Summary of Alberto Giacometti

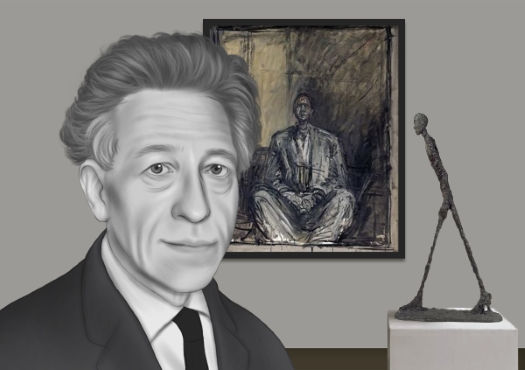

Alberto Giacometti's remarkable career traces the shifting enthusiasms of European art before and after the Second World War. As a Surrealist in the 1930s, he devised innovative sculptural forms, sometimes reminiscent of toys and games. And as an Existentialist after the war, he led the way in creating a style that summed up the philosophy's interests in perception, alienation and anxiety. Although his output extends into painting and drawing, the Swiss-born and Paris-based artist is most famous for his sculpture. And he is perhaps best remembered for his figurative work, which helped make the motif of the suffering human figure a popular symbol of post-war trauma.

Accomplishments

- Giacometti's work of the 1930s represents probably the most important contribution to Surrealist sculpture. In an effort to explore themes derived from Freudian psychoanalysis, like sexuality, obsession and trauma, he developed a variety of different sculptural objects. Some were influenced by primitive art, but perhaps most striking were those that resemble games, toys, and architectural models. They almost encourage the viewer to physically interact with them, an idea which was very radical at the time.

- In the late 1930s, Giacometti abandoned abstraction and Surrealism, becoming more interested in how to represent the human figure in a convincing illusion of real space. He wanted to depict figures in such a way as to capture a palpable sense of spatial distance, so that we, as viewers, might share in the artist's own sense of distance from his model, or from the encounter that inspired the work. The solution he arrived at involved whittling the figures down to the slenderest proportions.

- Giacometti's post-war achievement - finding a language through which to represent the figure in real space - impressed the many writers of the period who were interested in Phenomenology and Existentialism. Both of these philosophies contained ideas about self-consciousness and how we relate to other human beings, and Giacometti's art was thought to powerfully capture the tone of melancholy, alienation and loneliness that these ideas suggested.

- Although the 1950s art world of both Europe and the United States was dominated by abstract painting, Giacometti's figurative sculpture came to be a hugely influential model of how the human figure might return to art. His figures represented human beings alone in the world, turned in on themselves and failing to communicate with their fellows, despite their overwhelming desire to reach out.

The Life of Alberto Giacometti

Calling it “a complete transformation of reality,” Giacometti was struck by a vision after leaving a cinema in Paris. Trembling with fear, he entered a familiar café and was met by a waiter, “his eyes fixed in an absolute immobility.” Subsequently, he began sculpting the tall emaciated figures with prominent heads that evoked the existential angst of the post World War II era.

Important Art by Alberto Giacometti

Gazing Head

In his early years, Giacometti often experienced difficulty in sculpting from life. In this despair, he began to work from memory. The early plaster bust Gazing Head, arguably the artist's first truly original work, illustrates the culmination of this effort. The flatness of the head and face - Giacometti's economical placement of smooth divots for definition - result in a bust that is at once abstract and figurative. And yet the underlying theme of the work, the act of gazing, invites viewers to ponder whether what they are looking at is in fact a mirror. When Gazing Head was first exhibited in Paris in 1929, it immediately grabbed the attention of the French Surrealists, beginning an association that would cement the early part of Giacometti's career.

Plaster - Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung, Zurich

Suspended Ball

Although works like Gazing Head caught the attention of the Surrealists, it was Suspended Ball, first exhibited at Galerie Pierre in 1930, that prompted André Breton to invite Giacometti to join the group. The sculpture's white globular form - at once floating freely and trapped in a cage - and the enigmatic segment below it, all evinced the dream-like and erotic qualities that the Surrealists adored. In fact, following the 1930 group exhibition, Salvador Dalí contributed an article on Surrealist objects for Breton's periodical, inspired by Suspended Ball. Despite this association with Breton's group, critics have also associated the sculpture with the ideas of Breton's rival, Georges Bataille. It has been argued that the elements in the sculpture are deliberately enigmatic, since while they seem to suggest a sexual act, it is unclear which element is male and which female. This confusion of categories has been said to encapsulate Bataille's notion of informe, or formlessness.

Metal, cord, plaster - Fondation Giacometti, Paris

Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object)

Hands Holding the Void illustrates how Giacometti started to stray from the Surrealists after his brief association with the group. It was created as a monument to the artist's recently deceased father, embracing what the critic Carl Einstein called a "metaphysical realism." It incorporates certain primitive and Egyptian elements. The void the figure is holding is possibly the soul, or what the Egyptians called kâ. While the Surrealists embraced this work, the figurative elements indicate that the artist was beginning to move beyond them.

Bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

City Square

The multi-figured City Square, while not Giacometti's first foray into the waif-like figures for which he is best known, is a stunning exercise in creating an impression of spacious landscape. Treading amidst an empty space, the figures - what Sartre called "moving outlines" - seem to rise out of nothing. In a 1960 review for The Nation, Fairfield Porter observed, "Giacometti's concern is to place the relationship of man and landscape with the ground. And he further considers man and everything else as having a dual relationship to the environment as a link between the earth and infinity." By this time Giacometti was well acquainted with Existentialism, and City Square could be interpreted along its lines, depicting as it does mankind as a mere shadow of itself, existing half-way between being and nothingness.

Painted bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Annette with Chariot

Although sculpture is the medium for which Giacometti is best known, he was also an accomplished painter and draughtsman. This 1950 oil work shows his skill at creating an impression of profound depth on a flat surface. The subject here is the artist's wife Annette, who is composed of the same lines and strokes used to depict the surrounding room, as if she herself were just another object. Nevertheless, like Giacometti's sculptural stick figures, Annette does subtly emerge from the composition, asserting her humanity amidst the otherwise bland order of the room. Much as some of the leading Existentialist thinkers of the time noted, Giacometti's mature work was an antidote to abstraction.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

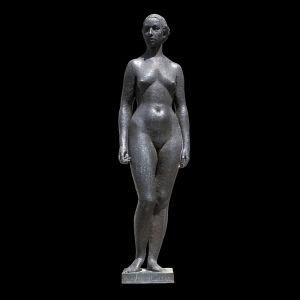

Woman of Venice II

Perhaps no other writer has better summed up Giacometti's bronze stick figures than Francis Ponge, who wrote in a 1951 article for Cahiers d'Art, "Man - and man alone - reduced to a thread - in the dilapidation and misery of the world - who searches for himself - starting from nothing... Man on a pavement like burning iron; who cannot lift his heavy feet." Like other works in this vein, Woman of Venice II shows a single figure, her body seemingly beaten almost to the point of disintegration, yet still standing tall and upright. At the heart of such works was the theme of human dignity and mankind's need to assert its existence in a vast universe that seems bent on its destruction.

Bronze - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Biography of Alberto Giacometti

Childhood

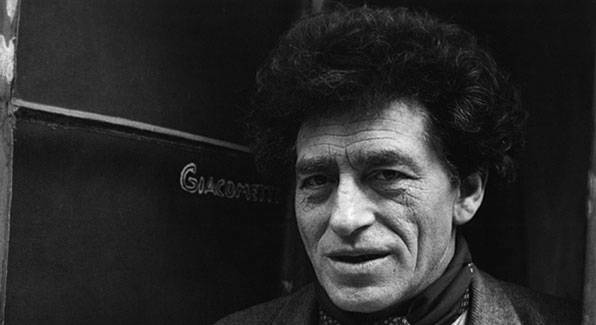

Alberto Giacometti was born in 1901 in the mountain hamlet of Borgonovo, in eastern Switzerland. He was the first of four children born to Giovanni Giacometti, a Post-Impressionist painter, and Annetta Giacometti-Stampa, whose family was among the area's prominent land owners. In addition to his father, several members of Giacometti's extended family were artists, including Augusto Giacometti (second cousin to both Giovanni and Annetta), who was a Symbolist painter, and Cuno Amiet, Alberto's godfather and a close family friend, who was a Fauvist.

When Giacometti was no older than ten, he began to send pencil and crayon drawings to his godfather Amiet, most of which he saved and survive today. And in the years that followed, he began to experiment with oils and still lifes, often using his siblings as models. He produced his first painting at age twelve.

Early Training

In 1915, Giacometti enrolled at the Evangelical School in the town of Schiers, where he continued to work in a small private studio. Later he enrolled at the École des Arts Industriels in Geneva, and studied painting, drawing and sculpture under the tutelage of Pointillist painter David Estoppey and sculptor Maurice Sarkissoff.

In May 1920, Giacometti traveled to Italy with his father, where he viewed paintings by Jacopo Tintoretto at the Venice Biennale, Giotto's frescoes in Padua, and ancient Egyptian art at the Archeological Museum in Florence. Soon after, he moved to Paris, where he enrolled in several art classes, and later he began to be attracted to Cubism and primitive art. In 1926 he exhibited his very first major bronze sculpture work, the idol-like Spoon Woman (1926-27), at the Salon des Tuileries.

Mature Period

By the 1930s, Giacometti had been warmly welcomed into Surrealist circles, and he became close to figures such as Man Ray, Joan Miró, André Masson and Max Ernst, as well as the movement's founders André Breton and Louis Aragon. But he also published work in Documents, the periodical produced by writer Georges Bataille, who was then putting forward a version of Surrealism in opposition to Breton's. Critics now believe that Bataille's ideas may have been important in inspiring several of Giacometti's Surrealist works, such as Suspended Ball (1930-1).

In June 1940 Giacometti and his brother Diego fled Paris by bicycle, narrowly missing an encounter with the invading German Wehrmacht (the next day they witnessed the city's bombardment from afar). Giacometti remained in France during this time, and forged friendships with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, thinkers who would later influence his figurative work.

In 1946, following the liberation of Paris, and Giacometti's own three-year hiatus in Geneva, he returned to the French capital. That same year his former lover, Annette Arm, joined him, and the two were married in 1949. Arm modeled for him on several occasions, including for the oil painting Annette with Chariot (1950). It was while living in Paris during these years that Giacometti arrived at his mature style of elongated figures, reportedly after spending time sketching passersby in the city streets.

Late Period

As Giacometti's style continued to mature into the 1950s and 60s, his bronze figures grew larger and more complex, ranging from his Woman of Venice II (1956) at nearly four feet tall, to Tall Woman II (1960), towering at close to nine feet. He also devoted more time to portraiture, in both painting and sculpture. His regular models included Diego and Annette, as well as Isaku Yanaihara, a Japanese philosophy professor and writer whom he befriended in 1955.

By the 1960s, Giacometti was internationally famous, but his health declined. He was plagued by heart and circulatory problems. Nevertheless he continued to work, and in his final weeks he was working on a bust and painting of Elie Lotar, a French photographer and close friend. On the evening of January 11, 1966, he died of complications of pericarditis.

The Legacy of Alberto Giacometti

Both of the important phases of Giacometti's career yielded innovations that influenced a wide range of artists. His Surrealist sculpture of the 1930s, for instance, influenced Henry Moore, partly inspiring the Surrealism that would be such an important component of Moore's practice throughout his life. It is certainly hard to imagine Moore's own innovative experiments in the 1930s without Giacometti's example. And Giacometti's figurative work was vital in re-establishing the figure as a viable motif in the post-war period, at a time when abstract art dominated. His spindly bronze figures, which appear punctured and fragile, compressed in space, are in many respects visual manifestations of Existentialist thought, emblems of the condition of modern humanity ravaged by doubt.

Influences and Connections

-

![André Masson]() André Masson

André Masson -

![Louis Aragon]() Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon -

![Balthus]() Balthus

Balthus -

![Max Ernst]() Max Ernst

Max Ernst ![Georges Bataille]() Georges Bataille

Georges Bataille

-

![Eduardo Paolozzi]() Eduardo Paolozzi

Eduardo Paolozzi -

![Alexander Calder]() Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder ![Jean-Paul Sartre]() Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre![Jean Genet]() Jean Genet

Jean Genet![Francis Ponge]() Francis Ponge

Francis Ponge

Useful Resources on Alberto Giacometti

- A Giacometti PortraitOur PickBy James Lord

- In Giacometti's StudioBy Michael Peppiatt

- Giacometti (2009)By Ulf Kuster, Pierre-Emanuel Martin-Vivier

- Alberto Giacometti: Face to FaceBy Christian Alandete

- Alberto Giacometti: A BiographyOur PickBy Catherine Grenier

- Alberto Giacometti: Retrospective (2010)By Donat Rutiman, Thierry Dufrene, Nadia Schneider, Alberto Giacometti

- Alberto Giacometti: Works, Writings, Interviews (Essentials Poligrafa) (2007)Our PickBy Angel Gonzalez, Alberto Giacometti

- Alberto Giacometti (2002)By Felix Baumann, Christian Klemm, Alberto Giacometti

- Alberto GiacomettiBy Yves Bonnefoy

- Alberto Giacometti: A Retrospective Exhibition (1974)By Ulf Kuster, Pierre-Emanuel Martin-Vivier

- GiacomettiOur PickBy Karole Vail and Megan Fontanell

- Alberto Giacometti: Sculptures, Paintings, DrawingsOur PickBy Angela Schneider