Summary of Pattern and Decoration

The Pattern and Decoration (P&D) movement emerged as a vibrant counter-response to the austerity of Minimalism and the historical dismissal of craft and Feminist art. It was deeply intertwined with feminism, challenging art historical hierarchies that devalued women's work and non-Western traditions. P&D artists worked across painting, textiles, ceramics, installation, and performance, creating environments where ornament was no longer peripheral but central, insisting that beauty, pleasure, and decoration could carry intellectual, political, and cultural weight.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Rather than abandoning painting (which critics in the 1970s were declaring dead), P&D redefined it - moving beyond the flat canvas to include shower curtains, bed sheets, wallpaper, ceramics, and even furniture. These works blurred painting, sculpture, and architecture, producing immersive patterned environments that anticipated installation art as a mainstream genre.

- Decades before "global contemporary art" became a curatorial mandate, P&D artists deliberately integrated Islamic tilework, Japanese textiles, Celtic metalwork, Oaxacan ceramics, and African motifs into their compositions. This wasn't mere citation; it was a structural argument that the Western canon must expand, making cultural multiplicity and hybridity foundational to art practice.

- In essays like Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture, P&D artists directly critiqued the Modernist obsession with purity and singularity. By embracing what Amy Goldin called the "promiscuity" of pattern - its ability to exist across cultures, mediums, and histories - they offered a pluralistic model of art that destabilized the rigid hierarchies of Minimalism and Conceptualism.

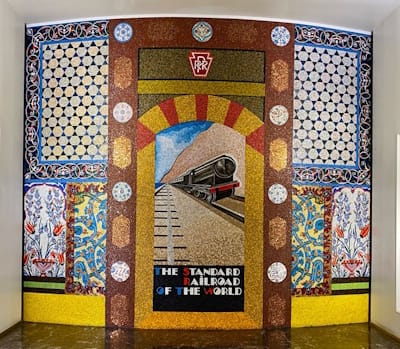

- Through commissions like Joyce Kozloff's subway mosaics and Valerie Jaudon's architectural murals, P&D dissolved the barrier between art and everyday life. Their public installations democratized access to high art while demonstrating that decoration could transform civic space - something that influenced later waves of socially-engaged and site-specific art.

Artworks and Artists of Pattern and Decoration

Sixish

This quixotic work uses thick layers of paint that resemble corrugated carpet in its center rectangle, framed by orange flame shapes that lick like tongues at the edges of thick grey frosting. Evoking picture frames, sheet cakes, and carpet, the work alludes to the realm of the domestic and ordinary, while simultaneously playing with those allusions. Viewers experience a kind of cognitive dissonance, as attempts to categorize the piece collapse under its contradictory signals. Even its medium, acrylic on wood, performs as trompe-l'œil: the surface suggests an assemblage of found or readymade objects rather than a meticulously painted construction. The technique Carlson used was also innovative, as the Woodmere Museum wrote, "Carlson used a cake decorating tool to pipe the orange outlines...[and]...has created a painting that has become an object, not as an imitation or reference to an object."

Carlson said that she was inspired by "funky Surrealist techniques of American art," in using patterns to disrupt aesthetic and societal expectations. The Virginia Museum of Fine Art noted, "Carlson quite literally embodied the definition of 'women's work,'" embracing decorative strategies traditionally relegated to the domestic sphere. At the Philadelphia College of Art where she taught, she became a leading feminist advocating for the aesthetic power of decorative impulses to subvert and challenge patriarchal hierarchies. She also created a number of installation works, where she used or created wallpaper to create unexpected interior spaces, by letting pattern dominate rather than serving as decorative background.

Acrylic on wood - Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia

Angel Feet

Angel Feet (1978) is a triptych that transforms domestic ornament into a monumental and lyrical field of pattern. Against a radiant blue ground, the panels bloom with gold floral motifs and large blossoms in soft whites and pinks, their generous petals floating weightlessly on vertical black stems. The central panel emphasizes expansiveness: the wide intervals and subtle diagonals of the stems allow the flowers to hover like abstract forms, while the flanking panels recall leaves or feathers on paler blue grounds, extending the sense of uplift and airiness.

In this work the artist represented the motifs and the wallpaper of his grandparents' house, a place where he said, "ornamentation was everywhere...My grandparents refused to live in bleak empty rooms and decorated everything." The title also evokes warmth, a sense of blessing, honoring his deceased grandparents, and acknowledging the origins of his art, as he said, "The need to decorate is one of naturalness and optimism. It is what culture does; enriches our lives. And, in fact, culture is the 'decoration of society.'"

Although he began his career as a minimalist painter, Zakanitch deliberately shifted away from austerity, helping to establish and propel the Pattern and Decoration movement. Angel Feet epitomizes this radical departure. Instead of rejecting ornament as trivial or "feminine," the work monumentalizes it, positioning decoration as a serious, even essential, aesthetic language. Critic Catherine Wagley has noted that P&D artists made "a decisive shift in style - a deliberate attempt to address limitations and rigidities in the Modern Art canon." For Zakanitch, this meant occupying the fertile ground between abstraction and representation, where ornament could be both memory and invention, both cultural marker and artistic rebellion.

Acrylic on canvas - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Barcelona Fan

This large fan, twelve feet wide by six feet tall, reinterprets a handheld fan, primarily associated with women and the cultural traditions of courting and gender performance, into a heroic form, its bold patterns flared out. The work is a femmage, a term the artist coined to describe her collages, constructed of various fabrics hand-painted with patterns, that evoked the domestic world and women's labor. The symmetrical shape is composed of twelve alternating ribs, their gleaming patterns suggesting the mother-of-pearl used in the flamenco fans of Barcelona, and twelve leaves of brightly colored floral motifs. The patterning creates a dynamic sense of rhythm. Schapiro began experimenting with the fan shape in 1978 and said the motif seemed to "reveal the unfolding of woman's consciousness," serving as "an appropriate symbol for all my feeling and experiences about the women's movement. That's a very ambitious notion: to choose something considered trivial in the culture and make it into a heroic form."

A leading figure of the Feminist Art movement, Schapiro was also a founder of the Pattern and Decoration movement, as her interest in pattern and decoration became a way to challenge not only the hierarchies of gender but the hierarchies of the artistic world. Accordingly, her Pattern and Decoration pieces used "feminine" materials to create "feminine" objects, such as fans or hearts, on the heroic scale, as seen in the eight- by nine-foot heart-shape of Heartland (1985). As the Metropolitan Museum noted, "In so doing, Schapiro and others expanded the boundaries of modernist abstraction and tested the rigid hierarchy dividing high and low as well as the fine and applied arts. For her part, Schapiro sought early on to create 'art out of women's lives' and to validate 'the traditional activities of women,' a gesture equal parts aesthetic and political."

Art historian Anna Katz lauds Schapiro's long-term, though often unacknowledged, influence on subsequent artists. As Katz noted, "Although she is unheralded as the source, the influence of Schapiro's subjective approach to forms of decoration can be identified today in a remarkably diverse group of artists who continue to find inspiration in her embrace of artistic practices outside the art historical canon. ... This juxtaposition of historic and contemporary work brings into critical focus the tremendous role Schapiro's femmages played in the reframing of craft and decoration, while shining a light on the way artists today, both distinguished and emerging, continue to approach the decorative as a language of abstraction tied to the personal and the political."

Fabric and acrylic on canvas - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

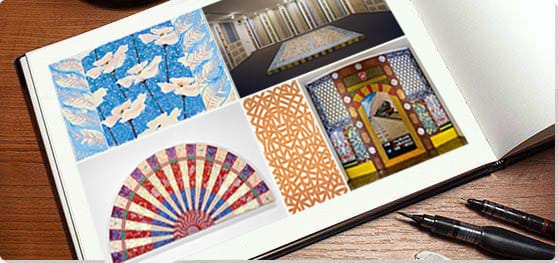

Joyce Kozloff

Described by art critic Carter Ratcliff as, "One of Kozloff's most famous works," this interior was first exhibited in 1979 in New York City and announced Kozloff as a pioneer in the Pattern and Decoration movement's expansion into installation art. The center of her piece is the floor, its rectangular shape, constructed of ceramic hexagonal and star-shaped tiles, a thousand of them, each hand-painted, while the surrounding walls are composed of hanging fabrics, some of silk or silk on rice paper. Both the hand-painted tiles and the wall hangings, silkscreened or lithographed with various patterns, draw upon what Kozloff called her "personal anthology of the decorative arts," motifs taken from a wide range of cultures and styles. At the time of the initial exhibition, art critic Jeff Perone said of the piece, that "the whole overwhelms at first in a dazzling array of color and pattern. A case could be made for the importance of its overall effect, but for me, her art really comes to life close up. You have to get near to see the tiles, to see what they're made of, how they're painted, how they're different from one another, where their pattern-units come from. You have to get down in a prone or prayerlike position on the floor to savor the complex collage of cultural material."

Kozloff described her artistic evolution toward installation art as beginning when, "I found myself increasingly uncomfortable with the discrepancy between the way I talked about my work and the way I saw the paintings themselves. At that time there was much discussion about breaking down the hierarchies between 'high' art and crafts. And yet, I was merely using 'low' art sources as subject matter for...paintings." As a result, as she said, "I decided to move onto the walls and to decorate a room - that is, an environment in which the ornament would be literal and physically palpable." As art critic Carrie Rickey wrote, "An Interior Decorated is where painting meets architecture, where art meets craft, where personal commitment meets public art."

The work also raises the question of appropriative art that has challenged the movement's use of pattern devoid of culture context. Kozloff described the floor as "The most complicated and ambitious" part of the project, as she noted, "I've painted motifs from many traditions onto these tiles: American Indian pottery, Moroccan ceramics, Viennese Art Nouveau book ornament, American quilts, Berber carpets, Caucasian kilims, Egyptian wall paintings, Iznik and Catalan tiles, Islamic calligraphy, Art Deco design, Sumerian and Romanesque carvings, Pennsylvania Dutch signs, Chinese painted porcelains, French lace patterns, Celtic illuminations, Turkish woven and brocaded silks, Seljuk brickwork, Persian miniatures and Coptic textiles." However, Kozloff has also been remarkably transparent and open about both her sources and the collaborative efforts involved in her work. She notes in considerable detail how the wall hangings "were silkscreened at The Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia....Twenty screens were used for each piece. Their designs are of Islamic and Egyptian derivation, printed in a wide variety of colors." First shown at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, the piece was redesigned for each subsequent exhibition, in order, to produce "a new Decorative Art in the human space where they meet," as noted by Jeff Perone.

Ceramic tiles and pilasters, silkscreen silk, lithographs on silk on rice paper - Private Collection

Ingomar

With its interlacing patterns and lines of burnished copper, this work approaches abstraction with its exploration of flatness, while simultaneously evoking Celtic metal work or the patterns found in Islamic architecture. As art historian Arthur C. Danto wrote, "Jaudon's paintings explore the perceived boundary between ...two approaches to art, combining the beauty and intricacy of decorative design with the theoretical processes that underpin abstract painting." Yet, Jaudon carefully creates a unique pattern, found only in this work, even as the viewer may look for a predictable pattern in the repetition of triangular motifs interwoven with repeating half circles, in the dense but intricate overlaying that completely fills the pictorial plane.

The work's title is taken from the name of a town in Mississippi, the state where Jaudon grew up. As Danto wrote, the artist "titled her paintings made in the 1970s after cities in her home state of Mississippi ...This random naming system was intended to deter the perception of the paintings as descriptive or narrative." Jaudon has continued to work in what art critic Christopher Knight described in 2016 as "her familiar motif of wide but intricate two-dimensional interlaces painted in oil on linen. A seeming simplicity gets more complex the longer you look." He further notes how, "Her rhythmic interlaces are somewhere between elaborate calligraphy and simplified pictograms," and "draw on a host of dazzling sources... These she bends to Western traditions of formal abstraction. Suddenly, our vaunted modernity seems of a playful piece with ancient multicultural practices."

Oil and metallic paint on canvas - National Museum of Women Artists, New York

Fairies

Painted on linen with a playful red fringe on the top and bottom margins, this work's garden motif interweaves extravagant red and blue flowers with the faces of feminine fairies, pensively looking through the foliage, as if springing up from the soil. Some of them wear floral headdresses, and the black dots of their eyes resemble the black dots of the orange stamens that erupt from the blossoms, while their eyebrows resemble the petals of flowers. The patterning creates a kind of syncopated rhythm. Evoking the work of Matisse, Kushner's use of red and blue primary colors and his contrast of the fleshy flowers with the more sketch-like faces of the fairies creates a sense of unexpected presence, as the decorative intensity of the flat surface takes on a kind of depth.

Kushner grew up in Pasadena where he began making art as a child, as his mother was a successful Abstract Expressionist painter. However, it wasn't until later that he discovered his own sense of artistic vocation, one informed by his love for gardening and his interest in textiles. Amy Goldin was his mentor, and as a student he travelled to Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan where they studied and collected the textiles of the various cultures. Upon his return to the United States, his interest in the textiles led to his becoming an expert restorer and eventually led to a complete reevaluation of his aesthetic values. As he said, "I want everybody to see how fantastic these decorative traditions are. That I didn't know anything about with my formal art history. Those Suzanies, the embroidered Uzbek things are transcendent. And someone spent a year making it. But we put it down here because, number one, they were anonymous. Number two, they were women, and number three, they were Uzbek."

Kushner became a founding member of the Pattern and Decoration movement, and as Our Choices Art noted his work in the early 1980s focused "on figures and unstretched canvases where color combinations are carefully orchestrated to elicit a sensory experience, akin to opening a long-forgotten box and encountering a familiar yet elusive scent." His subsequent work has evolved since, expanding into installation work, performance, and public art, but his aim has remained the same, as he said in 2023, "The spiritual for me has always been really, really, really important. I want my work to uplift you. Flat simple statement."

Acrylic on cotton - Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

Untitled (Shower Curtain)

An ordinary shower curtain transforms by splashes of vivid color and fluid forms into a sensuous exploration of color, exemplifying how, according to arts writer David Ebony, "hedonism prevails in P&D works... decoration is paramount and excess is a virtue." Designed for the bathroom of gallerist Holly Solomon, who launched Pfaff's career with a 1980 solo exhibition, this piece surpassed its supposed intent, becoming one of the more influential pieces of the artist's oeuvre, as seen in the inventive use of shower curtains by contemporary artists such as Lisa Hoke and Rochelle Feinstein.

At the time of Pfaff's 1980 exhibition at the Holly Solomon Gallery, art critic Wade Saunders noted, how "reviewers have labeled Judy Pfaff's work ... 'quirky,' 'kooky,' 'loony' 'exuberant,' 'rambunctious,' 'rowdy' and 'zany.'' These words are accurate about appearance, but inaccurate about consequence or importance...Pfaff has acutely, if playfully, undercut the still-felt separations between painting and sculpture, and between gallery art and theater." Ebony also noted the artist's intent, "Patterning, layered fabrics, sequins and glitter, and high-key paint tones abound in the work, while furniture, wallpaper and decorative objects are elevated to esthetically lofty positions they never held before... A serious socio-political agenda further underlies the glitzy surfaces of P&D works - a visual manifesto centered on feminism, and an effort to overturn the traditional male-dominated view of art history."

Mixed adhesive plastics, plastics, paint and paper collage - Private collection

Formidable

This work combines four vertical strips of bedsheets, in varying widths and lengths, each painted in different colors and patterns to create a whimsical and disconcerting rhythm. Alluding to domestic patterns and washing drying on a clothesline, the patterns are both decorative, like the somewhat garishly colored jugs on the left, and chaotic, as seen in the hand decorated in red, its swirling pattern also resembling the face of a psychedelic rabbit. As MacConnell said of his work, "The idea of taste is central to my idea of decoration. Decoration doesn't have to be tasteful. In fact, most successful pieces in terms of being decorative are things which are not tasteful. And so, there's this irony that I like playing with."

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles described MacConnell as "A key figure in the pattern and decoration...movement ... [as he] ...purposefully sampled and cross-pollinated everyday kinds of ornamentation in his work, including Hawaiian shirts, tablecloths, chinoiserie décor, and Southeast Asian wall hangings. He thumbed his nose at Western art's centuries-old tradition of valuing fine arts over decorative arts and proposed a new type of painting that embraced discredited ornamental patterns." The technique of painting is also disrupted, as he replaces the usual taut surfaces of canvas or board with loose pliable pieces of fabric. As MacConnel said, "Pattern to me is a vehicle," a vehicle which he further described as "nonhierarchal...much more chaotic...open to different voices."

Acrylic on cut and sewn bed sheet - Whitney Museum, New York

N.Y.C./B.Q.E.

By the mid-1980s, Pfaff had become a pioneer in the installation movement, as shown in this work created specifically for the 1987 Whitney Biennial. The piece utilizes a dazzling array of ordinary objects and materials to create a sense of the lively and chaotic exuberance of New York City, along the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Objects, such as lawn chairs and tables evoking back yards, or awnings evoking storefronts, are combined with various metal or laminate discs and balls, hand-painted in vivid colors, all erupting from a wall painted in a black, white, and yellow brick pattern, that is continually broken as if by an exuberance it cannot contain.

Everything seems upended, as if tossed into the air, a kind of floating delightful panoply. As artist Elliot Green wrote, "One of the most striking aspects for me about Pfaff's work is the use of air between the various elements. She encompasses open spaces within the expanding structure, which seem to 'capture' the air. They become the pathways between materials." Green notes that in response to his observation Pfaff replied, "You know, that was my argument with the way sculpture was defined in the 1970s. At that time, it was all about mass - it was weight - the integrity of the object. Perhaps because I come from a painting background, I felt that the opposites were better - no gravity at all would be ideal, and the effect would be more like you're swimming, and things are just floating."

At the time of the Whitney Biennial, Pfaff felt that the exhibition had been something of a failure, as she said, "At the Whitney, the last big clunker show I had, I was so wrong in that arena. I was the bull in the china shop and usually there are lots of bulls in that place. The show was a cooled out, carefully curated, chosen few who really made pretty, elegant things. You put me next to work that is highly resolved, and I look like a buffoon. It's only when the mood is experimental that it looks right." Nonetheless, her career has continued to thrive, and she is a leading installation artist today as seen in her 2024 exhibition Real and Imaginary at the Wave Hill Glyndor Gallery which art critic Faye Hirsch called "a teeming world of natural and artificial abundance."

Painted steel, plastic laminates, fiberglass, wood, paint, lawn furniture, awnings - Artist's collection

Beginnings of Pattern and Decoration

In 1975, a small circle of inventive artists gathered at Robert Zakanitch's Manhattan home. Among them were Miriam Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff, and Tony Robbin - each already established in different artistic arenas. Schapiro was celebrated as a pioneer of the Feminist Art movement; Zakanitch had worked as both an illustrator and a minimalist painter; Kozloff was known for painting and printmaking; and Robbin had made his mark as a geometric abstractionist. Despite these diverse backgrounds, they shared a moment of questioning. Together, they began dismantling long-standing hierarchies that separated so-called "high art" from decorative arts.

Kozloff later observed that the network which seeded this new bicoastal movement - Pattern and Decoration (soon shortened to P&D) - had a "big UCSD connection," since both Schapiro and Zakanitch had taught at UC San Diego alongside Amy Goldin, the art critic and theorist whose writings profoundly shaped P&D's foundations.

The artists were, in part, rebelling against the austerity of Minimalism, which had dominated the art world since the mid-1960s, and against the critical disregard often directed toward Feminist art. As critic David Ebony noted, "P&D offered an effective countermeasure to the prevailing - and often stifling - dictates of Minimalism, which had ruled the art world with patriarchal authority. A serious socio-political agenda further underlies the glitzy surfaces of P&D works - a visual manifesto centered on feminism, and an effort to overturn the traditional male-dominated view of art history as well as Western cultural chauvinism."

Drawing from feminist practices and global traditions, Pattern and Decoration embraced motifs from Turkish rugs, Moroccan tiles, Celtic metalwork, Oaxacan ceramics, Japanese textiles, and more. These sources, long dismissed as "craft" or "domestic handiwork," became both inspiration and subject. P&D artists worked across painting, textiles, ceramics, wallpaper, clothing, interior design, sculpture, installation, and performance, deliberately blurring boundaries between art and life.

From its inception, the movement resisted stylistic uniformity. Valerie Jaudon recalled: "The decorative has always been important for me... Even at the beginning of P&D, our first group show, everybody seemed to know what it was about - but everybody's idea was different. That's why it was so confusing. Of course, the word 'decorative' was so loaded with associations... What the decorative calls into question, of course, is the idea of the aesthetic itself."

As art historian Ben Johnson observed, "Pattern and Decoration did not distinguish between background and foreground, nor did it emphasize specific aspects of the composition. Rather, much like the abstract painting of its time, it covered the canvas from edge to edge in an all-encompassing design. At the outset of the movement, P&D artists reacted against the severe lines and restrained compositions of minimalism, yet they often retained the same 'flattening grid' that Minimalist painters employed."

Artistic Influences

The Feminist art movement was a primary influence on Pattern and Decoration. In 1971, Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago established the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, followed the next year by Womanhouse, a landmark performance and installation space. Womanhouse became a hub for emerging artists, fostering collaboration, experimentation, and the development of new aesthetic languages.

Later, Schapiro and artist Melissa Meyer coined the term femmage, a fusion of "feminine" and "collage," to describe works that combined traditional collage and assemblage with materials and techniques historically associated with women.

Schapiro and Meyer's essay, "Waste Not Want Not: An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled - FEMMAGE" (1977-78), became foundational to both Feminist art and P&D. They defined femmage as a "word invented by us to include all of the above activities [collage, assemblage, decoupage, and photomontage] as they were practiced by women using traditional women's techniques to achieve their art... activities also engaged in by men but assigned in history to women." The essay challenged the erasure of women and non-Western artists from the history of collage, noting: "Published information about the origins of collage is misleading. Picasso and Braque are credited with inventing it. Many artists made collage before they did...When art historians mandate these beginnings at 1912, they exclude artists not in the mainstream. Art historians do not pay attention to the discoveries of non-Western artists, women artists, or anonymous folk artists."

Curator Elissa Auther has highlighted Schapiro's reappropriation of the decorative as a feminist visual language." By incorporating thread, ribbon, beads, feathers, and other elements related to women's domestic labor and handicraft, Schapiro created frames within her compositions out of materials conventionally relegated to the margins. As Auther explains: "What is normally considered merely supplemental, secondary, or peripheral to a work of art - the frame, ornament, or decoration - is now at its center."

Scientific Influences

Just as Pattern and Decoration drew power from feminist strategies of revaluing the decorative and the domestic, it also absorbed energy from the scientific imagination of the era. At its core, P&D was about recognizing pattern as a universal language - whether woven into a quilt, traced across a ceramic tile, or revealed by mathematics and biology. Artists began to see pattern not only as cultural expression but also as a key to understanding the structures of existence itself.

Architect and futurist R. Buckminster Fuller was especially influential in this regard. Fuller celebrated the scientific importance of patterning, insisting that "A pattern has an integrity independent of the medium by virtue of which you have received the information that it exists." He also argued that pattern was an essential element of human existence, as he added, "Each individual is a pattern integrity. The pattern integrity of the human individual is evolutionary and not static." His best-known invention, the geodesic dome - an intricate hemisphere built from interlocking triangles - became a powerful symbol of this philosophy. From the U.S. pavilion at the 1967 Montreal World's Fair to Spaceship Earth at Disney's EPCOT (1982), Fuller's domes embodied both futuristic optimism and a deep trust in the language of geometry.

Fuller's designs and ideas, including his enthusiastic belief in human progress, were widely popularized and had a notable impact on artists and intellectuals, encouraging multidisciplinary explorations. As art historian Rebecca Skafsgaard Lowery points out, many artists of the 1970s studied DNA, fractals, and other patterns that seemed to underlie all living systems. For P&D artists, science offered both inspiration and validation: if the natural world itself was structured by repeating forms, then decoration was no longer superficial - it was fundamental.

Tony Robbin, for example, extended this inquiry into painting. He experimented with visualizing the fourth dimension through shifting layers of geometric pattern, producing canvases that seemed to vibrate with infinite depth. His works often drew from cross-cultural sources, such as his Japanese Footbridge (1972), which sought to capture the layered spatial complexity he admired in Oriental art. In this way, P&D stood at the intersection of feminism, science, and global traditions - each demonstrating that pattern was never merely ornamental, but a key to how we see, live, and imagine.

Holly Solomon Gallery

An aspiring stage actress, the glamorous Holly Solomon, was also profoundly interested in contemporary art, and she became a Pop Art icon when Andy Warhol created her portrait in 1966. She and her husband, Horace, began as enthusiastic collectors and supporters of Pop Art and founded the 98 Greene Street Loft, a work and performance space for artists, writers, and actors. After the Loft closed, the couple established the Holy Solomon Gallery in 1975 in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan. Focusing on contemporary art, the gallery became "the most successful commercial gallery in actively promoting P&D," as noted by art historian Anna Katz.

As art critic Karen Chernick wrote, "Few gallerists were willing to take a chance on the growing number of artists producing highly decorative pieces as a reaction against the severity of Minimalism."

Most of the movement's leading artists, including Valerie Jaudon, Miriam Schapiro, Kim MacConnel, and Robert Kushner, exhibited at the gallery. For instance, Judy Pfaff's career was launched by her 1980 solo exhibition at the gallery, and the artist was to acknowledge Solomon's importance in later works like her mixed media sculpture Honey Bee, for Holly Solomon (1987). Robert Kushner said in 2014, "You can't imagine how supportive she was, always telling artists, 'Do it.' With Holly, who was interested in whatever was new and different, I didn't have to make excuses for using glitter." In 1989 Holly Solomon subsequently also founded the Arts Video News Service, which featured art reviews, exhibitions, and interviews, as she continued to promote the work of P&D artists into the 21st century.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Teaching at the University of California in San Diego alongside Schapiro, Amy Goldin influenced and mentored both Kim MacConnel and Robert Kushner. An important critic, she went on to create some of the early theoretical foundation for P&D, as she attended the earliest meetings of the group, exploring her own interest in folk art and pattern and decoration. Additionally, Goldin's interest in Islamic aesthetics became a major inspiration for P&D artists, including Jaudon, Kozloff, Kushner, and others.

In 1975, she published her essay "Patterns, Grids, and Painting" in Artforum, which curator Anna Katz later described as "a foundational text in the P&D movement." Goldin argued that pattern, by its very nature, rejects the values of singularity, purity, and absolute precision so prized in Modernism. Katz highlights Goldin's striking use of the word "promiscuous," noting that she understood it as conceptually generative for artists working with pattern. For Modernists, patterns were considered superficial - merely surface decoration, something non-essential that should be stripped away in the pursuit of purity. In contrast, P&D artists embraced this so-called "promiscuity." Patterns were not bound to a single medium or material; they could appear in a rug, a garment, or the mosaic dome of an Islamic mosque. This very impurity - pattern's refusal to be contained - was precisely what gave it power, and what P&D artists sought to harness.

In 1978, Valerie Jaudon and Joyce Kozloff published their essay "Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture" as a witty response to criticism of the P&D movement. In it, they mocked the idea of purity in art, calling it just "a newer, more subtle way for artists to elevate themselves." They argued that this pursuit of purity only reinforced the myth that high art was reserved for a select few, and instead pushed for dismantling those long-standing biases in art history.

Genres

Painting

Although Pattern and Decoration drew heavily from the materials of craft and applied arts, painting remained at the heart of the movement - at a time when many critics were declaring "the death of painting." As Karen Chernick noted, "the Holly Solomon Gallery...also refused to accept the prevalent idea that painting was dead, exhibiting Pattern and Decoration artists who were painting unapologetically representative and decorative canvases."

Instead of abandoning painting, P&D reinvented it. Color and pattern became central subjects, celebrated in their own right. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts noted that "Like their forbears the abstract expressionists, as well as their contemporaries the minimalists, P&D artists employed a flattened paint surface without a foreground or background." But they expanded the field of painting by working on unexpected supports - sheets, bedspreads, paper, shower curtains. Even ceramic tiles were hand-painted, each one unique.

Contemporary art critic Jerry Saltz notes that the movement "reinvented painting, opened it up, made it into many mediums at once and many techniques. This when - just as women were getting to show more and wanted to show their paintings, the scaredy-cat male art world said, 'Sorry, no more painting.' Hah!"

Installation Art

Many of P&D's leading artists, including Miriam Schapiro, Cynthia Carlson, Judy Pfaff, Valerie Jaudon, Tina Girouard, Robert Kushner, and Robert Zakanitch, became known for their innovative and ambitious installations. In so doing, the movement emphasized the transformative powers of decoration and pattern to reconfigure space, as seen in Cynthia Carlson's Installation (1980) in Cincinnati, Ohio, where the walls of a room were covered in red wallpaper, painted with a leaf motif moving at diagonals from left to right, interweaving with attached 'tiles', painted parallelograms also with a leaf motif, arranged on the opposing diagonal. The piece created a kind of inner confrontation for the visitor, caught between the evocation of nature in the dynamic lines of leaf motifs and the somewhat claustrophobic effect of the red interior. Joyce Kozloff's installations often evoked Islamic and other cultural motifs with her use of patterned ceramic tiles combined with hangings of silkscreen silk as seen in her An Interior Decorated (1979-80). By the mid-1980s Judy Pfaff had become a leading installation artist, employing ordinary and diverse objects - such as lawn furniture, lattice, signs, Formica, and paneling-to create artworks specifically designed for the exhibition space, as seen in her Gu Choki Pa (1985) for an art center in Toyko.

Public Art

A number of P&D artists were commissioned to create public works, of whom the most successful were Joyce Kozloff and Valerie Jaudon. As art critic Nancy Stapen wrote of Kozloff, public art was "a logical extension for an artist who had progressed from painting, through an exploration of printmaking and craft forms, to an ever more encompassing multimedia environmental art. Between 1979 and 1985 she completed five major commissions, including mosaics for subway and train stations in Wilmington, Buffalo, Philadelphia, and Cambridge, and for the International Terminal of the San Francisco Airport." The art critic Jeff Perone in his article "The Decorative Impulse" (1979) had written P&D was driven by "a constant attempt ...to drive art out of its antisocial tower and back into the everyday world." These public works also evinced P&D's inventive techniques, for instance, using ceramic tiles that were hand-painted, combined with more traditional forms of painting on canvas. Valerie Jaudon's Trio (1998) resembles tile or metalwork but is made of three canvases, painted with oil, metallic pigment, and resin, arranged on three levels in the Citicorp Building in New York. Joyce Kozloff's Homage to Frank Furness (1984), used ceramic tiles for the walls and entrance of the train station in Wilmington, Delaware. Kozloff joined the Arts/Industry program in 1986. As the program noted, she did so "with the express purpose of producing ceramic tiles for a commission at Detroit's Financial Center People Mover Station. Prior to that, she had been executing commissions such as these in her home studio. As an Arts/Industry resident, she had access to the Kohler Co. materials and production facilities to create the components for this installation."

Performance Art

A number of P&D artists created performance pieces; as art critic David Ebony wrote, "Performance and video were also embraced by P&D - just so long as the subject matter and presentation were unapologetically uninhibited, and aimed toward a radical redefinition of beauty, as in works by Robert Kushner and Tina Girouard." Kushner's performance Mask of Monuments, involving a number of participants, some predominantly nude and others dressed in his textile costumes, debuted at the Holly Solomon Gallery in 1972. Subsequently, he created the Persian Line I performance, which debuted at The Kitchen in New York City in 1975, and then Persian Line II at the Solomon Gallery. His costumes and textiles evoked the intricate patterns of Turkish kilims (woven tapestries or rugs) that had such an impact upon his artistic evolution when he had first encountered them as a young man.

Tina Girouard's innovative work was often overlooked, particularly as she left New York for her home state of Louisiana following the loss of her studio to a fire. Additionally, as contemporary critic David Wu noted, "One gets the feeling that Girouard's work only occasionally chose to congeal itself into anything recognizable conventionally as 'art,' instead lingering in a kind of preformed state of collaborative and co-produced 'work.'" Anna Katz described Girouard's video Maintenance III (1973) as "a particularly striking example of a feminist artwork within a timely political context. The performer is the artist herself, but you never really see her face. It's a tightly cropped image of her you see throughout the approximately 30-minute video in which Girouard 'maintains' a set of floral-patterned chiffon fabrics that she calls Solomon's lot after the uncle who gave them to her. She is shown sewing them, folding, washing, ringing, and rinsing them."

Later Developments - After Pattern and Decoration

As Anna Katz noted, P&D "enjoyed a moment of enthusiastic critical reception, commercial success, and institutional recognition in the mid- and late 1970s. There were exhibitions throughout the U.S. and in Europe." Though, she added, "By the early 1980s, it seems that P&D had been eclipsed by Neo-Expressionism." P&D was met by critical dismissal, in part because of its emphasis on celebration, rather than the ironic detachment that attended Neo-Expressionism. At the same time, the historical bias against craft and women's "work," often categorized as kitsch, led to critical devaluation. As New York Times critic Holland Cotter wrote, "Art associated with feminism has always had a hostile press. And there was the beauty thing. In the Neo-Expressionist, Neo-Conceptualist late 1980s, no one knew what to make of hearts, Turkish flowers, wallpaper, and arabesques."

The 21st century has seen a notable rediscovery of P&D, bringing exhibits, interviews, and critical attention to the movement's leading artists, many of whom have continued to explore their interest in pattern. The Hudson River Art Museum's 2008 Pattern and Decoration: An Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975-1985 played an early role in reviving the movement. More recently, in 2019, Anna Katz, curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, published With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985. Simultaneously her curated exhibition, mounting a large survey of P&D works, opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

International critical and curatorial interest in P&D has also been resurgent in recent years, leading to major exhibitions in Geneva, Aachen, Vienna, and Budapest in 2018. As art critic Catherine Wegley wrote, "This surge in exhibitions is significant because, from 1986 until the early 2000s, hardly even any minor exhibitions featured P&D as a movement, and 20th century art histories largely fail to mention it."

It should also be noted that, concurrent with this revival, works by other artists not usually linked to the movement, such as Lucas Samaras, Frank Stella, Lynda Benglis, and Faith Ringgold, have been included in P&D exhibitions. Reviewing the exhibition With Pleasure, Carter Radcliff noted "By including Ringgold, an artist not usually linked to Pattern and Decoration, Katz suggests that the movement has no firm boundaries, hence there is no point in trying to establish a P&D canon - and good reason to dismiss the canon-making project entirely." Yet, Katz herself is perhaps aware of certain criticisms of P&D, such as Roberta Smith's implication that the movement excluded artists of color. As Anne Swartz noted, Katz's exhibition "amplifies P&D's parameters, speaking to the current zeitgeist of inclusionary politics by noting significant contributions by artists not typically discussed in the context of P&D."

Anna Katz notes the influence of P&D on younger artists, including Jeffrey Gibson and Sanford Biggers. As she added, "The rise in ceramics as a prominent art form can also be linked to P&D. I am a little reluctant to name names, but here in Los Angeles, consider the ethos of someone like Laura Owens, who has invested her painting with a nonhierarchical visual vocabulary; or Rebecca Morris, who works in an abstract tradition that challenges conventions of taste and sensibility. Aside from those examples, even when looking at the work of young artists today, just out of school, I see... so many allusions to decorative and ornamental painting."

This includes Kira Nam Green, a Korean American painter whose work blends layered patterns, ethnographic imagery, and meticulous realism to explore themes of feminism, beauty, and power; Diana Guerrero-Maciá, whose hybrid "unpainted paintings" merge fabric cutwork, collage, stitching, and dye, challenging the boundaries between high art, craft, and design; Judy Ledgerwood, known for her exuberant, patterned abstractions; Anna von Mertens, who uses traditional quilting techniques infused with data-driven patterns to craft textile pieces that weave science, time, and craft into one; and Jen Stark. whose hypnotic works in paper, sculpture, and installation layer psychedelic patterns and fractal geometry into colorful mandala-like forms. Numerous other contemporary artists are mentioned for their dynamic use of pattern in both abstract and figurative work such as Kehinde Wiley, Mikayla Thomas, Hope Gangloff, Philip Taaffe, Sarah Applebaum, and James Siena.

Useful Resources on Pattern and Decoration

- With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985Our PickBy Anna Katz, Elissa Auther, Alex Kitnick, Rebecca Skafsgaard Lowery, et al.

- Collection Applied Design: A Kim MacConnel Retrospective (MUSEUM OF CONTE)By Robin Clark, Richard Marshall, and Kim MacConnel

- Robert Zakanitch's Big Bungelow SuiteThe Madonna of the Future: Essays in a Pluralistic World / By Arthur C. Danto / University of California Press

- R. Buckminster Fuller: Pattern-ThinkingBy R. Buckminster Fuller

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI