Summary of Mike Kelley

Mike Kelley took a scalpel to late-20th-century American popular culture, estranging the familiar and exposing society's dark underbelly in works that were as wide-ranging in their subject matter as they were inventive in choice and combination of media. From the beginning, Kelley's anarchic performances and videos resonated with the emergent DIY ethos of the late 1970s and early 1980s punk subculture, first in his native Michigan, and then in Los Angeles. From there, his heterogeneous practice struck a chord with the climate of postmodern theory during the 1980s and 1990s. Kelley's musical activities and his collaborative work with acts such as Sonic Youth were also a key link between the art and rock worlds during those decades. And as his work became more and more complex and ambitious, Kelley did much to open up the potential of Installation art to absorb new media, and to captivate and overwhelm the viewer in immersive and often chaotic ensembles of disparate objects. Upon his suicide in 2012 at the age of 57, Kelley bequeathed to a younger generation of film, video, performance, and installation artists, a legacy of visual and sonic assaults upon the viewer's moral certainties, aesthetic sensibilities, and the decorum of the gallery environment.

Accomplishments

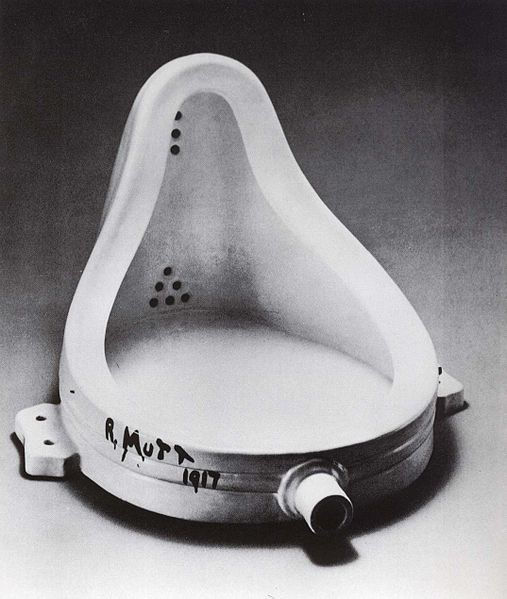

- Kelley incorporated found objects - most famously, soft toys - into many of his works. Often sourced from thrift stores, these objects added a distinctive chapter to the history of the readymade in contemporary art, whose origins lie in the practices of Dadaists such as Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters. Signifying failure, waste, and regret as well as connoting symbolic and actual violence, Kelley's use of the found object became a key component of the trend towards abject themes in contemporary art of the late 1980s and 1990s.

- Gathering diverse found materials from a wide variety of sources, Kelley acted as a pop ethnographer of kitsch Americana, low-brow culture and the rituals and rites of passage of everyday suburban and small-town life. Incorporating all of these themes into his work, Kelley helped to forge the notion, now widespread, of the contemporary artist as akin to an amateur cultural anthropologist.

- With careful planning and editing, Kelley often assembled works of different media into installations of various constituent parts. In doing so, he helped to debunk the traditional expectation that the artist must be a 'master' of a particular medium. Instead, the unifying factor in many of Kelley's heterogeneous installations and sculptural assemblages became above all conceptual rather than formal.

- Kelley was a prolific collaborator, and as both a teacher and an artist, he fostered an ethos of generosity and creative exchange that would exert an influence upon a younger generation of 'relational' artists that emerged in the 1990s.

Important Art by Mike Kelley

The Banana Man

Kelley's first solo video work, The Banana Man, depicts the artist performing in the guise of the eponymous "Banana Man", a minor character from the popular children's television show Captain Kangaroo. While the show was familiar to Kelley from his youth, he had never himself witnessed the Banana Man on screen. Instead, what he described as his "attempt to construct a psychology of the Banana Man" relied entirely on his memories of childhood friends' descriptions of the character. The resulting "series of scenes" is based on two fragments of childhood "hearsay": that the Banana Man liked to pull long items from his many pockets, including toy trains and strings of hot dogs, and that his only vocalisation was an "oooh" sound that accompanied this repetitive activity. In The Banana Man, Kelley explores the possibilities for suggesting individual character by way of the slightest of cues.

Kelley had created performances while still a graduate student at CalArts, often working in collaboration with fellow students including Tony Oursler and Jim Shaw. Of Kelley's early performances, Oursler has recalled that "you couldn't see him perform without feeling invigorated and confused. You realized you were caught up in a tide-pool of Freudian and Jungian misnomers with a punk overtone to it all - he was chaos and utter brilliance." However, Kelley resisted capturing these early performances on video, since he felt uncomfortable recording events that were intended to be witnessed first-hand.

By contrast, just a few years after his graduation from CalArts, this video recording of The Banana Man deliberately exploits the potential of multimedia editing to sustain the illusion of character. As Kelley explains: "Because of the conventions of editing, video and film tend to normalize fracture. The viewer is expected to jump from one image to the next and experience it as a seamless development. To me, this experience of seamlessness seemed to correspond to the notion of unified character."

Kelley's lack of familiarity with the original Banana Man, and his reliance on distant memories, ensures that, despite a full twenty-eight minutes of edited performance, the figure finally remains little more than an absurd cipher. But this incompletion is also an offering to the viewer to fill in the gaps and to project their own sense of this half-forgotten oddball. For Kelley, "it is up to the viewer to come to terms with what this character is". As such, the open-ended nature of The Banana Man seems to resonate with postmodern notions of its time that are still relevant today, suggesting individual subjectivity as an unfixed tissue of fragments heavily determined by the media and other social structures.

28 min color film - Electronic Arts Intermix, New York City

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid marks the first time that Kelley used stuffed-animal toys as a medium. These objects would go on to become a hallmark of the artist's mature practice, and More Love Hours itself is a significant moment in the emergence of the degraded "junk" aesthetic cultivated in the work of many artists in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, from Jason Rhoades to Rirkrit Tiravanija and Thomas Hirschhorn - the "chaotic arrangement" of the "flea market" that the influential curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud would, in 2002, identify as "the dominant art form of the nineties".

Kelley collected these discarded tokens of childhood devotion from thrift stores, tightly arranging them among assorted crocheted afghans on a large canvas measuring eight by ten feet. Apparently tacked to the wall by two ears of dried corn at the upper right- and left-hand corners, this dense assemblage of soiled objects foreshadows the similarly crowded compositions of trinkets and tchotchkes of the later Memory Ware series of collages and sculptures that would eventually occupy Kelley in the last decade of his life.

The scale of More Love Hours recalls the heroic, hyper-masculine paintings of the Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s and 1950s, while the richly colored, all-over design of the work is reminiscent of Hans Hoffmann's "push-and-pull" paintings of the late 1950s, in a nod to Kelley's undergraduate training as a painter at the University of Michigan. By creating a quasi-abstract image from an accumulation of soft toys and blankets, Kelley pits low culture against high art, and mounts a sly assault on the high-minded aesthetics of 20th-century abstract painting. As art historian Howard Singerman explains, "high art is often a target in Kelley's work; he mistrusts particularly abstraction's claim to (at once) universal speech and pregnant silence... he refuses to acknowledge the line between high and low art."

More Love Hours's deflation of the ideals of high modernism is of a piece with its more general aura of emotional and spiritual disillusionment. The work's title also suggests wasted effort as a theme, whether this be the futile emotional labour of unrequited love, or the many long hours of stitching that were once required to create the toys and blankets themselves. More Love Hours was first exhibited at the Rosamund Felsen Gallery in Los Angeles with a companion sculpture, The Wages of Sin, an assembled shrine of homemade candles set atop a table and placed to the left of the wall hanging. Together with the (autobiographical) Catholic overtones of its companion piece, Kelley's work connotes themes of devotion, guilt, longing and debt that are left unspecified, but which nevertheless seem tinged with nostalgia for the lost innocence of childhood, while pointing with a bitter humor to the failures and disenchantments of adulthood.

Stuffed fabric toys and afghans on canvas - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

Pay For Your Pleasure

Pay for Your Pleasure has become one of Kelley's most celebrated works. The installation consists of a long corridor flanked on both sides by 42 large, colorful poster-like paintings depicting celebrated male poets, philosophers, and artists, with a quotation attributed to each individual above their portrait. Painted by commerical artists from photographs, the panels are reminiscent of the inspirational posters hanging in high school English classrooms across America. However, in Kelley's work, each quotation champions artistic genius as inherently rebellious and above the law. Oscar Wilde, for instance, is accompanied by his bold, art-for-art's-sake assertion that "the fact of a man being a poisoner is nothing against his prose."

Kelley's installation is now permanently housed at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. In its early days, however, it toured to different venues, the corridor ending at each iteration with the inclusion of an artwork created by a notorious local criminal. For the work's Chicago debut, viewers were thus greeted with a disturbing self-portrait by the Cook County serial killer John Wayne Gacy, dressed as his alter-ego, Pogo the Clown. Kelley finally placed donation boxes at the beginning and end of his corridor installation, allowing visitors to donate money to local charitable organizations assisting the victims of violent crimes. As the art critic Christopher Knight explains, "you're bluntly reminded to pay for your voyeuristic pleasure, as you sidle up to peruse the killer's aesthetic product. Like old-fashioned religious indulgences, the contribution boxes let you relieve your gnawing cultural guilt."

Pay for your Pleasure is mockingly site-specific, and like much of Kelley's work, it trains its sights on the viewer's discomfort, seeking to expose the contradictions and hypocrisies that lie at the heart of society and its conventions, including our expectations of art itself. Here, as Knight further explains, "Kelley's provocative installation gaily throws a monkey wrench into all sorts of entrenched assumptions about art. One is the romantic faith in art's value as a universal gauge of personal authenticity and worth. Another is the blandly sentimental assumption that art's highest purpose is to be redemptive."

Oil on Tyvek, wood, an artwork made by a violent criminal in (location of exhibition), and two donation boxes - Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood

Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood depicts a naked man and woman squatting over stuffed animals in sexual positions, creating what Kelley called a "fake pornographic" image. At the lower center of the photograph, the man uses what appears to be a toy rabbit to rub a dark substance against his buttocks. As art historian and critic Steve Baker explains, "the absence of color (in the photograph) increases the ambiguity of what is seen: the stuff smeared on the man's body might be read as blood, feces, oil, paint, or something else entirely." This ambiguity adds to the disturbing effect of the work as a whole, which marries its invocation of childhood purity with a depiction of adults displaying degraded, seemingly primitive and animalistic, behavior. For Kelley, it seems, the "innocence" of the title is a lie: "the stuffed animal is a pseudo-child, a cutified sexless being which represents the adult's perfect model of a child - a neutered pet."

The base subject matter of Nostalgic Depiction connects the work to themes of abjection that were developed by a host of artists working in the 1980s and 1990s, including Kiki Smith, Robert Gober and Cindy Sherman, each of whom explored transgressions of bodily propriety of one sort or another. The French theorist Julia Kristeva discusses abjection in her seminal book, Powers of Horror (1980), as that which "disturbs identity, system, order", and that "simultaneously beseeches and pulverizes the subject". For Kristeva, the abject exists at the limit point of the subject as that which the body expels or casts off: bodily fluids, for instance. Neither fully self nor other, the abject undoes the fiction of individual subjective integrity. In Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood, the abject, sexually aggressive activity of the two figures seems to point further still, towards the subversion of high art's traditional effacement of base, bodily pleasures. In Kelley's hands, abjection becomes a weapon in an act of aesthetic disobedience.

Sepia toned print, edition of 10 - The Art Institute of Chicago

Ahh...Youth!

Ahh...Youth! is a group of eight Cibachrome prints of mug-shot photographs, seven showing stuffed and knitted animals, and the eighth a youthful, harshly lit image of Kelley himself, taken from a high school yearbook. The seemingly innocent children's toys are framed in such a way as to impart a sense of deviousness to each, while Kelley - well turned out with a buttoned collar and his long hair brushed neatly backwards - appears at once impish and awkward.

The inclusion of his own image amongst soiled toys is, in part, an act of "self-caricature," as the artist, critic, and friend of Kelley's, John Miller, has suggested. At the same time, Kelley stares menacingly outwards as if to provoke the viewer. The resonance of "youth" in the work's title is, as in many of Kelley's works, left up to his audience to fathom. As Miller has explained, "(Kelley) considered art to be primarily a belief system in which viewers will make of artwork what they will." But here, with the clash between infant playthings and the disaffected and awkward adolescent laid bare, "youth" becomes somehow euphemistic, conjuring everything from boyish tomfoolery to unchannelled aggression and teenage sexual awakening.

In 1992, the experimental rock band, Sonic Youth, used one of Kelley's thrift-store soft-toy portraits from Ahh...Youth! for the cover of their album, Dirty. This helped to establish the work's place in the canon of Kelley's best-known creations, while the album's title nudged the possibly sinister subtext of the work a little further into the light.

8 Silver Dye-Bleach Photographs - Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts

Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites

Kelley steadily gained in notoriety stateside during the 1990s, the decade during which Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites came to epitomize his stuffed animal work for the American art world. Consisting of discarded stuffed animals sewn together face down into large, color-coordinated clusters, they hang from the ceiling in an almost planetary alignment. The once dirty and worn toys have been cleaned up, purifying them of their former lives as children's toys and allowing them to be viewed as serious components of his sculptures. As he declared of this work, "I wanted to say, no, this thing isn't of the past, this thing's here right now. It's not some metaphor for childhood; this is something that an adult made." To emphasize his point further, Kelley rounded off his installation with factory-made polygonal wall units to be hung from the surrounding gallery walls. In fact, these units function as oversized air fresheners, pumping their scent into the room at regular intervals in a tongue-in-cheek nod towards the sanitization of the soft-toy ensemble itself.

Interestingly, Deodorized Central Masses was first shown in Europe, where it received critical acclaim for its humorous reflection on American culture. For a European audience, the work's message was unambiguous: Kelley's stuffed animal spheres symbolized the profligacy of American consumer capitalism, and satirized a culture premised, from the earliest stirrings of childhood, on excess.

Plush toys sewn over wood and wire frames with Styrofoam packing material, nylon rope, pulleys, steel hardware and hanging plates, fiberglass, car paint, and disinfectant - Plush toys sewn over wood and wire frames with Styrofoam packing material, nylon rope, pulleys, steel hardware and hanging plates, fiberglass, car paint, and disinfectant

Educational Complex

Kelley's use of soiled stuffed toys, as well as the darkly sexual undertones to much of his work, eventually led to rumors and assumptions that he had been abused as a child. Rather than deny this, the artist decided to embrace his new biography: "Everybody thought it was about child abuse ... my abuse," he observed. "[So] I have to go with that ... make all of my work about my abuse. And not only that, but about everybody's abuse. This is our presumption ... that all motivation is based on some repressed trauma." Educational Complex was created as a result of Kelley's embrace of this pseudo-biography as well as his interest in Repressed Memory Syndrome, a form of amnesia that results from a traumatic or stressful event. The work is a sterile architectural model of all the educational institutions Kelley had ever been taught in, including his home, and even the basement of the CalArts building on the model's underside. Omitting any details of spaces that he was unable to recall, Kelley's work thereby implies, or at least leaves open the possibility, that childhood trauma might have taken place there.

While he encouraged viewers to assume that the work was about his own child abuse, at a more general level the work concerns the repression of memory as a result of the educational system's oppressive structure. As Kelley once observed, "my education must have been a form of mental abuse, of brainwashing." Curator and director of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, Philippe Vergne, explains further that "(the work is) about architecture and how power structures ... and education have an impact on youth. So youth for him isn't juvenile culture. It's actually a very profound understanding of what it means to grow up."

Painted foam core, fiberglass, plywood and wood - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

Day is Done

Before his death, Kelley intended to create an extensive video series consisting of 365 parts representing the days in a year. He called the project Extracurricular Activities Projective Reconstruction. In a series ultimately composed of 37 parts, Day is Done is a compilation of parts 2 through 32, totalling 32 video chapters. In the work, actors dressed as American stereotypes and supernatural beings perform examples of extracurricular activities sourced from found high school yearbooks that the artist had organized into files, with all the absurdity befitting adolescent rituals. Kelley selected activities that he described as "socially accepted rituals of deviance," including prom, hazing, and high school plays, staging histrionic video narratives around these events with adults portraying the teenagers. As Kelley explains, "For this project, I limited myself to specific iconographic motifs taken from the following files: Religious Performances, Thugs, Dance, Hick and Hillbilly, Halloween and Goth, Satanic, Mimes, and Equestrian Events. Many of the source photographs are of people in costume singing or dancing, so the resulting tapes are generally music videos. In fact, I consider Day Is Done to be a kind of fractured feature-length musical... The experience of viewing it is somewhat akin to channel-surfing on television."

The 169-minute work was originally seen within an ambitious installation comprising 25 individually designed viewing stations, each decked with photographs, props and drawings referencing scenes from particular chapters. Upon viewing the work at Gagosian Gallery in 2005, Jerry Saltz described Day is Done's "cluster-fuck aesthetic," arguing that "[Kelley] is the originator of his own form of sculptural mayhem: cacophonous disorienting agglomerations and sprawling installations of stuff heaped upon other stuff ... deeply carnivalesque, always operatic, and utterly unrelenting."

Kelley's integration of videos within complex, chaotic gallery environments has been influential upon a host of younger artists, including Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, and Laure Prouvost. This strategy can be understood as an update of the 19th-century German opera composer Richard Wagner's idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk or "total work of art". In his essay, Art and Revolution (1849), Wagner explains this as "an ideal work of art in which drama, music and other performing arts are integrated and each is subservient to the whole." Day is Done is Kelley's attempt to create a theatrical work of art that makes use of all art forms. In doing so, Kelley himself exceeds his role as visual artist to become producer, director, set designer, editor, choreographer and songwriter.

Color video, assembled props, sculptures, drawings, paintings, photographs, and various found objects - Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts

Mobile Homestead

Mobile Homestead is the last work Kelley created before his death and was completed posthumously. After his offer to purchase his original childhood home was declined, Kelley constructed a full-scale replica of the non-descript ranch house that he grew up in in the suburbs of Detroit. The permanent home of Kelley's replica house is outside the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit, but part of the ranch detaches and can be placed on a truck to be sent around the city for various community outreach events. The art historian Randy Kennedy explains that "in its humanitarian aims the work blurs the lines separating sculpture, performance, activism and community organizing and fits uneasily into the gallery and museum world."

When anchored at its permanent site, however, the Mobile Homestead connects to an underground complex - a windowless basement that is restricted to artists alone. In marked opposition to the project's altruistic façade, this space is "reserved for secret rites of an antisocial nature." Reachable only through hatches in the floor and via a subterranean tunnel system, the basement remains inaccessible to the casual visitor, despite its location outside a notionally "public" museum. As Kelley explains, the work as a whole represents "how one always has to hide one's true desires and beliefs behind a façade of socially acceptable lies." Mobile Homestead is Kelley's only public artwork because he disliked public art, once remarking that the work will be "a pleasure that is forced upon a public that, in most cases, finds no pleasure in it."

Full-scale replica of single-story ranch-style house - Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit

Biography of Mike Kelley

Childhood and Education

Born in a suburb of Detroit, Michigan in 1954, Mike Kelley grew up in a working class family as the youngest of four children. Ten years separated Kelley from his older siblings and, as a result, he spent much of his childhood alone, reading in his room. His father, a maintenance worker for the public school system, was not very involved in his children's lives. By contrast, his mother, a cook at Ford Motor Company's cafeteria, was, in Kelley's words, "a complete control freak." Growing up, he had a tumultuous relationship with his parents. In high school, he once wore a thrift-store dress to school just to upset them. His parents were devout Catholics, but by the time Kelley was in first grade, he remembers thinking that religion "was a load of shit."

It was during Kelley's adolescent years that art-making became a serious career option for him. He decided to become an artist in part because "at that time, it was the most despicable thing you could be in American culture. To be an artist at that time had absolutely no value. It was like planned failure." Kelley's parents did not approve of him pursuing such a career, but being the stubborn teenager that he was, he defied them. His father disowned him as a result. While in junior high, Kelley's art teacher, a closeted gay man who taught crafts, would become a surrogate father, supporting him in his interest in art and later inspiring him to incorporate low-brow culture into his work.

Kelley grew up during a time in which Michigan's cities were facing severe crises caused by rapid deindustrialization, the civil rights movement, and economic downturn. This environment fostered a degree of cynicism in the young Kelley, eventually leading him to embrace the anarchist counterculture. Kelley became an avid participant in both the politically far-left White Panther Party and the underground punk music scene. In 1973, while attending the University of Michigan, he co-founded an improv noise band called Destroy All Monsters. Kelley and fellow artist Jim Shaw quit the band three years later to attend graduate school in California.

Early Training

Enrolling at the California Institute of Arts (CalArts) in 1976, Kelley encountered two teachers who would strongly influence his practice: the conceptual artist John Baldessari and the performance artist and musician Laurie Anderson. Fully embracing the ideals of the avant-garde, Kelley explored as wide a variety of media as possible, including performance, video, writing, and traditional crafts. He also began a second experimental band, The Poetics, with his roommates and fellow installation artists Tony Oursler and John Miller. At CalArts, Kelley was especially drawn to performance art and craft media because each, in different ways, posed a challenge to the category, and accepted practices, of fine art. Graduating in 1978, he opted to remain on the west coast, shunning the lure of the New York art world.

Mature and Late Period

After his time at CalArts, Kelley first found success in Europe, with shows in Germany and France garnering particular attention. But while his reputation grew steadily during the 1980s, Kelley's art-world stardom only fully arrived in the subsequent decade. 1992, in particular, proved to be a watershed year, marking the beginning of Kelley's career on the graduate teaching faculty at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where he would remain a professor until 2007. He acquired a reputation here as a supportive but tough teacher, whose critiques were always brutally honest. In addition, 1992 saw Kelley participate in the landmark group exhibition, Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s, at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, along with fellow California artists and collaborators Jim Shaw, Raymond Pettibon, Paul McCarthy, and Chris Burden. The show consisted of artists whose works shared "a common vision in which alienation, dispossession, perversity, sex, and violence either dominate the landscape or form disruptive undercurrents," as the show's press release proclaimed. Considered among the more important group exhibitions of the early 1990s, Helter Skelter gained a great deal of attention, and finally secured Kelley's reputation in the United States.

In addition to his teaching and artistic practice, Kelley remained a prolific writer throughout his career, penning articles and essays on a wide range of subjects from art, film, and architecture to subcultural topics as various as Ufology and Mexican wrestling. As in his art, Kelley himself was a man of contradictions. As the art journalist Kelly Crow reveals, "He hated to drive or fly - his agoraphobia and anxiety growing worse over the course of his life. His artworks earned him a fortune, yet he shopped mainly at secondhand stores and wore a pair of his father's red loafers for years. He painted just about every bedroom he ever had a particular shade of cucumber green."

In 2012, at the age of 57, Kelley committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, just as plans for his first major international retrospective were taking shape. He was found in the bathtub with a Smith & Wesson revolver, Xanax, vodka, soda, and a barbecue grill that he had lit after covering the room's vents with duct tape. Taped to the wall beside him was a photo of his ex-girlfriend, Trulee Grace Hall, a young design student whom Kelley had met several years after he stopped teaching. Their relationship had ended a few months prior to his death, and Kelley had also been struggling with numerous personal issues including depression, alcoholism, and the recent passing of his mother and brother. His self-inflicted death shocked the art world, but there were signs. Just before his death, he had confided to a few close friends that he was struggling to keep his faith in art and had threatened to stop making it. In his final interview, for Artillery Magazine, the critic Tulsa Kinney wrote that "...we sat in a darkened living room, and he left the curtains drawn. As we spoke, he blankly stared straight ahead, replying to my questions in a deliberate monotone."

The Legacy of Mike Kelley

Kelley eventually became the leading figure in the Los Angeles art scene, and his championing of Los Angeles led to its international ascendancy as an art capital, paving the way for a generation of future artists to make the city their home, including those - like painter Mark Grotjahn and sculptor Sterling Ruby - who had moved to Los Angeles specifically to study with the artist.

Kelley has had a significant impact upon the subsequent course of contemporary American and European art. The art historian Thomas Crow explains that "he was a figure who was a bridge from the breakout 1960s generation of Minimalists and Conceptualists, who took art away from a rather austere sense of itself and made it into something that could touch on almost every aspect of experience."

Influences and Connections

- Mark Grotjahn

- Sterling Ruby

- Liam Gillick

![Paul McCarthy]() Paul McCarthy

Paul McCarthy![Tony Oursler]() Tony Oursler

Tony Oursler- Raymond Pettibon

-

![Installation Art]() Installation Art

Installation Art - Post-Conceptualism

- Abject art

Useful Resources on Mike Kelley

- Minor Histories: Statements, Conversations, ProposalsBy Mike Kelley

- Foul Perfection: Essays and CriticismsBy Mike Kelley

- Mike Kelley: Interviews, Conversations, and Chit-ChatOur PickBy John Welchman, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw