Summary of Félix Vallotton

Vallotton never quite reached the heights of fame of some of his avant-garde contemporaries, but he developed his own unique style and history now views him as one of the most original artists of his era. His status stands on a body of work that encompasses portraits, satirical prints, interior narratives, landscapes and still lifes. His early printmaking caught the eye of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard who invited him to join the Nabis group. Though he never really settled as a member of Nabis, his affiliation with the group brought him into contact with a circle of literary bohemians. Through these new associations he was able to plot a more singular path that saw him make his name via a collection of groundbreaking satirical woodcuts for avant-garde left-wing journals. As his career evolved, Vallotton turned his dispassionate eye more and more towards painting. Transferring the block technique of his printmaking to his painting, his distinctive vision offered a fine balance between Realist and Symbolist techniques that saw many of his mature works convey a palpable sense of psychological disquiet.

Accomplishments

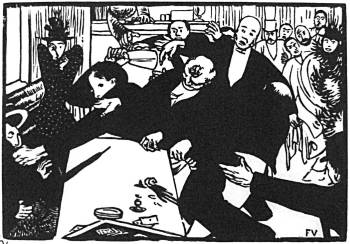

- In creating some of the most visually distinctive, and bitingly satirical, images of turn-of-the-century Parisian life, Vallotton earned the title of greatest printmaker of his generation. Credited in fact with reviving the art of woodcut printing, he drew on the traditions of Ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints, by eighteenth century artists such as Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige, to create biting political narratives whose effect was heightened through his bold contrast of jet black ink on white paper.

- Though he was at the center of the most experimental period of Western art, Vallotton remained mostly dedicated to realist representations. Resisting the abstract preferences of the avant-garde, he produced a more idiosyncratic style of painting that the public and critics of the day failed to fully comprehend and, as such, he can be credited with widening the parameters of what it meant to be a "modernist". Indeed, his daring and originality led to a habit for creating controversy that the avant-gardist would have been proud of.

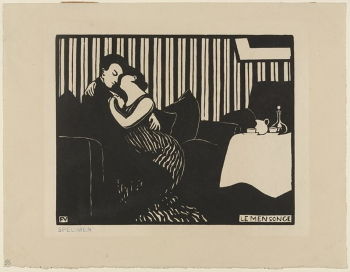

- Vallotton was famous for an album of 10 prints entitled intimacies, a collection of domestic vignettes chronicling intimate liaisons between bourgeois couples. In Vallotton's unravelling of the forbidden mores of private bourgeois life, he had, according to historians such as Merel van Tilburg, brought art into line with late-nineteenth century literature in the way commentaries on the hidden drives of the human psyche were anticipating the imminent birth of psychoanalysis.

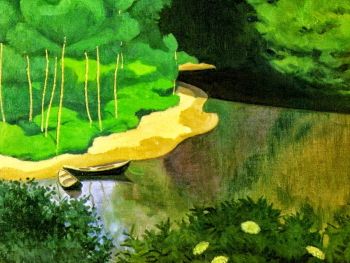

- Based on sketches and photographs, but formed in his imagination, Vallotton's paysages composés ("patched together" landscapes) were unique and possessed an otherworldly quality that might have pre-empted the Surrealists. Through their bold outlines, flattened colors and silhouettes, images such as The Sheaves (1915) and The church of Souain in silhouette (1917) remain some of the most moving symbolic meditations on the affects of the Great War.

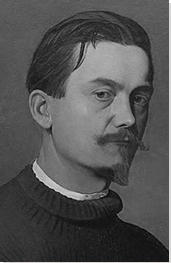

The Life of Félix Vallotton

"The master of eerie estrangement", the Royal Academy labelled him. It was a title Vallotton might have appreciated given his preference for painting "people who are level-headed but who have an unspoken vice deep inside them" ... a state of being, he readily admitted, "that I share".

Important Art by Félix Vallotton

Mr Ursenbach

In 1883, a 17-year-old Vallotton wrote a letter to his brother Paul bemoaning his new life in Paris: "The professor is pleased with me, but I am not pleased with myself and sometimes feel sad [...] My heart sinks when I think of what I am about to study and realise that I am nothing compared with the great artists who startled the world at the age of fifteen". It was not a view shared by Jules Lefebvre (his professor) who wrote to Vallotton's worried father stating: 'Monsieur, I hold your son in high esteem, and have only had occasion to compliment him up to now. I think that, if I had such a son, I would not be worried about his future at all and would unhesitatingly be prepared, with the bounds of possibility, to make sacrifices over and over again, in order to help him". Lefebvre concluded: "I am so interested now in those who are prepared to work - your son is one of those. [He] will bring you fame".

