Summary of German Renaissance

Though less famous than its Italian cousin, the German Renaissance produced some of the most striking and influential works of art in Western history. At the center of it was the exceptional figure of Albrecht Dürer, a genius and polymath who excelled across a range of media, from painting to woodblock printing and engraving. The latter forms became particularly associated with the German Renaissance, which also saw remarkable developments in architecture that paved the way for the Baroque. On the intellectual and cultural front, everything from the invention of the printing press to the birth of the Christian Reformation can be gathered under the banner of the German Renaissance, which was powered by religious reformers such as Martin Luther and Renaissance Humanists like Conrad Celtes and Willibald Pirckheimer. The German Renaissance was part of the larger, Northern Renaissance of the same era.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The German Renaissance is synonymous with the name of Albrecht Dürer. The son of a goldsmith who produced his first, exceptional self-portrait at the age of 13, Dürer's incredible abilities were matched by his mathematical skill and business acumen. The latter allowed him to master new media such as printing and engraving to sell to an emergent middle class, becoming one of the first independent artists in the sense we understand the term today. In many aspects of his life, Dürer paved the way for the story of art thereafter.

- If the quintessential medium of the Italian Renaissance was the oil painting, the German Renaissance became closely identified with printing and engraving. These modes of production were different from painting in that they allowed multiples of single works to be produced. This, in turn, allowed artworks to be sold en masse and for artists' workshops to achieve a new degree of financial independence. Thus, the German Renaissance foregrounded the demise of religious and aristocratic patronage and the rise of the independent artworld economy with which we are familiar today.

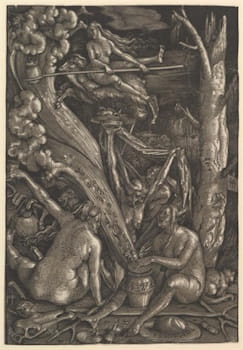

- The dark color palettes and highly wrought textures of printing and engraving, perhaps combined with the gloomier recesses of the Northern imagination, gave many works of the German Renaissance a decidedly grimmer atmosphere than those of the Mediterranean. Hans Baldung Grien's depictions of witches' covens exemplify a regional preoccupation with the occult, with the devil, and with religious trauma and suffering, which is far less prevalent in Italian art of the era. We also find within the German Renaissance, as in the Flemish, a unique preoccupation with peasant life, and an accompanying bawdy and dark humour.

- In Germany, as in other parts of Europe, the Renaissance in art went hand in hand with a Renaissance in academic thought. Germany, however, had the unique advantage that the country was the birthplace of the printing press, and the first place where the technology was widely adopted. As such, artworks, in the form of prints and engravings, were often created explicitly for circulation with Renaissance texts. In this sense, there was a uniquely correlation between the spirit of the renaissance in visual and linguistic media.

Artworks and Artists of German Renaissance

Temptation of Saint Anthony (Torment of Saint Anthony)

Saint Anthony is here depicted as the still point in a swirling chaos of demons, their chimeric and disturbing forms clutching and clawing at him while beating him with sticks. Standing as if rooted in the center of the engraving but placed in space as if floating in air, Saint Anthony's expression is calm and contemplative, turned inward, ignoring the demons who claw with their fingers at his hair or climb up his shoulder trying to pull him downward. With lizard scales, goat heads, forked tongues, and spiky wings, the demons yet act with human cruelty, this combination of familiar and unfamiliar features making the work "uncanny" in the purest sense. Some of the demons even seem to have human sexual characteristics, the work thus evoking the connection drawn in Christian theology between temptation and torment.

Saint Anthony the Great was a fourth-century monk from Egypt who became an anchorite, practicing his Christianity in isolation while living for decades in the desert. He became known as the "father of monks" and had a centuries-long influence on mystical religious practices. The theologian and Church Father Athanasius of Alexandria wrote his Life of Anthony in or around 360 AD, penning the accounts of the anchorite's visions and spiritual battles with the devil or demons which became widely known and popular in medieval art. The British Museum relays Athanasius's assertion that "the rigorous asceticism practised by St Anthony in the Egyptian desert allowed him to levitate in the air, where he was attacked by devils trying to beat him to the ground. The imaginative power with which Schongauer interpreted their assault made this engraving famous throughout Europe."

This print was one of Schongauer's earliest works and it is a true tour de force, particularly in its technical mastery of cross-hatching, which creates the work's amazing textures. The scales, fur, and claws become almost palpable, while at the same time the composition creates a swirling energy that both emphasizes the saint's central position and overwhelms him visually. Schongauer's engraving influenced Dürer's treatment of the devil in Knight, Death and the Devil (1513). The artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari, meanwhile, asserted that Michelangelo's first work, created at 12 or 13 when he began his apprenticeship, was a copy of Schongauer's Anthony, though the claim is debated. Art critic Holland Cotter writes that, "if the Schongauer image was a somewhat unusual choice [for Michelangelo], it might also have represented a gesture of independence, a way for the precocious adolescent to separate himself from the workshop herd."

Engraving - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family

This anonymous portrait depicts a woman in three-quarters pose, holding a bouquet of forget-me-nots as if to her heart. Her dark clothing blends into the dark background, emphasizing her pale delicate hands, her poised and thoughtful expression, and the white Swabian headdress, its stiff folds framing her face. The painting, thought to be a memento mori, has a sense of lightness and wit, as the hint of a smile plays at her lips and a single fly perches on her headdress. As a result the image is both charming and ambiguous, representing the impermanence of life with the forget-me-nots, a symbol of remembrance, contrasting with the transitory life of the fly. At the top of the painting, an inscription gives her name as "Geborne Hoferin", though nothing else is known about her. The work exemplifies the interest in the individual that marked the Renaissance.

The artist, though unknown, also exerts a presence. As art critic Laura Cummings writes of the subject, "her eyes twinkle, and her mouth is halfway to a smile, as if she knows only too well what the artist has done to her: on her copious white veil sits a black fly, positioned as conspicuously as a beauty spot. It lives - the illusion is superb - and it will die, like the brilliant blue forget-me-nots in her hand. Memento mori can be stultifyingly conventional (the skull, the candle), but these are so unusual as to be sharply arresting. And the fly is a proof of the anonymous artist's gifts too: a guarantee of the realism and fidelity of the portrait."

Oil on silver fir - National Gallery, London

The Holy Family

The painting resounds with Christian symbolism, the red of Mary's gown symbolizing the passion of Christ while the grapes in her hand and basket in the left suggest the blood of Christ. A water vessel in the niche behind her alludes to her purity. Additionally, as art historian Cäcilia Bischoff writes, "the emphasis on Joseph as the bread-winner of the family - depicted here with a sheaf of wheat, which simultaneously alludes to Christ's redemption - gained importance in the 15th century. Joseph watches the idyllic scene from the back of the Bethlehem stable and thus reflects the role of the devout viewer."

The artist of this work, Martin Schongauer, was the son of a goldsmith and trained in the family workshop in Colmar, where he also learned engraving. He became particularly famous for his engravings, of which 116 survive, and was called the "Colmar Master". Dying of the plague before his 40th birthday, Schongauer nonetheless had a long-lasting influence, both in Germany, upon such artists as Dürer, and throughout Europe.

The symbolism of The Holy Family reflects the influence of Netherlandish religious painting on the German Renaissance, while the small size of the piece (approximately 7 by 10 inches), as well as the style of composition and detail, are familiar from Schongauer's engravings. As Bischoff notes, "in his paintings Schongauer combined the qualities of his drawings with a Netherlandish style of coloration adopted from Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden".

Oil on beech wood - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Self-Portrait

In this innovative self-portrait, the artist faces the viewer with a compelling gaze, his intense presence offset against a dark background as if he had materialized from another realm.

Bearded, with long flowing hair, and his right hand poised in a calm but instructive gesture, Dürer here resembles Christ the Pantocrator, a term that evoked the "power to do anything," which he seems to appropriate for himself and the figure of the Renaissance artist. As art historian Joseph Koerner writes, "in fashioning his own most monumental likeness after the cultic image of the Holy Face, Dürer makes particular claims for the art of painting. By transferring the attributes of imagistic authority and quasi-magical power once associated with the true and sacred image of God to the novel subject of self-portraiture, Dürer legitimates his radically new notion of art, one based on the irreducible relation between the self and the work of art."

Dürer's first known work is a self-portrait, Self-Portrait at Thirteen (1484), and his oeuvre ultimately became almost synonymous with the spirit of self-portraiture. This 1500 work followed others in the same genre, including Self-Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle (1493) and Self-Portrait (1498). However, this is the most richly complex of the group, its black background and the inscriptions floating beside the artist, placed symmetrically and in line with his gaze, created a sense of charged significance. On the artist's right his monogram, painted in gold, stands beneath the year of composition, while on his left a Latin inscription reads: "Thus I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg, painted myself with everlasting colors at the age of 28 years". As Koerner notes, "Dürer gazes out at us from a completed world in which every hair, every visible surface, is wholly accounted for-as if the moment of self-portraiture had indeed been the total and instant doubling of the living subject onto the blank surface of the panel". The term propriis coloribus ("everlasting colors") is, according to Koerner, "a complex phrase meaning not only 'eternal' or 'permanent' colors, but also colors that are Dürer's very own-colors that are somehow magically consubstantial with the thing they represent."

Dürer's emphasis of the human form and interest in self-portraiture bears out his assertion: "I hold that the perfection of form and beauty is contained in the sum of all men". Man as the measure of all things was a central tenet of Renaissance Humanism, placing the individual, rather than God, at the center of the universe. This work is one of the most significant and iconic in art history and has influenced countless artists. Some contemporaries responded to the image in more overtly religious works, as in Sebald Beham's woodcut, The Head of Christ Crowned in Thorns (ca. 1520) and Georg Fischer's painting Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1637). But the more profound and long-lasting influence of the piece is in pioneering the idea of the artist as the measure of all thingxxx, an individual human worthy of reflection and reverence, an ethos echoed in famous self-portraits of subsequent centuries, from Rembrant to Van Gogh to Frieda Kahlo.

Oil on wood panel - Alta Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

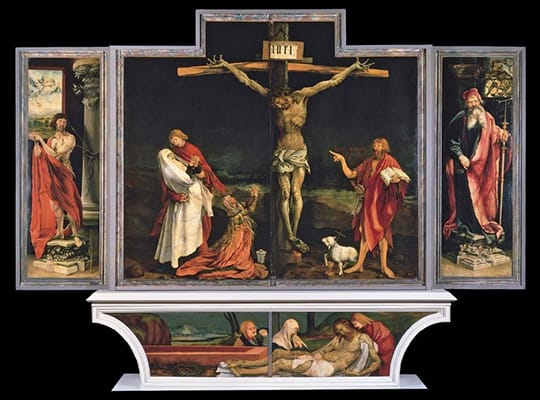

The Isenheim Altarpiece

This famous altarpiece depicts the crucifixion of Christ, his torn and twisted body rigid in death, his flesh beginning to decay. Grünewald combines the Renaissance's realistic observation and compositional principles with the fervor of the medieval imagination, depicting the reality of death. The cross-shaped frame echoes the importance of the crucifixion, while the figure of Christ is exaggerated in scale for emotional effect, as his fingers seem to claw at the black sky above him. Christ is surrounded by several figures. On the left, the Virgin Mary in white, her hands clasped in a gesture of pity, leans backward, almost falling, as she is cradled by John, the beloved disciple. Indicating that the work occupies a sacred space, outside of time, the work brings together the living and the dead. Kneeling at the foot of the cross, Mary Magdalene reaches upward, her clasped hands pleading, while John the Baptist, who had previously been executed by Herod, is depicted on the right, as he holds an open Bible and points toward Christ.

The Monastery of St. Anthony commissioned this work for its hospital, which treated those suffering from St. Anthony's Fire, now known as ergotism, caused by eating infected rye. Common in the Middle Ages, the disease caused severe inflammation, convulsions, and gangrene, and the patients in the hospital may have identified their own state with that of Christ. The resultant work was in fact a collaboration between Matthias Grünewald and the Gothic sculptor Nikolaus Hagenauer, and is designed to be viewed in stages corresponding to the religious calendar.

This work had a long-lasting impact and influence, particularly on the German Expressionists, including Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann. For the composer Paul Hindemith, whose opera about Grünewald, Mathis der Maler ("Matthias the Painter" 1933-35), could only be performed after he had fled Nazi Germany for Switzerland, this Renaissance work spoke to the dark spirit of the present. "[Grünewald's] paintings tell us vividly how the wild times with all their misery, their illnesses, and their wars unnerved him. How bottomless must have been the abyss of fickleness and despair that he navigated when, at the threshold of modern times, he gave intimate expression one more time to medieval piety."

Oil on panel - Musee d'Unterlingen, Colmar

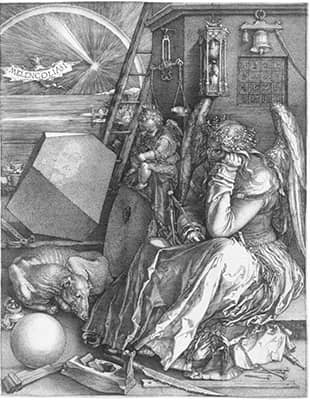

Melencolia I (Melancholia 1)

This famous engraving depicts an angel, holding her head in her left hand and calipers in her right, as she broods in the foreground. She stares grimly into the distance, ignoring putto scribbling on a slate next to her, the emaciated dog curled up as if shivering, and all of the instruments of power before her: from the magic square above her to the geometric and architectural tools scattered at her feet. Lacking a visual center, with the angel skulking on the right against the corner of a cluttered building, and the array of mystifying objects on the left, the image creates a sense of abandonment and disorder.

This work is one of three plates often grouped together and referred to as Dürer's Meisterstiche ("Master Prints"), also including Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513) and St. Jerome in his Study (1514). The objects that populate the scene are of great significance to the themes of Renaissance Humanism. As art historian Erwin Panofsky noted, the tools on the ground "mostly pertain ... to the crafts of architecture and carpentry. In addition to the grindstone ... we find: a plane, a saw, a ruler, a pair of pincers, some crooked nails, a molder's form, a hammer." For Panofsky, "these symbols or emblems bear witness to the fact that the terrestrial craftsman, like the 'Architect of the Universe', applies in his work the rules of mathematics, that is, in the language of Plato and the Book of Wisdom, of 'measure, number and weight'." The emphasis on geometry also reflects Dürer's personal interest in the mathematics of artistic composition. The oddly shaped stone cube or "polyhedral" portrayed on the left has fascinated mathematicians for centuries, and was even the subject of a conference, 500 Years of Melancholia in Mathematics, held at New York University in 2014.

Yet, in spite of this emphasis on human endeavor and achievement, the subject of this engraving is despair and depression. The angel's dark temperament expresses the melancholia of the title, which is announced on a banner held by a bat-like creature in the upper left. The term "melancholia" also refers to one of the four humors that defined human temperament according to a theory prevalent at the time, the condition caused by an excess of "black bile". Dürer was aware of the work of Cornelius Agrippa, the German Renaissance scholar whose De occulta philosophia libri tres ("Of Occult Philosophy in Three Volumes" [1510]) connected melancholia to genius, artistic creativity, reason, and spirit. This work has thus often been interpreted as depicting the artist's own temperament, both brooding and brilliant. Erwin Panofsky called it the artist's "spiritual self-portrait".

This work has been the subject on endless speculation in the centuries since its creation. As art historian Joseph Leo Koerner writes "the vast effort of subsequent interpreters, in all their industry and error, testifies to the efficacy of the print as an occasion for thought. Instead of mediating a meaning, Melencolia seems designed to generate multiple and contradictory readings, to clue its viewers to an endless exegetical labor until, exhausted in the end, they discover their own portrait in Dürer's sleepless, inactive personification of melancholy. Interpreting the engraving itself becomes a detour to self-reflection".

Copper engraving print - Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Donaulandschaft mit Schloss Wörth (Landscape of Danube near Regensburg)

This evocative view opens upon the Danube River Valley, framed by a tall evergreen tree on either side. A road winds through the dense forest of firs and larches from the foreground, its silhouette emphasized by the mountains rising behind it, as the morning sun rises. The work reflects Altdorfer's fascination with the play of light and color. The soft gold and pink of impeding dawn contrasts with the blue and grey tones of the clouds filling the upper two thirds of the painting, their billowing forms dramatically edged with light.

Altdorfer's interest in formal innovation, meanwhile, is reflected in his use of repoussoir, a technique developed at the end of the Italian High Renaissance which he introduced to German artists. The term refers to the placement of objects or figures at the foreground edge of a painting to frame the scene and guide the viewer's eye inwards. In this case, the two evergreen trees to the fore frame the winding path to Wörth Castle.

Altdorfer was a leading artist of the Danube School, where he pioneered the development of landscape painting as an art in its own right, through the above work amongst others, including Landscape with a Foot Bridge (ca. 1518-20), perhaps a slightly earlier composition. Around the same time, the Flemish Renaissance painter Joachim Patinir was developing what was called the "world landscape". However, Patinir's panoramic views were always the background to religious scenes, as in Landscape with St. Jerome (1515-19). In contrast, Altdorfer's smaller works depicted only the landscape, devoid of human figures. This would prove to be the more enduringly influential approach to landscape painting. Indeed, Altdorfer and the Danube School's interest in the natural world on its own terms is seen as a forerunner to the Romantic painters and, beyond that, the Realist and Impressionist schools.

Parchment on beech wood - Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Portraits of Martin Luther and His Wife, Katharina von Bora

This pair of small tondos (circular artworks) depicts Martin Luther, the former priest who launched the Protestant Reformation, and his wife, Katharina von Bora, a Cistercian nun at the time of their marriage. Dressed in black, Luther is depicted in three-quarters profile, turning to gaze at his wife while she looks forward at the viewer. The medallion-like portraits emphasize the rectitude and propriety of the couple's union and their stern strength of character, emphasized their simplicity of dress, forthright expressions, and plain background.

A witness at Luther and Katharina's wedding, Cranach was a close friend to the dissenting preacher and had previously portrayed him as an Augustinian monk, at the time he was starting to challenge the authority of the Pope. Printing and disseminating Luther's pamphlets calling for reform, Cranach became an artistic leader of the Reformation, and portrayed Luther on multiple occasions, sometimes portraying with his wife or with other Protestant leaders such as Philip Melanchthon. Several versions of this portrait exist, and Cranach and his workshop were to create larger diptychs that could be displayed and revered in Lutheran homes.

The work was, in part, produced as a piece of propaganda for Luther's dissenting views on clerical marriage. He had questioned the Catholic church's requirement of clerical celibacy. Thus, as a memento of his marriage to a nun, Cranach's dual portrait codifies a profound religious and cultural schism. Anticipating criticism and outcry, the artist emphasized traditional aspects of the union, such as placing the bride on the viewer's right, the heraldic left or "sinister" side, reflecting her lesser status. In addition, the tondo portraying him is slightly larger. The dark blue background of each portrait evokes heaven's blue, while being unbound in detail to any particular time and space. Marriage portraits of Luther and Katharina were widely circulated at the time. As the Cranach Archive notes, they had "the function of documenting their relationship" while also "present[ing] the reformer in new private and public contexts", prompting tthe viewer to "imitate the exemplary Christian way of life embodied by him".

Oil on panel - The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Darmstadt Madonna

This masterwork depicts the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Jesus, surrounded by Jakob Meyer and his family, who kneel before her in reverential poses. She is depicted as a Schutzmantelmadonna or Virgin of Mercy, a traditional treatment that shows the Madonna as covering those in need of comfort with her mantel; in this case her cloak extends over Meyer's shoulder to the left. She is framed with a scallop shell, a symbol of femininity and the divine, while she wears the hooped crown, evoking the German crown and conveying her sovereignty as Queen of Heaven. On the left, looking upward, his hands clasped in prayer, is Meyer himself, the "Bürgermeister" (Chief Magistrate or Mayor) of Basel, who commissioned the work and whose importance is conveyed by the scale of his figure, approaching that of the Madonna.

The portrait is unusual in that Meyer wanted all of his family members, whether living or deceased, to feature in it. On the left are his two deceased sons while on the right three women appear, his living daughter, second wife Dorothea Kannengeisser, and finally Magdalena Baer, his first wife, who had died in 1511. As the artist had never seen Magdalena and Meyer's two sons, he drew upon artistic sources for inspiration. Thus the two boys, one of them dressed in finery and attending to the other, a nude infant, evoke Italian Renaissance paintings, particularly those of Raphael and Leonardo. Noting the influence of Andrea Mantegna upon this work, art historian Franny Moyle adds that the "perspectival approach ... is almost identical" to Mantegna's Madonna della Vittoria (1496).

This painting is also notable for conveying a Renaissance Humanist emphasis upon the individual. The feeling of care and protection between the two boys, and the warmth and intimacy of the Madonna cradling her child, are palpable. Meanwhile, Magdalena Baer, her face barely visible and shrouded by her white headdress, looks toward Mary in evident grief and loss. At the same time, the painting indicates Holbein's mastery of perspective and illusion, as the boys look downward as if toward the rumpled carpet, drawing the viewer's attention to a section of the floor which seems to lift upwards, threatening to trip the baby. This kind of technical mastery and precision, rooted in a mathematical understanding of the craft of painting, was another feature of the artistic Renaissance in Germany and elsewhere.

Oil on pine wood - Museum Würth, Künzelsau, Germany

Battle of Alexander at Issus

This historical painting depicts the Battle at Issus, where Alexander the Great defeated Darius III, the Persian king, in 333 BCE, thus conquering the Persian Empire. The panoramic world landscape surges with soldiers, on foot and carrying banners on horseback, their dark shining armor a single wave which swallows up individual forms, the fallen trampled underfoot. Standing in his chariot drawn by three white horses, Darius tries to muster his troops to him as he is pursued by Alexander and his cavalry. Alexander leans forward, driving his chariot, his lance the vanguard of his cavalry, the bristling sea of their lances surging behind him. Critic Jonathan describes the work as "the quintessence of German Renaissance art: every mountain a colossus, every ray of sun an apocalyptic beam of fire from heaven, every cloud a glimpse of the infinite. This is war as unholy spectacle".

Duke William IV of Bavaria commissioned this work for his residence, where it was meant to hang with a series of paintings depicting events from Roman history and mythology, such as The Siege of the City of Alesia (1533) by Melchior Feselen or The Martyrdom of Marcus Curtius (1540) by Ludwig Refinger. However, Altdorfer was a pioneer of landscape painting, and, even in his many religious works, he created majestic landscapes using dramatic, almost expressionistic treatments of water and sky. This particular scene was inspired by views of the Alps and the Danube River valley, contemporary maps, and the artist's imagination. In the distance an imagined mountain, framing a castle, forms a kind of secondary horizon. Beyond it, the landscape shifts to blue and silver, indicating the waters of the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Nile River, rising up to a dramatic sky where the sun sets in a swirl of burning gold.

As befitting historical and religious paintings, many of these elements had symbolic meanings. Alexander was often associated with the sun, while the crescent moon hanging to the left encapsulated the power of the East as the Persian Empire wanes. According to art historian Larry Silver, Altdorfer's paintings often depict "celestial phenomena, which explicitly serve to link heaven and earth and underscore the significance of the depicted event". Meanwhile, the red signifies the sacrifice of those slain or wounded, while an inscription in the sky evokes the Biblical prophecies of Daniel, who predicted the fall of four great kingdoms before the Second Coming. Perhaps most notably of all, Altdorfer portrayed the armies of the East and West in sixteenth-century clothing, alluding to the recent defeat of Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire at the Siege of Vienna in 1529.

Oil painting on wood - Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Heidelberg Castle, Prince-Electors Friedrich II, Ottheinrich, Friedrich IV, Friedrich V

This famous ruin, surrounded by lush forest, towers over the Neckar Valley, its red sandstone silhouette creating a sense of grandeur and romantic mystery. Dating back to 1225 and perhaps earlier, the castle became a famous example of German Renaissance architecture, embodying the various stages of architectural development in majestic structures. As the castle's website notes, "Until the Thirty Years' War, Heidelberg Castle boasted one of the most notable ensembles of buildings in the Holy Roman Empire. In brisk succession, the prince electors commissioned a series of imposing constructions ... Each one is a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture. Their magnificent façades create a resplendent frame for the courtyard."

These structures had been built by successive rulers, or Prince-Electors. Prince-Elector Friedrich II built the Gläserner Saalbau, or Hall of Glass, in 1549, with arcades on each of the façade's three levels. This early style of German Renaissance architecture was heavily influenced by Italian architecture and the structure was named for the second floor's Venetian mirror glass, which no longer survives. Subsequently, Prince-Elector Ottheinrich began building the Ottheinrich Wing (Otto Henry Wing) in 1556, perhaps the most famous German Renaissance palace, with mythological statues by Alexander Colin adorning the pediment. Most notable in this photograph is Friedrich's Wing (1601-07), built by Prince-Elector Friedrich IV, the large ornate building with dwarf gables which stands left of center. Again, the façade is also decorated with sculptures, by architect Johannes Schoch and sculptor Sebastian Götz, and depicting the ruler's ancestors. Though the castle was damaged by fire, it is the best preserved of the Renaissance structures and was also partially renovated in the late nineteenth century. The last palace structure was the English Wing, which Prince-Elector Friedrich V began building in 1612 as a residence for himself and his English wife. Informed by the design principles of Andrea Palladio, the famous Italian architect, its classical clean lines are visible a little right of center.

The castle has been the repeated victim of historical misfortune, from sieges to its captured in the Thirty Years War, two attacks from the French army during the Nine Year's War (1688-97), and even lightning strikes. As Victor Hugo, the noted French author, wrote after visiting the site in 1838, "what times it has been through! Five hundred years long it has been victim to everything that has shaken Europe, and now it has collapsed under its weight." As a ruin, the castle became famous, drawing artists and writers, a pilgrimage which continues into the present. Mark Twain popularized the site for Americans when he wrote in 1880: "a ruin must be rightly situated, to be effective. This one could not have been better placed. It stands upon a commanding elevation, it is buried in green woods, there is no level ground about it, but, on the contrary, there are wooded terraces upon terraces, and one looks down through shining leaves into profound chasms and abysses where twilight reigns and the sun cannot intrude."

Red sandstone - Heidelberg, Germany

Beginnings of German Renaissance

Albrecht Dürer

Any account of the art of the German Renaissance must begin with Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), an extraordinary talent and one of the most important figures in the history of Western art as a whole. As the critic Jacob Wisse notes, "Albrecht Dürer was the quintessential artist of the German Renaissance." Trained as an engraver in his father's workshop, Dürer soon revealed the artistic powers that made him a prodigy of the age. His Self-Portrait at Thirteen (1484), done in silverpoint, is his first-known work and already indicates his mastery. Silverpoint involves using a metal stylus (commonly made of silver, hence its name) to draw on a surface prepared with a mixture of bone ash and glue. The Italian artist Cennino Cennini included the technique in Il Libro dell'Arte (Book of Art), his early fifteenth-century manual of early Renaissance media and techniques. Used for preparatory sketches and as a training technique for artists, it was favored by Renaissance artists such as Leonardo da Vinci.

Drawn to Italy in his early twenties, Dürer visited the country for an extended stay in 1494 - he would return in 1505 - to study Classical art as well as the works of the Italian Renaissance and Humanism. Italy was the cradle of the European Renaissance and it was inevitable that a singular talent such as Dürer would be attracted from his own region of the continent, often seen as having been less culturally advanced at this time. As Wisse writes, "more than any other northern European artist, Dürer was engaged by the artistic practices and theoretical interests of Italy." His interest in the Italian Renaissance is expressed in the altarpiece Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506), which shows the influence of Venetian color and has been described by art historian Olga Kotková as "born of the conjunction of two traditions: those of Germany...and of Venice".

Additionally, Dürer was the leading theoretician of the German Renaissance. As Wisse notes, "hundreds of surviving drawings, letters, and diary entries" attest to "his insistently scientific perspective and demanding artistic judgment". Dürer's illustrated text Underweysung der Messung ("Understanding Measurement") (1525) presented his geometric theories and was the first scientific discussion of perspective by a Northern European artist. He also wrote Vier Bücher von menschlichen Proportion ("Four Books of Human Proportion") (1532), in which he stated that, "if you wish to make a beautiful human figure, it is necessary that you probe the nature and proportions of many people."

The National Library of Scotland states that "Dürer used two methodologies for his research. In the first instance, the distances between clearly defined points on the human body were measured and expressed mathematically in relation to the model's total height. By analysing the resultant data and eliminating aberrant figures, he was able to obtain typical values. Using the second method, Dürer divided the height of the human figure into six equal parts in order to obtain a mathematical gauge that was then used for all subsequent measurements. This gauge, or unit of measurement, would differ from one model to the next". Dürer's forensic enquiries into the technical requirements of his craft match those of another great polymath, Leonardo Da Vinci, and indicate a comparable significance to the emergence of Renaissance ideals.

Renaissance Humanism

Humanism in the context of the Renaissance indicates a belief system that emphasized human achievement and potential, turning to the examples of Greco-Roman art, technology, and social organization for inspiration. The emergence of Renaissance Humanism can be seen as a major factor in the shift from the medieval to early modern era, and a relative diminishment of religiosity and superstition as factors determining human affairs.

Dürer was profoundly interested in Humanism and developed lifelong friendships with the leading German humanists Conrad Celtes and Willibald Pirckheimer. He also played a role in establishing Nuremburg, his own home city, as a leading center of German-Renaissance Humanism. Not only was Nuremberg the base of Celtes, Pirckheimer, and scholar and cartographer Hartmann Schedel, it was also visited by leading figures from abroad, such as the great Dutch scholar Erasmus, a close friend of Pirckheimer's.

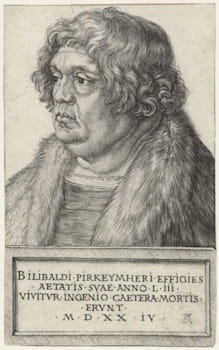

Pirckheimer was widely accomplished. A lawyer by training, he served both as imperial counsellor and on the Nuremburg city council, and was a noted translator and leading art patron. He also became a lifelong supporter of Dürer, financing the artist's 1506 visit to Italy. Pirckheimer is thought to have played a key role in introducing Dürer - who was never formally educated - to classical texts, many of which Pirckheimer himself had translated. (The translation of great classical texts was a major feature of Renaissance Humanism.) In the second of two portraits of Pirckheimer, created in 1524 when the sitter was 53 years old, Dürer included a Latin inscription: "We live by the spirit. The rest belongs to death," honoring his friend and patron in words that also expressed humanist philosophy.

Pirckheimer is thought to have introduced Dürer to Conrad Celtes, and the two men became lifelong friends. Named poet laureate by Emperor Frederic III in 1487 in Nuremburg, Celtes was known as the "Archhumanist," an advocate of Humanist ideals for their own sake rather than as addendums to Christian ethics. His expansive interests included mathematics, the natural sciences, poetry, and rhetoric, and his first major publication, Germania Illustrata ("Illustrated Germany") (1500), advocated for German culture.

This endeavor was partly rooted in a sense of injustice at how Germanic culture was viewed in Italy. Having visited Italy in 1486, Celtes was taken aback that many of his Italian peers viewed Germans as Barbarians, whose Humanism was imperfect as it did not, like their own, draw on classical Roman roots. Germania Illustrata thus draws attention to Germany's many accomplishments and cultural riches, indicating the country's parity with Italy.

Dürer paid homage to Celtes shortly after his death in The Martyrdom of Ten Thousand (1508) depicting the legend where the Roman emperor ordered the King of Persia to kill ten thousand Christian soldiers on Mount Ararat. The two men, dressed in black, are engaged in an intense conversation. They seem to bear witness to, but stand back from, the scene of cruelty around them. Dürer's painting emphasizes his friend's belief in reason and intellectual inquiry and rejection of religious extremism.

Drawings and Engravings

If the oil painting can be seen as the quintessential medium of the Italian Renaissance, we can make a similar claim for printmaking and engraving in Germany. The former technique had a centuries-old history, woodblock printing having been invented in China in the ninth century, and had found its way to Europe by the early 1400s. It was taken up with particular enthusiasm by German-Renaissance artists. It is not coincidental that a German goldsmith, Johannes Gutenberg, had also invented the first printing press in 1440. As art historian Wendy Thompson writes, many of the first German-Renaissance wood-cuts "served as illustrations for the new printed books and the demands of book illustration caused the medium to become more sophisticated and its subject matter more varied." Dürer became the master of woodblock illustration, as Thompson notes, transforming the medium with "such fully realized works in black and white, complete with subtle gradations of tone and suggestions of texture, that Dürer's contemporary, Erasmus of Rotterdam, claimed that to add color would be to "injure the work."

As for engraving, the Alsatian goldsmith and painter Martin Schongauer is credited with having developed the technique around 1430. He became the first artist famous both for his painting and for his engraving. Engraving is an "intaglio" printing process, meaning the creation of the image involves cutting into the printing surface and inking the recessed areas. A cutting tool called a burin was used to incise the design into a polished copper plate, which was then inked and pressed onto the page or sheet. As the Art Institute of Chicago writes, Schongauer's "early training as a goldsmith is evident in the refined engraving technique and the attention to minute surface decoration", while "his rendition of complex spaces, solid volumes, and tonal variation reflect his parallel practice in painting."

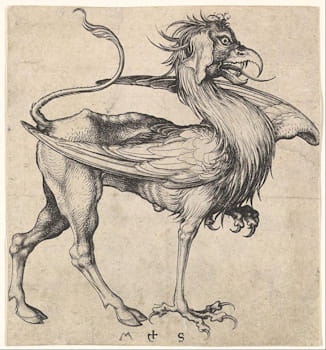

Schongauer's Griffin (1470-91), depicts the legendary animal from ancient Mesopotamia. By the medieval era, the creature's dual nature - here combining the head and wings of an eagle with the body and tail of an ox - was often used as a symbol of Christ's duality, both human and divine. Schongauer's skill was such that Dürer hoped to study in his workshop, though Schongauer's early death from the plague precluded that. Nonetheless, as Wisse writes, Dürer revolutionized this medium just as he had woodblock printing, "elevating it to the level of an independent art form. He expanded its tonal and dramatic range, and provided the imagery with a new conceptual foundation."

After his visits to Italy, Dürer was almost transplant the the principles of the Italian Renaissance into Northern Germany at his workshop in Nuremburg. His subject matter including religious and allegorical themes, often tackled in series such as his Apocalipsis cum figuris ("Apocalypse with Figures") (1498), a set of 15 woodcuts showing scenes from the Book of Revelation, including, most famously, his Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1497-98). This work made him famous, and he would create other cycles based on religious subjects such as The Passion (ca. 1497-1500).

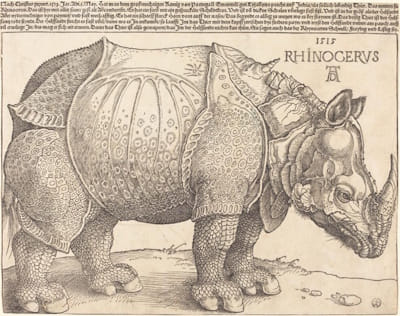

Dürer's individual prints and smaller groups of printed works, as Wisse explains, were "intended more for connoisseurs and collectors than for popular devotion. Their technical virtuosity, intellectual scope, and psychological depth were unmatched by earlier printed work". Endlessly inventive, Dürer also depicted unexpected subjects, such as The Rhinoceros (1515), his most popular woodcut. In 1515, an Indian rhinoceros was brought to Lisbon by Portuguese explorers, the first time the species had been seen in Europe since the Roman era. Extraordinarily, given its great physiological accuracy, Dürer never saw the Rhino, instead basing his work on a written description and brief sketch sent by a merchant to a friend in Nuremberg. At the top of the image, Dürer's inscription uses the description of the rhinoceros from Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia ("Natural History") from the first century. His image thus combines the spirit of discovery and scientific wonder of his own time with knowledge of the classical world.

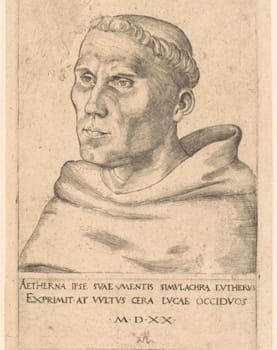

Other noted engravers of the era included Lucas Cranach the Elder, Albrecht Altdorfer, Hans Baldung, Augustin Hirschvogel, and Hanns Lautensack, as well as the group called The Little Masters. As prints could be produced in multiples and widely distributed, some artists became part of the effort to proselytize on behalf of the Reformation through written matter, as in Cranach the Elder's portrait print of the Reformation theologian and figurehead of Protestantism Martin Luther (Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk [1520]). Cranach also distributed Luther's pamphlets challenging the authority of the Pope and the Catholic Church's practice of selling indulgences. And the artist and his workshop produced likenesses of Luther's family and other leaders of the Reformation, as well as creating images that emphasized Protestant themes.

Schongauer's student Hans Burgkmair developed the "chiaroscuro" (meaning depicting light and shade) woodcut in 1509, following his invention of the "tone block" in 1508. Chiaroscuro woodcuts involved printing a line block for the design, with contours and cross-hatching added to indicate shadow through a series of different "tone blocks" which added varying regularity of marks to the sheet to suggest color gradients. Burgkmair's Lovers Surprised by Death (1510) was the first print to use three tone blocks and to be printed only in color (that is, without any true black). The image depicts a young couple in classical Rome who have been ambushed by death, a skeletal winged figure that kneels on the fallen man, a soldier, while the woman turns frantically to flee.

Other prints of this period show the darker and more supernatural themes which mark out the German Renaissance from the Italian, and gave rise to many of the tropes that we now associated with "Gothic" art and style. The artist Hans Baldung Grien, for example, who worked in Dürer's workshop during 1503-07, excelling at color woodcuts and using tone block to create mood, created many works on the theme of witches. This concern with errant female power indicates a strong current of misogyny in early Protestantism, connected in part to the demise of the Virgin Mary as a figure of worship.

Grien's Witches' Sabbath (1510) depicts three nude witches gathered around a cauldron in a dark and sinister forest, while another witch flies overhead. As the British Museum writes, "Baldung's obsession with magic and witchcraft gave vivid expression to the fears of religious heresy, social dissolution, and hidden female powers that preyed on the late medieval imagination". The woodcut was published in Strasbourg, whose bishop, as the Museum notes, was enforcing a papal bull against witchcraft in 1484. Three years later, the Malleus Maleficarum, a handbook for rooting out witchcraft, was also published in Strasbourg, running to many editions.

Woodblocks were widely reproducible, including as illustrations to books created on Gutenberg's new printing press. As such, they were coveted by a rising middle class as well as by aristocrats and collectors. Prints thus provided a steady stream of income to artists. Some artists also designed for the applied arts, creating stained glass, decorative patterns, and jewelry. According to the Getty Center, "important artistic centers included Strasbourg and Basel in the Upper Rhine region, where Martin Schongauer, Hans Holbein the Younger, and Urs Graf were active; Nuremberg, home of Albrecht Dürer and his school; and Wittenberg in northeastern Germany, where Lucas Cranach the Elder served as court painter to the dukes of Saxony."

Printmaking during the German Renaissance transformed the role of the artist by allowing them to take all elements of a work's creation "in-house", and giving rise to the idea of the artists as lone creative genius that became ever more dominant over the course of modern art history. Once again, Dürer is the preeminent figure here, as art historian Joseph Koerner explains: "in producing his woodcuts, Dürer monopolized all stages of an image's making, from invention and execution to publication and sale. He thus freed himself from any dependency on the large book publishers." More than anyone else Koerner notes, Dürer thus "transformed the conditions of the trade for artists working in Germany. What had been a craft financed by commissioned works, and organized in large hierarchically organized shops, became through him a more diversified industry, producing a range of commodities." The end result was the now familiar notion of "a work particular to the singular master".

Architecture

Within architecture, the impact of the German Renaissance often took the form of renovations and additions to pre-existing structures in an older, Germanic Gothic style (in this case meaning ornate religious and civic architecture of the middle ages). For example, pilasters (columns integrated into walls) and pointed gables were added to buildings. Triangular pediments appeared above windows. Balustrades (decorative railings) with sculpted figures were incorporated into other structures. Drawing on classical architecture, regional rulers used such flourishes to lend a sense of legitimacy and grandeur to their power, the mixture of styles embraced with a kind of bravado. The emphasis upon decorative elements within German Renaissance architecture means that it arguably became a kind of pastiche, paving the way for the Baroque.

