Summary of Interwar Classicism

After World War I, the Great Depression and social and demographic changes taking place internationally encouraged a revival in classical artistic techniques and subject matter in Europe. Many artists, some of whom had previously worked in avant-garde styles, sought to step away from fragmentation and expressionism toward idealized bodies and calm, balanced composition. In architecture, this classical movement manifested in a turn away from decoration and toward symmetry and the grandiose. There were, across the 1920s and 1930s, a range of different rationales and approaches to Classicism in art (reaching as far back as the Greeks and Romans), ranging from xenophobia to critiques of heterosexual love. Interwar Classicism, also often known as the rappel a l'ordre (return to order), is often closely linked with the political rise of fascism in the 1930s, such that the movement was largely rejected after World War II.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Interwar Classicism is a movement that challenges the idea of modern art history as driven by progress. Instead of looking forward (and building upon the innovations of Dada, Fauvism, Cubism et al), artists turned toward the past, believing that novelty and innovation was unnecessary and inappropriate. While some artists combined elements of both classicism and modernity, the movement as a whole can be characterized as regressive and nostalgic.

- It is difficult to separate the aesthetic turn toward tradition from the politics of the interwar era. Many artists found classicism to offer security in the wake of trauma, while others imbued certain styles with moral qualities. While this occurred across the political spectrum, it was particularly pronounced on the conservative end of the spectrum, where the strength, hierarchy of values and veneration of "civilization" key to classical art and architecture resonated with the authoritarian celebration of ancient European empires.

- "Interwar Classicism" can be seen as an umbrella term that encompasses a range of different approaches. Some artists turned toward sculpting or painting idealized bodies in the style of ancient or Neoclassical art while others were influenced by the enthusiasm for simplicity whilst maintaining a machine-age aesthetic. Some artists venerated the order associated with Apollo while others embraced the Dionysian pursuit of pleasure.

Artworks and Artists of Interwar Classicism

Mother and Child

This painting shows a seated woman, clothed in a simple white tunic, holding a small child in her lap. The woman fits neatly into the rectangle of the canvas, with her crossed legs almost filling the horizontal plane while her torso, on the right of the image, occupies the bulk of the vertical plane. The child is almost at the center of the canvas, reaching up toward his mother's face; she gazes down at him, supporting his body with her left hand. The background consists of three strips, suggesting a horizon seen across a sea, and the palette of the painting is muted, composed of greys, whites, blues, beiges and browns. The figures both have calm expressions and the colors contribute to the painting's overall sense of serenity.

Pablo Picasso's interest in reviving classical art came after his 1917 visit to Rome, where he was impressed by religious imagery and early Renaissance colors. This is one of a number of paintings that show a mother and child produced by Picasso during the years that followed the birth of his own son, Paolo, in 1921. The classicism of these images is particularly evident when compared to the painter's pre-war work, in which figures are fragmented or hollow, rendered with harsh lines and discordant colors where Mother and Child features naturalistic curves and soft flesh tones. The subject matter, the landscape, the tunic of the mother and the simple title of the piece position the two figures as archetypes, placed at an idealistic remove to the modern world.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

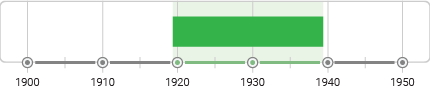

Self Portrait

Self Portrait provides two different representations of Giorgio de Chirico; the horizontal plane of the canvas is divided into two, with a plaster bust of de Chirico occupying the left foreground of the image while the person of de Chirico looks out at the viewer from the right side of the painting. The division of the painting into two sections is reinforced by the background, with a strictly ordered and geometric building receding from the center, where it protrudes upward, creating a line that frames the figures to either side. These figures are further framed by dark curtains that reach from the top of this center line to the edges, creating triangles. The plaster bust is displayed in profile, as if looking directly at the artist; it is realistic in its modelling and the lack of color is underscored by a lemon with leaves placed before it on a narrow shelf at the base of the image. The representation of de Chirico on the right similarly aims toward realism, rather than abstraction, with subtle tonal and color shifts used to reinforce the sense of the figure's presence. The artist's face is supported with his right hand; his hair is combed backward and he is wearing a white shirt, red jersey and black jacket.

De Chirico played a central role in the classical revival, publishing an article entitled 'The Return to Craft' in 1919 which was influential in both Italy and Germany. In the article, de Chirico contended that artists found themselves in a "state of confusion, ignorance and overwhelming stupidity." In searching for a solution to this, de Chirico drew not only upon classical traditions, but also on Renaissance artistic considerations, such as the relationship between painting, sculpture and life itself. Self Portrait uses the contrast between the classical bust and the lifelike figure of the artist as a means of indicating art's ability to surpass the fleeting, serving as a demonstration of de Chirico's belief that painters must look to classical sculpture as a model so as to leave the messiness of humanity behind in favour of an ideal. The juxtaposition of the bust and the artist himself both emphasizes the contrast between the permanence of art and the fleeting nature of life and - through the realism of the figure on the right - makes a convincing argument for the strength of painting as the ideal artistic mode, one in which form and color can come together. This contention, too, is indicative of Interwar Classicism, prioritizing an artistic question from the Renaissance, that of competition between the two arts, over contemporary social or political questions.

Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

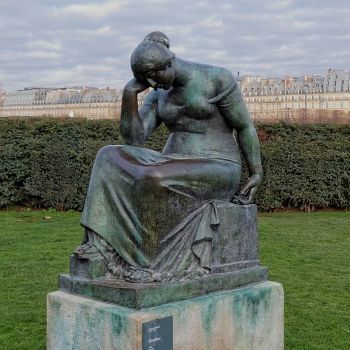

Mediterranean

This sculpture, in white marble, shows a woman alone and seated, her head bowed as if lost in thought. Her left knee is folded upward from the plain slab, doubling as plinth, on which she sits, while the other leg folds horizontally, with the foot tucked behind the ankle. The woman supports her body with her right arm, while the left arm rests on her knee, elbow bending back so that her hand rests behind her ear, creating a triangle that echoes that of the leg. She is solid in build and supported by the arrangement of her limbs, prompting a feeling of security in the viewer. The woman conforms to the ideal type of the period, with smooth skin and defined hips and breasts; she is far removed from the garçonne, or 'new woman,' that captured the attention of the avant-garde and troubled conservative ideas of gender during this decade.

Unlike many other prominent artists associated with Interwar Classicism, Aristide Maillol had been working in this style since the beginning of the twentieth century; a plaster version of Mediterranean had, in fact, been exhibited in 1905 under the title Woman. The primacy of Maillol's work is, perhaps, a reason why the "return to order" often synonymous with Interwar Classicism is sometimes dated to 1900 in sculpture. This copy in marble was commissioned by the French State in 1923, indicating the increased popularity and political cooption of the aesthetic in this period. The decision to entitle the piece Mediterranean is indicative of fashions and of Maillol's concerns early in the interwar period; he commented that the Mediterranean spirit, which he and others linked with the Greco-Roman region and antiquity, was "young, luminous and noble," like the figure in marble.

Marble - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

War (La Guerre)

The War, Marcel Gromaire's best-known painting, shows five soldiers in uniform, their faces almost swallowed by their heavy grey helmets and high-collared coats. Three men sit, as if waiting, in a row that recedes from the left foreground, where the closest man's hands are clasped on his lap, into the right middle-ground, where the third falls into shadow; behind the last of these soldiers emerge two other soldiers, moving from the right edge of the canvas. In the background is the brown dirt of the trench and a glimpse of sky above. The painting is dark, with the half-light suggesting the men are waiting in the early morning. The scene is stylized, with facial features rendered indistinctly, downplaying the individuality of each soldier, and repeating geometric shapes emphasizing their likeness.

Gromaire's painting is modern in style, making use of abstraction and fragmentation, but borrows from classical attitudes toward war, portraying the soldier not as an individual but as a type and imbuing that type with nobility. Those who chose to depict war during the 1920s often had personal experience of it, as was the case for Gromaire, who was injured at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and these shaped their depictions. While some others chose to focus on the horrors of war, creating realistic and gruesome images that made it difficult for audiences to romanticize violence, Gromaire cast his experiences in a more ambiguous light. The stillness of the figures emphasizes the dignity of the soldiers while their metal helmets, which establish the setting as modern, signal strength and durability. This portrayal of war aligns itself with classical perspectives of soldiers, sacrificing individuality for an abstract cause, as possessing a timeless beauty.

Museum of Modern Art, Paris

Seated Girl from the Back

This painting shows a woman seated in a chair, looking away from the viewer and toward a group of plain buildings with white external walls and small windows. In the background, on the left side of the canvas, is a hill where town gives way to countryside. The figure has long hair, brown and curly, tied at the nape of her neck, and wears a loose white dress with pale stripes that is slipping from her right shoulder. The viewer is unable to see the figure's face, instead encouraged to follow the apparent direction of her gaze toward the white buildings in the middle-ground. The palette is composed of natural, earthy tones, with white, beige, brown, and red dominating; there are very few bright colors.

Seated Girl from the Back encourages a nostalgic mood in the viewer through the use of such colors, associated with the classical Mediterranean, and through the stillness of the image; the dress slipping from the shoulder conveys a sense that the woman is relaxed and at ease, neither too warm nor too cold, while the neat arrangement of her hair suggests reason and balance. The plain walls of the buildings at which the figure gazes provide a space in which the viewer's own thoughts can peacefully roam and the eyes can rest. This painting, particularly when compared to the unsettling and visually surprising compositions for which Dali is best-known, reflects the use of classical tradition as a means of providing tranquility and respite in a time of widespread anxiety and rapid change.

Oil on canvas - Centro de Art Reina Sofia, Madrid

Woman Holding a Vase

This stylized portrait of a woman, shown against a plain grey backdrop, is striking for its bold colors and flat, graphic forms. The woman appears expressionless, though her eyes are fixed forward, looking at, through or above the viewer without appearing to address them in any way. The woman's top is blue, with a yellow collar, while the vase that she carries beneath her left arm is bright red, attracting the attention to the upper two-thirds of the image; the vertical lines of the grey skirt similarly guide the eyes toward the upper body. The left side of the vase is, in Léger's representation, neatly sliced off, creating the impression that the vase is completing the torso of the woman and emphasizing the connection between the pair.

The theme of a woman with a vessel is classical and Léger pays reference to this through the structure of the vase, which resembles a Tuscan or simplified Doric column, with the capital close to the woman's head, the shaft alongside her torso and the base at her waist. This echo between the body and the object carried operates as a play on the supposed similarities between women and vases, emphasized by interwar artists influenced by Freud, but also emphasizes the solidity of the figure, aligning her with an architectural tradition (signified by the column) with longevity and a material (marble) known for both strength and grace. All the while Léger is also presenting her as having the physical power to lift and carry an object as large as a toddler.

Oil on canvas - Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York

Berlin Coal Carrier

Berlin Coal Carrier shows a man emerging from a dark cellar, stepping upward, through two open doors, and toward the camera, framed by the bricks at the edge of the doorway. He has a wicker basket slung over his left shoulder and his clothes appear worn but sturdy. The darkness of the cellar beyond, in which no details can be discerned, contrasts abruptly with the sunlight into which the man is stepping. This man, identified as a coal carrier by the photograph's title, was one of many portraits composing August Sander's People of the Twentieth Century project, begun in 1922 and ended by the Nazi Party's destruction of much of his work in the 1930s; Sander protected his work by hiding negatives, retrieving and reprinting these after World War II.

August Sander's work illustrates the ways in which classicism's influence on photography was subtle yet significant. Sander divided people into groups based on profession and class, arranging society into types and using photography to illustrate these types, with the belief that such a typology would provide a catalogue of humanity. This belief in the existence of universal archetypes is in keeping with the interwar interest, among those involved with the classical revival, in stripping humanity of complications in search of unadulterated ideals. Sander's image draws also to the influence of classical theatre, with the setting used to underscore existing ideas of professional hierarchy; Sander believed that laborers were among the lowest in society and associates the coal carrier with the basement from which he emerges in order to suggest that this place was spatial or inevitable, rather than socially constructed, and to invest this hierarchy with a nobility implied by the man's idealized costume and confident step.

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Barcelona Pavilion

The Barcelona Pavilion, designed to represent Germany at the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition, is a single-story building of glass, steel and marble. The pavilion consists of a number of low, intersecting rectangles, with the structure itself balanced by and reflected in a shallow pool in a large courtyard. The primary structure has a flat roof which overhangs glass and marble walls. Inside, visitors found only simple furnishings and textiles, designed and arranged by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich. Outside, posed on a plinth in the reflecting pool, is a neoclassical sculpture of Georg Kolbe of a young man, celebrating the idealized male body, athletic and proportionate, entitled Dawn.

Mies and Reich's Barcelona Pavilion is unusual in that it was designed solely as a reception space, free from the constraints imposed by housing exhibits, as was usual for national pavilions at International Exhibitions. In the absence of content, the building itself became the exhibit, drawing attention to the quality and polish of the materials; Roman travertine, green Alpine marble and gold onyx appear as if works of art. Given the context, such materials - closely linked with the ancient Mediterranean - served to link Germany with the classical empires of Greece and Rome. The strength of the building lies primarily in the ways in which classical influences are reimagined in a modern vocabulary. The Barcelona Pavilion, unlike many other interwar buildings, was not overtly neoclassical, with a free spatial plan and no reference to the classical orders, but reconciled the traditional and the modern through subtle links. The ratios of the plan and profile of the Barcelona Pavilion draw their rhythm from Euclid's golden ratio, while the placement of the structure on a large podium of marble creates a sense of the space as analogous to a classical temple. This building indicates the presence of classical influence even in architecture that looked forward and aspired to modernize, rather than celebrating the past.

The Street

This Parisian street scene shows the lives of a number of figures, distinguished by costume and activity, overlapping against a backdrop of shopfronts and awnings. On the left, a man grabs a young girl, gripping her wrist and pulling at her skirt, pressing his body against her, while she resists, her body leaning forward. Below her, a child plays with a ball; in the background, a baker, easily identified by his tall white hat, walks with his hands in his apron pockets. At the center, a worker in white carries a large plank that obscures his face. On the right, a man in a suit strolls along the road, toward the center, while two women, with long skirts and pronounced waists, walk away, their backs to the viewer.

The Street draws upon classical precedent in order to mythologize everyday life, imbuing it with a sense of timelessness. The receding street and the flatness of the facades, combined with the placement of most figures in the foreground, creates a sense of the painting as occurring on a stage, heightening the grandeur of quotidian life. This technique borrows from that of Piero della Francesca, whose work Balthus had studied, as do the soft, warm colors; the pinks, creams and browns recall early Renaissance frescoes and Italian churches and create a dreamlike mood. This mood, which heightens the remove of these figures from the viewer and imbues the scene with a sense of timelessness, is heightened by the scene's subtle divergence from the lifelike, with figures that pay no attention to one another despite their close proximity. This eerie independence is made particularly obvious by the assault occurring on the left side of the canvas, overlooked by those sharing the space, locked into their own predetermined activities. Balthus's use of colors associated with the ancient and Renaissance worlds, along with his theatrical treatment of space, indicates the ways in which Classicism and modernity were increasingly linked during the interwar period.

Oil on Canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air

This triptych represents the four elements as nude women, posed atop a bench before a blue backdrop, their feet resting on a neatly paved black and white floor. The left panel shows a fair-haired woman holding a torch, representing fire; she is placed at the center of the panel, with knees turned inward toward a red towel. This composition is mirrored in the right panel, representing air; the woman, here, holds nothing, her hands instead resting on the bench, beside her yellow towel, while her blonde curls flutter lightly, as if blown from behind her ears. There are two women in the central panel; Water, dipping her fingers into a bowl, looks down toward her knees, sitting atop a turquoise towel, while Earth, holding a bundle of corn in her right arm, looks toward the right side of the panel and lifts her white towel with her left hand. These women are all beige-skinned, with rosy cheeks, and have small facial features, light hair, and clearly defined breasts, waists, and hips.

The Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air is representative of the ways in which Neoclassical painting served to reinforce conservative discourse during the 1930s. The women in this painting represent the Aryan ideal favored by the Nazi party; the use of such figures as archetypes positions such figures as universal ideals for physical beauty. These women, who do not meet the viewer's gaze, appear calm and unthreatening, while the polished realism and balanced composition provide a sense of satisfaction and completism, offering a vision that could be balanced against the chaos and fragmentation that the Nazi Party ascribed to modern life. This painting was installed by Adolf Hitler above his fireplace in Munich and Adolf Ziegler was appointed Director of the Reich Chamber of Visual Art, a position from which he labelled certain artists and styles as "degenerate," linking morals and aesthetics in his promotion of classicism.

Oil on Canvas - Sammlung Moderner Kunst in der Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Beginnings of Interwar Classicism

Following World War I, with an estimated twenty million deaths and widespread destruction, European society sought new ways of coming to terms with modern life. Artists and writers, prior to the war, had largely celebrated modernity through experimentation with new forms of expression intended to match the potential of new technologies. World War I, a conflict through which modernity became closely linked with destruction, led to widespread uncertainty as to the appropriate response to the tragedy and to other changes associated with industrialization and globalization. Artists responded to this ambivalence in a range of ways, among which was a nostalgia for the past that manifested itself in the revival of classical aesthetics and ideas.

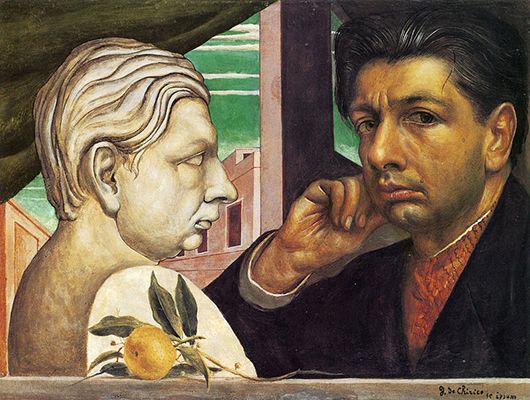

A New Classical Order

The origins of Interwar Classicism can be seen in the work and writing of conservative artistic figures, such as Maurice Denis, prior to World War I, but became widespread and polymorphous in the 1920s and 1930s, shaping avant-garde movements alongside the mainstream. Denis was a prominent critic of the desire to capture life as it was experienced, instead arguing that art should fulfil a spiritual function. His own painting practice focused on nudes after Renaissance sculptures, attempting to balance rationality with sensuality. He set out his beliefs in a book, Theories: From Symbolism and Gauguin Towards a New Classical Order, published in 1909, which argued that art should aspire toward the nobility and order he associated with classical sculpture. He celebrated Paul Cézanne, who rejected the Impressionist enthusiasm for ephemeral visual perception in favor of a more material approach, and encouraged others to follow Cézanne's example.

France and Purism

During World War I, those involved in more avant-garde movements, such as Cubism, began to have misgivings about contemporary practices. In 1916, Amédée Ozenfant, a prominent Cubist painter and writer, announced a "crisis in Cubism" and argued that it was necessary to streamline the movement by looking again at Classicism. This was due, in part, to the increased popularity of Cubist style, which Ozenfant felt encouraged artists to repeat themselves, thereby transforming Cubism into something predictable and easily commoditized. It was due also, however, to nationalist sentiments encouraged by the war.

Purism, Ozenfant's answer to this problem, was among the earlier adoptions of classicism toward avant-garde ends. Ozenfant, with architect and painter Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (later known as Le Corbusier), published a manifesto entitled After Cubism (1918), which argued that the end of the war meant a need for "order and purity" to organize and clarify life. Ozenfant explicitly linked this with the pain of World War I, writing that "faced with agony, the civilized pull the curtain." These ideas were adopted by others, including Fernand Léger, who combined a modern interest in abstraction, flatness and the machine-made with classical themes and simple compositions. Le Corbusier's buildings, like Léger's paintings, borrowed from classicism an interest in simplicity and refinement whilst rejecting the more obvious features of the aesthetic, such as columns, porticos and symmetrical plans, adopting a more utilitarian approach. These artists, aesthetically, adopted Classicism without rejecting Modernism.

Italy and Novocento

In Italy, classicism had long been linked with national pride and the growing interest in returning to antiquity and Renaissance ideals drew attention to those artists who rejected the more avant-garde Futurism often associated with interwar Italy and the celebration of modern warfare. In 1918, Carlo Carrà published an essay, 'Our Antiquity,' which criticized the zest for originality and novelty, arguing instead that Italians should look to their celebrated past. Giorgio de Chirico shared Carrà's reverence of the past, publishing 'A Return to Craft' in 1919; in this essay, de Chirico argued that artists should study classical sculpture extensively in order to learn from it.

After the war, as nationalistic fervor intensified in Italy, other painters joined Carrà and de Chirico in their celebration of the past. In 1922, Il Novecento Italiano, a group of artists who aspired to create an artistic style based on the ideas of Benito Mussolini, was formed, focusing their efforts around classicism, though Mussolini himself spread his support across a range of artistic movements. Carrà was among the members of the group, alongside others including Leonardo Dudreville and Achille Funi; their collective work sought to celebrate Mussolini through works that aligned him with the nobility and glory of the Roman empire.

Germany and Neue Sachlichkeit

Carlo Carrá and Giorgio de Chirico's essays were both quickly translated into German, extending their influence beyond Italy. In 1921, painter and theorist Max Doerner wrote The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting, a book intended to guide German artists away from Expressionism, which he viewed as too exuberant and undisciplined for the somber mood of the post-war era. Doerner, like de Chirico, associated classicism with craftsmanship and wrote that this attention to craft was a "road to lead us out of the chaos," basing his book on studies of Flemish and Italian Renaissance art.

The German variant on Interwar Classicism was labelled as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). The artists involved with the movement, including Max Beckmann and George Grosz, aspired toward representational art, unemotional and realist rather than abstract and dynamic, as was the case with other artworks associated with Weimar Germany; the New Objectivists, alongside the Expressionists, would come to be condemned in the 1930s, however, as representative of Weimar decadence and immorality. The classical was associated with the timeless and with a conservative model of beauty, with Michelangelo and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres chosen as models for contemporary artists to follow. New Vision photography, adjacent to New Objectivity, borrowed from its classical presentation, representing subjects against sparse backdrops, whilst maintaining a more avant-garde interest in the possibilities of contemporary life.

More broadly, Germany's classical turn manifested itself in a widespread interest in the idealized body, with emphasis on health as depicted physically through the sculpting of the human form. This was seen in the popularity of gymnastics, dance and sport, but was also clearly evident in the widespread adoption of the body as a subject in art. This interest was shared across the political spectrum, with those on the left associating this interest in the body with ideas of the collective and the proletariat while those on the right saw physical strengthening as closely linked with national strengthening, having lost the war.

Interwar Classicism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Painting

Across Europe, painters influenced by classicism worked in traditions including portraiture, the allegorical nude, still life and landscape, selecting their subjects and modelling their compositions after those of antiquity, the Renaissance, and the neoclassical period that followed the French Revolution. The early twentieth century, including the interwar period, was a time of immense artistic fracturing, with a variety of different styles emerging to make sense of the changing world. These included Dada, which celebrated the absurdity of modern life through mixed-media work, Expressionism, known for being raw and emotional, and Cubism, which fractured and reorganized the world into hard lines and abstract spaces. Classical painters argued against these styles, seeing them as individualistic in a time when rebuilding required collective endeavor and as inappropriate for nations traumatized by World War I, alternately labelling avant-garde approaches as too playful or too disturbing.

Interwar Classicism was distinguished by easily readable images that sought, through developed technique, to conceal their painting process, directing the audience's attention on the represented object rather than the means of representation. Prominent painters, including Jacques Mauny, Mariano Andreu and Gino Severini, utilized cool tones and traditional compositions, with clearly delineated foreground and background. This shift toward the traditional did not simply mean painters who favored classical styles came to prominence, but also that some associated with avant-garde traditions reconsidered their practice, as was the case for Pablo Picasso and André Derain, both of whom moved toward naturalism, with a focus on traditional draftsmanship and refined shading, in their representations of the female body. Others, such as Fernand Léger, maintained their interest in modern forms of representation even as they turned to traditional genres such as still life and portraiture.

Sculpture

The increased popularity of classical styles during the 1920s and 1930s contributed to the prominence of sculpture, believed by many to be the most appropriate form for art. Marble, associated with the works surviving from antiquity, was favored by sculptors and patrons, speaking to a desire for the solid, permanent and stable. The material was used in styles akin to those of antiquity, with an emphasis on smooth, considered carving. The Romantic style associated by Auguste Rodin, whose rough figures favored emotion and movement over finish, was usurped by the more academic tradition associated with Aristide Maillol, who sought to position the viewer at a remove, separated by plinths and by poses that provided a sense of unity and self-contained wholeness, so as to prompt evaluation of work intellectually rather than emotionally. This approach was followed by others throughout Europe, including Henri Laurens in France, Georg Kolbe in Germany, and Guido Galletti in Italy.

Sculpture, the quintessential classical medium, was especially strong in interwar Italy - the home of Michelangelo, Donatello, and Bernini. Artists such as Maillol, Guido Galletti, Georg Kolbe and Henri Laurens found sanctuary in the literal solidity of works of sculpture, and the requirements of care and craft taken in their production. Silver said: "Sculpture, the three-dimensional vestige of classical humanity in its least abstract, most tangible form, played an important role in art discourse between the wars. As both the symbol of an ancient heritage and the correction for unreliable, contingent, perishable life, sculpture became a touchstone for the arts."

As such, painters across Europe depicted themselves as sculptors in studios; Julius Bissier and Giorgio de Chirico for example, while others such as Suzanne Phocas and George Scholz would include paintings of busts and statues on their canvases.

Architecture

The politicization of the visual during the interwar period is clearest in evaluating the neoclassicism of European architecture, much of which was state-sponsored. The French, Italian and German governments all chose, as they rebuilt after the destruction of the war, styles that prompted comparisons with classical empires. These buildings were often monumental, symmetrical and made of stone, often lined with columns or topped with porticoes, in order to impress a sense of strength and order on visitors, but were often stripped of decorative detail and geometrically sharper than their classical precedents. Adolf Loos, a Viennese architect based in France during the 1920s, played a significant role in shaping modern attitudes to ornament, arguing that decoration was hierarchically beneath structure and linked with less 'civilised' races, an argument that appealed to European audiences uneasy about an influx of immigrants from the colonies after World War I. These ideas had an impact across the aesthetic spectrum, with conservative factions rejecting decoration in order to emphasise their place in a European tradition while the avant-garde embraced white walls and minimal detailing in order to emphasise utilitarian value and structural innovation.

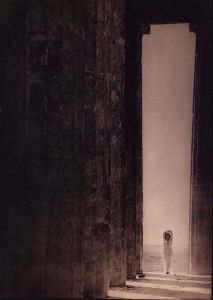

Photography and Film

The influence of classicism on photography in the interwar era can be seen in pared down compositions and historical allusions. Photography, as a very recent development, had no clear precedent to which to look, and so photographers' approaches to classicism are often more playful and irreverent than those taken by artists in other media; Edward Steichen, for example, photographed Isadora Duncan in a white dress framed by the Parthenon, emphasizing her mythical status in the world of dance, while Karl Blossfeldt entitled an image of maidenhair ferns Nature in Ionic Mood (1924).

The engagement of film with classicism is indicative of the multiplicity of approaches to the past employed in interwar art. Jean Cocteau, whose phrasing of the period as offering "a return to order" was borrowed by Kenneth Silver as descriptive shorthand for Interwar Classicism, largely rejected the call to intellectualism and remove that drove conservative painters, sculptors and architects. Instead, Cocteau and others were inspired by the Dionysian love of pleasure and literary tales of surreal transformation and dreamlike journeys, the influence of which can be seen in Cocteau's Blood of a Poet (1930), in which a young artist is lured through a mirror by a statue, and René Clair's The Imaginary Voyage (1925), in which a young man follows an old woman through a fantasy that moves from modern to medieval.

Later Developments - After Interwar Classicism

Fascist Era

As Europe moved closer to World War II, classicism became increasingly linked with authoritarian governments. In Italy, Benito Mussolini's interest in reviving the Roman Empire leant itself to the efforts of Il Novecento Italiano, even as Mussolini continued to court the support of both classical and modern artists. Across the French Empire, the use of European styles to represent Metropolitan French institutions, while local styles were used for local institutions, lead to the association of classical architecture with European control.

The links between conservative artistic styles and fascism became unassailable in Germany, where classicism became indelibly associated with the Nazi Party. Adolf Hitler, who had trained as a painter and felt modern styles to be responsible for his failures as an artist, deployed classical models to support his eugenicist policies. The widespread interest in health and fitness was coopted as a means of propaganda, with idealized classical bodies presented as models for a German race. The Great German Art Exhibition and the Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937 linked aesthetics with morality, labelling expressionism and Dada as decadent and corrupt. The political use of art by the Nazi Party reached its zenith with Leni Riefenstahl's film Triumph of the Will (1935), which positioned Adolf Hitler as a Wagnerian hero, introducing order and unity to Germany.

Into Contemporary Art

The Nazi Party's propagandistic use of classicism led to subsequent wariness. After many years, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, artists and architects involved motivated by a range of different factors have attempted to revive classical styles and subject matter. These have been particularly prominent beyond Continental Europe.

In the late 1960s, a movement critiquing modern architecture, New Urbanism, emerged to advocate for a return to classical principles. In the United States, this manifested in the creation of Classical America, now known as the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, an organization arguing for the preservation of historic buildings and their continued presence in architectural curricula; in the United Kingdom, the Prince's Foundation for Building Community plays the same role. While advocates for New Urbanism claim that classical townscapes provide pleasant experiences for those living in and visiting them, many prominent advocates for the classical revival in architecture, including Quinlan Terry and David Watkin, have been outspoken about their conservative political beliefs, linking a perceived decline in morality to changing aesthetic standards and thus contributing to an ongoing association of classical architecture with repressive politics. In the 1980s, postmodern architects, such as Michael Graves, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, began to deploy classical motifs in unconventional ways in order to challenge hierarchies and critique the staidness of the academic establishment.

In visual art, approaches to classicism have been more subversive, with artists borrowing from classical traditions in order to expand consideration of race, sexuality and gender. Bill Viola's Nantes Triptych (1992) adapts a form associated with religious traditions to open up questions of what has enduring value in a culture where science is valorized. While Léo Caillard's interventions into sculpture, dressing figures in contemporary clothing, challenge the associations of allegorical figures and prompt considerations of culturally-constructed presentation of the self. Felix Gonzalez-Torres's Untitled (Orpheus Twice) (1991) plays with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, revising the story through which Orpheus destroys Eurydice through his gaze in order to consider gender dynamics and the role of the audience in art. Other works, such as Patricia Watwood's Susannah in the Moonlight, are revised simply through their presentation in a contemporary setting; this painting of the Biblical story in which two men threaten to blackmail a young woman takes on unsettling tones when painted in the context of the #MeToo movement.

Useful Resources on Interwar Classicism

- Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy and Germany, 1918-1936Our PickBy Kenneth E. Silver / Guggenheim Museum / April 30, 2011

- On Classic Ground: Picasso, Leger, De Chirico and the New Classicism 1910-1930Our PickBy Elizabeth Cowling and Jennifer Mundy / December 1, 1990

- Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914-1925By Kenneth E Silver / April 6, 1992

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI