Summary of Transcendental Painting Group

The Transcendental Painting Group (TPG), formed in New Mexico in 1938, was a band of artists determined to break free from ordinary reality. Instead of painting the visible world, they conjured visions of inner light, cosmic order, and divine harmony. Against the backdrop of vast desert skies and adobe-dotted landscapes, their canvases glowed with radiant geometry, pulsing colors, and forms that seemed to breathe. They weren't chasing trends, they were chasing transcendence, believing that art could transport both creator and viewer into realms beyond material life.

What made them progressive wasn't just their rejection of realism, but their fearless blending of modernist abstraction with mystical traditions. Drawing heavily from Theosophy, symbolism, and the rhythms of nature itself, TPG artists turned painting into a vehicle for meditation and spiritual ascent. In the midst of the Depression and looming war, they offered a radical alternative: luminous windows into peace, unity, and higher consciousness. Their short-lived experiment left an outsized mark, seeding ideas that would ripple through later generations of abstract and spiritual art.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The TPG, through its co-founder Raymond Jonson, introduced "absolute painting" to America; paintings built entirely from color, light, space, and form without reference to the visible world. This advanced non-objective art as a spiritual practice and emerged years before Abstract Expressionism popularized pure abstraction.

- By locating avant-garde experimentation in New Mexico, the TPG expanded the centers of American modernism beyond New York and Europe.

- The TPG bridged cultures and philosophies. Their work fused Indigenous aesthetics, Eastern mysticism, and Western esotericism into a uniquely American language of abstraction.

- The group's published manifesto was one of the clearest early American calls for abstraction as a spiritual language, positioning art as a path to "imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual."

- The TPG's luminous abstractions laid groundwork for Color Field painters like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman and foreshadowed the Light and Space movement of the 1960s-70s, inspiring artists who sought to evoke spiritual presence through color, geometry, and light.

Overview of Transcendental Painting Group

Shrouded in mystery and the occult, the Transcendental Painting Group significantly altered the landscape of modern American art history, highlighting the global fascination with Theosophy among 20th-century avant-garde artists.

Artworks and Artists of Transcendental Painting Group

Oil No. 6 (Crystal)

Oil No. 6 (Crystal) features an array of crystalline shapes rendered in translucent hues of blue, green, and purple, creating a sense of depth and spatial complexity. The sharp edges and overlapping facets of the crystals draw the viewer's eye into the composition. Jonson's use of gradients and shading within the crystals enhances their three-dimensionality, making them appear almost tangible despite their abstract nature.

Throughout his career, co-founder of the Transcendental Painting Group Raymond Jonson (1891-1982) pursued a quasi-mystical goal of achieving visual harmony through what he termed the "unifying principle" of design. He believed that a successful painting should encapsulate his emotional, intellectual, and physical experiences while exhibiting high craftsmanship. Instinct and intuition were crucial to his creative process, and he maintained that this ideal could only be realized through abstraction.

This work is significant because it embodies the core aims of the TPG to use abstraction as a pathway to the spiritual and transcendent. The painting's crystalline geometry and radiant light effects reflect Jonson's commitment to Theosophical and mystical ideas, particularly the notion that hidden spiritual structures underlie material reality. By reducing form to luminous planes and faceted shapes, Jonson sought to evoke the clarity and order of higher consciousness, aligning with the pursuit of "non-objective" art as a visual language for transcendence.

Oil on canvas - The University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque

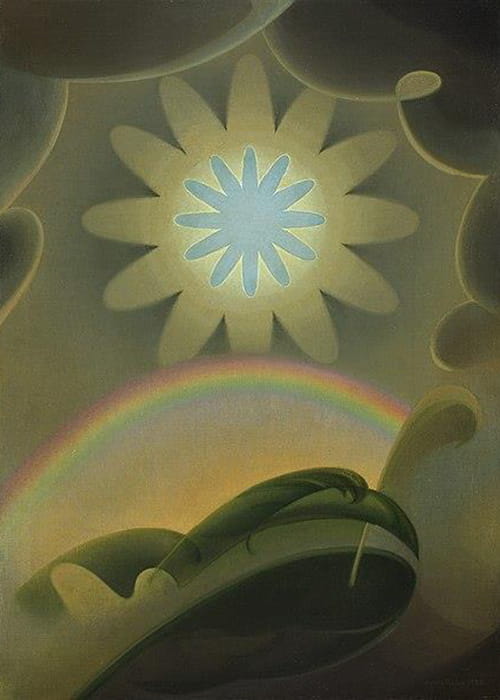

Sand Storm

Sand Storm is characterized by a central, radiant flower-like form composed of overlapping, softly glowing petals that emanate from a bright blue center. Below this celestial bloom, a delicate rainbow arches over an abstract landscape of fluid, organic shapes in shades of green and yellow. The background is enveloped in a hazy atmosphere, with subtle gradients of dark and light that enhance the painting's dreamlike quality. This painting reflects the "abstract beauty of the inner vision, which would be kindled by the inspiration of these rare and solitary places" Agnes Pelton (1881-1961) found in the desert.