One example of the difference between German and Italian Renaissance architecture can be found at the Landshut Residence, which includes two palaces. One is the "German Building", named for its German Renaissance style, and the other is the "Italian Building", in an Italian Renaissance style. In 1536 Bernard Zwitzel, an architect from Augsburg, began work on the German Building for Louis X, Duke of Bavaria. At the same time, the Duke had been impressed by Palazzo del Té, built by Giulio Romano in the Mannerist style, on his recent trip to Italy. Wanting a residence to match its splendor, he commissioned Italian architects to begin building an Italian Renaissance palace in 1537. The Bavarian Administration of Palaces, Gardens and Lakes describes the result as "an artistic and architectural gem". While the German building incorporates some triangular pediments it is a more austere and block-like structure, whereas the Italian building includes columned open walkways around an interior cloister, and more high-Renaissance decorative elements.

Another famous example of German Renaissance architecture's mingling of motifs is Heidelberg Castle. Admittedly, the fame of this building primarily derives from the later, Romantic period, when its picturesque ruins drew famous artists and writers such as J.M.W. Turner, Mark Twain, Victor Hugo and Johann Wolfgang Goethe. By that point, much of the castle had been destroyed by the French army in the Nine Year's War (1688-97) but the facades of Ottheinrichsbau (Otto Henry Wing) (1556-59) and Friedrich's Wing (1601-07) remained.

The Otto Henry Wing, named for the ruler who commissioned it, employs a Renaissance style with some Flemish influence. Architect Johannes Schoch built Friedrich's Wing for Prince-Elector Friedrich IV in a late Renaissance style with a richly decorated façade, pilasters, and gables approaching Baroque elements. Both facades were decorated with statues depicting ancient heroes, Roman emperors, and idealized ancestors, creating a classical ambience and indicating that the rulers were descended from illustrious royal lines. The ruin of Heidelberg Castle also contains the early Renaissance Hall of Glass, influenced by Italian architecture, and the English Wing (1612-14), based upon the work of Andrea Palladio, the famous Venetian Renaissance architect and theorist.

As the new ruler of Bavaria and an ardent proponent of the Counter Reformation, Duke William V commissioned Federico Sustis, his court architect, to build St Michael's Church (1583-97) in Munich. This Jesuit church was built in the Renaissance style, as the church's website notes: "the duke had been educated by Jesuits himself. In his eyes, the tradition of Renaissance Humanism seemed ideal for shaping Bavaria in the Catholic spirit." As this might suggest, in spite of its connection to Humanist and German-Renaissance ideals, the church became became a center of the Counter Reformation.

Various civic buildings were also created in a Renaissance style. A noted example is the Augsburg Town Hall (1615-24) built by Elias Holl, the most famous of late German Renaissance architects. He was originally commissioned to renovate the existing fourteenth-century Gothic town hall, but the city government ultimately decided to build a new town hall instead, which became an iconic landmark.

Metalwork

Many German Renaissance artists were trained as goldsmiths, and continued to apply their skills in metalworking having imbibed the new spirit of the times. Creating cups and plates, portrait medals, armor, jewelry, or decorative motifs, they developed new, Renaissance-era designs, such as the columbine cup and new types of portrait medal. The columbine cup, so named because it resembled the inverted blossom of the columbine flower, was developed in Nuremburg by 1513. The ornate cup became so popular that any journeyman applying for master status in a craft guild was required to make one, as well as a gold ring-set, and a die or matrix for making seals.

Portrait medals were first created by Italian artists, but German artists such as Dürer approached the form in new ways. As the website of The Frick Collection notes, "portrait medals are one of the most important artistic inventions of the Italian Renaissance", their primary function "to pay tribute to individuals and to shape and promote their identities." This indicates the new emphasis on individual human identity as a matter of interest and concern during the European Renaissance.

Rather than using the Italian technique of wax modeling, German artists created moulds for their portrait medals from carved stone or wood. The resultant works were much in demand from the merchant class of Nuremburg and Augsburg. As critic Stephen K. Scher states, these tokens of status "expresse[d] the character and aspirations of the period to perfection, transmitting within a small yet complex object the fierce pride and self-conscious dignity of Renaissance man."

Often called the greatest Mannerist goldsmith in Germany, Wenzel Jamnitzer was known for his highly inventive objects, including scientific instruments. Influenced by Italian Renaissance design, his jewelry boxes, vases, cups, small decorative caskets often innovatively incorporated organic materials such as shells and birds' eggs. Born in Vienna, he moved to Nuremberg in 1534 and directed the city mint there, later representing the Nuremburg Goldsmiths on the city council until his death in 1585.

Regional Movements

Danube School

The Danube School is a name given to a loose association of artists who depicted the picturesque landscapes of the Danube River in Bavaria and Austria during the early 1500s. Lucas Cranach the Elder was an important early influence on the group, because of his treatment of landscape and his knowledge and advocacy of Renaissance Humanism, informed by his friendships with Johannes Cuspinian and Conrad Celtes.

The school's preeminent artist was Albrecht Altdorfer, who pioneered landscape as a subject in its own right. Expressive and poetic, his works explore the play of light and color, as in Landscape with Footbridge (1518-20). Showing a bridge crossing a river with a village and mountains visible in the distance, the painting is an early example of "pure" landscape painting, devoid of any human figures and with no historical or mythological scene unfolding within it.

When Altdorfer produced more allegorical, religious works, with scenes always placed in powerfully-rendered landscapes. As art historian Larry Silver writes, "Altdorfer is justly celebrated as a major virtuoso", and notes that modern critics can over-emphasize the element of pure landscape in his oeuvre because we recognize it from schools we are more familiar with, such as Romantic and Impressionist painting. "What is often forgotten in our modern haste to identify our own roots in these visual innovations is that Altdorfer's pictures almost invariably represent religious narratives and their settings calculatingly situate those sacred events in appropriately sacred spaces, even when those spaces consisted of powerful renditions of natural wildernes." Other artists associated with the Danube School are Wolf Huber, Jörg Breu the Elder, and Rueland Frueauf the Younger.

The use of "Danube School" has recently became somewhat contested. As critic Christopher Wood explains, "the term Donaustil (Danube style), which was coined in 1892 by Theodor von Frimmel, had become a code word for sympathy for the local and the popular, for nature over civilization, for an anti-cosmopolitan perspective on art history, art, and life." But this idea has been re-evaluated by art historians such as Margit Stadlober, who have argued that the Danube school indicates a bridge from Gothic to Renaissance concerns and from religious to modern subject-matter.

The Little Masters

The Kleinmeister, or The Little Masters, were a group of sixteenth-century artists known for making small prints - sometimes as little as 1.5 by 2 inches - based on engravings. These pieces were much in demand amongst the newly emergent middle class and collectors. Baroque art historian and artist Joachim von Sandrart coined the term "Little Masters", based on the collective's preference for miniaturism, in the seventeenth century. Artist and engraver Sebald Beham led the group, which also included his brother Barthel Beham, Georg Pencz, and Heinrich Aldegrever. The Beham brothers and Pencz grew up in Nuremburg and were influenced by Albrecht Dürer, but were banished from the majority-Catholic city in 1525 for their adherence to Lutheranism.

Although Dürer influenced the group, according to the Getty, his own small prints, depicting Biblical and mythological scenes, varied by specializing "in optical effects of light and shadow. Slim, elongated figures and agitated drapery further distinguish his work."

Though the work of the Little Masters included religious subjects, their prints often depicted scenes of peasant life or classical myth incorporating erotic elements. Genre scenes, such as Sebald Beham's series Peasant Festival (1537) were very influential. As art historians Peter van der Coelen and Friso Lammertse note: Sebald Beham "played a pioneering role in the theme of the peasant celebration." His "January and February" print from 1546's Peasant Festival, for example, depicts two peasant-couples dancing in a Bruegel-esque manner, the first representing the month of January and the second February.

Despite their name, some of the artists associated with the Little Masters also created large prints that were similarly influential. As van der Coelen and Lammertse add, "Beham left his mark on the history of genre art, not just with small engravings of dancing peasants but also with some large woodcuts, of which the Large Village Fair of 1535 is the most impressive. This monumental print depicts a view of a village at kermis time, with people eating, drinking, playing, and fighting. It is the earliest work of its kind, anticipating the kermisses of Peeter van der Borcht and Pieter Bruegel."

The Weser Renaissance

German art historian Richard Klapheck first coined the term "Weser Renaissance", to define a type of architecture found around the River Weser and the surrounding area, in 1912. Weser Renaissance buildings were distinctive in their use of bossage stone - rustic or uncut stone which could be carved after being laid in place - decorated window gables and facades, as well as double windows and alcoves. The term became internationally recognized through American art historian Henry Russell Hitchcock's German Renaissance Architecture (1981), which emphasized the style's social and historical context.

The Weser Renaissance style has often has been connected to German nationalism and fascism. Jürgen Soenke, a Nazi official in charge of the "Speeches of the Führer" and the PPK, or Protection of National Socialist Literature, became an art historian in later life and popularized the term "Weser Renaissance in his 1964 book Die Weserrenaissance, which ran to many editions. In it, he ascribed the style's popularity to the fact that it came "from the people [and] is a folk art." As a result, many critics and institutions, including the Weser Renaissance Museum, have advised caution in using the term.

One figure generally seen as a pioneer of the Weser Renaissance is Jörg Unkair, known as The Master of Tübingen. Unkair was appointed to build Stadthagen Castle (1535-39), one of the oldest and most influential buildings associated with the style. Intended as a residence for the Counts of Schaumburg, the building consists of wings surrounding an inner courtyard. Fashioned from local sandstone, the structure's stepped semicircular gables, decorated façade, and double windows pioneered the features that would come to define the architecture of the region.

Unkair was primarily influenced by Venetian Renaissance architecture, which he melded with elements of late Gothic. In a practical and economic level, his success reflected an increase in agricultural trade along the Weser River, combined with the increased wealth of local German nobles who had fought as mercenaries in the era's religious wars. Many aristocrats wanted to convert their castles into palaces by building wings to enclose courtyards, with towers at each corner.

The lesser nobility and wealthy members of the merchant class also adopted Weser style, as did city councils for civic building projects. Bremen Town Hall, built in 1400 in the Gothic style, was transformed in the Weser Renaissance manner from 1609 to 1612, as shown by the alcoves that line the lower level and its stepped ornamented gables. In 2004, naming the hall a World Heritage site, UNESCO wrote that it "represents the medieval Saalgeschossbau-type of hall construction, as well as being an outstanding example of the so-called Weser Renaissance in Northern Germany."

Following Unkair's death in 1553, Cord Tönnis succeeded him as master builder of Detmold Castle (1553-57) and went on to become a leading architect based in Hamelin, known from structures such as the Leisthaus, a famous town-house in the city (1597). Another important figure, Paul Francke, began his career by transforming the medieval Hesse Castle into the palace residence of Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, in 1665. Subsequently appointed as director of all the Duchy's construction projects, Francke oversaw the construction and reconstruction of abbey churches, castles and their fortifications, and university buildings. One of his most famous designs is the Juleum Novum (1592-1612) the auditorium of the University of Helmstedt.

The Weser Renaissance went through several stages of evolution. In the 1560s Dutch influence became more prevalent, as seen by the use of the Dutch gable, using a volute (a spiral scroll design) derived from Italian Renaissance architecture. Half-timbered buildings, built of bricks placed in a wooden structures so that the wood was still visible, became popular during the early 1600s. Examples of this style include The Pied Piper House (1602) in Hamelin, Tönnis's home-town, which has been described as a jewel of Weser Renaissance architecture. The town center includes other noted structures such as The Wedding House (1610-17), although the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618 brought an end to much of the era's architectural innovation.

Later Developments - After German Renaissance

The origins of the Christian Reformation are many and various, but a vital date in its emergence is October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses, demanding reforms of the Catholic Church, to the church-door in Wittenburg. An age of conflict followed, marked by wars, persecution, attacks on dissenting Christians and Jewish communities, witch trials, and executions. German painting and art declined as a result. Reflecting the Protestant association between visual art and idolatry, Lucas Cranach the Elder's work became much more limited in thematic scope, increasingly focusing on depictions of Martin Luther and other leaders of the Reformation.

In the upheaval, both the church and the aristocracy no longer commissioned works of art. It is thought that Hans Holbein, one of the few Renaissance masters who lived to the mid-1500s, relocated to England in 1532 because of the increasing hostility to painting in Germany. Though England was also part of the Reformation, with Henry VIII breaking from the Catholic Church to form the Church of England, Holbein found a more congenial environment in the country's aristocratic court. Some scholars date the end of the German Renaissance to Holbein's death in 1543. In general, the masterpieces of the first half of the sixteenth century were followed by a dearth of notable works.

Legacy

A number of German Renaissance artists had a long-lasting influence reaching into the modern era. German Renaissance printmaking was a major influence on the nineteenth-century German-Romantic group The Nazarenes, and also on German Expressionism of the early twentieth century. Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst referenced the Isenheim Altarpiece in their works, and this masterwork by Nikolaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald also inspired Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and George Grosz.

Meanwhile, Albrecht Dürer's self-portraits marked the first stirrings of the modern cult of self-portraiture and the artist as exalted auteur, both defining features of modern and contemporary art. In similar vein, the landscapes of Albrecht Altdorfer and the Danube school pointed the way to Romanticism and the works of J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich. In architecture, the ruins of German Renaissance buildings became a noted motif fueling Romanticism's treatments of landscape.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI