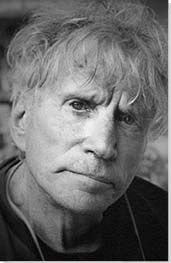

Summary of Dennis Oppenheim

Dennis Oppenheim's art career grew and changed from a legendary scarcity of objects and refusal of the gallery system; to oversize and overwhelming motorized installations; to a contemporary turn towards large-scale Surrealism, with his life size "architectural mirages". He was an integral figure in advancing the definition of art - as idea, intervention, fleeting moment, large monument - and expanding the realm of art outside the gallery. More than any other contemporary artist, Oppenheim was pivotal in contributing to the foundational and defining moments of multiple art movements, most notably Performance, Conceptual, and Earth Art. Throughout his career, Oppenheim jumped between movements, materials, styles, and themes; maddening critics who tried to define him. Oppenheim stated, "I've always wanted to operate within the entire arena. Signature style has been suspicious to me; it reads as a limitation."

Accomplishments

- Throughout his career, Oppenheim's work critiqued elitist art institutions. He once stated, "A museum is not a place I am dying to visit in any city. My interest in art is in an art that is yet to be made." This aversion to working inside the white cube of the gallery is an idea that has continued to influence significant artists working in Land art and Public Art including Alan Sonfist, Christo and Jean-Claude, and Maya Lin.

- Oppenheim was part of the early generation of Land artists, along with Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Nancy Holt, and Michael Heizer. They pioneered this new form of art in the 1960s, in which the earth itself served as medium. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Oppenheim's early interventions into natural landscape took the form of removal, returning to the ancient sculptural principal of carving, by, in the artist's own words, "taking away rather than adding".

- The process of removal was also important to Oppenheim's investment in the dematerialization and de-commodification of the art object. His ephemeral, time, and idea-based works, which resisted circulation in the art market of the 1960s and 1970s, were often produced by a literal, playful, and documented removal of the object, as in his Indentations series.

- All through a disparate and multimedia practice, the specific, corporeal, discrete bodies of both artist and the viewer were always integral to Oppenheim. He has used his body as art (via exposing his skin to the sun), made sculptural interventions in which the viewers' embodied actions activate the work (as in his viewing platforms, which an audience stands on and looks out from and not at), and made public artworks that intentionally disorient those that encounter them through playing with scale, orientation, and perception (as in his large scale architectural pieces).

- In 1979, Rosalind Krauss wrote 'Sculpture in the Expanded Field', a foundational essay describing how sculpture had shifted from being a monument, to an object on a plinth, to an intervention or installation in landscape or architecture. Oppenheim was a key figure in rethinking and expanding sculpture to be site-specific, in public, part of landscape, and part of architecture, throughout his career.

Important Art by Dennis Oppenheim

Dead Furrow

This work existed only in sketches, as a scale model, and as an indoor structure for viewing a gallery space in Belgium, until it was finally realized out-of-doors in physical form at the Storm King Art Center in 2016, where it was able to fulfill one of Oppenheim's original key requirements: that the work have a mile of clear space in every direction.

In 1967, Oppenheim proposed a series of Viewing Stations, that is, platforms intended for viewing the surrounding vistas. Thus, although the platforms were to be sculptural constructs, the primary content of the work was to be the natural landscape itself. As Oppenheim explained, these viewing stations were designed as "works to view from," rather than objects to look at, thus completely inverting the relationship between the art object and its function. Further, by positioning themselves on top of the platform, said viewer also becomes an object to be viewed by others, and their desire to look becomes central to the work's function, thereby emphasizing the embodied aspect of looking itself. The structure of the central platform was inspired by the shape of Mesoamerican temples (such as the structure in Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico, dating to about 500 B.C.). These ancient sites and the cultures that created them fascinated Oppenheim. At these sites, rituals of worship were intimately linked to performances of seeing and being seen that implicated human participants, deities, and the natural world.

The title of this work, Dead Furrow, refers to the trenches that are created after a field is plowed. The PVC pipes in this work aim to replicate these dead furrows. By using an industrial material to recreate a pattern usually created in the terrain, Oppenheim creates a transitional zone between the natural environment surrounding the platform, and the man-made structure of the central platform. In this way, he demonstrated an early understanding of the potential tensions that exist in any attempt to introduce an artistic intervention into a natural setting. This desire to "fit" his sculptural interventions conscientiously into the surrounding environment would go on to define much of his oeuvre throughout his life. It is also interesting to note that Oppenheim was considering these relationships right at the beginning of his career, before his more serious involvement with Earth Art. Oppenheim's widow, Amy Plumb Oppenheim, recently confirmed, "He had this in mind before he met with Robert Smithson and the Land artists. He had this in mind when he was still in Hawaii."

Wood surfaced with organic pigment and PVC pipe - Storm King Art Center

Indentation-Removal

In 1967 and 1968, Oppenheim was involved with a series he called Indentations. The artist would find an object lying in the dirt (often in vacant lots in New York City, Amsterdam, and Paris). He would photograph the object as he found it, before removing the object and taking a second photograph of the indentation its removal had left in the ground. As Art Critic Thomas McEvilley notes, "The indentation, that is, the absence rather than the presence of an object, was the artwork." While the artwork becomes a space to look from and not at in Dead Furrow, with Indentations the artwork becomes the space left behind after the object is gone.

At the time that Oppenheim was creating these Indentations, many other artists in Europe and North America were engaged in a similar rejection of Modernist aesthetics and its obsession with the object, by conceiving of art as a removal rather than an addition. For instance, for an exhibition at the Iris Clert Gallery in April 1958, French artist Yves Klein removed everything in the gallery space except a large cabinet, opting to show nothing at all. McEvilley explains, "Rather than adding yet another object to the already crowded world, the artist would begin to clear things away, in an analogy to clearing away illusions." At the same time, artists working in Minimalism were following the critic Clement Greenberg who had advocated for reducing the artwork to its essential elements, while artists working in Conceptualism were doing away with physical process and art objects altogether. These concurrent efforts to redirect focus away from the art object came to be known as the "dematerialization of art" (coined by art critic and curator, Lucy Lippard).

The ideas of dematerialization, removal, and the anti-object were central to another series of works by Oppenheim in 1968, titled Decompositions. In these works, Oppenheim created piles on the gallery floor of powdered versions of the materials from which the gallery walls were made, including sawdust and powdered gypsum. By invoking the idea of a physical demolition of the gallery, Oppenheim was also engaging in a critique of the art institution. McEvilley refers to the series as "an attack on [the gallery's] ideology of preciousness and separateness, dissolving its walls to let in the outside world".

Color photography, collage text on rag board - Haines Gallery, San Francisco

Annual Rings

This image provides documentation of a performance/earthwork that Oppenheim carried out along the U.S.-Canada border, on either side of St John's River. By plowing the snow that lay to the sides of the river, the artist recreated the rings created inside tree trunks due to annual growth.

This site-specific work aimed to reference and highlight various social and natural systems, including geo-political boundaries, time zones, and natural decay. The map is reproduced to highlight the role of mapping in producing artificial and often violent boundaries between states. Here, the river (a natural boundary) is instrumentalized in the service of these borders between nations (human made artificial boundaries). The St John's River acts not only as part of a national border, but also as a line dividing two time zones. Time itself was an important aspect of the intervention as demonstrated in the title and form of the rings (to delineate years) and in the melting of the snow, which made the work temporary; its duration bound to weather and temperature conditions, over which the artist had no control.

Through the juxtaposition of natural elements with man-made concepts like nationhood and time zones, Oppenheim called into question the "the relative values of the ordering systems by which we live." Around the same time, earth artists like Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria, who were also creating site-specific Earthworks where natural environments were put into tension with man-made interventions, were posing similar questions.

Gelatin silver print(s), ink on paper, photomechanical prints, wax crayon - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Reading Position for Second Degree Burn

Still engaged in "dematerialized" art, Oppenheim began to explore the ways that his own body could be used to carry out artistic concepts. He describes this work as a corporeal enactment of painting, explaining, "The piece incorporates an inversion or reversal of energy expenditure. The body is placed in the position of recipient ... an exposed plane, a captive surface. The piece has its roots in a notion of color change. Painters have always artificially instigated color activity. I allow myself to be painted ... my skin becomes pigment. I can regulate its intensity through control of the exposure time. Not only do the skin tones change, but change registers on a sensory level as well. I feel the act of becoming red." The language and process of 'exposure' with regard to intensity of color also links to photographic and development processes, including the processes, which would have produced these documentation images of the artist's 'exposed' chest.

Shortly before this work was carried out, Oppenheim befriended Performance artist Vito Acconci, who would go on to become famous for his subversive performances, which frequently focused on the artist's own body, such as Trademarks (1970), in which he bit down on various parts of his own body hard enough to break the skin, and Conversions (1971), in which he used matches to singe off his own chest hair. It is evident that the two friends were exploring similar ideas around this time, focusing on the ways that they could use their own bodies to enact art making, at times exploring the limits of pain that they could endure. As well, Oppenheim's body-focused performance art of the early 1970s bore strong similarities to that of Marina Abramovic. There is a strong affinity between Abramovic's Rhythm O (1974) and Oppenheim's Rocked Circle - Fear (1971), in which he stood in a circle with a diameter of five feet while viewers threw rocks at him. In works by all of these artists, the performances left physical marks and scars on their bodies, which endured past the end of the performance itself, but would ultimately fade away. Thus documentation through photography was an important secondary aspect of their performances.

Reading Position for Second Degree Burn is an important document of the experimental performance practices of the 1960s and 70s, and is singular in its tongue-in-cheek references to traditional art processes such as photography and painting, which have influenced a number of more playful performance practices, including those of Angus Fairhurst, Roman Ondák, and Janine Antoni.

Chromogenic print - Irish Museum of Modern Art

Formula Compound (A Combustion Chamber, An Exorcism)

This site-specific sculptural work sits in a broad field surrounded by thick forest. It is comprised of a tall central tower, joined by overhead cables to a structure further up the slope. The tower is also joined by curved "launching ramps" to a structure further down the slope. Below the main sculpture, a series of square panels (each providing different levels of transparency) allow visitors to view the work in different ways.

In the early 1980s, after working for several years primarily in the dematerialized terrain of land and body art, Oppenheim felt a desire to return to the art object. He recalls that this period "was more about the movement from very dematerialized work, which was body art, to something that had more physical structure [...] I guess you could say it was a return to structure after being involved with conceptual deconstruction [...] Armatures, steel, physicality, presence. Things above the ground." At this time, he began using industrial materials to create large sculptural works that resembled machines intended for launching fireworks. For the artist, these complex machines served as a metaphor for human thought processes, or what he referred to as "cerebral maps", with the firework projectiles acting as "thought lines".

In total, Oppenheim created five works in this Fireworks Series. Formula Compound (A Combustion Chamber, An Exorcism) is the only one of the five that was never actually used for igniting fireworks. It was designed for and built at the Gori Collection of Site-Specific Art in Tuscany. In fact, Oppenheim was one of the original ten artists (along with Alice Aycock, Ulrich Ruckriem, Robert Morris, Mauro Staccioli, Dani Karavan, Richard Serra, George Trakas, and Anne and Patrick Poirier), who collector Giuliano Gori invited to stay at his property for several months during 1980-1981 in order to begin populating the Villa and adjoining nineteenth-century English-style Romantic garden with site-specific works.

At the time of its construction, an enormous oak tree stood just next to, and towered over, the work's central tower. By dwarfing the sculpture in comparison, this oak lent the work a sense of humility in the face of nature. However, on April 20, 2005, a dramatic windstorm brought down the oak on top of part of the sculpture, destroying a section of the work. When consulted on this matter, Oppenheim insisted that the felled tree not be removed, and the work not repaired. This deference to the site on which his public sculpture was produced is very different to the attitudes of most artists working in the public sphere, particularly with large-scale sculptures, and again demonstrates the artist's dedication to process, liveness, and protecting the natural landscape.

Steel and iron - Gori Collection of Site-Specific Art at the Fattoria Celle, Santomato, Italy

Device to Root Out Evil

This sculpture is comprised of a New England-style church built upside-down, perched precariously upon the point of its steeple, which drives down toward the ground. This sculpture is characteristic of Oppenheim's later work, in which he sought to transform everyday objects, and to fuse sculpture and architecture. He later explained that the work was "very well-received as a sculpture, as both a concept of architectural sort of reorientation - you render this building unusable by turning it upside down, and it's not functional anymore; so it becomes sculpture."

Oppenheim said of the work; "It's a very simple gesture that's made here, simply turning something upside-down. One is always looking for a basic gesture in sculpture, economy of gesture: it is the simplest, most direct means to a work. Turning something upside-down elicits a reversal of content and pointing a steeple into the ground directs it to hell as opposed to heaven." This inversion - from architecture to sculpture, usefulness to uselessness, object to art - is a direct quotation of Marcel Duchamp's famous Fountain (1917) in which a urinal is placed upside down and titled and becomes an art object through this nomination as such. Despite a return to the art object in his later work, this monumental sculptural work is still imbued with his conceptualist roots, and also makes use of the dry humor prevalent throughout his career.

Originally titled Church, the project was proposed to New York City's Public Art Fund, with the intention of being located in Church Street, (the same street in which the artist was living at the time). However, the work was considered too controversial and was not approved. Oppenheim decided to change the name so as to be less controversial, and built the sculpture to be installed as part of the 1997 Venice Biennale. Since then, the work has been moved from one home to another, as various purchasers (including Stanford University in 2003, Vancouver's Harbour Green Park in 2005, and Glenbow Museum in Calgary in 2008) have taken in the work, only to painfully reconsider the decision shortly after due to the work's "inappropriate", "controversial", and "sacrilegious" nature. The work currently resides in the Plaza de la Puerta de Santa Catalina in Palma, Mallorca, since its relocation in 2014.

Red Venetian glass and steel - Plaza de la Puerta de Santa Catalina, Palma, Mallorca

Biography of Dennis Oppenheim

Childhood

Dennis Oppenheim was born in Mason City, Washington (later renamed Electric City) which he explained "was really primarily a construction site for the construction of [the Grand Coulee] dam [and] it certainly is not a city. It's not even a town. It's kind of a ghost town without a town. It does not exist." The family lived there while his father worked as an engineer on the dam, but soon after Dennis' birth they returned to their home in Richmond, El Torito, near Berkeley, in the San Francisco Bay area. Richmond was primarily a shipyard-building town during the war, and one of its main employers post-war was Standard Oil.

Both of Oppenheim's parents were Russian immigrants. His father was Jewish, born in China, and educated at the University of Hong Kong and later at the University of California at Berkeley where he received a Master's degree in engineering. He noted that his father stood out as markedly different from the local working-class El Torito community, both because of his strong Russian accent and his status as a professional. Oppenheim's mother studied English at the University of California. He described her as a "sensitive creative individual" who was very much involved in the arts: playing piano, working with marionettes, and writing poetry. He noted that his parents were "both relatively non-conformist. Oppenheim had one sister, a year older than himself, with whom he had a "rather cool" and "relatively neutral" relationship.

Oppenheim attended Richmond High school, which he described as "enormously overcrowded," as it was built for about one thousand students but in fact served about five thousand. He recalled, "I think one of the positive things that grew out of this experience in Richmond was a real close alignment with the minority class, which I did in a natural way. Particularly the African Americans [...] I was popular with them." Oppenheim was quite involved with sports during high school, participating in track and field and swimming, although he said that he "never played football. Something about football, it was just too American. I had trouble with that."

As for the arts, Oppenheim explained that "I was kind of showing signs of artistic ability early in grammar school, punctuating this population of mediocrity and of relatively low-spirited imagination. I was operating with great resistance. Because being an artist was not a popular thing at all. It was ridiculed because at that time it would appear to be more of an alignment to a feminine activity [...] I used to put on marionette shows and things [in elementary school], that really excited a lot of resistance from my pals who were all hard core juvenile delinquents." He then stated that he became more of a conformist in high school, as he wanted to "be identified as being one of the guys" and he thus resisted his sensitive side, keeping any involvement in art "rather secret and somewhat hidden. Not announced with any great claim, although I did know that I related to it." Nevertheless, he did take some art classes in his later years at the high school. Another student who attended high school with Oppenheim was artist, sculptor, illustrator, and composer Walter De Maria. Oppenheim was friends with De Maria's younger brother, and describes the adolescent artist as "mysterious".

Education and Early Training

Oppenheim stated, "I didn't leave high school knowing that I was going to become an artist, although it was really something I considered. I was not sure. I experienced a short period of questioning at that time." He spent a year working at his first-ever job (at a shipyard) and feeling "uncomfortable" and "really quite lost", before enrolling in the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1958. He describes this college as "the obvious choice", as it allowed him to continue living at home. Moreover, many of his friends went to UC Berkeley, but students were required to have an additional language in order to attend, which Oppenheim did not.

He described his early college experience as "an awakening, because here one was all of a sudden thrown in with all of these people that you identified with, and never knew exactly how strong your identity would be until you saw them all together." It was also here that he met his future wife, Karen Cackett. During his first year of college, he kept up his shipyard job, which he recalls as being "not an enjoyable job at all," to help finance his education and have some extra spending money. Every day he awoke at 6:30am, packed two meals (lunch and dinner) and then drove to his 7:30am Art History class. He left school at 3:00pm and drove thirty miles to the shipyard to start work at 4:00pm until midnight. After a year of this grueling schedule, he was laid off and went on unemployment benefits. During that busy first year, he was unable to concentrate fully on his studies, but as of his second year he began to perform very well in school. He recalls two of his sculpting teachers who were the first New Yorkers he had ever met, as being "very important" to him, "sharp," "tough," "verbal," and "stimulating" teachers (despite not being very good artists). The students worked in plaster and Styrofoam as well as a bit of welding. Oppenheim also worked a lot in watercolor at that time.

However, he dropped out of college before completing his degree, got married to Cackett, and moved to Honolulu along with the rest of his family. His father had been relocated there, and had suggested to his son "This is probably a chance for you to do something, and you may as well travel." Oppenheim taught briefly at the University of Hawaii before starting his own Public Relations business. He explained, "all of a sudden I became this kind of extraordinary young versatile entrepreneur." What's more, he was experiencing financial success, and by 1960 he was able to purchase a large house for his wife and first, and later second child (Erik and Kristin respectively) and a fancy car. He said that by 1962 "I made a lot of money. I had all kinds of things. But I was developing a rather poor marriage, and so my wife went back home for a little rest, as we called it. And at that point everything fell apart. Not that that was such a trauma for me, it was just that things were beginning to unfold into what was going to be this continual state of highs and lows which was going to, unbeknownst to me, occur forever."

The couple soon got divorced; Oppenheim closed his PR firm, and went back to school, this time at the University of Hawaii, full-time. As he recalled, "All of a sudden I was back, after a hiatus of two years, in a school environment, and I was about almost twenty-three years old [...] the University of Hawaii in 1960 was quite something. I mean, it was a tropical environment and it captivated a lot of people from various parts of America, many of them interesting. I think I was older with my ability to differentiate between the substance of one person and the value of another was much more acute." During this period he developed strong relationships with several new friends, and "a general feeling of spiritual camaraderie with this group that made up the creative department in the arts".

The teacher that had the greatest impact on him at this time was Burt Carpenter, who went on to become curator/director of Witherspoon Art Gallery in North Carolina. Carpenter taught Oppenheim both in studio classes and art history, and took an instant liking to him. Oppenheim used this time to experiment with various ideas. He stated, "I used to dig holes in the ground, and I'd throw in a lot of broke and rusty steel and pieces that were kind of randomly placed, but yet want to address a certain physiological body component. And then I'd throw plaster in. I'd make these dirt paths and then I'd throw them out, and then I'd burn them, and I purely was identifying, at that time, with remnants of the abstract expressionist sensibility." He also experimented with paintings that were "abstract figurations". However, once again he left before completing his degree, this time to return to the California College of Arts and Crafts.

He remembered this step as "kind of a defeat, in a way, because [...] I was going back to the school I was at when I was a kid. I was older. And for some reason, I ended up in the dormitory. I didn't stay there long. I knew that that was impossible. I was pretty unstable." At this time he struggled with depression, often visiting doctors and taking medications to "equalize" himself. He later noted, "As a survivor of these things, one can develop certain strengths that are useful in making art. They can be in the form of allowing yourself close proximity to dangerous psychological states. For instance, because you tested things, you're more capable of knowing when you're on the brink. You're more capable of examining things, turning them over, looking at them in different ways that are really very difficult, very hard, that have a kind of sinister aspect to them. You can look at very dark things. You aren't afraid. Your level of fear has been compromised because you've experienced things. So this is all ammunition that you can use in art making."

He finally graduated with a degree in Education and a minor in English in 1964, and then promptly received a scholarship to do his Masters of Fine Arts at Stanford, which he completed in a mere nine months. His education at Stanford was comprised nearly entirely of studio work. He said, "I remember distinctly that the day I arrived at Stanford and the day I left, I didn't miss one day in the studio. I mean, I worked every day for nine months, and sometimes all night. So I worked all the time. I expanded from one room to about six rooms. I took over an entire building, work that would overflow in the courtyard. I did hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pieces. I was reading a lot, I was developing theory". He also noted, "I developed extraordinarily lofty intellectual positions because I was being persuaded by a real natural urge for radical upset. I was really sure at that point, without doubt, that I wanted to be a cutting edge artist."

Mature Period

Oppenheim moved to New York in 1966, and in 1967, he moved into the Tribeca loft that served as his home and studio until his death in 2011. (For the last three decades of his life, he also owned a second home in The Springs on Long Island, next door to Jackson Pollock's house, where he liked to simply "go and think".) He taught art at a nursery school in Northport, as well as at a junior high school in Smithtown, Long Island, all the while working toward his first one-person New York show, which was held at the John Gibson Gallery in 1968. The show included mainly photographs and maps of his outdoor Land art works, including Annual Rings. His third child, Chanda, was born to Phyllis Jalbert that same year.

Oppenheim received a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 1969, and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in 1974 and 1982. By the early 1970s he had joined the Art Workers' Coalition, along with Minimalist sculptors Carl Andre and Robert Morris. The group organized demonstrations at the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the aim of implementing economic and political reforms. In the early 1980s he presented workshops at the Visual Arts Center of Alaska.

In 1981 he married the sculptor Alice Aycock while the two were working together with eight other artists (including Ulrich Ruckriem, Robert Morris, Mauro Staccioli, Dani Karavan, Richard Serra, George Trakas, and Anne and Patrick Poirier) on the first group of works that would begin the Gori Collection of Site-Specific Art at the Fattoria Celle, in Santomato, Tuscany (part-way between Florence and Pisa). Oppenheim and Aycock were both constructing large-scale metal sculptures next to each other in the English-style Romantic gardens on the property. The marriage was short-lived, but the two remained close friends.

During the early 1970s, Oppenheim turned to Performance art, focusing on the use of his own body. But in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he returned to the material art object, creating large sculptures from industrial materials. Around 1986, Oppenheim entered a period where he stopped working for about three or four years. He later explained, "I just wanted to sort of feel stuff out."

Although he quit drinking in the 1990s, Oppenheim's house hosted some of the wildest parties of his time, with artists like Vito Acconci, Robert Smithson, and Chris Burden in attendance.

Author and friend, Charlie Finch wrote in his obituary, "Hugh Hefner was a street urchin compared to Dennis when it came to hosting parties", going on to describe the lavish events at which party crashers were always welcome.

Late Period

In the later years of his career, Oppenheim focused on creating permanent outdoor sculptures that engaged with the surrounding environment in metaphorical ways. At this time, he felt a need to focus on public works in an attempt to "find an alternative to museums and galleries" - although he admitted, "public art has always been a bittersweet and disappointing context over the last 20 years. It really has produced some of the worst sculpture in the world [...] It's a receptacle for bad art. What it offers an artist is an excruciating interaction with bureaucrats and overseers who invariably make a good work impossible. It aligns the artists with architects, who are often resistant, and puts the artist into a no-win position of impossible problems. One must develop a new kind of thinking process in order to interface with the power structure of public art successfully."

In 1998, he married Amy Van Winkle Plumb, and they remained together until his passing from liver cancer in 2011 at the age of 72.

The Legacy of Dennis Oppenheim

Oppenheim was one of the first to advocate strongly for the use of photography in ephemeral Land and Performance works, stating that the photograph was "necessary as a residue of communication".

Oppenheim's early earthworks, such as Annual Rings (1968), which involved modifications to natural substances (such as snow and earth) that would eventually yield to the forces of nature and disappear completely, directly influenced his Land artist contemporaries, such as his close friend, Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty (1970), as well as in more recent work by Richard Long. His influence can also be seen in the works of later artists, such as Andy Goldsworthy, who used the earth and natural elements, as well as his own body, in his "ephemeral" artworks.

Oppenheim was also a pioneer of performance art that focused on the limits of the artist's own body in the 1970s, along with artists like Valie Export, Vito Acconci, and Marina Abramovic. Oppenheim was particularly close with Acconci, saying that they "began about the same time, and we were always quite friendly, and basically we've supported each other [...] I have always liked his work [...] He is quite a different kind of artist. But yet we shared some of the same risk-taking and some of the same inability to do the same thing over and over again. Our position in the market is relatively relaxed. So we have characteristics that we share."

British sculptor Stephen Cripps cited Oppenheim's mechanical sculptures of the 1970s and his firework-launching machines of the early 1980s as having strongly influenced his own "Pyrotechnic" Sculptures of the same period.

His daughter, Kristin Oppenheim is a respected artist working in New York and working predominately in sound and light installations.

Influences and Connections

-

![Vito Acconci]() Vito Acconci

Vito Acconci -

![Carl Andre]() Carl Andre

Carl Andre -

![Robert Morris]() Robert Morris

Robert Morris - Alice Aycock

-

![Richard Long]() Richard Long

Richard Long -

![Maya Lin]() Maya Lin

Maya Lin - Beverly Pepper

-

![Vito Acconci]() Vito Acconci

Vito Acconci -

![Carl Andre]() Carl Andre

Carl Andre -

![Robert Morris]() Robert Morris

Robert Morris - Alice Aycock

Useful Resources on Dennis Oppenheim

- Dennis Oppenheim: Body to Performance 1969-73Our PickBy Nick Kaye and Amy Van Winkle Oppenheim

- Dennis Oppenheim: Selected Works 1967-90By Alanna Heiss

- Dennis Oppenheim: Public ProjectsBy Aaron Levy, Vito Acconci, and Aaron Betsky

- Dennis OppenheimOur PickBy Lóránd Hegyi and Alberto Fiz

- Dennis Oppenheim: ExplorationsBy Germano Celant, Lynn Hershman, Nick Kaye, Willoughby Sharp, Steve Wood, Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, Assumpta Bassas, and Oliver Zahm