Summary of Charles Baudelaire

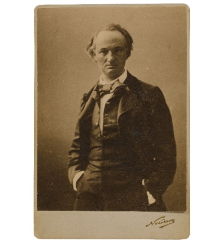

Baudelaire is arguably the most influential French poet of the nineteenth century and a key figure in the timeline of European art history. A denizen of Paris during the years of burgeoning modernity, his writing showed a strong inclination towards experimentation and he identified with fellow travellers in the field of contemporary painting, most notably Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet. A rebel of near-heroic proportions, Baudelaire gained notoriety and public condemnation for writings that dealt with taboo subjects such as sex, death, homosexuality, depression and addiction, while his personal life was blighted with familial acrimony, ill health, and financial misfortune. Despite these hinderances, he managed to leave his indelible stamp on three overlapping idioms: art criticism, poetry, and literary translation. It is in respect of the former that he can be credited with providing the philosophical connection between the ages of French Romanticism, Impressionism and the birth of what is now considered modern art.

Accomplishments

- Baudelaire saw himself as the literary equal of the contemporary artist; especially Delacroix with whom he felt a special affinity. Like Delacroix, Baudelaire was committed to testing the limits of his art in the way he sought to capture the vicissitudes of human emotions. Where Baudelaire used poetry to achieve this affect, Delacroix used color, but both men were leading a charge towards a new - modern - era in art history.

- Baudelaire's name is inextricably linked with the idea of the flâneur: the anonymous street wanderer who created a poetic record of the rapidly shifting environment to which he, and his fellow urban dwellers, were exposed. As a "man of the city", he wandered anonymously throughout the streets, embankments, and arcades of Paris observing the behaviour of crowds in this new age of window shopping and cafe culture. The concept of the flâneur became an important phenomenon for future artists and, after the writings of the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin which introduced Baudelaire to a new twentieth century audience, for the academic development of the cultural studies too.

- Baudelaire played a significant part in defining the role both of the artist and the art critic. In his call for a more modern (more relevant) art style, Baudelaire argued that artists like Delacroix and Manet offered the best step forward in that direction. But he also helped viewers see the importance of the Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David, appreciate the talents of lesser-known artists such as the illustrator Constantin Guys and the etcher Charles Meryon, all of whom captured something of the fleeting mood of their times.

- Baudelaire became a close friend of Manet on whom he had a profound influence. Indeed, it was through Baudelaire's encouragement that Manet - a kindred spirit who was reviled for his painting Olympia just as much as Baudelaire had been reviled for his collection Les Fleurs du Mal - ultimately fulfilled Baudelaire's vision of the true painter of modern life; one who could capture the transient quality of modern Paris with a new picture perspective and energized color palette.

The Life of Charles Baudelaire

The original flâneur, Baudelaire was an invisible idler; the first connoisseur of the streets of modern Paris. "I walk alone", he wrote, "absorbed in my fantastic play [...] Tripping on words, as on rough paving in the street, Or bumping into verses I long had dreamed to meet".

Charles Baudelaire and Important Artists and Artworks

The Death of Marat (1793)

Arguably Jacques-Louis David's greatest painting, The Death of Marat, features the French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat at the moment of his death. He often worked at a makeshift desk while in his bathtub to help alleviate irritation from his chronic skin condition and it is here that he was assassinated by the federalist revolutionary C harlotte Corday. Beautifully awash in light, in this painting his white skin stands in sharp contrast to the dark background and his limp body evokes similarities to Christ's body at the time of his deposition from the cross.

A champion of Neoclassicism, Charles Baudelaire praised this painting in an article about the movement in the journal Le Corsaire-Satan in 1846. His adoration of the painting offers proof of Baudelaire's willingness to challenge public opinion. According to author Frederick William John Hemmings, at the time of publication, political public opinion was not in favor of the Revolution and so, "in praising [the painting] Baudelaire was well aware that he was flying in the face of received opinion. Today, of course, the unpopular view he put forward is the generally accepted one ".

This painting saw the writer begin to embrace modernity. Of the painting specifically, he wrote, "the drama has been caught, still living in all its lamentable horror, and by a strange feat that makes of this painting David's true masterpiece and one of the great curiosities of modern art, it has nothing trivial or ignoble about it". In describing its impact, Baudelaire added, "there is something in this work that melts the heart and wrings it too; in the chilly air of this chamber, on these cold walls, around this cold bath-tub is also a coffin, there hovers a soul". David's depiction surely spoke to the radical spirit in Baudelaire.

Oil on canvas - Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium

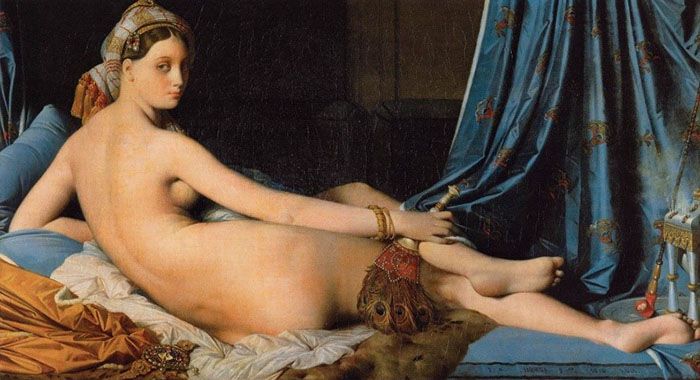

Grande Odalisque (1814)

A nude woman, but for the colorful scarf in her hair and bracelets on her wrist, dominates the canvas of Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres's Grande Odalisque. As the title indicates, she is a harem girl who lounges across cushions and colorful sheets in her bedroom in which also hangs a blue brocade curtain in an exotic pattern. The model is a study in contradictions in that her nudity and her direct gaze, looking back over her right shoulder, make her actions seem at once demure and bold. A controversial work, it was the subject of much debate when it first debuted at the Paris Salon of 1819. According to art historian François De Vergnette, "the nude was a major theme in Western art, but since the Renaissance figures portrayed in that way had been drawn from mythology; here [however] Ingres transposed the theme to a distant land". Ingres's willingness to push for a more modern form made him an artist worthy of analytical scrutiny for Baudelaire.

Today this work is considered a precursor to the Romantic movement. According to the art historian Rosemary Lloyd, Baudelaire believed that Romanticism was the "expression of beauty, springing from a sharp awareness of what the modern world has to offer that makes its forms of beauty unique". Baudelaire was especially impressed with any artist who could master the art of portraiture and depictions of human figures. Of the art of portraiture, he stated, "here the art is more difficult because it is more ambitious. You have to be able to bathe a head in the gentle vapours of a hot atmosphere or make it rise from the depths of dusk". According to Lloyd, Baudelaire considered Ingres to be, "'the master of line' and here in this work he shows his mastery over the human figure while simultaneously rendering it in a modern way".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Louvre, Paris, France

28 July: Liberty Leading the People (1830)

In July 1830, "the People" of Paris embarked on a bloody revolt against the country's dictatorial monarch, King Charles X. On completing his commemoration of this momentous historic event Delacroix wrote to his brother stating: "I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her". The resulting painting was an archetype of Romanticism; destined to become one of France's finest art treasures, and Delacroix's greatest masterpiece. The artist's blend of classical allegory - "Liberty" as immortal and untouchable goddess brandishing the tricolour and leading her subjects into battle - with blunt realism - "Liberty" is dishevelled and flushed of face as she stands atop the bodies of the injured and dying - was brought to life by Delacroix through loose brush strokes and vivid coloring.

Baudelaire was Delacroix's most vocal supporter, describing him as "decidedly the most original painter of all times, ancient and modern" while adding that "everything in his oeuvre is desolation [...] smoking, burning cities, raped women, children thrown under the hooves of horses or stabbed by delirious mothers". Yet for all the artist's thematic preferences, Baudelaire was equally absorbed by Delacroix's handling of color since this illustrated perfectly the "correspondences" between the poet and the painter. While the poet was challenged in their ability to describe colors, the painter was equally curtailed in their ability to capture non-visual emotions and sounds. Baudelaire's higher appreciation of Delacroix was based on the idea that a Romantic painter of Delacroix's standing was the supreme colorist who could use his palette to capture and convey non-visual sensations. Color, in other words, could, if applied with great skill and verve, bring about a higher "poetic" state of bliss in the viewer.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Louvre, Paris, France

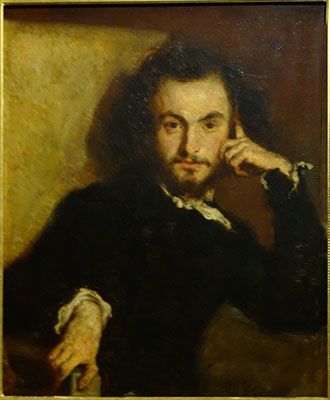

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire (1844)

Émile Deroy's portrait of Baudelaire shows his sitter staring directly out at the viewer; his left hand resting and one finger extended pressing on the side of his head. According to author Frederick William John Hemmings, Deroy painted his portrait "in four sittings in the reception room of his apartment, at night and by lamplight, with Nadar and three other artist friends looking on and making suggestions [...] This is Baudelaire posing as Mephistopheles, with his carefully trimmed beard and moustache and the thick black eyebrows of which one is slightly raised to give a quizzical, sardonic look as he gazes straight at the spectator".

Deroy played an important role in Baudelaire's life. According to Hemmings it was "thanks to Deroy [that] Baudelaire was able to visit the studios of painters and sculptors in the neighbourhood and engage them in talk, imbibing in this way much of the technical information put to good use in his later writings on art. Indeed, Deroy introduced Baudelaire to the Café Tabourey where he was "able to meet and listen to some of the leading art critics of the day". According to Hemmings, Deroy was angry that his portrait was not being accepted into the Paris Salon of 1846. This did not deter Baudelaire from treasuring it for many years. Sadly, Deroy died only two years after completing his heroic portrait of his friend.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musée national du château de Versailles, Versailles, France

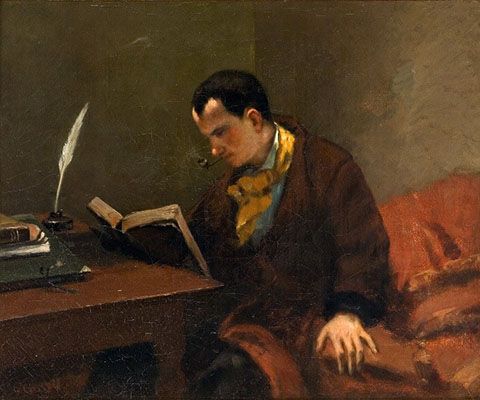

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire (1847)

In Gustave Courbet's portrait, Baudelaire is pictured with the tools of his trade. He is reading a book (perhaps reviewing something he has just written) his feather quill and ink stand await his attention on the table at which he sits. Bedecked in a brown coat and yellow neck-scarf, he is placed in the sparse surroundings that convey the reduced financial circumstances in which he lived most of his adult life.

Baudelaire and Courbet were good friends and yet Baudelaire rarely wrote about the artist. Courbet was to Realism what perhaps Delacroix was to Romanticism and the former movement did not conform to Baudelaire's idea of modernism. According to the records of the Musée d'Orsay, since he "considered 'the imagination to be the queen of faculties', Baudelaire could not appreciate Realism". The d'Orsay records how Badelaire referred to Corbet as no more than a "powerful worker" in an August 1855 issue of Le Portefeuille stating further that "the heroic sacrifice that Monsieur Ingres makes for the honour of tradition and Raphaelesque beauty, Courbet accomplishes in the interests of external, positive, immediate nature ". Courbet's portrait speaks most then of the men's mutual respect; a friendship that easily transcended aesthetic and ideological differences of opinion.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France

Pont-Neuf, Paris (1853)

One of a series of etchings of which Paris landmarks are the theme, this etching by Charles Meryon features the Pont-Neuf bridge. According to text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the focus of this work is, "the semicircular stone boutiques lining the bridge, which were actually in the process of being removed when Meryon chose this subject for his print".

Baudelaire liked to write about the artists whose work he most admired and spent a portion of his Salon de 1859 publication focusing on Meryon's city etchings, stating that, "through the harshness, refinement, and sureness of his drawing, M. Meryon recalls the excellent etchers of the past". But it was more than just his technique that Baudelaire admired, writing "I have rarely seen the natural solemnity of a vast city represented with more poetry. The majesty of massed stone, spires 'pointing to the sky', the obelisks of industry vomiting to the firmament their accumulations of smoke, the prodigious scaffolding of monuments under repair, applying to the solid body of the architecture their own open-work architecture with its highly paradoxical beauty, the turbulent sky, freighted with rage and rancor, the depth of perspectives increased by the thought of all the drams that have unfolded within them, none of the complex elements that make up the grim and glorious decour of civilization has been forgotten". For a man who loved Paris and loved the idea of modernity as Baudelaire did, Meryon's image, which effectively captured their city in a state transition, served as the visual embodiment of the poet's own heartfelt views of the fleeting qualities of the age.

Etching and drypoint - Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Boy with Cherries (1859)

Manet's realist portrait shows a young blond-haired boy leaning on a stone wall cupping a bowl of cherries. Manet's control of composition is revealed here through his use of vivid red color which matches the boy's cap with the fruit. That he is happy is abundantly evident in his sweet smile, yet there is a terribly sad irony behind the painting. The subject of this painting is a boy named Alexandre who had, in Baudelaire's words, an "intemperate taste for sugar and brandy", and was given to bouts of melancholy. Coming from a poor family living near the artist's studio, Manet used the boy as a model for several paintings and he earned extra pocket money from the artist by doing chores around Manet's studio. But this painting was especially personal to Manet who only completed it after discovering the boy's hanged body in his studio.

A friend of Manet's, Baudelaire had heard of this tragedy and memorialized the incident in one of his last prose poems, La Corde (The Rope) (1864). The poem is dedicated "To Édouard Manet" and is written from the artist's perspective. In Baudelaire's somewhat misanthropic re-telling of events Manet visits Alexandre's mother to inform her of the tragedy. She duly accompanies Manet to his studio where the artist notices "with a disgust born of horror and anger, that the nail had remained fixed in the wall with a long piece of rope still trailing from it". The boy's mother implores Manet "Oh, sir! Let me have it! Please! I beg you!" leaving the artist to surmise that the incident had "so distressed her" that she wanted to keep the rope "as a horrible and cherished relic" of her son's death. However, according to local superstition, rope of a hanged person brings luck and Alexandre's mother plans to sell pieces of the rope to her neighbours: "And so, suddenly, a light came on in my mind, and I understood why the mother had insisted on ripping the rope from my hand and the commerce with which she meant to console herself".

It is easy to read an element of cynicism towards the callous mores of commerce in Baudelaire's tale but more telling is the introduction to his poem which can be read of a thinly veiled reproach of Baudelaire's own mother whom (it seems) he never forgave for abandoning him for his stepfather: "It is as difficult to imagine a mother without motherly love as light without heat; is it not thus perfectly legitimate to attribute to motherly love all of a mother's actions and thoughts pertaining to her child? And yet, listen to this little story, where I was singularly mystified by the most natural illusion".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal

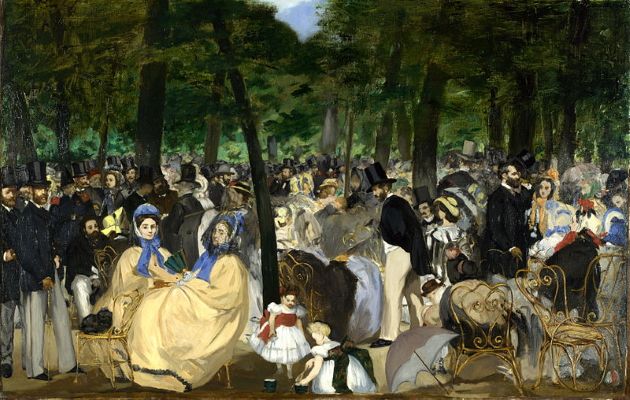

Music in the Tuileries Gardens (1862)

Manet's landmark painting shows a selection of characters from Parisian bohemian society, and Manet's own family, gathered for an open-air afternoon concert. It caused uproar when first exhibited in 1863, drawing criticism for its unfinished surface and unbalanced composition (such as the tree in the foreground which dissects the picture plane). The "crude" modern subject matter did not sit well with the Parisian art establishment either. Indeed, urban scenes would not be considered suitable subject matter for serious artists for another decade or so.

Although the illustrator Constantin Guys emerged as the main protagonist in Baudelaire's "Le Peintre de la vie moderne" ("The Painter of Modern Life") in reality it was Manet who rose to the challenges laid down by the poet. According to Baudelaire, the artist who wishes to truly capture the bustle and buzz of this new Parisian society must first adopt the role of the flâneur; a man at once a part of, and removed from, the crowd (and by placing himself in the far left of his crowd Manet would seem to self-consciously identify with the figure of the flâneur). For Baudelaire, moreover, modernity was all about "the transient, the fleeting, the contingent" and the "painter of modern life" must be one who is capable of capturing this spirit through a shorthand style of loose brush work and lucid coloring.

There is a spontaneity to Manet's painting that captures the fleeting expressions and mannerisms of individuals in his crowd. The lack of order to the painting - some figures are more defined than others and colors and shapes lose clarity as they merge into the background - conforms to Baudelaire's idea of the "contingent" and thereby offered a new painterly perspective that was at once focused and impressionable. Though it is thought that Manet used photographic portraits as a visual aid when composing his painting in the studio, his painting achieved what the new technology could not: the fleeting passages of time.

Oil on canvas - National Galley, London

Biography of Charles Baudelaire

Childhood and Education

In his later years, Baudelaire was given to describe his family as a disturbed cast of characters, claiming that he was descended from a long line of "idiots or madmen, living in gloomy apartments, all of them victims of terrible passions". Though there was no indication of how literally one should treat his claims, it is true that he had a troubled family life. He was the only son born to parents François Baudelaire and Caroline Defayis; although his father (a high ranking civil servant, and former priest), had a son (Alphonse) from a previous marriage. Baudelaire's stepbrother was sixteen years his senior while there was a thirty-four-year age difference between his parents (his father was sixty and his mother twenty-six when they married).

Baudelaire was just six years old when his father died. Nevertheless, François Baudelaire can take credit for providing the impetus for his son's passion for art. An amateur artist himself, François had filled the family home with hundreds of paintings and sculptures. Baudelaire's mother was not an art lover, however, and she took a particular disliking to her husband's more salacious pieces. According to author F. W. J. Hemmings, Caroline was "prudish enough to feel some embarrassment at being perpetually surrounded by images of naked nymphs and lusty satyrs, which she quietly removed one by one, replacing them by other less indecent pictures stored in the attics ". François died in February 1827, and Baudelaire lived with his mother in a Paris suburb for a period of eighteen months. Recalling in adulthood this blissful time alone with his mother, Baudelaire wrote to her: "I was forever alive in you; you were solely and completely mine".

Baudelaire's period of personal bliss was short lived, however, and in November 1828, his beloved mother married a military captain named Jacques Aupick (Baudelaire later lamenting: "when a woman has a son like me [...] she doesn't get married again"). His stepfather rose through the ranks to General (he would later become French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire and Spain and Senator under the Second Empire under Napoleon III) and was posted to Lyon in 1831. On their arrival in Lyon, Baudelaire became a boarding student at the Collège Royal. This event was a sign of the ambivalent relationship Baudelaire shared with the "stubborn", "misguided" yet "well intentioned" Aupick: "I can't think of schools without a twinge of pain, any more than of the fear my stepfather filled me with. Yet I loved him", he wrote in later life.

Baudelaire transferred to the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand on the family's return to Paris in 1836. It was here that he began to develop his talent for poetry, though his masters were troubled by the content of some of his writings ("affectations unsuited to his age" as one master commented). Baudelaire was also given to bouts of melancholia and insubordination, the latter leading to his expulsion in April 1839. Baudelaire's parents quickly enrolled him in the Collége Saint-Louis where he successfully passed his baccalauréat exam by August 1839.

Early Training

On completing school, Aupick encouraged Baudelaire to enter military service. His decision to pursue a life as a writer caused further family frictions with his mother recalling: "if Charles had accepted the guidance of his stepfather, his career would have been very different. He would not have won himself a name in literature, it is true, but we should have been all three much happier". Baudelaire pursued his literary aspirations in earnest but, in order to appease his parents, he agreed to enrol as a "nominal" (non-attending) law student at the École de Droit.

Taking up residence in Paris's Latin Quarter, Baudelaire embarked on a life of promiscuity and social self-indulgence. He sexual encounters (including those with a prostitute, affectionately nicknamed "Squint-Eyed Sarah", who became the subject of some of his most candid and touching early poems) led him to contract syphilis. The venereal disease would lead ultimately to his death but he did not let it dent his bohemian lifestyle which he indulged in with a circle of friends including the poet Gustave Le Vavasseur and the author Ernest Prarond.

Living the life of a bohemian dandy (Baudelaire had cultivated quite the reputation as a unique and elegant dresser) was not easy to sustain and he amassed significant debts. Baudelaire approached his stepbrother for help but the sibling refused and instead informed his parents of their son's financial predicament. In an attempt to encourage him to take stock, and to separate him from his bad influences, his stepfather sent him on a three-month sea journey to India in June 1841. While the voyage fired his imagination with exotic imagery, it proved a miserable experience for Baudelaire who, according to biographer F. W. J. Hemmings, developed a stomach problem which he tried (unsuccessfully) to cure "by lying on his stomach with his buttocks exposed to the equatorial sun [and] with the inevitable result that for some time afterwards he found it impossible to sit down ". Having reached Mauritius, Baudelaire "jumped ship" and, after a short stay there, and then on the island of Reunion, he boarded a homebound ship that docked in France in February 1842.

Mature Period

Baudelaire finally gained financial independence from his parents in April 1842 when he came into his inheritance. Flush with funds, he rented an apartment at the Hôtel Pimodan on the Île Saint-Louis and began to write and give public recitations of his poetry. His inheritance would have supported an individual who conducted their financial concerns with prudence, but this did not fit the profile of a dandified bohemian and, before very long, his extravagant spending - on clothes, artworks, books, fine dining, wines and even hashish and opium - had seen him squander half his fortune in just two years. He had also succumbed to the tricks of fraudsters and unscrupulous moneylenders. So concerned were they about their son's predicament, Baudelaire's parents took legal control of his inheritance, restricting him to only a modest monthly stipend. This was insufficient to cover his debts, however, and he became financially dependent on his parents once more. This situation infuriated Baudelaire whose reduced circumstances led to him being forced (amongst other things) to move out of his beloved apartment. He fell into a deep depression and in June of 1845 he attempted suicide.

Baudelaire had met Jeanne Duval soon after his return from his ill-fated voyage to the South Seas. She was his lover and then, after the mid-1850s, his financial manager too. Duval would come in and out of his life for the rest of his years, and inspired some of Baudelaire's most personal and romantic poetry (including "La Chevelure" ("The Head of Hair")). Baudelaire's mother disapproved of the fact that her son's muse was a poor, racially-blended, actress and his connection with her further tested their already strained relationship. Despite his various woes, Baudelaire was also developing his unique writing style; a style where, as Hemmings described it, "much of the work of composition was done out of doors [and] in the course of solitary walks round the streets or along the embankments of the Seine".

As part of his recovery from his suicide attempt, Baudelaire had turned his hand to writing art criticism. He was a committed art lover - he spent some of his inheritance on artworks (including a print of Delacroix's Women of Algiers in their Apartment) and was a close friend of Émile Deroy who took him on studio visits and introducing him to many in his circle of friends - but had received next-to-no formal education in art history. According to Hemmings, his knowledge of art had been based on no more than "frequent visits to art galleries, beginning with a school trip in 1838 to view the royal collection at Versailles, and the knowledge of art history he had picked up from his reading" (and, no doubt, from the bohemian social circles in which he moved). His first published art criticism, which came in the shape of reviews for the Salons of 1845 and 1846 (and later in 1859), effectively introduced the name of "Charles Baudelaire" to the cultural milieu of mid-nineteenth century Paris.

Baudelaire was a champion of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, the latter being, in his view, the bridge between the best of the past and the present. He was especially enraptured by the paintings of Eugène Delacroix (he soon made the personal acquaintance of the artist who inspired his poem Les Phares) and through him, and through praise for others such as Constantin Guys, Jacques-Louis David and Édouard Manet he offered a philosophy on painting that prescribed that modern art (if it was to warrant that accolade) should celebrate the "heroism of modern life". He further prescribed that the "true painter" would be one who "proves himself capable of distilling the epic qualities of contemporary life, and of showing us and making us understand, by his colouring and draughtsmanship, how great we are, how poetic we are, in our cravats and our polished boots". Baudelaire also supplied a suggestion of what the role of the art critic should be: "[to] provide the untutored art lover with a useful guide to help develop his own feeling for art " and to demand of a truly modern artist "a fresh, honest expression of his temperament, assisted by whatever aid his mastery of technique can give him".

Baudelaire saw himself very much as the literary equal of the modern artist and in January 1847 published a novella entitled La Fanfarlo which drew the analogy with a modern painter's self-portrait. It was also at this time that he became involved in the riots that overthrew King Louis-Philippe in 1848. To begin with, he, and friends including Gustave Courbet, stood by and observed as the riots unfolded. But rather than remain a sympathetic observer, Baudelaire joined the rebels.

He had shown no radical political allegiances hitherto (if anything had been more sympathetic towards the interests of the petit-bourgeois class in which he had been born) and many in his circle were taken aback by his actions.

It is possible (likely even) that his actions were an attempt to anger his family; especially his stepfather who was a symbol of the French establishment (some unsubstantiated accounts suggest Baudelaire was seen brandishing a musket and urging insurgents to "shoot general Aupick"). As the riots were quickly put down by King Charles X, Baudelaire was once more absorbed by his literary pursuits and in 1848 he co-founded a news-sheet entitled Le Salut Public. Though funds only allowed for two issues it helped raise Baudelaire's creative profile. Baudelaire also took an active part in the resistance to the Bonapartist military coup in December 1851 but declared soon after that his involvement in political matters was over and he would, henceforward, devote all his intellectual passions to his writings.

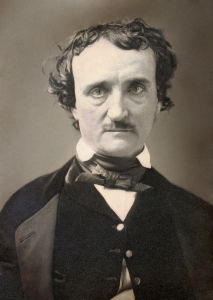

Between 1848 and 1865 Baudelaire undertook one of his most important projects, the French translation of the complete works of Edgar Allan Poe. More so than his art criticism and his poetry, his translations would provide Baudelaire with the most reliable source of income throughout his career (his other notable translation came in 1860 through the conversion of the English essayist Thomas De Quincey's "Confessions of an English Opium-Eater"). Baudelaire, who felt a near-spiritual affinity with the author - "I have discovered an American author who has aroused my sympathetic interest to an incredible degree" he wrote - provided a critical introduction to each of the translated works. Indeed, Baudelaire's friend and fellow author Armand Fraisse, stated that he "identified so thoroughly with [Poe] that, as one turns the pages, it is just like reading an original work". Though Baudelaire almost single-handedly introduced Poe to the French speaking public, his translations would attract controversy with some critics accusing the Frenchman of taking some of the American's words to use in his own poems. Though these allegations proved unfounded, it is widely accepted that through his interest in Poe (and, indeed, the theorist Joseph de Maistre whose writing he also admired) Baudelaire's own worldview became increasingly misanthropic.

Despite his growing reputation as an art critic and translator - a success that would smooth the path to the publication of his poetry - financial struggles continued to plague the profligate Baudelaire. According to Hemmings, between 1847 and 1856 things became so bad for the writer that he was, "homeless, cold, starving, and in rags for much of the time". His mother tried periodically to return to her son's good graces but she was unable to accept that he was still, despite his obsession with the society courtesan Apollonie Sabaier (a new muse to whom he addressed several poems) and, later still, a passing affair with the actress Marie Daubrun, involved with his mistress Jeanne Duval.

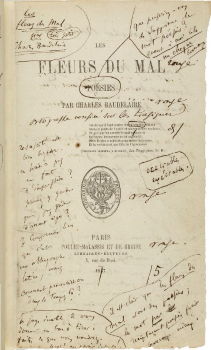

Baudelaire's reputation as a rebel poet was confirmed in June 1857 with the publication of his masterpiece Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil). Although an anthology, Baudelaire insisted that the individual poems only achieved their full meaning when read in relation to one another; as part of a "singular framework" as he put it. In addition to its shifting views of romantic and physical love, the collected pieces covered Baudelaire's views on art, beauty, and the idea of the artist as martyr, visionary, pariah and/or even fool.

Now considered a landmark in French literary history, it met with controversy on publication when a selection of 13 (from 100) poems were denounced by the press as pornographic. On July 7, 1857 the Ministry of the Interior arranged for a case to be brought before the public prosecutor on charges relating to public morality. Unsold copies of the book were seized and a trial was held on the 20th of August when six of the poems were found to be indecent. As well as the demand to remove the offending entries, Baudelaire received a fine of 50 francs (reduced on appeal from 300 francs). Disgusted by the court's decision, Baudelaire refused to let his publisher remove the poems and instead wrote 20-or-so new poems to be included in a revised extended edition published in 1861. (The banned six poems were later republished in Belgium in 1866 in the collection Les Épaves (Wreckage) with the official French ban on the original edition not lifted until 1949.)

Baudelaire seemed unable to comprehend the controversy his publication had aroused: "no one, including myself, could suppose that a book imbued with such an evident and ardent spirituality [...] could be made the object of a prosecution, or rather could have given rise to misunderstanding" he wrote. Professor André Guyaux describes how the trial, "was not due to the sudden displeasure of a few magistrates. It was the result of an orchestrated press campaign denouncing a 'sick' book [and even] though Baudelaire achieved rapid fame, all those who refused to acknowledge his genius considered him to be dangerous. And there were quite a few". This trial, and the controversy surrounding it, made Baudelaire a household name in France but it also prevented him from achieving commercial success.

The weight of the trial, his poor living conditions, and a lack of money weighed heavily on Baudelaire and he sunk once more into depression. His physical health was also beginning to seriously decline due to developing complications with syphilis. He started to take a morphine-based tincture (laudanum) which led in turn to an opium dependency. According to Hemmings, "from 1856 onwards, the venereal infection, alcoholic excess and opium addiction were working in an unholy alliance to push Baudelaire down to an early grave". Things with his family did not improve either. Even after his stepfather's death in April 1857, he and his mother were unable to properly reconcile because of the disgrace she felt at him being publicly denounced as a pornographer.

Later Period

Baudelaire and Manet formed a friendship that proved to be one of the most significant in the history of art; the painter realizing at last the poet's vision of converting Romanticism to Modernismmodernism. The two men became personally acquainted in 1862 after Manet had painted a portrait of Baudelaire's (on/off) mistress Jeanne Duval. It is thought that the artist intended his portrait to be a viewed specifically by Baudelaire in recognition of the positive notice the writer had given him in his recently published essay "L'eau-forte est â la mode" ("Etching is in Fashion").

Having bonded, the two friends would stroll together in the grounds of the Tuileries Gardens where Baudelaire observed Manet complete several etchings. Baudelaire convinced his friend to be brave; to ignore academic rules by using an "abbreviated" painting style that used light brush strokes to capture the transient atmosphere of frivolous urban life. Indeed, it was on Baudelaire's recommendation that Manet painted the canonical Music in the Tuileries Gardens (1862). Cited by many as the first truly modernist painting, Manet's image captures a "glimpse" of everyday Parisian life as a fashionable crowd gathers in the Gardens to listen to an open-air concert. The painting was so topical it featured a cast of the artist's own family and personal acquaintances including Baudelaire, Théophile Gautier, Henri Fantin-Latour, Jacques Offenbach and Manet's brother Eugène. Manet himself also features as an onlooker in a gesture that alludes to the idea of the flâneur as an agent of the age of modernity.

It was during the same period that Baudelaire abandoned his commitment to verse in favor of the prose poem; or what Baudelaire called the "non-metrical compositions poem". Though precedents can be found in the poetry of the German Friedrich Hölderlin and the French Louis Bertrand, Baudelaire is widely credited as being the first to give "prose poetry" its name since it was he who most flagrantly disobeyed the aesthetic conventions of the verse (or "metrical") method. Structured on a tension between critical writing and the patterns of verse, the prose poems accommodate symbolism, metaphors, incongruities and contradictions and Baudelaire published a selection of 20 prose poems in La Presse in 1862, followed by a further six, titled Le Spleen de Paris, in Le Figaro magazine two years later. One of his final prose poems, La Corde (The Rope) (1864), was dedicated to Manet's portrait Boy with Cherries (1859).

While Manet and Baudelaire had by now become close friends, it was the draftsman Constantin Guys who emerged as Baudelaire's hero in his 1863 essay, "Le Peintre de la vie moderne" ("The Painter of Modern Life"). The essay amounted to a formal and thematic blueprint of the Impressionism movement nearly a decade before that school came to dominate the avant-garde. There was no little irony in Baudelaire's focus on the little-known Guys given that it was Manet who emerged as the leading light in the development of Impressionism. According to the art historian Alan Bowness it was in fact Baudelaire's friendship "that gave Manet the encouragement to plunge into the unknown to find the new, and in doing so to become the true painter of modern life".

In the last years of his life, Baudelaire fell into a deep depression and once more contemplated suicide. He attempted to improve his state of mind (and earn money) by giving readings and lectures, and in April 1864 he left Paris for an extended stay in Brussels. He had hoped to persuade a Belgium publisher to print his compete works but his fortunes failed to improve and he was left feeling deeply embittered. Indeed, in a letter to Manet he urged his friend to "never believe what you may hear about the good nature of the Belgians". Baudelaire and Manet were in fact kindred spirits with the painter receiving the same sort of critical backlash for Olympia (following its first showing at the Paris Salon of 1865) as Baudelaire had for Les Fleurs du Mal. Manet wrote to Baudelaire telling him of his despair over Olympia's reception and Baudelaire rallied behind him, though not with soothing platitudes so much as with his own inimitable brand of reassurance: "do you think you are the first man placed in this situation?", he wrote, "Is yours a greater talent than Chateaubriand's and Wagner's? They too were derided. It did not kill them".

In the summer of 1866 Baudelaire, stricken down by paralysis and aphasia, collapsed in the Church of Saint-Loup at Namur. His mother collected her son from Brussels and took him back to Paris where he was admitted to a nursing home. He never left the home and died there the following year aged just 46.

The Legacy of Charles Baudelaire

Many of Baudelaire's writings were unpublished or out of print at the time of his death but his reputation as a poet was already secure with Stephane Mallarmé, Paul Valaine and Arthur Rimbaud all citing him as an influence. Moving into the twentieth century, literary luminaries as wide ranging as Jean-Paul Sartre, Robert Lowell and Seamus Heaney have acclaimed his writing. His influence on the modern art world was quick to take effect too; not just with Manet and the Impressionist, but also with future members of the Symbolism movement (several of whom attended his funeral) who had already declared themselves devotees. His prose poetry, so rich in metaphor, would also directly inspire the Surrealists with André Breton lauding Baudelaire in Le Surréalisme et La Peinture as a champion "of the imagination".

Baudelaire's contribution to the age of modernity was profound. As professor André Guyaux observed, he was "obsessed with the idea of modernity [and in fact] gave the word its full meaning". But no single figure did more to cement Baudelaire's legend than the influential German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin whose collected essays on Baudelaire, The Writer of Modern Life, claimed the Frenchman as a new hero of the modern age and positioned him at the very center of the social and cultural history of mid-to-late nineteenth-century Paris. It was Benjamin who transported Baudelaire's flâneur into the twentieth century, figuring him as an essential component of our understandings of modernity, urbanisation and class alienation.

Influences and Connections

![Theophile Gautier]() Theophile Gautier

Theophile Gautier![Victor Hugo]() Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo- Charles Asselineau

- Gustave Le Vavasseur

- Gérard de Nerval

-

![Gustave Courbet]() Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet -

![Eugène Delacroix]() Eugène Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix -

![Édouard Manet]() Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet - Emile Deroy

- Constantin Guys

![Theophile Gautier]() Theophile Gautier

Theophile Gautier![Edgar Allan Poe]() Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe- Charles Asselineau

- Gérard de Nerval

- Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve

Useful Resources on Charles Baudelaire

- Baudelaire the Damned: A BiographyOur PickBy F.W.J. Hemmings

- Charles BaudelaireOur PickBy Rosemary Lloyd

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI