Summary of Theosophy and Art

Theosophy is an occult belief system with its origins in the late nineteenth century, which draws on many world religions and proposes that reality as we understand it is an illusion, with a truer version of reality lurking behind the veil of appearances. These ideas have been extremely influential on a whole swath of modern art, from the minimalist abstraction of Piet Mondrian to visionary Outsider art of the present day. Although not all of this art is directly rooted in Theosophy - which is connected specifically with the mystic and intellectual Helena Blavatsky and her acolytes - the ideas associated with the movement seeped into the collective consciousness of the art-world to such an extent that the indirect or ambient influence of Theosophy is truly vast. In the broadest terms, art influenced by Theosophy tends to involve abstraction, and the use of precise and often unusual systems of visual symbolism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Theosophy proposes a world of spirit or emotion separate to the world of matter, one that we can gesture towards through visual symbols and motifs. A similar idea is central to Abstraction, one of the underpinning characteristics of much painting and sculpture since the late nineteenth century. It's no surprise, then, that many pioneers of abstraction such as Wassily Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint, and Piet Mondrian, were heavily influenced by theosophical ideas.

- The principles of Theosophy allowed art to retain its spiritual significance into an era when traditional religious beliefs and the representational role of art were being eroded in tandem. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, the vast majority of art had been realistic, and was intended to record, reflect, or strengthen faith. Theosophy proposed a new kind of spiritual truth which had to be gestured towards through non-representation and arcane symbolism. This perfectly suited the emerging mood of modern art.

- The belief systems of individual Theosophists and Theosophically influenced artists are many and varied, but they all tend to propose defined systems of visual symbolism. Specific shapes, colors, and patterns are associated with particular ideas, emotions, or principles. Some symbols with widespread usage in Theosophy found their way into the art-world at large, so that the symbolism of modern art is directly and indirectly influenced by the symbolism of Theosophy.

- Theosophy combined elements of many world religions and philosophies to create a wholly new belief system. In this sense, it reflected an increasingly globalized world and was a harbinger of the culture of the twentieth century, with its ever-increasing levels of dialogue, exchange, and intermingling between different ethnic and national groups, and its greater tolerance of diversity and difference. Theosophy was also the forerunner of the New Age movements of the 1960s, which was partly connected to the Outsider Artist movement.

Overview of Theosophy and Art

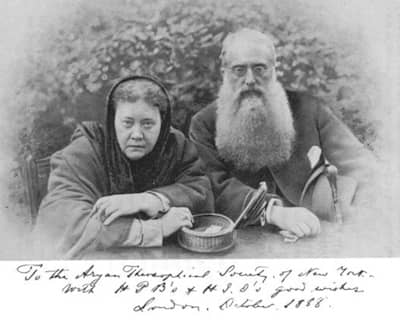

Theosophy is rooted in the ideas of its charismatic and eccentric founder, Madame Helena Blavatsky, a Russian aristocrat and émigré who cut a swath through the intellectual and artistic circles of the Western world at the close of the nineteenth century and inspired many followers and acolytes.

The Important Artists and Works of Theosophy and Art

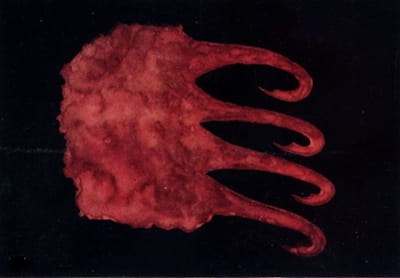

The Gamblers (Figure 32 from Thought-Forms)

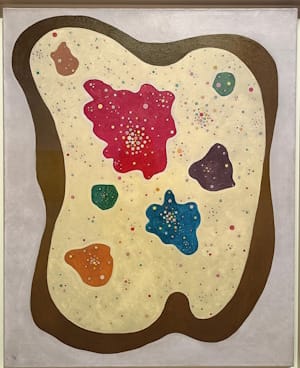

In 1901, the Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater published Thought-Forms, a book that reproduced several watercolor paintings supposedly representing ideas, emotions, and character types, accompanied by written analysis. In her foreword, Besant wrote: "it is our earnest hope - as it is our belief - that this little book will serve as a striking moral lesson to every reader, making him realise the nature and power of his thoughts, acting as a stimulus to the noble, a curb on the base." Besant and Leadbeater note that "we have often heard it said that thoughts are things....Yet very few of us have any clear idea as to what kind of thing a thought is, and the object of this little book is to help us to conceive this." They warn, however, that two-dimensional representations can never truly capture the reality of a thought-form as they exist in three dimensions. Furthermore, "the vast majority of those who look at the picture...have not the slightest conception of that inner world to which thought-forms belong, with all its splendid light and colour."

Unlike much abstract art, the thought-forms of Besant and Leadbeater are associated with a specific symbolic system. The book includes a table showing "the meanings of colors," for instance, with light blue representing "High Spirituality" and black symbolizing "Malice". They also outline three key principles determining the appearance of thought forms. "1. Quality of thought determines colour. 2. Nature of thought determines form. 3. Definiteness of thought determines clearness of outline." The "thought-forms" in the book include emotions such as "devotion," "sacrifice," "anger," "jealousy," and "ambition." The authors also illustrate psychological and emotional responses to musical stimuli, as well as more complex thoughts like "greed for alcohol," "grasping animal affection," and "at a shipwreck," "at a funeral".

Describing The Gamblers, Besant and Leadbeater stated that "the forms shown...were observed simultaneously at the great gambling-house at Monte Carlo...they represent the feelings of the successful and the unsuccessful gambler respectively." Of the lower form, they note "the background of the whole thought is an irregular cloud of deep depression, heavily marked by the dull brown-grey of selfishness and the livid hue of fear. In the centre we find a clearly-marked scarlet ring showing deep anger and resentment at the hostility of fate". Meanwhile, "the upper form represents a state of mind which is perhaps even more harmful in its effects, for this is the gloating of the successful gambler over his ill-gotten gain. Here the outline is perfectly definite, and the man's resolution to persist in his evil course is unmistakable."

Watercolor on paper

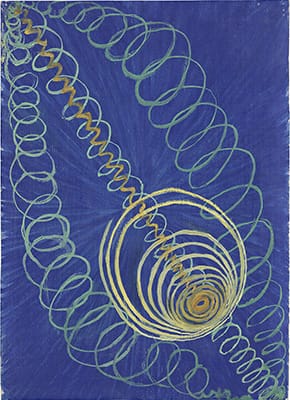

Primordial Chaos - No 16 (from The Paintings for the Temple)

Born in 1862, the Swedish painter Hilma af Klint became interested in spiritualism, occultism, and mysticism at the age of 17, in particular Theosophy and Rosicrucianism (an occult movement which had much in common with Theosophy). In 1879, she began attending séances run by the Swedish artist and medium Bertha Valerius, and the following year, after the death of her younger sister Hermina, she became more involved in the séances, hoping to be able to contact her sister's spirit. By the mid-1890s, she and four other women (Anna Cassel, Sigrid Hedman, and sisters Mathilda Nilsson and Cornelia Cederberg) had formed a group they called De Fem ("The Five"), which met regularly to engage in automatic drawing and writing. They also held séances during which they would supposedly transcribe messages from mystic beings called "High Masters". These encounters and experiences led af Klint to work in a more abstract style, as compared to the figurative academic style in which she was trained. By the late 1890s, she was representing several Theosophical concepts in her art, including the idea that communion with nature could offer spiritual awakening. Af Klint joined the Stockholm Lodge of the Theosophical Society on May 23, 1904, though she would later follow into the Anthroposophical Society, which she joined in 1920..

In 1905 or 1906, during a séance, af Klint had a transformative experience and claimed that a High Master named Amaliel gave her the mission (or what she called the "commission") of creating a body of work that would act as a gateway into unseen realms. The resultant series, titled Paintings for the Temple, was produced during 1906-15. The artist claimed that the sequence of 193 works was guided by Amaliel, stating: "the pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke." Art critic and writer Julia Voss concluded after reading af Klint's notebooks that "she was in dialogue with these forces, they were more like friends than an authority".

The earliest works in the Paintings for the Temple series are known as the Primordial Chaos sub-group. This group of 26 small paintings represents the origins of the world and the Theosophical idea that, as critic Stefanie Graf puts it, "everything was one at the beginning but was fragmented into dualistic forces." Many works in this group feature snail-shell or spiral forms, intended to represent evolution and development. These concepts are central to many aspects of Theosophy, including the Theosophist belief in the reincarnation and gradual spiritual ascendency of the soul. Curator Tracey Bashkoff says of Primordial Chaos - No 16, "the work deals with ideas of dualities. This was a large part of Theosophical teaching and thought that Hilma af Klint was engaged in. One idea that was teased out in Theosophy was the idea of there being a oneness at the beginning of the world, and that that oneness was then shattered, and that life is a pursuit of the bringing together of the opposite forces that were torn apart at the beginning of creation. And that is also tied to sort of a search for a closeness to divinity. And so we see the tumultuous beginning of things, where there's a spiraling form of energy that then sort of comes apart". For af Klint, as for many artists inspired by Theosophy, color also held symbolic significance, for instance here with blue representing the feminine, and yellow representing the male.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

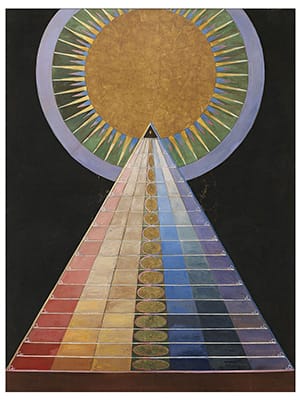

Altarpiece No. 1 Group X

The culmination of Hilma af Klint's Paintings for the Temple series was the Altarpieces, a triptych created for the innermost sanctum of the imaginary "spiral temple" that she hoped would house the entire series. The notes for this work from the Art Gallery of New South Wales refer to the "use of metallic leaf, which gives them a special, luminous quality." Altarpiece No. 1 Group X features a triangle divided into a grid, with each row painted in one of the colors of the rainbow, from red on the left to violet on the right. Behind the apex of the triangle is a large golden circle emanating blue and yellow rays, enclosed in a violet circle. Here we find some of the most foundational forms in Theosophical thought including the triangle (a symbol of ascension) and the circle (a symbol of the divine or spiritual realm).

Af Klint divided the Paintings for the Temple series into groupings based on themes such as electromagnetic waves, the ideas of her friend and mentor Rudolf Steiner, and the connection between nature (plants and animals) and metaphysical realm. Artist and writer Rosie Lasso notes that, across the series, "Klint painted in a surprisingly diverse range of scales, sizes and themes, producing an extraordinary body of work that merged abstract geometric and biomorphic forms, a private, coded symbolism, and brilliantly bold colours that hum and vibrate with sonorous musicality. Klint envisioned one day showcasing her series in a spiral temple, taking viewers on an intoxicating journey higher and higher towards heaven." Af Klint's work on the series continued well past the disbanding of The Five - the all-female automatic writing and drawing group she had founded in the late nineteenth century - in 1908.

Af Klint died in 1944, and stipulated in her will that her paintings and notebooks should not be made publicly available for at least 20 years (she believed that by that point the world would be more prepared to embrace the spiritual message of her work). In fact, her work was only rediscovered in the 1980s, and scholarly attempts to understand it continue to this day. Marco Pasi, Professor in the History of Hermetic Philosophy, writes that "whereas it had been possible for some critics and art historians to minimise the extent of the influence of Theosophy on other early representatives of abstract or non¬mimetic art, such as Kandinsky and Mondrian, things were different with af Klint. Given that her work was 'discovered' more recently, it has always been clear that esoteric ideas were crucial in her artistic output." Years after the series' completion, the artist described Paintings for the Temple as "the one great task I carried out in my lifetime."

Le Rêve (The Dream)

A Czech abstract artist and pioneer of Orphism, František Kupka was deeply influenced by Theosophy, particularly the writings of Blavatsky, Besant, Leadbeater, and Steiner. He also drew inspiration from Eastern religions and philosophies, as well as other forms of spiritualism and occultism. However, as art historian Tessel M. Bauduin notes, Kupka "did not become a Theosophist, nor did he embrace all the tenets of Theosophy". Rather, he was "drawn to certain elements that resembled and expanded upon his personal mystical world view", in particular the idea of "astral vision and the astral world." Kupka's arts education in the early 1890s in Prague and Vienna focused in large part on sacred painting and allegorical and symbolic subjects. He believed strongly in the Theosophical principle that, behind the world we see and experience, lie other "hidden", immaterial realities. He once stated "The creative ability of an artist is manifested only if he succeeds in transforming the natural phenomena into 'another reality.'"

The critic Phillip Barcio notes that Kupka's "first foray" into proto-Theosophical principles involved "paint[ing] symbolist images, in which allegory and metaphor were employed to suggest a world of meaning beyond what was obvious in the picture. But soon he sought a greater freedom, from "the expectations and assumptions of the figurative world" as such. Sometime in the late 1890s, Kupka relocated to France, settling in the outskirts of Paris. There, he formed connections with other avant-garde artists interested in abstraction, like Robert and Sonia Delaunay (with whom he developed Orphism), Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, Francis Picabia, and Juan Gris. This loosely-connected group became known as the Section d'Or - a group that led the development of Salon Cubism. In 1923, Kupka published his book Creation in the Plastic Arts (though he had finished writing it in 1913), devoting much of the book to theories of color and its relationship with emotion and music.

The influence of Theosophy can be seen in many of Kupka's works, such as The Dream (1909). Bauduin explains that "Kupka became interested in theories concerning vibration, radiation, and the emission of waves; scientific themes that were very popular in occult and Theosophical circles at the time". He was also interested in the "Theosophical idea that nature manifests itself rhythmically in geometric forms". This "Theosophical syncretic vision of science and the spiritual coincided with Steiner's vision of the unity of science, art and religions. It determined the subject matter of Kupka's art: the dynamic process of the universe." In The Dream, two small nude human figures (one male, one female) lie on the floor of a dark room painted with deep, dreamy blues and purples. On the tall wall to the left, two larger, semi-transparent, overlapping, nude figures (again, male and female) appear to float in a beam of green-blue light, in a sensual embrace. Evidently, they are projections (or more accurately, the astral projections) of the figures on the floor. At the lower left of the image is an inscription from Kupka to his lover and future wife Eugénie ("Ninie") Straub, which reads "My dear Ninie, Here I sketch the dream that I had of the two of us - Yours, Franc."

Oil on cardboard - Kunstmuseum Bochum, Germany

Evolution

The Dutch painter Piet Mondrian is best-known as a founder of De Stijl, a movement created in 1917 based on his theories of Neoplasticism (minimalist geometrical abstraction). He was a dedicated Theosophist, joining the Dutch Theosophical Society in 1909 and living for a time at the movement's headquarters in Paris when he moved there in 1911. Upon relocating to England at the outbreak of World War Two in 1938, Mondrian transferred his membership to the English Theosophical Society. In 1944, when he died in New York, his few possessions included a Theosophical Society membership card and several books on Theosophy. Mondrian was also in regular contact with the Anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner, from whom he drew ideas and inspiration.

Indeed, Mondrian was concerned with Theosophical principles even before his turn to the famous, radical abstraction of De Stijl, when he still identified as a Symbolist. The monumental triptych Evolution (1910-11), according to art historians Charles Cramer and Kim Grant, "shows the 'three spirits' that Madame Blavatsky described as living within humankind: terrestrial (on the left), sidereal or astral (on the right), and divine (in the center)." The art historian Robert P. Welsh takes the yellow color used in the center and right-hand panels to represent the astral "shells or radiations" of those two figures, and that the relationship between the figures from left to right indicates development "from matter through soul to spirit." Fred Wilson sums up the work by stating that "these images of a rigid but also not-quite-material, not-quite-human, being seem to provide a means to attain to a world of beings lacking physical reality."

This piece can, in fact, be taken as one of various examples where Mondrian's work represents particular passages from Blavatsky's writing. In Isis Unveiled (1877), Blavatsky states that "three spirits live and actuate man [...]; three worlds pour their beams upon him; but all three only as the image and echo of one and the same all-constructing and uniting principle of production. The first is the spirit of the elements (terrestrial body and vital force in its brute condition); the second, the spirit of the stars (sidereal or astral body - the soul); the third is the Divine spirit." Cramer and Grant note that Evolution shows "Mondrian's interest in finding a visual language for expressing spiritual things, [though it is] far from the radical abstraction that he later arrived at." As Wilson puts it, "Mondrian himself came explicitly to reject art that embodies symbols of the sort that one finds in the triptych."

Oil on canvas - Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Netherlands

Composition with Great Blue Plane

Mondrian's involvement with the Theosophical Society had a profound influence on the development of De Stijl and Neo-Plasticism. Indeed, Theosophy was at the center of his entire worldview, and he believed it would one day replace religion. "Through Theosophy", the artist stated, "I became aware that art could provide a transition to the finer regions, which I will call the spiritual realm." He was particularly influenced by theosophist author Édouard Schuré's 1889 book The Great Initiates: A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Similarly important was the Theosophist mathematician M. H. J. Schoenmakers's 1915 book Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld (The New Worldview). In this book, Schoenmaker asserted that truth, beauty, and "the inner structure of reality" (or "pure reality") could be best understood through complementary relationships like inner and outer, masculine and feminine, and vertical and horizontal.

Art historian Fred Wilson argues that "Mondrian was involved in a genuine philosophical search for a way to express the vision of Ultimate Reality and Meaning that he had found in the Theosophists, but which he developed in his own way. The rather trivial and indeed nonsensical geometrical and numerological lore upon which the founders of the movement proposed to rely, he found to be lacking. He discovered that the means that they provided were inadequate to the ends they proposed." Wilson even boldly asserts that "Mondrian had a more adequate understanding of the structure of the metaphysical framework concerning Ultimate Reality and Meaning than did the theosophists."

The artist came to believe that a highly simplified form of geometrical abstraction could serve as the ideal means for representing cosmic harmony, order, and balance. The results of this can be found in works such as Mondrian's 1921 painting Composition with Great Blue Plane. To this end, he championed utilizing only black, white, and what Schoenmakers called "the three essential colors" of red, blue, and yellow. He also reduced the use of line in his work to exact horizontals and verticals, because, as Schoenmakers insisted, "the two fundamental and absolute oppositions that shape our planet are: the horizontal line of the earth's trajectory around the Sun, and the vertical trajectory of the rays that emanate from the center of the sun." Overall, Mondrian emphasized harmonious, balanced compositions, writing that "the equilibrium of any particular aspect of nature rests on the equivalence of its opposites. [...] The tragic is created by unequivalence".

Oil on canvas - Dallas Museum of Art

Einige Kreise (Several Circles)

Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky was a pioneer of Abstraction in Modern art. He was also heavily influenced by Theosophy, particularly the texts of Steiner, Blavatsky, Besant, Leadbeater, and Schuré. Kandinsky and Rudolph Steiner were active in Munich around the same time and Kandinsky attended several of Steiner's lectures. He was also an avid reader of Steiner's theosophical Theosophical journal, Luzifer-Gnosis. Though he never formally joined a theosophical Theosophical society or referred to himself as a Theosophist, the influence of Theosophy can be seen in the development of Kandinsky's art in his seminal theoretical text Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art) (1912). This text speaks of a "spiritual revolution," and a "spiritual food" of a "newly awakened spiritual life," which no longer has a "material objective," but rather seeks "internal truth." Linguist and Theosophist John Algeo explains that "Kandinsky's theory of abstract art - that the realism of surface appearances is misleading - is the artistic correlate of the Theosophical doctrine of maya - that the world of perception is an impermanent illusion in comparison with the underlying noumenon."

Kandinsky's art took from Theosophy the idea that abstract symbols could convey spiritual messages. He also felt that visual art should aspire to the condition of music in its evocation of the spiritual realm. As Gary Lachman puts it, "Kandinsky saw in music the non-material art par excellence, and he wanted to achieve in painting what he felt composers had already accomplished: liberation from the material world. In this need to map out the cartography of the inner realms, Kandinsky found a parallel in Theosophy. Although the aura was a spiritual phenomenon, Besant, Leadbeater, and Steiner believed it could be approximated." For Kandinsky, abstraction was the key to this. Interestingly, Kandinsky experienced synaesthesia. It seems that the way in which he experienced colors and forms as linked to sounds and emotions, further strengthened his conviction that visual art could provide a window into unseen, intangible, metaphysical realities.

Einige Kreise (Several Circles) (1926), reflects some of the specifics of Kandinsky's commitment to abstraction and symbolism. For example, he described the circle, which features in several of his works, as "the synthesis of the greatest oppositions. It combines the concentric and the eccentric in a single form and in equilibrium. Of the three primary forms, it points most clearly to the fourth dimension." Also present in Several Circles, as in many of Kandinsky's Theosophy-inspired paintings, is a sense of vibration or pulsation created by overlapping flat forms, as well as the use of offset fields of similar but slightly different hues. Algeo explains that the "theosophical view of all matter - dense and subtle - as vibrations at different frequencies within an ultimate substance provided Kandinsky with an explanation of how art could affect humanity and the world. The vibrations within our psyches and minds respond to the vibrations around us, and in turn influence those outer vibrations. Our feelings and thoughts respond to those of others, and help to shape the atmosphere of feelings and thoughts in which we all live."

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

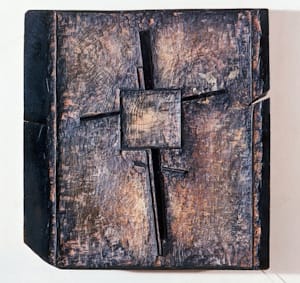

The Pyramidal Image

German artist Joseph Beuys, who was involved with several artistic groups and movements during his career (including Fluxus, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art), was influenced by Christianity and Theosophy in many of his works, including The Pyramidal Image (1979). Curator Ann Temkin notes that Rudolph Steiner was a particular influence on Beuys, particularly "Steiner's understanding of Christ as the living force empowering all human creativity. Steiner's 'spiritual science' replaced faith in an external being with a focus on one's innate potential, a belief that found expression in Beuys's famous declaration 'Everyone is an artist'."

As Jan Verwoert and Donald Kuspit have noted, Beuys also viewed himself as a modern-day "shamanistic healer [...] the last representative of the venerable tradition of avant-garde artists who believed their task to be one of helping humanity to heal the alienation of modern life." Beuys himself once stated "my intention: healthy chaos, healthy amorphousness in a known medium which consciously warmed a cold, torpid form from the past, a convention of society, and which makes possible future forms." In this, he echoes the writings of Theosophists like Blavatsky and Besant, who wrote extensively about processes of mental and spiritual healing.

Temkin writes that "while [Beuys] was willing to speak volumes on his theories of art and society, he displayed great reticence when it came to the matter of his art objects." Thus, we the viewers are left on our own to seek meaning in his works. However, as Temkin states, "the process of separating the important strands that inform his work - alchemy, the Christian tradition, anthroposophy, folklore, literature, and the history of science - reveals the extraordinary breadth of the thinking that underlay the methods of Beuys's art." In The Pyramidal Image, the form of the triangle was likely intended to represent several religious and Theosophical concepts. For instance, for Theosophists, the triangle is generally seen as a symbol of the soul's desire to escape from duality (represented by the base of the triangle) toward "higher unity" (represented by the point at the top of the triangle). Likewise, the triangle in Theosophy often represents a mountain, symbolizing moral and spiritual ascent. Upward-facing triangles are associated with the masculine, while the downward-facing triangle is associated with the feminine. Moreover, as Theosophists embrace the study of all religions and view all world religions as developing out from an original, universal, now-lost religion, they also read into the triangle symbolism pertaining to various trinities and triads, such as Christianity's Holy Trinity (the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit), the ancient Egyptian triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus, and the Hindu "Trimurti" of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.

2 works on printed paper, oil paint - The Tate, London

Origins

Madame Blavatsky

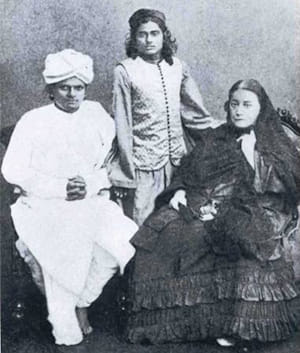

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (more commonly known as Madame Blavatsky) is recognized as the founder of Theosophy, and the tenets of the movement are based largely on her writings. She was born Yelena Petrovna von Hahn in 1831 in Yekaterinoslav (then part of the Russian Empire, now part of Ukraine) and baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church. Her mother, Helena Andreyevna Hahn von Rottenstern, was the daughter of Princess Yelena Pavlovna Dolgorukaya. Helena's father was Pyotr Alexeyevich Hahn von Rottenstern, a descendant of the German Hahn aristocratic family and an officer in the Russian Royal Horse Artillery.

Pyotr's military career meant that the family was constantly moving around. When she was two, Helena and her mother moved to Odessa, where her maternal grandfather Andrei Fadeyev, a civil administrator for the imperial authorities, had recently been posted. Fadeyev was later appointed as a trustee for the nomadic Kalmyk people of Central Asia, so Helena and her mother moved again, this time to Astrakhan, where they befriended the Kalmyk, a Tibetan Buddhist people. This religion would greatly influence Helena's spiritual worldview, just as her nomadic lifestyle would inform her later world travels. Between 1836 and 1840, the family continued to move frequently. During the 1830s three younger siblings were born, one of whom died in infancy. After the family moved back to Odessa, in 1842, Blavatsky's mother died of tuberculosis, aged just 28. Helena and her two younger siblings returned to live with their maternal grandparents, this time in Saratov, where Fadeyev had become Governor. Blavatsky returned with him over several summers to Astrakhan, where she learned horseback riding and some Tibetan.

Accounts of Blavatsky's childhood indicate that she was an avid reader, largely educating herself, and that she was strong-willed, cheeky, and scornful of the aristocratic way of life. Later in life, she embellished elements of her early biography, including that, while in Saratov, she began experiencing "astral projection" (projecting the consciousness out of the body to travel on the "astral plane"). She also claimed to have had childhood visions of a "mysterious Indian man" named Master Morya, whom she met later in life.

At 17, Helena married a Russian military officer three times her age, Nikifor V. Blavatsky. The marriage was never consummated, according to Helena, and they separated after a few months. She, a servant, and a maid were sent to Odessa to reunite with her father but, by her own account, she fled en route to Kerch (modern-day Crimea) and bribed a ship's captain to take her to Constantinople, where she claimed she was summoned by Master Morya. Her extraordinary and possibly apocryphal world travels began at this point. She would later recount spending the next 25 years on the move between the Middle East, Egypt, Greece, Eastern Europe, France, England, Tibet, Asia, Canada, the United States, and India. Little evidence supports this narrative, however. According to her biographer Peter Washington, from her escape in Kerch onwards, "myth and reality begin to merge seamlessly in Blavatsky's biography".

What is more likely is that Blavatsky embarked on a career as a spiritual leader from this point. Her own narrative sees her spending time with Native North American communities and with spiritual leaders (such as rabbis) with whom she studied a range of theological topics. In England, she claimed to have finally met Morya, the "Master", and to have lived in Tibet with Morya's friend, the Master Koot Hoomi. Blavatsky stated that these masters taught her how to cultivate psychic abilities such as clairvoyance, telepathy, mind control, and astral projection.

The Birth of Theosophy and The Theosophical Society

In 1873, after supposedly being instructed by Morya to return to the United States, Blavatsky moved to New York. Shortly thereafter, her father died, leaving her a sizable inheritance. In New York she formed a close friendship with the journalist, lawyer, and freemason Henry Steel Olcott, and the two moved in together and began organizing lectures on esoteric themes. Through these they met the Irish spiritualist William Quan Judge, and in 1875, Blavatsky, Olcott, and Judge founded the Theosophical Society. Although the movement was centered on New York, the society's permanent headquarters were established in India in 1882.

Between 1875 and 1877, Blavatsky wrote her first book, Isis Unveiled, in which she developed many of the core ideas of Theosophy, drawing upon a range of existing religious and esoteric texts. In 1879, Blavatsky and Olcott launched a monthly journal titled The Theosophist, which still in publication today. In 1888 she published her two-volume work The Secret Doctrine, which picked up where Isis Unveiled left off.

Blavatsky continued to travel extensively throughout her life, and to meet with religious, esoteric, and psychic groups and leaders, as well as developing the principles of Theosophy. When she died in 1891, she had become a messianic figure for thousands of people, and branches of the Theosophical Society had been established on nearly every continent.

Defining Theosophy

Blavatsky wrote that "Theosophy, in its abstract meaning, is Divine Wisdom, or the aggregate of the knowledge and wisdom that underlie the Universe - the homogeneity of eternal GOOD; and in its concrete sense it is the sum total of the same as allotted to man by nature, on this earth, and no more". Etymologically, the term Theosophy comes from Ancient Greek, and translates as "God-wisdom".

Theosophists state emphatically that Theosophy is not a religion, and that "there is no religion higher than truth." They insist that Theosophy is instead a system for understanding the "essential truth" underlying all religions, philosophies, and sciences. As such, Theosophists promote comparative study of many different religions, philosophies, and sciences. They often have other religious affiliations, such as Christianity or Hinduism.

However, many scholars classify Theosophy as a religion (or a "hybrid religion", according to the literature scholar J. Jeffrey Franklin), or as a form of occultism and esotericism. Certainly, Theosophy draws heavily from Eastern religions like Hinduism and Buddhism - indeed, the movement played a major role in introducing Eastern religions to the West. It can also be compared to older European philosophies like Gnosticism and Neoplatonism.

Theosophy promotes a monist belief system, indicating one single, divine Absolute from which the universe emanates. It teaches that there was once a singular, ancient, "universal religion" from which all other modern world religions evolved. This long-lost, ancient religion holds the "Divine Wisdom" (also called the "Wisdom Tradition," the "Perennial Philosophy", and the "Secret Doctrine") which, when accessed, can provide answers to all the mysteries of life, nature, and the universe.

Theosophists believe that the human soul is reincarnated, following the laws of karma. The soul follows the goal of spiritual emancipation, which can be approached in life through ethical social relations. However, Theosophy does not offer the specific ethical guidelines or rules for moral conduct that most religions do. The core tenet of Theosophy, as put forth by Blavatsky and the other founders of the Theosophical Society, is "to form the nucleus of a universal brotherhood of humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour".

One of the most controversial beliefs in Theosophy is that there exists a group of highly evolved spiritual adepts around the world (mainly around the Tibetan Himalayas), known as "Masters" (or Mahatma or Adepts). These individuals have access to a realm of knowledge derived from the lost, ancient religion Theosophists at the core of all present-day belief. When this ancient religion is revealed to the modern world, it will be with the help of these Masters. They are deemed to possess superior personal ethics and to have supernatural and psychic powers (such as clairvoyance and astral projection). Masters are said to choose worthy disciples for apprenticeship or "chelaship". This involves a probationary period during which the apprentice must live a life of physical purity, chastity, and humility.

Notable historical figures believed to have been Masters include Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Archangel Michael, Abraham, Moses, and Solomon, Gautama Buddha, Confucius, Pharaoh Amenhotep III, Leonidas (the King of Sparta), the seventeenth-century German philosopher and theologian Jakob Bohme, and several eighteenth-century figures including the Italian occultist and magician Alessandro Cagliostro, a mysterious adventurer known as the Count of St. Germain, and the German physician and astronomer Franz Mesmer.

Theosophy was originally derived almost entirely from the writings of Blavatsky. But it was expanded on and altered by a number of her followers, peers, and even dissenters. This elaboration of Theosophical thought across generations makes it comparable to major religious and political belief systems, separating it from obscure cults based on the personality of one individual.

Neo-Theosophy

After Blavatsky's death, other influential Theosophists, like Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, continued to propagate and revise Blavatsky's teachings. Born in 1847, Besant was a British social reformer, a campaigner for women's rights, a freemason, and a proponent of Indian nationalism. She met Blavatsky in 1890 in Paris, joined the Theosophical Society shortly thereafter, and began lecturing widely on theosophical topics. She became the president of the Theosophical Society after Olcott's death in 1907.

Besant worked closely with fellow British Theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater. Born in 1854, Leadbeater joined the Theosophical Society in 1883 and met Blavatsky one year later, subsequently travelling to India to be trained by Masters. Besant and Leadbeater's writing on Theosophy (which form so-called "Neo-Theosophy") closely mirror Blavatsky's. However, they shifted focus more toward studying mystical experiences, cultivating clairvoyance, and the exploration of past lives.

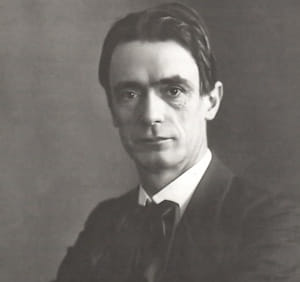

Many other Theosophists published books or presented lectures that opened up new pathways in Theosophical thinking. These include Rudolph Steiner, an Austrian architect and social reformer. As a child, Steiner believed he had spiritual experiences, including interacting with the spirit of a deceased aunt. Like Besant and Leadbeater, he also claimed to be clairvoyant. He was particularly interested in the relationship between science and spirituality, and referred to his earlier philosophical work as "spiritual science."

In 1899, Steiner became very involved in the Theosophical Society, giving lectures and becoming the head of the society's German section in 1902. In 1904, he was appointed leader of the Theosophical Esoteric Society for Germany and Austria.

Steiner's brand of Theosophy differed from others in that it was based more on Western than Eastern traditions, and was concerned with how Theosophical principles played out in European society. Such differences led Steiner to break off from the Theosophical Society in 1912, taking the majority of the German section with him. Steiner then developed his own spiritual movement, Anthroposophy, and formed the Anthroposophical Society.

Theosophy and Art

From the very beginning, Theosophy inspired artists to explore its ideas and themes. The Theosophical Society's early leaders, Blavatsky and Besant, also produced art of their own. Art was important for Steiner too, according to the writer and anthroposophist Michael Howard, who argues that, "far from being dated, Steiner's account of art and its relation to spiritual experience is [...] probably ahead of its time." For Howard, "Steiner demonstrate[d] that our individual creative activity is not solely a personal affair. Our creations do not originate out of nowhere, nor solely out of ourselves, but from an objective world of spirit with which we are intimately related in the depths of our being. He shows that our creations have significance beyond ourselves and beyond the recognition they receive."

Early on, the influence of Theosophy on artists was evident in the Netherlands in particular, with 40 Dutch artists participating in a 1904 exhibition in Amsterdam organized as part of the Theosophical Society's International Convention. As art historians Charles Cramer and Kim Grant note, "theosophy aligned so well with modern art because it validated the idea that European art's traditional naturalistic style, which (they believed) merely imitates the surface appearances of nature, is inadequate to explain the deep underlying mysteries of the universe. For the Theosophists and the artists who were influenced by them, there are truths inaccessible to the scientific method, and a meta-reality beyond the reach of human perception."

Theosophy was also an important source of inspiration for better-known artists. These included pioneers of Abstraction such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. Touching on the theme of abstraction, Cramer and Grant state: "theosophy was a source for many artists who sought higher spiritual truths and a non-perceptual basis for their art, and it validated the idea that a fully spiritual art would leave behind all basis in natural objects and would be fully abstract." They add: "theosophy was also undoubtedly compelling to some artists because of its suggestion that the artists themselves could be counted among the initiates, and that they had a mission to enlighten humankind." However, the styles through which artists expressed Theosophical ideas and concepts varied greatly, and were not solely limited to Abstraction.

According to Cramer and Grant, "the connection between Theosophy and formally-innovative modern art begins in the late-nineteenth century, when some artists and writers reacted strongly against the materialism of an age dominated by science and industrialization." They cite art critic Albert Aurier, who wrote in 1892 that "the nineteenth century, after having proclaimed for eighty years, in its infantile enthusiasm, the omnipotence of observation and of scientific deduction, after having affirmed that no mystery could survive its lenses and its scalpels, seems finally to realize the vanity of its efforts, the puerility of its boasts."

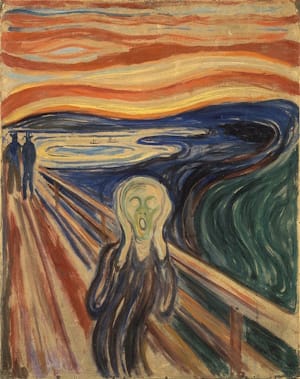

Theosophy emerged in this historical moment, piquing the interest of many modern artists. These included the French Symbolist painters Paul Gauguin and Paul Sérusier, Lithuanian painter and composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, and Norwegian painter Edvard Munch. Art historian and curator Bruce Kamerling notes that "Symbolist art, by using rhythms, colors, and symbols, created visual images that conveyed ideas, emotions and moods far above the obvious level of what was actually being depicted. It was an art that appealed to those who wished to remove themselves from the materialism and boredom of everyday life, and seek a higher level of consciousness." There was a clear connection to Symbolism in the attempt of Theosophists and Theosophy-influenced artists to pierce the veil of everyday reality. In this sense, Symbolism can be seen as closely aligned with Theosophy.

The Symbolists, and in particular the Nabis - a group of painters also connected to Post-Impressionism, and influenced by Paul Gauguin - were amongst the earliest artists inspired by Theosophy. In particular, they admired the writing of the Theosophist Edouard Schuré. According to Cramer and Grant, Schuré's book Les Grands Initiés (1889) "recounts the esoteric wisdom of an eclectic group of spiritual 'initiates,' including Krishna, Hermes, Moses, Pythagoras, Plato, and Jesus".

Paul Sérusier's Portrait of Paul Ranson shows the Nabi artist in an elaborate blue-and gold robe, holding a gold staff decorated with symbols, reading from a medieval-style illuminated manuscript. Behind him a red circle creates a mystic halo, and also shows the flat bright colors and abstract designs favored by the Nabis. As Cramer and Grant state, "the juxtaposition of Ranson's 19th century pince-nez, waxed mustache, and well-trimmed goatee with this Medieval and esoteric regalia is somewhat incongruous (and may well have been intended to be tongue-in-cheek), [but] it does demonstrate the spiritual aspirations of the group".

Concepts and Styles

Symbolism and Allegory

Theosophy teaches that alternative realities and dimensions lie behind the "veil" of the world we see and experience. As these hidden realities can be difficult to describe, symbolism and allegory are often employed in the language and visual art of Theosophy. Artists inspired by Theosophical doctrines use a variety of established symbols from various world cultures and religions. These include the triangle to represent the holy trinity as in Christianity, the peacock's tail to represent divinity as per Hindu tradition, and the ouroboros (a serpent eating its tail) from ancient Egypt and Greece, a symbol of eternity.

While the above, generic symbols might be used by followers of Theosophy in expressing their theories visually, better-known artists tended to develop more individual symbolic systems, interpreting shape and color based on Theosophical ideas. The De Stijl artist Piet Mondrian, for example, would compose his paintings using only yellow, blue and red, and include only horizontal and vertical lines. While this might seem an arbitrary and extreme sort of abstraction, it can actually be connected with ideas from the Theosophist mathematician M. H. J. Schoenmakers's 1915 book Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld (The New Worldview). Schoenmaker was interested in "the inner structure of reality" and how this could be conveyed by the simplest possible colors and forms.

Likewise, the artist Wassily Kandinsky developed a complex theory of color symbolism in his 1912 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, influenced by the Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater's theories on color symbolism. Kandinsky wrote of blue as being "the typical heavenly colour," elaborating that "when very dark, blue develops an element of repose" and "when it sinks into black, it echoes a grief that is hardly human."

Abstraction

As Cramer and Grant write, "Theosophy was a source for many artists who sought higher spiritual truths and a non-perceptual basis for their art, and it validated the idea that a fully spiritual art would leave behind all basis in natural objects and would be fully abstract." Artists inspired by Theosophical doctrines, including Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Georgia O'Keeffe, saw abstraction, not figuration, as the best means for depicting the "hidden realities" that lie beyond the "veil" of our regular existence. Abstraction was also the best means of conveying the spiritual, occult, and supernatural ideas central to Theosophical thought. One of the artists most influenced by Theosophy, Hilma af Klint, considered abstract art to be the "spiritual precursor of a utopian social harmony, a world of tomorrow".

A range of different styles of abstraction were used by artists engaged with Theosophy. Mondrian and his followers saw minimalist, geometric abstraction as the true path to connection with the spiritual realm (as per the writings of more mathematically-minded Theosophists, like M. H. J. Schoenmakers). Others, like O'Keeffe, were preoccupied by the idea, common in Theosophy, that nature contained hidden spiritual dimensions, expressing these through more organic forms of abstraction. All of them, however, as art historian Magda Michalska writes, saw abstraction as spirituality's "real manifestation because abstract art stepped beyond what's simple and superficial."

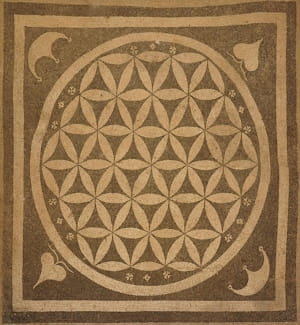

Shapes, Forms, and Sacred Geometry

While symbolism is central to Theosophy, any given shape or form can suggest a multitude of meanings according to the tenets of Theosophy. This reflects the variety of the sources on which the belief system draws, including many ancient and modern cultures and religions. The square, for example, could be understood as representing the feminine and female reproduction as per Greco-Roman tradition, or as representing stability, marriage, heaven, and/or culture as per Hindu tradition, or as representing the end of times as per Christianity.

To take one example of how a particular shape could be interpreted in a range of ways under the banner of Theosophy, the Russian Suprematist and Constructivist painter Kazimir Malevich, who was influenced by Theosophy, understood the cube as symbolizing the "fourth dimension" of life, the dimension that would survive after the death of the body. Squares and cubes featured prominently in Malevich's work with this association.

Accepting these distinctions, all Theosophical beliefs hold that certain, core mathematical and geometrical principles can be intuited in the appearances of the natural world, and serve as links to the spiritual realm. The North-American Theosophist and architect Claude Bragdon once stated that "mathematics is the handwriting on the human consciousness of the very Spirit of Life". The British artist, architect, and scholar of sacred geometry Keith Critchlow writes that "the face of a flower can remind us of the geometry that underlies all existence, ... a powerful way to reconnect us with the idea that we are all one."

"Sacred Geometry" is present in much art inspired by Theosophy. Sacred Geometry refers to the understanding that particular shapes and harmonious combinations of forms have spiritual significance. It ranges from simple forms such as grids to more complex patterns such as mandalas and flowers of life. Architect Steve Hendricks writes that "sacredness has implicit in it the recognition that there is an underlying order to creation and that we are a part of it. Man is created in the image and likeness of God. Our ideal human form is therefore a reflection of our Creator. When we attempt to mirror the beauty inherent in all of creation, our work can be animated by something outside of ourselves. Geometry can help in this discovery." Hendricks also notes that "geometry is a word meaning, literally, to measure the earth, from geo for earth and metric for measure. The ancient Egyptians practiced and preserved it as a highly developed knowledge inherited from people who were prehistoric to them."

Color

One of the most common forms of symbolism in art influenced by Theosophy is color symbolism. Theosophists like Blavatsky, Besant, and Leadbeater wrote extensively about the inherent meanings of colors and the specific emotions evoked by specific colors. So too did artists such as Kandinsky and František Kupka. Kandinsky wrote that "each color lives by its mysterious life"; "color is a power which directly influences the soul"; "color provokes a psychic vibration. Color hides a power still unknown but real, which acts on every part of the human body."

Such individual assertions on the meanings of particular colors tended not to align with each other. Theosophy does not therefore offer universally applicable or objective systems of color value. Just as Theosophy can interpret shape-symbols in myriad ways due to the wide-ranging sources upon which it draws, the same is true of color symbolism. Yellow, for example, has been taken to represent everything from excitement to sickness to truth to immortality across different cultures and time-periods.

Synesthesia

A core belief in Theosophy is that all things, beings, and energies in the universe are interconnected. It comes as no surprise, then, that Theosophy takes a particular interest in synesthesia. This refers to the stimulation of multiple senses at once, such as seeing colors when listening to music. Historian Benjamin Breen refers to Besant and Leadbeater's 1901 book Thought-Forms, an important Theosophical text which explores "underlying associations between words, colors and sounds" as essentially a "book about synesthesia". Besant and Leadbeater also devised theories of color, seeing particular colors as corresponding to particular feelings and emotions.

Besant and Leadbeater's book strongly influenced Kandinsky's theories concerning the relationship between colors, forms, and emotions, as expressed in his 1912 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. It also influenced František Kupka's 1923 text Creation in the Plastic Arts. Italian futurist painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni also cited the book as an influence, and it is believed that Thought-Forms was a source of inspiration for Edvard Munch, who claimed to see colored "auras" that encircled people's heads "like a halo".

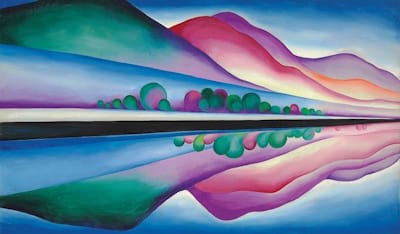

It is not surprising that synesthete artists such as Kandinsky, O'Keeffe, and Čiurlionis became interested in Theosophy. O'Keeffe, for example, experienced chromesthesia (seeing sounds as colors), and became deeply invested in the relationships between music, color, form, and emotion suggested by Theosophy. She and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, explored these ideas in relation to the transcendental qualities of nature, as in paintings such as Lake George Reflection (1921-22).

The literary critic Timothy Ray Fox has noted that synesthesia and Theosophical ideas are also evident in the work of various writers and artists. These include the Nicaraguan poet Ruben Dario and Argentine poet Leopoldo Lugones. Fox writes that, in the works of these poets, "Synesthesia and related literary techniques are employed on a textual level to create a holistic sensorial effect. This stimulation of the various senses in the reader is intended to bring to the literature a sense of the spiritual and musical nature of words and images. On the level of subtext, synesthesia, alliteration, rhythm, and a sort of polyphony of voices serve as ambiguous signs which suggest spiritual experiences and realities."

Energies, Spirits, and Hidden Dimensions

Many artists inspired by Theosophy sought to represent hidden energies, spiritual beings, hidden dimensions, and related phenomena in their art. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats, for example, was heavily involved with the Irish Theosophical Society, exploring themes of hermeticism, spiritualism, and other arcane religions and symbolism in his work. During the 1880s he painted a mural for the then-meeting place of the Society in Dublin, along with the critic and writer George William Russell. The design included semi-abstract human forms emerging from mysterious clouds and tunnels of light, a good example of the representation of otherworldly spirits in Theosophical art.

Later Developments

Theosophy has influenced dozens, if not hundreds, of other esoteric movements and philosophies. These include Anthroposophy, the Church Universal and Triumphant, and the New Age. The historian of religion Wouter Hanegraaff states that Theosophy helped to establish the "essential foundations for much of twentieth-century esotericism." The influence of Theosophy on art and artists of the past century and more is thus impossible to sum up neatly, not simply because the movement itself is far-reaching and varied, but because it has influenced many subsequent, equally complex, philosophical and religious movements.

Some contemporary artists, like British artist Zarah Hussain, feature sacred geometry in their art. However, it is not clear whether Hussain and other artists draw inspiration from Theosophy or rather from other historical sources such as Islamic art, which has long integrated Sacred Geometry into its designs. Certainly, Theosophy played a significant role in popularizing several principles and ideas in the Western world. These include the idea of reincarnation, the interconnectedness of all things in the universe, and the moral imperative for all people to seek fraternity and love. These core tenets are expressed in countless ways by countless artists up to this day.

A more recent genre of art that appears as a more direct offshoot of Theosophy is Visionary (or Sacred) Art, which can be understood as beginning around the 1960s. American visionary artist Alex Grey explains that the visionary artist's mission "is to make the soul perceptible," and that "visionary art encourages the development of our inner sight." He adds that "the visionary realm embraces the entire spectrum of imaginal spaces; from heaven to hell, from the infinitude of forms to formless voids. The psychologist James Hillman calls it the imaginal realm. Poet William Blake called it the divine imagination. The aborigines call it the dreamtime; and Sufis call it alam al-mithal. To Plato, this was the realm of the ideal archetypes. The Tibetans call it the sambhogakaya; the dimension of inner richness. Theosophists refer to the astral, mental, and nirvanic planes of consciousness. Carl Jung knew this realm as the collective symbolic unconscious. Whatever we choose to call it, the visionary realm is the space we visit during dreams and altered or heightened states of consciousness."

Visionary Art owes much to the earlier Vienna School of Fantastic Realism (active from the 1940s to around the 1960s or 70s), whose artists (including Ernst Fuchs, Helmut Leherb, Arik Brauer, and Wolfgang Hutter) were influenced by esoteric movements such as Theosophy and its offshoots. Fuchs was, in fact, a teacher to many important visionary artists, like Mati Klarwein, Robert Venosa, and De Es (Schwartzberg). Closely related to Visionary Art is Psychedelic Art, which began around the late 1960s, as artists attempted to visually recreate the experience of taking psychedelic substances such as DMT, psilocybin, and LSD.

Theosophical principles have also influenced architectural projects. American architect, artist, and writer Claude Fayette Bragdon was active in the American Theosophical Society. In his books The Beautiful Necessity (1910), Architecture and Democracy (1918), and The Frozen Fountain (1932), he put forth a distinctly Theosophical approach to architectural design which influenced several younger architects, most notably Buckminster Fuller.

Theosophical Society archivist Janet Kerschner explains that "Bragdon conceived of architecture as rhythm in space and attempted to bridge societal divisions through a universal language of geometric design. [...] With a true Progressive Era sensibility, Bragdon was concerned with how individualism fits within a social order, and how to apply his art to promote brotherhood. His buildings emphasized open planning, glass, color, rooftop living, and ornamentation based on Pythagorean principles of harmony."

More recently, in 2016, the Mexican architect and artist Santiago Borja created the site-specific installation A Mental Image - Blavatsky Observatory on the roof of the Sonneveld House museum in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands. The work took the form of an observatory capped by a wooden structure with an open oculus at the center, and an astrological chart on the observatory floor. The space, dedicated to Blavatsky, was intended by Borja as a place for meditation and quiet contemplation.

According to Borja, "Blavatsky was a strong advocate of a modern universalist brotherhood and the Theosophical Society was an inclusive group, where everybody was accepted regardless of gender, political and religious affiliation. [...] Maybe this is too good to be true, but if it was really true, for me this is quite a revolutionary thing, and it planted the seed, not only for social utopias but also for modern universalist app¬ roaches in art and design [...]. I have the feeling that this kind of idea allowed certain architects such as those involved in the Bauhaus or even Le Corbusier, to try to find a way for architecture that could solve, for example, the housing problem all over the planet without considering climate or socio¬political or even economic differences."

Useful Resources on Theosophy and Art

- Isis UnveiledOur PickBy Helena Blavatsky

- The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and PhilosophyOur PickBy Helena Blavatsky

- The Key to TheosophyBy Helena Blavatsky

- The Ancient WisdomOur PickBy Annie Besant

- Theosophy and the Theosophical SocietyBy Annie Besant

- A Textbook of TheosophyOur PickBy C.W. Leadbeater

- Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and WorkBy Gary Lachman

- Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the CosmosOur PickBy Rudolf Steiner

- Theosophy: History of a Pseudo-Religion (Collected Works of Rene Guenon)By Rene Guenon and James Richard Wetmore

- Theosophy Explained: Questions and AnswersBy Pestanji Temulji Pavri

- Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the AgesBy Robert Ellwood

- The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 - 1985Our PickBy Maurice Tuchman

- On the Spiritual in ArtOur PickBy Wassily Kandinsky

- Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts and the American WestBy Christopher Scheer and James Mansell

- Theosophy And ArtBy C. Jinarajadasa

- ColourBy Rudolf Steiner

- Art as Spiritual Activity: Rudolf Steiner's Contribution to the Visual ArtsOur PickBy Michael Howard

- Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the FutureBy Tracey Bashkoff

- Hilma af Klint: VisionaryOur PickBy Kurt Almqvist, Louise Belfrage, and Margaret Ax:son

- Hilma af Klint: Occult Painter and Abstract PioneerOur PickBy Åke Fant

- Hilma af Klint: The Art of Seeing the InvisibleBy Kurt Almqvist and Louise Belfrage

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI