Summary of Concrete Poetry

Concrete Poetry is perhaps the only significant twentieth-century art movement that is also a significant twentieth-century literature movement. Partly as a result of this, critics have struggled with defining and compartmentalizing it, so it is still less well-known than it might be. Concrete Poetry emerged from the major hubs of Concrete Art in Northern Europe and Latin America during the 1950s and sought to bring the same clarity and simplicity of composition that defined that movement to the written word.

Understood in simpler terms, Concrete Poetry is a kind of linguistic art in which the way words and letters look is as important as what they mean. In such broader view, the movement emerged from a long historical tradition and inspired far more diverse and globally dispersed tendencies, melding with advances in Anglo-American literary modernism and Performance Art, amongst many other things. Today Concrete Poetry is perhaps unique amongst avant-garde literary movements in being more popular outside academic institutions than within them, and is ironically better-known than the movement that inspired it, Concrete Art.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The most immediately recognizable characteristic of Concrete Poetry is the arrangement of language in visual form. Words, letters, and other linguistic material are deployed as a visual compositional tool in a manner that was initially inspired by the Concrete Art movement. Indeed, the first Concrete Poets, many of whom were closely connected to Concrete Artists, often borrowed elementary visual designs directly from Concrete Art pieces, arranging letters in grids, columns, spirals, or other basic visual forms.

- Concrete Poetry reduced the linguistic element of poetry to an absolute minimum. As a late movement in Literary Modernism, it was responding to the challenge of first-generation modernist writers who had stressed complexity and linguistic expansiveness as means of experiment. Concrete Poets struck out in the opposite direction, presenting poems in which just one of two words, arrestingly laid out, could encapsulate a whole credo.

- Concrete Poetry stood for a post-World War II spirit of internationalism, optimism, and cross-cultural communication. Working in the wake of global conflict, the Concrete Poets were inspired by modern art and architectural movements such as Concrete Art and the International Style, which had defined global vocabularies for their respective media. The Concrete Poets were interested in creating a similar, International Style for language.

- Although its origins were in Concrete Art, Concrete Poetry became closely associated with developments in Performance Art such as the emergence of Fluxus and Happenings. In troubling the boundaries between linguistic and visual expression, the Concrete Poets were pushing at the boundaries between artistic media that had been established by earlier theorists of Modernism such as Clement Greenberg, in the same way that Intermedia, Performance-based artforms were attempting.

Artworks and Artists of Concrete Poetry

Silencio

Eugen Gomringer's "Silencio" is perhaps the quintessential example of Concrete Poetry in its early or classical guise, its semantic minimalism and elementary visual form strongly informed by the aesthetics of Concrete Art. A frame formed from the title word repeated fourteen times - subtly alluding to the fourteen lines of a sonnet - the poem shapes a blank central space which comes, by implication, to stand for the quality of "silence" evoked by the language. Though the effect is realized on an ostentatiously small scale, the interaction of visual and linguistic form in this poem is foundational to the stylistic aims of early Concrete Poetry as a whole. The visual space would not evoke "silence" were it not for the hint provided by the words while the words seem somehow infused with the ambient effect of the visual form.

"Silencio" was published in 1953 in Gomringer first collection of Concrete Poetry, entitled Konstellationen in reference to Stéphane Mallarmé's descriptions of his poems as "constellations". A Bolivian-born Swiss poet, in his youth Gomringer had written poems in a range of styles, including sonnets and Symbolist-influenced verse. The influence of Concrete Art on the new, visual style of poetry Gomringer began to develop in 1952 is neatly signified by his employment from 1953 onwards as secretary to the Concrete Artist Max Bill at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, a post-war hub of Constructivist and post-Bauhaus aesthetics. At the same time, there are other creative contexts to mention in relation to Gomringer's poem. John Cage's 'silent' composition, 4'33", was first performed the previous year. In fact, in responding to the theme of silence through literature Gomringer was ruminating on the limits of subjective expression the same way as artists across a range of media.

There was, moreover, a political subtext to this preoccupation with silence which can be emphasized by comparing Gomringer's withdrawal from linguistic expression with the idiosyncratic, elusive poetry of the Romanian-born German writer Paul Celan, a survivor of the Holocaust. For both poets - though with a far more urgent basis in reality in Celan's case - eschewing a language of personal communication was partly a way of alluding to traumas so profound that they could not be expressed. The poet and critic Steve McCaffery has written about the related connotations of political silence in Gomringer's poem: a general unwillingness within post-war Western, and particularly German, culture to confront the brutality of its recent past.

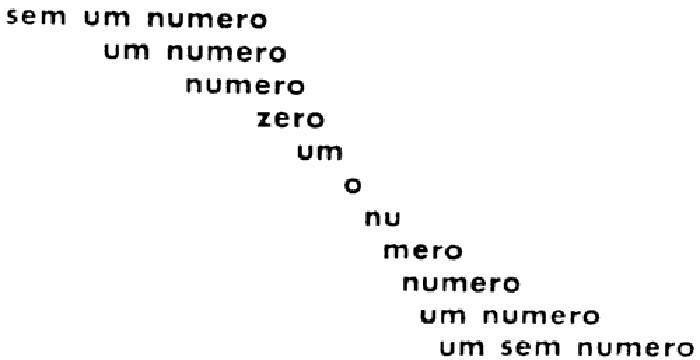

Sem Um Numero

Augusto de Campos's poem "Sem Um Numero" ("Without a Number" in Portuguese) consists of a twisting shape formed from several permutations of the title phrase, spelled out in sans serif, International Style type. The phrase gradually contracts as the lines shift down and inwards. On the fourth line, the only remaining word, "numero", is replaced with "zero", which is recreated as a numerical symbol, 0, at the center of the page. Beyond this point the lines start to expand, but into a different phrase, "Um Sem Numero" ("numberless"). As with much of the Noigandres poets' early work, one phrase evolves into another which, though grammatically and phonetically similar, has a very different meaning, with the zero symbol at the center of the page standing by implication both for absence and for the idea of infinity as numberlessness.

Augusto de Campos was one of the three founding members of the Noigandres poetry group established in São Paulo in 1952, along with his brother Haroldo de Campos and their friend Décio Pignatari. The Noigandres very earliest Concrete Poems were similar in import to Gomringer's, focusing on linguistic reduction and elementary visual arrangement, but from an early stage they were more concerned than Gomringer with incorporating wordplay and double meanings into their poetry. By the late 1950s this had developed into an interest in tackling political, social, and cultural themes, often using minute shifts in grammatical form to exact radical shifts in meaning which relayed polemical messages.

In this case, as the critic Willard Bohn has pointed out, the phrase "Without a Number" is not simply an evocation of an abstract quality of unknowability, but a reference to the social and cultural exclusion of much of Brazil's rural, peasant population from national society. In particular, they had been left out of a recent government census and were thus excluded from welfare programs. In this context, the phrase "Numberless" comes to refer to the size of this dispossessed population. Over the coming years, the Noigandres' work would become more and more politically engaged and responsive to pop culture, culminating in Augusto's case with his "Popcrete" poems of the early 1960s.

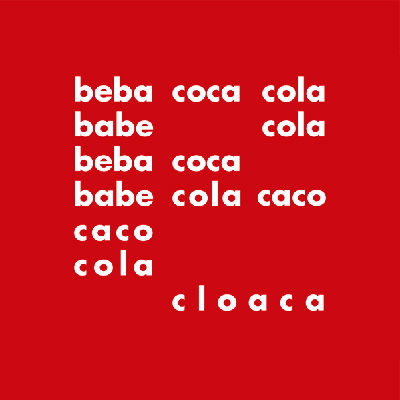

Bebe Coca Cola

In this poem by a founding member of the Noigandres group, the phrase "Bebe Coca Cola" (Portuguese for "Drink Coca Cola") mutates over several lines to produce a set of ironic and subversive variations on that imperative. Separated from its partner word "Coca", the word "Cola", isolated on the second line, translates as "glue", while the other amputated section of the brand-name, "Coca", comes to refer to a different kind of stimulant, cocaine. These reworkings of an incessantly repeated marketing slogan suggest the insidious power of advertising culture, while on the following lines, "babe" and "caco" - "drool" and "shard" - offer further references to addiction and degradation. On the closing line, the word "cloaca", roughly translatable as "waste", "rubbish dump", or "cesspool", offers a forcefully grim closing image, emphasized by the space surrounding it. The coloring of the poem, in the red and white of the Coca Cola brand, adds to the overall quality of deadpan satire.

Décio Pignatari's critique of North American advertising culture may partly reflect his own training as an advertising designer. More generally, it is indicative of a shift in the compositional and thematic approach of the Noigandres poets during the late 1950s, which was also responsible for inspiring Augusto de Campos's "Sem um Numero". As in that poem, minute shifts in grammatical form generate radical shifts in connotation - as in the "bebe"/"babe" contrast (from "drink" to "drool") - while the absence of a first-person narrative voice (an "I") means that the poem avoids the quality of dogma or self-righteousness, making the political message more striking and convincing.

The broader cultural context for the composition of this poem is the expansion of North American companies into Latin American consumer markets in the decades following World War II, a process which the hugely successful Coca Cola brand came to embody. As the only major Western power to emerge from the war with its economy in good shape, the US was able to consolidate its economic and cultural domination over many other parts of the world during this period. In the late 1960s, Décio Pignatari would translate the work of communication theorist Marshall McLuhan - who had offered critiques of the hypnotic power of advertising culture during the early 1960s - into Portuguese, showing his ongoing engagement with themes of consumerism and North American cultural imperialism.

Pik Bou

Writing about this poem in Emmett Williams's 1967 Anthology of Concrete Poetry, the French poet Pierre Garnier noted that it was based on the regional dialect of his native Picardy region, in particular the local term for "Green Woodpecker", "Pik Bou", or "Pivert" in French. Set inside a circular frame, variants of the onomatopoeic title word - meaning that the word mimics the sound of the thing it refers to - skip in uneven lines down the page: "ik pik epeke pik epe/pik bou pik bou pik bou pi". As in many early Concrete Poems, the visual form has no direct symbolic relation to the semantic theme of the poem. For Garnier, visual composition was often used in an Expressionistic or, as he put it, "Spatialist" way to complement the phonetic and subliminal meanings of the words.

Pierre Garnier was born in Picardy, a region of North-Eastern France roughly demarcated by Paris and the English Channel, in 1928. He was one of the first poets outside of Concrete Poetry's initial hubs in Germany and Brazil to both respond to and substantially develop the idiom of the movement. He had produced poetry across a range of styles during the 1950s but in 1962 he composed his "Manifeste pour une Poésie Nouvelle, Visuelle et Phonetique" ("Manifesto for a New, Visual and Phonetic Poetry") signifying a shift in his style of work. In 1963 he circulated a statement entitled (in English translation) "Position 1 of International for Spatialist Poetries" to his new contacts in the international Concrete Poetry movement. This statement aimed to collate recent developments in Concrete, Visual, and Sound poetries worldwide. By the time it appeared in the journal Les Lettres the following year it had gained 25 signatories, from Germany, Austria, England, Belgium, Brazil, Scotland, Finland, France, Holland, Japan, Portugal, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, and the United States.

Garnier's own work, often created in collaboration with his partner Isle Garnier, was unique. His expressionistic arrangements of language-forms were quite distinct from the geometrical patterning of the first German and Brazilian Concrete Poems. Garnier was also interested in how Concrete Poetry could be used to preserve regional and historical dialects, by employing the kind of playful, onomatopoeic words that those dialects tended to preserve. Writing about "Pik Bou" in Williams's anthology, he noted: "[i]n general, dialects, old languages which live despite bureaucratization, have retained important concrete reserves, while the so-called national languages have developed an abstract vocabulary." For Garnier, then, as for the Scottish poet Edwin Morgan and the so-called Vienna Group of Austrian Concrete Poets, Concrete Poetry was an art of regional self-definition as much as global interaction.

Kawa mata wa Shū

This beautiful 1966 work by the Japanese Concrete Poet Seiichi Niikuni, generally translated as "River/Sandbank", offers a minimal visual representation of the landscape evoked by the two "ideographs" - written symbols that represent an object or idea directly rather than, or as well as, standing in for a sound - used to create it. The top-left half of the square frame is formed from repetitions of the symbol for "River", while the bottom-right section is formed by the similar but more closely striated symbol for "Sandbank". These two interlocking triangles, together with the hint provided by their semantic meaning, represent a river rushing past a precisely hewn bank of sand, the aligned strokes which comprise each symbol enhancing the overall impression of rushing water. In fact, the piece can be seen to visually represent what it describes in two ways: both as an overall visual form and through the pictorial function of each individual ideograph. Like many East-Asian writing systems, the Kanji language system - a Japanese writing system based on Chinese - has visible roots in pictography: writing systems which relay their objects through visual representation.

Born in 1925 in Sendai, in the north of Japan's central island of Honshu, Seiichi Nikuni was a leading member of several avant-garde poetry groupings in his home city before turning to Concrete techniques after moving to Tokyo in 1962. In 1963 he published a collection of visual poems called Zero-On, and in 1964 he co-founded a group called ASA (Association for the Study of Art) with the aim of exploring Concrete techniques and introducing the work of the international Concrete Poetry movement. The group magazine, ASA, published poems by Haroldo de Campos in Japanese, and Niikuni's contacts through the group eventually brought him to the attention of Pierre Garnier. The result of this encounter was the collaborative 1966 collection Poèmes Franco-Japonais ("Franco-Japanese Poems") for which "River/Sandbank" served as the cover poem. The Franco-Japanese poems consist of chunks of text formed from repeated Kanji symbols, arranged into interlocking and overlapping shapes on the page, often through the Expressionistic cutting and collaging of strips of paper.

It is unsurprising that a vibrant Concrete Poetry movement developed in Japan, given the propensity of the Kanji language to visual expression. There was a long history in Modernism and Modern Art of taking the Chinese writing system as a point of inspiration for literary and artistic experiment. The North-American modernist poet Ezra Pound was strongly influenced by the linguist Ernest Fenollosa's famous study The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry (translated by Pound in 1936), which held, not entirely correctly, that Chinese writing provided a "vivid shorthand picture" of the objects to which it referred. In producing Concrete Poems using an ideographic writing system adapted from Chinese, Niikuni was thus responding to an established cross-continental tradition.

Forsythia

In this poem, Mary Ellen Solt arranges an anagrammatic poem in the shape of the flower to which it refers. It is one of a whole collection of such poems entitled Flowers in Concrete, published by 1966, which bring a unique range of influences and thematic associations to the Concrete Poetry movement. Solt's poem is notable for its linguistic and lyrical skill and subtlety as compared to the work of many of her peers in the Concrete movement, and for its concern with nature and the subtleties of personal emotion rather than with abstract concepts or qualities.

Mary Ellen Solt was one of the most talented poets associated with the Concrete Poetry movement, and one of the few women poets or artists who engaged with it. Born in 1920 in Iowa in the United States, she moved in 1955 moved to Bloomington when her husband Leo gained a job as a history lecturer at the University of Indiana. This indirect connection to the University allowed her to attend the prestigious School of Letters summer school in 1958, through which she established a correspondence with the famous American modernist poet William Carlos Williams, becoming both his friend and a perceptive critic of his work. This, along with her ongoing connection to Indiana University, allowed her to develop her own work as a poet and critic over the following decade. Flowers in Concrete was published by Indiana's fine art department in 1966, perhaps as a result of which, she was invited to guest-edit an issue of the Spanish language art journal Artes Hispanicas on the Concrete Poetry movement. This became the highly influential anthology Concrete Poetry: A Worldview, republished as a stand-alone book in 1970, which included Solt's still-definitive, country-by-country introduction to the movement.

Solt had initially turned to the visual arrangement of language-forms in her poetry out of a concern, influenced by William Carlos Williams, with using the visual arrangement of words to map the rhythms of speech, particularly regional and non-standard variants of spoken English. In her 1983 article "William Carlos Williams: The American Idiom" she referred to Concrete Poetry as "part of the legacy [Williams] left". Though this presents an Anglocentric view on Concrete Poetry as an international art movement, there is no doubt that Solt, along with the Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, was amongst the most talented poets who embraced Concrete Poetry as a way of mapping the music of spoken language.

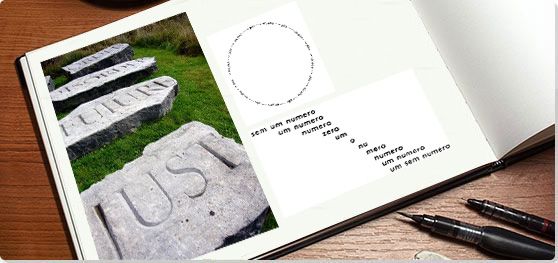

The Present Order is the Disorder of the Future - Saint Just

This striking poem-sculpture, installed in Ian Hamilton Finlay's poetry garden, Little Sparta, in the Pentland Hills south of Edinburgh, is a monument both to Finlay's own singular artistic vision and to the grandest ambitions of the Concrete Poetry movement. A phrase from the French Revolutionary Louis Antoine de Saint Just is inscribed into a set of enormous stone slabs set into a rising fold of land at the rear of the garden, framing a view of the loch which Finlay had himself dug out during the late 1960s, and the heather-strewn hills beyond. The statement is granted a sense of authority and gravitas through its inscription in stone, indicating the way in which the visual presentation of the Concrete Poem could enhance the quality and ambience of the linguistic message. The Present Order is one of a huge number of such works installed throughout Finlay's garden, forming a series of distinct environments or, as Finlay called them, "interiors", framed by trees, paths, and waterways. The work was first displayed at the Hayward Gallery's Sculpture Show in 1983, and versions have also been installed in the grounds of the Cartier Institute in Paris and in the Parc Güell in Barcelona.

Ian Hamilton Finlay had practiced as a painter and writer during the 1940s and 1950s but, like many of his compatriots in the international Concrete Poetry movement, he started creating work in a radically different style during the early 1960s. His first Concrete Poetry collection, Rapel, was published in 1963, inspired by the work of the Noigandres poets. Across the 1960s Finlay greatly developed the form of the poem-sculpture, creating linguistic works set in glass, wood, metal, and stone. In 1966 he moved to Stonypath Farmhouse (renamed Little Sparta as a rebuke to Edinburgh's reputation as "The Athens of the North") and began to convert the grounds into an interactive, walkthrough environment populated with poems inscribed on objects and surfaces of every kind: from gateposts to columns to stone birdbaths.

Finlay used Concrete Poetry's connotations of truthfulness and clarity to engage with the ideologies of revolutionary politics and Classicism which endorsed similar notions of purity. The use of a Saint Just quote in this poem is particularly instructive. Saint Just was a loyal follower of Robespierre, the most uncompromising of all the insurgents of the French Revolutions - it was Saint Just who in 1793 began to issue the decrees for executions and purges that came to characterize the period of Revolutionary history known as "The Terror", seen to signify the souring of its ideals. Finlay thus offers an uncompromising comment on the relationship between the aesthetic order signified by Concrete Poetry and the kinds of social order enforced through political extremism.

Etched granite slabs - Little Sparta Trust, Dunsyre, Edinburgh, Scotland

Beginnings of Concrete Poetry

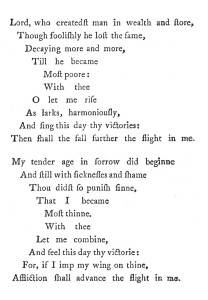

The act of presenting language as a visual entity has a vast and unwieldly history stretching back to the dawn of civilization and of modern writing systems, all of which evolved from pictography: from writing systems which represented things visually rather than phonetically. Arabic calligraphy, Chinese written characters, and medieval pattern poems from the Western Christian tradition all played their role in establishing this heritage; so too did the technopaegnia of Ancient Greece, emulated in the seventeenth century by the Metaphysical Poet George Herbert.

However, it is generally acknowledged that a concern with the visual representation of language in the modern era originates with French Symbolist Literature of the late nineteenth century, in particular the writing of Stéphane Mallarmé, whose 1897 poem Un Coup de Dés utilized typographical arrangement in a way that totally broke from early traditions of picture and pattern poetry.

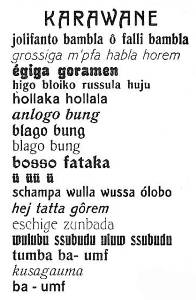

In the first decades of the twentieth century, these early advances were picked up by the more iconoclastic spirits of the Futurist and Dada movements. Poet-polemicists and artists such as F.T. Marinetti, Hugo Ball, and Kurt Schwitters stressed both the visual appearance and the sound of language - often writing and performing nonsense poems arranged chaotically on the page - as a way of undermining rational thought and expression. In an era of war and rapid technological development, breaking apart and rearranging language encapsulated both the anxieties and the excitement of the age. The French poet and critic of Cubism Guillaume Apollinaire, a brief fellow-traveler of the Futurists, also created a series of famous visual poems or "calligrammes" in the shape of buildings and objects such as the Eiffel Tower.

This early-twentieth century explosion of visual poetry died away with the great early-twentieth-century avant-gardes: Futurism, Dada, Constructivism. Meanwhile, in the world of literature, the emergence of extremist politics in the 1930s and, ultimately, World War II, ushered in an era of more sober, realistic writing.

From Concrete Art to Concrete Poetry

After World War II poets and artists in Europe were looking to both rebuild national and international culture and to reclaim the legacies of the avant-garde movements whose development had been stemmed by political turmoil. It was in this spirit that Concrete Art and modernist architecture came fully into flower in the West, as movements which reignited the ambitious, abstract styles of the early twentieth century and sought to establish new, rational, international languages for creative expression.

The Concrete Artist Max Bill, with associates including Inge Scholl, sister of the murdered White Rose Movement leaders Hans and Sophie, established the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, West Germany in 1953 as a kind of second Bauhaus, and crucible of cultural rebirth. The aim was partly to reignite the tradition of rational abstract art and functional design that had defined the Bauhaus prior to its closure by the Nazis in 1933. It was here that the young Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer secured a job as Bill's secretary. Gomringer's work was already expressing the same logic of rational experiment as characterized the Hochschule's faculty of architects, graphic and industrial designers - he had created his first Concrete Poem, "Avenidas", in 1952, though he would only define it as a Concrete Poem three years later. Gomringer's early compositions stressed the use of minimal linguistic elements and the repetition and arrangement of language in simple patterns on the page.

The South American Context

Meanwhile, in post-war Brazil, the influence of Concrete Art was being felt equally strongly. The Latin American continent had benefited from an influx of Constructivist-influenced artists fleeing the conflict in Europe, whose presence invigorated the existing abstract art scene that had been spearheaded since the 1930s by artists such as Joaquín Torres-García, resulting by the late 1940s in the founding of groups such as Asociacíon Arte Concreto-Invencíon and Arte Madí in Argentina. By the 1950s Brazil was going through a period of rapid economic and industrial development, and Concrete Art seemed to epitomize a new spirit of rational optimism within the country. This led to the emergence of groups such as Grupo Ruptura in São Paulo and Grupo Frente in Rio de Janeiro. Brazil also proved fertile ground for architects working with the techniques of large-scale rational functional design spearheaded by Le Corbusier and others earlier in the century. The most famous result of this was the construction of Brazil's new capital, Brasília, by Le Corbusier's acolyte Oscar Niemeyer between 1956 and 1960.

In this atmosphere, three poets based in São Paulo - the brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos and their colleague Décio Pignatari - were inspired to create a new style of poetry that would embody the principles epitomized by South America's emergent Concrete Art scene. Calling their group Noigandres, after a line from an Ezra Pound poem, they created their first poems in 1952, the same year that Gomringer had begun independently to create Concrete Poems in Europe. The Noigandres poets struck upon a similar range of techniques, stressing the minimum use of words, simplicity of grammatical constructions, and abstract visual arrangements of language. However, their work quickly became more concerned with exploring double meanings and wordplay, and with tackling political and social themes.

A Movement Defined

In 1955 Décio Pignatari met Eugen Gomringer at Gomringer's workplace, the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. The two poets realized that they were producing work that was identical in fundamental respects, and they agreed to forge an international poetic style to be called "Concrete Poetry". Gomringer wrote his first manifesto for Concrete Poetry in 1956, intended to serve as an introduction for an anthology - though this never appeared. The Noigandres poets first referred to their work publicly as Concrete Poetry in an exhibition of Concrete Art held at São Paulo's Museum of Modern Art later that same year.

Concepts and Styles

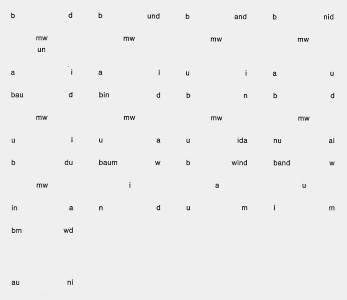

The Concrete Poetry produced by Eugen Gomringer and the Noigandres poets from the early to mid-1950s was defined by certain key characteristics: small groups of words or letters were arranged in iconic patterns on the page, often using repetition (thematic, phonetic, and visual) as a way of suggesting the fundamental truthfulness or accuracy of the words presented. Aspects of graphic presentation, including the use of certain sans serif Modernist fonts such as Helvetica and Futura, also became key stylistic aspects of the genre. It was a highly unusual move for a literary movement to define itself by such means - it is partly in this sense that Concrete Poetry can be considered a movement in modern art and design as well as modernist literature.

Internationalism: The Movement Spreads

Concrete Poetry aimed to define a type of poetry that, like International Style typography or Modernist architecture, could be reproduced in any given cultural context without loss or distortion of meaning. As such, the first proponents of the movement were always keen that its influence would spread around the world, and writers and artists in far-flung locations were keen to respond to this challenge.

From the mid-1950s onwards, poets and artists based all over the globe started communicating with Gomringer and the Noigandres poets, responding to their new techniques for literary creation. Others who had already been working in similar styles found a new context for their work. In Germany there was the so-called Darmstadt Group, including the German Claus Bremer, North American Emmett Williams, and Swiss Daniel Spoerri, while in Stuttgart a collective sprung up around the poet and theorist Max Bense, including Hansjörg Mayer, Helmut Heißenbüttel, and Reinhard Döhl. In Austria, a school of poets referred to as the Vienna Group, including Gerhard Rühm, Ernst Jandl, and Friedrich Achleitner, had already been creating poems in a Concrete idiom, while focusing more on political themes and intermedia art events. The only major grouping of Concrete Poets to emerge behind the Iron Curtain was based in Czechoslovakia. This group, including the collaborative duo of Josef Hiršal and Bohumila Grögerová, were similarly concerned with turning Concrete Poetry to political ends, in response to the recent political history of their country.

In Brazil, an alternative group to the Noigandres poets emerged in Rio de Janeiro, partly inspired by the work of Wlademir Dias Pino, who had been practicing in a style very similar to Concrete Poetry prior to the Noigandres group, and partly by the local Grupo Frente of Concrete Artists. It was from the Carioca group - those based in Rio de Janeiro - that the first significant challenge to early concrete style arose, in the form of Ferreira Gullar's "Neo-Concrete Manifesto" of 1959, which defined a more intuitive, spontaneous approach to Concretism across art and literature, paving the way for the Neo-Concrete Art of Lygia Clark and others. At the same time, the Noigandres approach presaged the larger and more creatively diverse style of the Invenção group, which included Ronaldo Azeredo, Edgard Braga, José Lino Grünewald, Pedro Xisto and others. Developments within this group included Semiotic Poetry, which used non-linguistic symbols, as if to suggest the development of entirely new writing systems.

In the Anglophone world, particularly North America, Concrete Poetry had been picked up by the early 1960s by writers frustrated with the conservatism of much 1950s English language poetry. These poets were turning back to the stylistic innovations of early-twentieth-century Modernist writers such as Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and William Carlos Williams. Pound and Williams were interested in using the placement of words on the page to suggest the rhythm of speech, so there was a natural overlap with the ethos of Concrete Poetry, which also stressed the visual arrangement of words. Moreover, in North America this tradition had never really died, having been carried forwards by subsequent generations of poets connected to Objectivism or the Black Mountain School, such as Charles Olson, Lorine Niedecker, Louis Zukofsky, and Robert Creeley. North American Concrete Poets such as Mary Ellen Solt, Jonathan Williams, Robert Lax, and Ronald Johnson were therefore responding to twin influences: both the challenge of the international movement and their own national Modernist literary tradition. Beat poets such as Gregory Corso and cut-up poets such as William Burroughs and Brion Gysin had also produced visually informed work and were responding in a different way to the same precedents.

In Great Britain, and particularly Scotland, poets such as Ian Hamilton Finlay and Edwin Morgan began using concrete techniques. Like their North-American counterparts, they were partly interested in embracing the innovations of early-twentieth-century North American poetry, and were frustrated by what they perceived as the formal conservatism of their native traditions: particularly with poets associated with the English literary grouping known as "The Movement", notably Philip Larkin. Finlay would go on to create a garden full of poem-sculptures, Little Sparta, that stands as one of the most remarkable monuments to the ethos of Concrete Poetry.

Other significant international groupings of Concrete Poetry emerged in countries including France, where Pierre and Ilse Garnier developed a version of Concrete Poetry that they called Spatialism. Concrete Poetry also found fertile ground in Japanese literary and artistic culture. Many East-Asian writing systems had an inbuilt affinity with concrete techniques because of their strong basis in pictography - the visual rather than phonetic representation of objects and concepts - so Japanese Concrete Poets such as Seiichi Niikuni and Kitasano Katué had a particularly rich vein of compositional material to draw from in creating their work.

The literary critic Marjorie Perloff has suggested that what bound all of these cells of the early Concrete Poetry movement was that each of them was concentrated in one of the "smaller or marginalized nations of the post-war", far from the beleaguered war capitals. In modern art and particularly in modernist literature, with the notable exception of the USA, it was perhaps left to (economically) smaller, often newly emergent nations, defining themselves against an international cultural scene suddenly freed from the influence of major imperial and military powers, to carry the spirit of invention forwards.

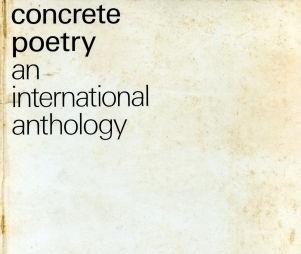

The Concrete Poetry movement in this classical giuse had spent its energies by around the close of the 1960s, perhaps as the Utopian projects in Modernist Architecture and Concrete Art to which it was responding also waned. Three major anthologies of Concrete Poetry appeared in 1967-68, Stephen Bann's Concrete Poetry: An International Anthology (1967), Emmett Williams's An Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967), and Mary Ellen Solt's Concrete Poetry: A Worldview (1968). According to the critic Stephen Scobie, "the very definitiveness of these anthologies 'froze' concrete poetry in its historical moment." A major group retrospective of Concrete Poetry, entitled ?Concrete Poetry, was held at Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum in 1971, and has been taken as a pragmatic marker of the end of the Concrete Poetry movement in its first form by critics such as Jamie Hilder.

Concrete in Context: Connections to Other Art Movements

Although the Concrete Poetry movement in a strict sense can be seen to have died away by the early 1970s, from the late 1950s it had also been expanding exponentially in multiple directions, most of them extending well beyond the boundaries just defined, many of them into the 1970s and beyond. Concrete Poetry outlived its own death partly because it was swept up in a broader wave of experiment within the world of literature and, particularly, modern art, which was concerned with mapping the boundaries and overlaps between language and other expressive and communicative media.

This is evident, for example, in the way that Abstract Expressionist paintings by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Cy Twombly, and Mark Tobey, began to incorporate symbols that looked like letters or pictographs; the way that Pop Artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Roy Lichtenstein incorporated text and image in their work in the form of collages or cartoon strip-style visual frames; and the emergence of Conceptual Art, which often relied on compositional maneuvers similar to Concrete Poetry. Though Conceptual Art's motives for integrating language into art were, at root, very different - leading the Conceptualist Joseph Kosuth to deride Concrete Poetry as "cute with words but dumb about language" - some Conceptual Artists, such as Carl Andre and Lawrence Weiner, began to incorporate genuinely lyrical linguistic sensibilities into their work.

Amongst the art movements with which Concrete Poetry became even more closely associated were Performance Art, specifically "Intermedia Art" as defined by the Canadian artist and theorist Dick Higgins through a series of manifestos in the late 1960s. This style of art was closely associated with the Fluxus movement and with the practice of Happenings, which were in turn rooted in the experimental musical performances of composers such as John Cage, who staged his first Happening at Black Mountain College in 1952.

The theory of Intermedia Art, in Higgins's conception, held that the boundaries between different artistic media were the product of social and economic structures that were historically and culturally rooted, and which would die away with the emergence of a new, radical society. Intermedia Art could help usher in this new phase of society by breaking down the barriers between different artistic media. It is for this reason that many Fluxus art performances and Happenings refused to adhere to any pre-ordained rules or structures, and were intended to unfold in a range of directions, passing, for example, between the genres of theater, musical performance, poetic recital, and political rally.

Higgins saw in Concrete Poetry what he called "an Intermedium between poetry and the fine arts" and sought to present it as part of the movement. His Something Else Press published Emmett Williams's Anthology of Concrete Poetry in 1967, which helped to popularize this understanding of Concrete Style. This culminated in a version of Concrete Poetry that was indebted to Dada techniques, stressing spontaneity of composition, the live performance of Concrete Poems, and a movement away from words and letters towards a form of expression that genuinely occupied the threshold between the literary and the visual.

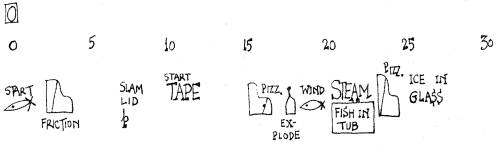

Concrete Poetry and Sound Poetry

At the same time, for many artists and poets, Concrete Poetry became closely associated with Sound Poetry, a kind of performed poetry or sound art in which the way language sounded was as important, or more important than, what it meant. This could extend to wholly nonsensical 'poems' created by performing abstract visual scores, or collaged vocal works produced on tape reel, somewhat akin to Musique Concrète. Like Concrete Poetry, Sound Poetry had a vast prehistory stretching back to the oral rituals and games of pre-literate and tribal communities, but had been most fully defined during the Avant-Garde heyday of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, especially by the Futurists and Dadaists, with Kurt Schwitters majestic vocal symphony Ursonate (1920-32) standing as its most lasting monument.

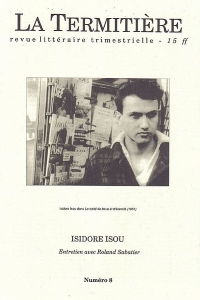

After the war, poets and artists in France such as Isodore Isou - who defined a Dada-influenced movement called Lettrism - and Henri Chopin, who broke from the group around Isou to form the Ultralettrist movement, began to extend the effects of Sound Poetry by creating new alphabets and language systems, and by manipulating the sound of the voice using tape recorders and other newly available technology. A similar group emerged in Sweden, where in 1953 the artist Öyvind Fahlström had written a manifesto for Concrete Poetry followed by a series of poems, both of which were only discovered by the existing Concrete Poetry movement towards the end of the 1960s. Fahlström worked in isolation from the Brazilian and German poets and was concerned with the sound of language and the use of onomatopoeia. Following this, during the 1960s, the Fylkingen Research Institute in Stockholm supported the emergence of a Sound Poetry movement connected to Concrete Poetry, spearheaded by artists, poets and composers such as Sten Hanson and Åke Hodell. In London, a similar group emerged around the poet and artist Bob Cobbing and his press and performance group Writers Forum, and in Canada around Steve McCaffery, bpNichol, and the so-called Toronto Research Group.

Through its cross-pollination with these and many other movements in Modern Art, Modernist Poetry, and even experimental music, Concrete Poetry survived as a thread of influence if not a distinct, coherent movement well beyond the early 1970s. Many writers and artists continue to cite the influence of Concrete Poetry on their work up to the present day.

Legacy

The range of directions in which Concrete Poetry developed, and its difficult placement between a range of different genres (most obviously visual art and literature) makes it very difficult to trace its legacies from the 1970s onwards.

Limiting our focus to modern art, one of the most significant movement to build on the compositional frameworks laid down by Concrete Poetry was Digital Art. Many of the important early exponents and critics of Concrete Poetry, such as Haroldo de Campos and Max Bense, were also attuned to early developments in computer technology, and were interested in exploring the connections between Concrete Poetry and computer coding. Both pursuits, in a sense, involved devising new language systems through which existing languages could be encoded and simplified. The connection is particularly clear with types of Concrete Poetry using invented language systems, such as Semiotic Poetry, which was devised by Brazilian poets including Luiz Ángelo Pinto and Décio Pignatari in the early 1960s.

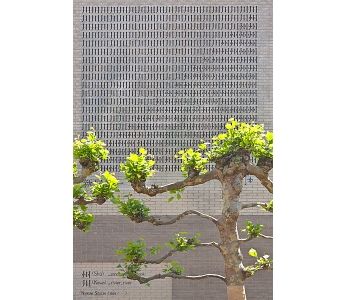

Publishers such as Hansjörg Mayer included serial artworks created using algorithmic computer sequences alongside their roster of published Concrete Poets, while Max Bense's workplace, the Technischen Hochschule in Stuttgart, fostered the work of a range of poets and artists, such as Frieder Nake, operating at the boundaries of Digital Art and Concrete Poetry. In 1968 the trendsetting exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity, held at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London and curated by Jasia Reichardt, presented examples of Digital Art and Concrete Poetry side by side. The influence of Concrete Poetry on Digital Art can be sensed today in the language-based practices of groups such as the Seoul-based Digital Art collective Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries.

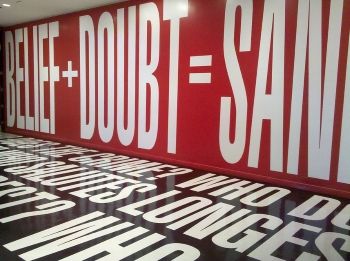

There is also a history of interaction between Concrete Poetry and Post-Conceptual art, as evident, for example, in the work of Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Working in the wake of Concrete Poetry as well as the better-known paradigm of Conceptual Art, Holzer and Kruger utilize visually arresting linguistic arrangements, often in conjunction with photographic images or sculptural forms, to present politically and culturally charged slogans mimicking and subverting the techniques of advertising.

British land artists such as Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, meanwhile, explored the complementary relationship between language, image, and visual symbolism in their mapping and documentation of event and land-based practices. These artists were in contact with British Concrete Poets during the 1960s and the two schools can be seen to have mutually informed each other. The Concrete Poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay, through the construction of his extraordinary poet's garden, Little Sparta, in the Pentland Hills south of Edinburgh, developed probably the most sophisticated oeuvre at the boundaries of Concrete Poetry and land-based sculptural practice.

Within the world of literature, Concrete Poetry's threads of influence spread far and wide. Perhaps most notably, it has strongly informed contemporary North American avant-garde movements such as Conceptual Poetry, associated with the writers Kenneth Goldsmith and Christian Bök. Concrete Poetry's influence can also be sensed across a whole sweep of new media poetries (poetry which explores the linguistic possibilities of new and emerging technology) as in the work of the Brazilian-American artist and poet Eduardo Kac.

Useful Resources on Concrete Poetry

- Concrete Poetry: An International AnthologyOur PickBy Stephen Bann

- The New Concrete: Visual Poetry in the 21st CenturyBy Victoria Bean and Chris McCabe

- Mary Ellen Solt: Toward a Theory of Concrete PoetryBy Sergio Antonio Bessa

- Reading Visual PoetryBy Willard Bohn

- Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971By Jamie Hilder

- Unoriginal Genius: Poetry by Other Means in the New CenturyBy Marjorie Perloff

- Earthquakes and Explorations: Language and Painting between Cubism and Concrete PoetryBy Stephen Scobie

- Concrete Poetry: A World ViewOur PickBy Mary Ellen Solt

- Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and ScotlandBy Greg Thomas

- An Anthology of Concrete PoetryOur PickBy Emmett Williams