Mill Girl: Behind Lewis Hine's Photograph & Child Labor Series | 100 PhotosTIME

318k viewsCotton Mill Girl: Behind Lewis Hine's Photograph & Child Labor Series | 100 PhotosTIME -

![Lewis Hine's Photography]() 0 viewsLewis Hine's PhotographyOur PickRevise History

0 viewsLewis Hine's PhotographyOur PickRevise History -

![Envisioning Atget's Paris]() 5k viewsEnvisioning Atget's ParisThe New York Times

5k viewsEnvisioning Atget's ParisThe New York Times -

![Let Us Now Praise Famous Men - Revisited]() 12k viewsLet Us Now Praise Famous Men - RevisitedOur PickPBS

12k viewsLet Us Now Praise Famous Men - RevisitedOur PickPBS -

![The World of W Eugene Smith]() 208k viewsThe World of W Eugene SmithThe Art of Photography

208k viewsThe World of W Eugene SmithThe Art of Photography -

![Graciela Iturbide: The Artist Series]() 72k viewsGraciela Iturbide: The Artist SeriesThe Art of Photography

72k viewsGraciela Iturbide: The Artist SeriesThe Art of Photography

-

![TEDx Talk: Two Views in Documentary Photography: Billy Weeks]() 70k viewsTEDx Talk: Two Views in Documentary Photography: Billy Weeks

70k viewsTEDx Talk: Two Views in Documentary Photography: Billy Weeks -

![Photographer Don McCullin on social documentary photography]() 26k viewsPhotographer Don McCullin on social documentary photographyNatural Science and Media Museum

26k viewsPhotographer Don McCullin on social documentary photographyNatural Science and Media Museum -

![A Layman's Sermon: Jacob A. Riis on How the Other Half Lives & Dies in NY]() 40k viewsA Layman's Sermon: Jacob A. Riis on How the Other Half Lives & Dies in NYMuseum of City of New York

40k viewsA Layman's Sermon: Jacob A. Riis on How the Other Half Lives & Dies in NYMuseum of City of New York -

![Speaking of Art: John Szarkowski on Eugène Atget]() 14k viewsSpeaking of Art: John Szarkowski on Eugène AtgetCheckerboard Films

14k viewsSpeaking of Art: John Szarkowski on Eugène AtgetCheckerboard Films -

![August Sander. Portrait of a Society]() 4k viewsAugust Sander. Portrait of a SocietyTalk by Fabian Knierim

4k viewsAugust Sander. Portrait of a SocietyTalk by Fabian Knierim -

![Knocking around between money, sex, and boredom": Walker Evans in Havana and New York]() 7k viewsKnocking around between money, sex, and boredom": Walker Evans in Havana and New YorkTalk by John Tagg

7k viewsKnocking around between money, sex, and boredom": Walker Evans in Havana and New YorkTalk by John Tagg -

![Nan Goldin in Conversation with Lanka Tattersall]() 16k viewsNan Goldin in Conversation with Lanka TattersallMOCA

16k viewsNan Goldin in Conversation with Lanka TattersallMOCA -

![Lecture: Nan Goldin (2009 Sem Presser)]() 13k viewsLecture: Nan Goldin (2009 Sem Presser)Our PickWorld Press Photo Foundation

13k viewsLecture: Nan Goldin (2009 Sem Presser)Our PickWorld Press Photo Foundation

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI