Summary of Oskar Schlemmer

Schlemmer's work in the arena of performance was both experimental and subversive. He purposely broke free from the usual constraints and rules of theater and dance, creating completely new versions of the artforms. He was one of the first artists to modernize the genres and his work formed the basis for many modern performance ideas that followed. He also explored painting and sculpture, winning international acclaim for his work and, as a result of this, he was commissioned to produce a number of high-profile murals including a series for the Folkwang Museum in Essen. During the 1920s, he was one of the Masters at the progressive Bauhaus school, working and teaching across a range of mediums. The Bauhaus revolutionized the way in which art was taught and created and Schlemmer is seen as a key figure in shaping its forward-thinking and collaborative ethos.

Accomplishments

- Schlemmer was novel in bridging the gap between pure abstraction and representational art. Whilst his work was predominantly abstract, he retained elements of the physical structure of the human body in his paintings, sculptures and performances. He presented people as architectural forms, simplifying the human image and breaking it into its constituent parts.

- His theater and dance work combined his interest in the representation of the human body with kinetic studies and an investigation of the relationship between performer and space and he transformed his observations into abstract geometrical and mechanical choreography and costumes. The most famous of Schlemmer's works, The Triadic Ballet (1922), is an important example of this process in action.

- Schlemmer's work aligned with Bauhaus thinking on merging art and technology, man and machine. His paintings often present genderless automatons and his dancers moved in unusual and machine-like ways. In relating humans to machines, Schlemmer was at the forefront of a movement to utilize technology to seek a deeper understanding of the human condition.

The Life of Oskar Schlemmer

Despite the fact that Oskar Schlemmer's Triadic Ballet was first shown in 1922, his multi-media design aesthetic remains avant-garde today. The video to Lady Gaga’s hit Bad Romance reimagined the German artist’s choreography a century on, to critical acclaim.

Important Art by Oskar Schlemmer

Relief H-6 PA

Schlemmer's reliefs mark a half-way point in his exploration of the human body from two-dimensional paintings to three-dimensional sculptures. His negotiations with Cubism are also apparent as he divides the human figure into geometric sections. The viewer sees the figure from the front and the rounded shapes denoting the head, torso, and legs are intersected with horizontal and vertical gridlines. These elements of the body are raised from the surface, but also delineated through the use of metallic paint in black, brown, silver, and bronze. Patterned sections make the figure stand out from the surface and offer more depth to the relief.

Reliefs were a medium that many artists of this time experimented with including Hans Arp, whose wooden reliefs of the 1910s and 1920s raised geometric shapes beyond the confines of the two-dimensional canvas. Schlemmer's relief works also exhibit many similarities to the Wall Pictures of his friend Willi Baumeister. Relief H-6 PA can be seen as Schlemmer's attempt to reinterpret the European avant-garde, and particularly Cubism, along the lines of his own fixation with the human figure. In his move towards sculpture through his experimental reliefs, the artist was able to reconsider the body's relationship to space, and utilize geometry for anthropomorphic rather than abstract ends. This work foreshadows Schlemmer's use of geometry in performative art and theatre, in particular the Triadic Ballet.

Cast Nickel - Museum für Angewandte Kunst Köln - Cologne, Germany

Figura Astratta (Abstract Figure)

The tubular shapes of Abstract Figure resemble the standing human form with arms outstretched. The streamlined body can be seen as that of the New Man, a fantasy figure in post-war Germany who was thoroughly modern and forward-thinking. The use of bronze and nickel reflect these notions and give the work a machine-like aesthetic, an idea that was explored by staff and students at the Bauhaus, where Schlemmer was teaching at this time. The inter-disciplinary environment of the school meant Schlemmer could easily access the resources and materials of the metal workshop to create this piece.

Abstract Figure was one of Schlemmer's first forays into expressing the human figure in three-dimensions. Following the First World War, Schlemmer increasingly placed an emphasis on the more spatial aspects of his art and how the dynamism of the human body could be displayed through sculpture and theater. Of such experiments, the artist wrote: "Sculpture is three-dimensional. It cannot be taken in at once, but rather in a temporal sequence of different locations and angles of view. As a sculpture is not exhausted by a single direction of view, the visitor is forced to move, and it is only the circumambulation and the sum of impressions that leads to the full experience of the sculpture".