Firmly grounded in the academic tradition in which he was trained, Vallotton's first success demonstrates his not inconsiderable technical skill. In 1885 he submitted the Portrait of Mr Ursenbach to the Salon jury. The jury, on which Lefebvre sat, accepted the painting for public exhibition. The setting for the portrait is the sitter's (an American mathematician and neighbour of the artist) dour study while Ursenbach is seated in his armchair in a rigid upright pose. He is not a man at ease with himself (or, so it seems, with the teenage artist) and his face carries a stern expression. His hands rest upon his knees while his gaze is directed outside of the frame. Though it is executed with aplomb, it remains an unusual portrait and it was probably Ursenbach's unconventional pose that grabbed the attention of the jury and visitors to the exhibition. The portrait divided critics but it gave a once downhearted young artist all the incentive he needed to embark in earnest on his life-long career. In 1889 Vallotton exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris as the Swiss representative and won favorable notices for the same portrait.

Oil on canvas - Kunsthaus Zurich

The Money: Intimacies (Intimités)

Vallotton is attributed with reinventing woodcuts by introducing them to a new audience through contemporary, psychologically charged, subject matter. With his Intimacies series of 10 prints, he had moved away from his overt political statements to observe private interior settings featuring the "intimacies" of Parisian bourgeois couples. The works, which remain, arguably, his best known, feature smooth black blocks of wood, cut through with sharp white lines. In The Money, two-thirds of the woodcut remains in black while the cut itself occupies only one-third of the left side of the image. Vallotton shows us a gentleman trying to engage in conversation with his companion. She, however, seems disengaged and her gaze is fixed on something beyond the balcony widow and outside the picture frame. Vallotton creates a sense of ambiguity and dramatic mystery through the image; its title allowing the viewer's imagination to run free with possible (negative) interpretations.

Vallotton was creating these works at a tumultuous time for a city rushing headlong into modernity. The assault on tradition gave rise to feelings of disillusionment and unease, especially amongst the conservative bourgeois class. And at a time when so much focus was on the changing face of the city, it was farsighted of Vallotton to turn his attention to interior worlds. As arts journalist Kitty Jackson observed, "For Vallotton [...] the interior scene seems to subvert our expectation of control, of being 'at home' in your own residence. Instead of posing, looking out from the canvas and sitting steadily for a portrait work, the upper-class people in Vallotton's images are caught off-guard, unposed and unprepared. They are captured mid-conversation, mid-elicit tryst or mid-deception. Their interior world is one of lies, of tension and of disconnection. Vallotton seems to use the interior space as a scene in which to get under the skin of the lavish display of wealth and gentility in Parisian society. He suggests that behind the carefully orchestrated displays of bourgeoisie life there is dislocated, troubling and fractured reality".

La Malade (The Sick Girl)

La Malade has at once the vivid clarity and formal composition of a Dutch Old Master painting and the feel of a chamber play. A maid brings a drink for her sick colleague - posed for by Vallotton's mistress Hélene Chatenay - who has her back to the viewer. On the wall hangs a print of a Madonna and Child by Gustave Doré. The painting is clearly rooted in the traditions of Realism, but there remains something strangely disconcerting about the painting. The maid appears to be posing for the artist rather than attending to her patient, and the curve of the rug and encroaching screen on the left adds to its uncanny, claustrophobic, air. La Malade was perhaps the final culmination of Vallotton's early realistic style before he began to introduce into his painting the simplified style he was already experimenting with in his woodcuts.

Oil on canvas - Kunsthaus Zürich

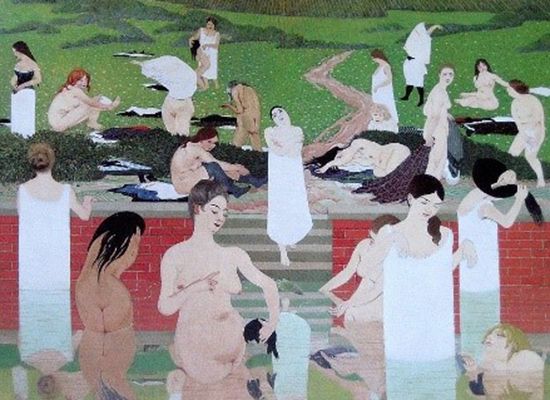

Le Bain au soir d'été (Bathers on a summer evening)

Painted in the same year as La Malade, Bathers on a summer evening illustrates Vallotton's shift from realism to something altogether more symbolic and decorative. In a strangely flattened composition, contemporary women (recognizable as such through their hairstyles and facial expressions) in various stages of undress bathe in, or disrobe beside, a pool. Vallotton flaunts the rules of perspective here: the ploughed lines of the distant fields follow convention by moving towards a vanishing point, while figures of differing sizes appear as if they have been arranged and collaged onto the background; disconnected, seemingly, from their surroundings and from each other. The treatment of some of the women is reminiscent of Manet's Dejeuner sur l'Herbe, and, in the erotic and decorative line drawings, the paintings of Klimt and Schiele. The style in which each of the women is rendered differs too. Some are naturalistically shaped and shaded; others almost encased in white rectangular robes, like pillars rising out of the water. Art historians Dita Amory and Ann Dumas said of this piece that "Its cold eroticism laid the foundations for Vallotton's entire later exploration of the Female nude".

Of all the works Vallotton created during his association with Les Nabis, Bathers on a summer evening was probably the most controversial, even causing a minor scandal when it was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1893. Seen in the context of his earlier satirical works, the painting can be read as an ironic take on fin-de-siècle society and as a caricature of bourgeois leisure pursuits. Vallotton's variation on the theme of "the fountain of life" also provoked bemusement among the critics and public who failed to respond to its originality or to recognize the subtle references to the likes of Rousseau and Japanese ukiyo-e prints. On viewing the work, Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the few to appreciate it, but even he predicted that the police were likely to "come and take it away".

Oil on canvas - Kunsthaus, Zürich

Clair de lune (Moonlight)

Vallotton's association with Les Nabis led to the creation of this painting; a radiant, shimmering and semi-abstract, evocation of moonlight. A river snakes across a darkened landscape, reflecting the radiant full moon and the golden glow it casts on billowing clouds. In its simplified graphic style and rich golden patterns, Vallotton appears to be referencing the decoration of japoniste screens, his own woodcut prints, and Les Nabis theme of evoking inner feelings brought about by a world beyond perceptible reality.

Vallotton would create his reduced, idealized, landscapes in the studio from plein air sketches and snapshots from his Kodak camera. He wrote, "I dream of a painting entirely disengaged from any literal concern about nature. I want to construct landscapes entirely based on the emotions that they have created in me, a few evocative lines, one or two details, chosen, without a superstition of the exactitude of the hour or the lighting". Vallotton had discovered by now that the best way to achieve such results was through the careful planar style reserved previously for his woodcuts.

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

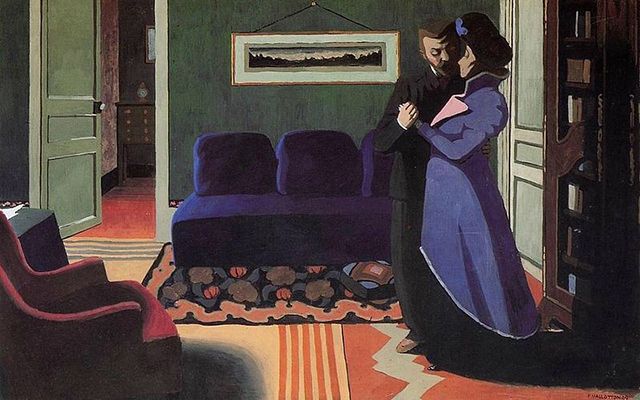

La Visite (The Visit)

In this sumptuous domestic scene, Vallotton lets the viewer in on a private moment, possibly a clandestine tryst between a man and a woman in a Paris drawing room. The strong verticals and horizontals of the room give the image the feeling of a theatrical set. The plush upholstered velvet furniture is echoed in the contours of the woman's coat, while a sinuous shadow extends from the black of the man's suit up the wall. A door is open to another room, probably an adjoining bed chamber, suggesting the couple's illicit intentions.

This is one of numerous images Vallotton painted of intimate moments between men and women, sometimes in restaurants, sometimes at the theater, and often suggesting seduction or coercion, but rarely romance or love. One critic, Octave Mirbeau, has described how, "the figures don't just smile and cry, they speak [...] they express strongly, with the most moving eloquence, when it is Monsieur Vallotton who hears them speak, their humanity and the character of their humanity". Vallotton himself spoke of something mysterious laying beneath the surface of his painting: "I think I paint for people who are level-headed but who have an unspoken vice deep inside them," he remarked. "I actually like this state which I share".

Distemper on cardboard - Kunsthaus, Zürich

Le Ballon (The Ball)

The Ball is one of Vallotton's best known works and was produced when he was still close to Les Nabis. Indeed, the bird's-eye view of figures in parks, gardens or other public places was a trait in paintings by Bonnard and Vuillard. For his take on this theme, Vallotton offers a high viewpoint of a child, his or her face obscured by a broad brimmed yellow hat, adorned with a red ribbon, and from under which a mop of blonde hair has escaped. The child's boots are a dull orange colour while the floating white smock trails behind the child in the wind, emphasising the running pace at which he or she chases the red ball. Set against the tawny expanse of ground, and the deep shadow cast by the trees (under which lies what appears to be a second, light brown, ball), the child brings a vivid splash of light, almost as if being chased by the dark shadow. Across the lake, our eye is drawn to two pale figures standing side by side, one dressed in blue, the other in white. The diminutive size of the two women suggests that they are stood in the far background yet the picture plane is flat and frontal, broken up by the diagonal curve of the lake.

Christine Dixon of the National Gallery of Australia, observed that there is a strong graphic quality to the painting which pays its debt to Vallotton's "dynamic black-and-white wood engravings" that offered "no half-tones, just positives and negatives". Dixon wrote, "Like most of the Nabis, Vallotton admired Japanese woodblock prints, and adapted many themes and stylistic conventions from them. But unlike Vuillard's and Bonnard's images of public-gardens "Vallotton did not decorate each view with ornamental patterns. He reduced rather than augmented the visual elements, and smoothed paint into a material parallel to reality". She adds that Vallotton's was an "outsider's view, and never one of unalloyed delight" and, as such, his child "plays alone, supervised by the adults glimpsed in the background". It is, Dixon concludes, "a city pleasure for the offspring of the bourgeoisie, this solitary ballgame, and any pastime less rowdy or companionable can hardly be imagined".

Oil on cardboard mounted on wood - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

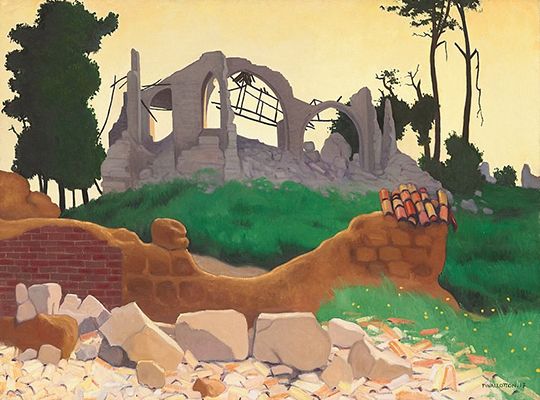

L'église de Souain en silhouette (The church of Souain in silhouette)

Vallotton was 48 when war broke out and he felt redundant on learning that he was too old to serve his adopted country (he become a French citizen in 1900). He was profoundly affected by the violence in reports coming back from the front lines and following the 1916 French victory at Verdun, Vallotton wrote, "Out of the all the horror rises a perfect nobility; we are becoming truly proud to be on the side of humanity, and whatever happens, the French name is made young again with a lustre unknown until now".

In 1917 Vallotton was able to show his patriotism by accepting a commission from the French Ministry of Fine Arts to tour the Champagne front. There he found once proud towns and villages reduced to rubble and ruins. The artist asked himself, "What to represent of all this?". Souain had been the setting for two battles and was now an area used to test the ability of French tanks to cross razed terrains. Silhouetted against the backdrop of a desolate late afternoon sky, the hollow ruins of the church represent the senselessness and destructiveness of the ongoing war. The painting was produced in the studio based on sketches the artist made on his tour. Vallotton endows this view of the church with a cool detachment. His treatment of the subject is in fact more akin to the background painting for an animated film than the kind of meditation one might expect on the wreckage caused by conflict. The flattened colours, bold outlines, silhouetted trees and cartoon-like rendering of the wall, tiles and stone are stylised in the simple manner reminiscent of his woodcut prints.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

La Roumaine en robe rouge (Romanian woman in a red dress)

Returning to portraiture towards the end of his life, Valloton's sitters ranged from renowned cultural figures of the day (such as Edouard Vuillard and Gertrude Stein) to the Parisian prostitute pictured here, Mado Leviseano. His portrait of Leviseano is considered his last important work and is almost photo-realistic in its cold brutality and honesty. Not for the first time, however, Vallotton caused a minor scandal with his painting.

Leviseano slumps, looking withered and despondent, yet trying to retain her allure through a strained smile and a slipping dress strap. The solid red background merely reinforces the blank hollowness of her profession. The artist said of his portraits, "Human bodies, like faces, have their own individual expressions, which reveal, by their angles, their folds, their wrinkles, the joy, the pain, the boredom, the worries, the appetites, and the physical decay imposed by work, and the corrosive bitterness of voluptuousness". Vallotton's late portraits, nudes and landscapes, according to Christopher Le Brun, then President of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, are "magnetic in their controlled intensity and [are] often imbued with a potent atmosphere of uneasiness".

Le Brun's was not a view shared by the public of the day, however. When the painting was donated by Vallotton's family after his death to the Luxembourg Museum in Paris - then the premiere modern art museum in Paris - there was a chorus of complaints from patrons. They took exception to Leviseano's demeanour and broken expression and after three years the museum removed it from display. After pressure from the artist's widow, the painting was finally taken back by the Paris museums and it currently sits proudly on display at Centre Pompidou.

Oil on canvas - Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Biography of Félix Vallotton

Childhood and Education

Félix Edouard Vallotton, and his older brother Paul, were born into a modest Protestant family living in Lausanne, on the shores of Lake Geneva. Felix's father, Alexis, owned a chandlery and grocery shop and would later take charge of a chocolate factory. His mother, Mathilde, descended from a line of furniture makers. The young Félix was a delicate and sensitive boy and, because of the smallpox epidemics that were sweeping Europe, he spent extended periods cosseted in the family home. In addition to his scholastic subjects, which included classes in Greek and Latin, he enjoyed drawing and painting (a passion no doubt fostered in his periods of extended lockdown) and pursued after-school art classes with the painter Jean-Samson Guignard. It was in these sessions that he first demonstrated his precocious talent for depicting subjects with an uncanny precision.

Having graduated from Collège Cantonal in 1882, a sixteen year old Vallotton persuaded his father to take him to Paris so that he could learn more about pursuing a career as a painter. He had passed the entrance exam to the École des Beaux Arts but opted instead for the more relaxed Académie Julian because it focused on "real art" and "naturalism" and offered courses on lithography and other forms of printmaking. Vallotton studied under three great French figurative painters: Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Guillaume Bougereau and Gustave Boulanger. As a student he earned a reputation for hard work but was worryingly reclusive and lacking in self-belief. Nevertheless, his tutors looked upon him as a model student and had great hopes for him.

Vallotton spent much of his free time in the Louvre and he became enamoured with the works of the Renaissance Masters, as well as Goya, Manet, and Ingres. While at the Académie, Vallotton also struck up friendships with the Polish engraver Félix Jasinski and the painter and engraver Charles Maurin. Vallotton painted Jasinski's portrait while Jasinski returned the compliment by teaching Vallotton about the art of engraving. The two men would work together on many future projects.

For his part, Maurin, who was eight years Vallotton's senior, supported his disillusioned friend through letters: "Whatever you lack it is certainly not artistic flair. It is rather some quality of character (please allow me to mention this to you). (I would like you to be as open with me.) From your last letter it emerges that you lack strong will and you are creating difficulties for yourself. But that is not the case. You do have willpower but it does not manifest itself". Even if Maurin's kind words had soothed Vallotton, his woes were merely compounded by financial hardship and he had to call on his father for money to help pay for lodgings, food, and to pay for the hire of models. A homesick Felix wrote to his parents complaining: "I practically never go out. I work from seven in the morning until five in the afternoon. This has not produced any great results so far, everything must work out soon". Happily things did "work out soon" when, in 1885, Vallotton's portrait of one of his neighbours, Mr Ursenbach (a mathematician and Mormon) was accepted by the Paris Salon jury (of which Lefebvre was a member) for exhibition. With that upturn, it seems Vallotton became more systematic, and thus began his lifelong mission of cataloguing of all of his own works (they numbered 1,700 by the end of his life).

Early Period

In 1887, Vallotton distanced himself from the Académie Julian after his Realist portraits received criticism from his erstwhile supporter, Lefebvre. In spite of his conservative Swiss upbringing, and a constraining lack of funds, he immersed himself in Parisian life. Maurin had introduced his friend to the bohemian haunts of Montmartre where he met Henri Toulouse-Lautrec at the cabaret Le Chat Noir. Vallotton moved to the artists' district of Montparnasse where he drew closer to Toulouse-Lautrec and the culture of bohemian Paris. To help make ends meet, he began selling prints of drawings he had made of Rembrandt and Millet, took on part-time work as a restorer in an art gallery and, in 1890, he began contributing art reviews to the Swiss Gazette de Lausanne (an appointment he maintained until 1897).

His Parisian adventure was stalled after he suffered a bout of typhoid fever, followed by a period of deep depression, which saw him return to Switzerland for recuperation. In 1892 Vallotton met French seamstress Hélène Chatenay with whom he shared a relationship until 1899. He also earned money from portrait commissions. Many of his Paris commissions were secured through fellow Swiss ex-patriots living in the French capital. One such friend was the Swiss artist Ernest Bieler who persuaded his close acquaintance, Auguste de Molins, to write a letter of introduction on behalf of Vallotton to Renoir and Degas.

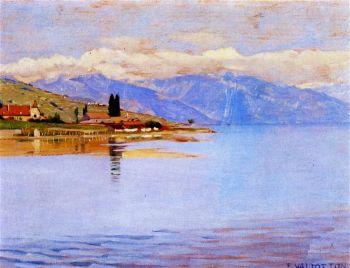

Vallotton's own catalogue of works started to list his engravings from 1887 and in a letter to his parents in late 1889 he told them he had begun working on commissions for a publisher. He earned a good living from his engraving work and by 1891 his wood engravings overtook the number of paintings listed in his personal catalogue. In addition to his engravings and portraits, Vallotton's early period also featured a number of impressionistic landscapes, usually featuring mountain views around Lausanne and Lake Geneva. The artist was fond of his commissioned landscapes and often kept them for his personal collection. One such study was Le port de Pully (Port of Pully) on the lake front located on the shores of Lake Geneva. By this time, however, Vallotton was turning his artistic attentions towards social satire and interior narratives.

Mature Period

In 1892, the critic Octave Uzanne said of Vallotton, "This newcomer who is not a beginner, engraved on blocks of soft pearwood various scenes of contemporary life with the candour of a sixteenth-century woodcut". Indeed, through his growing mastery of woodcut printing, and his keen sense of graphic style, Vallotton became highly sought after by a new wave of French journals, eager to recruit an artist who shared their liberal, sometimes anarchistic, sympathies. Magazines such as Le Courrier Français, Le Rire, Le Cri de Paris and L'Escarmouche paid their star illustrator well for his acerbic and witty illustrations.

Vallotton also exhibited with the inimitable Salon de la Rose+Croix, a gallery run by an association of Rosicrucian devotees that balked at both Classical Art and the Impressionists in favor of promoting their own Spiritualist and Symbolist preferences. Here he exhibited his woodprint portrait of the poet Paul Verlaine (who attended), just one of several literary portraits he made of the likes of Poe, Dostoevsky, Stendhal, and contemporaries including Mallarmé and Rimbaud. According to Oxford academic Patrick McGuiness, Vallotton had "developed a visual shorthand for the literary portrait, creating a style that was totally distinct: a mixture of refinement of effect and economy of means that captured a writer's aura through the deft manipulation of black and white". Ever the outsider, Vallotton was an uneasy fit for the group, however, and only exhibited with them once.

While his politically subversive woodcuts were exposing such themes as police brutality and street demonstrations, his impressively original, but critically vilified, Bathing on a Summer Evening (1892), indicated that he was pursuing a visual language that was less naturalist and altogether more Symbolist - and more erotic - than his early works. Vallotton also found time to design a theater playbook cover for Swedish dramatist August Srtindberg's The Father (1894) and provided illustrations for several books throughout the 1890s including Jules Renard's The Mistress (1896) and Remy de Gourmont's The Book of Masks (1896).

Japanese prints had become highly prized in Paris, especially after an ambitious exhibition of ukiyo-e works at the École des Beaux Arts in the late 1880s. Vallotton also saw Japanese prints, including some by Hokusai, at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1898 where he was exhibiting a number of his own works. While Vallotton's painting output was shifting towards domestic scenes, his exposure to the Japanese art saw him simplify his compositions. So inspired, Vallotton cut his blocks lengthwise along the grain of the trunk. He also revived the "white-line" technique, whereby the woodblock is first saturated in black ink, then white lines are carved into the inked surface. In his starkly rendered images, Vallotton's figures seem to emerge from the solid mass of dense black. He would soon become the leading light in the revival of woodcut method, reinventing it as a legitimate artistic medium. The artistic focus did not meet with everyone's approval, however. "No one pays attention nowadays to anything but prints", mourned the veteran Impressionist Camille Pissarro, "it's a rage, the young generation produces nothing else".

Vallotton's growing reputation as a printmaker led to an invitation to join the newly-formed Les Nabis (Prophets) alongside artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis. The members of Les Nabis were united in their devotion to the Symbolism of Gauguin and Cézanne. They also shared in Vallotton's appreciation of Japanese art, principally the flatness of the picture surface, the simplified, abstracted forms and ornamental elements, and the use of strong lines and lurid, unnatural colours. But, while he remained close to Vuillard, Vallotton never quite fitted in with the other group members and became known as "le Nabi étranger" (the "foreign" or "strange" Nabi). Vallotton's sympathy for Alfred Dreyfus, the wrongly accused Jewish military officer in France's long-running political scandal, only strained his relationship with Les Nabis further. Yet it was due to his association with the group that Vallotton became connected with a circle of writers, critics and artists for the influential literary magazine La revue blanche; an avant-garde journal for which he became principal illustrator. Indeed, La revue blanche provided the once lonely Swiss émigré with an extended family (albeit one comprised of anarchistic revolutionaries).

Through his prestigious La revue blanche series of woodcuts, Intimacies (1897-98), Vallotton indicated that he had exhausted the theme of civilian/state power struggles and had turned his ire towards the superficial, immoral behaviour (as he saw it) of bourgeois couples. Art historian Lise Holst described how the collection offered the public and critic "something of an iconographic puzzle, one which is worth unravelling as it offers insights into both the artist and his milieu [modern Paris]". With his ten woodcuts, their black surfaces cut through by a few white lines, Vallotton interrogated the emotional lives of the Parisian bourgeoisie, touching upon the struggle between man and woman in scenes of adultery a deceit that are almost melodramatic in their execution. Such was the success of Intimacies, many commissions followed from non-French publications such as the Chicago-based Francophile magazine, The Chap-Book. When La revue blanche ceased publication in 1903, Vallotton's engagement with its close-knit Parisian artistic and literary world came to an end too.

In April 1898, Vallotton showed paintings at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard, the influential dealer who supported Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and numerous other upcoming artists. The following year, a major change took place in Vallotton's life when he married the widow, and mother-of-three, Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, who was the daughter of Alexandre Bernheim, a prominent art dealer. In a letter to his brother, he wrote: "Some great news that will really surprise you: I'm going to get married. I am marrying a lady I have known and appreciated for a long time [...] She has enough means to support herself and her children, and with what I will be able to earn, we will manage very easily. And what's more, the family will take care of the children, and I am sure will be a powerful source of help to my career. They are important art dealers".

No longer reliant on magazine illustrations for income, the critic Julius Meier-Graefe observed that "Painting was his final phase" and that his wood engraving could be effectively thought of as a "preparatory period" during which "he explored everything he now wished to incorporate into his painting". Having left his Bohemian lifestyle behind, and returned to one closer to his upbringing, Vallotton had become part of a French establishment family, the kind of which he had previously attacked, and his paintings were now populated with the characters from his new life. His new status brought with it the anticipated spike in his artistic fortunes. In 1903 Vallotton exhibited at the Vienna Secession and sold a number of paintings there. That same year, the French government bought one of his works for the first time for the Luxembourg Museum. His marriage also allowed Vallotton access to one of the most significant galleries in Paris, the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, owned by his wife's family. It bestowed on Vallotton two solo shows at which he sold a combined total of 13 paintings.

Vallotton's work was collected by the Swiss painter and patron Hedy Hahnloser who encouraged further sales and wrote his biography. Leo Stein, brother to the legendary literary salon hostess Gertrude Stein, also became a collector. Having described him as "a Manet for the impecunious". Gertrude nevertheless posed for a portrait by Vallotton, just a year after she had sat for Picasso. The author and critic James R. Mellow described Picasso's portrait as "a stunning transitional work" that overlapped "the end of his Rose Period of harlequins and circus subjects" with the "brown and somber" coloring and "sharp and angular characterization [that] looked ahead to the approach of Cubism ". Picasso may have had the higher profile as an artist but, as the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery pointed out, "in pulling Stein's head back from the picture plane and making her robe a monolithic platform for her massive head and hands, Vallotton rendered her a female Buddha [and by] the late 1920s [it was Vallotton's] interpretation of Stein as imperious, remote and ageless that became the common one ". The artist also painted his wife numerous times (usually involved in domestic activity) and by 1907 he had also found time to pen a novel, La Vie meurtrière (The Murderous Wife), published posthumously in 1930. (Vallotton also produced several unpublished plays over subsequent years.)

Late Period

In his later years, Vallotton rarely returned to social satire. After 1904, cool, detached images of nudes became his principal subject. In these works there is little painterly sensuality and the influence of Ingres resurfaces. His cold approach to his subject was often criticized. For example, a 1910 review in Neue Zürcher Zeitung, likened Vallotton to "a policeman, like someone whose job it is to catch forms and colors. Everything creaks with an intolerable dryness [...] the colors lack all joyfulness". The writer Julian Barnes wrote that, "He is a painter who, more than any other I can think of, ranges from high quality to true awfulness" and suggested the following rule of thumb applied to Vallotton's nudes: "the fewer clothes a woman has on in his paintings, the worse the result".

In spite of his seesawing critical fortunes, the French government offered Vallotton the Légion d'Honneur in 1912 which he refused (like Bonnard and Vuillard before him). Two years later, when the First World War broke out, he was considered too old to serve. Vallotton was deeply affected by reports of the devastation and loss of life and in 1915 returned to woodcuts for a series titled C'est la guerre! (This is War), his very final series of prints. At the request of the French government he toured the battlefields of the Champagne region and painted its destructive effect on civilian buildings and churches. In 1917 he also published an essay, "Art et Guerre" ("Art and War"), in Les Écrits nouveaux in which he described the challenges of capturing the realities of the war through art.

In his final years, and fighting ill health, Vallotton became more withdrawn from public life. He continued to paint, however, focussing now mainly on landscapes and still lifes. Created in the studio from sketches and photographs, the landscapes possess an almost hypnotic tranquillity. "I would like to be able to re-create landscapes only with the help of the emotion they have provoked in me," the artist wrote in 1916, "a few large evocative lines, one or two details, chosen with no thought for the exact time or light". The French author Mathias Morhardt added, "In his interpretation of nature, he looked for its subtlest aspects: soft colouring and concealed melancholy". His print-inspired landscape, The Dordogne at Carennac, in the south-west of France, would prove to be one of his last finished works. Vallotton died, one day after his 60th birthday in 1925, following cancer surgery.

The Legacy of Félix Vallotton

Largely forgotten, or at least side-lined, from the grand narrative of modernist art, Vallotton nevertheless made a significant contribution to the visual record of life during the turn-of-the-century in Paris. In this respect, his prints, with their stark black-and-white graphic approach, can be likened to the impact Aubrey Beardsley was making on Bohemian London. Vallotton's story-telling approach, with its cartoon-like characters, are perhaps pre-cursors to European bande desinée (drawn strips) such as Tintin or the more recent political graphic novels such as Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis or Art Spiegelman's Maus.

In Vallotton's cool and detached observation of life, and the psychological disquiet of his subjects, similarities can be made to the paintings and prints of Edvard Munch, Edward Hopper and even the Surrealist René Magritte. There are also strong resonances with the cinematic vision of German Expressionist Fritz Lang, with his striking use of chiaroscuro shadows, and Alfred Hitchcock's, cool domestic interiors and foreboding spaces which he filled with mysterious and sinister characters. More recently, director Wes Anderson and his partner Juman Malouf have been inspired by Vallotton to create flattened colour schemes for their highly idiosyncratic set designs. Art critics and historians have given Vallotton credit for reviving the moribund art of woodcut, which was adopted from 1905 by Expressionist artists such as the Germans Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Indeed, since Vallotton's intervention the status of woodcut has become accepted as a legitimate medium for modern artists to explore.

Influences and Connections

-

![Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec]() Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec -

![Gertrude Stein]() Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein -

![Ambroise Vollard]() Ambroise Vollard

Ambroise Vollard - Jules Joseph Lefebvre

-

![Pierre Bonnard]() Pierre Bonnard

Pierre Bonnard -

![Édouard Vuillard]() Édouard Vuillard

Édouard Vuillard - Félix Jasinski

- Charles Maurin

-

![Expressionism]() Expressionism

Expressionism -

![New Objectivity]() New Objectivity

New Objectivity - Bande desinée

Useful Resources on Félix Vallotton

- Félix Vallotton: The Nabi from SwitzerlandBy Nathalia Brodskaïa

- Félix VallottonBy Dita Amory, Philippe Buttner, and others

- Félix Vallotton: Fire Beneath the IceBy Marina Ducrey

- Félix Vallotton: Les paysages de l'émotionBy Bruno Delarue and Michel Pastoureau

- When Gertrude Stein Toured AmericaSmithsonian Magazine, October 13, 2011