Summary of John Marin

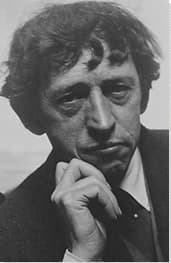

One of the first American artists to explore abstract painting, John Marin created a gestural and fractured style that captured conflicting forces of urban and natural environments through his impactful impressions of the skyscrapers and bridges of Manhattan, and the sea, sky, and mountains of New England. An acknowledged influence on the New York School, his standing as a modernist reached its highpoint in the mid-1940s when a Look magazine poll declared him: “America’s Artist No. 1.”. Although he remains perhaps best known for his watercolors, in his later career Marin showed his versatility by crossing over effortlessly into oil painting.

Accomplishments

- Widely travelled, Marin absorbed and adapted avant-garde techniques he learned from his European counterparts. Chief amongst his influences were the Post-Impressionists, Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, and the Orphist, Robert Delaunay. Their inspired use of color stimulated Marin to produce his own, distinctively American, land and cityscapes. Using the full color spectrum of watercolors, Marin effectively “reinvented” the watercolor medium as a viable means of dynamic modernist expression.

- Marin treated oils with the same zest and vigor as he did watercolors. His calligraphic and rhythmic compositions, rendered through bold impasto surface textures, fully showcased Marin’s preference for spontaneous and gestural brushwork. While he always stopped just short of the point of pure abstraction, Marin exerted a significant influence on his peers, many of whom would go on to be successful Abstract Expressionists.

- While many of Marin’s contemporaries (namely the New York School) expressed a distrustful and/or nihilistic view of their world, his outlook was eminently more flexible and optimistic. Marin’s was not a blinkered, rose-colored, view on life. But his work did demonstrate that the contemporary New York art scene could accommodate works of art that captured the light and dark of the human experience.

- While many of Marin’s drawings were finely detailed architectural images that displayed his early professional training, others were more experimental and fragmented modernist compositions. Like his paintings, Marin’s New York City drawings were produced spontaneously, capturing the towering force and human energy that he absorbed from the buildings, sidewalks and people that surrounded him.

The Life of John Marin

Critic and historian Alexander Eliot observed in his book, Three Hundred Years of American Painting (1957):"The work of many landscape painters looks as if it had been laboriously traced on a pane of glass set between the artist and the scene. Marin broke the glass and let day light and fresh air flood in ... The curving calligraphic lines following the rhythm rather than the contours of what was actually before him, re-creating the contradictory pulls and thrusts of city, sea, tide, wind, boats, tree, and mountains".

Important Art by John Marin

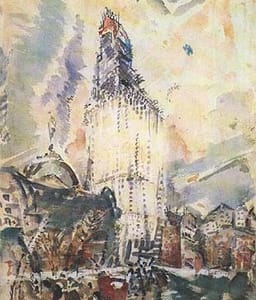

Brooklyn Bridge

Marin returned to New York in 1910 having spent five years in Europe. He became captivated by the new energy and excitement of life in the City. Art writer and collector MacKinley Helm explains that “Partly because New York had livened up during his absence and partly because it seemed fresh after Europe, Marin settled down to paint New York’s streets and rivers. Paris, he had thought, was a beautiful woman in a gray room. New York was a man, quick and dynamic, striding along in the bright, sparkling air. Marin had already sketched New York’s old buildings, old wharfs, old sailing vessels; but now he caught the city’s new motions”.

Marin produced a large number of watercolor paintings, sketches, and etchings over the next several years. These captured scenes of the city, sometimes with human figures, in a unique style that carried the influence of the Cubists and Fauvists works he discovered in Paris. While the objects in his works are recognizable (such as the Brooklyn Bridge, one of his favorite subjects), they are rendered in a semi-abstract way, with rough brushstrokes reflecting the chaotic sense of movement of the city. When human figures are present, they tend to take the form of small, silhouetted forms that appear overshadowed by the urban landscape around them. Said Marin, "The whole city is alive. Buildings, people, all are alive, and the more they move me the more I feel them to be alive". The art critic Henry McBride notes that, “the numbers of persons at that time in America capable of apprehending an artist's emotion when expressed in abstract terms was limited”, which makes the fact he received the critical and commercial success he did even more impressive.

Marin himself once wrote "Shall we consider the life of a great city as confined simply to the people and animals on its streets and in its buildings? Are the buildings themselves dead? […] I see great forces at work: great movements; the large buildings and the small buildings; the warring of the great and the small; influences of one mass on another greater or smaller mass. Feelings are aroused which give me the desire to express the reaction of these 'pull forces,' those influences which play with one another; great masses pulling smaller masses, each subject in some degree to the other's power. […] While these powers are at work pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards, I can hear the sound of their strife and there is great music being played. And so I try to express graphically what a great city is doing. Within the frames there must be a balance, a controlling of these warring, pushing, pulling forces”.

Watercolor and charcoal on paper - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Blue Sea

When Marin and his wife and son began taking summer vacations in Maine in 1914, he became enamored with the local landscapes, particularly the coastline around Cape Split (where he would eventually buy property). This area featured in a significant number of his landscapes. In The Blue Sea , a notably chaotic and abstracted watercolor, Marin presents a view of the sea as seen when looking down from the steep cliffs. Art critic Carter Ratcliff notes that around this time, Marin had begun “applying paint with a kind of torque that puts his forms at an angle to the surface and opens up the space of the image to a characteristically American feeling of limitlessness”. While Marin drew upon the abstracted styles he had encountered in Europe, he made his style his own, and made his art work for an American sensibility. Says Ratcliff, “Marin’s version of Cubism does not play off the geometry of urban architecture. It does not, in the ironic manner of Braque and Picasso, reflect on the circumscribed harmonies of traditional composition. Rather, his fragmentations of form serve his need to make contact with his subjects, to enfold them in an emphatic embrace and thus preserve them, in all their particularity, against the eroding immensities of American space”.

The layered transparent washes of blue paint work together to give the scene a sense of the turbulence, and the viewer can easily envision the water crashing against the rocks. Meanwhile, a superimposed structure of bold black lines running horizontally, diagonally, and vertically across the image further emphasize the power of the natural forces depicted. These black lines recall the sorts of lines used, for instance, in cartoons and comics to visually represent loud noises. Marin spoke throughout his life of the presence of sound as part of his visual and corporeal experience of a place, once stating “While these powers are at work, pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards, I can hear the sound of their strife and there is great music being played”. On another occasion, he stated “I demand of [my paintings] that they are related to experiences […] that they have the music of themselves”. Thus, it is conceivable that the bold black lines in The Blue Sea were a way of communicating visually the ferocious sound of the crashing swells of water.

Watercolor and charcoal on paper - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

The Pine Tree, Small Point, Maine

This, though one of his more illustrative works, is still emblematic of Marin’s signature technique of using watercolors to achieve vibrant, saturated colors. Here, he has juxtaposed bold areas of blue, yellow, and green at the center of the image, while softening and blurring the paint around the edges, imitating the way that humans experience sight, with a contrast between sharp focus at the center of our field of vision, and the vagueness of our peripheral vision. Helm writes that Marin “[hated] studios worse than the plague of mosquitoes which stung him outdoors,” and indeed, the artist often painted entire works in single sessions en plein air.

Though Marin was fascinated with, and highly adept at, representing the hustle and bustle of cities like New York, it was in the countryside that he felt most inspired. During one of his early visits to Maine, he wrote in a letter to his friend, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, “This is one fierce, relentless, cruel, beautiful, fascinating, hellish, and all the other ish’es, place”. As art dealer Meredith E. Ward explains, “his letters from Maine that summer — and every summer thereafter — were filled with a sense of wonderment for the natural beauty that surrounded him, and his sheer delight in living at the edge of the sea. […] In reading his words, it is not difficult to imagine how Marin was able to translate this passion into some of the most powerful and poetic American paintings of the twentieth century”.