Pelton was an American modernist painter who played a crucial role in the development of transcendental abstraction. Born in Germany to American parents, she briefly lived in Switzerland before moving to the United States. She graduated from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. In 1910, she studied life drawing at the British Academy of Arts in Rome and exhibited in the Armory Show by 1913. She first visited the Southwest in 1919, staying at writer Mabel Dodge Luhan's home in Taos. She traveled extensively in the 1920s, creating abstract paintings of earth and light, and settled in Cathedral City, California, by 1932.

Pelton's early work was influenced by the Symbolist movement and the teachings of Theosophy. Due to her esoteric interests, Pelton was invited to join the TPG. Pelton's paintings often feature luminous, abstract forms that evoke a sense of otherworldliness and spiritual introspection. Over time, Pelton shifted from abstractions to painting desert landscapes for income, known as a "desert transcendentalist." Her work is characterized by metaphysical landscapes with biomorphic compositions, delicate veils, shimmering stars, and atmospheric horizon lines.

Oil on canvas - Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville

Abstract Painting #98

Abstract Painting #98 exemplifies the abstract style of Lawren Harris, characterized by the use of bold geometric forms and a harmonious color palette. The painting features a dynamic composition of intersecting planes and lines, creating a sense of movement and depth. Harris employs a restricted yet impactful color scheme; the precision of the geometric shapes and the clarity of the lines reflect Harris's meticulous approach to composition, emphasizing balance and harmony within the abstract forms.

Lawren Harris (1885-1970) was a notable Canadian painter and active member of the Theosophical Society founded by Blavatsky. Harris spent three years studying in Germany from 1904 to 1907, where he developed an interest in Theosophy. Coming from a wealthy family allowed him to fully dedicate himself to his art. Harris became a leading landscape painter, infusing his works with a profound spiritual dimension. He spent the years 1938-1940 in New Mexico, where he shifted to abstract art and incorporated Canadian nationalist themes. Harris was also a member of the Group of Seven, a collective of Canadian landscape painters considered Canada's first major national art movement.

Harris developed from a rebellious nationalist reading of the northern landscape to a universal view of the spiritual power of nature. This evolution eventually led him to a clinical and analytical approach to abstraction, influenced by Theosophy and Transcendentalism. Harris once said, "It seems that the top of the continent is a source of spiritual flow that will ever shed clarity into the growing race of America."

Oil on canvas

Frame 12, Second Movement, (the Crystal) from The Spiral Symphony

Frame 12, Second Movement, (the Crystal) from The Spiral Symphony (1938) is a striking example of Horace Towner Pierce's (1912-1958) watercolor mastery, where geometric precision and delicate handling of pigment converge. The composition is built around a progression of concentric, nested squares, each layer shifting in color from deep blue at the outer edge to a glowing green at the center. This chromatic transition creates both depth and rhythm, drawing the viewer's gaze inward as though being pulled into a meditative core. Cutting across this ordered sequence is a finely rendered pink spiral, a soft yet dynamic line that introduces movement and disrupts the rigid geometry with a sense of organic vitality. The painting is simultaneously mathematical and poetic, precise yet dreamlike.

This work embodies the union of geometry, mysticism, and musicality that the collective sought to express. The title situates the work in dialogue with music, a metaphor frequently used by the TPG to describe the spiritual resonance of abstraction. The concentric squares echo mathematical order and dynamic symmetry, while the spiral references timeless symbols of growth, energy, and transcendence. By merging these elements through the luminous medium of watercolor, Pierce crafted a visual experience meant to guide the viewer toward contemplation of unseen realities. In doing so, the painting stands as a clear manifestation of the Group's manifesto: to move painting beyond mere representation and into the realm of the spiritual imagination.

Pierce was born in Meeker, Colorado. He grew up in a household with a Quaker stepmother and a highly intelligent father, a research chemist who suffered from significant hearing loss. He moved to Baltimore in 1925 and attended the Maryland Institute of Art. In 1936, Pierce traveled to Taos to study under Bisttram, who taught meditation-inspired painting at his Taos Art School. He was described as "one of Bisttram's young idealistic students." Pierce spent the early part of his career in New Mexico as an early member of the Transcendental Painting Group.

Watercolor on paper - University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque

Watercolor #6

Watercolor #6 is an exemplary piece showcasing the fluidity and dynamism of watercolor as a medium. The brushstrokes vary from delicate and fine to bold and sweeping, creating a sense of movement and spontaneity. The composition, which might depict a landscape, is both balanced and chaotic, with areas of dense pigment juxtaposed against lighter, more translucent washes.

William Lumpkins (1909-2000) was a central figure in the TPG and the only member of the group who was raised in New Mexico. His distinctive personal style was emblematic of New Mexican culture, a unique blend of Indigenous, Hispanic, and Anglo-American influences. He was a man with charisma, known for wearing a broad-brimmed Stetson hat, Mexican-style cowboy boots, and a neck scarf. Additionally, he was a trailblazer in passive solar architecture, designing many buildings to absorb and radiate heat from the sun effectively. Some examples of his architectural contributions that have become landmarks in Santa Fe include Rancho Encantado, First Northern Plaza, DeVargas Center, as well as portions of the Inn at Loretto and sections of La Fonda. This heritage permeates the tonal essence and spatial sensibility of the piece - even as it stretches into ethereal territories. Though abstract, the work may hint at a physical environment or cosmic terrain with subtle echoes of the artist's native land yet elevated into the transcendent realm.

Lumpkins began exhibiting his watercolor paintings in 1932 and was an early adopter of Abstract Expressionism, using the style nearly a decade before it became popular among other American artists. From 1938 to 1942, he exhibited alongside Raymond Jonson and other members of the Transcendental Painting Group.

Watercolor on paper - Private collection

Abstraction

This painting exemplifies the abstract style of TPG co-founder Emil Bisttram (1895-1976), characterized by the careful arrangement of geometric shapes and a sophisticated use of color. Rectangles, circles, and lines interact in a balanced composition, animated by a predominantly cool palette. Layered shapes generate depth and movement, while subtle tonal shifts and textures reveal the artist's meticulous technique and sensitivity to visual harmony.

Guided by a belief that art could express universal truths and spiritual experience, Bisttram used precise geometry and balance as tools for contemplation, inviting viewers into a meditative encounter with form and color that transcended the material world. His fascination with philosophy and mathematics led him to adopt the theory of Dynamic Symmetry, a system based on the golden ratio, which he believed unlocked the hidden order of nature. His commitment to numerology was so intense that he changed his name from Bistran to Bisttram, partly influenced by a numerologist and partly because the double "t" resembled the Greek letter pi, an emblem of infinite proportion and mathematical perfection.

Created during a period of global conflict (World War II), Abstraction reflects the TPG's effort to assert timeless, spiritual values in the face of uncertainty. Between 1936 and 1947, Bisttram also produced a series of encaustic abstractions inspired by Hopi Indian art, working with heated beeswax and pigment on paper. He intended them to be meditation tools and mystical objects whose aim was to realign spiritual forces in anticipation of the advent of the New Age. He never sold the works during his lifetime, showing them only to close friends.

Gouache on cream wove paper - Private Collection

Rising Red

Created in 1942, Rising Red showcases Florence Miller Pierce's (1918-2007) aptitude for combining geometric abstraction with a sense of ethereal transcendence. The painting features a composition dominated by a large, pale blue circle that seemingly floats against a soft, gradient background transitioning from light blue to white. Within this circle, a thin black ellipse adds a sense of dimensionality and depth. The use of color and form conveys a sense of harmony and balance, while the interplay between the red and blue tones evokes a feeling of spiritual ascent.

Florence Miller Pierce was born in Washington, D.C., in 1918. She traveled to New Mexico at the age of eighteen to stay with her grandparents and study under Bisttram. Two years later, she returned to Taos and joined the TPG in the late 1930s. Miller is the youngest member and one of only two women (the other is Agnes Pelton) in the circle. She eventually married fellow member Horace Towner Pierce.

After her husband's death, Miller adopted the name Pierce and took a hiatus from art. She once said that her works "are contemplative. They're about stilling the mind." Miller had met Theosophists Auriel Bessemer and his wife, who had studied under Annie Besant, a student of Theosophical Society co-founder Helena Blavatsky. This encounter introduced Miller to ideas she would later explore with the TPG. Rising Red reflects these theosophical concepts: red symbolizes vitality and life force, while the circle and ellipse signify wholeness and spiritual unfolding. By placing these elemental forms within a luminous, meditative field, Pierce transformed color and geometry into vehicles of transcendence, using abstraction to evoke unseen spiritual realities and invite inner stillness.

Oil on canvas - The McNay Museum Collection

Beginnings of Transcendental Painting Group

By the 1930s, many artists were turning away from representational art toward abstraction as a means of accessing inner and spiritual realities. Influenced by avant-garde figures such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, and by broader modernist beliefs that art could reveal higher truths, artists increasingly rejected realism as an adequate language for meaning. Theosophy and related esoteric philosophies provided an alternative framework, emphasizing hidden wisdom, cosmic order, and the unity of all life - ideas that profoundly shaped the symbolic language of abstraction during the interwar period.

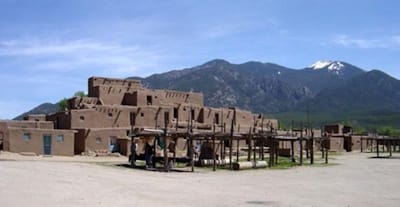

At the same time, the American Southwest - particularly New Mexico - had become a powerful destination for artists and spiritual seekers disillusioned by the aftermath of World War I and the failures of industrial modernity. The desert's vastness, silence, and distinctive light, combined with the region's ancient Indigenous presence and distance from urban centers, fostered a sense of timelessness and spiritual possibility. This perception intensified during the Great Depression, as economic collapse and institutional failure pushed artists to seek meaning beyond political or material systems. For those drawn to abstraction, the Southwest functioned as a liminal landscape where inner and outer realities seemed to converge, allowing painting to operate as a meditative and metaphysical practice. It was within this cultural, spiritual, and geographic context that the Transcendental Painting Group emerged, framing abstraction as a moral and spiritual response to a fractured world.

Founders and Formation

Friends Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram, both steeped in modernist ideas, envisioned an American creative presence that could channel abstraction into a spiritual mission.

Raymond Jonson was born to a Swedish Baptist minister in Lucas County, Iowa., where he grew up immersed in an environment that emphasized inner moral life, discipline, sacrifice, and spiritual striving. This early exposure left an imprint, and his later writings would echo the Protestant valuation of inward experience, even as he rejected doctrinal belief.

Jonson always aspired to be an artist and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. He was profoundly influenced by the avant-garde works in the city's 1913 Armory Show, which introduced American audiences to European modernism including Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism through works by artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. Jonson's work often depicted lines of energy rippling across the picture space. His forms sometimes appeared as animated Art Deco architectural details, suggesting a transfiguration of matter into something beyond the physical. Jonson once wrote, "We never enjoy or appreciate those things we can have without any effort or strong sacrifice. For myself, I would gladly sacrifice all physical for one perfect complete existence of spiritual emotion."

Jonson and his wife relocated to Santa Fe in 1924 to escape the challenges of modern urban life, remaining residents of New Mexico for the rest of their days. In the 1930s, Jonson increasingly explored pure abstraction, culminating in a stylistic breakthrough in 1938 influenced by his study of the works of Kandinsky and László Moholy-Nagy. Jonson termed his purely abstract works in oil, watercolor, and casein tempera - many created with airbrushes - as "absolute painting."

Emil Bisttram was born near the Hungarian Romanian border, emigrated to the U.S. with his parents, and grew up in New York's Lower East Side. Bisttram received an extensive art education, studying at the National Academy of Design, Cooper Union, Parsons School of Design, and the Art Students League. Bisttram first visited Taos in the summer of 1930 and fell in love with the landscape, prompting him to move there. In 1931, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to study mural painting, which allowed him to travel to Mexico and learn from Diego Rivera. During the Great Depression, Bisttram completed several federally funded mural projects. Upon Bisttram's return to Taos in 1932, he established the Heptagon Gallery and the Taos School of Art, where he emphasized rigorous training in composition and color theory. Bisttram required his students to engage with Transcendentalism and Theosophy, incorporating readings from Emerson, Nietzsche, Jung, and Kandinsky's Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

Bisttram met Jonson in the early 1930s through mutual involvement in regional art activities. They shared philosophical and spiritual interests, and both followed in the footsteps of an earlier generation of painters, particularly those which had been involved in the Taos Society of Artists. The Society, which disbanded in 1927, helped establish the Southwest as a major center of American art through representational depictions of Indigenous life, Hispanic culture, and the regional landscape. It played a foundational role in shaping early Southwestern Regionalism and attracting later generations of artists to Taos, even as its realist approach would eventually be challenged by modernist and abstract movements.

Jonson and Bisttram's collaboration and shared desire to lift human consciousness through art directly sparked the formal creation of the Transcendental Painting Group (TPG) in 1938. The collective was established in Santa Fe and Taos where the New Mexico light, vastness, and stark landscape provided a natural stage for visionary art. The cities had already become havens for artists seeking inspiration outside the European canon such as Georgia O'Keeffe. For the TPG, the Southwest offered a setting that felt both ancient and otherworldly, aligning with their desire to go beyond material reality.

The group's core members included William Lumpkins, Agnes Pelton, Lawren Harris, Florence Miller Pierce, Horace Pierce, Robert Gribbroek, Stuart Walker, and Ed Garman. While most were based in New Mexico, Pelton resided in Southern California. The membership of Dane Rudhyar and Alfred Morang remains contested: Rudhyar adopted the TPG's modernist style later than its inception, and Morang was connected to its formation, though sources differ on his formal inclusion.

Objective and Manifesto

The Transcendental Painting Group sought to develop and promote a purely abstract style infused with spiritual meaning. Rooted in a search for the transcendent, their work blended biomorphic and geometric forms illuminated by ethereal light, with compositions that echoed the innovations of Constructivism and the Bauhaus. Inspired by Kandinsky's non-objective experiments and the wider currents of American modernism, TPG artists aimed to evoke sensory, synthetic experiences of nature and the cosmos, often drawing on music, esoteric philosophies, and symbolic references to the American landscape. During the turmoil of the Great Depression and the approach of global war, their radiant paintings attempted to move beyond material existence - using color, space, light, and design to express universal truths and reveal the eternal.

The TPG's purpose and goals were clearly outlined in their manifesto, which was published and distributed in a brochure in 1938:

"The Transcendental Painting Group is composed of artists who are concerned with the development and presentation of various types of non-representational painting, painting that finds its source in the creative imagination and does not depend upon the objective approach.

The word Transcendental has been chosen as a name for the group because it best expresses its aim, which is to carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world, through new concepts of space, color, light and design, to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual. The work does not concern itself with political, economic, or other social problems.

Methods may vary. Some approach their plastic problems by a scientific balancing of the elements involved; other(sic) rely upon the initial emotion produced by the creative urge itself; still others are impelled by a metaphysical motivation. Doubtless as the group grows other methods will appear.

The Transcendental Painting Group is no coterie, no accidental group of friends. The members are convinced that focal points in terms of group activity are necessary in order to present an art transcending the objective and expressing the cultural development of our time. The main activity of the Group will be arranging exhibitions of work. The goal is to make known the nature of transcending painting which, developed in its various phases, will serve to widen the horizon of art."

The members of the TPG did not adhere to a common or unified style, nor did they try to create one. However, their works exhibit broad stylistic and symbolic similarities stemming from their shared philosophical and spiritual beliefs, goals for abstraction, and familiarity with each other's works. They resisted the narrative demands and moral judgments of regionalism by maintaining their focus on non-objective painting. TPG also rejected the need for validation from other artists, especially those with a narrowly Eurocentric view of the avant-garde, which may have limited their wider recognition.

Theosophical Influence

An integral part of the Transcendental Painting Group was a shared engagement with occult philosophy, mysticism, and, most centrally, Theosophy. Rather than a fixed doctrine, Theosophy offered a flexible spiritual framework grounded in the belief that a universal, underlying reality connects all life, matter, and consciousness. It privileged inner knowledge over religious dogma and proposed that spiritual truth could be accessed through intuition, meditation, and heightened perception.

These ideas were shaped in large part by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, who founded the Theosophical Society in 1875 and articulated an eclectic philosophy drawing from Hinduism, Buddhism, ancient Greek thought, and modern scientific inquiry. Blavatsky's writings proposed that art, science, and spirituality were not separate pursuits but interconnected paths toward the same universal truth.

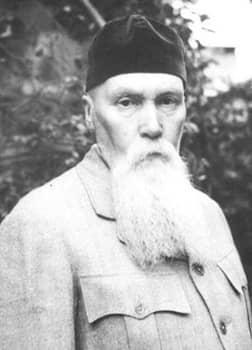

Another influential figure was Nicholas Roerich, a Russian painter, writer, and theosophist deeply inspired by Theosophy and Buddhism. He had a vital impact on TPG's leader, Raymond Jonson. In 1921, Jonson met Roerich, whose spiritual and artistic concepts left a lasting impression on him. Roerich believed in the unity of all religions and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment through art. His paintings often depicted mystical landscapes, sacred symbols, and historical events. Roerich conveyed to Jonson the belief that painting, theater, dance, and music were all expressions of a unified spiritual truth underlying all experiences. Together, they founded the Chicago group Cor Ardens (Flaming Heart), based on the idea that the collective arts served as a "universal medium of expression and proof of existence."

Theosophy absorbed and synthesized various ideas from European and Eastern Mysticism and symbolic lore, emphasizing the individual's right to choose their own path to truth, free from dogma and tradition. Although Theosophy was later marginalized with the rise of empirical science and rationalism, it significantly influenced early twentieth-century artists and writers.

Exhibitions and Reception

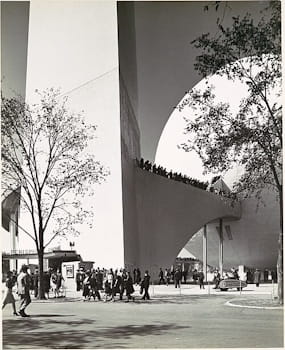

The TPG experienced several notable successes during its initial three years. By 1939, the group had displayed their work at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. This event provided a platform for the TPG artists to present their works to a broader audience. Later that year, some members exhibited at the New York World's Fair. They also showcased their art at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York City (now called the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum).

These early exhibitions received mixed responses. While they were appreciated in some circles, they struggled to gain widespread recognition due to the dominance of other art movements. At the time social realism and homespun Americana was being championed by Regionalism, and the Ashcan School was a central art movement in the United States focused on creating works that depicted everyday life scenes in New York City, particularly in its poorer neighborhoods. Conventional historical accounts suggest that it was only after the Second World War that American artists fully accepted the avant-garde movement. However, these conventional narratives are increasingly seen as narrow due to the existence of the TPG.

Concepts and Styles

Esoteric Philosophies

Esoteric philosophies formed a foundational framework for the Transcendental Painting Group, shaping both their conceptual aims and their formal language. Central among these influences was Theosophy, a spiritual philosophy that proposed the existence of an underlying, universal reality connecting all life, matter, and consciousness. Rather than functioning as a rigid doctrine, Theosophy offered artists a way to reconcile spirituality, philosophy, and modern scientific thought, encouraging the belief that invisible forces - light, vibration, energy, and cosmic order - could be apprehended through heightened perception and expressed visually through abstraction. This perspective positioned art not as representation of the external world, but as a conduit to inner and transcendent realities.

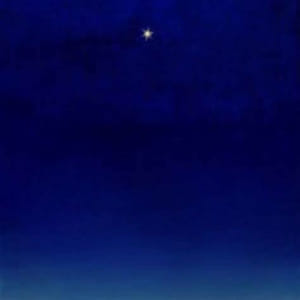

Agnes Pelton exemplified this approach through luminous, introspective abstractions that translated inner vision into visual form. Works such as Star Gazer reflect her engagement with meditation, Theosophical writings, and intuitive perception, presenting painting as a means of spiritual revelation. Pelton viewed her works as vehicles for metaphysical truth, often describing them as visual equivalents of prayer, anticipating later developments in American spiritual abstraction. Her practice underscored the group's belief that painting could function as a meditative experience for both artist and viewer.

The TPG's engagement with Theosophy also positioned them within broader transnational currents. In the late twentieth century, scholars Eduardo Devés Valdés and Ricardo Melgar Bao would describe "Theosophical networks" that linked artists, intellectuals, and political thinkers across the Americas during the interwar period. The formation of the Transcendental Painting Group in New Mexico has since been recognized as a key node within this network, facilitating the exchange of ideas related to reincarnation, karma, cosmic evolution, and the synthesis of Indigenous, Mesoamerican, and Eastern spiritual traditions with modern abstraction.

Occultism further informed the group's approach, particularly through its emphasis on hidden knowledge and universal laws underlying physical reality. Long a source of artistic inspiration, from Renaissance art to Symbolism, occult philosophy reemerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as artists sought spiritual meaning amid industrialization and global conflict. Emil Bisttram was deeply engaged with occult and Theosophical thought, believing that art could embody universal principles through formal harmony. He employed systems such as dynamic symmetry and symbolic geometry to structure his abstractions, linking mathematical proportion with spiritual truth. His painting Oversoul (1938-41) reflects this synthesis, visualizing a divine essence that unites all beings through radiant, ordered form.

Mysticism provided yet another dimension, emphasizing direct, personal experience of transcendence rather than initiation into secret knowledge. For the TPG artists, mysticism offered a path beyond materialism and social ideology, aligning painting with meditation and inner ascent. Their shared interest in Eastern religions, Native American spirituality, and Western esoteric traditions was unified by a belief in mystical union - the possibility of accessing ultimate reality through disciplined inward awareness. Pelton, often called the "desert transcendentalist," embodied this approach, using abstraction to convey experiences of inner light and divine presence.

Spiritualism also shaped the group's thinking, particularly its emphasis on communication with unseen realms. While often dismissed as irrational, spiritualism played a significant role in modernist culture by linking artistic creation to psychic and immaterial forces. For the TPG, this belief reinforced the idea that art itself could function as a medium of channeling energies, consciousness, or spiritual presence into visible form. Florence Miller Pierce's work exemplifies this influence. Her use of light, geometry, and later resin reliefs sought to embody immaterial forces, creating works that feel less like images than transmissions, or portals through which viewers encounter states of stillness and expanded awareness.

Together, these esoteric philosophies provided the Transcendental Painting Group with a coherent spiritual and intellectual foundation. They enabled the artists to reconceive abstraction as a means of transcendence, positioning painting as a disciplined, contemplative practice capable of revealing unseen dimensions of reality. In doing so, the TPG aligned themselves with a broader lineage of "occult modernism," extending currents explored by artists such as Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Hilma af Klint into the unique spiritual and geographic context of the American Southwest.

New Mexico and Native American Traditions

The TPG's emergence in a landscape saturated with Indigenous art, architecture, and spiritual traditions had a profound impact on their philosophies and creativity. The region's pueblos, petroglyphs, ceremonial dances, and symbolic designs offered a living repository of visual abstraction and spiritual expression. Native American art provided a precedent for art as a vehicle for transcendence rather than representation. The abstraction of geometric pottery designs, the symbolic use of color, and the integration of art with ritual life resonated with the group's own desire to create works that transcended the material world and spoke to universal truths. Rather than imitating motifs directly, TPG members absorbed the underlying principles: rhythm, harmony, and an intimate connection between art, place, and spirituality.

William Lumpkins, the only native New Mexican TPG member, embodied this influence more directly than many of his peers. Having grown up immersed in the Southwest, he was particularly attuned to Indigenous traditions and their relationship to land and spirit. His watercolors of the 1930s and 1940s often echo the flat planes and organic geometry found in pueblo pottery and Navajo sand painting, while his sense of space reflects the open expanses of the desert landscape. For example, in works like Watercolor #6 (1939), his use of layered, translucent forms and rhythmic, almost ceremonial arrangements of shape suggest a dialogue with Native cosmologies and their vision of interconnected forces. Later, as an architect, Lumpkins also carried forward Indigenous building traditions through his pioneering of passive-solar adobe design. In both painting and architecture, he translated Native American ideas of harmony with nature and spirituality into modernist abstraction, exemplifying how the TPG's goals intersected with the cultural and artistic heritage of the Southwest.

Non-Objective Abstraction

The TPG embraced non-objective, or pure, abstraction as the foundation of their artistic practice, rejecting representational imagery in favor of paintings constructed entirely from color, light, line, geometry, and spatial relationships, an approach Raymond Jonson described as "absolute painting." Exemplifying this is Jonson's work Composition, c. (1940), in which the composition is constructed entirely from interlocking planes of color and light, with no reference to the visible world.

For the group, non-objectivity was not a stylistic departure but a philosophical necessity. By abandoning narrative imagery and culturally specific symbols, TPG artists sought to access inner vision and universal spiritual truths that they believed lay beyond the visible world. Abstraction allowed them to move past surface appearances and to treat painting as a moral and metaphysical act, capable of engaging higher states of consciousness rather than depicting external reality.

This commitment positioned the group as early innovators of American abstraction. Years before Abstract Expressionism came to define non-objective art in the United States, the TPG demonstrated that abstraction could function as a serious spiritual and philosophical language. Their work challenges the dominant narrative that situates the origins of American abstraction exclusively in postwar New York, expanding the canon to include a parallel, spiritually driven modernism rooted in the American Southwest.

Light as Primary Subject

For the TPG, light functioned not simply as a means of illumination but as a primary substance of the painting itself; radiant, vibrating, and often structuring the entire composition. Forms appear to glow from within, hover in indeterminate space, or emanate energy, dissolving the traditional distinction between figure and ground. Rather than describing light as it falls upon objects, TPG artists treated luminosity as an active presence, shaping space and perception through color and radiance.

Agnes Pelton's Evening Star (1939) exemplifies this approach, treating light not as depiction but as an organizing spiritual force. A luminous central form radiates outward against a quiet, atmospheric field, producing a sense of suspended stillness and inward expansion. The painting does not represent a celestial body so much as evoke a state of consciousness, with light functioning as presence, guidance, and inner awakening. This understanding of light was deeply informed by Theosophical thought and the lived experience of the desert, where intense clarity and vast openness heightened awareness of light as both physical and spiritual force. For the group, light symbolized consciousness, life energy, and transcendence, operating as a metaphysical principle rather than an optical effect.

Geometry and Dynamic Order

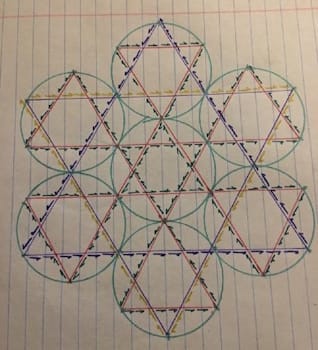

Geometry and dynamic order played a central role in the visual language of the TPG as its artists frequently employed circles, spirals, grids, crystalline forms, and carefully balanced planes of color structured through proportion and rhythmic harmony. Informed in some cases by mathematical systems such as dynamic symmetry, these geometric frameworks were not pursued as exercises in rational design but as expressions of universal order. For the TPG, geometry functioned as a spiritual language, evidence of hidden laws underlying physical reality, and a means of visualizing cosmic balance during a period marked by economic collapse, political instability, and global conflict. Horace Towner Pierce's Frame 12, Second Movement (The Crystal) from The Spiral Symphony (1938) exemplifies this approach: concentric geometric forms and a dynamic spiral organize the composition with musical precision, guiding the viewer inward through carefully modulated color and rhythm. Rather than operating as cold formalism, Pierce's geometry evokes metaphysical ascent and inner harmony. By framing geometry as a vehicle for transcendence rather than a mechanical device, the TPG expanded the expressive possibilities of abstraction and contributed to a broader understanding of geometric modernism as emotionally resonant, spiritually charged, and deeply human.

Color as Vibration and Consciousness

For the TPG, color functioned as vibration and consciousness rather than as a descriptive or naturalistic element. Applied in translucent layers, subtle gradations, and luminous palettes, color was understood to suggest movement, energy, and inner states of being. Influenced by Theosophical color theory and the writings of Wassily Kandinsky, TPG artists believed that color carried emotional and spiritual resonance capable of affecting the viewer directly, bypassing narrative and intellect in favor of felt, perceptual experience. Agnes Pelton's Fires of Spring (1939) exemplifies this approach through its use of radiant, ascending color fields that unfold within an atmospheric space, evoking spiritual awakening and inner transformation rather than a literal scene. In Pelton's hands, color became an animating force, an expression of life energy and consciousness itself, embodying the group's belief that abstraction could transmit metaphysical experience through purely visual means. By treating color as a vibrational language rather than ornament or symbol, the TPG expanded the expressive potential of abstraction and helped lay the groundwork for later color-based and phenomenological approaches to painting that emphasize immersion, perception, and spiritual resonance.

Later Developments - After Transcendental Painting Group

The Transcendental Painting Group existed as an active collective for only a brief period. By 1942, its activities had largely ceased, the result of depleted funds, the dispersal of members during World War II, Agnes Pelton's residence in California, the sudden death of Stuart Walker in 1940, and a gradual waning of collective momentum. Yet the group's short lifespan belies the depth and reach of its influence. Working outside dominant artistic centers and institutional frameworks, the TPG developed a spiritually driven abstraction that would resonate long after the group itself dissolved.

The group's legacy is most evident in the evolution of postwar abstraction. Its emphasis on light, color, and inner experience anticipated the concerns of Abstract Expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, whose color field paintings similarly sought to evoke transcendence through non-objective form. Florence Miller Pierce's later resin works extended these ideas into three dimensions, prefiguring the Light and Space movement of the 1960s and 1970s and foreshadowing the perceptual investigations of artists like James Turrell and Robert Irwin. By situating advanced abstraction in the American Southwest rather than New York or Europe, the TPG also expanded the geographic narrative of modernism, demonstrating that experimental, spiritually motivated art could emerge from alternative cultural and environmental contexts. Their synthesis of esoteric philosophy with Indigenous and Mesoamerican spiritual concepts further laid groundwork for later cross-cultural modernist practices.

Contemporary scholarship increasingly positions the Transcendental Painting Group within a broader global history of "occult modernism," alongside figures such as Hilma af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky. Their work continues to inform contemporary artists - including Anish Kapoor, Julie Mehretu, Loie Hollowell, Zoe McGuire, Joani Tremblay, and Alicia Adamerovich - who draw on abstraction to explore metaphysical, philosophical, and experiential dimensions of perception. These artists inherit the TPG's conviction that non-objective form can function as a conduit for meaning beyond representation.

Although largely overlooked for decades, the group's work reentered public consciousness beginning in the late twentieth century, when renewed curatorial and scholarly attention brought their paintings back into exhibitions and museum collections. Since that time, continued research and exhibition efforts have secured the TPG's place within the broader narrative of American modernism. Beginning in the 1990s and culminating in the Whitney Museum's 2020 exhibition Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist, Pelton has been celebrated as a major figure in the painter's canon.

In retrospect, the Transcendental Painting Group occupies a crucial position in the history of abstraction: not as a peripheral curiosity, but as an early, sustained experiment in spiritual modernism. Their commitment to non-objectivity, metaphysical inquiry, and artistic independence offers an alternative genealogy of American abstraction - one rooted in contemplation rather than spectacle, and in transcendence rather than ideology.

Useful Resources on Transcendental Painting Group

- Another World: The Transcendental Painting GroupOur PickBy Michael Duncan, Malin Wilson Powell, et al.

- Vision and Spirit The Transcendental Painting GroupOur PickBy Tiska & Ed Garman Blankenship

- The Transcendental Painting Group: New Mexico, 1938-1941By James & Anne Glusker Monte

- The Occult Sciences - A Compendium of Transcendental Doctrine and ExperimentBy Arthur Edward Waite

- The Art of the Occult: A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern MysticBy S. Elizabeth

- Haunted Visions: Spiritualism and American ArtBy Charles Colbert

- Concerning the Spiritual in Art PaperbackBy Wassily Kandinsky

- Alchemy & MysticismBy Alexander Roob

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI