Summary of André Masson

Painting dreamscapes of writhing mythological figures and tortured natural forms, André Masson combined the two main visual techniques of Surrealism: biomorphic abstraction and automatic techniques. One of the first painters to embrace André Breton's Surrealist theories, Masson channeled the subconscious and explored the themes of sexuality, violence, metamorphosis, and death that were central to the movement. His paintings reveal the inner workings of the mind through the exploration of dreams, desires, and paranoia.

Accomplishments

- After experiencing the violence and chaos of World War I, Masson incorporated brutal, disembodied images into his paintings with unprecedented graphic force. He combined these savage forms with ideas drawn from Friedrich Nietzsche to portray uncertainty and to question the reason for human existence.

- An admirer of early Renaissance and early modernism, Masson combined classical themes and emotionally-laden abstract forms. Many of his works draw from classical mythology as archetypes of life, sex, and death, breathing new life into traditional narratives and making them relevant to the post-war era.

- Like many of the Surrealists, he relocated to America during World War II, where his impact on the New York School was more direct. Masson's automatic technique and cosmic narratives were visually and thematically important to the development of Abstract Expressionism.

Important Art by André Masson

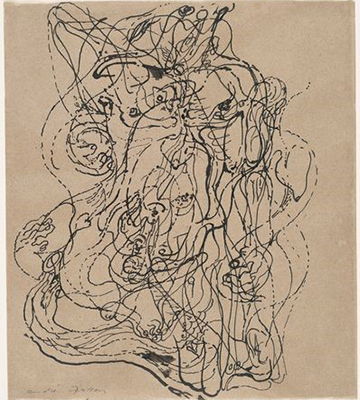

Automatic Drawing

This chaotic and multifaceted drawing demonstrates Masson's use of the automatic method. The linework is varied, ranging from thick to thin and includes some broken lines that show the unpremeditated nature of the work; he drew as inspiration came to him. The curves of these lines and bodily elements are complex.

Masson described automatism as "a kind of writing. A thing I used to do would be to throw a string onto a blank sheet of paper: what you see appear are movements of an undeniable grace." The string or line that connects all of these elements acts as a stream of consciousness, temporally binding them together. Yet, eventually all the elements blend together and one cannot determine where it begins or ends. This piece thus provides an example of quintessential automatism and gives the viewer a valuable insight into the processes behind it.

The viewer's attention is drawn to the center of the piece, which evokes a human presence. The amorphous nature and biological quality of the form suggests a conflict of multiple identities through the automatic method. Masson incorporates varying facial forms, which appear to be melting and hands, which grasp at nothing. But while the viewer can locate the presence of human features, they do not fit together to form a coherent figure.

Ink on paper - Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, NY

In the Tower of Sleep

A central figure is crushed by his surroundings while all around him are symbols of eroticism, death and destruction. Masson stated that the image "came from a memory of war...a figure lying in the trench with his head split open." There are several allusions to the trauma and aftereffects of war throughout the piece. The skinless nature of the figure alludes to the vulnerability of the body and the fragility of life as Masson witnessed in the trenches. Additionally, the agricultural elements and fire may also harken back to the setting and experience of warfare.

Human figures metamorphize into musical instruments and disintegrate into incomplete forms. The animated string instrument sawing its own strings with a bow suggests both sex and destruction while the main figure is shown without a phallus and instead leaks bodily fluid from a cavity. This theme is amplified by the woman who is transforming into a harp, but also remains a grotesque, fleshy distortion. These joint symbols of destruction and eroticism explore the longstanding associations between sex and death.

Another thread running through this painting is Greek mythology. The split skull resembles the pomegranate from the story of Persephone, who is doomed to remain with Hades in the underworld because she ate its seeds. This is reinforced by setting of the tower within an abyss from which there is no escape. The viewer is trapped in a nightmare. Like Persephone, Masson appears caught in a metaphorical underworld derived from his war trauma.

Oil on canvas - Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), Baltimore, MD

The Metamorphosis of the Lovers

In an image of swirling, intertwining, erotic forms, Masson mingles symbols of life and death. Two large figures can be deciphered, but both display elements of male and female genitalia. The female figure sits to the right, disemboweled, with a large shell-like vagina while her arm drapes across a phallic trunk. She leans back, an apple in her mouth to evoke the narrative of Adam and Eve, with its implications on both the origins of life and sexual temptation. The male figure's torso is also splayed as he tilts his head back, touching the female's shell (vagina) in an act of coital pleasure. From his open mouth emerges a flower, which scholar and curator Carolyn Lanchner has likened to a vulva; his genitals are thus central to the biological reproduction as "the entrance to life and the exit to death...the eternally recurring cycle." From the linked musculature of the two figures grows a flower, which art historian and author Martin Ries interprets as the production of a fertilized egg: "if her internal organs evoke the germinal force of fertilized seeds, does the growing flower represent their progeny?"

Posing a sharp contrast to these symbols of life and regeneration are the eviscerated torsos of both figures. Ries suggests that this juxtaposition is thus representative of the ongoing metamorphosis of the natural world; as one of Masson's favorite philosophers, Heraclitus, stated, "Out of life, comes death and out of death life...the stream of creation and dissolution never stops." Masson's piece is a meditation on humanity's unequivocal cycle of life, death and reproduction. The piece brims with juxtaposition and inner conflict between nihilism and optimism, and questions whether human existence is thoughtful and rational or simply animal.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Gradiva

Masson's Gradiva references both an ancient the marble relief, of Gradiva from the Vatican Museum and its early 20th-century appearance in a novel by Wilhelm Jensen that inspired Sigmund Freud. Jensen's novel traces an archaeologist's obsession with the ancient Roman relief, an obsession that crosses between consciousness and dream-states as he pursues a mysterious young woman. Freud studied this novel as a psychoanalytical case study of transference and the power of repressed memory. The Surrealists adopted Gradiva as a "muse" who could walk between real and surreal, the conscious and subconscious. When they founded a Parisian art gallery in 1937, they named it Gradiva.

The story of Gradiva also references the Pygmalion myth from Ovid's Metamorphosis, in which Pygmalion's marble statue of Galatea comes to life before his eyes, fulfilling his artistic and sexual desires. Masson's Gradiva embodies just the opposite of this awakening; half-stone and half-flesh, his Gradiva is cobbled together in the imagination of the artist. While her flesh is pink and supple, her stony half is white, hard and hollow. Her torso is a massive beefsteak and her vagina a shell. These qualities simultaneously overemphasize her sexuality and undervalue her humanity, as if she is only a slab of meat with genitals. She represents the liminality between the real and the surreal; she exists both in reality and in the dream of the artist and her physical state remains forever in flux.

Yet, unlike Pygmalion's Galatea, Masson's Gradiva represents a breakdown rather than fulfillment. The dreamscape surrounding Gradiva becomes fragmented as the viewer watches her turn to stone, reversing the narrative and conflating reality and dream. Her transformation is mirrored by the juxtapositions in the background, including the prominent eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which serves as an image of violent death, but also as a metaphor for sexual completion. What initially appear to be flies, a symbol of death, are actually regenerative bees flying out of Gradiva's knee with an overflow of rich honey.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Meditation on an Oak Leaf

Meditation on an Oak Leaf reflects Masson's reconnection with the natural world, as he and his family settled in Connecticut. Fleeing France in 1939, he had initially relocated to New York, as did many of the Surrealists who were escaping the war and Nazi persecution. It was, however, after they moved out of the city that he experienced a remarkable artistic revitalization, inspired by the changing seasons and a new feeling of ease within the natural world.

Although abstract, this piece is based in the natural world, organized in a series of cellular forms that suggest both plant pods and maternal wombs. Together, they form a feline form that contains multiple gestating fetuses within itself. Reproduction and metamorphosis are central in the composition and the significance of the piece, as are the biomorphic forms of plant roots and branches that weave throughout the work.

These interwoven motifs mimic the natural world's symbiosis between flora and fauna, unifying plant and animal life into a continuous, but ever-changing whole. The entire piece is dominated by the titular oak leaf, which art historian Doris Birmingham has suggested references both long life and death from being severed, calling it "his painterly fantasy on nature's organic processes." Masson's contemplation on the oak leaf and the gestating female invoke life's complex processes; while living creatures change and die, the natural balance remains continuous.

Tempera, sand and pastel on canvas - Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, NY

Pasiphaë

Pasiphaë, mythological goddess, queen of Crete, and mother of the minotaur (following a sexual encounter with a bull), represents the fertility of earth itself in this painting. Her genitals are clearly rendered, suggesting the importance of female sexuality, but also the bestial lust which led to Pasiphaë's disgrace. Inspired by the volatility of Masson's wartime memories and the dynamism of New England weather, the piece captures the explicit eroticism and deeply intimate nature of the union between Pasiphaë and the white bull, which occurred while she was under a curse from Poseidon. Masson claimed that, unlike other depictions, this was not overtly about coitus. He argued "there is a more interior union here. You can't see very well where the bull begins." Indeed, the boundaries between the two figures are obscured as they merge together.

In Masson's own words, "As for the sex of the woman, it is found in the center of the painting almost in an oblique line with the testicles of the bull. It is an entanglement...the second breast becomes a constellation. Everything in the universe in fusion." This piece positions coitus as more than an act of pleasure: it becomes a metaphor for the never-ending genesis and metamorphosis of the cosmos. In this reinterpretation, Masson shifts away from a literal illustration of the mythological story, instead using its themes of violence, sex, and reproduction to suggest more general, cosmic meaning. Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko would build on this modernist approach to classical mythology.

Oil and tempera on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Biography of André Masson

Childhood

André-Aimé-René Masson was born on January 4, 1896 in the small town of Balagny (Oise), north of Paris. He was the eldest of three children in a family of modest means. Growing up in the country, he felt an early connection with nature and the world.

Masson's childhood encouraged unconventional thought. In particular, his mother was a French teacher who promoted unusual texts that would later become important to the Surrealists and were considered scandalous at the time. While his father was more conservative in his beliefs, he did not interfere with Masson's artistic ambitions.

Early Training and Work

Through the efforts of his mother and the quality of his drawings, Masson was admitted to the Brussels Académie des Beaux-Arts at age eleven, which was much younger than usual. He studied under the Belgian painter and sculptor Constant Montald, whose method of mixing glue with water and pigment proved very influential for Masson's later technique. He also took a side job making embroidery designs, which meant his days were filled with study and work.

In his limited free time, Masson read insatiably. He was fascinated by the Quattrocento and the work of the Renaissance masters, along with fin-de-siècle artists like Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. He saw a continuum between the two, remarking when he first James Ensor's Christ in the Midst of the Storm, that "contemporary painting could be as extraordinary as the old masters!"

His interests continued include the modern (he was shocked by Cubism when he first encountered the works of Picasso and Braque) and the traditional (he traveled to northern Italy in 1914 to study fresco painting). Masson also traveled to Switzerland and became fascinated with the philosophical writings of Frederich Nietzsche, which profoundly affected his personal life.

He returned to Paris in 1915 and joined the French army, enduring the violence, trauma and death of World War I trench warfare. He was discharged in 1917 after suffering a severe chest injury; he spent months recovering in military hospitals and spent time in a psychiatric facility. While the experience of being at war was not something Masson often explicitly spoke about, it was the root of the very violent imagery in his work and remained with him for his entire life. After his discharge, he met his wife, Odette Cabalé, and the two relocated to Paris.

Mature Period

In Paris, Masson began making pottery at a studio center for veterans with disabilities. He also took up work with the Journal Officiel. His work from these postwar years featured erotic, sometimes pornographic content that varied widely in style and technique. The founder of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, would later call this Masson's 'erotic period' and believed it to be key to understanding his entire oeuvre.

According to the writer Malcolm Haslam, Masson hosted regular gatherings in his Paris studio at 45 rue Blomet. Here, along with Antonin Artaud, Michel Leiris, Joan Miró, Georges Bataille, Jean Dubuffet, and Georges Malkine, the group experimented with altered states of consciousness, smoking hashish and opium added to wine and music, discussing writers central to the developing Surrealist movement: Nietzsche, Arthur Rimbaud, Comte de Lautréamont, and even the Marquis de Sade.

While vast and divergent in many ways, this group of works shared themes of deep uncertainty and humanity's coexistence with nothingness, ideas drawn from Nietzsche. This philosophy also featured themes of metamorphosis and argued for the changeable nature of organic existence, ideas that would become increasingly important to Masson's art.

In 1921, Masson met fellow artist Joan Miró through their mutual friend, Max Jacobs. Masson and Miró immediately began a friendship that would be influential to both of their careers. The group of artists often met at a studio on the rue Blomet that became a place of intellectual and artistic knowledge, discussion and exploration. Visitors included Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and the playwright Armand Salacrou, who were some of the first buyers of Masson's work.

In 1923, Masson was offered a contract by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a notable art dealer. Although it was not (yet) highly paid, this opportunity allowed Masson to focus solely on his art career. The following years, which encompassed both the Dada movement and the birth of Surrealism, proved some of the most exciting and successful of Masson's career. His style was changeable, and he began to experiment with automatic methods of working, often incorporating motifs from ancient Greek and Roman mythology.

During the 1930s, Masson's work grew increasingly violent and disturbing. His 1930s series of slaughterhouse paintings, built on the art historical legacy of Chaim Soutine's Carcass of Beef (early 1920s) and Rembrandt's Slaughtered Ox (1655), but brought new brutality and sexual associations to the depictions of flesh and meat. It is speculated that this may have been due to his turbulent personal life at the time. Following a 1929 divorce, he met his second wife, Rose, broke with the Surrealist group and moved out of Paris to establish a more solitary life in St-Jean-de-Grasse. He then relocated to Spain, only returning to France in 1936 after witnessing atrocities in the years prior to the Spanish Civil War. Once back in France, he reconciled with Breton and the Surrealists.

In 1941, Masson and his family sought and secured political asylum in the United States, as did many of the Surrealists. Masson's time in America transformed and revitalized his work, introducing new variety in subject matter, style and motifs. He began to focus more on abstractions from nature, alongside his fascination with metamorphosis and cosmic unity. In 1943, Masson underwent his final split from Breton, however he continued to experiment with Surrealism as a style.

Late Period

With the end of World War II, Masson and his family were able to return to France in 1945. During a trip through the south of France, Masson became highly interested in southeastern Asian art and Taoism. His work became increasingly existential, conveying a sense of universal fusion through abstractions of natural landscapes. He remained based in Paris but traveled back and forth to a country house in Aix. In 1965, he was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the Odéon-Théâtre de France and although he was thrilled to complete the project, it proved to be taxing for the aging artist and it was his last major work. This large circular installation, featuring classical figures like Agamemnon and Shakespearean characters like Falstaff, was celebrated as a triumph. The actor Jean-Louis Barrault was said to have declared, "At last we have a sun over our heads." His later career included a series of landscape themes and non-objective paintings. Masson died at his home in Paris in 1987.

The Legacy of André Masson

Masson tackled many of the concepts central to Surrealism and established new ways of representing traditional themes trauma, angst, violence, sex, and death with modern imagery. The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre credited him with "retracing a whole mythology of metamorphoses: (transforming) the domain of the mineral, the domain of the vegetable and the domain of the animal into the domain of the human."

Masson's work influenced numerous 20th-century artists, the most prolific being Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Pollock's Action Painting in particular drew on Masson's experimental use of the automatic technique. Additionally, his use of block coloration and abstraction of form also strongly influenced other artists within the New York School. The practice of automatism has continued to resurface and remains an influence on contemporary art.

Masson's work was also of importance because of its eclectic and multifaceted nature. He experimented with different styles and techniques, so that although he is primarily associated with Surrealism, his work advanced perspectival elements found in Cubism and popularized the use of automatic methods of mark-making that channeled unconscious impulses into visual images. His long career included tremendous range, but featured deeply emotional transparency that allowed viewers to understand the emotional effects of war trauma.

Influences and Connections

-

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Max Ernst]() Max Ernst

Max Ernst ![Friedrich Nietzsche]() Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche- Constant Montald

-

![Joan Miró]() Joan Miró

Joan Miró -

![André Breton]() André Breton

André Breton - Maurice Loutreuil

-

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism -

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism - Automatism

Useful Resources on André Masson

- André MassonOur PickBy William Rubin and Carolyn Lanchner

- André MassonOur PickBy Dawn Ades

- André Masson: The Mythology of NatureOur PickBy Werner Spies, Didier Ottinger and Lucía Ybarra

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI