Summary of Yōga

Following hundreds of years of self-imposed isolation during the Edo Period, Japan opened its ports to the outside world, causing a major influx of Western influences to infuse its national consciousness. This caused a race toward modernity as Japan strived to establish itself as a viable peer in the global arena. This push toward a fresh identity spurred one of the most important movements in Japanese art as some of its artists sought to detach themselves from the traditional realms of indigenous historical painting in order to create a new voice that better reflected integration into, and equality with, a contemporary world. Yōga art, or Western-style painting, became the key response to this impetus, made in accordance with European conventions, techniques, and materials, borrowing from important art movements of the time.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The rise of Yōga marked a historical rift in the psyche of Japan; a mirror of the process of change that posits the old versus the new. Its artists were seen as a new avant-garde, pushing toward modernity, while its opposition, specifically artists of the Nihonga genre who strove to retain Japanese styles while evolving its art, fought to preserve the country's distinctive aesthetics.

- The Western techniques utilized by Yōga artists were significantly different from Japanese art's prior aesthetics which largely included woodblock prints noted for flat color, bold outlines, singular planes, and aerial viewpoints, and Nanga works which drew inspiration from Chinese subjects, among others. These new techniques introduced the employment of perspective, a push toward oil painting, lithography, pastels, watercolors, sketching, and the practice of plein air painting, and the incorporation of decidedly Western motifs and subjects.

- Although Yōga adopted characteristics of popular movements of the time including Fauvism, Cubism, Impressionism, and Naturalism, its artists distinctively created works that not merely copied these other conventions but helped evolve the Japanese artistic oeuvre into a modern idiom.

- Yōga artists made a bold departure from Japan's traditional creative subject matter of the past, which had been primarily steeped in portrayals of everyday Japanese life, literature, and cultural mythologies, by introducing the concept of the artist as an individual with an independent voice and opinion amid the country's changing social and political climates.

- The cycle of Yōga's rise and fall remains an important indicator of art's role in documenting periods of noted transformation within a country. It remains an inspiration to Japanese artists today who continue to work in the spirit of balancing a respect for the past with the innovations of progression.

Artworks and Artists of Yōga

Salmon

This realistic work on paper focuses with sharply observed detail on a single salmon, a cord laced through its gills, as it hangs vertically against a cedar colored background. The upper part of the salmon has been filleted, displaying the reddish pink flesh cut down to the spine and bones. The vertical format of the work emphasizes the elemental form of the fish, the shadow outlining the fish, and the cord that holds it on the left to create a sense of depth, of the salmon partially suspended above the board. The remarkable texture of the skin in the lower part of the body is not only accurate but conveys a sense of daily life.

Yuichi felt that painting, through realistic depiction, could convey a sense of Japanese culture, and the image of a partially filleted salmon, prepared for guests, was a motif commonly used in small Japanese carved wood decorative pieces. Unlike the Western still life's emphasis on plenty, this work emphasizes a simple but essential element of Japanese life.

This painting received a great deal of attention when it was shown in 1877 in Kyoto and made a powerful argument for reviving Japanese art and making it equal to Western art. As art historian Michael Sullivan wrote, "Nothing quite like this had been seen in Japan before. Painted, like his still lifes of this period, with a new honesty and feeling for texture - he was the first to see Western oil painting as a means of expression - this is a key work in the birth of modern art in Japan, standing out in contrast to the labored imitations of European salon painting then in fashion."

Oil on paper - The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts, Tokyo, Japan

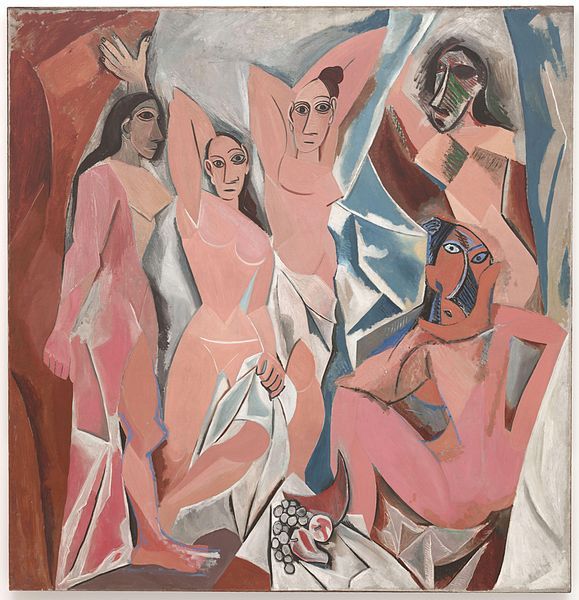

Spring Ridge

This landscape, reflecting the influence of the Barbizon School's Naturalism upon early Yōga painters, shows several farmers working with implements in the dark green furrows of their fields. The painting is horizontally divided into thirds between the fields, the thatched roofs of the village among the trees above, and a clouded sky, creating a sense of balance and of a life lived in harmony with nature. Curving lines - at the edge of the field, in the opening between the trees in the left middle distance, and the concave curve of the tree line - contrast with the diagonals of human activity and presence, marked in the furrows of the field and the ruts of the road. This use of line to create composition, dividing the pictorial plane into broad distinct areas is an essential characteristic of Japanese art, though here expressed through the Western form of oil painting. The dark earth tones of the fields and farmers create a feeling of intense and somber activity lightened by the presence of the white flowering trees that bloom along the horizontal center of the work and intensifying toward the whitish blue sky.

Asia's en plein air painting was influential not only upon other painters, but also upon Japanese writers like Massaoka Shiki who created a fresh approach to haiku, based upon contemporary realism, rather than worn literary allusions. Shiki called his haiku "sketching from life" and it became a dominant literary form in the early 1900s as literary magazines like Hototogisu encouraged submissions in the style.

Oil on canvas - Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan

A Maiko Girl

This painting depicts a maiko girl, a young woman trained in playing music to entertain guests, in a vibrantly colored silk kimono sitting on a bench in an open sliding partition. An older server woman in a greyish blue kimono is profiled on the right, her face turned toward the young woman, as if in a moment of interrupted conversation. The young woman is framed by the open partition and the vibrant pond behind her, its blue and violet punctuated with yellow and white. Kuroda's Impressionistic use of vibrant color and light effects changed Japanese Yōga painting from its previous somber palette derived from the Barbizon School. At the same time, his subject is very much within the Japanese tradition of bijin-ga, images of beautiful women that often focused on maiko girls and geishas.

In the 1880s Kuroda spent almost a decade in France, studying art with Raphael Collin. When he returned to Japan in 1894, he said, "Visiting Kyoto, I had a feeling of coming to a strange country named Japan which is outside of the world," and he said of the maiko girls of Kyoto, "I have the same feeling as Westerners who describe Japanese females as pretty small birds. They look like very rare, pretty and fragile decorations." With her bright clothing and posture, the young woman does convey a sense of a brightly colored bird having just alighted, and the decorative effect appealed to both a Japanese audience, accustomed to bijin-ga, and to Western tastes inclined toward Japonism that favored the exotic and decorative elements of Japanese art. Nonetheless, the young woman with her right arm extended to the railing and her left on the frame of the partition as if having just opened it, and her vibrant direct expression, seems full of confidence and authority. What the artist conveyed here was a kind of intimacy, as the work, creates a sense of communicable feeling between the two women. A young Japanese artist Kobayashi Mango described the effect of encountering Kuroda's work, " It is like a feeling of seeing a ray of light all of sudden while walking a dark field path. Surprisingly, it was not just me thinking like this."

Oil on canvas - Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan

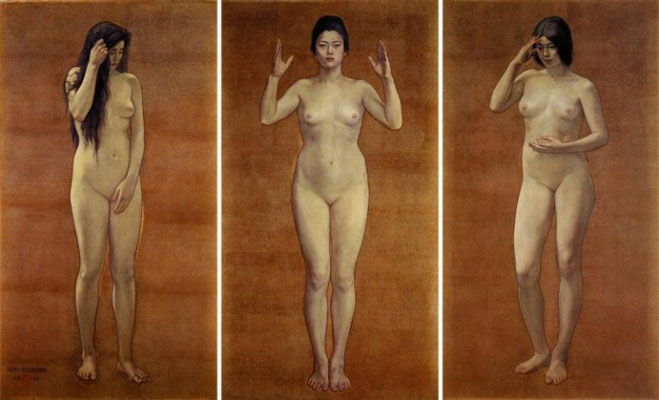

Chi Kan Jo (Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment)

This triptych depicts three nudes, which symbolize, from left to right: Sentiment with her right hand touching her hair, Impression with both hands raised to head level, and Wisdom, her right hand touching her brow. Only Impression in the center panel faces forward, looking toward the viewer, while the other two women turn slightly toward her, their gazes looking down. The simplified composition combines a three-dimensional naturalistic, figurative treatment with the Japanese ma, or negative space of the gold background traditionally found in byobu, or folding screens. As a result of the non-naturalistic background, the symbolism of the figures is enhanced. The concepts these figures embody were derived more from the artist's own thinking, rather than correlating to any Eastern or Western definition, and by presenting a triptych, often reserved for religious subjects in Western classical art, he intended to convey a sense of the timeless and sacred, embodied in these figures.

The painting was created in Japan, following Kuroda's return from Paris, and after he had been named a professor of Yōga at the Tokyo School of Fine Art. It was, in a sense, his artistic argument in favor of the nude as a subject for Japanese art following the controversial showing of Morning Toilette. In Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment, he drew upon not only the Western tradition of the nude, but upon the French Neoclassical tradition of the nude within an allegorical context, and combined it with the gilded backgrounds of traditional Japanese folding screens.

The work was shown in Japan at the 1897 2nd Hakuba-kai Exhibition and, subsequently, at the Paris 1900 International Exposition where it was awarded a silver medal. To his Japanese audience, the nude itself was controversial, and the attribution of abstract qualities to each of the figures only added to the controversy in contrast to European tradition where allegorical treatments made the nude more acceptable. Even the process of creating the painting was pioneering, as Kuroda introduced the practice of working from a live model, and employed for the first time, a Japanese model to create the nude. Kuroda's work and teaching was widely influential, as he introduced Western subjects and approaches, leading to his being dubbed, "the father of modern Japanese western-style painting."

Oil on canvas - Kuroda Memorial Hall, National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo, Japan

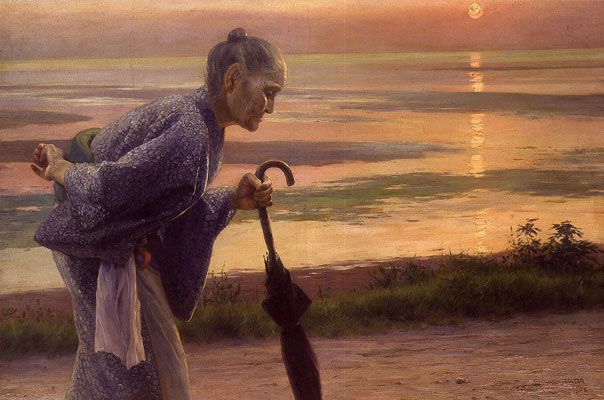

Old Woman

This painting, depicting a radiant body of water beneath a setting sun, focuses on the single figure of an old woman, bent in profile on the right, her left hand gripping her long umbrella as if it were a cane, while she focuses on the path in front of her feet. She walks along a dirt road, bordered by grasses, plants, and a bit of shore that gives way to luminous gold and rosy waters, illuminated by the horizontal line of the sun's light intersecting the canvas on the right. The contrast between the flowing forms of water and land and the upright form of the woman and vertical line of reflected sun suggests the transitory nature of human life. The woman ignores the sublime view, focusing intently at the step before her, and the setting sun alludes to her age, still leaning forward into the flow of the water and road but already bent by natural forces.

The painting's subject, a humble person in an ordinary activity, draws upon the Edo period's portrayal of everyday life and Japanese leisure activities Yet, this work's effect is almost photographic, and shows the influence of Jules Bastien-Lepage's Naturalism, to which Wada as part of the first graduating class of the Tokyo Art School's Western Painting Department was introduced while studying with Kuroda.

Oil on canvas - National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan

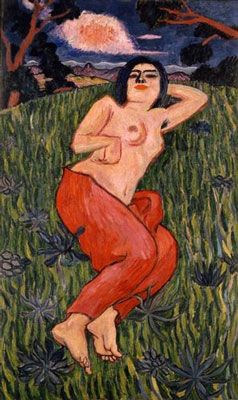

Nude Beauty

A woman, nude from the waist up, reclines on a grassy hill with her left arm bent at the elbow behind her head, and her body turned sideways as her face turns toward the sky. The red boughs of trees frame either side of the high horizon at the top curve of the hill, where a colorful vista opens beneath a dark blue sky with a prominent pink cloud. Everything in the composition, the high horizon, color palette, simplified forms, and vertical lines of the grass that move like flames, draw the viewer's gaze upward to the woman's face. Portrayals of beautiful women were an important genre of ukiyo-e and Japanese painting, yet the nude sensuality of this figure and Fauvist hues drew upon the Western tradition.

The woman's pose echoes Henri Matisse's Blue Nude (1911) and the energetic lines reflect the influence of Vincent van Gogh. This painting launched Yorozu's career when he presented it for his thesis painting at the Tokyo Art School, and the dramatic color palette made this work controversial for its non-naturalistic treatment and sexuality. Displaying the rebelliousness against the academic status quo that permeated his career, the artist not only boycotted the exhibition of his work but also refused his graduating teacher's certificate. The work has been heralded as the first Japanese Fauve painting and a great influence on Japanese Fauvist Expressionism, as the art historian Matthew Larking wrote, making the artist "the most representative Japanese expressionist painter of his age."

Oil on canvas - Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan

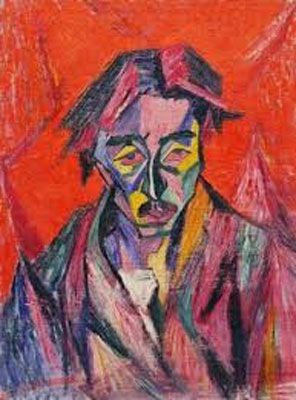

Self-Portrait with Red Eyes

This self-portrait, using a Fauvist palette in a Cubist treatment, depicts the artist against an intensely red background, as sharp angles and diagonals create his figure. His red eyes are triangular shapes, which further emphasized by the triangular yellow bordered by black and blue, appear intense yet exhausted, as the yellow droops toward his cheekbones. It is as if the artist has taken on the energy of the environment, saturated with red, its black and dark lines and diagonals creating a sense of aggressive commitment. With its unflattering treatment, designed to show the subject's sensibility, this image draws upon the Japanese tradition of the self-portrait that often exaggerated features in order to convey character.

Tetsugoro's work first introduced elements of the European avant-garde to Japanese artists in images like this one that fused several different styles. As the art critic, Michael Brenson said of this work, "With his droopy, vigilant eyes, this disheveled, defiant, self-conscious figure, part Cubist, part Expressionist, both confronting us and pinned to the red background, reflects the kind of determination and introspection typical of Japanese painting at the time...there is a will and confidence that artists of the previous generation did not have."

Oil on canvas - Iwate Museum of Art, Iwate, Japan

Road Cut Through a Hill

This canvas is particular for its point of view - as if confronting and looking up the steep road, its ascension is emphasized by the rock wall and its upper railings on the left and the angular shapes cut into it on the right. Closely cropped and emphasizing spatial relationships, created by vertical diagonals extending toward a v-shaped horizon with its deep blue sky, the painter said he desired "to directly face the mass of nature itself." Having studied the Western masters for a period of time, the artist wanted to return to the subject of nature, and here takes a road near his home as a kind of monumental subject.

Kishida began his career, influenced by the Barbizon school's Naturalism, but then studied with Kuroda who introduced him to the brighter palette of Impressionism. His artistic evolution took another turn with exposure to the works of Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne. Around 1914 he began to study the works of Rembrandt, Van Eyck, and Dürer, creating works like this one, highly representational, using earth tones with strong highlights and precise detail. In effect, his landscape becomes a study of elemental forms and mass, employing a unique style. As the art critic Matthew Larking wrote, "Ryusei Kishida...remains a giant of modern Yōga, though his idea of 'modernism' would mostly have been unrecognizable to his Western counterparts."

Oil on canvas - Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan

Standing Self-Portrait

This self-portrait emphasizes the vertical form of the artist, standing in the middle of a road that dramatically narrows along its diagonals behind him, jagged dark trees and rocks lining each side. The figure looms above the landscape up into the sky, but seems also ravaged, as if emblematic of a ruined tower. He holds a painted covered palette in his left hand and a brush hangs, perhaps uselessly, from his right hand. The sky is scratched and rough, blotched by a jagged blue on the right of his head, and the artist's face is similarly gouged, his expression darkly outlined, his face grim. The work seems scraped into the canvas and conveys a feeling of desolation and trapped intensity. On the back of the canvas, Saeki subsequently painted another image, Notre-Dame at Night (Mantes-la-Jolie) (1925), where the cathedral, gouged in dark turbulent colors, similarly reflected the artist's despair at the difficulty of fitting into either the art world of Paris or his native Japan.

Saeki had moved to Paris in 1924 where he studied at the Académie de la Grande and was influenced by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Maurice Utrillo. This particular painting followed from his meeting with the French artist, Maurice de Vlaminck, in 1924. He showed de Vlaminck what he felt were his best works, and when the French artist dismissed them as academic, the criticism precipitated a turning point and innovation in Saeki's work. Subsequently he painted this image using an aggressive brush stroke and scraping the canvas with a palette knife, creating a signature Fauvist Expressionist work. At the same time, the overall effect created by the carved and incised surface is reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints.

Oil on canvas - Osaka City Museum of Modern Art, Osaka, Japan

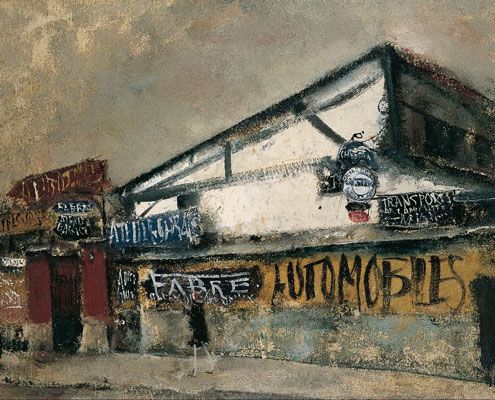

Garage

This work, painted toward the end of Saeki's life, depicts an automobile garage in Paris. Its strongly outlined diagonals, intersecting a scraped grey sky, convey a powerful effect of urban ruin. The reductive color palette of red and yellow, contrasting with the white, black, and varying shades of grey, is roughly applied and scraped, so that the scrawled lettering of the signs have a graffiti-like effect. A woman, wearing a black dress and a hat with a touch of red, walks down the sidewalk in the otherwise empty scene. Her legs are thin streaks of white, and she seems almost an apparition, on the verge of fading into the black and white "FABRE" above her, as the artist suggests the doomed frailty of human effort and presence, in a scoured world.

Saeki died in a mental institution, suffering both from tuberculosis, and having had a mental breakdown. As the New York Times art critic Michael Brenson wrote, " When Saeki Yuzo, who is perceived in his country as a tragic hero, the Japanese van Gogh, died at the age of 30 in an insane asylum in Paris in 1928 - perhaps a suicide - he had been trying to paint in this void. Saeki continues to be an example to Japanese artists abroad of the difficulties in reconciling East and West."

His work had a noticeable impact on subsequent avant-garde artists, as the art critic Matthew Larking wrote, "In France, Saeki was a progeny; in Japan, an innovator... Saeki's essential contribution, while very short-lived, was to usher in a period in Japanese Modernism that overthrew the pre-existing reliance on the Impressionist model and encouraged freer Fauvist Expressionism."

Oil on canvas - Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

Portrait of Chin-Jung

This full portrait depicts Mrs. F. Chin-Jung, Odagiri Mineko, the daughter of the President of the Bank of Japan who was also a painter himself. Yasui's portrait was somewhat controversial in its time, as rather than conveying his subject as an ideal representation, in the tradition of bijin-ga (images of beautiful women), he conveyed her distinctive features and her individuality. Accordingly, the subject here is self-confident, and powerful, her body leaning back in her chair, and sitting, purposefully, looking ahead, without attempting to look at or charm the viewer.

The image is closely cropped, as only a sliver of reddish purple wall is left above her head, and her left foot extends outside the frame, suggesting that the figure directs and fills the space she occupies. The blue of her dress with its white pattern both unifies and invigorates the image, accentuated by the varying lighter blue and white swirl of the fabric that she sits upon. The chair creates a kind of sense of volume by its contrast between its solidly colored rungs and those that create a more sketch like effect.

The artist uses bold outlines and broad area of colors, drawn from traditional Japanese art, while creating a realistic, and sharply perceptive portrait in the Western tradition, creating a work with both authority and dissonance. As Brenson has noted, "Yasui Sotaro...indulges in disequilibrium and pleasure."

Oil on canvas - Tokyo National Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

Mahiru no kao (Face in Midday)

This canvas overflows with a Cubist inspired face, though depicted in dynamically fluid and curved overlapping planes, rather than sharp angles. Both the fluid lines and the resulting decorative effect are rooted in a traditional Japanese aesthetic, translated into a modern idiom. The face, rendered in a vibrant color palette, conveying the bright sun of midday, tilts to the left under a dark green hat, reminiscent in its color of military uniforms. Prominent eyes glance down toward a magazine open to colorful art images just below the flaring end of the nose, and in the upper right, a red cobbled street, white door, and part of a blue building with a red tiled roof are partially visible beneath a dark blue suggestive of the sky. While the work is energetic in color and line, the overall effect is dissonant, suggesting a person overwhelmed, an effect emphasized by the green and black outlines around the eyes, and their fractured gaze. What the artist suggests is a kind of modern hyperactivity, which stuns the individual, behind whom the dark blue lines of the sky suggest the weight of the past.

This work was exhibited in the 1st Modern Art Exhibition of the Modern Artists Association of Nippon, where Okamoto's Yushu (Melancholy) (1948) was also shown. At this point, Okamoto in his promotion of the avant-garde to challenge the stasis of society often employed garish colors, as he said, "the stone-age of art is finished," and compared the art world to "a Galapagos-like" realm enthralled by the past. As a result, while this work exemplified Japanese Cubism, it also influenced the formation of a newly emerging post-war Japanese avant-garde.

Oil on canvas - Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki, Japan

The Tale of Akebono Village

This Surrealist image, which is reminiscent of woodblock prints depicting rural life, portrays Akebono Village, where a dispute with a landlord has led to the murder of an activist, and a grandmother has committed suicide after being tricked into bankruptcy. The grandmother is depicted on the right, hanging from the beamsThe dog, standing on its hind legs, carrying a satchel, and wearing a bow around its ears, is a Surrealist depiction of her now orphaned granddaughter. The murdered activist lies in a pool of blood where various fish lift their heads out of the water, while his severed arm holding a sickle rises out of the pool. A farmer with one hand on his hip and the other on the handle of his shovel stands above the man, and another man wearing an expensive silk shirt and vest, his head shrouded in white, kneels behind him, his left arm holding a weapon. In the background a green field, spread out like an inverted fan, extends toward the flat black mountains and in the field, a dog-like farmer carries his burden. The image is remarkably compressed, its planes and diagonals creating a sense of momentum as events collapse in a claustrophobically oppressive world. No one has a human face here, as some have been transformed into dogs, others disfigured by injury, and the faces of those who have carried out the violence are hidden. A multiple-faceted gaze is created by the shocked whites of eyes - of the fish, of the single protruding eye of the dead man, and in the fearful and submissive eyes of the dogs - to convey a sense of shock but also of the fracturing of human identity.

Prior to World War II, Kikuji had studied art with the noted Surrealist Japanese artist Fukuzawa Ichiro and been influenced by Max Ernst, Hieronymus Bosch, and Salvador Dalí. He was drafted into the military in 1939 and fought in China. After the war, his art was profoundly preoccupied with the horrors that he had seen and participated in during the war. Becoming an activist, he went to the village at the request of the Cultural Brigade of the Japanese Communist Party to make a kamishibai, a narrative told with a number of storyboards and accompanied by narration, but instead created this hallucinatory work that conveyed not only the story in a single image but the disturbing social reality.

Oil on dungaree - Gallery Nippon, Tokyo

Quo vadis

This Surrealist painting depicts a bleak and empty landscape, most of it rendered in a broad area of white, except for the blue raincloud on the upper right that streaks the sky, falling upon a distant city, and a winding procession of people in mid left. In the center of the painting, his back to the viewer, a repatriated soldier wearing a worn suit and crumpled hat, a rucksack over his shoulder, and a book under his left arm, stands between a large snail shell on his left and a two-directional blank marker on his right. The marker has multivalent associations, as it points in two directions, both of which, in the context of the empty space, seem meaningless. With the cluster of rocks and two flowers at its base, it could mark a grave or the scene of a death, and its shape also resembles a cross and the shape of a kamikaze plane flown into the earth. Closer inspection of the winding procession shows the red flags of some kind of demonstration, driven by unknown purpose. The man is perhaps a self-portrait, reflecting that the artist was searching for direction, the "where are you going?" of the work's title, as he faces the emptiness of the post World War II world. The shell, representing a self-enclosed isolation, contrasts with the outward pointing marker, but the man seems stalled and indecisive as he confronts the view ahead, defined by the use of negative space.

Like a number of Japanese artists, Kitiwaki began exploring Surrealism in the late 1930s, at the same time Japan was moving toward ultra-nationalism. Kitiwaki combined his wide interests in natural science with exploration of ancient traditions like the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination system. This later work shows his characteristic juxtaposition of ordinary objects to create dissonant and disorienting images, as Ritter said, he is "first and foremost a realist who believed that Surrealism could provide the means and methods for unlocking hidden meaning in the world as it exists - not its imagined alternative."

Oil on canvas - National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan

Beginnings of Yōga

Early Contact with the West

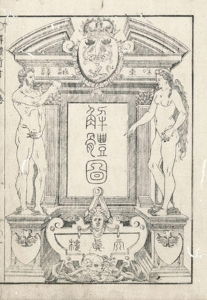

The earliest introduction of foreign religious paintings and imagery to Japan came via Christian missionaries with the arrival of the Portugese in 1543. At the time Japanese artists copied and imitated the works, though that interest declined in the following Edo period when Japan cut off all contact with the outside world. Only one port remained open, allowing for limited trade with China and the Netherlands. It was through this channel that Japanese artists discovered perspective by studying Dutch anatomical and scientific textbooks. As a result, some of them incorporated the technique into their own work, like Utagawa Toyoharu in his Perspective Pictures of Places in Japan (c. 1772-1781). Elements of this new perspective began influencing the dominant art style of the time, Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, particularly as seen in the work of Katsushika Hokusai.

Commodore Perry

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy arrived with a fleet of warships with the express purpose of forcing Japan out of its two centuries long isolationist stance and into an open policy. The powerful display of firepower caused a crisis in the Japanese national consciousness. Aware of the West's superior technology, the government spurred various initiatives to explore Western science and art so that Japan might become an equal of the West. Accordingly, the Bansho Shirabesho, (Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books) was founded in 1857 in order to translate foreign books into Japanese.

The artist Kawakami Togai was put in charge of a section devoted to the study of Western art, where, instructed to learn Western art techniques, he taught himself linear perspective and explored oil painting. The artist Takahashi Yuichi became his student and assistant. Together, the two men developed a system for drawing with pencil that was adopted in all Japanese schools for over a decade, replacing traditional brush and ink.

After the Meiji Restoration government gained power in 1868, Togai started his own private art school teaching Western painting and subsequently published his A Guide to Western Style Painting (1871).

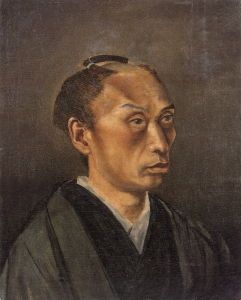

Takahashi Yuichi

Takahashi Yuichi is considered to be the first true Yōga painter, not only mastering the technique, but also employing its aesthetic. He first encountered Western art in the form of Dutch lithographs while he was studying art in the Kanō school, and found in the works a realism and directness that led him to oil painting. He felt that Japanese art was stagnant, its ukiyo-e "bent on vulgarity and insignificance," and the Nanga traditional style in homage to Chinese culture, too esoteric. Following his work with Togai at the Bansho Shirabesho, he went to Yokohama in 1867 to study with Charles Wirgman, a British cartoonist and artist, who was so impressed with Takahashi's work he supported the young artist's exhibition at the 1867 Paris World Exhibition.

Meiji Restoration Government and the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko

The Meiji Restoration government formally took power in 1868, headed by the Emperor Meiji. Driven by the understanding that the former Edo government had been destabilized by the arrival of Western influence, the government's fundamental policies involved the modernization of Japan. These initiatives also extended to art.

Anxious to compete with the West, the Meiji government followed the Western model of establishing art academies and technical schools by creating the first official art school in 1876 with the opening of the Kobo Bijutsu Gakko (Technical Fine Arts School). The government recruited three Italians, Vincent Raqusa to teach sculpture, Giovanni Cappelletti for general preparatory courses, and Antonio Fontanesi to teach drawing. Antonio Fontanesi, a painter influenced by the French Barbizon School, taught oil painting, en plein air (painting outdoors), drawing or painting from a live model, anatomical studies, perspective, and the use of pastel, charcoal, and crayon.

As a result of his early leadership in Western painting, Takahashi Yuichi was also appointed by the Meiji government as an art professor at the Kobubijutsu Gakkō (Technical Fine Arts School) in Tokyo, where he worked with Fontanesi in promoting Western art. Yuichi argued that the revival of Japanese art via Western styles would also help create a modern sense of Japanese national identity, saying, "If the virtues of its heroes, saints, and sages, were disseminated by portraits drawn from living models, if in times of peace the national folk dances and music were illustrated and if the armies and battles were depicted during the war, so that people even thousands of miles away could visualize what happened."

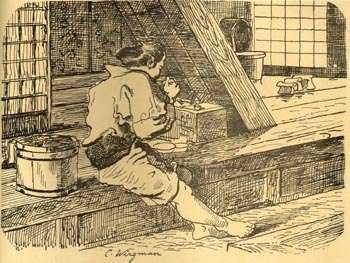

Charles Wirgman

The British artist Charles Wirgman made a noted impact on the development of Yōga as he taught Western art techniques to a number of students, including Takakashi Yuishi and Hosui Yamamoto. Wirgman, working for the Illustrated London News, came to Japan in 1861 and settled in Yokohama for the rest of his life. He was a noted cartoonist and illustrator and in 1862 launched the first Japanese magazine, Japan Punch, a humorous and satirical monthly publication meant for foreigners living in Japan. Wirgman not only taught Western art but also was an important bridge between Japan and Europe, helping to promote the works of Japanese artists in France and creating intercultural connections that emphasized European art studies. As a result, artists from the following generations, such as Kuroda Seiki, Yorozu Tetsugoro, and Yūzō Saeki, would go to Paris for extended periods of study.

The Barbizon School and Kuroda Seiki

In 1883, Kuroda Seiki went to Paris where he studied with Raphael Collin, a French artist whose works, shown at the Paris Salon, had begun to achieve success for their Academic styles. Collin also taught other Japanese artists like Fuji Masazo and Asai Chū. While the era was marked by the emergence of Impressionism, Collin's style was more influenced by Neoclassical Academic painting and by the Naturalism of the Barbizon School, and by Jules Bastien-Lepage, who was a close friend of Collin.

Accordingly, while Kuroda and other Japanese artists who studied with Collin were influenced by Impressionism's emphasis on light and color, they did not adopt the vigorous brushwork or technique of that movement, but sought to bring more color into naturalistic treatments. While studying with Collin, Kuroda began visiting Grez-sur-Loing, a village outside of Paris that had become a sort of informal artist's colony, and creating plein-air paintings, of which his Grez (Withered Field), c.1891, was a noted example.

Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society), 1889

By the 1880s the pendulum between Japanese style painting and Western style painting, both seen as competing ways of creating an international and national artistic identity, had swung away from Yōga to favor Nihonga art. Nihonga art originally arose as a rejection of the adoption of Western techniques, and as a preservation measure to honor and respect traditional Japanese styles and aesthetics while also forwarding them into a more modern sensibility. As a result of this backlash, the Technical Fine Arts School closed in 1883. This shift also reflected the views of the Meiji government, then responding to an increased anti-Westernism in Japanese society. In response to the closing of official venues, Yōga artists established the Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society) in Tokyo in 1889 to continue to promote the teaching of Western painting.

Returning from France in 1893, Kuroda Seiki joined the Society where he played a leading role. He helped revive the movement by bringing new techniques and subject matter into the fold, particularly plein-air painting and the nude. As a result, by 1896 a department devoted to Yōga was again added to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and the movement was reconsidered a viable part of Japanese art.

Bunten

In 1907 the Bunten, the official annual art show, was established by the Ministry of Education to provide a venue for creating a sense of national artistic identity. Japan had been victorious in the Russo-Japanese War from 1904-1905 and, having become recognized as an international power, the government saw art as another way to consolidate that recognition on an international stage. Of equal importance to creating a sense of national identity was creating a public awareness of Japanese art. Previously in Japan, art had been something that people would have to travel to temples to view. Only the ukiyo-e work of the Edo Period had really reached a public audience. The Bunten showed art in three categories: Yōga, Nihonga, and sculpture. Each category was presided over and judged by representatives of each type of art.

While the Bunten did create a public audience for art, evidenced by the 250,000 people in attendance, many artists came to feel that the official show was both too politicized and conservative. In 1912, Nihonga artists protested, resulting in the creation of two sections for Nihonga, the conservative Ikka (First Section) and the progressive Nika (Second Section). In reaction to this, Yōga artists Yamashita Shintarô, Ishii Hakutei, and others established the Nikakai, or Second Section Association, in 1914. The annual show, competing with the Bunten showed only work by independent and avant-garde artists, and is still a noted venue today.

Yōga: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The Nude

The nude had never really been a subject for Japanese art, as it had in the West. Japanese artists had sometimes depicted nude women in communal bathing scenes but the emphasis was upon the ordinary activity, distinctively non-eroticized. Even in ukiyo-e's shunga (pictures of spring) works that depicted sexual activity, the couples were always portrayed clothed to indicate their social role and caste, exposing only their unusually exaggerated genitalia. Just as shunga originally shocked Western audiences, the Western tradition of the nude as an aesthetic or erotic object shocked the Japanese. Scholar Basil Hall Chamberlain wrote in 1890, "The nude is seen in Japan but not looked at." Accordingly, the first paintings by Japanese artists to depict Japanese women in the tradition of the Western nude were highly controversial. Kuroda Seiki showed the first noted Japanese nude, his Morning Toilette (1895), at the 4th National Industrial Exhibition in 1895.

Many critics were outraged and agreed with the title of a subsequent article "Keep Nude Paintings a Secret," as the author Miyako Shinbun went on to say, "...when it comes to displaying it in front of the general public, it is absolutely disgraceful. Such artists are devoted to their own theory of art and have forgotten their influence on social customs and manners."

Kuroda, however, continued advocating for the nude and implicitly connected the genre to Japan's attaining international artistic stature, saying, "I cannot think of any reason to abandon nude painting. There is nothing wrong with the international standard of aesthetics. It is actually necessary and should be promoted for the sake of the future of Japanese art." Kuroda's work and teaching influenced many subsequent artists, including Sotaro Yasu, Narashige Koide, Ryuzaburo Umehara, and Tetsugoro Yorozu. The genre of the nude was particularly important in the development of subsequent avant-garde movements.

Fauvist Expressionism

An early and dominant avant-garde strain of Yōga in Japan combined Fauvism's intense and sometimes garish color palette with Expressionism. Fauvism had a noted influence on a number of Yōga painters, and the scholar Kawakita explained, "the subsequent trend through postimpressionism to fauvism represented in many ways the rebirth of the freedom that had been seen in the Nanga and Maruyama-Shijo styles of Japanese painting. To Japanese eyes, in short, it required nothing of the 'wild beast' to appreciate the fauves. On the contrary, it was like coming home again. In the fauvist medium the Japanese artist could simply let his Japanese self go."

The leader of the avant-garde in Yōga painting was Yorozu Tetsugoro, whose Nude Beauty (1912) first introduced Fauvism to Japanese artists. In his evolving artistic idiom, he followed with his Self-Portrait with Red Eyes (1912-1913) where the Fauvist palette had been employed in an expressionistic work. The Fauvist palette continued to be a dominant trend in Japanese art, as seen in works like Umehara Ryûzaburô's Nude (1932) or Nude with Fans (1938), which made him one of the most successful painters of his era. Other Japanese artists combined Fauvist colors with other styles, as seen in Tarō Okamoro's Cubist Mahiru no kao (Face in Midday) (1948).

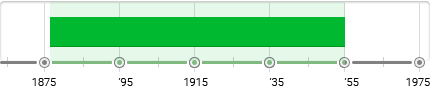

Cubism

Although at the time Cubism was a leading movement in Europe, only a few Japanese painters were under its influence. Yorozu Tetsugoro encountered the movement when he was living in Paris, and his Leaning Woman (1917), the first noted Cubist Japanese work, introduced the movement to Japan. Nonetheless, Tetsugoro's painting showed a Japanese emphasis on line more than refracting angles, and in the 1920's, Cubism was more accurately one of many sources of inspiration than a distinctive trend. In the following generation, Tarō Okamoto, a Yōga painter who had studied at the Tokyo Fine Arts School, became an important bridge between abstract art, Cubism, and Surrealism. Moving to Paris in 1930, he was part of the Abstraction-Création group from 1933-1937. While in Paris, he was influenced by Pablo Picasso's work, and in the period following World War II, his works like Mahiru no kao (Face in Midday), (1948) helped spark a new interest in Cubism.

Only in the 1950s, following a 1951 retrospective of Picasso's work in Tokyo and Osaka, did Cubism become a major trend in Japanese art. Picasso's politically themed work was of great interest to post-war Japanese artists like Taro Okamoto, Masaaki Yamada, and Yamamoto Keisuke. They were driven to respond to the horrors of World War II, including the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Both Keisuke's Hiroshima (1948) and Mikami Makoto's Night (1949) were deeply influenced by Picasso's Guernica. As art historian Inhye wrote, "Picasso made many artists in Asia think about and render their way of life as an artist, encouraging participation in and response to political issues."

Surrealism

Surrealism began in Japan in the late 1920s as a literary movement. The first Japanese surrealist poetry magazine was launched in 1927 and the leading Japanese Surrealist poet, Nishiwaki Junzaburō, returned from Europe in 1928. Art soon followed, and Kara Harue, Abe Kongo, and Tōgō Seiji exhibited Surrealist works at the 1929 Nikakai exhibition. Takiguchi Shūzō, a poet and art critic, who translated André Breton's La Surréalisme et la peinture in 1930, which had a noted impact on the Japanese art world, believed that Surrealism "has permeated our daily lives since the time of our ancestors." He saw the Japanese traditions of Zen, haiku, and other Japanese art forms as reflections of an intrinsic Surrealist spirit in Japanese art.

Returning to Japan from his art studies in Paris in 1931, the Surrealist Fukuzawa Ichirō gave further impetus to the movement. In that same year, a noted exhibition of Surrealist works that included Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Hans Arp, Yves Tanguy, and many others toured Japan. As a result, clubs and societies devoted to the movement formed throughout the country. Also in 1931, a photographic exhibition of German photographers, a number of them Surrealists, toured Japan and a New Photography movement was launched led by Yamamoto Kansuke, Hirai Terushich, and Nakayama Iwata, involving photographers in Osaka, Kobe, Nagoya, and Tokyo. Taiguichi Shūzō's 1937 Surrealism Overseas exhibition further consolidated the movement, as he said, "Surrealism should not be considered just another Western modernism but a vital force that could revive the creative and artistic force of Japan."

For many artists Surrealism allowed the development of an individual artistic sensibility, increasingly under pressure from rising nationalism. As art historian Gabriel Richard Ritter wrote, "surrealism offered an escape from the increasingly oppressive atmosphere of wartime Japan, as well as a method to critique reality and society. Surrealism in Japan can be viewed as both a refuge and an anti-establishment practice to explore artistic subjectivity while resisting the ideological pressures of the state." By 1941, the government began using "thought police" to keep surveillance upon and arrest artists whose art was counter to national interests. Nonetheless, Surrealism continued to be an active movement in Japan, often fusing with other movements in terms of style.

Reportage

Reportage began among Japanese artists following World War II, and reflected a strong sense of social protest and commentary. Japan was occupied by the United States military following the war, and artists wanted to expose the oppression of the occupation, the effect of the war upon Japan, and Japan's own culpability in the horrors of World War II. Reportage used a style that varied between elements of Social Realism and Surrealist imagery. Nakamura Hiroshi's work exemplified the social realist approach in works like Sunagawa #5 (1955) that also drew upon Japanese graphic and woodblock styles. Nakamura described his intent, "In the early 1950s, socialist realism was spreading throughout the world as an art movement and many art students were influenced by it... We were encouraged to persuade the viewer." The signature work of the Reportage movement became Yamashita Kikuji's The Tale of Akebono Village (1952) with its surrealist imagery depicting a violent scene in a rural village in the Yamanashi prefecture.

By the mid-1950s Reportage became deeply linked to protest art. When the United States conducted thermonuclear bomb tests at Bikini Atoll, Tatsuo's 10,000 Count (1954) protested with an image showing the irradiated catch of a Japanese fishing boat. Other artists associated with the movement were Nakamura Hiroshi, Yamashita Kikuji, and Ishii Shigeo, and their protest work continued into the 1960s.

Later Developments - After Yōga

Yōga art based upon Western techniques, styles, and motifs is still taught in contemporary Japanese art departments, and innumerable artists deploy its strategies in their work. Nonetheless, as a distinctive category, defined by oil painting, Yōga declined by the mid-1950s, as Tokyo was transformed into an international art center, principally known for its New Avant-Garde. The earlier avant-garde Yōga artists, who had worked in Surrealism, Reportage, or Cubism, had an inspirational influence upon the New Avant-Garde, and those artists who were still working like Okamoto Taro and Nakamura Hiroshi became leaders in the Tokyo art world. Working across a wide range of media, including video, graphic design, sculpture, and painting, artists like Ay-O, Shioni Mieko, Tetsumi Kudo, and Yoko Ono both initiated and participated in international art movements. Yōga painters associated with Abstract Expressionism, Color Field painting, Fluxus, Pop art, or Neo Dada, became part of the global art movement, rather than confined to a specifically Japanese category of Western style art. Nihonga artists in Japan were also influenced by the avant-garde Yōga artists and began to incorporate new materials, like acrylic paint, new contemporary motifs, and Western-derived influences into their work, and as a result, the distinction between Nihonga and Yōga became increasingly blurred. The major Yōga movements like Surrealism continue to attract artists of later generations, as seen in the works of Tesuyda Ishida such as his Prisoner (c. 1999) showing his head as a child emerging from the side of a school that confined him. Reportage has recently seen a revival of interest, as shown in Linda Hoaglund's acclaimed documentary ANPO: Art X War (2010), focusing on the artists of the movement.

Useful Resources on Yōga

- Maximum Embodiment: Yōga, the Western Painting of Japan, 1912-1955Our PickBy Bert Winther-Tamaki

- Fovisumu to kindai Nihon yoga = Fauvism and modern Japanese paintingOur PickBy Tokyo National Museum of Art

- 6: Meiji Western Painting (Arts of Japan) (English and Japanese Edition)By Minoru Hirada

- Mirroring the Japanese Empire: The Male Figure in Yōga Painting, 1930-1950 (Japanese Visual Culture)By Maki Kaneko

- Masterpieces from the Collection: Modern Japanese Western-style PaintingBy Ishibashi Foundation

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI