Summary of Contemporary Realism

Contemporary Realism emerged out of New York in direct defiance to the prevailing popularity of Abstract Expressionism. The movement signified a return to a straightforward representation of life via figurative artworks. A loosely connected and disparate group of initial artists borrowed heavily from roots embedded earlier by the 19th century Realist painters who aimed to depict the real rather than the ideal. Yet these new artists, proficient in modern art, employed this mission in a decidedly fresh fashion that built upon tradition while incorporating a contemporary sophistication and techniques in line with the current times. Reality suddenly became cool again swathed in the unique perspectives of artists working with, and documenting, their own experiences within a 20th century world.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Many of the movement's artists came from an earlier inclusion in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Even as they eschewed its principles, they did adapt many of its techniques such as a similar use of brushwork, flatness, the use of large canvas, and innovative color and composition.

- Although there were other branches of art simultaneously inspired by the 19th century philosophies of Realism, such as Social Realism and American Regionalism, Contemporary Realist painters were largely distinctive for showing both urban and rural life in a simple fashion absent of sentimentality.

- Contemporary Realism was a way to express an immediate environment, most often through a glance at the people, landscapes, geography, still lifes and interiors that informed an artist's personal existence. These first glimpses originated around life in New York, Maine and Southampton, yet they were inspirational in establishing the concept of regional centers of art for other painters working in this vein.

- The movement revitalized realism, dusted off the perception of it being a dated historical antiquation, and gave it a new momentum that has continued throughout today in various forms including Photorealism, and Neo-Expressionism.

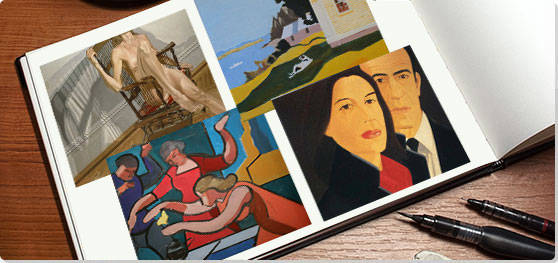

Artworks and Artists of Contemporary Realism

Early New York Evening

This painting shows a twilight view of the city from an apartment window. A green vase full of purple irises sits on the window ledge, and, beyond the balcony railing, the colors of the tenement buildings deepen in the violet light. Four smokestacks are visible on the horizon, their plumes darkening the sky. We can imagine the artist surveying the scene as she paints it from life, capturing the distinctive hues of sunset in a New York City moment, transporting the viewer to the artist's piece of the world at the time.

Freilicher was known for painting urban and country scenes in the Contemporary Realist style of documenting place from her own authentic perspective of home in both Lower Manhattan and Walter Mill, Long Island. She studied with Hans Hoffman and began as an Abstract Expressionist but was inspired by a show of Pierre Bonnard's 19th century Realist works and made the switch, taking into her new direction a love for a nostalgic color palette and the juxtaposition between domestic interiors and landscape.

Throughout her career, she painted primarily still life, usually flowers, placed in front of a window through which could be seen a cityscape or a landscape. As she said in her seventies, "I suppose I'll just keep doing what I'm doing, Even though I'm using ostensibly the same subject matter, I keep on trying to get some other kind of sensation from it. Every flower has its own cosmology, its own relationship to the foliage, to the air around it."

Freilicher preferred to call her style, "painterly realism," a term which emphasizes not only the representational nature of her work but her emphasis on the lyrical effects of color. Yet the grimy crowded buildings and the smokestacks' sooty plumes convey a realistic view that is without idealization. Porter reviewed her work in 1952, praising her artistic pursuit of "first principles," which is evident here in her sense of composition. The size of the canvas is the same dimensions as the window it portrays, and the color of the windowsill harmonizes with the color of the sky, in effect framing the top and bottom of the canvas with the violet of twilight, highlighted by the irises.

Oil on linen - Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

The Black Dress

This work portrays the artist's wife and muse, Ada, in six different poses, while on the wall to the right is partially seen a portrait of the poet, James Schuyler, who was a close friend of the couple. Ada is wearing a classic black dress and heels, reflecting the Jacqueline Kennedy style of the early 1960s.

Ada, was central to Katz's portrait practice, and became a recognizable figure in his work, furthering the Contemporary Realist signature of painting those one knows. The poet Frank O'Hara was to dub her the "First Lady of the Art World." The large scale of the canvas itself contributes to the iconic effect, as the art critic Kramer said of both Katz and Pearlstein, they "took the scale of their work from Abstract Expressionism. They wanted that big scale, but they wanted to keep that scale free for representational painting."

Katz has said that everything is about style, and his unique version can be seen here in his use of flat planes of color that create a two dimensional flatness. He also pioneered the representation of the human form as a cutout, which can also be seen in his Frank O'Hara (1959-1960), a full body portrait of the poet, cut out of wood.

Here, the sequence of different poses creates an effect like that of a classical Greek frieze, but while Ada is seen from multiple perspectives, there are only the slight variations in facial expression, primarily in the two poses on the right. The painting is so representational, that it can take a while to realize that it also departs from a purely naturalistic treatment. The figure standing behind the chair ends at the shoulders of the seated Ada, and the figures seem to be of varying heights creating an uncertainty about the space that they occupy.

Katz's individual interpretation of Contemporary Realism was toward stylization and creation of the iconic. In his billboard size portraits, the individual becomes a kind of 'sign', recognizable but reduced to essential elements, and this aspect of his work and its cool contemporaneity has had a significant influence upon other artists from the 1970s on.

Oil on linen - Brandhurst Collection, Berlin

Croquet Party

This work depicts a moment in a weekend spent with family and friends, and is illustrative of the movement's devotion toward depicting everyday domestic scenes.

Bell is depicted at the far left with his arm around his wife, the Icelandic artist Louisa Matthiasdottir, whom he met while both were studying at the Hans Hoffman School in New York. Bell's work is distinguished by fluid brushwork, planes of color, and figural dark outlines that give his representational work a dynamic effect. Each of the people depicted here is vividly present, their personalities and relationships with each other, conveyed in an astute artistic understanding of body language. Created while working from photographs, the painting retains a photographic sense of a moment caught in time. However, the work eschews photographic accuracy and detail, as the faces are not clearly seen but only suggested, and the compositional elements are simplified.

Bell, in particular, rejoiced in the simplicity of regular life and portrayed his existence and its subjects with a unique dynamism. Hints of his past as a jazz musician can be seen in the rhythmic fluidity to his work that waffles between classical, abstract, and representational.

Oil on canvas - Center for Figurative Painting, New York

Jane and Elizabeth

This painting, placed within a Long Island summer landscape, depicts a woman sitting in a deck chair while a child in red overalls playfully tries to get her attention. Porter was well known for his portraits of friends and family, each placed within the subject's world. Here, he portrays his peer Jane Freilicher outside her Water Mill home in front of the landscape that became a primary subject of her work. The child in red overalls is Elizabeth, one of Porter's children. Porter said that Freilicher and Katz were main influences on his work, but we can also see the softened hues and true sense of place so noted in earlier works by Bonnard and Vuillard.

In true Contemporary Realist form, Porter said of his work "The truest order is what you already find there...When you arrange, you fail," and, here, a sense of capturing a spontaneous moment is conveyed. The simplicity of the pictorial elements and a sophisticated color palette create this sense of immediacy. The landscape is almost abstracted to broad planes of color, the white polka dots of the overalls are echoed in two white dots on the horizon and the color of the woman's dress harmonizes with the sky. Yet it is his understanding of gestural language that makes the picture come alive.

Oil on canvas - Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill NY

Lying Female Nude on Purple Drape

This painting depicts a female nude reclining on a purple drape with her head resting on a red bolster. Characteristic of Perlstein's work, the title leaves the figure anonymous and makes the attendant props, in this case a purple drape, of equivalent importance.

Pearlstein worked as an illustrator and in the 1950s was painting Abstract Expressionist landscapes. In 1958 he began attending the studio of Merecedes Matter for figure drawing sessions, and by 1961 began painting nudes from his drawings. The following year, he adopted the Contemporary Realist dictum of painting directly from the model, as in this work.

A number of Pearlstein's works feature two or more nudes, occasionally male and female, but usually two or three women, and in later works, the props - iron cast toys, African masks, kimonos, Indian rugs - become more elaborate and contrived leaning into a more Hyperrealist mode of constructed narrative or emotion. In this earlier work though, the nude is more relaxed and sensuous. Pearlstein's study of the human body as form has spanned four decades and he's been called the preeminent figure painter of the 1960s through 2000s.

Oil on canvas - Galerie Michael Haas, Berlin

Self-Portrait in Green Window

Dodd was famous for paintings scenes from inside the vantage points of doors and windows, lending to the feeling of a viewer looking out from within or in from without. This allowed her to explore her passion for geometry and form. This work depicts a window from outside the artist's home in Maine. A single tall plant, bearing a yellow bloom, reaches up into the window where the artist, in a large yellow sunhat, and extending a paintbrush, is reflected.

Dodd has said of this work, "I was interested in the window. I saw my reflection but didn't notice the plant in front of the window until I was almost done, and considered whether I should put it in or not. I thought if I put it in, it would push the window back a bit. It gives the painting a little more space to stand."

The influence of Mondrian is reflected in this work's grid, the lines of its elements, and the contrasting primary colors of the yellow house and the blue window frame. As Dodd said, "With the window paintings, the big decision is where to put the grid...Even with plants there is a kind of geometry that helps - where are you going to situate the square, triangle or oval that underlies their growth pattern." The rectangles of the boards on the house, the framing around the window and the window itself are repeated in the larger rectangles reflected in the background behind her.

Dodd's realist subjects are often presented with a formal sophistication that becomes a meditation on space. The viewer looks into the window, then realizes that the window is looking out of the house, and that the painter must be standing in the space that viewer occupies. The sophistication of approach also lends a cool atmosphere of playful wit as the artist at work becomes a quixotic figure.

Oil on linen - Portland Museum of Art, Maine

Still Life with Rose Wall and Compote

This signature work depicts a still life with five pottery vessels and seven eggs arranged on a small table against a rose wall. A strong sense of composition is reflected in the rectangles of the table, contrasting with the curves of the eggs and the vessels, and in the color scheme that uses only soft muted colors. A kind of serene containment is conveyed as a result of this quiet composition. The viewer is invited to sit in the silence with the artist and experience a sense of timelessness.

Bailey began making representational art around 1960 when he felt, "There's so much noise in contemporary art. So much gesture. I realized it wasn't my natural bent." He began making still lifes of mostly eggs often without other objects. In 1970 his work changed to include pottery vessels when he started going to Italy. Perhaps he found inspiration in the work of artists like Giorgio Morandi who also painted simple subjects such as vases, bowls, and bottles - albeit with visible brushstrokes whereas Bailey's have none. Bailey often used the same objects repeatedly in his work, viewing them as "characters." By presenting them to us in all their plainness, he asks of us, a complicity to appreciate the subtle beauty in ordinary objects presented truthfully and without adornment.

Oil on canvas - Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC

Lower Duck Trap

Lower Duck Trap is an exceptional model of how Contemporary Realists transformed a dated movement into one that was exciting and renewed. In this piece, we see an almost illustrative rendition of an ordinary nature scene in the deep woods near Welliver's home in Maine. The light strikes the stones, water, and trees with an illuminated kiss. Each object in the frame is distinctly rendered in heavy lines and shading. The viewer dangles on the question of whether this piece is painted or a photograph, resembling the sort of filter anyone might alter a picture with today in one of many photo manipulation apps.

Welliver was known for his large landscapes, which he would traipse hours outdoors to find in just the right light. His good friend Lois Dodd had introduced him to the country and he swiftly became one with the land: rocky hills, beaver dams, tree stumps, the forests and its rushing waters, his intimate friends. He was uninterested in finding the precise color as much as he was interested in experimenting with a limited set of oil paints to concoct a hue that would "make it look like it is."

Oil on canvas - Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Icelandic Landscape with Sheep, Man and Red_Roof

This painting depicts an Icelandic landscape where, in front of the ocean with mountains in the background, a man watches two sheep. It is a typical scene from Louisa Matthiasdottir's homeland of Iceland and, though she subsequently moved to New York in 1942 to study art with Hans Hoffman, her native landscape remained a primary subject. She met and married the painter, Leland Bell, and both of them were noted realists together in the 1950s.

This piece is a great example of the way Contemporary Realist's updated from the historical Realism movement through post-war techniques. The broad areas of color in her work are dynamic, creating a sense of depth in the green of the pasture and in the blue of the water moving toward the blue of the mountains. Color also creates a kind of counterpoint, conveying vibrancy with the pure red roof of the single building, the stark light of the sun reflected off its left side wall, and the elemental forms of the sheep in black and white. The painting is simplified, conveying the isolation of the Icelandic landscape, but remarkably composed, as the various diagonals of the mound of grass, the shape of the mountains or of the outcrops create a sense of movement.

Oil on canvas - Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

Gloucester Harbor from Banner Hill

Depicting Gloucestor Harbor from Banner Hill, this work exemplifies Neil Blaine's mature landscape work. In it we find a vibrant and lively scene of the harbor with its docks and boats, the city visible in the background, and in the foreground a lush proliferation of plants and trees. The brushstrokes here create a sense of vitality, suggesting the movement of the water, and her use of color punctuates the scene, as the bright spot of a single yellow house harmonizes the yellow hull of a sailboat, and patches of yellow in the foliage and on the horizon.

Blaine became the youngest member of the American Abstract Artists group in 1944, after studying with Hans Hoffman. Subsequently she was to encounter the works of Bonnard compelling her move toward a representational style. She often created still lifes of floral arrangements or table settings. Her rhythmic brushwork reflects both the influence of Abstract Expressionism and of Bonnard and Matisse. After contracting polio, Blaine was confined to a wheelchair and turned to primarily painting landscapes that she could view from her window. This lends an extra poignancy to her place as a Contemporary Realist committed to painting the trueness of life, especially as her participation in it had become limited.

Oil on canvas - Tibor di Nagy Gallery, New York

Beginnings of Contemporary Realism

Beyond the New York School

In the 1950s, the dominant artistic movement was Abstract Expressionism, an anti-literal and anti-figuration movement that emphasized a burst of emotion, shape, and color on canvas as a visual metaphor for an artist's inner emotional state in regard to subject, circumstance or matter. The critic Russell Ferguson has written that this was the "most mythologized period in American art...the oversimplified narrative remains only too familiar: a heroic generation of Abstract Expressionist pioneers followed by a less popular "second generation," and then by the explosion of Pop Art. In that version of history, there is little room for the strong tradition of realist and figurative painting that continued throughout the period."

Never formally organized as a group or a movement, the Contemporary Realists were a close network of friendships and artistic associations surrounding the New York School, an informal group of American poets, painters, dancers, and musicians. This included Philip Pearlstein, Neil Welliver, William Bailey, Leland Bell, and Louisa Matthiasdottir, A number of Contemporary Realists, like Jack Beal, Nell Blaine, and Jane Freilicher began as noted Second Generation Abstract Expressionists, but by the mid-1950s were creating realist works. They began painting more traditional subjects like landscape, portraiture, domestic interiors, and still life, though with a contemporary awareness and technique influenced by various movements including the New York School's emphasis on capturing the everyday moment, and the color palette and line styles of their 19th-century artistic forefathers Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. The realist artists retained some elements of Abstract Expressionism, as the art historian Linda Nochlin wrote, "The largeness of scale, the constant awareness of the field-like flatness of the pictorial surface, (and) the concern with measurement, space, and interval."

At the same time, some artists like Lois Dodd, Alex Katz, and Fairfield Porter were promoting realism as art critics and educators. Porter was particularly influential as an active art critic throughout the 1950s. Furthermore, his concurrent appreciation of Abstract Expressionism and his friendships with the artists and poets of the New York School meant that his preference for realism took on intellectual credibility. He had studied at the Art Students' League with Thomas Hart Benton and had been influenced by Benton's emphasis upon the human figure, and also by the works of Vuillard and Bonnard. Porter, in effect, became a kind of artistic bridge between the earlier movements and Contemporary Realism. The most important art critic for The New York Times at the time, Hilton Kramer was also a noted proponent of the group and of individual artists associated with it.

The Many Names for the Contemporary Realists

In the early 1960s the work began to receive greater critical attention and was dubbed Contemporary Realism, collecting all of the artists working in the style beneath an umbrella term. The movement has also been called "New Realism," "Modern Realism," and "American Realism." These artists viewed themselves as stubbornly independent and often came up with their own names for their representational work. For instance, Katz preferred to call his works "post abstract," and Freilicher used the term "painterly realism." Additionally, Contemporary Realism has sometimes been included in the term "new figuration" that was coined by the French art critic Michel Ragon in 1961 for all figurative work.

Contemporary Realism and American Scene Painting

Developing after World War I and given further impetus by the Depression, American Scene painting often incorporated Social Realism, which focused on social issues and the hardships of urban America, and American Regionalism, which focused on rural America, particularly the Deep South and Midwest. Noted Social Realists were the artists Jack Levine, Jacob Lawrence, and Ben Shahn, while the best known American Regionalists were Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood. Both Social Realism and American Regionalism were critically viewed as sometimes sentimental or idealized - characteristics that were typical of much pre-WWII art. Nonetheless, into the 1950s the artist Andrew Wyeth and the illustrator Norman Rockwell continued creating Regionalist works that found a large audience.

A number of Contemporary Realists studied with Thomas Hart Benton, including Fairfield Porter and Philip Pearlstein, as did the Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock. Like the Regionalists, Contemporary Realists took on a geographical focus, creating rural artist enclaves in Maine and Southampton. However, they avoided American Regionalism's view of rural life and discarded its folk elements, preferring instead their own sophisticated contemporary techniques and cool approach. Unlike Social Realism, Contemporary Realism was usually unconcerned with social issues.

One exception to this was the work of Jack Beal. Noted in the 1950s for his boldly-colored nudes and still lifes, by the 1970s his work moved toward painting social issues, as seen in his four murals The History of Labor (1977) which he painted as a commission for the Department of Labor in Washington D.C. Reviewing the work, critic Hilton Kramer called Beal "the most important Social Realist to have emerged in American painting since the 1930s," though he went on to say "Given the generally low esteem - a disfavor bordering at times on contempt - that the Social Realist impulse has suffered in recent decades, this is not a position likely to be a cause of envy."

Contemporary Realism and the Galleries

Several New York City galleries played a significant role in promoting Contemporary Realism. Representing both Second Generation Abstract Expressionists and realist painters, the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which began in 1950, was the first to exhibit the works of Jane Freilicher and Fairfield Porter. The gallery also first published the poetry of the New York School poets John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and Frank O'Hara. As a result, it became a hub of continuing connections while promoting representational work as a noteworthy movement.

The Tanager Gallery was founded in 1952 by artists Lois Dodd, Angelo Ippolito, Charles Cajori, and Fred Mitchell. Irving Sandler, a popular art critic and historian who had been a major proponent of Abstract Expressionism, became the gallery's manager. William King, Philip Pearlstein, and Alex Katz were also members. The gallery was influential in the establishment of artist cooperative galleries throughout the city and also launched what was called "the 10th Street scene." Hilton Kramer described Contemporary Realism as not so much a school or a movement but as a group of artists who first gathered and associated with the Tanager. Ronald Bladen, Lois Dodd, Sally Hazelet Drummond, Al Held, Alex Katz, William King, Phillip Pearlstein, and George Sugarman all launched their careers at the gallery, which, Frank O'Hara wrote, could "confer on a first show by an unknown artist a distinction pretty much unavailable to the younger artist elsewhere."

The gallery also forged many long lasting relationships, including the marriage of Katz and his iconic muse Ada Del Moro. They met at a Tanager art show in October 1957; Katz has said of that meeting that Ada was "already an art-world legend," though she said she was "shy about going into galleries, " and that "The thing I do remember from when we met is that I was sitting with my hands in my lap, and this guy that I was interested in was looking at my eyes, my ears, my shoulders. The whole thing was just very sensual. And I didn't think I could handle it. But then it became just this thing that he did. I was sitting and he was painting, and that was it."

Robert Schoelkopf's gallery, which he opened in 1962 in New York City, was also devoted to showcasing contemporary figurative work and played a significant role in promoting Contemporary Realism as a viable artistic movement.

The First Regional Centers: Maine and Southampton

While New York was the central hub of Contemporary Realism, both Maine and Southampton became regional centers as well due to the large influx of artists interested in the idyllic landscape and social atmosphere found there. In 1951 Lois Dodd, William King, and Alex Katz began summering in Maine, which Dodd said, "...got us all working outdoors." They also opened the Accent Gallery in Lakewood, Maine to exhibit their own work, thus establishing a kind of central location for representative art, which attracted even more artists to the area. Subsequently, Neil Welliver moved to the state, leading to the group's being coined "the Lincolnville artists." Rackstraw Downes soon moved to Maine to study with Welliver. This migration to the country influenced the painting of landscapes and a revival of plein air painting. Welliver, for instance, would trek for miles into the woods to paint a particular landscape, like Lower Duck Trap (1978).

Fairfield Porter had family homes in Southampton and Maine, and both were a kind of breeding ground for representational artists, influencing their work in the direction of domestic interiors combined with landscape. Creating a bond with Long Island's Parrish Art Museum, Porter eventually donated over 250 works to the museum. The museum now houses the Fairfield Porter Collection, as well as many permanent collection pieces by poets and painters of the time that includes such works as Katz's Portrait of Frank O'Hara (2009). Jane Freilicher began spending her summers in Long Island as well, where she turned to creating works like Autumnal Landscape (1976-1977).

Contemporary Realism and the University

Various educational institutions played a significant role in the promotion and practice of Contemporary Realism. Neil Welliver, Alex Katz, Philip Pearlstein, and William Bailey all taught at Yale, where they influenced a number of upcoming artists. Rackstraw Downes was already a noted abstract painter while studying at Yale, who, after hearing several lectures by Fairfield Porter, was persuaded to switch to representational art. Robert Schoelkopf, who also taught at Yale, was inspired by his encounters with his Contemporary Realist peers and went on to open a New York gallery that played a great role in the revival of figurative art.

Lois Dodd taught at Brooklyn College and advocated for realist art combined with formalist sophistication, where her work had an influence on Porter. Pearlstein also, eventually, taught at Brooklyn College where his realist practice and theory influenced several generations of artists.

Contemporary Realism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The individual artists associated with Contemporary Realism continued painting in the realist manner for the rest of their careers, and some like Philip Pearlstein and Alex Katz are still active today. Accordingly, a number of separate groups and movements have been associated with Contemporary Realism. What follows is a discussion of some of the most significant and cohesively joined realist groups. Although, from the 1970's forward, the term Contemporary Realism has come to be seen in a more general sense, relating to all individual artists working in a representational style.

Contemporary Realism and The New York School

Most of the Contemporary Realists were part of a network of poets and visual artists that made up the New York School from the 1950s through the 1960s. The New York School poets Kenneth Koch, Barbara Guest, James Schuyler, Alice Notley, Frank O'Hara, and John Ashbery often drew inspiration from contemporary art movements. As a curator for the Museum of Modern Art, O'Hara was particularly influential and he, like Ashbery and Schuyler, was a noted art reviewer. Jane Freilicher played a leading role in creating connections within the New York School. Every Friday night she held gatherings, which Alex Katz described as "a fantastic education," where it seemed everyone could "play the piano, speak French and be totally brilliant in English." She was considered to be a kind of "muse" to the New York School poets as a number of them wrote works about her. In turn, she collaborated with them on a number of projects. She and Ashbery were notably great friends and after O'Hara's untimely death in 1966, she collaborated on memorial projects for the poet.

As a result of the connections between the Contemporary Realists and the New York School, representational art found a positive critical response as well as artistic encouragement and a shared influence. The New York School emphasized a witty urban style combined with a kind of stream of consciousness method that strived to capture a given moment by using vivid imagery. A number of the Contemporary Realists also focused on capturing the everyday moment and developed a style that was urbane and modern. Members of the New York School would continue to connect to other ensuing branches of the movement well into the 1980s. For instance, Ashbery, not only promoted the work of his East Coast community, but also subsequently promoted and wrote eloquently about the works of the American-born, yet English-based painter R.B. Kitaj.

The School of London

R. B. Kitaj was unallied with Contemporary Realism but was perhaps first influenced by the movement through such exhibitions as "Realism Now" and the Berlin exhibition, "Documenta 5." Both had brought international attention to realist works. Subsequently, Kitaj organized "The Human Clay," a 1976 exhibition in London that exhibited exclusively figurative paintings and drawings. In the catalogue Kitaj named the participating artists as the School of London.

The 48 artists that exhibited in the show were of varied backgrounds and connected to various movements. This included William Roberts and Richard Carline who were known for their realistic depictions of their time served in World War I. Carline painted depictions of the aerial views of bombing raids like his Baghdad 1919 that in their two-dimensional abstraction reflected a Cubist influence. Roberts was a war artist in both World Wars; his work The First German Gas Attack at Ypres (1918) depicted the horror of war in a style that reflected both Social Realism and Neue Sachlichkeit. Collin Self and Maggi Hambling, both born in the 1940s were of a later generation that showed with the group. Self's work was to become primarily associated with Pop art, and Hambling was known for her portraiture, though she also created figurative sculpture, such as her 2004 Scallop.

The show also included well-known artists who did figurative work. David Hockney had done a number of realist portraits like his Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy (1970), and Lucien Freud was also known for portraiture, as for example, The Painter's Mother II (1972). Francis Bacon, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Howard Hodgkin and Leon Kossoff also exhibited. Due to the involvement of these artists, there was a renewal of interest in figurative painting among the younger generation of artists in the 1970s and 1980s and figurative elements played a role in the development of Neo-Expressionism.

Contemporary Realism and Photorealism

The art historian Linda Nochlin co-curated, along with Mary Delahod, the figurative exhibition, "Realism Now," at Vassar College in 1968. Themed as "life of the sixties," the exhibit was meant to illustrate that, as Nochlin wrote, "it has become increasingly clear during the course of the last two years that the new realism, far from being an aberration or a throwback in contemporary art, is a major innovating impulse." Forty paintings were shown, including works by Philip Pearlstein, Jack Beal, Fairfield Porter, and Alex Katz. Also included was Alfred Leslie, who in 1962 began painting portraits in grisaille - a method of using monotone gray to emulate the look of sculpture.

The exhibition also included the Photorealist works of Ralph Goings, Malcolm Morley, and Richard Estes. Photorealism had emerged as a practice of using traditional mediums like paint and drawing to emulate the look of a photograph. As a result, a kind of blurring occurred between the two movements. Nochlin felt that the realism's "precise quality of novelty, it would seem to me, lies more in its connection with photography, with new directions in that most contemporary of all media." However, while some Contemporary Realists, like Katz, used cropping, stopgap motion, and other techniques reminiscent of film, both he and Pearlstein were outspoken in saying they had no use for the camera.

One of the best-known artists associated with Photorealism, Chuck Close, studied at Yale and became good friends with Pearlstein and Katz. However, Close did not study with them at the same time and has said, "I chafe under the term realist; the work is, I suppose, about reality, but it's also highly artificial. It's the artificiality which really interests me, the fact that it's this distribution of colored dirt on a flat surface."

That artificiality and its subject matter made Photorealism more aligned with Pop art. Photorealist subjects - storefronts, office buildings, and automobiles - were taken from contemporary Americana as can be seen in Richard Estes's Bus with Reflection of the Flatiron Building (1966-67). In contrast, domestic interiors, landscapes without figures or framed by a bouquet or a window, and scenes of family life, dominated Contemporary Realism.

While only a few Contemporary Realists, like Leland Bell, worked from photographs, most of the realists worked directly from the model or in plein air. Contemporary Realism also simplified its subject to its elements or evinced a strong sense of painterly composition, brushstrokes, and color palette. Photorealism was much informed by the technology of the camera and the photograph, and as Close said, "The camera is not aware of what it is looking at. It just gets it all down."

In the 1970s, Hyperrealism would emerge as an extension of Photorealism. What initially differentiated the two movements were the artist's intentions. Photorealist work evoked a distance between the artist and the artwork. Although Hyperrealists sought to duplicate a photo as accurately as possible, they also depicted scenes in which narrative elements or emotion came into play.

Later Developments - After Contemporary Realism

Since the 1970s the term Contemporary Realism has been used generally for artists who practice realist art with contemporary techniques. The movement's greatest influence was in creating a critical and artistic receptivity for realism as a viable continuing practice within the overall art canon. In a sense it established a foundation for artists who painted realistically to be viewed as contemporary and innovative. Many Contemporary Realists Lois Dodd, Alex Katz, and Philip Pearlstein are still active today, and their work continues to exert an influence.

At the age of 69 Rackstraw Downes was awarded a MacArthur grant for his depictions of landscapes altered by human activity, like his Presidio: In the Sand Hills Looking West with ATV Tracks & Cell Tower (2012) and his work has been connected with the 1970s New Topographic photographers (and Earth artists) like Bernd and Hilla Becher and Robert Smithson. Katz, as the Smithsonian Magazine wrote, is "cooler than ever," and his work has influenced young artists like Elizabeth Peyton, Peter Doig, and Merlin James. Pearlstein's work and his teaching at Yale and Brooklyn College have influenced the contemporary artists Janet Fish, Thomas Corey, Stephen Lorber, Charles Viera, Altoon Sultan, Tony Phillips, George Nick, and Lorraine Shemesh. Fish wrote of Pearlstein's influence, "What has stuck with me was his insistence that we take a hard and rigorous look at the world that is in front of our eyes."

Other contemporary artists are working in a realist vein, like Amy Sherald whose It Made Sense...Mostly in Her Mind (2011), is in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Dana Schutz, Jenny Saville, and John Currin are also noted contemporary realists, though their work reflects a number of influences.

With its art enclaves in Maine and the Hamptons Contemporary Realism also influenced the development of regional art centers, focused around a particular gallery or museum, often promoting realist work centered on local landscape or rural scenes. Each area has its own well-known realists; for example, Jeffrey Ripple is noted in San Francisco galleries for his precise still lifes, such as Figs (1999).

Useful Resources on Contemporary Realism

- Jane Freilicher: Painter Among PoetsBy Jennie Quilter, Jane Freilicher, and John Ashbery

- Jane Freilicher: PaintingsBy Jane Freilicher

- Catching Light: Lois DoddBy Barbara O'Brien, Lois Dodd, Alison Ferris, et al.

- Fairfield Porter: Raw: The Creative Process of an American MasterOur PickBy Klaus Ottmann

- Fairfield PorterBy John Wilmerding, Karen Wilkin, J.D. McClatchy

- Alex Katz: Revised and Expanded EditionOur PickBy Alex Katz, Carter Ratcliff, Ivana Blazwick, et al.

- Alex Katz: This Is NowBy Michael Rooks, Margaret Graham, and John Godfrey, et al.

- Nell BlaineBy Martica Sawin

- Philip Pearlstein: The Complete PaintingsBy Russell Bowman