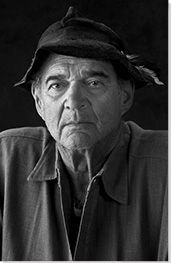

Summary of Larry Bell

"You need light to see, you need space to work," Larry Bell has wryly stated on more than one occasion when asked for his thoughts on the Light and Space movement with which the celebrated artist has been associated since its inception in the mid-1960s. More of a loosely affiliated group of artists than a cohesive movement, Light and Space is a distinctly Southern California style, concurrent with the Finish/Fetish trend, said to reflect the influence of the distinct light of the region and the inclination to use non-traditional, often industrial, materials to explore this phenomenon. For Bell, the singular concern with light, or rather the visual properties of light on a surface, remains a lifelong subject of exploration. His iconic glass cube sculptures, for which the artist is best known today, are mesmerizing examples of this investigation. The translucent cubes, at first stoic and austere, slowly reveal poignant experiences to the faithful viewer. The minimalist geometric sculptures offer a kinesthetic experience, as illusory shapes appear and evaporate within the cubic volume as one moves around the work.

Bell's desire to toy with the viewer's perception is a trait shared with other artists affiliated with Light and Space, most notably Robert Irwin and James Turrell. The legacy of Bell, however, is not only material but also conceptual. For the pursuit of industrial materials represented a rejection of art as an object, a dominant theoretical underpinning of Minimalism, in pursuit of art as experience. The use of glass, mirror, metallic films, paper and leftover scraps of Mylar were, for the artist, a means to an end, not the end itself. There were materials through which Bell interacted with his primary medium, light, and was able to transmit that experience to the viewer.

Accomplishments

- Larry Bell is among the first generation of artists to shape the contemporary avant-garde art scene in Los Angeles, the youngest artist to join the roster of the legendary Ferus Gallery with a solo exhibition in 1962. The gallery's artists were later bestowed the title of "The Cool School" in a 1964 essay by Philip Leider, critic and managing editor of Art Forum, who defined the group as having a "collective hatred of the superfluous" and concluded that "a construction of Larry Bell's, for example, cries 'Hand's off!' (This quality of distance, coldness, austerity has become the trademark of Ferus Gallery installations.)"

- Bell's cube sculptures exemplify the hard-edged appearance of Post-Painterly Abstraction and Minimalism, but create a markedly different experience. Instead of creating a distinctly defined, and inherently neutral object, Bell's glass sculptures appear ephemeral, constantly changing in response to their surroundings as well as the viewer's movement around the work. Therefore, the true subject is not the art object, per se, but the transformation of light in response to it.

- The artist is sometimes associated with a style of art known as Finish/Fetish. This movement, also known as the "LA Look," is characterized by immaculate surfaces, use of fabrication techniques, and use of new materials (industrial paints, resins, plastics) inspired by Southern California popular culture (i.e., cars, surf and sun) and the aerospace industry. Bell's use of metallic vacuum-coating technologies serves a prime example of this inclination.

Important Art by Larry Bell

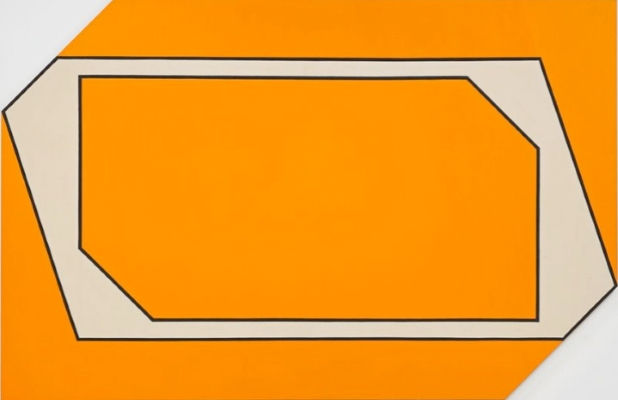

Lil' Orphan Annie

Lil' Orphan Annie exemplifies the post-expressionist stage of Larry Bell's development as a painter. Throughout these works, the young artist employed a minimal color palette with hard-edge geometric forms on shaped canvases. The large, flat areas of unmodulated color reinforce the flatness of the picture plane, while the inscribed geometric shapes, often set at a diagonal, create a sensation of depth. As Rachel Rivenc describes in her book, Made in Los Angeles (2016), Bell "depicted planes and actual shapes to suggest volumes nested one into the other and viewed in skewed perspective."

Bell is believed to be the first artist on the West Coast to exploit the use of shaped canvases, and shows a nearly simultaneous exploration of this format with renowned Minimalist painter Frank Stella's own experiments in this direction. Despite the similar strategy, there is a stark difference in the conceptual underpinnings taken by each artist. For New York-based Stella, the break with the traditional rectangle was a means to further emphasize the object-hood of the painting and flatness of the picture plane. For the West Coast artist, however, the objective was to create overlapping shapes that result in the illusion of depth on the flat surface, what the artist has described as variations of "cubic volume as dictated by the shape of the canvas."

The series of shaped canvases mark the final series of "pure" paintings by the artist. Another work in the series, titled Little Blank Riding Hood, was similarly based on a six-sided polygon. Melissa Wortz describes, "Bell has explained that the inspiration for this particular painting came from a specific architectural element, the skylight of his Marine Street studio in Venice, although he has also said that recognizing the similarity of this approach to Ellsworth Kelly's paintings is part of what encouraged him to make a change."

Soon after, he began to push the notions of volume further by incorporating glass and mirror fragments onto the surface of the canvas, complicating the eye's ability to read the flatness of the picture plane. Both series suggest the continued influence of Irwin's theories of Perceptualism on Bell, a concept of art focused on exploring the variability of the viewer's perception and optical experience while engaging with the work of art.

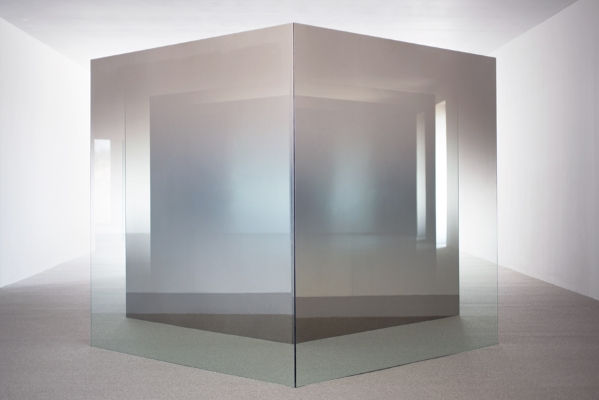

The Aquarium

Bell's earliest sculptural works echo the shaped paintings. The front and the back were cube-like shapes with opposite corners cut at a 45-degree angle, similar to the canvases. Additionally, these works were not true cubes as the width was much thinner, about 1/4 of the square dimensions of the front and back. In a way, they exaggerate the proportions of the painted tesserae forms, removing them from the wall and placing them upon a pedestal. Like the paintings, The Aquarium both incorporates and departs from artistic convention. Bell follows tradition by placing the sculpture on a pedestal, while decidedly moving in a new direction with the incorporation of everyday materials and employing a modernist geometric aesthetic. Paradoxically, the sculptures were still utilizing the vocabulary the artist used in his paintings, a motif the artist would later describe as volumetric illustrations of volume.

Mirror, paint, glass and silver leaf

Untitled

The earliest cube sculptures Bell created were conceived in similar materials as the shaped boxes, primarily cut mirror and clear glass, edged in metal. These works were visually complex, with patterns such as diagonal ellipses, layering illusions of volume onto the sculptural form itself. In this example from the Norton Simon Museum of Art, an elegant ellipse is inscribed within a perfect circle on each pane of glass creating a nearly cosmological chart when the reflections begin to play on one another ."When I think of an ellipse shape, I think of the galaxy of Andromeda," Bell explains. "It pulls on us from a roughly 40-degree angle, and that's a 40-degree ellipse. It's a huge volume." Thus, what first appears as a simple geometric pattern may also be read as a distortion of scale and perspective. By inscribing the universal form within the panels of the cube, a form the artist describes as small and intimate, he inherently distorts scale as another means to disrupt the viewer's perception.

Adrian Kohn notes the difficulty in summarizing the visual experience of these works in his essay, 'Work and Words,' for the exhibition catalogue, Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface, "Real space vies with reflected space here; elsewhere the shapes' apparent withdrawal into the cube's interior amounts to pictorial space rivaling real; and finally, since the shiny glass surfaces consist of ellipses and other discrete shapes, reflected space clashes with pictorial. Needless to say, a cube's insides can appear startlingly disjointed." Just as the earlier paintings had both reinforced and disrupted the viewer's reception of the flat picture plane, these early experiments with volumetric sculptural works both satisfy and frustrate the viewer's ability to see into the space defined by the cube. Thus, Bell continues to explore the eye's ability to perceive space and volume through the use of reflected and ambient light.

Vacuum coated glass and chrome cube with spherical shapes on six sides, 12-1/4 x 12-1/4 x 12-1/4 in - Norton Simon Museum, Museum Purchase with funds donated by the members of the 1967-68 Blum/Coplans Class, Pasadena Art Museum

Untitled

There is a quiet monumentality to Larry Bell's iconic glass cube sculptures. As solemn as the monoliths of Stonehenge and futuristic as the famous rectangular slab of Stanley Kubrik's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), an air of mystery beckons the viewer closer to the totemic works where the true aura of the sculpture can be appreciated. With each step, the appearance of the sculpture changes as light reflects both outward and through the interior of the cube. The viewer may find their reflection in the smoky glass from one angle, only to see their shadowy image dissolve upon taking another step. Set upon a pedestal of Plexiglas, the cubes almost appear to be floating, as light enters from all sides. The artist describes the interaction of light and surface as his true medium, and it seems the visceral engagement between the viewer and object is the true subject.

The industrial nature of Bell's materials and the geometric form of the cube seemingly align the artist with the Minimalist aesthetic, but the Los Angeles artist's interests were quite distinct from his New York peers. Where Minimalists explore issues of fabrication, repetition, and reinforce the notion of the object, Bell's works are handled directly by the artist, individually conceived, and ephemeral, due to microscopic variations in the metallic film altering the translucency and reflective quality of the glass. Where Minimalist objects were often set directly on the floor, Bell maintained the tradition of the pedestal, albeit his use of Plexiglas provides an innovative twist.

"The environmental space seen through and reflected by the glass, optically merges with the piece and becomes an intrinsic part of it," wrote art historian and curator Barbara Haskell for a 1972 solo exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum. "In addition to providing a vehicle for his color, glass in Bell's work serves as an agent for the dematerialization of the object." The results ranged from smoky charcoals to a subtle prism of reflected light. The artist used no pigments, any color seen on the cubes were the result of light passing through the metallic particles adhered to the surface of the glass.

The works bridge the Southern California Light and Space explorations with alternative materials and conceptual use of light as an artistic medium with the geometric precision and immaculate surfaces associated with the concurrent Finish/Fetish aesthetic, also dominant in the Los Angeles art scene. Moreover, there is a decidedly kinetic aspect to the sculptures, as the reflections, shadows, and shapes created continually morph as the viewer approaches and circumambulates around the work. As curator Michele D. De Angelus notes, "The qualities of the space in Bell's cubes, though visually perceived, are kinesthetically sensed. They are significant not only in their transportation of the realm of painterly concerns to three dimensions."

Courtesy the artist and Peter Blake Gallery - Glass and chrome-plated brass

6 x 6: An Improvisation

The series of Standing Wall installations created by Bell beginning in the late 1960s is a clear reflection of the modernist impulse for simplification. After the artist perfected his technique of assembling his glass cubes without the need of a metal frame he began to explore the light and prisms of color as they met and reflected at the corners, thus becoming a new point of interest for the artist to explore. It was no longer necessary to create the entire cube. Instead, the artist theorized that two panes of glass placed at a 90-degree angle could produce the desired affect. However, because his first vacuum-coating machine chamber could only treat 20-inch panels of glass, he began to construct these larger works with untreated pieces of glass. In order to increase the scale of his vision, for both his cubes and standing walls, Bell commissioned a new vacuum chamber that would allow him to coat glass panels up to six-by-ten feet. The new machine, completed in 1969, also allowed for greater control and flexibility to adjust the thickness of particles deposited on the glass surface.

The new works, collecting known as Standing Walls, provided an immersive experience. The new direction, consisting of a five-panel installation, made its debut in his 1972 solo retrospective exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum, curated by Barbara Haskell. Whereas the viewer would typically stand over the cube, the experience of viewing the standing walls is truly immersive. "There is no perceptual separation between the actual sheets of glass and their illusory reflections - both are perceived as equal physical realities," wrote Haskell. She continues, "Removal of the pedestal and metal edge eliminates any visual defining frame of reference and enhances the elusiveness of the space. The completely architectural scale of the walls contributes to transcending the 'object' by engaging the major portion of the viewer's field of vision."

In the 2014 installation at the Chinati Foundation, titled 6 x 6: An Improvisation, the artist brought together 32 new and previously treated glass panels to create a procession of 16 units joined at 90-degree angles, each panel measuring six-by-six feet. The surface of the glass panels varied from clear to light coatings of Inconel, a nickel-chromium alloy often used by the artist. The various treatments alter the way light passes through or reflects from the surface of the glass. As a result, walking around and through the installation becomes a game of cat-and-mouse with one's own reflection and visibility to others in the room. "He plays with light in such a wonderful way, that you have to think about what is now reality and what is the illusion of it," curator and director emeritus of the Chinati Foundation Marianne Stockebrand explained in a 2015 interview. "Your whole sense of the space is suddenly upside down, or back-and-forward. And the glass is the vehicle that makes that happen." The emphasis on disorienting the viewer's perception through a controlled manipulation of light and reflection is a defining characteristic of the Light and Space movement.

Clear and metalized glass, 16 pairs of 6-foot square glass panels joined at right angles

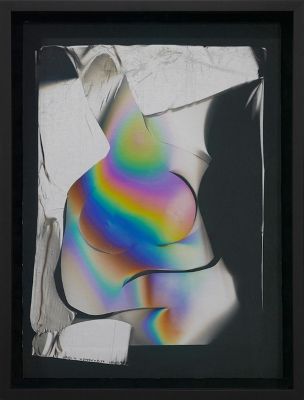

SF 6.20 11A (Small Figure)

In 1978, Bell started to experiment with coating paper with the same metallic deposits he had previously used on glass. Initially discovered by accident, he went on to produce multiple series, the earliest known as Vapor Drawings, incorporating the same geometric vocabulary found in his early cube sculptures. Because the paper absorbed and reflected light when combined with the metallic film, it created a prismatic effect in a gradient across the surface.

Whereas the cube sculptures grew increasingly refined over time, the works on paper became progressively complex. Deceptively simple, these works at first appear to be dimensional; they are perfectly flat while also incorporating numerous sheets of paper. In a multi-step process, Bell first masks the paper with strips of Mylar leaving areas exposed in the vacuum chamber. After processing, multiple sheets of cut paper are put together with a laminating process and sealed onto canvas for additional support. In the later Mirage and Small Figure series, the knife replaces the brush as the artist cuts into the paper with long sweeping gestures, creating abstract shapes inspired by the sensual form of a female torso or the curved body of an acoustic guitar, the latter inspired by his vast collection of 12-strings. The layering of shapes and nuanced gradients create, in much the same way as his early geometric paintings, a push-and-pull illusion of depth and volume on the flat picture plane.

Mixed Media on Black Arches Paper

L.K.L. 4/15/13

Lyrical and evanescent, Larry Bell's Light Knots represent the culmination of the artist's previous experience with materials and technology. Like glass, the translucent Mylar of the Knots transmit, reflect, and absorb light, continuing the artist's lifelong investigation with the subject. Similar to the Vapor Drawings, the hanging sculptures are built from materials the artist had previously used to process his other work. "I had been making these components for the collages for years, but it never occurred to me that they had more potential than just what I was using them for," he described in a 2015 studio visit, "All of a sudden, the work presented another aspect of itself... and it was a redemption of all things new again."

Each of the hanging sculptures are unique, made from a single sheet of Mylar film, which the artist improvisationally cuts, then folds the Mylar and processes the material in the vacuum chamber so it receives a microscopic thin layer of vaporized metallic particles. After processing, the artist pulls the Mylar sheet through the slices he previously made, allowing gravity to pull the translucent material into a seemingly random array of curvilinear shapes. The kinetic sculptures, hung with nearly invisible microfilament, slowly twist in space and reflect ambient light from the surrounding environment. The reflective quality is aided by the vaporized metals, much like the prismatic effect of gas in a puddle of water. "The aluminum acts like water, it raises the reflectivity," Bell explains, "the quartz acts like the gasoline, it interferes with the light reflected off, at wavelengths equivalent to the thickness of the deposit. It's the same story."

Aluminum and silicon monoxide on polyester film

Pacific Red II

Pacific Red II is a striking installation consisting of a series of six nested chevrons, built from two pieces of six-foot-square red glass panels meeting at right angles. The vibrant red hues that first attract our attention soon dissolve to other concerns. Although not immediately apparent, slight variations in the opacity of the red metallic film distorts the viewer's perception; reflections, shadows, and objects alternately disappear and reappear as one walks through the seemingly simple installation.

In his most recent work, Bell has re-imagined his architecturally scaled, immersive installations while pushing his exploration of light in a radical new direction. Instead of translucent shapes that seem to physically dissolve the distinction between object and environment, the brightly colored works radiate a distinct sense of their volume and mass. Varying in color from bright orange, cool blues, frosty whites and blood red, Bell has departed from the metalizing process to laminate large planes of glass in varying shades of film ranging in translucency. The initial assumption concludes that Bell has ventured into a more truly Minimalist vocabulary, with repetitive forms emphasizing notions of space between the units. However, the varying degrees of reflection and transmission of light through the different pieces of glass makes such distinctions impossible to visually detect.

installation view - Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art, Pepperdine University

Biography of Larry Bell

Childhood and Education

Larry Bell was born in Chicago in 1939. The family moved to California in 1945 when Larry was five years old. His father was an insurance salesman and his mother would later re-enroll in community college to study art. The family resided in what was then the rural community of Van Nuys located in the San Fernando Valley, just north of Los Angeles. He recalls being the first family on his street to own a television set, which became a strong influence during his youth.

Bell's formal introduction to art effectively began post-high school when confronted with the choice of, in the artist's words, "school, work or the army." He chose the prior and enrolled in Chouinard Art School in 1957 to study animation with the goal of working at Walt Disney Studios. He had previously attended a summer course at the college on a scholarship fueled by his talent for drawing cartoons.

Part of Chouinard's curriculum required Bell to enroll in painting classes, where he met first-time instructor Robert Irwin who later became a leading figure in the Light and Space movement. Irwin, who has remained a lifelong friend and influence on Bell, exposed the young artist to ideas associated with what he described as "Perceptualism." As defined by art critic Peter Frank for the Brooklyn Rail, the aesthetics of Irwin's 'perceptualism' posits the eye is a gullible organ, "and the brain even more, so that art can make us aware of this by taking advantage of visualization in ways at once pleasurable, illogical, and subversive, even threatening." In addition to Irwin, Bell took classes from influential instructors including Richards Ruben, Robert Chuey, Emerson Woelffer and Herbert Jepson, who earlier founded the Jepson Art Institute (1945-54).

Early Training

Bell created his earliest paintings in the tradition of Abstract Expressionism, still the dominant voice of contemporary art in the United States during the late 1950s. "From here," explains historian Robin Clark at a 2015 symposium for the artist at The Chinati Foundation, "Larry started to eliminate the texture of the brushstrokes, applying opaque color to the unprimed canvas and masking off shapes to create straight-edge parallelograms." After departing from the gestural tradition, Bell explored notions of volume rendered on the flat surface on uniquely shaped canvases.

While on break from Chouinard, Bell worked at a commercial frame shop and would often experiment with leftover framing supplies. One day, he noticed the intriguing effect of light passing through a cracked piece of glass, making three separate lines simultaneously: the shadow, the light and the crack itself. Inspiration struck. Bell first introduced fragments of glass to his canvases in 1959, and within a few years he had integrated both mirrored and transparent glass in multiple collaged constructions depicting geometric forms.

After Chouinard, Bell set up his studio in the coastal community of Venice, CA, alongside many of his peers, including Billy Al Bengston, Ken Price and Robert Irwin. By 1962, Bell had his first of three solo exhibitions at the now-legendary Ferus Gallery (1957-1966), a nucleus of the nascent contemporary art scene then forming in Los Angeles (gallery was co-founded by curator Walter Hopps and artist Ed Kienholz). The innovative gallery programming at Ferus, which includes the first solo exhibition for legendary Pop artist Andy Warhol in 1962, launched the careers of numerous West Coast artists, such as Bengston, Ed Ruscha, Joe Goode, Ed Moses, and Craig Kauffman. Nicknamed the "Cool School," these artists, Bell included, represented a break from the dominance of Abstract Expressionism in Los Angeles. Hopps left Ferus in 1962 to become curator of the Pasadena Art Museum, where he oversaw the first retrospective for the iconic Marcel Duchamp the following year. While Duchamp visited the Los Angeles region in preparation for this survey, he made a surprise visit to Larry Bell's studio, who later recalled being speechless upon realizing just who happened to walk in.

The earliest cube sculptures made their debut at the artist's second solo exhibition at Ferus Gallery in 1963. This led to a group exhibition at Sidney Janis Gallery in New York the following year, which in turn yielded a solo exhibition at the prestigious Pace Gallery in New York in 1965. Shipping the fragile works across country proved difficult and multiple glass panels were damaged in transit. After the costly repair, Bell purchased his own aluminizing machine, putting the creative process entirely within the artist's domain.

Following his sold-out show at Pace, Bell decided to remain in New York where he befriended numerous New York artists, among them celebrated Minimalists Donald Judd and Frank Stella. However, despite the financial success and active contemporary art scene, Bell did not stay long on the East Coast. After just two years, during which he experienced the infamous Northeast Black Out of 1965 and the Blizzard of 1966, the artist decided it was time to leave New York.

Mature Period

Bell returned to Venice Beach in 1967, transporting his vacuum-coating chamber to his re-established Market Street studio. Before long Bell grew restless, feeling he had explored much of the potential offered by the cube sculptures. Also feeling frustrated by the limited scale he could produce with his current technology, he commissioned a custom-built, large-scale vacuum chamber, nicknamed the "the tank," the following year. This new machine allowed Bell to experiment on a much greater scale, enabling him to coat plates of glass up to six-by-ten feet in size.

Within a few years of his return, Bell's life took a new direction. Recently married to Janet Webb, he traveled with longtime friend, innovative ceramic sculptor Ken Price, to Taos, New Mexico. Bell has since described Price as the biggest influence on his sculptural work. This move marks a revival of the modern art community first established in the region during the 1940s. In the earlier period, it was largely New York artists who commuted to the Southwest artistic center, while this revival consisted largely of Los Angeles artists who chose to relocate or spend part of the year in Taos during the 1970s. The initial curiosity with the city is often credited to actor Dennis Hopper, also active in the LA art scene, who first went to Taos during the filming of Easy Rider (1969) and moved to the city shortly thereafter. Bell joined his friends in 1972, at first maintaining his Venice Beach studio until 1975, when he moved the cumbersome vacuum-evaporation system to a new studio in Taos.

Bell has described his move to the desert community as a means to "control his distractions," joking on more than one occasion that he liked the LA art scene perhaps "too much." The change of atmosphere proved both social and environmental. Peter Frank describes in the 1995 catalogue essay, Understanding the Precept, "The brilliant light and emphatic spaciousness of the high desert encouraged a more expansive approach, in terms both of size and of formal elaboration." Over time, the scale of his work significantly increased, culminating with the massive 56-piece installation titled The Iceberg and Its Shadow (1974-77).

The industrial nature of Bell's glass sculptures aligned him with the trend toward art and technology in the 1970s. At the start of the decade, Bell was a participant in the inaugural Art & Technology program at the Los County Museum of Art, which put artists in direction collaboration with leading technology and scientific research companies. That same year, he also collaborated with fellow Light and Space artist Eric Orr on Solar Fountain, a public artwork for the city of Denver, Colorado.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Bell began to experiment with paper and Mylar, in addition to glass sculptures. He concentrated on both the large-scale installations as well as returning to two-dimensional works with multiple series of collaged papers that were also treated with vaporized metals before being assembled together. Later, a collaboration with the renowned postmodern architect Frank Gehry in the early 1990s led to the development of his engaging "stick figure" bronze sculptures. Quite unlike any earlier body of work, Bell used a computer program to render the sketch-like designs for what he titled his Sumer series. Bell explains the designation as a reference to a fictionalized mythology he created that was inspired by the ancient Mesopotamian culture associated with early Bronze Age technology.

Late Period

In 2002, an initiative funded by the Getty Foundation and the Getty Research Institute (GRI), known as Pacific Standard Time, began an effort to conserve and provide an institutional platform for scholarship documenting the historical activity of Los Angeles' postwar art scene. This culminated in 2011 with a series of exhibitions throughout Southern California, collectively titled Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945 - 1980, "exploring the richly diverse and often-overlooked contributions of Los Angeles artists from the post-war period through the rise of the contemporary era." Leading up to and during this period, Larry Bell was featured in over 20 exhibitions related to or inspired by this initiative in Southern California alone. Since then, the artist has maintained an increasingly active exhibition schedule at leading galleries and museums in the United States and internationally.

In the essay Shaping Light (1995), Douglas Kent Hall writes, "As he moves along a continuum, conceiving of new projects and formulating ways to realize them, Bell loops back again and again to ideas and methods he developed earlier. He makes no attempt at repetition: he simply draws to each new idea everything he has previously learned that will help bring the project to life." Bell's most recent work strongly attests to that facet of his working methodology. Recently, the artist was featured in Art Basel in Hong Kong (2016) and the Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art (2017) with a series of large-scale glass installations that recall the scale and monumentality of his earlier Standing Wall series with another ingredient added to the mix. In addition to the optical phenomenon of light, the new works are explorations of pure, unabashed color. Again, Bell pushes the continuum forward unveiling the reserve of unlimited possibilities in his pursuit of light.

The Legacy of Larry Bell

Among the Light and Space artists, Bell found early recognition for his pioneering glass and mirror cube sculptures that proved highly influential among his peers on both coasts, including the likes of Peter Alexander, Frederick Eversley, and Donald Judd. Significantly, Bell's ground-breaking investigations into the amorphous nature of light via such commonplace objects as glass and mirror continues to serve an influential role to later artists. As Stephanie Hanor points out in her essay for the Phenomenal: California, Light, Space, Surface exhibition catalogue, "Such an appropriation of the materials and processes of commercial manufacturing to the production of fine art was becoming increasingly important for American artists and, in particular, young Southern California artists." This legacy manifests in the continued explorations of light, materiality and perception in works by artists as diverse as Dan Graham, Doug Aitken, Olafur Eliasson and Jeppe Hein. As suggested by Hanor's essay, the impact of Bell's contributions has particular sway among the budding generation of artists in Los Angeles, who are similarly preoccupied with exploring the subtle nuances of reflected light, color and perception, including painters Jimi Gleason, Eric Johnson and multi-media installation artist Phillip K. Smith III.

Influences and Connections

-

![Donald Judd]() Donald Judd

Donald Judd ![Robert Irwin]() Robert Irwin

Robert Irwin- Ken Price

-

![Ed Ruscha]() Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha ![Walter Hopps]() Walter Hopps

Walter Hopps- Billy Al Bengston

- Irving Blum

-

![Light and Space]() Light and Space

Light and Space - Perceptualism

- Finish/Fetish

- West Coast Minimalism

- Fred Eversley

- Peter Alexander

- Dennis Hopper

Useful Resources on Larry Bell

- Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960sOur PickAuthor: Hunter Drohojowska-Philps / Publisher: Henry Holt and Co. (2011)

- Made in Los Angeles: Materials, Processes, and the Birth of West Coast MinimalismOur PickBy Rachel Rivenc

- Zones of Experience: The Art of Larry BellOur PickBy Larry Bell, Dean Cushman, Douglas Kent Hall, Peter Frank, Ellen Landis, James Moore / Albuquerque Museum of Art (1997)

- Phenomenal: California Light, Space, SurfaceBy Robin Clark / University of California Press (2011)

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI