Summary of Relational Aesthetics

Classical painting versus live historical re-enactment? Traditional sculpture versus staged dinner for twenty? Still life photograph versus activist advertising campaign? When French curator Nicolas Bourriaud first coined the term Relational Aesthetics in 1996, the art world already had a long history of exploring questions surrounding what constitutes art. Art had journeyed over the centuries from being, initially, a presentation of physical objects for mere beauty to a complex genre containing many modes of articulating creative concepts. At the term's inception, Relational Aesthetics essentially encompassed work that sought to produce a temporary environment or event in which viewers could participate in order to assimilate and comprehend the artist's specific impetus or message; interactivity and experience becoming more central while material, content, and form are less prioritized. Although critically this distillation remains ambiguous in its open-endedness, it does reflect an important evolution in a long lineage of art that values social encounter over product.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Works of Relational Aesthetics are typically based upon the artist's communication of his or her mission in a public, as opposed to institutional, space where the viewing population is not limited to the traditional art spectator. Thus, by expanding the works' exposure to a more far-reaching viewership, these pieces are often considered examples of temporary democracies.

- Bourriaud called relational artists and their audiences "microtopias," in that the communal bonds that are formed from these experiences create a temporary container for experiencing human connectivity within the social context of the works. Because of this, it's no surprise that much of this art evokes political conscientiousness and inspires change.

- Oftentimes, relational pieces evoke "witnessing publics," considered provocative in that they allow unrelated individuals to participate in a common feeling or event they might not otherwise experience collectively.

- An artist's subjectivity is often eschewed in the presentation of relational works. Instead, the experience itself and the people participating combine in a present time to determine the overarching tone and evoke the work's ultimate meaning.

Overview of Relational Aesthetics

Gillian Wearing's sculpture in Birmingham, UK reflects the notion that the modern definition of “real” family is something that cannot be fixed. It invites the viewer to reflect upon, and depart from the stale definition of the “nuclear” mom, dad, and two kids model, and step forward into modernity, of which we are all a part.

Artworks and Artists of Relational Aesthetics

Pad Thai

For his first solo show Pad Thai in 1992, the Argentinian-born Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija set up a kitchen inside the 303 Gallery space in New York and proceeded to cook Thai food for visitors. However, as Tiravanija explains, the "art" produced through this activity was not the food itself, but the encounters that occurred between people who participated in the communal experience. In fact, his list of materials for many of his works includes the phrase "lots of people."

Bourriaud considered Pad Thai to be revolutionary for the art world, as, rather than putting any artworks on display, Tiravanija created a situation which, in any other context, would not be considered artistic. Moreover, Bourriaud saw this participatory event, in which a sense of "microtopian" community was fostered (albeit temporarily), as a rebellion against the alienation that characterizes postmodern society.

However, Bishop argued that although Pad Thai may have produced a temporary, harmonious microtopia, "it is still predicated on the exclusion of those who hinder or prevent its realization." She also pointed out that the piece was "addressed to a community of viewing subjects with something in common," reducing its scope "to the pleasures of a private group who identify with one another as gallery-goers."

Tiravanija is the artist most commonly associated with Relational Aesthetics, and has even described his own work as "relational." He has described his work as "comparable to reaching out, removing Marcel Duchamp's urinal from its pedestal, reinstalling it back on the wall, and then, in an act of returning it to its original use, pissing in it."

In addition to Pad Thai, and a number of similar works in which he cooked food for participants, he staged other opportunities for visitors/participants to connect with one another through pop-up versions of banal activities. For example, in Untitled (1999) he constructed an exact replica of his East Village apartment and invited several students to come live in it. For his piece The Land (1999-), Tiravanija and others transformed a plot of arable land in Thailand into a communally-run site for artistic and agricultural pursuits and social collaboration, which continues today as there is no time limitation for the cultivation of it.

Performance

Turkish Jokes

For this work, Danish artist Jens Haaning made an audio recording of Turkish immigrants in Europe telling jokes in their native language. The recording was then broadcast through a loudspeaker attached to a lamppost in the Turkish area of central Oslo. In the following few years, Haaning repeated this process in various European cities with both Turkish and Arabic jokes.

The intention behind this work (in its various iterations) was to create a sense of conviviality amongst the Turkish (and later Arabic)-speaking immigrant communities in the European cities in which they now reside. Haaning explains, "One of my interests in language is based on the psychological, therapeutical effect of contacting people in a language they do not understand [...] I am also interested in the language as a power tool, because when I have been putting up works using language only understandable by minorities in the given context, the street becomes more dominated by the culture familiar with said language. Oslo became more Turkish because of the work Turkish Jokes." In other words, the immigrants' laughter upon hearing the jokes connects them in public space, while simultaneously excluding the other passers-by who do not understand.

As critic Jennifer Allen writes, "By creating communities - at once inclusive and exclusive - Haaning underscores what most art historians, theorists and critics have chosen to ignore: aesthetics is about people, not objects." Moreover, by using pure audio to create a relational experience, Haaning rejects Kantian aesthetics, which center upon visuality. At the same time, Haaning's work challenges the dominant role of museums and galleries in the art world, instead opting to bring an unexpected artistic intervention into the everyday public space of the city streets.

Loud speaker and audio recordings - Oslo

Green River Project

For the Green River Project, artist Olafur Eliasson infused a non-toxic powdered dye called Uranin into the rivers of major urban centers, including Bremen, Germany (1998); Moss, Norway (1998); Los Angeles, USA (1999); Stockholm, Sweden (2000); and Tokyo, Japan (2001). The dye caused the rivers to turn a vibrant green, appearing suddenly and without warning, and thus highlighting the interdependent and complex relationship that exists between humans and nature, the natural and artificial, and between spaces and those who dwell within them. The project was unsanctioned, created guerilla-style, and unaffiliated with any institutional organization.

As art historian Madeleine Grynsztejn explains, Eliasson's "perceiver-dependent" works emphasize "active corporeal vision" and the "kinetic involvement" of the viewer. For Eliasson, The Green River Project sought to address the way in which "a lot of people see urban space as an external image they have no connection with, not even physically" and thus the project "was really about showing people, in this city, as they walk by, that space has dimensions. A space has time. And the water flows through the city with time. The water has an ability to make the city negotiable, tangible." In other words, rivers act as an ideal site for a re-consideration of the "turbulence" that characterizes life in urban centers. Eliasson also wanted to gain insight into "how the river is perceived in the city. Is it something dynamic or static? Something real or just a representation? I wanted to make it present again, get people to notice its movement." He says, "I was interested in the reaction of the people looking at the water [...] and the way this would change their perception of the city."

Speaking about his relational oeuvre as a whole, Eliasson has stated that "...the activities or actions of [the] user in fact constitute the artwork," and, furthermore, that "art and culture [...] have proven that one can create a kind of a space which is both sensitive to individuality and to collectivity. It's very much about this causality, consequences. It's very much about the way we link thinking and doing ... And right in-between thinking and doing, I would say, there is experience. And experience is not just a kind of entertainment in a non-causal way. Experience is about responsibility. Having an experience is taking part in the world. Taking part in the world is really about sharing responsibility."

For Eliasson, de-contextualizing this work, and not allowing it to be pre-conceived of by the viewer as an art project, was crucial. In an interview with art historian, critic, and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Eliasson describes an earlier project (Proposal for a Park, 1997), which he believes "didn't work" due to the public's prior awareness of the project as an "art" project. In his view, this preconceived notion of the project as "art" leads the viewer to see the work as a painting, rather than as "some kind of modification of the urban layout." Eliasson believes that The Green River Project, at least in Stockholm, was a success in this regard, stating: "That day, when the people in Stockholm looked at the river - to them, that the water moved was a surprise. The city wasn't a postcard! Not knowing it was an artwork was important. If people knew beforehand there wouldn't be the same discussion." Indeed, the key product of this project was discussion itself, discussion through which urban citizens could share their views on what constitutes the city, and could debate and hypothesize together about what possible reasons there could be for the river to change color in this way. Eliasson's aim was to provide an engaging experience that was "infinitely variable" for individuals, yet simultaneously shared amongst members of the community.

Without institutional affiliation, The Green River Project prompted action, interaction, and engagement, rather than the passive, liminal mode of viewing which so often characterizes a museum or gallery visit. Eliasson stated, "I want the museum visitor to understand that institutional ideology and display is in itself a construction and not a higher state of truth." Eliasson believes that "the museum and exhibition scene too often makes the public passive, instead of stimulating it ... There's a reversal of subject and object [in the Green River Project]: the viewer becomes the object and the context becomes the subject. I always try to turn the viewer into what's on show, make him mobile and dynamic."

This intervention has been praised by many, yet many spectators at all locations reacted with distress or fear, likely due to the fact that the violent green hue of the river provoked "alarming associations with environmental disaster." The amount of panic that developed in some instances was so great that it led Eliasson to decide to abandon such guerilla-art installations after 2001.

Performance - Various

Workers Who Cannot Be Paid, Remunerated to Sit Inside Cardboard Boxes

In this work, which Spanish artist Santiago Sierra had previously carried out at other venues in Guatemala, Mexico, and New York, six workers who held status as political exiles from Chechenia sat inside cardboard boxes for four hours a day, over the course of six weeks. Sierra and the workers who participated hoped that the work would call attention to the plight of the exiles, who, according to German legislation, were to be given 80 marks (about $40) per month, and were prohibited from working in Germany, at risk of deportation if they were to do so. For their involvement, the workers were paid by Sierra in secret, so as not to be put at risk of deportation.

Many of Sierra's other works also involve paying marginalized people for carrying out degrading tasks, such as pushing cement blocks around a gallery floor for several hours, being tattooed, standing around at an art opening, bleaching their hair blonde, and masturbating. Sierra even gave junkies a shot of heroin in exchange for having a line shaved on their heads. Sierra justifies this exploitation by saying that "I simply follow the generally accepted rules of society. I buy human beings and pay them the wages that are customary in their respective countries." However, arts researcher Stefan Heidenreich argues "the concept of parading socially disadvantaged people in the art world as economic outcasts [...] becomes more questionable the more one sees of his work. Doubtless, Sierra's interventions get attention, but it's the kind of attention that doesn't really implement change." In response to being labeled as an "exploiter," Sierra argues that "extreme labor relations shed much more light on how the labor system actually works," and therefore his works aim to "give real visibility to these people." Yet, elsewhere he has admitted, "I can't change anything. There is no possibility that we can change anything with our artistic work."

Claire Bishop argues that it is this controversy and tension that makes Sierra's works more emblematic of "relational antagonism" than the more positive, harmonious forms of Relational Aesthetics. She writes that Sierra's works set up "'relationships' that emphasize the role of dialogue and negotiation in [his] art, but [does] so without collapsing these relationships into the work's content. The relations produced [...] are marked by sensations of unease and discomfort rather than belonging, because the work acknowledges the impossibility of a 'microtopia' and instead sustains a tension among viewers, participants, and context." She continues, "If relational aesthetics requires a unified subject as a prerequisite for community-as-togetherness, then [Sierra provides] a mode of artistic experience more adequate to the divided and incomplete subject of today. This relational antagonism would be predicated not on social harmony, but on exposing that which is repressed in sustaining the semblance of this harmony. It would thereby provide a more concrete and polemical grounds for rethinking our relationship to the world and to one other." Her dialogue exemplifies the criticism that has swirled around the Relational Aesthetics term.

Cardboard boxes - Kunstwerke, Berlin

Battle of Orgreave

For this work, British artist Jeremy Deller choreographed a reenactment of the Battle of Orgeave, a notable miner's strike that took place in the UK in 1984, during which 8,000 riot police fought with nearly 5,000 miners. 200 former miners and local residents collaborated with 800 members of over 20 historical reenactment societies, carrying out a number of rehearsals before restaging the conflict for a public audience. Deller says of the work, "Basically, I was asking the re-enactors to participate in the staging of a battle that occurred within living memory, alongside veterans of the campaign. I've always described it as digging up a corpse and giving it a proper post-mortem, or as a thousand-person crime re-enactment."

The event embodied the ethical conscientiousness, participatory/collaborative/open-ended format, and political focus of Relational Aesthetics. Yet it also highlighted some of the inherent challenges in these types of semi-scripted artworks. Deller himself referred to the project as "a recreation of something that was essentially chaos," and although participants were issued conditions of participation that were fairly strict, Deller admitted mid-performance that the event had taken on a "life of its own," over which he had very little control.

Moreover, Deller noted that bringing the middle-class battle re-enactors into direct contact with working-class miners presented its own unique set of challenges. As Bishop notes, "this also forced an uneasy convergence between those for whom the repetition of events was traumatic, and those for whom it was a stylized and sentimental invocation," as it exposed the ongoing class struggles in the area, as well as the ongoing tensions between the government and miners. She also asserts "...it is hard to reduce The Battle of Orgreave to a simple message or social function (be this therapy or counterpropaganda), because the visual and dramatic character of the event was constitutively contradictory."

The event inspired a feature-length film in 2001 by Mike Figgis, who implicated the conflict in his indictment of the Thatcher government, which had targeted the mining industry and trade unions.

Participatory performance - Orgreave, Yorkshire

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)

This work, comprised of a mountain of colorfully wrapped candies, was meant as an allegorical representation of Gonzalez-Torres's lover Ross Laycock who passed away due to AIDS-related complications. When first installed, the total weight of the pile of candy was 175 pounds, which was Laycock's ideal pre-illness body weight. Visitors were encouraged to touch, and even take, pieces of candy, and the gradual dwindling of the pile represented Laycock's decreasing weight as his illness progressed. Gonzalez-Torres stipulated that the future owner of the work had to occasionally replenish the pile, thereby granting symbolic eternal life to Laycock.

While this work may appear to be merely a sculptural installation, it depends on viewer participation (taking and consuming the candy) for meaning to be fully realized. The artist explained, "I need the public to complete my work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in." By implicating the object and the viewer in a relationship of togetherness, the artist sought to break "the pleasure of representation... the pleasure of the flawless narrative." Gonzalez-Torres thus engages in Relational Aesthetics in this work, by prioritizing use over contemplation, as well as by engaging viewers in a highly politicized experience. He explained that "the most successful of all political moves are ones that don't appear to be 'political.'" This idea is clearly exemplified by this work, in which viewers begin by engaging in the casual, pleasant activity of consuming candy, only to then become aware of the work's sobering representation of a body gradually approaching death.

Candies individually wrapped in multicolored cellophane - The Art Institute of Chicago

Beginnings of Relational Aesthetics

Precursors to Relational Art

Many canonical movements within Modern art can be seen as part of a shifting trend toward an understanding and practice of "art" that is not restricted to the production of aesthetic objects to be exhibited within institutions. These include Dadaism, Happenings, Fluxus, Situationists, and Performance, but also encompass the creation of particular situations and social encounters within our everyday milieu that focus on socio-political and social change.

Artists involved in the early 20th century Dada movement were some of the first to think about art conceptually. Rather than aiming to create visually pleasing objects, Dadaists wanted to find a way to use art to critique and challenge aspects of society such as bourgeois attitudes. Some of them like Hugo Ball and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven found that non-object-based practices such as installation and performance could be particularly useful in this regard. In the process of exploring these new artistic avenues, Dadaists also found themselves grappling with pivotal questions regarding the role of the artist and the fundamental nature of art.

American artist Allan Kaprow coined the term "happenings" in 1959 to refer to ephemeral, somewhat theatrical, but also participatory, art-related events, many of which were conceived in such a way as to be intentionally open-ended, allowing for improvisation. Artists honored this sense of spontaneity by creating rough guidelines, rather than strict rules or scripts, for participants to follow. The particular social contexts/dynamics and groups of participants (which included the audience members) involved in each happening were integral to the form the events took, causing the same performance to develop differently each time it was carried out. The central belief held by artists involved in creating Happenings was that art could be brought into the realm of everyday life.

The Situationists, a group active from 1957 to 1962, were heavily influenced by Marxist theory, which purported that while living under capitalism, individuals experience alienation and social degradation in their daily lives. They were equally informed by Guy Debord's theory of "spectacle," which states that under capitalism, the mediation of social relations occurs primarily through objects. Wanting to offer solutions toward both these concepts, Situational artists focused on creating works that brought people into direct, immediate encounters and experiences with each other. For example, they used the strategy of détournement (defined as "turning [preexisting] expressions of the capitalist system and its media culture against itself") to enact "Situationist pranks," such as distributing misinformation through false broadcasts, pamphlets, and even church sermons. Another strategy used by the Situationists was the "dérive," defined by Debord "as a mode of experimental behavior linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances." In other words, a dérive was an unplanned journey, like walking through a city's streets, during which the individual (referred to by Debord as a "psychogeographer," and also commonly understood as a sort of "flâneur" or romantic wanderer/stroller) allowed himself to be fully aware of, and engaged with, the surrounding environment. They also organized "situations" which were very similar to "happenings."

Similarly, the Fluxus group of artists, active from 1959 to 1978, sought to challenge the long-held tradition that art was to be contained within institutions and required an educated viewer. Instead, they aimed to bring art into the realm of everyday life and to make it available to the masses. Similar to the Dadaists, their art critiqued societal issues and bourgeois sentimentality. Works by Fluxus artists tended to be characterized by humor, playfulness, receptiveness to the element of chance, and audience involvement. Fluxus "events" were often shaped by a set of brief instructions (called "event scores"), which the performers, artists, and/or audiences acted out. For these artists, the artistic process mattered most, not the end product.

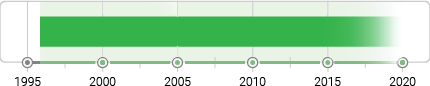

Nicolas Bourriaud

French curator and art critic Nicolas Bourriaud first used the term "relational aesthetics" in the catalogue for the 1996 exhibition Traffic, which he curated at the CAPC musée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux. Traffic included many of the artists that Bourriaud would associate with Relational Aesthetics over the next decade like Henry Bond, Vanessa Beecroft, Maurizio Cattelan, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Liam Gillick, Christine Hill, Carsten Höller, Pierre Huyghe, Miltos Manetas, Jorge Pardo, Philippe Parreno, and Rirkrit Tiravanija. For Bourriaud, the "relational art" works of these and various other artists active in the 1990s required new criteria for aesthetic judgment, as they tended to be more collaborative, participatory, and focused on the curating of social relationships and encounters than on the production of fine art. Art historian Claire Bishop, who spent much effort in quantifying and analyzing the controversial new term, noted, "It is important to emphasize, however, that Bourriaud does not regard relational aesthetics to be simply a theory of interactive art. He considers it to be a means of locating contemporary practice within the culture at large: relational art is seen as a direct response to the shift from a goods to a service-based economy."

Bishop also emphasized that Bourriaud's concept of relational aesthetics was underpinned by earlier theories. These include Walter Benjamin's Author as Producer (1934), which argued that all authors, whether they are aware of it or not, take a political stance through their selection of techniques of production; Roland Barthes's Death of the Author and Birth of the Reader (1968), which assert that an author's intentions should be irrelevant to the reader's interpretation of a work's meaning; and Althusser's Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (1969), in which Althusser describes how the ruling class dominates the working class through the use of "repressive apparatuses of the state" and "ideological apparatuses of the state;" as well as Umberto Eco's The Open Work (1962). But Bishop also argued that Bourriaud misinterpreted Eco's assertion that all works of art are potentially open to infinite readings. She explained, "Eco regarded the work of art as a reflection of the conditions of our existence in a fragmented modern culture, while Bourriaud sees the work of art producing these conditions."

Bourriaud also opted to describe relational works using many terms associated with technological culture such as user-friendliness, interactivity, and DIY (do-it-yourself). According to his book Postproduction: Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World (2002), Bourriaud described these works as developing in response to the changing mental space opened by the Internet, and as "a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space." He also used the term "postproduction" in order to refer to the way in which art's role has shifted from production toward creative, appropriative postproduction. As Professor of Visual Culture Anthony Downey explains, "relational art represents a branch of artistic practice that is largely concerned with producing and reflecting upon the interrelations between people and the extent to which such relations - or communicative acts - need to be considered as an aesthetic form."

Essentially, relational artworks seek to create an open-ended environment in which participants take part in a shared activity. Robert Stam, the head of new media and film studies at New York University, termed these shared activity groups "witnessing publics." As cultural studies scholar Anika Dačić explained, "relational aesthetics is used to describe all those artistic practices that tend to erase the line which separates spectators from the work of art [...] This social event can practically include any profane activity from our everyday lives like drinking coffee, having dinner or booking a hotel room. The whole concept depends on the artists' abilities to recreate living and real environment which we experience daily, and not to display his subjective vision of the objects and social situations." Moreover, Bourriaud identified political conscientiousness and social change as aspects of relational art, with artists and participants "learning to inhabit the world in a better way."

In 2002, Bourriaud curated the exhibition Touch: Relational Art from the 1990s to Now, at the San Francisco Art Institute, which included works by Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jens Haaning, Philippe Parreno, Gillian Wearing, and Andrea Zittel. Bourriaud described the exhibition as "an exploration of the interactive works of a new generation of artists."

In 2008, the Guggenheim Museum hosted the exhibition Theanyspacewhatever, an exhibition featuring several artists associated with Relational Aesthetics. Yet, the words Relational Aesthetics were intentionally not referenced in the show, as curator Nancy Spector did not wish to engage with the term, which was already viewed as highly problematic to many critics and scholars.

Bourriaud and other scholars/critics have since reevaluated works prior to the term's 1996 inception as engaging in its defining principles. For instance, Bourriaud noted that some earlier works involved a "degree of randomness" that served as a "machine for provoking and managing individual or collective encounters." For example, in Braco Dimitrijevic's Casual Passer-by series from the 1970s, the artist hung posters in high-traffic public spaces that featured photographic images of anonymous people he met in the streets, with the intention of misleading viewers into thinking that these individuals were somehow famous. Bourriaud also retrospectively applied the label to the work of Stephen Willats, who, since the 1960s, has been working with community members to map the social relationships that exist among them; and to the Banquets organized since the 1970s, during which artist Daniel Spoerri would carry out various sorts of social experiments, such as serving different amounts and types of food to different guests, which would produce various interesting reactions among the participants.

Concepts and Styles

Relational aesthetics has gained much criticism for its ambiguity and its elusive slippage from grasp of any specific definitions. Rather than envisioning the term as one that encompasses object-based parameters or groupings of likeness, it is more apt to locate its place in how Contemporary art addresses and implicates the viewer. The following categories represent the way relational aesthetics do just that within the artist's event or environment, and there is often conceptual overlap.

Microtopias

For Bourriaud, the most characteristic examples of Relational Aesthetics are those works that prioritize interpersonal interaction over the presentation of object removed from daily life. These artists tend to use various techniques, such as constructing spaces and situations that put people in close proximity with each other, encouraging dialogue, or creating a shared experience that fosters a sense of connectedness, lending to the creation of temporary "microtopias," in which participants develop harmonious relationships with one another.

Engagements

Many works of relational aesthetics rely on the participation of the viewer, whether by assimilation into the actual performance of the piece, or as an active participant within a constructed set of variables supplied by the artist. These works ultimately rely on audience contribution to exist, although their outcomes are as unpredictable as the human condition they strive to temporarily replicate and/or manifest.

Witnessing Publics

Many artists creating works of relational aesthetics purposefully eschew the gallery or institutional setting to show their work and the populous is an important impetus in that decision. Relying on the foundational basis of communal human experience to articulate these works, their success relies on connection to their audience. Audiences as "witnessing publics," therefore act as equal performers within the scope of the work, and the more democratic, (unconfined to a specific demographic such as "gallery goer") the better.

Installation/Gallery

Bourriaud's vision of Relational Aesthetics leans more toward works created in public. Nevertheless, many artists whose works are often characterized as "relational" choose to carry out their works inside gallery or museum spaces. These works still aim to generate interpersonal interactions that create temporary community. Although, Bishop has questioned their validity because the works' location inside of institutions limits the types of participants to only those individuals who actively choose to enter the museum or gallery space.

Later Developments - After Relational Aesthetics

It is important to note that Relational Aesthetics has been strongly criticized since it first came into usage in the 1990s, and, moreover, that the term is rarely employed even by the artists who are generally considered to be its most outstanding exemplars.

Although it was an influential term in the second half of the 1990s, applied to a wide variety of contemporary and historical pieces, Relational Aesthetics has lost some of its significance. Some suggest that its specificity has been diluted by overuse, like art dealer Gavin Brown who has asserted that the phrase has become "a catch-all for a generation of humans who are alienated from day-to-day experience." Some scholars and art educators, like Sunghee Choi, employ the term rather loosely, often using it interchangeably with "participation" in discussions of viewers' experience. Meanwhile, other critics question whether the concept really ever had much theoretical weight to begin with. For instance, art critic Roberta Smith asserts, "the claims by these artists and advocates that their work can help heal human relations and create a sense of community, any more than any other art does, are hard to prove." As Cultural Studies scholar Anika Dačić notes, "Though it's a fashionable term many scholars and art historians consider it unnecessary and argue whether it should be discarded or at least reevaluated." She continues, "These experiments in sociability do not seem to achieve the outlined goals and look more like spectacles and exhibitionism rather than radical social practice."

Bishop's main contention with Relational Aesthetics has to do with its prioritization and separation of the work's structure from its subject matter. She writes, "I am simply wondering how we decide what the 'structure' of a relational work comprises, and whether this is so detachable from the work's ostensible subject matter or permeable with its context. Bourriaud wants to equate aesthetic judgment with an ethicopolitical judgment of the relationship produced by a work of art. But how do we measure or compare these relationships? The quality of the relationships in 'relational aesthetics' are never examined or called into question."

Bishop also takes issue with the flippant and naive use of terms such as "democracy" and "social change" in Relational Aesthetics discourse, as well as the underlying assumption that "all relations that permit 'dialogue' are automatically assumed to be democratic and therefore good." In regards to the latter, Bishop asks "But what does 'democracy' really mean in this context? If relational art produces human relations, then the next logical question to ask is what types of relations are being produced, for whom, and why?" Thus, Bishop argues, the relations within Relational Aesthetics are not truly democratic, as they "rest too comfortably within an ideal of subjectivity as whole and of community as immanent togetherness," producing communities that Bourriaud himself describes as "microtopian," and involve little to no "friction."

Likewise, visual culture professor Anthony Downey explains, "Bourriaud's broad use of terms such as conviviality, democracy, dialogue and politics - in the context of contemporary aesthetics - all needs further consideration and qualification if a politics of relational aesthetics is to have purchase in a neoliberal, globalized and service-based economic milieu. And the stakes could not be higher. In a milieu where the political arena seems increasingly compromised, it would appear that aesthetics (specifically the interdisciplinarity of contemporary art practices) is being ever more called upon to provide both insight into politics itself and the stimuli for social change." In other words, scholars need to be attentive to the way in which aesthetic judgment in Contemporary Art is becoming increasingly entangled with moral judgment.

Indeed, rather than serving as a way to define a bounded artistic movement, Relational Aesthetics may be more useful as a framework through which we can think about a marked trend that has come to characterize a wide range of works and approaches to artistic practice in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Today, the strategies of relational art have come to make up part of the standard vocabulary of many contemporary artists, and the concerns of relational art (everyday life, social interaction, political critique, and social change) have become primary concerns within a wide range of contemporary artworks.

Useful Resources on Relational Aesthetics

- Olafur EliassonOur PickBy Madeleine Grynsztejn

- Tate Modern Artists: Olafur Eliasson (Modern Artists Series)By Marcella Beccaria

- Gillian Wearing (Contemporary Artists)Our PickBy Russell Ferguson

- Philippe ParrenoBy Simon Critchley, Maria Lind, Beatrix Ruf, and Hans Ulrich Obrist

- Douglas GordonBy Russell Ferguson

- Relational AestheticsOur PickBy Nicolas Bourriaud

- Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipOur PickBy Claire Bishop

- The RadicantBy Nicolas Bourriaud

- Olafur Eliasson: ExperienceBy Michelle Kuo

- Tate Modern Artists: Olafur Eliasson (Modern Artists Series)Our PickBy Marcella Beccaria

- Take Your Time: Olafur EliassonOur PickBy Madeleine Grynsztejn