Though less abstracted in form, The Pine Tree, Small Point, Maine exemplifies Marin’s less realistic, more emotion-driven, approach to color. In other words, his use of color here has less to do with a desire to represent leaves as green and water as blue (which he does) than it does with his desire to communicate emotion and convey an extra-visual experience to his viewer. Indeed, the elementary hues of green, yellow, and blue we see in this painting are, presumably, not the colors perceived by his eye. Rather, they are meant to elicit a particular emotion within us, such as joy and optimism (both of which, incidentally, were personal qualities attributed to him by friends and associates). Marin once explained “Sometimes, I like to paint a red ocean, with light red, maybe, between Venetian and Indian red, or maybe spectrum red. Red is more exciting than gray. It is not the color that makes an ocean on canvas look like a real ocean. What makes the painted ocean look real is a suggestion of the motion of water. A red ocean with motion will look more like the sea than a patch of gray paint without movement”.

Watercolor with blotting, black pencil, and charcoal on moderately thick, slightly textured, off-white wove paper (trimmed top edge) - The Art Institute of Chicago, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Valley of the Hondo, New Mexico

Marin produced this work during his second of two summers in New Mexico. He had not only been directly encouraged to visit the state by his friends, artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Rebecca Strand (wife of photographer Paul Strand), he was also inspired to visit after seeing paintings of the area produced by his friend Marsden Hartley in the 1920s. Marin’s Valley of the Hondo, New Mexico presents a sprawling landscape, with rocks, trees, cacti, and fields in the foreground, flat brown desert beyond, and mountains in the distance, beneath a grayish-blue sky. His skilled use of watercolors demonstrates his talent for representing light, weather, and atmospheric effects. For instance, small vertical strokes of this same grayish-blue paint, laying between the horizontally rendered sky and the mountains below, give the impression of isolated thunderstorms in the distance.

In typical Marin style, this painting is composed largely of rough geometric forms, and does not present a single vantage point (for instance, while the overall scene gives the viewer the sense of looking downward at the landscape, the cacti in the foreground appear as if seen head-on). Ratcliff explains that “To understand the art of John Marin we must first note the impact of Cubism [it] is clear at a glance that Marin’s mature work is crucially dependent on specifically Cubist precedents. Like the Futurist Umberto Boccioni and the Cubo-Futurist Lyubov Popova, Marin found his own uses for Cubist flattening and fragmentation. Unlike these painters and a remarkable number of others in Europe, Russia, and the United States, Marin did not invent Cubist variations in response to the quick tempo and incipient chaos of a modern, mechanized world. Nor did he refine Cubist clutter into a set of elemental forms, the building blocks of a timeless, other-worldly realm, in the manner of Piet Mondrian and his fellow geometric abstractionists. Marin painted from nature—rather, from a characteristically American feeling for nature with roots in the early years of the 19th century”.

Curator William Rudolph adds that, Marin never completely “jettisoned” what he had learned in his unhappy times at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) and the Art Students League of New York. Says Rudolph, “although when you look at Marin’s works, spatially things become more flattened and more abstract and color becomes a force in its own right, he never loses an underlying structure that […] was part of that traditional artistic training”. This painting was one of thirty watercolors of New Mexico by Marin exhibited to great critical in a 1931 show at Alfred Stieglitz’s New York gallery, An American Place.

Watercolor with black crayon, on moderately thick, moderately textured, ivory wove paper (all edges trimmed), in original frame - The Art Institute of Chicago, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

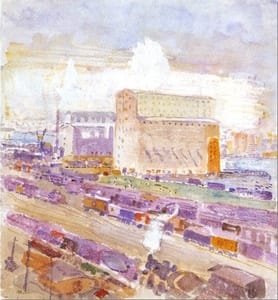

Bryant Square

Despite spending his summers in the countryside, Marin returned to New Jersey in the winter and from there regularly travelled to New York City to paint and sketch urban scenes. By the 1930s Marin was working more frequently with oils and Bryant Square sees him return once more to a location he had painted previously (in watercolor). Here he managed to capture the human bustle and energy of twentieth century urban America through soaring buildings and hectic human activity that vie for the viewers’ attention.

The Phillips Collection says of the work, “Through his handling of line, Marin creates sequences of movement that lead the eye across the image and into the canyon of skyscrapers, expressing the excitement and momentum of the streets of New York. Marin himself described them as ’buildings rearing up from the sidewalk.’ The surface of Bryant Square shows flat, thinly painted sections, almost transparent, as well as elements that are thickly painted, mainly in the lower sections of the composition. His lines equally varied; long black strokes define the major blocks within the image, while short zigzags and swift angular strokes suggest motion and the city’s quick place”.

For Marin, his rhythmic geometric forms recalled the syncopated beats of jazz music which acted as a metaphor for modern city life. American novelist and biographer E. F. Benson wrote (in 1936) that in urban scenes such as this, Marin used “within a single picture […] several compartmental episodes or closed sections, each a separate yet related unit of construction, like the phrases in a musical score”. Indeed, Marin himself wrote, “While these powers are at work, pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards, I can hear the sound of their strife and there is great music being played”. Art dealer Meredith E. Ward concludes that Marin conveys “the essence of the place as he experienced it, an experience that went beyond optical perception […] and over the next two decades produced some of the most extraordinarily ground-breaking and influential works of his career. It was these late oils that so profoundly impacted the next generation of Abstract Expressionist artists”.

Oil on canvas - The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

Tunk Mountains, Autumn, Maine

Marin executed paintings of both cityscapes and landscapes, as in his later work Tunk Mountains, Autumn, Maine, in which his application of impasto paint is thicker than in many of his other works and the image seems to want to “come off the canvas” to meet the viewer. Tunk Mountain is a mid-elevation peak located in Okanogan County which was famous for its 40-foot-high fire lookout tower. It is one of the most prominent peaks in Maine and offers spectacular natural views - which Marin visited on several occasions during the 1940s and 1950s. Marin’s painting shows an abstracted view of a green, hilly Maine landscape below, with bold splotches of pure red and yellow giving the viewer an amplified sense of the region’s autumn foliage. The gestural freedom found in this, and other Marin works, though never reaching the point of pure abstraction, had a significant influence on the Abstract Expressionists (who would go on to abandon figuration entirely).

The Wichita Art Museum (WAM) says, “Bold surface texture, combined with calligraphic line and rhythmic composition, characterize Tunk Mountains” and seems to anticipate the emergence of the New York School. Indeed, WAM writes, “In 1950, Marin was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Venice Biennale, in the company of the younger American artists Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock. It seems appropriate for Marin to have been shown with these Abstract Expressionists, since even though his work never abandoned references to nature, its gestural freedom predicted the spontaneous brushwork of the younger painters. The liberated quality of Marin’s late work suggests that painting had become almost second nature to him. ‘As for painting—I’ve given that up— ‘Marin wrote in 1943, ‘I just tie a brush to my fingers and let that old silly brush do the painting’”.

While many in the New York art scene held pessimistic, even nihilistic worldviews, Marin’s landscapes demonstrated his more positive and optimistic outlook on life. As he stated, “Shakespeare didn’t give us tragedies only; he gave us comedies as well. I’d like the modern artists to think about that—there’s room in life for both and I’d like to see them restore the balance and give us something a little cheerful. The sun is still shining and there’s a lot of color in the world. Let’s see some of it on canvas”.

Oil on canvas - The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

Biography of John Marin

Childhood

John Marin was born in Rutherford, New Jersey. When his mother passed away just nine days after his birth, his father took him to the home of his maternal grandparents, the Curreys, in Weehawken, New Jersey (directly across the Hudson River from New York City). He was raised by his grandparents, two unmarried aunts, Jenny and Leila, and his uncle, Dick. He would live with them for thirty years. During his childhood, he often spent time at his grandfather’s peach farm in Delaware. Writing in The Atlantic journal in 1947, Mackinley Helm wrote: “While Dick Currey tended stock on the Delaware farm and shot game in the woods, John Marin drew animal pictures, and from earliest childhood he had the knack of showing his feeling for motion. Years later, when he learned to use color and began to paint orchards and circuses — as well as city streets, islands, and oceans — he knew how to make everything move on paper and canvas. Trees, birds, and ships; clouds, wind, and water: all these live and move freely in the Marin paintings”.

Education and Early Training

At his father’s insistence, Marin (who had disliked school) studied architecture at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken. Having studied for a year at the Institute, he spent the next six years working in architectural offices. By 1893 he had designed six houses in Union Hill, New Jersey. When Marin was twenty-eight, however, his aunts picked up on his unhappy demeanor, and convinced his father to allow him attend art school. He duly attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia between 1899 and 1901. At PAFA he studied under American painters Thomas Pollock Anshutz, Hugh Henry Breckenridge, and William Merritt Chase, and formed a strong friendship with the modernist painter Arthur Beecher Carles. Marin then spent a year taking classes at the Art Students League of New York, which he later viewed as a waste of his time. Neither the PAFA, nor the Art Students League, included watercolor painting in their curriculum, but having become self-taught, it became Marin’s medium of choice.

Produced in his free time (not in art school) Marin won an Academy prize for his ink drawings of birds and river boats in Weehawken. The drawings conveyed a far greater sense of movement than the static figures he was expected to produce in class. Marin later recalled “There was a boy in my class who could transfer a Greek torso to paper and make it look nice and real — as real as the plaster cast that he copied. But I thought to myself. What’s it for? A man paints a boat so it looks like a boat. But what has he got? The boat doesn’t do anything. It doesn’t move in the water, it is blown by no tempest. That copy-boat might sell boats, but it cannot be art. Art must show what goes on in the world.”

In 1905, at the prompting of his aunt Jenny, Marin’s father sent his son to Paris, where he briefly studied in the atelier of painter Auguste J. Delecluse, and at the Académie Julian. Helm writes that “In Paris, after a few weeks in professional studios, Marin fell back into vagabond habits. He roamed for four years around Europe with the apparently aimless uncertainty of his long years of loafing at home. He ‘knocked out’ some etchings, […] made a few paintings, together with hundreds of sketches, in Belgium and Holland, England and Switzerland; and learned to play a slick game of billiards with American artists who lived in the Quarter. […] When the painter met his father in Venice […] Marin père was quick to inquire what the son, now close to forty, had to show for the father’s investment. An oil painting sold to the Luxembourg? A page in a French periodical? A handful of etchings? A few watercolors in an Autumn Salon? The father was shocked to learn that the son scarcely knew the names of museums and galleries”.

While in Europe, Marin came into contact with many modern artists. He became enamored with the work of Paul Cézanne, artists of the Fauvism and Cubism movements, as well as with Robert Delaunay and his Orphism movement. Most importantly, in Paris, he met American photographer Edward Steichen, who came across Marin’s watercolors at the Salon d’Automne. Steichen introduced Marin to fellow photographer and gallery director Alfred Stieglitz. Marin and Stieglitz struck up a deep friendship that would last over decades. Caricaturist Marius de Zayas, who was also “discovered” by Stieglitz, once published a cartoon of Marin playing poker with his friends in Paris, and produced a number of images of Marin, as well as double portraits of Marin and Stieglitz, with some showing the two men connected by a tether-like line between their heads. Stieglitz introduced Marin to his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, as well as artists Max Weber, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley.

Marin returned to the United States (basing himself in New York) in late 1909 but returned to Europe for a trip in the summer of 1910, during which he produced a series of impressive watercolors of the Austrian state of Tyrol. Art critic Carter Ratcliff notes that “Marin tended to underplay the importance of the time he spent abroad. […] Marin’s comments and glaring omissions [in his journal entries, which made almost no mention of his time in Europe] signal the not entirely convincing nonchalance of an American determined not to be impressed by Europe. It may well be that his indifference was a necessary pretense, a way of freeing himself to find his own uses for Cubism and other European challenges to the pictorial inheritance of the Renaissance”.

Mature Period

Stieglitz was the owner of The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue. Better known simply as, Gallery 291, it led the way in showcasing European avant-garde art in America including works by Matisse, Rodin, Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rousseau, and Picabia. Steichen suggested to Stieglitz that they show “the anti-photographic in art” alongside their “art-in-photography photographs”. He also exhibited with the painter Alfred Maurer. Helm writes that Maurer “was an academician who had lately gone ‘modern,’ while Marin’s paintings of street scenes and bridges in Paris and London were as ‘anti-photographic’ as anything Steichen had seen from American sources. Stieglitz stepped in and promised Marin enough money to live on (not without shrewdly noting that living was cheap in Weehawken) and, receiving his work in return, gave him his first one-man show at Photo-Secession in little more than a year”. Stieglitz continued to showcase Marin’s work nearly every year until his death (in 1953) and always backed his preference for watercolors (against the trend in the modern art world for oils).

![<i>Maine Coast</i> (1914). Marin said of his Maine landscapes, “Seems to me the true artist must perforce go from time to time to the elemental big forms — Sky Sea Mountain Plain […] But to express these you have to love these to be a part of these in sympathy. One doesn’t get very far without this love”.](/images20/photo/photo_marin_john_5.jpg)

Marin’s works of the early 1910s were expressionistic, vibrantly colored watercolors of New York City, and sketches of buildings that showed his skilled training as an architect and, as arts writer Erik R. Brockett notes, Marin’s “New York subjects displayed an energy and tension reflecting the extent to which he embraced modernism”. In 1912, he married Marie Hughes, and the couple moved to Cliffside, New Jersey. They had one son, John IV. In 1914, the family spent their summers in Maine (a location suggested to him by his friend and fellow artist Ernest Haskell). There, Marin became inspired by the rocky coastline, the sea, the sky, and its impressive sunsets. In 1934, he bought a small island (which he named Marin Island), a lobster boat, and a house on Maine’s Cape Split. When not painting, he enjoyed fishing for small-mouth bass, which he called “the finest sport in the world”.

Marin spent nearly every summer in Maine until his death, and also travelled frequently to New England. In the summers of 1929 and 1930, Marin visited Taos, New Mexico, where he stayed at the home of American writer and arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, and visited his friend, photographer Paul Strand. In New Mexico, Marin produced about 100 watercolors, as well as several sketches, of the mountains, shrublands, and prairies. Shown at Stieglitz’s An American Place gallery, the New Mexico watercolors were received to much acclaim.

Late Period and Death

Marin stated publicly that the New Mexico watercolors were to be his last in the medium. Marin did move into painting in oils, but, despite his earlier declaration, remained committed to watercolors throughout the rest of his career. He preferred working en plein air, without the use of preparatory sketches. A retrospective of his work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936. American painter Marsden Hartley wrote in the catalog, "You will never see watercolors like those of John Marin again so take a good look and remember”. By the 1940s he had achieved great acclaim and commercial success, but this was offset by two personal tragedies. In February 1945, Marin’s wife Marie passed away and, in 1946, his dear friend Stieglitz suffered a fatal stroke. Marin fell into a deep depression. He worked with O’Keeffe on the day-to-day running Stieglitz’s An American Place gallery, before he suffered a (non-fatal) heart attack, also in 1946.

Despite his personal travails, another Marin retrospective opened at the Institute of Modern Art in Boston in 1947. The same year, Look magazine conducted a survey of art critics and museum directors to determine America’s greatest artist. Marin won the vote. The legendary art critic Clement Greenberg wrote, “If it is not beyond all doubt that Marin is the best painter alive in America at this moment, he assuredly has to be taken into consideration when we ask who is”. In 1949, Edith Halpert established the John Marin Room at her Downtown Gallery, so his work would be on permanent public display.

Another prestigious retrospective was organized in 1949 at the M. H. De Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco and this was followed in 1950 when Marin received two honorary doctorates, one from Yale University, the other from the University of Maine. He became the first American to exhibit at the Venice Biennale, also in 1950. In May 1951, ARTnews called him the "greatest living American painter”. Despite his failing health, Marin continued to paint and to vacation in Maine until the last year of his life. Having lived a quiet and uneventful private life, Marin died, just shy of his 83rd birthday, at his home in Addison, Maine on October 2, 1953, and was buried at the Fairview Cemetery in New Jersey. His son donated his remaining works to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

After meeting the artist in 1947, art writer and collector MacKinley Helm wrote: “John Marin, the painter, is as purely American as Buffalo Bill. He is as Yankee as baked beans […] And he is as frugal and plain, in his life and his painting, as the New Jersey spinsters who raised him”. As evidence of his humility, Helm shared the story of how “Marin’s friends on Cape Split never knew he was so well off and famous as his pictures have made him until [one of the neighbors] saw a magazine piece about ‘The Place’ in 1944 and showed it around. Although they are clannish, the Down Easterners knew that they liked him. […] But they were startled to learn that he was a lion; that art editors called him America’s ‘No. 1 Old Master.’ They had always found him and his wife unpretentious. It had always seemed […] that Mr. Marin chose to be commonplace, while Mrs. Marin, unlike summer folks generally, never put on any airs.” Sadly, Marin and his work faded into obscurity shortly after his passing, due in large part to the popularity of large-scale action paintings and other abstract works. As art critic Paul Robert writes, “By 1950, ferocity was in, delicacy was out”.

The Legacy of John Marin

Although his name has fallen into obscurity in the seventy years since his death it was not for nothing that John Marin was named “America's Artist No. 1” by Look magazine in 1947. As art critic Roberta Smith recognizes, Marin was “possibly the first American artist to make abstract paintings”, and while he never abandoned figuration, his work had a marked influence on Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, as-well-as other twentieth-century abstract artists. According to artist and research Jean Ershler Schatz, “[Marin] is to America what Paul Cezanne was to France - an innovator who helped to oppose the influence of the narrative painters, the illustrators who were more interested in subject than form, in surface than substance. Marin brought to his work a combination of values which, at the turn of the century, was unique in this country: an aliveness of touch, colors that have both sparkle and solidity, and forms that are vibrant with an energy characteristic of our age”.

Working primarily in the unfashionable medium of watercolor, Marin’s move toward abstraction in his landscape paintings did not necessarily mean a move away from faithful representation of nature. In fact, it was through increased abstraction that he felt more capable of depicting visually a truly multi-sensory experience of nature, including the sounds, sensations, and energy evoked by a particular place. The New England Historical Society said of its adopted son, “Marin loved nature, country people and artists. He hated intellectuals, sophisticates, critics and scholars – the people who voted him America’s greatest artist and then quickly forgot him”.

Influences and Connections

-

![Alfred Stieglitz]() Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz -

![Georgia O'Keeffe]() Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe -

![Edward Steichen]() Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen -

![Paul Strand]() Paul Strand

Paul Strand - Arthur B. Carles

-

![Alfred Stieglitz]() Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz -

![Georgia O'Keeffe]() Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe -

![Edward Steichen]() Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen -

![Paul Strand]() Paul Strand

Paul Strand - Arthur B. Carles

Useful Resources on John Marin

- The John Marin Collection of the Colby College Museum of ArtBy Ruth E. Fine and Hugh J. Gourley

- Becoming John Marin: Modernist at WorkOur PickBy Ann Prentice Wagner

- John Marin: Modernism at MidcenturyBy Debra Bricker Balken

- John Marin's Watercolors: A Medium for ModernismBy Martha Tedeschi (Author), Kristi Dahm