Summary of Maya Deren

At a time when American filmmaking fell into the category of either classical Hollywood or realist documentary, Maya Deren conceived of a third, poetic, alternative. Even though she only completed six short films (a seventh was produced posthumously), Deren's lyrical psychodramas established her in American avant-garde cinema. Deren's films allude to the "dream logic" explored by the European Surrealists, but her unique vision would evolve to embrace the expressive qualities of dance and the mystical themes of Haitian ritual. One of the few women working within the avant-garde, Deren's life was cut short at the age of 44. But by then she had produced a body of work, including theoretical writings and a sizable cache of unedited footage, that would galvanize future generations of independent filmmakers. Deren's drive to produce, promote and distribute her films, moreover, set a working pattern that gave impetus to the formation of new independent film coops.

Accomplishments

- Deren's first film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), is the most highly regarded of all her films. Her conceptual approach, which saw Deren ignore conventions of continuous storytelling and third person objectivity in favor of obscure juxtapositions and uncanny doublings, captured the inner realities and emotional experiences of her protagonist. Meshes of the Afternoon remains a point of reference for avant-garde filmmakers to this day.

- While she is seen by many as the heir of Surrealist filmmakers like Buñuel, Dalí, and Cocteau (a lineage she did not recognize), Deren's film were more personal and idiosyncratic in their focus on ethnography and Haitian mythology. These ideas helped Deren realize the lyrical potential for film and dance, and to explore the place of individuals in relation to society (Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946)), and indeed, the whole cosmos (The Very Eye of Night (1952-55)).

- Deren suggested her films could be defined by what she termed their "vertical plunge" (a direct challenge to the linear continuity style preferred by commercial filmmakers). For Deren, a vertical plunge gave rise to a multifaceted film style in which meanings were generated through sudden shifts in time, mood, tone, and rhythm. She achieved this goal through the repetition of images, symbols, and sounds, and through various methods of image distortion (such as slow motion and negative projection).

- Deren had conceived of an experimental American film culture that functioned as an antidote to the commercial Hollywood film. She assumed total control of her films - from pre/production, to promotion, to distribution - and in so doing, established a working model for future independent film production. Contemporary avant-garde filmmakers and video artists who tour, lecture, and distribute their own work, and who part/finance their work through awards and grants, are heirs to Deren's example.

The Life of Maya Deren

Scholar Brittany Shaw writes, "In filmmaking, Deren found a refuge where at last ideas did not need to be translated through clumsy words: the images in her mind could become images on screen. To her, film was more akin to dance or music than a piece of literature or a photograph".

Important Art by Maya Deren

Meshes of the Afternoon

Meshes of the Afternoon is a landmark work in the history of avant-garde cinema. Written by Deren, and co-directed with her husband, Alexander Hammid, the narrative follows a woman (Deren) who, upon falling asleep, dreams of chasing a mysterious hooded figure with a mirror for a face. The pursuit leads her through a series of repetitive and disorienting sequences within her house, where she encounters various everyday household objects, such as a bread knife, a telephone, and a phonograph. These objects, seemingly ordinary, take on a menacing and enigmatic quality within the dreamscape, contributing to the film's atmosphere of uncanny unease. The woman's repeated re-entry into the house and the persistence of motifs, like a flower on the driveway and a falling key, create a circuitous narrative structure that underscores the themes of entrapment and the cyclical nature of the subconscious mind.

According to Deren, the film was "concerned with the inner realities of an individual and the way in which the subconscious will develop, interpret and elaborate an apparently simple and casual occurrence into a critical emotional experience". Made with a budget of around only $275, and featuring non-linear editing, oblique camera angles, and slow motion, the film remains Deren's most famous work, and a staple of American avant-garde cinema. Specific details surrounding the production of the film are sparse. It is known that Deren provided the poetic concepts while Hammid translated these ideas visually. Deren's initial concept was based on the idea of a subjective camera that would capture her point of view without using mirrors, moving through spaces as if through her own eyes.

Originally produced without a score, Deren's third husband, Teiji Ito (who had travelled with her to Haiti) later composed a highly percussive musical accompaniment, a haunting piece that enhances the film's anxious, dreamlike atmosphere. Ian Christie of the British Film Institute writes, "Meshes has been invoked as seminal by many traditions over eight decades. For years, this 14-minute film was claimed as a founding inspiration of a distinctively American form of highly personal poetic psychodrama, typified by Stan Brakhage, who hailed Deren as 'the mother of us all'".

16mm film

The Witch's Cradle

The Witch's Cradle (aka Witches' Cradle) is an unfinished, silent, experimental short film written and directed by Deren, featuring Marcel Duchamp, and filmed in Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery. The Surrealist film showcases repetitive imagery involving a string fashioned into a bizarre, spiderweb-like pattern over the hands of several individuals, notably an unnamed young woman (Pajorita Marta) and an elderly gentleman (Duchamp). Despite having a shooting script, many of the shots in the film were improvised and not clearly defined in terms of meaning or action. The Witch's Cradle includes shadowy darkness, people filmed at odd angles, an exposed human heart, and other occult symbols and ritualistic imagery. In his book Film as a Subversive Art, curator Amos Vogel wrote, "Her collaboration with Duchamp in this film exemplifies the fusion of artistic mediums, pushing the boundaries of what film could represent".

Duchamp played a crucial role in the production. After moving to New York from Paris, Duchamp had assisted Peggy Guggenheim in organizing her new gallery space (where the film was shot). Deren drew inspiration from a number of Duchamp artworks that were displayed in the gallery. These included his Boîte-en-valise (a leather valise containing miniature replicas, photographs, color reproductions of works by Duchamp, and one original drawing); his First Papers of Surrealism (also known as Sixteen Miles of String or His Twine, Duchamp's installation was intended to introduce American audiences to Surrealism); and Duchamp's own 1926 film, Anémic Cinéma, featuring rotating cardboard disks. The film was conceived of as a comparison between the Surrealists' distortion of time and space and that of medieval magicians and witches. Deren worked on the film between August and September 1943, but after principal photography began, she abandoned the project. Some of the film's outtakes were found and stored at the Anthology Film Archives, while several sequences appear to be lost. The surviving shots are mostly semi-edited sequences, including one that Deren engineered to be played backward during post-production.

16mm film

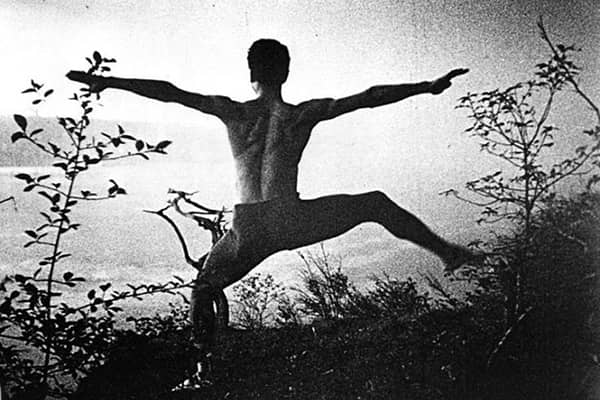

A Study in Choreography for Camera

A Study in Choreography for Camera is an experimental short that redefined the boundaries of dance and film. Filmed with a Bolex camera using 16mm filmstock, it features the dancer Talley Beatty. Film historian, Paula Marvelly calls it "Deren's concise masterpiece, which meanders between a silver birch forest, the interior of a plush apartment and the Egyptian Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art," and "the ultimate expression of the liberation of the dancer from the boundaries of the theatrical stage". The film opens with the camera rotating over 360 degrees, tracking Beatty's motions. As Beatty spins, he appears to have more than one face, forming an illusion of a totem pole. Deren also allows the camera to move independently of the dancer's movements, creating a floating, ethereal, visual experience. Despite its abrupt edits, juxtaposing different angles and compositions, and slow-motion sections, Deren captures the spontaneity and fluidity of Beatty's leap. She said of the film, "The movement of the dancer creates a geography that never was. With a turn of the foot, [Beatty] makes neighbors of distant places [it is] an effort to isolate and celebrate the principle of the power of movement".

Deren's ability to use film to liberate the human body from a single space (such as a stage or similar dancefloor space) gave rise to the term, coined by the New York Times dance critic, John Martin, "choreocinema". MoMA's Steve Higgins writes that Beatty "moves effortlessly within and between different environments (forest, living room, museum gallery, etc.), an achievement arrived at through the careful matching of his precisely choreographed movements with the film's editing pattern. [...] Beatty's disciplined performance never betrays the difficulties that he and his director must have overcome to attain so fluid a result. Deren's camera, in effect, becomes Beatty's partner". Marvelly concludes that as Beatty moves "effortlessly and gracefully through each of the threefold backdrops, limbs undulating and spinning, he finally comes to rest after an extended grand jeté with the serenity of a bodhisattva [a term from Mahayana Buddhism to describe an individual who is able to reach nirvana but delays doing so out of an act of compassion for suffering beings] gazing out into the never-ending distance. It is an arresting image to finale a hypnotic film, one which can be viewed as an analogy for spiritual transcendence of the manifest world through the dignity of the human form".

16mm Film - MoMA, New York (Film Department)

Ritual in Transfigured Time

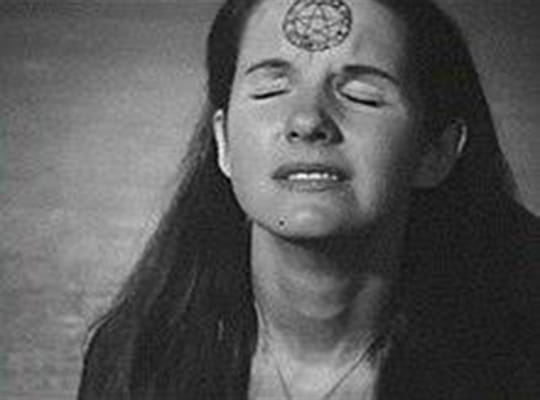

Ritual in Transfigured Time is an exploration of societal norms and metamorphosis through the power of ritual. The 15-minute film short begins in a domestic setting, moves to a party scene, and ends with modern dance performed in an outdoor setting. The film's continuity is established by an emphasis on gesture and/or dance. The Trinidad-born American actor and dancer, Rita Christiani, arrives at an apartment where she encounters Deren engaged in a "cat's-cradle" weaving ritual. A strange wind engulfs the entrance and Christiani becomes transformed by the looming ritual and the ritual of the social gathering. Christiani's character navigates a room full of people through expressive movements, moving to an exterior setting that culminates in a chase-cum-dance with actor Frank Westbrook (credited simply as "dancer").

The four protagonists - Christiani, Westbrook, Deren, and the famous erotic diarist and essayist, Anaïs Nin - embody different social roles. Christiani plays a young woman introduced to society, overseen by Nin's disapproving older woman, and Deren's more animated character. Initially an outsider, Christiani integrates with the guests through her mesmerizing dance, crafted through Deren's meticulous editing. Deren choreographed the scene, emphasizing the flow of interactions, stating that her aim was to fuse "all individual elements into a transcendent tribal power toward the achievement of some extraordinary grace". The film links Deren's weaving ritual with the ritual of social gatherings. With Christiani moving through the party, meeting guests with increasingly expressive and fluid movements, she successfully transforms the gathering into a dance performance (with Westbrook) that highlights themes of fear of rejection and the freedom of expression in surrendering to ritual. The film ends with Deren's character running into the ocean, with the film switching to a negative image, symbolizing, perhaps, the idea of death and rebirth.

16mm Film

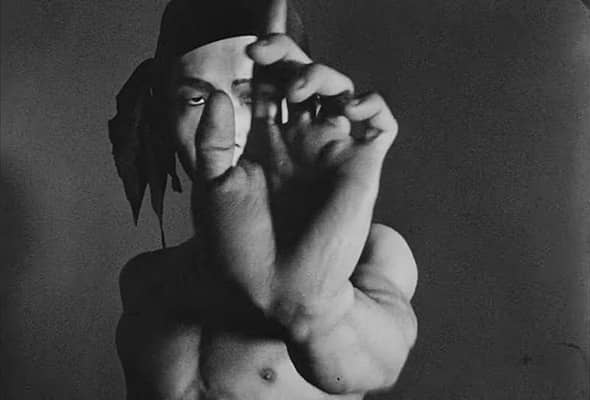

Meditation on Violence

Meditation on Violence explores the fluidity and discipline of traditional Chinese martial arts through the precise movements of performer Chao Li Chi. Unlike Deren's earlier, more dynamic style, Meditation on Violence presents a more restrained approach, blurring the line between violence and balletic beauty. The use of shadows enhances the choreography of WuTang and Shaolin rituals (with their emphasis on mind/body control), emphasizing the cultural and spiritual dimensions of these practices. Deren sought to portray violence, not as a destructive force, but rather as an art form deeply rooted in cultural and spiritual practice. By focusing on the discipline and form of the practice, she wanted to challenge Western perceptions of violence and to highlight its more contemplative nature in Eastern philosophies. This thematic exploration encourages viewers to reconsider their understanding of violence through aesthetic and philosophical dimensions.

According to avant-garde filmmaker, Stan Brakhage, Meditation on Violence is Deren's most personal film. Although she doesn't appear on screen, Brakhage observes that "she is the camera, she's moving, she's breathing in relation to this dancer". Deren experiments with time by reversing part of the footage, creating a Mobius strip effect (where the viewer cannot distinguish between clockwise or counter-clockwise) that makes the movements appear almost identical whether viewed forwards or backwards. By isolating parts of the body, moreover, Deren crafts a surreal visual experience. Filmed both indoors and outdoors, the edited reversal of movements results in a formless shape that Deren called the "ultimate form". This 15-minute film continued her exploration of the interplay between the filmmaker and pure movement, showcasing a balance of motion moving in counter directions.

16mm Film

The Very Eye of Night

With The Very Eye of Night, Deren collaborated with esteemed choreographer Antony Tudor and his troupe of ballet dancers from the Metropolitan Opera. For Deren, the project was both a scientific and astrological venture centered on a stunning abstract ballet performance that explores themes of dream states, cosmic order, and the mystical relationship between the human body and its place within the infinite expanses of the universe (the micro and the macro, in other words). In the 15-minute film, Deren utilizes negative imagery, where white figures move against a dark background, creating a striking and otherworldly visual experience. The choreography is studied and fluid, with dancers appearing to float through space, seemingly free from horizontal and vertical constraints as well as all gravitational forces. A "fourth dimensional" effect in created in the movement between the dancers and Deren's camera.

The Very Eye of Night was Deren's last completed film. She began filming in 1952 and premiered it in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1955. However, it wasn't screened in New York until 1959 due to a financial dispute. In the later version, Deren's husband Teiji Ito contributed a soundtrack with tone blocks and bells, evoking the trance rhythm similar to that in Meshes of the Afternoon. Inspired by her experiences in Haiti, and her interest in Haitian Vodou, Deren wanted to depict a vision of dance that transcends earthly limitations. The film aims to evoke a sense of spiritual exploration, portraying dancers as celestial beings navigating the vastness of the night sky. Through this work, Deren conveys the idea that dance is not only a physical expression, but also a metaphysical journey. The film's exploration of cosmic themes, its use of experimental cinematic techniques, and its thematic depth, marked the film as a fitting finale to Deren's short life.

16mm film

Biography of Maya Deren

Childhood

Maya Deren was born to Jewish parents, Solomon Derenkowsky and Gitel-Malka (Marie) Fiedler, in Kyiv, Ukraine. Marie was an economist and musician, while Solomon was a doctor who had trained at the prestigious Psychoneurological Institute in St. Petersburg. Maya was originally named Eleanora, after the popular Italian actress, Eleonora Duse. Between 1917 and 1921 a military struggle for control of Ukraine was waged between Ukrainian independent forces and pro-Bolshevik agitators who were seeking to establish Soviet rule over a country that had only just won its independence from the Russian Empire (the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) having been formally established in November 1917).

Many civilians of different nationalities were victims of a war that saw over 1,000 anti-Jewish riots and barbaric military actions - or pogroms - specifically targeting Jews. In fear for their safety, the Derenkowskys managed to flee to America. They arrived in New York, joining family members in Syracuse in 1922. Solomon studied at Syracuse University where he gained his American degree in medicine. Once qualified as a psychiatrist, he was appointed assistant physician at the Syracuse State School for Mental Defectives. In 1928, the Derenkowskys gained American citizenship and shortened the family name to Deren. The Deren family dynamic was not good, however, and Solomon and Marie frequently spent time apart.

Early Training and Work

Despite the upheavals in her young life, Deren demonstrated remarkable resilience and intelligence. She attended elementary and high school in Syracuse, before moving to Geneva in 1930 to study at the League of Nations' International School where she became known as a precocious student with a passion for poetry and photography. During her three years in Geneva, Marie moved to Paris so she could be closer to her daughter. Deren returned to Syracuse in 1933, enrolling at Syracuse University where she studied journalism and political science. There she met and married fellow student, Gregory Bardacke in 1935. The newlyweds moved to New York City where she and her husband, a union organizer, became heavily involved in the socialist movement. Historian Judith E. Doneson argues that "Many thought Deren's socialist leanings served as a replacement for Judaism. Her father, whom she adored, was agnostic. Clearly aware of her Jewish roots, she felt no affinity for her religion or culture. Though aware of problems for Jews in the world, Deren looked to socialism as the cure for such issues. Indeed, socialism allowed her to merge her Jewish identity into a universalist worldview".

Deren completed a Bachelor's degree in literature at New York University in 1936. In 1938, and recently divorced from Bardacke, she attended the New School for Social Research. She earned her master's degree in English literature from the all-women's Smith College, Massachusetts, in 1939, with a thesis on French Symbolist influences on Anglo-American poetry. Historian Greer Sinclair writes that, after graduating from Smiths, Deren "moved to Greenwich Village, where she lived in a green tree-lined nexus of like-minded revolutionary thinkers and artists. [...] One day she was an assistant to Max Eastman (a 'Village radical' and patron of the Harlem Renaissance), typing up his notes on communism and socialism, even as he moved from enthusiasm to critique. She then worked for William Seabrook, the notorious reporter and adventurer, most famous for his studies of occult 'witchcraft,' his studies of West Africa, and his account that he had engaged in ritualistic cannibalism. These influences coalesced in Deren during these Village days and nights, and in the fertile realm of her imagination she created the artist she would soon become".

In 1940 Deren met the dancer Katherine Dunham. In his article for The New Yorker, Richard Brody writes, "[Deren] became fixated on [Dunham] the founder of a dance company, and an academically trained anthropologist. Deren [was] already deeply devoted to the art of dance, even though she had no training, and she more or less imposed herself on Dunham as a secretary and assistant". During 1941 and 1942, Deren toured America with Dunham's dance troupe. Dunham later offered a candid insight into Deren's character, stating: "She felt that she was physically irresistible. She would work like a bee to get noticed, shaking around, carrying on. She went after anybody including someone who belonged to someone else. She worked at it. I think sex was her great ace. I liked her curiosity, her vivaciousness. She was alive. I liked her bohemianism - she had no hours. Any hours were all right, just like mine". While on tour, Deren gave an indication of her future artistic direction when she published an article entitled, "Religious Possession in Dancing", for the journal, Educational Dance.

In 1942 Deren moved to Los Angeles to work as Dunham's publicist. It was in LA that she met photographer and filmmaker, Alexander Hackenschmied. He had fled his native Czechoslovakia shortly before the Nazi invasion. Historian Mark Alice Durant writes, "An accomplished photographer and cinematographer, Hammid had a sophisticated and adventurous visual sensibility, developed while making both experimental and documentary films in pre-war Czechoslovakia. Film stocks and cameras, light and shadow, frozen moments and moving images, the very materiality of photography and cinema were the dowry of their union, and provided the essence of Deren's new identity". Having changed his name to Sasha Hammid, he and Deren were married later that year. Deren continued to publish some pieces of poetry and newspaper articles, but Hammid had introduced his wife to the poetic possibilities of filmmaking. She said later, "When I undertook cinema ... it was not like discovering a new medium so much as coming home into a world whose vocabulary, syntax, grammar, was my mother tongue; which I understood, and thought in, but, like a mute, had never spoken".

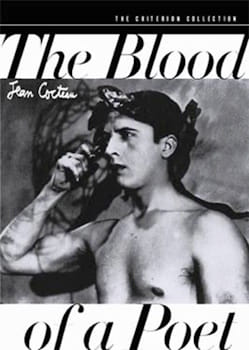

Having adopted Hammid's affectionate pet name for his new wife, "Maya" (the "mother of illusion" in Buddhism), the couple moved to the mountainous region of LA, Laurel Canyon, from where Deren continued her photographic work (which would include freelance assignments for Flair, Harper's Bazaar, and Architectural Forum magazines). In 1943 Deren was left a modest sum of money by her recently passed father. She used the money to buy a 16mm Bolex camera and, on a meagre budget of $270, she and Hammid (who borrowed lighting equipment from his production studio) made Meshes of the Afternoon. Filmed in their home, the 14-minute surrealistic film would establish Deren as a true pioneer of American experimental cinema. Ian Christie of the British Film Institute writes, "Deren would indignantly reject suggestions of influence from two earlier European avant-garde landmarks, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí's Un chien andalou (1928) and Jean Cocteau's The Blood of a Poet (Le Sang d'un poète, 1930). But for all its cool originality, the eerie game of repeated symbols that its maker-protagonists play out in their West Hollywood home and garden - with a flower, key and knife linking Deren's divided self and a sinister mirror-faced figure - has undoubtedly extended the legacy of those earlier works".

Mature Period

By 1944, Deren and Hammid had returned to New York, setting up home at 61 Morton Street in Greenwich Village (the apartment would remain Deren's New York home for the rest of her life). Deren, who earned a modest income from photographic portraiture for the likes of Vogue and Vanity Fair, continued to work on avant-garde films, taking inspiration from dance, ethnography and myth, the French symbolist school, and the modernist poetry of T. S. Eliot. In 1944 she made The Witch's Cradle, and unfinished work featuring Marcel Duchamp, that was filmed in Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery. She followed in 1945 with A Study in Choreography for Camera, her first to focus on ritualized dance.

In February 1946, Deren rented The Provincetown Playhouse, a West Village theatre, where she screened her films for a paying audience. Her eagerness to promote and distribute her own work set a new precedent for independent filmmakers. Among the Provincetown audience was a 24-year-old cineaste named Amos Vogel who said that Deren's films had alerted him to "a new kind of talent [and] an individual expressing a very deep inner need". The following year Vogel and his wife, Marcia, had founded a film society called Cinema 16 in the same venue. Between 1947-1963 Cinema 16, which gave a platform to avant-garde and independent film production, became the largest cinema club in the U.S. (Vogel went on to found the New York Film Festival in 1963). Film scholar Bill Nichols writes, "Contemporary avant-garde filmmakers or video artists who describe and define their own work in written commentary, who tour, lecture, and self-distribute their work, and who support themselves with fees and grants follow in Deren's footsteps. [...] Along with the inexhaustible efforts [of Vogel], Deren formulated the terms and conditions of an independent cinema that remain with us today".

Also in 1946, Deren became the first filmmaker to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship grant. The following year, and recently divorced from Hammid, Deren travelled to Haiti (likely inspired by Dunham who had conducted anthropological field work in Haiti during in the 1930s) on the back of the Guggenheim award. She remained in Haiti for eighteen months and became immersed in Vodou rhythms and rituals. ("Vodou" is the name given to a complex blend of African spiritual traditions with Catholicism, whereas the term "Voodoo", with which it is sometimes confused, is more readily associated with a religion with origins in New Orleans.) Deren, who visited the island three times between 1947 and 1954, shot thousands of feet of 16mm film, although she never produced a finished film. She did, however, place Vodou ceremony, and the intersection of dance, ritual, and spiritual possession, as central to her practice.

Deren was accompanied on the Haiti trip by a then 15-year-old Japanese-American runaway, Teiji Ito. The son of parents who were active in theater, dance, music, and film (they had arrived in America shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941), his eclectic interests ranged from Asian, African, and Caribbean music to jazz, blues, and flamenco. Deren struck up a close and loving relationship with Ito whom she would later marry. She remarked of their first meeting (by chance, on on a New York sidewalk): "I suddenly stopped in the middle of a sentence. Things went clickety-clack in my head and I said: 'You're the one!'". (Ito later added music scores for Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), and At Land (1944).)

Film scholar Brittany Shaw writes that once back in New York, Deren became "an unmissable icon of the postwar art scene, whose fondness for handmade folkloric skirts and peasant blouses recalled her Russian roots. She frequently hosted screenings of her films in her apartment, for which she charged entry - she lived in poverty but could be industrious when she needed to be. She hosted large parties, full of drumming, dancing [and] Haitian Vodou rituals. When she wasn't traveling with her films or giving lectures, she would write into the night: furious letters to fellow artists, arguing about the state of experimental film; magazine articles; a published chapbook titled An Anagram of Ideas; film ideas; program notes. [...] She shared the pleasures of micro-budget filmmaking, explaining there was no one to fire and no one to answer to".

Late Period

In 1953, Maya Deren spoke at a Cinema 16 symposium called Poetry and the Film. She proposed that film could be understood on a vertical or horizontal basis. Horizontal storylines (in film and literature) carry a linear, cause/effect, narrative. For Deren, poetic films should follow a vertical development - or what she called a "vertical plunge" - whereby multiple layers of meaning arise from shifts of time, mood, tone, and rhythm, and through the use of repetitive symbols, images, sounds, and image disorientation. Also in 1953, Deren published Divine Horseman: The Living Gods of Haiti. The book, which includes text, photographs, and illustrations, would become recognized as a primary source book on the culture and spirituality of Haitian Vodou.

Deren continued her work in experimental film, culminating with her final completed project, The Very Eye of Night (1955). Collaborating with choreographer Antony Tudor, who brought with him dancers from the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School, the film is distinguished by its abstract and astrological themes, and the film's projection in negative. Premiering in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1955, the film would be Deren's final love letter to Haitian culture.

Deren died in 1961 at the age of 44. The mysterious circumstances of her death have given rise to wild speculation. Avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage suggested, for instance, that Deren's death was a punishment for her involvement in Haitian Vodou rituals. This claim was strongly refuted by Martina Kudláček in her 2002 documentary, In the Mirror of Maya Deren, which attributes her death to a cerebral hemorrhage caused by malnutrition and her use of amphetamines and sleeping pills. After her death, Deren's ashes were scattered at Mount Fuji in Japan by her (Japanese) husband who thought it was the perfect spiritual resting place for such a creative soul. Much of the unedited footage Deren shot in Haiti finally appeared in a 1981 documentary, Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, made by Ito. In 1990 Meshes of the Afternoon was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress in recognition of the film's "cultural and historical significance".

The Legacy of Maya Deren

Deren's films were groundbreaking in the way they interwove dance, choreography, ethnography, and psychology. To this thematic mix she brought innovative shooting and editing techniques such as multiple exposures and superimposition to overturn conventional concepts of filmic time and space. As curator Sally Berger puts it, "Deren wanted to define film as an art form, to create an artist's cinema based on neither Hollywood entertainment nor documentary [but] rather, a kind of film concerned with (what Deren described as) the type of perception which characterizes all other art forms [and] devoted to the development of a formal idiom as independent of other art forms as they are of each other".

Deren also laid the foundations for the birth of The Filmmakers' Cooperative (aka The New American Cinema Group), a non-profit organization devoted to the collection, preservation, and distribution of experimental film and media art in New York City, which was founded in the early 1960s following a gathering of 23 independent filmmakers, including Jonas Mekas, Shirely Clarke, Stan Brakhage, and Jack Smith. Ian Christie of the British Film Institute adds that Deren can be credited with "rising interest in women's film after the 1970s [that] would focus attention on her aesthetic of 'vertical cinema', creating an emotional and intellectual density within rather than between images". In this respect, avant-garde filmmakers such as Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, and Su Friedrich have continued Deren's fine legacy. Deren's mission to win financial backing for experimental filmmakers was finally realized in 1986 when the American Film Institute established a grant - the Maya Deren Award - to give financial support the work of contemporary independent film and video makers.

Influences and Connections

-

![Marcel Duchamp]() Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp -

![André Breton]() André Breton

André Breton ![Henri Bergson]() Henri Bergson

Henri Bergson- Katherine Dunham

![Anais Nin]() Anais Nin

Anais Nin- Alexander Hammid

- Teiji Itō

- Hella Heyman

- Amos Vogel

-

![Avant-Garde Art]() Avant-Garde Art

Avant-Garde Art -

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism - Vodou

-

![Carolee Schneemann]() Carolee Schneemann

Carolee Schneemann - Barbara Hammer

- Su Friedrich

- Curtis Harrington

- Stan Brakhage

![Anais Nin]() Anais Nin

Anais Nin- Alexander Hammid

- Teiji Itō

- Hella Heyman

- Amos Vogel

-

![Avant-Garde Art]() Avant-Garde Art

Avant-Garde Art -

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism - New American Cinema

Useful Resources on Maya Deren

- Essential Deren: Collected Writings on FilmOur PickBy Maya Deren and Bruce R

- Maya Deren and the American Avant-GardeBy Bill Nichols

- Choreographed for CameraBy Mark Alice Durant

- Maya Deren and the American Avant-garde: Includes the Complete Text of "An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Forum, and Film"By Bill Nichols

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI