Summary of Eero Saarinen

One New Year's Day at 8 o'clock in the morning, Eero Saarinen arrived at his office, looked around and, seeing only his assistant Kevin Roche, said, "Where the hell is everybody?" Roche then had to remind Saarinen that it was a major holiday. But most people who worked or lived with Eero Saarinen would probably say that was par for the course, as he was a highly ambitious and extremely motivated architect - we might say today that his work gave him "tunnel vision". Saarinen's passion for architecture and design, recognized from a very early age, led him to develop his personal, often sculptural, direction and an adventurous spirit. In a rather brief career, Saarinen's imaginative daring produced an extraordinary set of highly futuristic buildings of virtually every possible type, whose impressive stature and visionary designs mean that they still seem to be ahead of their time and have largely remained unaltered more than a half-century later.

Accomplishments

- Saarinen's works, like the St. Louis Gateway Arch and TWA Terminal, often are very sculptural - a quality likely derived from both his mother's influence and his own brief training in sculpture - and structurally adventurous, defying our expectations of how they must stand up. They also exploit the possibilities of modern materials - particularly concrete - and engineering know-how to the fullest extent.

- Though ostensibly an architect of the International Style, whose mature period coincides with the heyday of the movement, Saarinen's genius lies in his focus on finding unique solutions for each individual commission. Occasionally, as with his GM Technical Center, he could employ the International Style perfectly, but Saarinen is often called a "second-generation" modernist for the way he moved beyond the rigid glass-box aesthetic pioneered by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius.

- Saarinen's buildings, including the Ingalls Ice Rink and CBS Building, tend to resonate with familiar themes within human experience, evoking relationships with structures and environments that may at first be unexpected, but harmonize well with their purposes upon further exploration. Saarinen's keen grasp of history and culture helped him understand the context in which his buildings would be inserted, and the strong connections that they make with their surroundings points to why nearly all of his major buildings have survived nearly unchanged to the present day.

Important Art by Eero Saarinen

General Motors Technical Center, Warren, Michigan, USA

Along with structures such as the Lever House and Seagram Building in New York, the General Motors Technical Center is one of the projects that best exemplifies the new identity of American corporate modernism in the 1950s. Unlike those two skyscrapers, the GM Technical Center consists of a sprawling horizontally-oriented 710-acre campus. Quite astutely, Architectural Forum proclaimed it an "Industrial Versailles" upon its completion in 1956, as the campus exudes the same sense of man's ability to order and partition the landscape to his will with modern technology, just as Versailles exuded the new mastery of landscape and natural space during the era of the Scientific Revolution in the late 1600s. (This sense of order is reflected in the repetitive bays and modular layout of the interiors of individual buildings on the campus.) It likewise signals the vast resources and strength of American corporations as the USA emerged as one of the world's two superpowers during this decade.

The aerial view here shows how the Technical Center's various buildings are neatly arranged on a grid-like layout, in harmony with the employee parking lots, which indicate the triumph of American car culture in the economic boom of the postwar era. The large expanses of water serve several purposes: not only do they beautify the landscape and provide breaks between the buildings, roadways, and open land, but they also practically serve as reservoirs to assist in the event of fire - something that GM was acutely aware of since the largest industrial fire in history occurred inone of its Michigan plants in 1953.

Saarinen took inspiration from the sleek precision of GM's vehicles, placing them literally at the center of the concept for the buildings' interiors, which include large foyers characterized by a minimalist geometric rigor that double as showroom for top-of-the-line new vehicles, whose acute angular and curvilinear forms of their fins, body shapes, and rooflines would have been accented in such spaces. On the exterior, this precision is mirrored by the crisp glass-and-steel boxes that use the same kinds of industrial materials needed for manufacturing cars. Saarinen would employ similar design strategies for his subsequent corporate commissions, thus reinforcing this aesthetic of American postwar modernism.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chapel, Cambridge, USA

The MIT Chapel is part of a pair of structures (the other being the Kresge Auditorium) clustered together on the university's campus that Saarinen designed along with all of the landscaping. It consists of a small, cylindrical brick structure perched above a small surrounding moat. One can see the moat from the inside, where the chapel's only windows, located near the floor at the edges of the cylinder, overlook the water below. The chapel's sculptural, undulating rough brick interior walls, paneled in dark wood at the bottom, modulate the space and artificial light not unlike the irregular surfaces inside a cave, making them seem thicker than they actually are. The rather homely chairs are freely arranged facing an altar at the far end that is placed under a circular skylight, signifying the uplifting descent of heavenly spirits into the space.

Saarinen's design finds its complement in the glimmering Harry Bertoia sculpture suspended from the back rim of the skylight (seen here). The overall spatial effect, layered by the moat, solid walls, and thick ceiling, is one of a calm, serene, enfolding sanctuary, a welcome shelter from the vicissitudes of human existence in a complicated modern world. On the exterior, a separate abstract curved metal spire rises above the skylight, thereby underscoring the building's modern sculptural character and its function as a spiritual bulwark.

Saarinen's design arguably also shows a particularly Scandinavian sensitivity that he brought to the commission, possibly prompted by the chapel's location in New England, which like his home state of Michigan is one of the coldest regions of the continental United States. The interior of the MIT Chapel echoes the kind of quiet, serene brick-enclosed modern assembly spaces created in Finland by Saarinen's compatriot Alvar Aalto at nearly the same time, which welcome warmth and comfort needed during the snowy Scandinavian winters, appropriate for promoting a reassuring sense of community. Thus Saarinen's chapel demonstrates his mastery of designing intimate spiritual spaces along with massive projects like the Gateway Arch and the GM Technical Center, and his great airport terminals at JFK and Dulles.

J. Irwin Miller House, Columbus, Indiana, USA

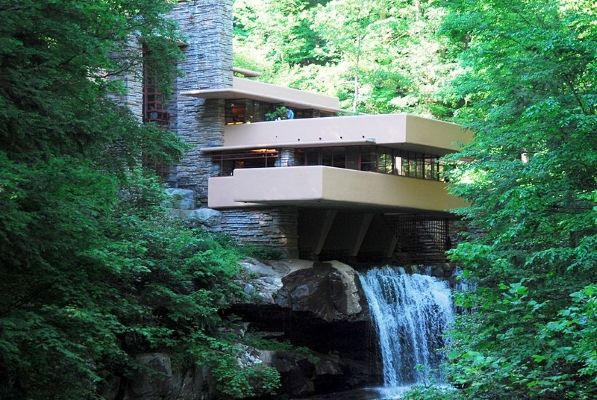

Saarinen rarely designed residences during his mature career, yet the Miller House, built for a corporate scion in the architecturally prominent small town of Columbus, is the best example of these. It resembles the stark aesthetic of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for some of his famous midcentury houses, including the walls of stone and large curtain-wall expanses of glass, and it uses the geometric clarity of the square for the overall form and organization.

Unlike Mies' work, or the residences designed by other great modernists like Richard Neutra or R.M. Schindler, which tend to be asymmetrical, the Miller House's four wings of private spaces branch off of the open living room at the center, similar to a Greek-cross layout. This is unusual for modern houses, but comparable to Andrea Palladio's Villa Rotunda in Vicenza, Italy, from the 16th century and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia. In this way, Saarinen demonstrates his own keen understanding of history by linking the Miller House to a specific lineage of great residential designs. But whereas Jefferson and Palladio's buildings dominate the environment through their elevated placement and monumental domes, the Miller House uses a different strategy. Here Saarinen collaborated with landscape designer Dan Kiley to integrate the Miller House into its surroundings using rows of hedges and trees to provide extra privacy.

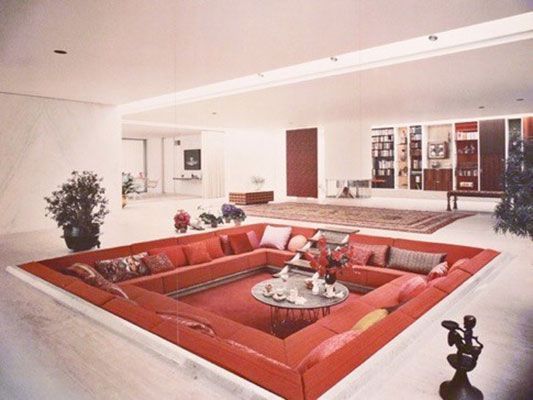

Yet there is tension in this geometric clarity between the private nature of the peripheral spaces of the house and its central gathering space, which also provides a counterpoint to the austerity of the modern design. With its large scale (some 50 feet on a side), the living room provides ample room for the Millers to socialize, but it also contains the famed conversation pit, an invention of Saarinen's interior designer Alexander Girard. The pit's enclosed shape promotes a sense of community and in some cases intimacy, heightened by the bright colors that both enliven the space and underscore its centrality in Saarinen's overall conception.

Ingalls Ice Rink, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Saarinen completed several buildings for Yale, his alma mater, among which the Ingalls Ice Rink was the first. Oddly, despite the fact that Saarinen was Finnish, he had never designed any sporting venue before, let alone a hockey rink. Thus, when Saarinen received the commission in 1953, he sent some of his office staff to go around the United States to look at similar structures to find out what a well-designed hockey rink looked like. Upon their return, his staff delivered a unanimous report: they all looked horrible!

The solution that Saarinen produced consists of an oblong structure surmounted by a massive, wide, very strong concrete arch - in fact, the upper portion of a catenary - which stretches the entire length of the building's spine. From this are hung cables on each side that provide the contour of the wood-paneled ceiling, and roof above. The distinctive exterior humpback shape has given the building the affectionate nickname "The Yale Whale," which is underscored by an elongated protruding spike above the entrances at each end of the building, which is surmounted by a set of four lights. It evokes the image of the end of a harpoon that pierces the body of the whale, appropriate for New Haven, a former port for the whaling industry in the 19th century. On the inside, however, this use of maritime themes is turned upside down, as many have compared the arched wooden ceiling to the overturned interior of the hull of a great Viking ship, thus also connecting the building to the cold climates and northerly regions associated with winter sports like hockey.

The Ingalls Rink therefore represents an ingenious marriage between modern engineering and organic form, a kind of forward-looking solution that nonetheless pays homage to historical, regional themes. It also noticeably closes its interior off almost completely from its surrounding environment. These aspects constitute a quite unusual and distinctive achievement for the 1950s, disclosing Saarinen's ambition to avoid slavishly associating himself with a particular style or simply popular trends, but to carve out his own niche within the profession.

Tulip chairs and tables

Saarinen had trained at Cranbrook in the 1920s and taught there in the '30s, during a period when the school was becoming an epicenter of design talent and instruction. As a result, he had the chance to train, teach, and design alongside some of the brightest minds in the field. In the 1930s he even taught Florence Schust, who would later become the head of the furniture manufacturer Knoll, which had been founded by her husband. It was through his relationship with Florence Knoll that Saarinen was able to develop the designs for the Tulip series of furniture.

Saarinen's concept for the chairs, which have variants both with and without arms, grew out of his design for the table, which has a seamless kind of unity wherein the stem flares into a single wide circular base and likewise expands into the thin flat expansive tabletop, as if to use a minimum of effort to achieve the full function of the piece. The chairs are supposed to mirror this kind of unity, with Saarinen observing that "[t]he undercarriage of chairs and tables in a typical interior makes an ugly, confusing, unrestful world. I wanted to clear up the slum of legs. I wanted to make the chair all one thing again." Indeed, the chairs and tables appear to be sprouting out of the floor, as if they not only display their own sense of unity, but a complete harmony with the larger interior space they occupy. Not surprisingly, the design has also commonly been called the "pedestal chair" for its similarity with display stands.

The ease of the aesthetic of the pedestal chair belies the difficulty in the engineering of the design. Saarinen had originally hoped each unit could be made completely out of a fiberglass structure, but the pedestal proved too fragile to support the weight of a human body. Instead, the pedestal is made out of cast aluminum - which keeps the structure light - covered with a plastic veneer, while the upper portion of the actual seat remains fiberglass. The separation of the two parts also fortuitously allows for the user to swivel 360 degrees, arguably increasing the utility of the chair from that of Saarinen's original design.

Cast aluminum and fiberglass - Manufactured by Knoll, New York City

Trans World Airlines Terminal Idlewild (now John F. Kennedy) International Airport, Queens, New York

The TWA Terminal (or Flight Center) is, along with the main terminal at Dulles International Airport in Virginia, one of Saarinen's two masterpieces of design for aviation; even sixty years later they remain - virtually unaltered - as some of the most iconic examples of the type. The terminals arguably represent the ultimate in space-age design and the sculptural possibilities of poured reinforced concrete. In the TWA Terminal, now actually disused and slated for potential conversion into a airport hotel lobby, Saarinen evokes the idea of flight in several ways, most strikingly with the roof of curved shells that extend from either side of the central pavilion. From an angle the building appears like the body of a giant eagle about to take off, with its head extending over the driveway.

Inside, the sense of glamour and drama of the experience of air travel are made fully apparent with a huge open foyer whose elevation continues to rise as the passenger makes their way from the entrance towards the jets gathered at the rear, as if to physically express the idea of taking off from the airport. This is accented by the massive inclined curtain walls of windows that flood the space with sunlight during the day, as well as by the catwalk that spans the interior foyer, allowing the smartly-dressed passengers to be seen in all their finery before boarding. The effect of moving through the spaces - including its lounges, restaurants, and boutiques - is thus that of a modern promenade, an updated version of the experience of ascending the staircase in the first-class cabin of a great ocean liner.

Saarinen's terminal was constructed at the dawn of the jet age that promised sleeker aircraft with luxurious appointments for its patrons. Ironically, however, the terminal itself became obsolete before it was finished, as it could not accommodate the larger wingspans of Boeing 707 aircraft to connect directly to the terminal through jetbridges; passengers were thus forced to walk out onto the tarmac to board their planes. Nonetheless, the building continued to serve as TWA's major international Atlantic coast gateway until its acquisition by American Airlines in 2001. JFK's new Terminal 5 was eventually constructed around its rear, ensuring that the TWA Flight Center could never be used again for its original purpose, though it is possible to visit it on occasion during open house events.

Hill College House, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Saarinen's only work in the state of Pennsylvania, Hill College House is exemplary amongst his numerous designs for student housing on American university campuses. It was originally constructed as a women's dormitory, and several aspects of it speak to Saarinen's extraordinary sensitivity to the program for the commission. The building employs a skin of rough red brick that firmly ensconces it within the building traditions of both Penn's campus and Philadelphia more generally. It is encircled by a steel fence, crowned by another fence at the roofline, and is entered by a bridge over a ravine, all features that point to the picturesque medieval architecture normally associated with college campuses but also with castle-like fortifications, thereby adding an extra layer of security - theoretically an important feature for women's housing. Such a connotation is emphasized by the slit-like windows that alternate between vertical and horizontal orientations in order to break up a potentially monotonous facade.

The severe brick envelope, however, only underscores the way in which Hill College House brings its residents together on the inside; indeed, Saarinen's guiding theme when designing the complex was "a small village, self-sufficient, inward-focused and protected." The building consists of four separate multilevel wings of dormitory suites that each originally accommodated 16 to 24 students. These wings converge in a great five-story atrium flooded with light, with a cafeteria on the lowest level and projecting communal lounges overlooking it from the four wings, an effect that one original resident compared to living "in a Mediterranean town." Its centerpiece is a large 1926 N.C. Wyeth painting, moved to the atrium in 1978 from New York, entitled The Apotheosis of Franklin, an homage to one of Penn's founders, Benjamin Franklin.

Saarinen designed all the interior surfaces to be white, because, as he quipped when presenting the building to the press, "the walls in my house are white and I wouldn't want anything else" - though he also claimed, in perhaps his one concession to individuality in the structure, that white made them as neutral as possible in order that students might easily personalize their spaces.

CBS Building, New York, New York

The CBS Building in midtown Manhattan was the last major project that Saarinen took on before his death in 1961; it was finished by his senior designers, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, whose firm succeeded Saarinen's practice. The 38-story CBS Building serves as the headquarters of CBS Corporation, but not the actual broadcast centers for any of its media. It is Saarinen's only true skyscraper, and it is rightly considered his answer to the International Style image of American corporate modernism that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and other firms were establishing as a paradigm in the 1950s.

The constructive aspects of the skyscraper set it off from the traditional exposed steel-frame glass prisms pioneered by Mies. It consists of a reinforced concrete frame - the first such skyscraper in postwar New York - with triangular-plan spandrels that act as load-bearing piers set in between the exterior windows. The concrete exterior piers are clad in black Canadian granite and complement the dark-tinted windows set back between them. When one stands at an angle to the building, the triangular shape of the spandrels hide the windows as if turning a set of Venetian blinds. Meanwhile, the projection of the triangular spandrels from the plane of the windows extends for the full height of the building and produces a soaring effect by accenting the verticality of the form. The building thus appears almost like a polished stone monolith set apart from its neighbors in a larger plaza, which quickly earned it the sobriquet "Black Rock" upon its completion in 1964.

Saarinen's tower still aligns with the facades of its neighbors along the Avenue of the Americas in midtown Manhattan, but his use of the plaza was responsible for a change of New York zoning regulations for design of skyscrapers. Since 1916 these laws had encouraged progressive step-back designs to prevent towers from blocking light that otherwise filtered down into the streets; after 1961, the open-plaza model as seen with the CBS Building was encouraged instead.

The CBS Building should also be noted for its significant process of collaboration between the architects and their client, CBS chairman William S. Paley. Paley took an active role in various aspects of the design, specifically selecting Saarinen because he wanted a building that would break from the Miesian mold of the International Style, and courageously stuck with Saarinen even though he did not like the initial design. Paley took an active role in various stages, meeting with Roche and Dinkeloo at least thirty times to view some full models of the structure, adjusting the precise width of the window panels and the selection of the granite for the exterior - a color that Saarinen thought would echo the gray suits of executives. The building received much critical acclaim upon its completion, underscored by the fact that it helped establish the famed Broadcast Row of radio and television media on Sixth Avenue, that includes the headquarters of NBC at Rockefeller Center as well as Fox further south, and previously included ABC and CNN.

Gateway Arch, St. Louis, Missouri, USA

Officially only a portion of the larger Jefferson National Expansion Memorial that commemorates a number of different events - including St. Louis' status as the oft-cited gateway to the West - the Gateway Arch is nonetheless justifiably often considered as a monument unto itself, due to the colossal singularity of its form. Saarinen and his design team actually titled their competition entry "Gateway to the West," and the name stuck.

The story of Saarinen winning the 1948 competition for this monument, instead of his father is well-known, but less so is the controversy Eero's winning design generated when it was first published. Saarinen was accused of having stolen the idea of the arch from the unrealized plans of Benito Mussolini for a grandiose world's fair to be held in Rome in 1942 celebrating twenty years of Italian Fascism. The competition jury quickly settled the matter with a statement that decreed the concept of an arch was not a Fascist invention, but this did not stop Time magazine from referring to the St. Louis arch as "Mussolini's wicket."

Saarinen based the arch on the reverse form of a catenary (the curve a chain forms when hung between two supports), which is the strongest form of an arch because of the way that it channels all of the weight of its structure into the ground as opposed to leaving lateral forces that need to be buttressed. Saarinen, however, used artistic license by making the arch slightly taller than a pure catenary and slimmer at the top rather the bottom, which produces a more soaring, dramatic effect. The arch's cross-sections consist of double-walled equilateral triangles of stainless steel connected to each other by a layer of concrete. This creates a self-supporting stressed-skin structure, very similar to the designs of the bodies of airplanes, another new technology that was coming into much more widespread use with the advent of the jet age at the end of the 1950s.

Delays prevented the arch from being constructed until 1963-65, and Saarinen's death in 1961 diminished in part the recognition he received for its design, conceived over fifteen years earlier. Despite his bold vision, the feasibility of successfully completing the arch was in doubt throughout the planning and construction process, even with the calculations of Saarinen's trusted engineers Fred Severud and Hannskarl Bandel. Anticipation heightened as the arch's twin legs rose from the ground, with local radio stations broadcasting when further sections would be installed on site by the custom-built creeper cranes. Justly hailed as a triumph of modern engineering on its completion, it remains both the tallest man-made monument in the United States and the tallest arch in the world.

Biography of Eero Saarinen

Childhood

Eero Saarinen was, along with Louis Kahn, one of the two great European emigres who would become titans of midcentury American architecture. Both were born in areas around the Baltic Sea that, at the time of their births, were technically part of Russia, though Saarinen's family was decidedly Finnish (Finland became independent of Russia during the 1917 Russian Revolution), and both immigrated to the United States as children.

Unlike Kahn, who was born into very modest circumstances, Eero Saarinen (whose first name translates to "Eric" in English) came from a very artistically-inclined and cultured family. His father Eliel Saarinen - with whom he shared his birthday, August 20 - was a highly accomplished Finnish architect, one of the masters of Art Nouveau in Finland, who had designed the central railway station in Helsinki and, along with two other architects, built a combination architects' house and studio complex called Hvittrask, in the woods east of Helsinki, in 1903.

Eliel's second wife Loja, Eero's mother and sister of Eliel's former partner, was herself an accomplished sculptor. The Saarinens were friends with many cultural luminaries of the period. Eliel was very close to the composer Jan Sibelius, and on at least one occasion the family welcomed the Marxist writer Maxim Gorky into their home to help him evade Russian authorities.

Eero grew up literally in his father's architectural office. Often as a very young child he would be sitting under his father's drafting table drawing while his father would be working on commissions right above his head. Reputedly, every day he would ask one of his father's draftsmen, named Otto, to draw him a horse. Later, when Eero interviewed potential employees in his own office, he would have them draw him a horse, claiming that he could tell how good a draftsmen anyone was from about two or three strokes of sketching the figure.

Education

The Saarinens immigrated to the United States in 1923, after Eliel's entry in the famed Chicago Tribune Tower competition won second place. (The same week, Eero won a matchstick design contest sponsored by a Swedish newspaper, which netted him 30 Swedish kroner, the equivalent of about $8 at the time.) Two years later, Eliel accepted an invitation to design the campus for the Cranbrook Academy of Art, just outside of Detroit, Michigan; in 1932 he would later become head of the institution. Eero, predictably, matriculated to Cranbrook, where he made friends with Charles Eames, Ray Kaiser, and Florence Schust. (Kaiser would later marry Eames to form the famous design duo, and Schust would later marry Hans Knoll and become head of the Knoll furniture company, for which Saarinen would produce some of his most famous pieces.) In 1929, Eero entered the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris to study sculpture, his only real foray into anything besides architecture and interior design.

Between 1932-34, Eero studied at the Yale School of Architecture, where he won a small travel fellowship that allowed him to journey after finishing his studies to Europe and North Africa, where he became intimately acquainted with the architectural history of these various regions. He ended up in his native Finland, where he briefly got a job for a year in 1935 working in a local architecture firm.

Early Work

In 1936 Eero returned to the United States and began to teach at Cranbrook and work in his father's architecture firm in Bloomfield Hills, where he would remain until 1950. In 1939 he married the sculptor Lilian Swann, with whom he eventually had two children, Eric and Susan. Eric later went on to become a filmmaker, producing the 2016 documentary for PBS about his father, Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Saw The Future. Lilian was, to be certain, a key influence on Eero, inspiring him to maintain a sculptural, plastic quality in his designs and sometimes contributing relief sculpture to Eliel and Eero's architectural projects. Their marriage, however, was not a particularly happy one. Eero's energies were completely focused on his work, and it was normal for him to spend virtually no time with his family, staying at the office until very late at night and leaving Lilian to look after the children and tend to domestic duties. Eric later recalled, "I always resented my father for literally abandoning my mother, my sister, and me. But I never saw it from his point of view." Eero and Lilian divorced in 1953.

1940 was a banner year for Saarinen. He officially became an American citizen, but even more importantly, he partnered with his friend Charles Eames in entering a competition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York for an upcoming exhibition, Organic Design in Home Furnishings. Saarinen and Eames' entries won in the categories for both chair design (for the famed "Organic Chair") and the living room, for which they were awarded contracts for manufacture and distribution with major department stores (the first day of sales coincided with the exhibition's opening in 1941). This gave Saarinen his first national exposure as a designer independent of his father. In the late 1940s, Eames and Saarinen would both briefly work with John Entenza, editor of Arts and Architecture magazine, on the design for Entenza's own house as part of the Case Study House Program sponsored by the periodical.

Saarinen's career in his father's firm was interrupted in 1942 during World War II, when he was recruited by his friend Donal McLaughlin, from his days at Yale, to join the newly-formed Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which would later morph into the Central Intelligence Agency. There Saarinen became "irreplaceable," according to his superiors, designing situation rooms and military schools as well as prototype models for weapons and other devices. He also drew illustrations for bomb disassembly manuals and developed presentation charts for showing work flows through different parts of the OSS's organization.

Mature Period

Eliel Saarinen died in 1950. But even before then Eero had shown signs that he would make a serious name for himself apart from his father. In 1948, both Saarinens had independently submitted competition designs for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis - literally creating their separate submissions on opposite sides of a wall in the same office. The competition jury sent the announcement that Eero had been named one of the competition's five finalists to "E. Saarinen;" the Saarinen family interpreted this to mean Eliel, and broke out a bottle of champagne in celebration. Two hours later, they received a phone call from an embarrassed official who clarified that Eero Saarinen had advanced in the competition. The Saarinens immediately broke out a second bottle of champagne. Though the mood was celebratory, Eric Saarinen claims that privately it was difficult for Eliel to come to terms with the fact that his son had surpassed him. Eero, of course, would go on to win the competition and the $50,000 prize as the chief designer. His design, the now-famous Gateway Arch, would only be realized posthumously, however.

Eero launched his own architectural practice after his father's death, and in the ensuing decade produced a flood of important buildings and interior projects, establishing him on his own firmly within the canon of great modern architects. Nearly all of his important designs date from this relatively short 13-year period between 1948 and 1961. Saarinen loved models, especially large ones into which he could stick his own head in order to visualize the interior space, and numerous photographs exist showing him and his employees inspecting or constructing them.

Well before his divorce from Lilian, Saarinen had met Aline Bernstein Louchheim, an art critic at the New York Times, and they grew very close. In one of Eero's love letters to Aline, he quite bizarrely compared himself to root vegetables, declaring "You don't realize that I'm like a turnip or a potato, one of those plants that has stored up below ground a tremendous amount of lust for a full blooming life." Aline's promotion of Eero's career had begun even before the two of them married in 1954, and while they were certainly in love, practically their union formed a very potent team for the rest of Eero's life. Aline was instrumental in increasing Eero's profile among American designers, helping him to be featured on the cover of Time magazine in July 1956, an honor previously accorded to such names as Richard Neutra and Frank Lloyd Wright. She also, unlike Lilian, was capable of discussing Eero's work with him on a regular basis. After Saarinen's death, Aline became her late husband's greatest ambassador, frequently appearing on camera and giving interviews explaining the significance of his architecture. The year following Saarinen's passing, she published Eero Saarinen on His Work: A Selection of Buildings Dating from 1947 to 1964 with Statements by the Architect.

Saarinen supposedly also became more of a family man during his marriage to Aline, though his ambition did not shrink and he did not slow down the pace of his work. There were few days during the year when the firm's offices were closed. He expected his employees to follow his routine of working from morning until dinner time, return home for the evening meal and then reconvene to work late into the night. As he once simply quipped, "I would like a place in architectural history."

Death

In August 1961, Saarinen complained of headaches as he was preparing for his firm to move from Detroit to New Haven, Connecticut, and checked himself into a Michigan hospital to seek a quick remedy. Doctors discovered instead that he had a brain tumor, and Saarinen elected to undergo an operation that promised a very slim chance of survival. He died during surgery, having turned 51 just a week and half earlier.

Saarinen's death was shocking, as it was sudden and completely unexpected. His leadership at the firm passed to Kevin Roche, and under him, Cesar Pelli, and others, as Saarinen's numerous projects were brought to completion. Aline was instrumental in convincing CBS to stay with the firm to finish its new headquarters in midtown Manhattan, the commission for which Saarinen had received only the year before.

The Legacy of Eero Saarinen

Initially, Saarinen's fame suffered greatly due to his early death. He was not physically present at the completion and dedication of many of his most important buildings, and could not reap the benefits of sharing the spotlight or attracting new clients as a result. The brevity of his independent career meant that for some he would always be seen as a "flashing glory" whose brilliance was extinguished almost as soon as it began. Though Saarinen's buildings reveal his great sculptural imagination, their engineering challenges also suggest that the conception and realization of them required collaboration with many other brilliant minds, thus reducing the credit that he received.

Saarinen never developed a particular "style" for his architecture, insisting that every problem was different and thus required a unique solution. While during his lifetime he received much criticism for his versatility, notably from the great architectural historian Vincent Scully, this philosophy has come to be adopted by many contemporary architects. To some extent this has also affected his fame, as he did not launch or pioneer a singular style or movement, and there are no easy markers that indicate what makes a "signature" Saarinen building.

During his lifetime Saarinen received a number of honors, including being named a fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1952, from whom he posthumously received the AIA Gold Medal in 1962. In 1954 he was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Saarinen's Gateway Arch is featured on the reverse of the Missouri state quarter, minted by the USA in 2003, and a commemorative 10-euro coin issued by Finland in 2010, which also features a silhouette of Saarinen's Tulip armchair.

Saarinen's reputation has nonetheless steadily grown over the past sixty years. His office attracted a number of talented employees, including Pritzker Prize winners Kevin Roche (whose firm Roche and Dinkeloo became the official successor to Saarinen's practice), Cesar Pelli, and Robert Venturi. The personal papers of Aline and Eero Saarinen were donated to the Archives of American Art by Aline's brother, while Roche and Dinkeloo donated their Saarinen archives to Yale University. Some diazotype copies of Saarinen drawings for the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport also reside at Columbia University in New York. The availability of these sources have prompted the flurry of interest in Saarinen's work in recent years, which includes the major exhibition Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future which toured several locations between 2006-10.

Influences and Connections

![Charles Eames]() Charles Eames

Charles Eames- Lilian Swann

- Eliel Saarinen

- Norman Bel Geddes

-

![The International Style]() The International Style

The International Style ![Modern Architecture]() Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture

- Alexander Girard

- Dan Kiley

- Kevin Roche

- Robert Venturi

- Cesar Pelli

- Harry Bertoia

Useful Resources on Eero Saarinen

- Eero Saarinen (2014)Our PickBy Jayne Merkel / A monograph of major works by the architect

- Eero Saarinen: An Architect of Multiplicity (2003)By Antonio Roman / Monograph including illustrations and models of famed works and furniture designs

- Eero Saarinen: Objects and Furniture Design, By Architects Series (2013)Our PickShowcase of furniture and object designs by the architect