Bronze and nickel - The Art Institute of Chicago

Triadisches Ballett (Triadic Ballet)

Schlemmer's ballet premiered at the Stuttgart Landestheater in September 1922, with music by the German composer Paul Hindemith. The production went on to tour throughout Europe in the 1920s, to cities including Weimar, Frankfurt, Berlin, and Paris, spreading the Bauhaus ideas of modern art. The ballet didn't have a plot, but rather three acts of different moods and color which Schlemmer described as a "party of form and color". Act One was yellow, Act Two, pink, and the final Act was black. It was performed by three dancers, two female and one male, who wore a total of 18 costumes. The costumes over-emphasized the forms of the human body, turning the dancers into geometrical constructions and they moved both with and against the wearers as they danced the ballet, restricting some movements and highlighting others. The mixed media of their construction variously reflected and absorbed light further emphasizing certain body parts and structural elements.

Schlemmer was not the first to explore the traditional dance form of ballet in a modern way. At this time, the Ballets Russes, founded by the Russian art patron Sergei Diaghilev, was at the height of its popularity. Diaghilev commissioned new music from the composers Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev, accompanying by sets designed by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Schlemmer's Bauhaus colleague Wassily Kandinsky. In the Triadic Ballet, however, Schlemmer was the first artist to fuse dance and modernism through his exploration of abstraction in real space. It also marked a breakaway from classical ballet's focus on the soloist and the duet, instead emphasising a collective approach to dance. Schlemmer described his attempts to explore the relationship between body, shape, color and space as "artistic metaphysical mathematics". As well as the physical movement of the dance, the costumes can be seen as a living embodiment of Schlemmer's previous sculptural and pictorial work. The performers appear machine-like in their faceless costumes, reflecting on the zeitgeist of the New Man.

Photograph of seven of the original Triadic Ballet costumes. Costumes are mixed media, predominantly metal and fabric.

Grotesk I (Grotesque I)

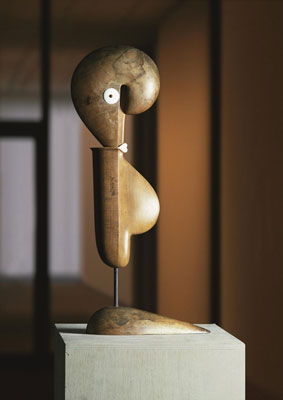

Schlemmer's Grotesk I shows a greater level of abstraction than most of his other work. Indeed, it is only discernible as human by the inclusion of the large ivory eye and mouth. Designed by Schlemmer and carved from walnut by Josef Hartwig, the Technical Master of the stone-sculpture and wood-carving workshops at the Bauhaus, the process of its creation demonstrates the collaborative working practices at the school. The sculpture takes the form of sweeping curves in a large S-shape, delineating the upper and lower body.

The piece can be seen as an exploration of the materials from which it is composed, contrasting the figure's curved shape with the firmness and solidity of the wood and the patterned grain of the polished surface. Built onto a metal pole which acts as a spine, the figure can swivel, changing the relationship between the body and its foot-like base. This ability to see the sculpture from a range of angles, allows the viewer to consider the human figure and its relationship to its environment in a fluid and dynamic way.

The title also sets it apart from his other work in that it directly references its quasi-human qualities. Schlemmer mixes natural materials with exaggerated forms to create a sculpture that is both attractive and repellent, depending on how the shapes are interpreted. The piece may have been a response to an exchange between Schlemmer and Swiss artist, Otto Meyer-Amden. Meyer-Amden suggested that Schlemmer's biggest talent was in the production of grotesque imagery, an accusation that Schlemmer rebutted, stating that: "I always defended myself against the grotesque. I wanted to be at the edge but still avoid making the sublime ridiculous". This figure was first exhibited a few weeks after this discussion.

Walnut, ivory, and metal - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Konzentrische Gruppe (Concentric Group)

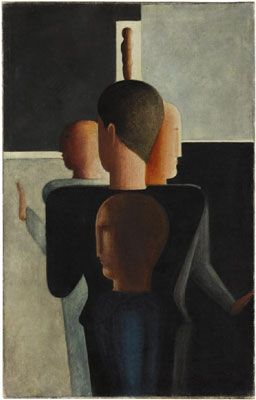

Based on a sketch from 1921, here Schlemmer depicts several figures looking in all directions, yet consciously ensures that all of them avoid the gaze of the viewer. These non-gendered faces are a common theme in the artist's work, presenting humans as statue-like, mechanical creatures. The background creates an abstract pictorial area through four rectangular planes of sombre hues. This marks an unusual departure from the colorful geometry of many of the paintings and designs of the Bauhaus.

The image is a study of multiple forms and their relationship to each other, focusing on the spatial positioning of the figures. The outstretched hands of two of the middle figures suggest they are exploring the undiscovered space of the painting, whilst the white gap at the top of the canvas features a small silhouette of a figure, hinting at an open doorway, or that the space has further unknown depths. The bodies and limbs of the figures seem to radiate out from the bald-headed figure in the near-middle of the canvas, giving the work its title. The physical similarities between this figure and Schlemmer possibly suggest that the artist has portrayed himself at the center of his own work, the point around which the other figures gravitate. The piece was created as part of a group of works in 1925, when Schlemmer was at the height of his career at the Bauhaus. All of them sold quickly to private collectors and museums, helping to make his name internationally. This led to Schlemmer nicknaming them the "gallery pictures". This was one of Schlemmer's works that was designated as 'degenerate' by the Nazis.

Oil on canvas - Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Bauhaustreppe (Bauhaus Stairway)

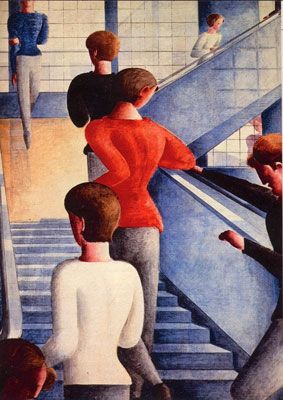

Unlike the imaginary architectural spaces of his other paintings, in Bauhaustreppe Schlemmer depicts a real place: the staircase in Walter Gropius's Bauhaus building in Dessau. Based on a photograph taken in 1927 by T. Lux Feininger of students leaving a class, Schlemmer uses the geometrical construction of the staircase like a stage, positioning figures in a carefully choreographed scene. The grid structure of the windows is continued throughout the picture, bringing into play a mathematical element seen in other works by the artist. The use of bold primary colors paired with the strong geometry closely ties the piece to the wider Bauhaus style.

Schlemmer painted this work three years after leaving the Bauhaus and it can be seen as both a farewell to the school and a protest piece against the forced closure of its Dessau site, which was announced in July 1932. He described the painting in a letter as his "best work", and it was to be the last major painting of his career. Schlemmer was not the only artist to tackle this topic, Yamawaki's collage, The End of the Dessau Bauhaus (1932) depicts a uniformed Nazi and a politician marching across the Bauhaus buildings. Schlemmer's work is less overtly political, however, and instead presents the schools as a lost utopia of purpose and learning filled with ordinary students, their contemporary clothing and haircuts grounding them in the present. The painting became a symbol of the impact of the Nazis on art and the image's iconic status was affirmed when Roy Lichtenstein produced his own homage to the work in 1989.

Despite the use of a non-imagined location, Schlemmer is still able to experiment with the movement of bodies in space with the unlikely perspectives and inclusion of the mysteriously floating figure at the top of the stairs. This en pointe ballet dancer challenges the viewer whilst introducing a dance element, reflecting Schlemmer's love of theatricality and movement. The descending dancer may also represent the hope that the difficult political period would come to an end and that the school and its activities would find a way to persist, an almost angelic presence amongst the more mundane daily activities of the other figures. The people in the picture are similar to those seen throughout the artist's career - modular and faceless.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Biography of Oskar Schlemmer

Childhood

Oskar Schlemmer was born in the south-westerly region of Swabia, Germany to Carl Leonhard Schlemmer and Mina Neuhaus; he was the youngest of six children. Following the death of both of his parents around 1900, when he was 12, Oskar was raised by his sisters.

Early Training and Work

Schlemmer quickly learnt to become independent and this is seen in his enrolment as an apprentice, at the age of 15, in an inlay workshop, before moving on to an apprenticeship in a marquetry workshop in 1905. During this time, Schlemmer also continued his studies, firstly as a pupil at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Stuttgart, before winning a scholarship to the city's Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Art). Here, under the guidance of his teachers Friedrich von Keller and Christian Landenberger, Schlemmer went into the countryside and painted directly onto canvases, in the en plein air approach of earlier avant-gardes.

Schlemmer's landscapes became increasingly geometric, particularly following his discovery of the work of Paul Cézanne. After a brief stint in Berlin in 1911, Schlemmer moved back to Stuttgart, where he became master student of the abstract artist, Adolf Hözel. Schlemmer continued to explore the relationship between form and color, and moved more towards Cubism.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Schlemmer enlisted for military service. Following injury, he was moved to a position with the military cartography unit in Colmar, where he remained until 1918. The doll-like figures he created in this period may have been a reaction to the wounded soldiers he saw in military hospitals during the war.

Mature Period

Following the war, Schlemmer began to work in sculpture, seeing it as a logical progression for his geometric art to become three-dimensional. He also recognized performing arts as an underdeveloped medium which offered new outlets for expression. Returning to the Bildenden Künste in Stuttgart, Schlemmer, alongside the artist Paul Klee, worked to bring these new ideas to the next generation of artists by updating the curriculum. These efforts to reform arts education were recognized by Walter Gropius, the director of the Bauhaus, who invited Schlemmer to run the wall painting and sculpture departments at his school. In 1920, the newly-married Schlemmer and his wife Helena Tutein (known as Tut) moved to Weimar to begin his teaching career.

In the summer of 1921, shortly after Schlemmer's arrival, the Bauhaus theater workshop was founded. It was initially overseen by the German artist Lothar Schreyer, but two years later Schlemmer was appointed to the position, replacing Schreyer as the department's Master of Form. The Bauhaus marked the most productive period of Schlemmer's career. The school's environment of collaboration encouraged Schlemmer to think in more spatial terms and to experiment with different materials. He worked and shared ideas with Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Johannes Itten, embracing Gropius's ethos of collective working and the idea of multiple art disciplines and life coming together as a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk).

In 1925 the Bauhaus published some of Schlemmer's theoretical ideas in an essay entitled Mensch und Kunstfigur (Man and Art Figure). In this text, Schlemmer wrote of his experiments in painting, sculpture, and stage work, citing the human figure as linking the worlds of two-dimensional pictorial art and the three-dimensional stage. Although attracting international attention with the paintings he had produced during his time in Weimar, after the Bauhaus moved location to Dessau in 1925, he decided to focus his attentions on his stage work.

During their time at the Bauhaus, Oskar and Tut also engaged fully in the life of the school, socializing with other staff members including Gunta Stolzl, Marcel Breuer, Josef Albers, and Marianne Brandt and, in 1926, Schlemmer was tasked with organizing the first Bauhaus party, The White Party. Schlemmer retained responsibility for a number of the famous parties that followed including the Beard-Nose-Heart party (1928) and The Metal Party (1929). The couple had their three children during this period, Karin (1921), Ute Jaina (1922), and Tilman (1925).

Schlemmer resigned his Bauhaus position in 1929, due, in part, to the increasingly uncomfortable political atmosphere in Germany, and in part to Gropius's departure as director and the appointment of the architect Hannes Meyer as his replacement. In October 1929, the Bauhaus published a special edition of its magazine, dedicated to Schlemmer to honor his departure. Years later, Gropius described Schlemmer as a Master who had "played a unique role in the Bauhaus community".

Late Period

In June 1929, Schlemmer accepted a position as a teacher at the Staatliche Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe (State Academy of Fine and Decorative Arts) in Breslau. After his experimental years at the Bauhaus, he returned solely to painting, and continued to explore geometric constructions and color on canvas. Schlemmer was forced to leave Breslau in November 1932 when the Staatliche Akademie closed following the Wall Street Crash and the ensuing financial crisis. He quickly found another professorship, this time at the Vereinigte Staatsschulen für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe (United State School for Fine and Applied Art) in Berlin.

His tenure, however, did not last long. With the rise of the Nazi party in the early 1930s, Schlemmer and other avant-garde artists were pushed out of their teaching roles and following Nazi election success in September 1930, it was ordered that Schlemmer's murals at the Weimar Bauhaus be painted over. Whilst many other artists left Germany, Schlemmer stayed but moved to rural south Baden. Feeling ostracized, he created no artwork from 1933-1935. His melancholy mood was only intensified by the inclusion of his work in the Nazi-organized 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. Despite this, his works were exhibited in major exhibitions in London and New York in 1938. He began to paint again, but his work took on a more sombre style as he began to process his new situation through his art.

Towards the end of his life, Schlemmer began to work in the Institut für Malstoffe (Institute for Painting Materials) in Wuppertal, alongside artist friends including the German painter Willi Baumeister, and Georg Muche, another Bauhaus Master. This was a lacquer factory, and the opportunity meant Schlemmer could continue to experiment with art and new materials including compositions in lacquer paint and on panels of wood, cardboard, and steel. In October 1941, he attempted to arrange a public exhibition of these works, but it proved too difficult to realize. Schlemmer died two years later from a heart attack in Baden-Baden.

The Legacy of Oskar Schlemmer

During his lifetime, Schlemmer's work was exhibited widely and achieved acclaim both in Germany and abroad. He was regarded as an inspiring teacher of avant-garde art and a pioneer in many fields, including painting, sculpture, and theater. He is best known for his works investigating movement, form, geometry, and rhythm, most prominently his Triadic Ballet (Triadisches Ballett) which toured extensively during the early-to-mid 1920s and is seen as a forerunner of contemporary choreography. Although the original choreography of the ballet was later lost, it was reconstructed by Ulrike Dietrich and Gerhard Bonheur in 1977 and has been performed a number of times since, most recently in Munich in 2014. Furthermore, his close professional relationships and friendships with other artists of the era have helped to shed light on the activities of the Bauhaus, for example his letters to Willi Baumeister reveal how staff and students reacted to changes at the institution.

In the years after his death, there were memorial exhibitions held in Berlin, Munich, Stuttgart, and Frankfurt. This was followed by a large-scale exhibition at the Württenbergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart to mark the ten-year anniversary of his death. Schlemmer's wife, Tut, ensured that his literary estate went to the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, where it joined the largest collection of his artworks to create the Archiv Oskar Schlemmer. More recently, Schlemmer's use of dance and design has influenced popular culture, including the music videos of New Order, Lady Gaga, and David Bowie and the fashion designs of Hussein Chalayan and Alexander McQueen. Schlemmer has also been a key influence on contemporary designers particularly Eric Roinestad, whose ceramic work directly references Schlemmer's costume designs.

Influences and Connections

-

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne - Christian Landenberger

- Friedrich von Keller

- Adolf Hölzel

-

![Walter Gropius]() Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius - Lothar Schreyer

-

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism ![Geometric Abstraction]() Geometric Abstraction

Geometric Abstraction

Useful Resources on Oskar Schlemmer

- Oskar Schlemmer: Visions of a New WorldOur PickBy Ina Conzen

- The Letters and Diaries of Oskar SchlemmerOur PickSelected and edited by Tut Schlemmer, translated by Krishna Winston

- Beyond the Bauhaus: Cultural Modernity in Breslau, 1918-33By Deborah Ascher Barnstone

- The Theater of the Bauhaus: The Modern and Postmodern Stage of Oskar SchlemmerBy Melissa Trimingham

- Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity, 1919 - 1933By Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman

- Human-Space-Machine: Space Experiments at the BauhausBy Torsten Blume, Christian Hiller, and Stephan Müller

- Man: Teaching Notes from the BauhausBy Oskar Schlemmer

- Dance the BauhausBy Torsten Blume

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI