Summary of Identity Art & Identity Politics

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have seen many artists use art as a way to present their authentic life experiences, interrogate social perception of their identity, and critique systemic issues that marginalize them in society. These include women artists, artists of color, LGBTQ+ artists, disabled artists, and indigenous artists. Their art as well as activism have transformed the curatorial practices of the art world and made a profound contribution to the social and political spheres related to the rights of minority groups. While the term "identity politics" gained traction in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s to designate art that deals with issues of identity (especially race, gender, and sexuality), it has fallen out of favor since then, with many critics asserting that it has had a reductive effect, turning artists into tokenized representatives of one particular identity and further contributing to a view of identity as innate and fixed rather than socially constructed. Aware of this potential pitfall, many contemporary artists working with identity issues have instead worked to highlight the complexity of identity as an evolving lens of social analysis.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- There is no one type or style of Identity Art, but the term can be a useful umbrella for understanding artistic practices that prioritize questions of artists' identities and the art world's reception of their works. Many artists have argued that the default expectations of the art market and curatorial establishment are rooted in white, male, and hetero-normative experience. Identity Art can be seen as an attempt to redress this imbalance, and to encourage reflection on operations of art history that have systematically disadvantaged those whose artworks did not conform to these expectations or address similar concerns.

- Despite an often poorly-framed debate around its importance, art engaging with identity has led to greater awareness and major changes in the way museums, galleries, and critics treat work by historically marginalized groups. Decolonization initiatives, diversity programs, and critically reflexive curation are all legacies of Identity Art and Identity Politics.

- A risk for artists engaged in Identity Art is the potential to have their work read only in relation to one issue or social struggle, so many artists today deal with issues of identity through the lens of "intersectionality," which views different facets of identity (such as race, sexuality, age, etc.) as intertwined. Relatedly, the concept of "performativity" (the theory of identity as fluid yet enforced by social conditioning) complements this view.

- Identity Politics is a concept which has far-reaching implications in both the art world and other mediums of cultural production. In the 21st century debates around its influence on the production of film, television, and video games have been robust, and in many cases mirror or pre-figure critical and curatorial controversies in museums, galleries, and the art market.

Overview of Identity Art & Identity Politics

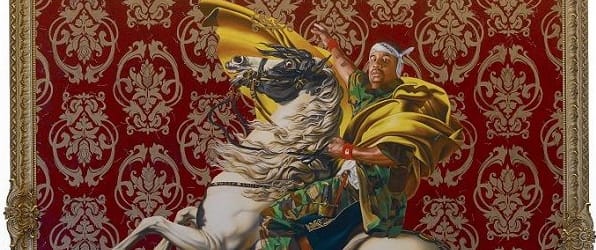

African-American artist Kehinde Wiley stages encounters between the white past of art history with his present by inserting a black subject into his re-creations of Western masterpieces. The insertion invites reflection on history, exclusion, and marginalization of non-white peoples. The models for his paintings are usually everyday people he asked to pose for him; he calls it his "street-casting process." Here the neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David's painting of a triumphant Napoleon (Napoleon Crossing the Alps, oil on canvas, 1803) gets a remake with a black man taking place of the Emperor, his camouflage gear, Timberland boots, and bandana wrapped around his head bringing the work to the contemporary.

Artworks and Artists of Identity Art & Identity Politics

Dinner Party

This installation is comprised of a large triangular ceremonial banquet table set with 39 place settings, each of which commemorates a significant woman from history. Each of the three sides (or "wings") of the triangle represent a different period from history. Wing I includes women from Prehistory to the Roman Empire, such as Primordial Goddess, Fertile Goddess, Ishtar, Kali. Wing II includes women from the beginnings of Christianity to the Reformation (for example, Marcella, Saint Bridget, Theodora), and Wing III includes women from the American Revolution to more contemporary feminist thinkers, including Anne Hutchinson, Sacajawea, Caroline Herschel, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, among others). Each place setting features elaborately embroidered runners, featuring a variety of needlework styles and techniques, gold chalices and flatware, napkin with gold edges, and hand-painted china porcelain plates that contain raised vulva and butterfly forms (each of which was created in a style that represents the individual woman the place setting was made for).

Chicago completed this work over the course of five years with the assistance of over a hundred volunteers and artisans (male and female). It was first exhibited in 1979 and is now permanently located at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Chicago's goal with the work was to "end the ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record." She came up with the idea while attending a dinner party in 1974, at which, she recalls, "The men at the table were all professors, and the women all had doctorates but weren't professors. The women had all the talent, and they sat there silent while the men held forth. I started thinking that women have never had a Last Supper, but they have had dinner parties." Women were selected for inclusion based upon the following criteria: making a worthwhile contribution to society, striving to improve the situations of other women, making an impact on women's history, and serving as a role model for a "more egalitarian future".

Dinner Party was a watershed moment for the centralization of female stories within an artworld context. It also provoked significant discussion around the correct way to represent women and their experiences. Although not universally praised by feminist critics (due to what some view as its essentialism), the piece asserted powerfully the necessity of engaging with female stories and brought into sharp relief the politics behind their previous exclusion. The work serves as an example of how women/feminist artists attempted to revise the (art) historical canon, calling attention to the historical accomplishments of women as a way to challenge the male-dominated nature of history writing. Such questioning provided a seed for other ways of dismantling assumptions around "talent" and artistic greatness that had been used to hinder the visibility of other minority groups in the art world, such as artists of color. Widely recognized as a classic of Feminist Art, Dinner Party can also be understood as an important precursor to Identity Art.

Ceramic, porcelain, and textile installation - Brooklyn Museum, New York

The Black Factory Archive

A traveling caravan, a community engagement initiative, a catalyst for conversation, Pope.L's The Black Factory Archive invites participation wherever his white truck stops with a deceptively simple proposition: Passers-by are asked to contribute an object that represents "blackness" to them. This process opens up space for reflection about which objects are associated with blackness (and why?) and what kind of history, social construction, and stereotyping are involved in the inscription of identity onto objects. Nearby, a gift shop is set up with everyday consumables and objects such as canned foods, bottled waters, t-shirts, and the ubiquitous yellow rubber duckies labeled The Black Factory. His truck always travels with a group of "staff"/performers, who "operate" the Factory, act out skits, and interact with the public. "The idea," the artist reflected, "is to maybe bring back some sense of a public square kind of atmosphere....You want people to feel that they can enter the discussion. At the same time, I don't want them to get the idea that the discussion is going to be easy."

While racial identity is often seen as inherent based on biological markers such as skin color, historians and theorists have shown how the category of "race" itself was a social construct that only emerged from the eighteenth century onward, with the confluence of Enlightenment classification thinking and the white subjugation of peoples racialized as Other and therefore "savage" and inferior. The history - and continuing reverberations--of slavery in America is inextricably tied with this theory of race. Born in 1955, African-American Pope.L makes provocative works drawing on performance, public intervention, and other mediums that confront viewers with America's slavery past and the present experience of blackness today. By asking an open-ended question about identity, the Black Factory Archive demonstrates the multiple viewpoints that can be brought to bear on an identity. It also highlights how, in addition to individual and collective histories, material culture, too, plays a crucial role in the shaping of identity and vice versa.

Performance and moving installation - Museum of Modern Art

Artifact Piece

In this performance, Luna lay in an exhibition case in the section on the Kumeyaay Indians in San Diego's Museum of Man wearing only a leather loincloth. Around his body, he placed labels describing the origins of his various scars (for instance, "excessive fighting" and "drinking"), as well as several personal effects, including ritual objects used currently on the La Jolla reservation, where Luna lived. Also included were Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix records, shoes, political buttons, college diplomas, and divorce papers. Luna lay in the case for several days during the opening hours of the museum, occasionally surprising visitors by moving or opening his eyes to look at them.

Luna (1950-2018) was a Payómkawichum, Ipi, and Mexican-American artist, born in Orange, California, who moved to the La Jolla Indian Reservation in California at the age of 25. The following year, he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of California, Irvine, and seven years later a Master of Science degree in counselling from San Diego State University. His goal with this work was to bring attention to how cultural institutions tended to romanticize or present indigenous culture as extinct, lost, or pure and untouched by change. As art critic Jean Fisher writes, Luna was thus exposing "the necrophilous codes of the museum," that is, the way that cultural institutions make corpses out of living Indigenous peoples and cultures. Luna remarked: "I had long looked at representation of our peoples in museums and they all dwelled in the past. They were one-sided. We were simply objects among bones, bones among objects, and then signed and sealed with a date." By directly confronting museum-goers with his own living, breathing body, he forced them into a jarring moment in which they had to confront their own ethnographic assumptions and prejudices. He recalled that many of the visitors spoke about him as if he weren't there, even after they realized he was, in fact, alive.

The array of ritual and secular objects with which he surrounded himself served to further emphasize the hybrid reality of contemporary indigenous life and culture. He said of the work, "In the United States, we Indians have been forced, by various means, to live up to the ideals of what 'Being an Indian' is to the general public: In art, it means the work 'Looked Indian', and that look was controlled by the market. If the market said that it (my work) did not look 'Indian,' then it did not sell. If it did not sell, then it wasn't Indian. I think somewhere in the mass, many Indian artists forgot who they were by doing work that had nothing to do with their tribe, by doing work that did not tell about their existence in the world today, and by doing work for others and not for themselves." Luna went on to explain that "It is my feeling that artwork in the medias of Performance and Installation offers an opportunity like no other for Indian people to express themselves in traditional art forms of ceremony, dance, oral, traditions and contemporary thought, without compromise. Within these (nontraditional) spaces, one can use a variety of media, such as found/made objects, sounds, video and slides so that there is no limit to how and what is expressed." In this way, he challenged the white gaze that objectifies others, such as Native Americans. As Fisher writes, Luna aimed to "disarm the voyeuristic gaze and deny it its structuring power," by placing himself in a position of power (as he was in control of when and to whom he chose to reveal his 'aliveness,' thereby implicating museum-goers in the performance without their previous knowledge or consent). This strategy has also been undertaken by other indigenous artists and artists of color, most notably Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Coco Fusco, and the performance group La Pocha Nostra.

Performance - San Diego Museum of Man

Rainbow Series # 14

This image uses collage to splice together images taken from postcard photographs produced in South Africa in the 1990s and Western pornography. A bizarre hybrid creature is thus created, comprised of a Black African topless female from the waist up, and a white naked female from the waist down, wearing knee-high red leather boots and thigh-high red fishnet stockings. The white female hand, with red painted fingernails, provocatively reaches around her buttocks to hold open her vagina to the viewer.

South African artist Candice Breitz was born in Johannesburg in 1972, and currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany where she also works as a professor at the Braunschweig University of Art. In Rainbow Series, Breitz explored and critiqued the competing cultural representations of, and influences on, post-Apartheid South Africa. In the wake of Apartheid, South Africa sought to re-negotiate its identity as the "Rainbow nation" (a national slogan adopted for a time in the 1990s), that is, a country in which individuals and communities of various ethnic and cultural backgrounds co-existed peacefully. Part of this project involved the production of tourist postcards, many of which presented indigenous-looking Black Africans in rural settings. The images, however, were carefully constructed, and used models rather than "real" people. At the same time, South Africa was beginning to open its doors to foreign media, which led to the importation of a significant amount of Western pornography. Thus, during the 1990s, South Africans were flooded with highly sexualized images that almost exclusively featured white women. Breitz stated that the images in the Rainbow Series "were my response to the contagious post-Apartheid metaphor of a South African 'Rainbow Nation,' a metaphor which tends to elide significant cultural differences amongst South Africans in favour of the construction of a homogeneous and somehow cohesive national subject."

The photomontage technique used by Breitz in this series is anything but polished, with her cuts between the images harsh and crude. For Breitz, this method served as a metaphor for the violence that continues to be carried out against women, as well as the ongoing, tumultuous process of identity negotiation in South Africa. As Brietz said, "It probably has something to do with my constant awareness of just how many women are getting cut up out there, literally or otherwise. [...] The Rainbow People are reconstituted as violently sutured exquisite corpses, fragmented and scarred by their multiple identities. They are far from the romanticised hybrid imagined by certain postmodern writers; or the seamless, slick, computer-generated images which some artists produce. Rather, at a time when porn is (at least for the moment) freely available in South Africa for the first time in decades, and when inner Johannesburg maintains the dubious distinction of having one of the highest rape and murder rates in the world, this series is, specifically, a perverse take on the composite subject making up the imaginary tribe which is said to populate the "New" South Africa." This use of photomontage is an example détournement, a Situationist strategy that re-uses preexisting media in a way that is critical of or oppositional to the original.

With The Rainbow Series, Breitz calls attention to intersectionality, or the multiple, overlapping, inextricable aspects of identity that complicate one another, such as the way that gender identity is further complicated by racial identity. In a 1996 interview she reflected that "Although we're focusing our conversation on gender here, I think the discussion must be extended to other struggles around identity, for example race or class or ethnicity. A feminism that does not take these struggles into account is not going to have any real power. We all experience multiple forms of identification, and our identity position is never exclusively 'male' or 'female' or 'black' or 'white.'"

Cibachrome print

Stories of a Body

This performance begins in a pitch-black room, and as the darkness and silence begin to grow uncomfortable for the audience, Duffy emerges, naked and harshly spot-lit from the front. Audience members are confronted by Duffy's "severely disabled" body, which bears a considerable likeness to the Venus de Milo, raising the ironic observation that one of art history's most iconic representations of feminine beauty is, in fact, armless.

Mary Duffy (born 1961) was one of the key figures in the development of Disability Arts in the UK. She is an Irish painter and performance artist who graduated from the National College of Art and Design in 1983 and went on to complete a Master's degree in Equality Studies from University College Dublin. In 2003, she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Laws by the National University of Ireland in recognition of her contributions to the international Disability Arts movement. Duffy was born without arms as a result of thalidomide poisoning. Thalidomide was frequently prescribed in the 1950s and early 1960s for the treatment of nausea during pregnancy. It was later discovered that the use of thalidomide during pregnancy frequently resulted in severe birth defects. From a young age, Duffy became adept at using her feet and toes to perform many of the tasks typically performed with hands, including drawing and painting.

Duffy recognized that the vast majority of representations of disability had not only been created by non-disabled individuals, but that they also had contributed to widespread and overwhelmingly deleterious attitudes toward understandings of disability. She writes, "In 1980, while at art college, I began to look at, and to question, my own fragile identity as someone who was very definitely different, disabled, and therefore, without any relevant cultural reference points. There were disability reference points all right, but they had been created by non-disabled people and regarded disabled people as tragic, pathetic, or brave. These images were so far removed from my own experience, I had to search for an image of disability I could be proud of, an image that did not reek of emotion or pity, an image that reflected disability as being a part of being human and all the richness and diversity that that entails."

Duffy performed this work at numerous venues between 1990-2000. Writing about the motivations and intentions behind Stories of a Body, she states "...in doing this performance, by standing here, naked in front of you, I am trying to hold up a mirror for you, I am making you question the nature of your voyeurism." In this way, Duffy's performance sought to challenge the particular mode of looking, or rather "staring" that historically characterized, and continues to characterize, visual encounters between the able-bodied and the visibly disabled. Duffy thus challenged viewers to recognize identity, disability, and difference as constituted through processes of looking and staring.

According to Critical Disability Studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, "staring" is an "intense form of looking [that] constitutes disability identity by manifesting the power relations between the subject positions of disabled and able-bodied." Garland-Thomson notes that "Staring at disability choreographs a visual relation between a spectator and a spectacle [...] By intensely telescoping looking toward the physical signifier for disability, staring creates an awkward partnership that estranges and discomforts both viewer and viewed [...] Because staring at disability is considered illicit looking, the disabled body is at once the to-be-looked-at and not-to-be-looked-at, further dramatizing the staring encounter by making viewers furtive and the viewed defensive. Staring thus creates disability as a state of absolute difference rather than simply one more variation in human form."

Performance - International Touring from 1990

Becoming an Image

In this performance originally carried out at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles, a 1500-lb block of clay sat in the center of a pitch-black room. Canadian, gender non-conforming and transmasculine artist Cassils proceeded to physically modify the block using the force of their own body, kicking and punching the clay in order to alter its form for 24 minutes. Photographs of the performance, which went on to be shown in other exhibitions of Cassils' work (alongside the modified blocks of clay), present the artist in the throes of this strenuous activity, grimacing and dripping sweat. Audio of the performance was also recorded and presented at subsequent exhibitions, with the sound of Cassils' physical exertion presented as an integral part of the work.

Cassils trained with a professional Muay Thai boxer to prepare for the performance in which they physically attacked the block of clay. Through the intense effort it required to physically re-shape the clay, Cassils offered a commentary on the amount of work it takes to develop and maintain one's body, and simultaneously, one's identity. The violence of their activity also alludes to the violence experienced by trans individuals around the world. Indeed, Cassils understands the modified block of clay as a monument to trans people's perseverance and fortitude.

The performance was carefully constructed to withhold full visibility from the viewer. Sporadic camera flashes from collaborator Manuel Vason illuminated Cassils for only brief moments, providing viewers with mere glimpses of the intense performance. This setting may be understood as a metaphor for the difficulty of seeing the work and endurance of trans people for cisgender individuals.

Performance - ONE Archives, LA / International Touring

Beginnings of Identity Art

While many artistic traditions and practices can be understood as an expression of identity, whether individual or collective, Identity Art in the twentieth century had its starting point in the questioning of the art world's gate-keeping that had excluded non-dominant groups from participation. In the 1960s, both second-wave feminism and the civil rights movement exposed how discrimination and prejudices based on gender and race worked in upholding the dominance of white, male, heterosexual artists, curators, and arts patrons. Although operating rather like parallel tracks at first, both movements created ripple effects that would converge in later decades.

Second-Wave of Feminism

The first wave of feminism, in the first half of the twentieth century, focused largely on legal issues such as women's right to vote. Building on this social activism, second-wave feminists in the 1960s and 70s drew attention to the broader relegation of women to the domestic sphere, and the way that Western society perpetuates stereotypes about "essential" female qualities and the "proper" role of women: a patriarchal hierarchy in which women are seen as inferior and subservient to men. Feminist artists during this period also aimed to draw attention to these issues in their work. Some sought to revise the art historical canon, as well as historical reflection more broadly, both of which had tended to exclude the accomplishments of women and focus only on the achievements of great men. Linda Nochlin's 1971 essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" was a foundational text in the call to address the imbalance within the art historical canon. Others sought to question stereotypes and the idea of gender essentialism, or the notion that gender (although the theory can also be extended to sexuality, race, ethnicity, etc.) is fixed, static, and unchanging, defined by innate/inherent traits. An essentialist view of gender states that women are inherently bad at math and science, for example, and this view has historically been used as justification for limiting educational and employment opportunities for women in these fields, further perpetuating the stereotype.

In 1975, British film theorist Laura Mulvey published an essay titled "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," in which she argued that narrative film (as well as other popular media formats) generally presents women as the object of a male scopophilic gaze, and, moreover, that female viewers participate in narcissistic identification, meaning that they receive pleasure from being objectified in this way. Mulvey's arguments echoed those of English art critic John Berger, who critiqued men's visual dominance in his 1972 TV series Ways of Seeing, stating that "Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. " Many female artists around this time sought to challenge this hegemonic norm in their art.

Civil Rights Movement and Push for Racial Equality

Concurrent with the second wave of feminism was the Civil Rights movement, during which African-Americans fought not only to gain equal legal rights, but also to combat racist stereotypes and to define their own identity and culture. This latter aim had its beginning in several arts scenes in the early twentieth century, particularly the New Negro movement and the Harlem Renaissance. By the middle of the century, African-Americans, as well as other racial minority groups (such as Native Americans and Latinx communities) were creating art with the aim of calling attention to ongoing prejudice and injustices against their communities, and with the intent of calling into question the supposed superiority of art made by white artists. Key thinkers who contributed to this critique include Frantz Fanon (a psychiatrist, writer, and philosopher from the French colony of Martinique), who wrote about the experience of being an oppressed black person living in a white-dominated society; Edward Said (a Palestinian-American professor of literature), who developed the field of postcolonial studies and is best known for his book Orientalism (1978) in which he critiqued the Western world's cultural representations of the "Orient" (historically meaning what is now northern Africa and the Middle East); and Homi K. Bhabha (an Indian critical theorist) who further developed Said's theories pertaining to postcolonialism. The Civil Rights movement and critical theories of race, ethnicity, and postcolonialism all have greatly informed artists working on various aspects of identity to the present day.

“Primitivism” at MoMA, “The Decade Show,” and the 1993 Whitney Biennial

In 1984, the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted an exhibition titled "'Primitivism' in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern," in which masterpieces of modern Western art were shown alongside "artifacts" from non-Western (mainly African and East Asian) cultures. Many critics of the show (and of the concept Primitivist Art) argued that the exhibition presented non-Western works as inferior to those of European and American artists rather than examining critical and historical dialogue between them. In response, curators from The New Museum of Contemporary Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and The Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, organized an exhibition in 1990, "The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s", which featured over 200 works by 94 artists from various countries and cultures who wanted to highlight and challenge the systemic exclusion of non-White, non-Western artists in major art institutions. Lisa Phillips, current director of the New Museum, said of "The Decade Show": "It took up homosexuality, gay sensibility, gender issues, and issues of race and identity. These were firsts in the museum world."

"The Decade Show" prompted many other institutions to address their treatment of non-white artists. One of the most significant outcomes of this shift was the organization of the 1993 Biennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which took as its main theme "the construction of identity." Then-director of the Whitney, David Ross, explained that contemporary artists "insist[ed] on reinscribing the personal, political, and social back into the practice and history of art." Ever since, artists like Kehinde Wiley, Renée Green, Byron Kim, Glenn Ligon, Pepón Osorio, and Lorna Simpson have continued to create art that provides a counter-narrative to the whiteness of Western art institutions.

Intersex, Queer, and Trans Rights Movements

Queer theory, first discussed by scholar Teresa de Laurentis in 1991, as well as the gay-, queer-, and transgender-rights movements (which gained momentum throughout the twentieth century), has been accompanied by many artists who have worked to foreground pressing issues within the queer community, such as HIV/AIDS (particularly in the 1980s), as well as ongoing struggles against violence and stigmatization. Here, "queer" is used to reclaim the formerly pejorative term which has been used to designate non-normative (non-heterosexual) sexual identities. This usage derives from the work of de Lauretis, and has been further developed in recent decades by later queer theorists. Overall, queer theorists and artists work to question and critique essentialist notions of sexuality, the widespread view in culture-at-large of sexual identities as fixed and biologically determined, as well as the heteronormative ideals of family life and forms of kinship that are historically and culturally conditioned yet often seen as "natural."

An important theoretical underpinning of queer theory is Judith Butler's concept of performativity. First theorized in 1988 in her work on gender, performativity dictates that gender is tenuously constituted in time through stylized repetition of acts. These acts constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self, rather than a stable identity from which various acts proceed. Gender is thus distinct from sex, which corresponds to the biological or medical differentiations between men and women (although the instability of this binary sexual division is now also widely acknowledged by medical and scientific professionals). Queer theory has prompted revisionist accounts of art history and re-readings of major artworks through a queer lens. In turn, artworks by queer artists such as Andy Warhol have provided a productive testing ground for new ideas in queer theory, such as in the writing of art historian and queer theorist Douglas Crimp.

Disability Arts

Canadian disability researcher Jihan Abbas writes that, "The emergence of disability culture, and the importance of art forms and representations in this culture, must be seen as a natural extension of the disability rights movement, as the disability arts movement is essentially about the growing political power of disabled people over their images and narratives." Artists working within Disability Arts create and disseminate representations of their lived experiences of disability, challenging the problematic ways in which the vast majority of representations of disability have been constructed in popular culture. An artist or work may be classified as being a part of Disability Arts based on the artists' personal identification, their medical diagnosis, the experiences they encounter in their day-to-day life, the subject matter of their artwork, or any combination of the above. As disabled writer Allan Sutherland notes, "The movement that we describe as 'disability arts' has developed [since the 1980s] as disabled people have rejected negative assumptions about their lives, defined their own identities, expressed pride in a common disabled identity and worked together to create work that reflects the individual and collective experience of being disabled." Many proponents of Disability Arts firmly oppose conflating Disability Arts with art therapy, as they view art therapy as a biomedical tool that focuses on healing and repairing "broken" bodies. In the confusion between the two, the agency, identity, and the aesthetic value of disabled artist's works are diminished.

Identity Art & Identity Politics: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Identity Politics

It may be useful to differentiate between Identity Art as a broad category of art that explores issues of identity, on the one hand, and Identity Politics, which was a more historically specific term that became common in the art world (and public discourse) in the 1970s-1980s. Identity Politics was used to designate art that addressed race, gender, and sexuality, especially in the US context. Amidst the rise of Reaganism and right-wing politics in the 1980s, Identity Politics became a derogatory term used by critics as a way to dismiss the artistic contributions and boundary-pushing artists of color and queer artists (by framing them as "merely" about identity, and thus not fitting in with the skewed standards of the white-dominated art world). On the other hand, such dismissals furthered the argument of supporters of Identity Politics in showing the headwinds faced by minority artists who wished to make art by drawing on their life experiences.

Since then, there has been more acceptance of identity-focused art, even as "identity" can become both an entry-point and a limiting condition. Curators Anders Kreuger and Nav Haq point out that "Artists are allowed access to the art system on the condition that they have to act, or be framed, as socio-cultural representatives of the place/people they 'are from.'" The rise of Identity Politics in the art world, they argue, resulted in a transition "from marginalization (on the outside) to ghettoization (on the inside)."

Many contemporary artists are fully aware of the pitfalls of engaging with identity. Some would argue, however, that they don't have a choice but to address it: As the contemporary African-American artist Tschabalala Self noted, "All artists create identity-based work, but only some artists are asked about their identity [...] If some artists seem to make work that is ostensibly unconcerned with these realities, it's because they are not made to feel marginalized by them." So long as systemic marginalization and violence against groups based on perceived identity remain, questions of identity will continue to be part of many artists' reality. The terms of the debates may shift, just as our understanding of identity has evolved, but until parity and equal access to opportunity in the art world is truly achieved (not only for artists but also among museum professionals and staff), the critical reckoning of the art world's system of critical and monetary valuation will continue to be urgent for many.

Identity and Politics through Art: Interventions

While identity-related concerns were slow to be taken up by many Western art galleries and museums, a great deal of progress occurred outside the confines of institutions. Artists have often taken their work outside of traditional gallery spaces, or used the space of the gallery itself in ways that "intervene" in their usual function. Artists may create work that is unable to be viewed in a conventional manner, or situate their work within a more politically or socially charged context. They may even intervene in everyday life, inserting their art and politics into normal conversations or social interactions.

Feminist Performance artists, in particular, have been taking to the streets for decades, such as Austrian artist Valie Export, who between 1968-1971 enacted a public performance titled Tap and Touch Cinema in ten European cities. For this performance, the artist wore a miniature "movie theatre" around her naked upper body, covered by a curtain at the front, so that passers-by could not see her, but were invited to reach in and touch. Her aim with this work was to confront the public, in a tactile manner, with a living, breathing female body, attached to a face which responds and looks back, rather than a simple (yet highly constructed) passive visual image on a page or screen, to which they were more accustomed.

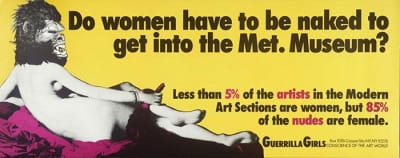

A later example is intersectional feminist group Guerrilla Girls, who have taken to the streets, putting up stickers, posters, and street projects in cities all over the world since 1985. The Guerrilla Girls' street interventions aim to highlight issues of injustice and inequality (both on the basis of gender and race) in the art world. For instance, in 1989, the group rented advertising spaces on buses in New York City, in which they inserted posters they had made calling attention to the fact that at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female."

Indeed, Street Art in its myriad forms has proven to be an ideal medium for artists who seek to address Identity Politics in their work, as it allows for uncensored expression in public locations with large numbers of potential viewers. For instance, Montreal-based MissMe, who works primarily in wheat paste posters, installs street art that challenges outdated patriarchal attitudes and empowers women. In a 2018 street installation, she called into question the male-centred Christian origin story (in which the first women grew from the first man) while simultaneously reminding viewers of the pain and sacrifice demanded of women as bearers of new life, asserting that "I didn't come from your rib, you came from my vagina."

Even when not literally on the street, artists engaged in Identity Art still "intervene" in the expected viewer/artist relationship. Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta's 1973 multi-media installation and performance Untitled (Rape Scene), for example, was a feminist piece created to foreground the high incidence of rapes and murders of women that were occurring on the University of Iowa campus while she was in attendance there. Audience members arrived via an elevator to be immediately confronted with the scene within the confines of a regular apartment, forcing them to contemplate a realistic scene of rape outside the distancing and "safe" space of a gallery. It was also possible that members of the campus community who were not aware of the performance could enter and think it the aftermath of a real assault, blurring the line between art and real experience. The work highlighted the urgency of the issue and the reality of being a woman at the time.

Public intervention has proved to be a highly effective strategy for artists of color seeking to create art that reflects the struggles of their communities, particularly in the context of living in predominantly white areas, states, and countries. American artist Adrian Piper, for example, who is African-American but could pass as white due to her light skin tone, carried out a performance in 1989-1990 titled My Calling Card #1, in which she passed out a small card in various social situations to individuals around her who made racist remarks in her presence. The card informed readers that Piper is in fact black, although they may not have been aware of that, and that the racist comment they had just "made/laughed at/agreed with" was in fact discomforting to her. The performance was one that played out within everyday life, with only the documentation (in the form of the calling cards themselves) available for display as a record of the intervention.

Disabled artists have also made regular interventions into the relationship between art and audience. An important early work of the Disability Arts movement is English artist Tony Heaton's 1989 sculptural intervention titled Wheelchair Entrance. The work was composed of a wooden board labelled "wheelchair entrance" which was hung across a gallery doorway at a height that blocked ambulatory visitors but permitted entrance beneath it to anyone in a wheelchair. The work acted as a simple but effective means by which to make gallery visitors aware of architectural barriers to mobility. Moreover, it encouraged an embodied engagement with disability by forcing ambulatory visitors to confront a moment of physical limitation without attempting to explain or analyze the encounter, simply allowing it to create meaning through the perspective of the body. This piece reflects the social model of disability now prevalent in civic and political discourse - the idea that it is not someone's body which disables them, but the society around them. A person is prevented from entering a building not because they use a wheelchair, for example, but because there is no ramp. Heaton's intervention in the space reflects this, with the space "othering" ambulatory visitors and preventing their easy access.

Identity and Politics through Art: Critique on the Gallery Wall

Issues and politics of identity are not only played out in non-conventional spaces or in ways that are unfamiliar to art audiences. Many artists create work fully able to be displayed and evaluated as more conventional painting, installation, or sculpture, whilst still maintaining a strong political message about identity. This critique from within the gallery system often intersects with Institutional Critique, the questioning of the gallery system itself.

Frida Kahlo's work frequently depicted her experience of disability in her self-portraits (namely, the numerous broken bones and fractures she experienced as a result of a bus accident when she was a teenager, as well as her inability to carry a pregnancy to term, also a result of the accident). Her work highlights the intersectional position of her identity as both a woman and an artist with a disability, foregrounding, when considered in detail, the relative lack of both in museum and gallery collections. Historically, few artists dealing directly with issues of disability in their work are represented in museum collections or the international art market, but Kahlo has achieved a high level of renown, particularly in the twenty-first century.

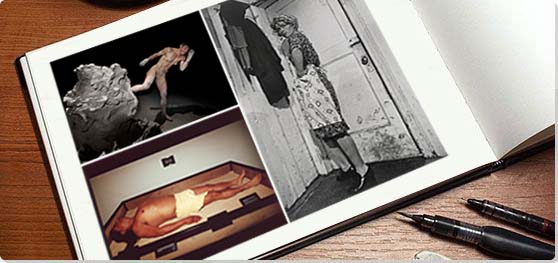

Other artists have drawn on their sexual identity explicitly in their work, with the rise of the gay rights movement (and related movements, such as the transgender rights movement) after the Stonewall riots in 1969 in particular encouraging LGBTTQQIAAP (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual, ally, and pansexual, henceforth referred to simply as "queer") artists to create works that take up issues prevalent in their communities, such as HIV/AIDS, violence, abuse, stigma, and acceptance. One notable example - of what is sometimes called Queer Art - is David Wojnarowicz, who dealt with pressing issues within the queer community in his work. Wojnarowicz was a target of the "culture wars" of the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, wherein artists dealing with sensitive (often identity-based) content and imagery in their works were attacked by various organizations (including the American Family Association and the Catholic League) on the basis of creating and disseminating what were claimed to be vulgar, immoral, or gratuitous images that were unworthy of the gallery. Other artists who fell victim to the "culture wars" (by being denied funding, as well as receiving harsh disparagement) include Robert Mapplethorpe, Andres Serrano, Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes.

Despite this political oppression, Wojnarowicz's work has now achieved significant curatorial interest, culminating in his 2018 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Like Kahlo's work, it draws attention explicitly to an injustice on the basis of identity and highlights the absence of explicit acknowledgement of minority positions in curatorial agendas. The success of Identity Art is in part encapsulated by the reassessment and incorporation of ideas previously on the fringes into a mainstream process of art world acknowledgement.

Later Developments - After Identity Art & Identity Politics

Today many contemporary artists use art as a tool in the (re-)negotiation of multiple aspects of identity that operate together - or intersectionally - rather than separately. The term intersectionality was first coined in 1989 by race and gender law scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, who argued that an individual cannot be defined by a single identity, such as gender, but that different aspects of a person's identity work together to determine their social standing, privileges and/or disadvantages. These include (but are not limited to) gender, race/ethnicity/diaspora, sexuality, and disability, as well as class, body type, and age.

Other scholars have proposed using the term "post-identity (politics)", which is related to the concept of posthumanism. Post-identity thinking has its basis in the theories of Nietzsche, Foucault, and Deleuze and Guattari, and argues for an understanding of identity as a process of becoming, characterized by flux, change, impermanence, incoherence, and unpredictability. Many of today's identity-focused artists are incorporating ideas of post-identity into their works, such as the participants in a 2014 exhibition As We Were Saying: Art and Identity in the Age of "Post" at the EFA Project Space in New York. One sculpture in the show, In Spirit of (a Major in Women's Studies) by A. K. Burns and Katherine Hubbard, consisted of a wastebasket filled with various objects, including a studded leather belt, an electrical power strip, confetti, plastic snakes, and a rose made of feathers. These objects do not easily correspond to any one recognizable "identity," but invite multiple associations, even as they are found, after all, in a wastebasket evoking a sense of irrelevance or a lack of value. The work thus insists upon identity as incoherent and imperceptible rather than fixed and knowable.

With multiple facets of identity explored through art and with many artists moving beyond "identity" as such, Identity Art today may be understood less as a fixed category or style, but as an awareness that many artists bring to their artmaking processes (even so as to critique or complicate it). It can also be a critical and historical lens through which we can approach artworks, including those that were not made with "identity" in mind.

Useful Resources on Identity Art & Identity Politics

- Through The Flower: My Struggle as A Woman ArtistBy Judy Chicago

- Cindy ShermanBy Eva Respini and Johanna Burton

- Meet Cindy Sherman: Artist, Photographer, ChameleonBy Sandra Jordan and Jan Greenberg

- Women Photographers: From Julia Margaret Cameron to Cindy ShermanBy Boris Friedewalde

- Glenn Ligon: Encounters and CollisionsBy Glenn Ligon, Francesco Manacorda, Alex Farquharson, Gregg Bordowitz

- Kehinde Wiley: A New RepublicBy Eugenie Tsai

- Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s History and ImpactBy Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard

- Art and FeminismOur PickBy Helena Reckitt

- Disability AestheticsBy Tobin Siebers

- Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the MuseumBy Richard Sandell, Jocelyn Dodd, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson

- Cindy Sherman: The Complete Untitled Film StillsOur PickBy Peter Galassi

- Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art HistoryOur PickBy Kymberly N. Pinder

- How To See A Work of Art in Total DarknessBy Darby English

- Art and Queer CultureBy Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer

- Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of VisibilityBy Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton