Summary of Public Art

Whether a legally commissioned statue of a noted community leader in a town square or a slap dash stencil spray-painted guerrilla-style in the dark of midnight on a storefront, art frequently engages with audiences outside of galleries and museums. This art, meant for access by the world-at-large in public spaces, serves as a democratic way for an artist to express to the masses. Public Art thus becomes artwork for the populous, instigating through visuals, actions, ideas, and interventions, a participatory audience where none prior existed. While the public display of art objects is not a solely modern phenomenon, recent innovations in Public Art forms indicate critical redefinitions of concepts like community, collective identity, and social engagement.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Public Art's role serves multiple purposes, often simultaneously: to aesthetically beautify space, to educate, to commemorate important people and events, to act as a tool of political or social propaganda, to activate, to document daily life, and to represent a community's ethos.

- Public Art appears in multiple forms that can mimic or depart from more traditional presentations of art including sculptures/statues, site-specific installations, murals, architecture, graffiti, actions, interventions, land and environmental art, performance, and more. Yet its main common denominator is its potential to be experienced within a discerned democratic and free sphere, bypassing the narrow and niche audiences of institutions and galleries.

- Although Public Art's roots originated in officially sanctioned works to compel historical pride and connect communities through accessible culture, the 1970s saw an expansion of its usage as the ideas of public space as democratic canvas arose within the civil rights movements. Public Art's definition bloomed to encompass illegal Street Art, artist-initiated public interventions, urban renewal-based commissions, and personal expressions of contemporary artists beyond commercial or partisan limitations.

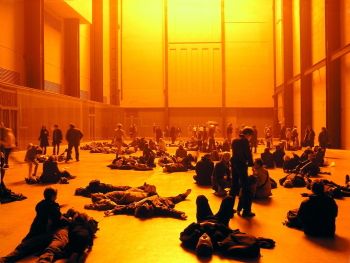

- As Public Art has evolved to not just represent but to also engage with the public sphere many contemporary pieces are being designed with the relationship between the work and its audience in mind. This relationship becomes part of the artwork's intended message, impacting both artist and viewer, laying ground for myriad possibilities in experience and interpretation. These practices inform a wide umbrella of modern artistic categories including New Genre Public Art, Relational Aesthetics, Dialogical Art, and Participatory Art.

- Critique and conflict continue to pepper the Public Art arena as the politics surrounding representation have become forefront within society. The rise of "cancel culture" has brought into question the validity and longevity of historical artworks that no longer resonate with contemporary thought just as artists tout the public space as one in which uncensored singular voices should perpetually have the right to flourish.

Artworks and Artists of Public Art

El Pueblo y sus Falsos Líderes (The People and their False Leaders)

The People and their False Leaders poses a mass of emaciated, bald, blind, and unclothed men (at the right) in opposition with a group of "leaders" (to the left), who appear plump and well fed, and are dressed in workers' overalls. While the gaunt figures are indistinguishable from one another, each of the leaders bears individualizing features. The mass of skeletal figures, with arms raised and fists clenched, attack the leaders, who recoil from the aggression. Several of the leaders hold tools and weapons (like saws and knives, symbolizing the use of force) as well as opened books, pointing to the pages (symbolizing the way that those in power use theory, recorded "history" and codified "knowledge" to strengthen and maintain their authority). Blood-red flames (which, for Orozco, symbolize energy and transformative force) lick up and outward from the attacking mass, threatening to consume the flammable books.

The work exists in the Enrique Díaz de León Auditorium of the former rectory of the University of Guadalajara, Mexico, where muralist José Clemente Orozco produced two murals during the late 1930s that deal with injustices suffered by the most vulnerable members of society, the hypocrisy of those in power, and the prevalence of violence in the country. Both murals demonstrate Orozco's Expressionist style and use of warm, bold colors. Although Orozco was well versed in theories of proportion and composition, he also believed that a true genius knows when to break those rules. Contemporary painter Roberto Rébora says, that "In Orozco a descriptive force cohabits in intimate relationship with geometry and technical drawing."

Like most Mexican Muralism, this work offers a message in alignment with Socialist ideals, highlighting the injustice of abuse of power by the ruling class wielded against the common man, and the resultant suffering of the latter. Having lived through, and fought in, the Mexican Revolution, Orozco tended to express strong emotions, violence, and torment in his works.

His decision to place this particular mural in a university auditorium was likely well-considered. Although much Mexican Muralism aimed to communicate to a largely illiterate audience, Orozco may have wished, for this commission, to communicate to the students, professors, and other intellectuals who would have attended lectures and other events in this space, that knowledge is power, and with great power comes great responsibility. In other words, the mural may have been intended as a reminder to this more literate and academically-minded audience that, as leaders in their local and national communities, they have a responsibility to ensure that their research and theories do not contribute to social injustice and the abuse of power. To this day, the auditorium continues to host academic lectures and events, and Orozco's murals speak to new generations.

Fresco - Rectory of the University of Guadalajara (Now the Art Museum of the University of Guadalajara (MUSA))

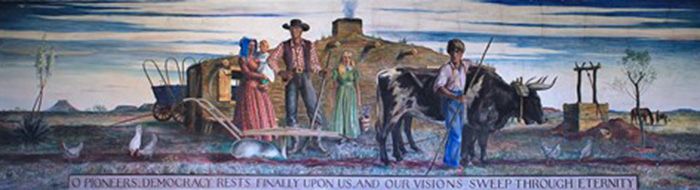

Old Pioneers

This mural, painted for the city of Big Spring's Post Office, depicts a scene of family frontier life, with a father, mother, and their children standing heroically in front of their modest home. Big Spring's Signal Mountain is visible in the background, making the mural relevant to its local audience. The family is surrounded by farming equipment and plump poultry, indicating that they are industrious people whose work ethic allows them to prosper from the land. At the bottom of the mural, Hurd included a line from a Walt Whitman poem, which reads: "O Pioneers, democracy rests finally upon us, and our visions sweep through eternity." This line reinforces the main message of the work, that the nation was built on the backs of hard-working rural Americans, who therefore deserve to be honored as heroes.

The work, painted by artist Peter Hurd, is one of the many artworks that were sponsored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Taking a cue from the Mexican Muralists, these pieces aimed to motivate and empower the American public in order to work towards progress and prosperity following the Great Depression. They presented the hard-working citizen focused on the importance of agricultural labor, and the core "American" values such as close-knit family units.

Tempera fresco - Former post office building in Big Spring, Texas (now the 118th District Courthouse)

Time Landscape

In 1965, Alan Sonfist began planning this work, which wouldn't be installed (or rather, planted) for another thirteen years. The project involved planting a variety of plant species that had been indigenous to the New York City area in pre-colonial times, on a 25 by 40 foot rectangular plot of land belonging to the Department of Transportation, at the corner of La Guardia Place and West Houston Street in Manhattan. Sonfist explained, "As in war monuments that record the life and death of soldiers, the life and death of natural phenomena such as rivers, springs, and natural outcroppings need to be remembered."

As in many of his Land Art projects, Sonfist began Time Landscape by undertaking extensive research on New York's regional botany, geology, and history, and he designed the artwork to grow and evolve naturally, making Mother Nature a co-collaborator in his work.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation explains, "When it was first planted, Time Landscape portrayed the three stages of forest growth from grasses to saplings to grown trees. The southern part of the plot represented the youngest stage and now has birch trees and beaked hazelnut shrubs, with a layer of wildflowers beneath. The center features a small grove of beech trees (grown from saplings transplanted from Sonfist's favorite childhood park in the Bronx) and woodland with red cedar, black cherry, and witch hazel above groundcover of mugwort, Virginia creeper, aster, pokeweed, and milkweed. The northern area is mature woodland dominated by oaks, with scattered white ash and American elm trees. Among the numerous other species in this miniforest are oak, sassafras, sweetgum, and tulip trees, arrowwood and dogwood shrubs, bindweed and catbrier vines, and violets."

Curator Todd Alden says of the work, "Neither a park nor a wilderness preserve, Sonfist's unusual hybrid combining both backward and forward-looking registrations radically re-conceived not only the idea of what a public monument might be (as a means of historical commemoration), but it also proposed nothing less than a re-formulated possibility frontier for art itself, including also man's historical (and future) relationship to nature."

Moving into the second half of the twentieth century, many artists began to focus on the contemporary dilemmas associated with environmental destruction, a problem that was increasingly being seen as having potential to affect the global population. In response to growing ecological concerns, land artists opted to create site-specific works that would not only highlight the threat of these issues, but that also employed carefully selected sites and natural (often living) materials as opposed to merely installing unnatural man-made constructions into public spaces. Many of these artists, like Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria, and Robert Smithson tended to execute Land Art projects in remote locations like deserts and dried-up lakes.

On the other hand, Sonfist chose to bring Land Art to densely populated urban environments, highlighting the importance of preserving nature within city centers. He explains, "My feeling is that if we are going to live within a city, we have to create an understanding of the land. And that includes suburban dwellers as well. We have to come to a better understanding of who we are and how we exist on the planet."

Earth, indigenous trees, bushes and flowers - Greenwich Village, New York City

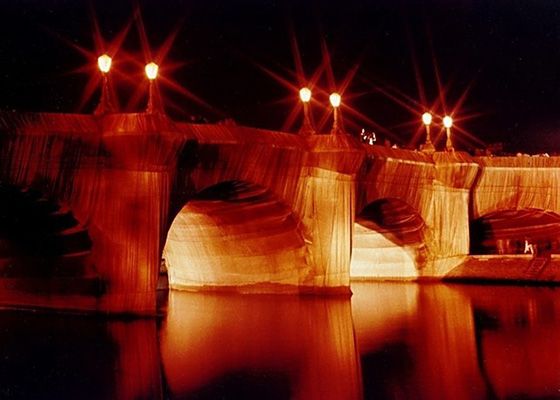

The Pont Neuf Wrapped

For the Point Neuf project, married couple Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (born in Bulgaria) and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (born in Morocco to French parents) enveloped Paris' oldest bridge in 430,000 square feet of sand-colored polyamide fabric. After a full decade of planning, the work of wrapping the bridge began on August 25, 1985 and was finished on September 22. Over three million viewers saw the work before it was removed on October 5.

This work serves as an example of New Genre Public Art, and more specifically, of Site-Specific Art, in that the project was designed for one specific location, with the aim of working with and "metamorphosing" the existing structure and surrounding urban landscape. The artists' aim was not to conceal the bridge, but to transform it into a new sculptural form, revealing and highlighting the bridge's geometry, proportions, and angles. The color chosen for the fabric was intended to blend in with the color of the sandstone streets in Paris at sunset.

Moreover, the in-person experience formed a crucial element of the work. As Christo explained, "Our work has to be experienced, lived, touched [...] People have to feel the air, see the work breathing, living, moving in the wind, changing colours every time of the day. Images, whether they are books, postcards, posters or films do not substitute. They are a souvenir, a record but they do not substitute the real experience."

Writing about New Genre Public Art, art historian, critic, and curator Arlene Raven notes that "Often these works are temporary, leaving traces in the hearts and minds of all those affected by the process rather than merely leaving monuments in their midst." Similarly, curator and art historian Miwon Kwon identifies impermanence as an important element of much site-specific art, as evidenced by Christo and Jean-Claude's aversion to creating permanent artworks. As Christo explained, when it came to their work, "If you didn't see it, you missed it."

The artist couple were famous for creating large-scale, outdoor, site-specific interventions, such as this one, from the 1960s until Jeanne-Claude's passing in 2009, frequently altering or "wrapping" pre-existing historical buildings and monuments. Christo passed away in 2020. The duo always refused sponsorship, funding their projects themselves (usually through the sales of preliminary drawings). Their projects often required the involvement of large teams of people (such as the nearly 300 workers involved in The Point Neuf Wrapped), years of planning, and extensive public outreach and collaboration with local communities and governments.

In this way, Christo and Jean Claude's work demonstrated more of a participatory ethos that intimately involved the local community, offering possibilities for urban citizens to refuse succumbing to the "blasé attitude" and the "crowd of strangers" that sociologists George Simmel and Ernest W. Burgess associated with metropolitan life, and instead forge new forms of community and discover "new possibilities of unity," as desired by Welsh Marxist theorist Raymond Williams.

Polyamide fabric, secured by rope and steel chains - Pont Neuf, Paris

Tilted Arc

One of the more controversial examples of site-specific art is Tilted Arc by American minimalist sculptor Richard Serra, comprised of a single, solid, slightly curved, slightly tilted, 120-foot-long, 12-foot-high plate of Cor-ten steel. The work was originally conceived for, and installed in, the Federal Plaza in downtown Manhattan, New York City, and was commissioned by the United States General Services Administration Art-in-Architecture program.

The sculpture boldly bisected the plaza, and Serra's intent was for "The viewer [to become] aware of himself and of his movement through the plaza. As he moves, the sculpture changes. [...] Step by step, the perception not only of the sculpture but of the entire environment changes." However, local office workers viewed the work as an eyesore and an obstruction, as a "graffiti catcher" and an "iron curtain." An employee of the nearby U.S. Department of Education remarked that, "It has dampened our spirits every day. It has turned into a hulk of rusty steel and clearly, at least to us, it doesn't have any appeal [...] and for those of us at the plaza I would like to say, please do us a favor and take it away."

Eventually, the displeased locals officially petitioned to have the sculpture removed. Serra responded by suing the government for thirty million dollars, saying that it had "deliberately induced" public hostility toward his work, and that removal of the work constituted a breach of contract and a violation of his constitutional rights (as it would negatively impact his sales and commissions as well as his artistic reputation). Serra argued that "To move the work is to destroy the work," and, as professor of Performance Studies Nick Kaye notes, this simple phrase serves as a "key definition" of site-specific art.

In the end, the Federal District Court ruled against Serra in July of 1987, and the sculpture was cut into three parts and removed from the site in March 1989. However, as intellectual property lawyer Judith A. Bresler notes, the controversy surrounding Tilted Arc likely contributed to the 1990 enactment of the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), which provides "moral rights" to the artist so that they have rights to attribution and integrity when it comes to paintings, drawings, and sculpture, although a 2006 decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals established that VARA does not protect location as a component of site-specific artwork.

Artist, art historian, and art critic Suzi Gablik writes that "What the Tilted Arc controversy forces us to consider is whether art that is centered on notions of pure freedom and radical autonomy, and subsequently inserted into the public sphere without regard for the relationship it has to other people, to the community, or any consideration except the pursuit of art, can contribute to the common good. Merely to pose the question, however, indicates that what has most distinguished aesthetic philosophy in the modern paradigm is a desire for art that is absolutely free of the pretensions of doing the world any good." As cultural theorist Malcolm Miles explains, the controversy surrounding this work "demonstrated the bankruptcy of late modernist art in terms of social relatedness."

Cor-ten Steel

Vietnam Veterans Memorial

While many Modern and Contemporary artists continue to create traditional, figurative monuments and memorials, others employ newer styles, challenging preconceived notions of the "appropriate" visual language of memorialization. For example, Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans Memorial (VVM) honors service members of the U.S. armed forces who died or went missing in action in the Vietnam War. The design for the memorial draws from Lin's experience working with Land Art. The main portion of the memorial is the Memorial Wall (or Wall of Names), comprised of two 246 foot-long polished black granite walls, which meet at a 125˚ angle, and taper vertically downward toward the two ends. The walls are engraved with nearly 60,000 names of the servicemen being honored. The walls are sunken into the earth, representing a healing wound.

Despite being the most visited of all memorials in Washington D. C., the VVM has sparked a great deal of controversy, with critics attacking the unconventionally abstracted design (which contrasts with most of the other classically-inspired figurative monuments and memorials on the National Mall), as well as what is seen as the "negative" (or at best, ambiguous) political stance on the Vietnam war suggested by the form of the VVM and the use of the color black. These criticisms have been catalyzed by the fact that Lin, a first-generation Asian-American woman, was selected to create this particular memorial.

Professor of philosophy Charles L. Griswold undertakes a more thoughtful reading of the VVM. He writes that "The list of names both ends and begins at the center of the monument, suggesting that the monument is both open and closed: open physically, at a very wide angle, like a weak 'V' for 'victory'[...]; but closed in substance - the war is over. This simultaneous openness and closure becomes all the more interesting when we realize that the VVM iconically represents a book. The pages are covered with writing, and the book is open partway through. The closure just mentioned is the closure not of the book but of a chapter in it. The openness indicates that further chapters have yet to be written, and read."

Griswold asserts that the VVM "is not a comforting memorial; it is perhaps because of this, rather than in spite of it, that it possesses remarkable therapeutic capacity." He attributes this to the particular form of ritual that many visitors to the VVM enact, explaining, "when people find on the VVM the name they've been looking for, they touch, even caress it, remembering. One sees this ritual repeated over and over. It is often followed by another, the tracing of the name on a piece of paper. The paper is then carefully folded up and taken home, and the marks of the dead left in stone thus become treasured signatures for the living." Artist Suzanne Lacy asserts that this sort of "experiential engagement" accounts "in large part for the work's success." The memorial further implicates the viewer and the surrounding area, as the highly polished black granite acts as a mirror, reflecting the living visitors to the site, as well as the Lincoln and Washington monuments further in the distance.

Griswold notes that the VVM "is a memorial to the Vietnam veterans, not the Vietnam War," and asserts that it is patriotic without being heroic, and in this way it is "apolitical" and "fundamentally interrogative; it does not take a position as to the answer."

However, it is precisely the VVM's ambiguity in content, and abstraction in form, that troubles many. In response to these criticisms, two figurative sculptural additions were later installed close to the Memorial Wall. The first of these was Frederick Hart's bronze statue The Three Servicemen that depicts three servicemen who are identifiable as European-American, African-American, and Latino-American, thereby acknowledging the ethnic diversity of those who fought. Hart's statue was meant to please those who prefer a more traditional and heroic approach to memorialization, but Lin was upset, calling the decision to install Hart's statue "a coup" which "had nothing to do with how many veterans liked or disliked my piece," and she asserted that she had not received a single critical letter from a veteran.

Black granite - National Mall, Washington DC

Domestic Violence Milk Carton

American artist Peggy Diggs became concerned with the issue of domestic abuse in the United States, and after educating herself by reading extensively about the psychology and sociology of domestic violence, and by conducting interviews with rape counselors, police officers, and women's shelter workers, she decided to raise awareness of, and potentially aid victims of, domestic violence. Diggs then met with a Rhode Island woman serving a prison sentence for murdering her abuser, and the woman suggested that creating an artistic intervention at grocery stores may allow for more victims to see it, as, according to the woman, the supermarket had been the only place that her abusive husband allowed her to go to on her own.

Diggs then created four different designs for milk cartons, and with the support of domestic violence coalitions in six states, as well as Creative Time (a nonprofit arts organization in New York City), she convinced the Tuscan Dairy Company to produce and distribute one-and-a-half million cartons with her designs throughout New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania in January and February of 1992. Each carton design featured the black silhouette of a grasping hand, the words: "When you argue at home, does it always get out of hand?" and the phone number for the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Diggs states, "I love public art. [... It] is not limited. It's not isolated. It's not elitist. It doesn't exist in a corner of the culture somewhere." Her Domestic Milk Carton project demonstrated a strong participatory approach, in that it involved extensive consultation and collaboration with a variety of community members before and during its execution. In projects such as these, the concept of experience gains importance. American philosopher John Dewey understood experience as the result of the interaction (comprising participation and communication) of an organism and its environment. Likewise, German art historian Juliane Rebentisch defines experience as "a process between subject and object that transforms both," and recognizes that "differently situated subjects might [...] experience the same work differently."

The project also exemplifies the social turn (or, as artist Suzanne Lacy puts it, the focus on social responsibility, to which aesthetic concerns become secondary) that characterizes much New Genre Public Art. In order to affect social change, Diggs centered her project upon a pressing social issue, and disseminated her artwork as part of everyday life, leading to an impact that would never have been possible were her artwork confined to a gallery or museum space. In the later part of the twentieth century, many artists began to challenge the commodity status of art by creating works that were dematerialized, participatory, dialogical, and multisensory.

1.5 million milk cartons

Voyages

Despite the increasing prevalence of immaterial and participatory public artworks in recent decades, many artists continue to create sculptural works in order to beautify public space, and to serve an educational or instructive function. Icelandic sculptor Steinunn Thorarinsdottir, who has trained in England and Italy, was commissioned by the British and Icelandic governments to design two twin sculptures titled Voyages that would reside in both the port city of Hill, England, and the fishing village of Vik, Iceland. The pair of androgynous figures stand as instructive monuments to the historical relationship between the two locations, both peering out across the sea as if viewing one another. Thorarinsdottir explains that her aim in this project was to "symbolize the bond created by more than a thousand years of sea trading between Hull and Iceland" and to memorialize those who had lost their lives at sea.

Thorarinsdottir notes that "Of all the art projects I have been involved with, [Voyages] has been by far the most special and meaningful." She explains, that throughout her artistic career, "What has inspired me the most is the environment, and people. Society. The larger picture." It is her hope that her sculptures can "connect individuals to each other and to the wider environment." The unveiling of the Voyages sculptures was a community event, for which poets Angela Leighton, Carol Rumens, Cliff Forshaw, and David Wheatley composed poems.

Thorarinsdottir's sculptures can be found in cities across the world. They all share the same androgynous, anonymous appearance, with the rough finish of their surface calling to mind the Icelandic wilderness, which may seem austere and cold to some. However, she asserts "Using human figures makes it possible for people to relate to this work very directly, but at the same time the characteristics of the figure are reserved and anonymous - they don't force themselves on the viewer." Moreover, the idea of family forms the basis of her artistic practice as Thorarinsdottir creates the molds for her sculptures using her sons' bodies. Philosophy professor Peter Osborne asserts that Thorarinsdottir's works are "magical alchemical creations that she infuses with life, humanizes and sets forth to take their place in the landscape."

Bronze - Hull, England

Cloud Gate

After winning a design competition, Indian-born British sculptor Anish Kapoor created Cloud Gate (also referred to as The Bean due to its shape) to stand as the centerpiece of AT&T Plaza at Millennium Park in Chicago, Illinois. It sits at 33 feet high, 42 feet wide, and 66 feet long, and weighs about 110 tons. The work's seamless and highly-polished stainless steel exterior gives it a weightless quality, while also conjuring a fun-house mirror quality, reflecting and distorting the image of the visitors to the park, as well as the surrounding urban environment. In this way, the work integrates itself into the city, rather than acting as a visual imposition or physical obstruction. The work lends itself to interactivity, as its reflective nature makes it a popular photo-opportunity destination, and as its arched shape invites visitors to pass underneath it.

The form of liquid mercury, as well as spirituality and Eastern theologies like Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism all informed Kapoor in making this piece. He envisioned the sculpture as a sort of gate between man and sky, reflecting the images of both in unison. Project manager Lou Cerny of MTH Industries explains that, "When the light is right, you can't see where the sculpture ends and the sky begins." Art critic Edward Lifson considers Cloud Gate to be among the greatest pieces of Public Art in the world, as it has become a popular tourist attraction and a symbol of Chicago. Its unveiling was honored by local jazz trumpeter Orbert Davis, who wrote "Fanfare for Cloud Gate" for the occasion. Not merely beautiful, this piece of Public Art inspires viewers to take a moment to remember the presence of nature all around and their unique relationship to it, even amidst the urban environment.

Stainless steel - Millennium Park, Chicago, Illinois

Pussylluminati

Montreal-based street artist MissMe creates her unsanctioned works (usually wheat paste posters and stickers) in public spaces in cities on all continents, with the aim of promoting female empowerment, challenging toxic masculinity, and supporting feminist and anti-racist activism. Many of her works use aggressive and/or graphic imagery, for instance of female genitalia, and of rage-filled women shouting obscenities, to elicit a shock response in her viewers. In other works, she creates portraits of strong women from history (often women of color), such as Helen Keller, Frida Kahlo, Maya Angelou, Billie Holiday, and Malala Yousafzai, in order to keep these minority leaders and their achievements alive in the public imagination.

Pop culture writer Johannes Stahl notes the way in which graffiti artists employ methods that mirror those of political campaigns. He points out that although graffiti is generally thought to be a spontaneous activity, any successful action involves thorough planning of both the process, and the desired effect on the viewer. MissMe's work exemplifies this (drawing on her past career in advertising), for instance, in the way that she repeatedly paints or posts her "Pussylluminati" symbol (two hands touching at the thumbs and forefingers, with the representation of a vagina in the central space) in various locations, and promotes this symbol online as representing a sort of "gang" of empowered feminists.

MissMe pushes her objectives further, by using social media platforms (primarily Instagram) to explain her political stance and the intent behind her works more in-depth, as well as to generate public discussion of the pressing socio-political issues she deals with in her art. She also manages to maintain her anonymity, wearing a mask when she appears in photographs and videos. She writes that, "The mask hides my face. But what it truly does is reveal myself. I argue that this mask frees me from my more heavy and bounding social and cultural identities."

In the case of MissMe, "the medium is the message" (to borrow a quote from Canadian communications theorist Marshall McLuhan). The illegal and public form of MissMe's art is just as, if not more, crucial than the content of the works. She explain that "one of the recurring criticisms I would get, since I've been a teenager, is that I 'take too much space,' that I'm too assertive [...] I've spent a lot of time trying to "fix" it. And so I made myself smaller, less present, less visible [...] Until I made myself so small that I nearly disappeared. [...] Now, I'm healing from all this bullshit. I see mean fake criticism for what it is: others' insecurities. [...] I take space. My space. And if you can't handle it, get the fuck out of it."

Sticker - Montreal

Beginnings of Public Art

Historical Precedents

Public Art has existed for thousands of years, across numerous cultures and societies, and has served a range of functions.

In ancient Greek and Roman culture, for example, sculpture played an important role in communication between the state and the people. Mass-produced statues of the Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar were placed in various public locations to function as propaganda, communicating particular attributes of the leader. This persistent sculptural presence brought to mind his position as a strong orator and diplomat with a pious divine nature, reaffirming his power in the minds of the citizens. These types of idealized monuments to great leaders have continued throughout later societies, as seen in sculptures of Napoleon Bonaparte and Joseph Stalin.

Wall paintings and frescoes have also been used since ancient times, appearing in cultures as far back as the Paleolithic era, as evidenced by the cave paintings at sites like Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain. Images and/or text were painted on walls in Egyptian tombs, Minoan palaces, Mayan structures, and the streets of Pompeii. The purpose of these murals included beautification, the communication of societal beliefs, and the documentation of everyday life. In the Middle Ages, religious frescos were commonly painted in churches in order to beautify the space while portraying narratives from the bible to educate illiterate and astonish churchgoers.

In some respects architecture has also long functioned as a form of Public Art, with buildings designed to communicate particular atmospheres or messages. This can be seen in religious architecture, which is always based upon symbolism. In many cultures, the circular form that composes certain rooms, or architectural features such as the dome, takes on a mystical significance, through its suggestion of the planets, sun, and moon, or eternity. The Pantheon in Rome elicits this idea. Christian and Catholic churches and cathedrals were generally based upon a cruciform plan, referencing the symbolic shape of the cross. Meanwhile, the square forms a foundation for design in many Hindu temples, as it is believed to express celestial harmony.

The Emergence of Modern Cities and the Public Sphere

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, and the resultant relocation of high numbers of people from rural areas to urban centers, the modern city took on new importance in the cultural and social spheres, and became a discerned space of existence with particular effects on the human psyche. Consequently, all Public Art located in modern cities comes into conversation with urban life and mentality.

American historian, sociologist, and philosopher Lewis Mumford wrote in 1937 that the city is "above all things, a theater [...] of social action," as well as a "social institution," "a related collection of primary groups and purposive associations," and "an aesthetic symbol of collective unity [which] fosters art and is art."

The notion of a public sphere, based upon accessibility, has become central to discourse regarding Public Art. As art historian Rosalyn Deutsche writes, "even the most ingenuous accounts of public art agree: public space is inextricably linked to democratic ideals. When, for instance, arts administrators and city officials formulate criteria for placing 'art in public places,' they routinely employ a vocabulary that invokes, albeit loosely, the tenets of both direct and representative democracy: Are the artworks for 'the people?' Do they encourage 'participation?' Do they serve their 'constituencies? [...] Do the works relinquish 'elitism?' Are they 'accessible?'"

Public Art as Pride: Community and Memory

French philosopher Maurice Halbswachs asserts that rather than functioning solely on an individual, isolated level, memory is codependent and co-constitutive, writing that, "It is in society that people normally acquire their memories. It is also in society that they recall, recognize, and localize their memories ... It is in this sense that there exists a collective memory; it is to the degree that our individual thought places itself in these frameworks and participates in this memory that it is capable of the act of recollection." This theory is exemplified by the way that many cultures create sites and rituals devoted to collective remembering, such as Christian pilgrimages, the "Day of the Dead" celebrations in Mexico, and the observance of memorial holidays like Veterans Day in the United States or Remembrance Day in Canada. Monuments and memorials thus serve as permanent, public, visual markers of memory as it occurs within the community.

For example, contemporary artist Jim Pomeroy understands Mount Rushmore as an important and mythical symbol within "an imagined American collective identity" and "American cultural consciousness." He writes that "In company with the Liberty Bell, Statue of Liberty, Capitol Dome, Astrodome, Golden Gate Bridge, Contract Bridge, Goodyear Blimp, Hoover Dam, Martin Luther King, transistors, Chevrolets, Mickey Mouse, Washingtons crossing Delawares, Coke, Neil Armstrong, polio vaccine, Lauren Bacall, football, and pantyhose, it matrices a composite - a consensus fantasy that supplies kinship, as 'Americans,' with parameters, territories, lineage castes, roles, and history in palatable natural form."

Mexican Muralism: Public Art as Educator or Instigator

In the decades following the Mexican Revolution, from about 1920 to 1950, a group of artists turned to the ancient (pre-Hispanic) medium of fresco and mural painting in order to create art in public spaces that would use visual language to reach the illiterate majority of the populace, and that would assist in strengthening national pride as the country rebuilt itself. The muralists were guided by a fundamental belief that art belongs to the public, and should not be made elitist through privatization. Three artists in particular became central figures in post-Revolution muralism in Mexico: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Although the Mexican Muralists completed several government commissions, many of them also created works autonomously, painting their personal ideals, and at times generating controversy.

Rivera had been in Europe during the Revolution, and his art combined European Modernism and Cubism to communicate utopian ideals and the social benefits of the Revolution. Orozco and Siqueiros, on the other hand, had both fought in the Revolution, and thus produced somewhat more foreboding works. Orozco's art was influenced by European Expressionism and was highly critical of oppression by the ruling class, war and the resultant suffering of man, and the potential future threat of dependence on technology. Siqueiros experimented with new techniques and materials, nearing Futurism and Neorealism in style. Of the three, he produced works that were the most radical and Communist in content, and demonstrated a strong faith in technological and industrial advances.

Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros (the "big three") formed the Labor Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors in 1922. Their manifesto asserted that "art and politics are inseparable," and the document outlined their desire: "To socialize art [and] to destroy bourgeois individualism [as well as] to create beauty which should suggest struggle and serve to arouse it."

The muralism movement spread outside of Mexico, for instance with several American artists travelling to Mexico to view murals, and with each of the "big three" artists being commissioned to execute public murals in the United States. Artist and critic Charmion von Wiegand declared in 1934 that the Mexican muralists were "a more creative influence in American painting than the modernist French masters. [...] They have brought painting back to its vital function in society."

As culture writer Anna Purna Kambhampaty explains, "Enlivened by how Mexican artists created a national identity that was inclusive of the people's fight for freedom, American artists followed suit, with an interest in telling stories about the public fight for good," as seen in works like Charles White's public mural, Five Great American Negroes (1939-1940). Kambhampaty notes that "American artists also began to leverage art to agitate for social change," such as African-American artist Hale Woodruff, who apprenticed with Rivera. Woodruff depicted a group of white men cheering at the lynching of a black man in his linocut Giddap (1935), in order to educate audiences about the plight of oppressed peoples.

The WPA: Public Art During the Great Depression

Following the Great Depression, American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the Works Progress Administration (WPA) (and the Federal Arts Project (FAP)) as part of his New Deal in order to support struggling artists through the funding of artistic projects, by providing artists with a sense of community, and by asserting art as a worthwhile vocation, rather than a mere leisure activity. Between 1934 and 1943, the WPA hired thousands of artists to create around 200,000 paintings, murals, and sculptures in municipal buildings, schools, and hospitals across the United States. The FAP continued these activities until the start of World War II, when funds and resources needed to be diverted to the war effort.

Another important aim of the FAP was to support the production of inspiring images that communicated core American values, and depicted scenes of technological progress, agricultural abundance, quaint small town life, and vibrant city living. Realistic styles (including Social Realism and Regionalism) were preferred. In this way, the FAP aimed to position the arts as an integral part of everyday public life. Artists who worked for the WPA included painters Willem de Kooning, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Stuart Davis, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky.

Many WPA artists looked south to the Mexican Muralism movement for inspiration, both in terms of technique, and how to deal with social and political subject matter in a nation recovering from devastation. American artist Jackson Pollock was heavily influenced by Orozco's murals (as evidenced by the striking similarities between Pollock's The Flame (1934-38) and Orozco's murals Prometheus (1930) and The Epic of American Civilization (1932) as well as by the time he spent at New York's Experimental Workshop, founded in 1936 by Siqueiros. The workshop was based on the philosophy that truly radical art requires the abandonment of old practices and the pioneering of completely new techniques, leading Pollock to his signature technique of creating "drip paintings." Charles Alston, one of the first African American supervisors hired by the WPA, met Diego Rivera while Rivera was painting the mural Man at the Crossroads at New York City's Rockefeller Center, and Alston later noted that he was "very much influenced" by Rivera's murals. American artist Romare Bearden asserts that African American artists were particularly drawn to the work of the Mexican muralists because of the way in which the Mexicans "used historical subjects to educate their illiterate and impoverished people on social issues."

Street Art: Public Art as Rebellion and Activism

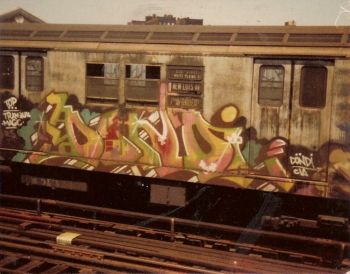

Since the mid-1900s, the term "graffiti" (whose etymological origins tie it to "scribbling" or inscribing upon a wall or surface) has come to carry strong connotations of illegality and rebellion. Contemporary graffiti emerged in the late 1960s from the black and Latino neighborhoods and street gang cultures of New York City, alongside hip hop music, break dancing, and related "street" subculture. Street culture peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, and the invention of the spray can influenced a new technique of artistic expression that soon began showing up in cities around the world. Graffiti is a subcategory of Street Art, which, in recent decades, has come to demarcate any and all unsanctioned artistic interventions in public spaces.

Curator Ethel Seno proposes that "graffiti is an outcome of psychological, intellectual, social, and political needs of a subculture, and broadly speaking, it is a symbol of the dissent by a minority faced with multiple forms of First Amendment repression." Contemporary graffiti often serves as an indicator of the conditions for inner-city communities. Brazilian street artist Deninja says, "[Graffiti is] an art that is there in the street for those that don't have a culture, don't understand art but like it for what it is... for the beggars, poor children, prostitutes, lunatics and drunks of the streets."

Although not all graffiti works feature explicit political content, Seno explains that "At its most apolitical, work done without permission in places that make others bear witness to the affront still embodies an intuitive rebellion against the assumption that the rules of property take precedence over the inherent rights of free use and self-expression."

Illegal Street Art may hold even greater potential to revive the notion of the "public sphere," in comparison to officially sanctioned "Public Art," due to a range of converging factors: accessibility, location, shock value, and anonymity.

New Genre Public Art

Since the 1960s, artists, art critics, and art historians have been operating with greater concern for art's place in the world beyond the gallery walls and have become increasingly preoccupied with the potential for art to link to the "broader social and political world," to aid in the "creative facilitation of dialogue and exchange," and to "challenge conventional perceptions [...] and systems of knowledge." Scholars refer to these Contemporary Art practices that directly take up these aims using an array of terms, including "New Genre Public Art" (Suzanne Lacy), "Relational Aesthetics" (Nicolas Bourriaud), "Dialogical Art" (Grant Kester), and "Participatory Art" (Claire Bishop). What links these practices is a focus on the relationship between artist and audience; indeed, this relationship itself (or, as Lacy puts it, "the space between artist and audience") often becomes the artwork (as opposed to a material art object). Additionally, curator Mary Jane Jacobs summarizes, New Genre Public Art "is not art for public spaces but art addressing public issues [...] It reconnects culture and society, and recognizes that art is made for audiences, not for institutions of art."

According to Lacy, New Genre Public Art describes work by artists who "have been working in a manner that resembles political and social activity but is distinguished by its aesthetic sensibility" and for whom "public strategies of engagement are an important part of [their] aesthetic language."

These practices, which encompass a range of media including installation, performance, and conceptual art, are rooted in the happenings of the 1960s and the Fluxus movement of the 1960s and 1970s (when artists challenged the conventions and authority of galleries and museums, and refused art's commodity status), and are informed by more recent discourses of Marxism, feminism, and ecology.

For her 2013 piece "Between the Door and the Street" installation, Lacy gathered 400 women and a few men-all selected to represent a cross-section of ages, backgrounds, and perspectives-onto the stoops along Park Place, a residential block in Brooklyn, where they engaged in unscripted conversations about a variety of issues related to gender politics today. Thousands of members of the public came out to wander among the groups, listen to what they were saying, and form their own opinions.

Concepts and Styles

Public Monuments and Memorials

Monuments and memorials are usually sculptural (sometimes architectural) artworks that are created for the purpose of commemorating or remembering a person, group of people, or historical event. They are often located on a site of importance, such as the site of an important battle or a tragic societal experience. They can mark unifying celebration as equally as facilitate the processing of communal grief. As Federico Bellentani, professor of semiotics and geography, explains, "monuments play an important role in the definition of a uniform national memory and identity..." Whether figurative or abstract, their form and content are always carefully designed to express a particular historical narrative.

An example of a figurative memorial is Shoes on the Danube Bank (2005) in Budapest, Hungary (by film director Can Togay and sculptor Gyula Pauer), which consists of sixty pairs of iron shoes, meant to represent the Hungarian Jews slaughtered by the Nazis during World War II. Meanwhile, architect Peter Eisenman and engineer Buro Happold chose an abstract approach in creating the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany, which is comprised of 2,711 concrete slabs or "stelae," of randomly varying heights, arranged in a grid pattern on a sloping field. According to Eisenman, the work is meant to disorient and discomfort the viewer, and to represent a "supposedly rational and ordered system" that "loses touch with human reason."

Monuments and memorials also provide opportunities for a nation to assert what kind of community they view themselves as (such as pacifist versus militarist). As Professor of philosophy Charles L. Griswold notes, "The word 'monument' derives from the Latin monere, which means not just 'to remind' but also 'to admonish,' 'warn,' 'advise,' 'instruct.'" In discussing the monuments and memorials found in the National Mall of Washington D.C. (including the Capitol Building, the Lincoln Memorial, and Washington Monument), Griswold writes that these structures "belong to a particular species of recollective architecture, a species whose symbolic and normative content is prominent. After all, war memorials by their very nature recall struggles to the death over values."

Due to their inherent political content, monuments and memorials are often controversial, particularly in places that have undergone significant political regime changes, as in the case of American monuments to Confederate heroes. Many of these Confederate monuments are seen as glorifying racist historical villains and their white supremacist ideologies, and are therefore being removed (as in the case of the Robert Edward Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia.) The World War II Memorial in Washington D. C. has also been harshly criticized, due to its lack of emotionality, and its "vainglorious" and "overbearing" focus on the glorification of national victory, with its massive granite columns and golden eagles. Architecture critic Inga Saffron criticized the monument as adopting a "pompous style [that was] also favored by Hitler and Mussolini."

Public Murals

Major muralism movements of the twentieth century, particularly post-Revolution Mexican muralism, and WPA-sponsored murals in the United States, were characterized by content that focused on developing national pride, asserting core national values, and championing technological progress in the wake of devastating events (the Mexican Revolution, and the Great Depression). These murals were not only intended to beautify public spaces, but also to communicate important messages to even the illiterate members of society. This meant that muralists often exaggerated and caricaturized their figures, and used easily recognizable symbols, to express their intended messages.

Mexican murals contained much political (usually Socialist) subject matter. As muralists were frequently commissionedin government buildings, palaces, schools, and other buildings with unique architectural features, the movement came to be characterized by allowing for compositions to be determined by the geometrical and physical particulars of a given space or surface.

Today, murals are widely used by artists, both commissioned and non-commissioned, to beautify space, remark on community, incite social change, and reflect a surrounding environment or community ethos.

Public Sculpture

When not seeking to commemorate or memorialize, public sculpture serves a range of purposes. Many artists aim merely to beautify and leave their mark on public spaces (such as Jeff Koons' Balloon Flower (Red) (1995-1999, New York City)). Others hope that their works will cause viewers to reconsider their relationship to their urban environment. For example, in Bridge Over Tree in New York's Brooklyn Bridge Park, Iranian-born, Minneapolis-based artist Siah Armajani aimed to create a sculptural installation that moved around a pre-existing tree, reminding viewers of the importance of our natural resources. Other artists create public sculptures that they want viewers to interact with, for instance, by making sculptures that can be climbed and enjoyed in phenomenological fashion.

Participatory Art

In these types of works, as curator Patricia Phillips writes, "Community involvement is the raw material of artistic practice," and the relationships amongst people are the artwork. Artist and arts writer Suzanne Lacy notes that contemporary artists working in public spaces must learn entirely new strategies: "how to collaborate, how to develop multilayered and specific audiences, how to cross over with other disciplines, how to choose sites that resonate with public meaning, and how to clarify visual and process symbolism for people who are not educated in art."

Art historian Claire Bishop states that in participatory practices "the artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations; the work of art as a finite, portable, commodifiable product is reconceived as an ongoing or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a 'viewer' or 'beholder,' is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant."

Artists engaged in participatory/dialogical/relational practice find that public spaces are generally more conducive to the aims of their projects, particularly in terms of their social objectives. According to Bishop, the "social (re)turn" in art since the 1990s indicates "a shared set of desires to overturn the traditional relationship between the art object, the artist and the audience." Bishop notes that the importance placed upon communalism over individualism is a key aspect of participatory art projects. She writes that such projects view individualism "with suspicion, not least because the commercial art system and museum programming continue to revolve around lucrative single figures." Thus it would seem, as artist and critic Suzi Gablik asserts, that participatory art aims to react against neoliberalism, pushing for increased consideration for community, communalism, and public interest rather than individualism and privatization.

Site-Specific Work

Site-specific artworks can range from sculpture, Land/Earth Art, Environmental Art, and murals/graffiti, to participatory or performance projects. What makes a work site-specific is that its physical location (as well as social considerations such as the opinions, needs, and desires of the local community) is taken into account throughout the planning and execution stages of the work. In his discussion of site-specific art, Italian art critic Bruno Corà notes the close, dynamic "rapporto inscindibile" ("inseparable relationship") between artwork and site and proposes that site-specific art cannot be moved without losing a part of its significance.

Corà notes that site-specific artists draw inspiration from each site, taking into consideration the aesthetic qualities of the space, the sounds and odors present in the space, and the particular quality of light that falls within the space. In other words, all sensory aspects of a space play into the artist's final decision about what work will be placed in a site.

Earthworks or "Land Art," describes a movement that developed mainly in the United States, influenced by Conceptualism and Minimalism, as well as the environmental movement. Earthworks are usually site-specific, and use the land and natural (often living) materials, such as rocks, soil, trees, and other plants as medium. Many earth artists, like Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer, select sites with damaged ecologies in order to suggest renewal and revitalization, and they tend to include time and the forces of nature as important considerations in their pieces, allowing for natural erosion, decay, or growth to occur and affect the work. Earth artists are also influenced by institutional critique, and by situating their works out-of-doors, within natural landscapes; they inherently challenge the dominance of museums and galleries, as well as the commodity status of art.

Street Art and Graffiti

The terms "graffiti" and "street art" are often used interchangeably, however the distinction between the two is based primarily upon aesthetic style and materials. Graffiti murals involve the use of spray paint, and are associated with a particular aesthetic, while Street art more generally refers to a range of aesthetic styles and the use of many materials including stencils, stickers, ceramic tiles, and more, with graffiti being one of its subcategories. The primary undercurrent that defines a work as Street art or graffiti, is its illegal and unsanctioned creation in public space.

Curator Ethel Seno asserts, "If we are to believe in the power of ideas, as we must, we must understand that it is not in the thoughts we keep to ourselves but only in sharing them that ideas attain their potential. This is the primary reason that public space offers such a fertile tableau for unsolicited artistic expression." The public-ness of graffiti can even elicit a participatory response on the part of the urban viewer. For instance, Ji Lee started The Bubble Project wherein he posts empty speech bubbles on top of advertisements, allowing passersby to write in their own comments, thoughts, and opinions.

Moreover, Street art can be done by anybody with the will to do it, as opposed to officially sanctioned Public Art, which usually involves certain artists who are selected or approached to do art works. There are street artists of all ages, races and ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations, and social classes, yet their voices become equal when transferred to the city walls. Furthermore, graffiti works are almost always done anonymously, with the use of a pseudonym, or 'tag,' which obscures the identity of the artist as well as their race, gender, age, etc.

Later Developments - After Public Art

A number of organizations support, commission, and fund Public Art projects in the United States and beyond. The National Endowment for the Arts (founded in 1965) recently renewed their commitment, in their 2018-2022 Strategic Plan, to "dedicate a portion of grantmaking funds to projects that integrate the arts into the fabric of community life," including permanent and temporary Public Art installations, and artist-facilitated public space design. A number of regional/state organizations operate with similar goals, such as the Public Art Fund, which was founded in 1977 with the aim of bringing Contemporary Art to the public spaces of New York City. However, with the political climate and governmental administrations constantly changing, such funds always exist with the potential for being deemed non-essential and getting cut.

Speaking of the "politics of representation," art historian and critic Rosalyn Deutsche writes that "the gallery and museum appear as the antitheses of public space," and many artists who work in public spaces share this sentiment, believing public space to offer a more open, uncensored, and accessible site of reception. In response to this criticism, more museums and galleries (such as the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh) are designating outdoor areas to include art to be seen by the public without paid entrance.

During the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 while most of the world's population were homebound, the Internet has emerged as a revolutionary new space for accessible engagement with art, as hundreds of institutions around the offered free virtual tours of their collections.

Nevertheless, Public Art continues to be the focus of criticism. For instance, art critic and curator Patricia Phillips has argued that Public Art, despite its idealistic origins, has come to do little more than merely occupy space and encourage mediocrity, and that the majority of Public Art has become overly bureaucratized (creating conflict between local communities and the general public). She notes that a common issue is that many "Public Art" projects are relegated to "negotiable" areas "that developers have 'left over' [...] after all of their available commercial and residential space has been rented or sold."

Phillips asserts that, as a result of such restrictions on where art can and should appear, many Public Art projects cater primarily to "profit-motivated market objectives" and mere beautification, rather than to a more profound interrogation of urban citizenship and space. For Phillips, a primary aim of Public Art should be to explore "the rich symbiotic topography of civic, social, and cultural forces," and, therefore, truly provocative Public Art often stands at odds with desires for such art to be inoffensive and unobtrusive. This explains the appeal of unsanctioned graffiti and Street Art interventions to artists who do not wish to be limited and censored in the act of creation.

Political theorist Chantal Mouffe asks "Can artistic practices still play a critical role in a society where the difference between art and advertising have become blurred and where artists and cultural workers have become a necessary part of capitalist production?"

Mouffe argues that public space will serve as the "battleground" of this struggle, and sees this in new "activist" art forms. This includes work that "more or less directly engages critically with political reality," like that of Barbara Kruger, Hans Haacke, and Santiago Sierra; "artworks exploring subject positions or identities defined by otherness, marginality, oppression or victimization."

Many artists also see Environmental Art as the key to the future of Public Art. American artist Patricia Johanson asserts that "Since the most critical issue in the years ahead is the preservation of life on earth, design should be approached for its ability to be life-supporting, rather than as an expression of the artist's angst, the pursuit of ideal relationships, a pilfering of art historical styles, or a quest for the new [...] Artists should have the courage to move away from work oriented to money and power and use their creativity to help solve critical problems in the 'real' world."

Useful Resources on Public Art

- My Art, My Life: An AutobiographyOur PickBy Diego Rivera and Gladys March

- Diego Rivera. The Complete MuralsOur PickBy Luis-Martín Lozano and Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera

- Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, SiqueirosOur PickBy Desmond Rochfort

- Orozco: The Life and Death of a Mexican RevolutionaryBy Raymond Caballero

- Siqueiros: Biography of a Revolutionary ArtistOur PickBy D. Anthony White

- José Clemente Orozco: An AutobiographyBy Jose Clemente Orozco

- Dialogues in Public ArtOur PickBy Tom Finkelpearl

- Critical Issues in Public Art: Content, Context, and ControversyOur PickBy Harriet Senie

- Public Art (Now): Out of Time, Out of PlaceBy Claire Doherty

- Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial LandscapeBy Kirk Savage

- Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing SocietiesOur PickBy Sanford Levinson

- Structures of Memory: Understanding Urban Change in Berlin and BeyondOur PickBy Jennifer A. Jordan

- How a Revolutionary Art Became Official Culture: Murals, Museums, and the Mexican StateOur PickBy Mary K. Coffey

- Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipOur PickBy Claire Bishop

- Art, Space and the CityOur PickBy Malcolm Miles

- Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public ArtOur PickBy Suzanne Lacy

- One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational IdentityOur PickBy Miwon Kwon

- Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974By Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon

- Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing WestBy Lucy R. Lippard

- Understanding Graffiti: Multidisciplinary Studies from Prehistory to the PresentOur PickBy Troy R Lovata and Elizabeth Olton

- Art in the StreetsOur PickBy Jeffrey Deitch

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI