Summary of Allen Jones

Allen Jones was on the frontline of the 1960s British Pop Art movement. He established himself firstly on the back of a series of brilliantly-coloured semi-abstract paintings, the most successful of which, blended male and female figures. It was at the end of the decade, however, that Jones caused an international sensation with a series of erotic and fetishistic sculptures of women that doubled as furniture items. As the art critic Zoe Williams put it, "Jones wanted to remove sculpture's safety valve - and blew up the 60s as a result". As arresting as his "furniture-sculptures" were (and remain), their notoriety has at times distracted from the fact that Jones has proved himself to be an outstanding painter and printmaker, and an insightful and provocative commentator on the mores of modern morality, especially in respect of attitudes towards fine art and female sexuality. In a career that has spanned six decades, Jones has drawn on visual sources ranging from Orphism, Surrealism, and American Pop Art, while thematically his work has often looked to the worlds of advertising, fashion, dance, and cabaret for inspiration.

Accomplishments

- A contemporary of R. B. Kitaj, David Hockney, Peter Phillips, and Derek Boshier, Jones had a talent for creating flat aesthetic surfaces with and intensity that provoked debate, marked him one of the truly critical Pop artists of his generation.

- Jones remains best known for a set of near life-size sculptures of women in submissive poses, dressed in fetishistic clothing items, and with what Jones called "high definition female parts". The fact that these pieces double as furniture items (a woman on all fours with a sheet of glass on her back passes as a coffee table, for instance) only amplified the "noise" around the figures. Whatever one's view on their content and the artist's intentions, there can be no doubt that Jones had upended expectations of what a sculpture could do.

- Jones stated his position at a time when there was a backlash against figuration, and Minimalism was dominating the contemporary art world. With works such as, Thinking about Women (1961), and The General and His Girl (1961), Jones set in motion something of a personal obsession with finding new ways of representing the human figure. Finding his niche in a "no man's land" between high modernism and popular figuration, Jones produced some of the most surprizing and disquieting works of his generation.

- Jones has explored aspects of form, color, and dimensionality by combining painting and sculpture. In works such as Backdrop (2016-17), a painted pirouetting sculpture, positioned in front of a painted canvas, he found a way to combine his signature use of intense colors, with his love of theater and dance. Indeed, Jones had struck on a way of making color "dance free" from the gallery wall.

The Life of Allen Jones

Art critic Natalie Ferris writes, "[Jones] continues to posit the polarities of gender, exposing the contemporary masquerade of women as objects, women as bodies, women as auras, in contradistinction to that of men, creating artworks that compel their audience to question their own gendered presence. And for Jones, difference is to be celebrated".

Important Art by Allen Jones

Thinking about Women

Thinking about Women is a vibrant and complex composition featuring an assortment of flat shapes and discrete squares. The painting, which utilizes a color palette dominated by bold reds, blues, and browns, creates a dramatic visual impact. The female figures (which are confirmed for the viewer through the title of the work) lack obvious head or facial features, or gender-specific markers such as breasts, hips, or waist. These semi-abstractions, coupled with a small self-portrait at the top of the painting, and an adjacent maze of similar size, hints perhaps at the elusiveness of women. Art critic JJ Charlesworth writes, "Jones's energetic grappling with a cacophony of influences; it's as if the young painter is weighing up the various attractions of American abstract painting against the buzzy possibilities of British Pop. He is staging a battle between high modernism and popular figurative art, and it produces some weird and remarkable results, particularly the puzzle-like, jangling [of] Thinking About Women".

Jones recalled in an interview that at the time he produced the painting "[The] Museum of Modern Art's position on avant-garde 20th Century art was the march from Mondrian to Minimalism. There was the idea that because of [minimalist] Donald Judd, you could not make an image of a figure or a person in the visible world. I could empathize with it but I couldn't get rid of representation". Art historian Marco Livingstone described how Jones would challenge this prejudice (against figuration) in his appraisal of Thinking about Women, and two other canvases, The Artist Thinks (1960), and The General and His Girl (1961), from the same period. He wrote, "Pulling the viewer back and forth from erudite artistic references into popular culture, in the very year[s] in which American Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were making the first comic book paintings, Jones displays the chutzpah that was to become a prime characteristic of the art with which he established his international reputation just a few years later".

Oil on canvas - Royal Academy of Arts, London

Chair, Hatstand, and Table

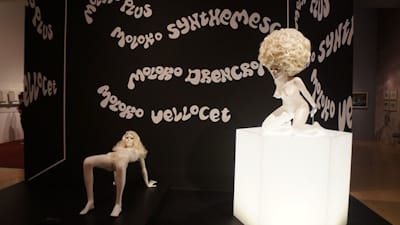

Chair, Hatstand, and Table are Jones's most iconic and infamous works. His near life-sized female mannequins, presented in fetishistic garb and poses, are executed in fiberglass and painted with high-gloss finishes. Chair features a woman kneeling on all fours, serving as the seat of a chair, with her back supporting the sitter. Hatstand presents a standing figure with her arms raised to hold hats. Table depicts a woman on her back with legs raised, supporting a glass tabletop. The sculptures were created from detailed sketches, with Jones closely supervising a professional sculptor to produce the initial clay figurines. The final figures were then cast in plaster by a company specializing in shop mannequins, and thereby ensuring their lifelike appearance. Such would be the uproar around the works, Jones later claimed he found it difficult to exhibit regularly in England.

Given their highly provocative nature, it was of little surprise that the works drew the ire of those who were opposed to the over-sexualization of women in art and culture. The sculptures' notoriety was amplified through their connection to Stanley Kubrick's equally controversial film, A Clockwork Orange (1971). Jones had been approached by Kubrick with a view to use his sculptures as futuristic furniture items for his dystopian film. Jones refused since there would be no fee. The artist recalled how Kubrick (who he had never met) had told him over the phone: "I'm a very famous film director, this [film] will be seen all over the world and your name will be known." Reflecting much later on this short conversation, Jones said, "[I was] just staggered anyone would say that. It showed an ego that dwarfed that of any artist I've known." Nevertheless, Kubrick had near identical pieces made by a set designer (with Jones's consent), although ironically, the assumption amongst many was that the filmed items were original Jones sculptures.

Reactions to the sculptures did not abate with time. A decade after they were first exhibited, for instance, they were pelted with stink bombs by feminists while on display at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. When asked about such reactions, Jones, who has always claimed the sculptures have been misconstrued, remained philosophical, "it's collateral damage", he said, "I wanted to challenge the conventional standards of merit in art. I identified the ideal picture to accomplish this, and it's a coincidence of history that these works came out at the same time as militant feminism". Art critic Johnathan Jones is one of those who defended the works. He wrote, "Allen Jones was a Duchampian before the [Damien] Hirst generation were even born. His art is an icy joke about the power of desire: it pays homage to Duchamp's ironic view of human culture as a masturbatory machine". Writing in 2007, art critic Martin Gayford made a similar point: "Nearly 40 years on, the Table and other pieces look less startling and more part of a tradition that now includes sexualised mannequins by Jeff Koons and the Chapman brothers."

Fiberglass sculpture - Tate, London

Maid to order II

Jones's paintings frequently incorporated subtle sexual innuendo, indicating an interest in men and women's physical relationships, as well as the perceived imbalance between male and female authority. His Maid to Order series is a provocative set of works that represent the artist's exploration of the female form through a stylized, fetishistic, lens. This piece depicts a woman in a tight, form-fitting outfit, exuding a combination of dominance and sensuality. The use of sharp lines and exaggerated curves gives the figure a three-dimensional appearance, while the flat, muted background accentuates the figure's presence. The painting's composition, with its strong contrasts and meticulous attention to detail, highlights Jones's deft handling of visually arresting and conceptually challenging topics.

Maid to Order II was created during a period when Jones was wholly focused on the themes of gender and identity, and using his art to question societal norms and the objectification of women. He said of the works, "They were about personal obsessions. They stood outside the accepted canons of artistic expression, and they suggested new ways of depicting the figure that weren't dressed up for public consumption [...] And even when they appear as a whole, they are bodies separated from reality, bodies born from the collective imagination, bodies born on (magazine) paper that return to paper (or canvas)".

Acrylic on Canvas - Private Collection

The Acrobat

Jones expanded his practice into the realm of public art in 1993 with The Acrobat, a 50-foot-high steel sculpture situated in the atrium of London's Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. The hospital has been hosting a museum-accredited art collection that supports its intensive performative arts programme (including music, dance, theatre, and mime), in its wards and in designated public places within the building, since 1993. The Acrobat was commissioned to mark the opening of the hospital and was at that time thought to be the largest indoor sculpture in the world. The hospital described the idea of commissioning such works as part of an initiative to engender "a more creative and joyful environment for patients, their families and the whole staff".

The Acrobat, an androgenous figure, painted in yellow and teal, balances a large red ball on their extended toe. Jones rendered his figure in flat, interlocking planes, thereby creating a sense of balance, movement, and energy. A non-descript face within a red square at the wooden base, adds a playful and abstract human element. In keeping with the goals of the hospital the sculpture promotes the benefits of performance and physicality. Jones employs his signature techniques, through vibrant shapes and bold colors, to overlap fine art with popular culture; ergo, complexity with simplicity. Described by the hospital as "a landmark sculpture designed to enhance the architecture and provide a focus within a large atrium space", The Acrobat has also been reproduced as an acrylic and plywood limited edition "domestic version", signed and dated by Jones on the underside of its wooden base.

Steel Sculpture - Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London

Whitaker Malem, Leather Sculpture

Earlier in his career, Jones had worked with the leather and rubber worker, John Sutcliffe, who became best known as the creator of the early rubber and leather fetish magazine, AtomAge (subscribers could pay an additional fee to receive its bondage supplement). Jones had first commissioned Sutcliffe to make the boots and the corset for his furniture sculptures. However, following Sutcliffe's death (in 1987) he needed to find new leather artisans and was introduced to Whitaker and Salem, world renowned amongst the fashion and film industries for their meticulous leather craftsmanship. Whitaker said, "we thought it was possible to do a completely leather covered full figure for him, and he said that was an interesting idea and so he got us to do it. Then, it was also shown at the Royal Academy Summer Show, which was quite a big deal, and it was actually shown in a room next to a Degas Ballerina figure, which was wonderful to see. Gary Hume the British artist then bought the sculpture from Allen, and so that was the start of it".

This work features a highly polished, leather-clad figure, viewed from behind, emphasizing the smooth curves and muscularity of the human body. Rendered in rich, dark brown, the figure's sleek and glossy appearance accentuates the figure's contours. The absence of facial features or distinct identity enhances the sculpture's androgenous qualities, making it a compelling representation of the universal human form. Whitaker says, "we've learned more from working with [Jones] than anyone because the process is relatively intimate and personal and he's definitely been the most inspiring. [His] method of working is also comparable with ours. He's deliberate, meticulous, and quite crafted".

Leather

Backdrop

Backdrop is a combination of painting and sculpture that exemplifies Jones's exploration of form, color, and dimensionality. It reflects the artist's preference for bold colors and his fascination with theater and cabaret that have been recurrent themes in his work since the mid-1970s. In fact, the origins of the idea of Backdrop dates back to the 1960s. As he explained in a 2017 interview, "I was living in New York at the Chelsea Hotel, and the French artist Arman, who was also staying there, was working with resins and plastics and doing funny things, and it was intriguing. I suddenly saw there was the possibility of making the color, which is, in a way, imprisoned on the canvas surface, free. I loved the idea that the color could dance free of the wall".

This piece features a female mannequin on a red stool in front of a large, abstract canvas. The mannequin's body is painted so as to blend with the vibrant hues of the canvas, which includes swathes of red, pink, yellow, and green. This technique creates an interplay between the two-dimensional painting and the three-dimensional figure thereby creating a synergy between the painted and physical forms. The mannequin's balletic stance brings a performative element to the work too. In 2019, Backdrop featured in a "multi-generational" group exhibition next to works by Duggie Fields, Jeff Keen, and H.C. Westermann at London's Marlborough Gallery. The gallery announced, "Together, the works establish a snapshot of international Pop, both from its established center and it's richly seeded margins. This provides a glimpse into a broader context and complexity for this generation, and establishes an alternative artistic vein and makes a case for [Pop Art's] ongoing impact".

Mixed media (female mannequin and painted canvas) - Almine Rech Gallery, Paris

Biography of Allen Jones

Childhood

Allen Jones was born in Southampton, Hampshire, in 1937. The Jones family had moved from Wales to the merchant sea-port after his father found work in the docks during the years of the Great Depression. When he was three years old, The Jones' relocated to the London suburb of Ealing where his father worked at a local factory. His mother devoted herself to the role of homemaker. Jones's first memories were of the Ealing Blitz (in September 1940 and May 1941). He attended Ealing County Grammar School for Boys, where his artistic talents were encouraged. His parents had no interest in contemporary art, but they took their son on visits to the Tate Museum. Jones's father sang in an all-male choir, and he remembers fondly that the family home was always alive with the sound of opera music.

Jones also attended an amateur dramatics society with his father. Jones recalled, "I once got a good review in the Middlesex County Times for a play in which I was the villain, and [my father] was the detective. I got my first stage kiss and shot my father in the production". Allen also remembers his father playing the female pantomime character, Widow Twankey. He says, "This was long before Grayson Perry. But dealing with sexual transgression in that way, where it is perfectly clear what the person's gender is, as opposed to drag artists and that world, is an interesting idea. Of course I didn't reflect on it at the time, but there is something in there that links to my work in terms of a robust humour, the stage and artificial presentation".

Early Training and Work

Jones studied painting and lithography at Hornsey College of Art in London between 1955 and 1959. The teaching at Hornsey was based mainly on Paul Klee's "Pedagogical Sketchbook". He also travelled to Provence, Biot and Paris, where he became enamoured with the work of Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger. After Hornsey, Jones continued his education at the Royal College of Art in London. He was in regular contact with other emerging artists such as R. B. Kitaj, David Hockney, Peter Phillips, and Derek Boshier, with whom he would form the next wave of British Pop Artists.

Jones's early paintings presented subjects in a schematic form, liberating his work from the constraints of depicting illusory space. As he progressed, he began to focus more on female figures, rendering them in a stylized three-dimensional, and sensuous manner. However, these changes were not well-received by the Royal College of Art, leading to his expulsion at the end of the 1960 academic year. Jones returned to Hornsey, from where he graduated in 1961. Overcoming his frustrations, he participated in the Young Contemporaries show at the Royal Society of British Artists in 1961, an exhibition widely credited with launching the British Pop Art movement on the international stage. 1961 also saw the beginnings of Jones's long teaching career. (Starting at Croydon College of Art, he would take up Visiting Professor posts in America, Germany and Canada, over a period of more thar 20 years.) Jones's first solo exhibition, held in 1963 at the Arthur Tooth & Sons gallery in London, provided early evidence of his concern with the human body and sexuality. He also participated in Documenta III in Kassel, Germany in 1964.

Jones moved to New York, the home of American Pop Art, in 1964. Art critic Zoe Williams writes, "newly married, [Jones] moved into the Chelsea Hotel, which was rammed with other artists and people giving cello recitals, naked. [Jones said] 'It wasn't group sex or anything, with us. We lived a very correct existence, and my wife [Janet] became pregnant, as it happened, with twins'". Jones, and fellow artist, Peter Phillips, learned from the American Pop artists how to present their art in a more directly, and less ambiguous, way. "American Painting was about the flat surface; in formal terms a Lichtenstein is as flat as an Ellsworth Kelly", he said.

By the end of the decade, Jones was back in London (he put the move down to the practical reason that he couldn't afford private education fees in Manhattan for his twins) where he set up home on the fashionable Kings Road. Jones recalled, "when I returned to the UK after having lived in New York, I found my own voice in the late paintings. The blatant preoccupation with the female figure came to the fore". His painting, Perfect Match (1966), a nine foot semi-abstract topless woman stretched across three canvases, signalled a new direction in his art. The concept was a derivation of the Surrealist idea of the Exquisite Corpse (whereby an accidental image resulted from an image made in separate sections). Jones continues, "During the 60s, the figurative artists in New York, who were working in sculpture, [George] Segal for example, there were echoes of surrealism, so it might be a real bicycle, but the figure was always in plaster. There was always this signal - it might look weird, but it's art. [...] And then I filtered that through my interest in pop culture, in fetish magazines, and memories as a child of going to [the wax works museum] Madame Tussauds". The result was a collection of sculptures that would dominate discussions of his work to this day.

Jones's sculptures featured near life-size female figures in sexually provocative poses. These pieces, which he referred to as "refugees from Surrealism" and like "window mannequins" or "found objects", doubled as furniture items, namely a table, chair, and coat rack. Jones gleaned the idea from an erotic cartoon strip of a figure supporting a tabletop and reasoned - somewhat naively as it turned out - that by attributing a functional element to the sculpture, it would provide a creating distance, or buffer, from any controversy his figures would otherwise provoke. Indeed, many critics argued that Chair, Table, and Hatstand, fell into the old trope of female objectification and perpetuated harmful stereotypes about female passivity. Others, however, defended the works on grounds that his sculptures amounted to critiques, and that by exaggerating and fetishizing his figures, Jones was provoking discussions about gender dynamics and power relationships. While Chair, Table, and Hatstand would rather pigeonhole their creator, they did little to dent Jones's career and his position on the international art scene.

Jones recalled how he had spoken to the legendary director, Stanley Kubrick, on the phone regarding the use of his sculptures in his 1971 movie, A Clockwork Orange (1971). He says, "[Kubrick had] seen an exhibition of mine [featuring Chair, Table, and Hatstand] and he asked if he could use the sculptures in his new movie. I took advice and I was told they'd get trashed. I offered to design something for them, but that didn't work out; basically, he thought I'd do the work for a credit, but no monetary fee. However, I gave him my blessing to use the idea".

Mature Period

In 1970 Jones designed sets and costumes for Kenneth Tynan's scandalous theatrical cabaret, The Empress's New Clothes, Oh Calcutta, which debuted off-Broadway the previous year, before moving to London's West End. The title, a playful pun on the French "O, quel cul tu as" ("O, what an arse you have") caused a storm due mostly to scenes of total nudity. Individual sketches were written by the likes of Samuel Beckett, Sam Shepard and John Lennon. Tynan had also commissioned the British Pop artist, Pauline Boty (its only acknowledged female member) to create a series of paintings of erogenous zones on which the revue would be based. In its review, and while dismissing the revue as "ill-written, juvenile, and attention seeking", The Times wrote, "There is no reason why the public treatment of sex should not be extended to take in not only lyricism and personal emotion but also the rich harvest of bawdy jokes [and that] the stage sets' screen projections assisted the dance numbers considerably".

Jones continued to court controversy. In 1973 he collaborated with photographer Brian Duffy and airbrush artist, Philip Castle, on the "sexist" Pirelli pin-up calendar. Jones designed the promotional poster for Barbet Schroeder's film, Maîtresse (Mistress), in 1975. The film, starring Gérard Depardieu and Bulle Ogier, and featuring the costume designs of Karl Lagerfeld, told the story of sexual obsessive relationship between a petty crook and a dominatrix. Having sat through a preview screening in Paris, Jones said he felt equally "scared to death and enthralled" by the film. The finished film was even refused a certificate for general release by the UK film censors.

While teaching at UCLA, Jones returned to canvas painting using basic shapes with a distinct focus on color. He painted one of his best known pieces from this period, Santa Monica Shores, a view from his apartment overlooking the Pacific Ocean (at Santa Monica), in 1977. Jones's view of the sunset was often obscured by rising sea mists and the picture frame is dominated by Jones's colorful sunset abstraction. At the bottom left of the frame, however, Jones paints the protruding legs (from outside the picture frame) of a seated woman who is taking her own photograph by means of an extension lead connected to the 35mm camera resting on the balcony ledge. In 1978 Jones once again straddled the gap between art, design and commerce when he produced a mural for the luxury Swiss hosiery factory, Fogal, at Basel railway station.

In 1983, Jones took up a one year teaching post (his last) as "Guest Professor" at The University of Arts Berlin. The following year he announced his "Party series" of which he said, "I wanted to celebrate my return to painting with some grand figure compositions [...] what better way to celebrate than having a party!". One such piece, In the Twentieth Century (1986), features a melodious celebration of color and movement and was based on recollections from his early childhood. He said of the work, "As an eight year old at a street party to mark the end of World War II I felt like an outside observer as adults enjoyed themselves and behaved badly around the piano that had been brought out onto the street". In 1986 Jones was elected as a member of the Royal Academy and, in 1990, he was appointed a Trustee of the British Museum (and from 2000 an Emeritus Trustee).

In 2008 Jones returned to his earlier Maîtresse project. His original painting showed a leather-clad brunette in high heels emerging from parted curtains holding a bullwhip. Jones's original was painted on a large canvas with the aim of retaining as much picture detail in the reproduced promotional posters. The film's distributors had been concerned that the artist's image was "too strong" for newspaper advertisements and asked Jones to swap the whip for keys and to change the dominatrix from brunette to blonde. Jones agreed, but reverted to the original design once he had banked his fee. Between 2008-15 Jones went back to the work, creating a further seven Maîtresse canvases. The Michael Wener Gallery said of the collected works, Jones returned to "the dominatrix figure as the means to explore space, form and color. The works share the same deep, fiery palette and overarching symmetrical structure, yet are markedly different in their depiction of light and shadow and the treatment of a figure as both a plane and a volume". Around this time, Jones has also re-embraced sculpture, this time as monumental steel pieces based on intertwining anonymous figures.

In 2014, the art critic Andrew Lambirth wrote, "The price of being controversial is usually increased fame, but for Jones it has resulted in his work being ostracised in this country. Allen Jones is an immensely charming, erudite and sophisticated artist who uses colour, subject and form in inventive and intriguing ways. His career deserves to be properly reassessed". He was writing in response to his retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in 2014. The catalogue featured Jones's iconic photograph of supermodel Kate Moss, bedecked in a metallic body cast he made in 1976. He said of the image, "Photography has replaced the artist's eye in the depiction of reality. For most people Kate exists as a photograph. It is harder to draw somebody than to take their photograph. Painting Kate was a challenge in my world, but first I wanted to prove myself in her world -- the world of professional photography".

Jones has produced a number of public sculptures over his career, including Tango (commissioned for the Liverpool International Garden Festival in 1984); Dancers (Cotton Centre, Hays Lane, Southwark in 1987); Acrobat (Chelsea and Westminster Hospital 1992); and Two to Tango, (Swire Properties, Hong Kong, 1997). His 2019 site specific, Head in the Wind, is situated on London's Greenwich Peninsula. In a 2022 interview Jones said, "The primary thing about the Head in the Wind location is that some people would have to live with it outside their apartment or office window, whereas for the passer-by might catch just a fleeting glance. To have something that would have some meaning from a distance helped establish the work's size. Also, you have to let these pieces go eventually, too. I made a pair of 4m-high works for a street in Hong Kong. At this moment, the developers have pulled the buildings down and they're extending the street. They've contacted me to ask if they can change the colours of the works. It's odd to have these kinds of discussions about something you've worked very hard on; but if they want to paint them yellow, they can paint them yellow. I think the colour change, like the Peninsula, won't violate the piece. Artworks can be a bit like children; they're yours, but they grow up and become their own entities".

Evidence that age had not blunted his verve and ambition came in his exhibition, From the Gods, held at the Almine Rech gallery in Paris in 2024. The collected works, all produced since 2017 - the year Jones turned eighty - carried, in the words of art critic Marco Livingstone, "an air of exuberant defiance". Curator Linnéa Ruiz Mutikainen described the exhibition as a, "clash of contemporary techniques [that] illustrate Jones' continuous cycle of reinvention - oil paintings next to printed works, a photograph ingrained on composite panel, [a] large corten-steel sculpture of a woman with her legs crossed, oscillating between themes of female empowerment and pure desire, [and a] paneled sculpture breathes life into controversy as Jones' fiberglass women-as-furniture make a cameo in the left hand panel, resurrected as robot-like video animations". Livingstone concluded that, "this late flowering displays a youthful vigour, invention and joyful sense of abandon that easily match the trailblazing Pop Art on which Jones staked his reputation and place in art history in the early 1960s".

The Legacy of Allen Jones

Allen Jones was, with Royal Academy peers R. B. Kitaj, Peter Phillips, David Hockney, and Derek Boshier, a key player in the rise of 1960s British Pop Art. His career has seen him move effortlessly between different media - painter, printmaker, designer, photographer, sculptor - and his oeuvre is alive with colorful vitality and imagination that have stayed with him into his ninth decade. And yet the pieces that brought him international fame and notoriety in equal measure have tended to put all his later achievements into the shade. Indeed, few artists in Britain (or elsewhere for that matter) have managed to provoke the level of sustained controversy that Jones has. His provocative sculptures, specifically his iconic furniture works, have shown future generations that by challenging traditional representations of gender, they might encourage a more critical examination of societal constructs. One can see traces of his art, for instance, in the works of artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, both of whom have explored themes of sexuality, consumerism, and the human form.

Reacting to his fetish furniture-sculptures, a 1973 article in the feminist journal Spare Rib by renowned theorist Lura Mulvey suggested that the sculptures were all the evidence one needed of the artist's own "castration complex" (in short, the idea that Jones objectifies and fetishizes women because he fears them). But art historian Norman Rosenthal views his ongoing fascination with cheap eroticism rather as evidence of an art practice where any ethical standards are rendered secondary to the search for "artistic beauty". As Rosenthal put it, "as a revival of Aestheticism " Jones was creating art primarily "for art's own sake". Art critic Daniel Barnes added, "If you shut out that moralising noise, you can see that while Jones makes deliberately provocative work that frustrates interpretation, he always just manages to render his position ambiguous by the fact that the sculptures are more grotesque than anything else. Faced with the shock of the grotesque, it is difficult to know how to take it, but it is certain that Jones' skill for creating an aesthetic surface with sufficient depth to provoke debate makes him one of the few truly critical artists of his generation".

Influences and Connections

-

![David Hockney]() David Hockney

David Hockney -

![R. B. Kitaj]() R. B. Kitaj

R. B. Kitaj - John Sutcliffe

- Peter Phillips

- Derek Boshier

-

![Damien Hirst]() Damien Hirst

Damien Hirst -

![Jeff Koons]() Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons ![Bjarne Melgaard]() Bjarne Melgaard

Bjarne Melgaard![Stanley Kubrick]() Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick- Whitaker Malem

-

![David Hockney]() David Hockney

David Hockney -

![R. B. Kitaj]() R. B. Kitaj

R. B. Kitaj - John Sutcliffe

- Peter Phillips

- Derek Boshier

Useful Resources on Allen Jones

- Allen Jones: ShowtimeOur PickBy Belinda Gardner and Allen Jones

- Allen JonesBy Royal Academy of Arts

- Allen JonesBy Andrew Lambirth

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI