Summary of William Hogarth

Best remembered for his intricate and satirical prints, Hogarth was a varied and prolific artist who mastered a range of styles and genres ranging from conversation pieces and realistic portraiture to grotesque caricature. He was the most significant artist of his generation and the first English-born artist to attract attention abroad. Hogarth invented the idea of a narrative series of prints, which told a story through a number of images, and he produced a significant number on "modern moral subjects" from prostitution to politics. In doing so he provided a visceral social commentary, highlighting and lampooning corruption and presenting images of the seedy underbelly of London, which had rarely been portrayed before. It was these unique prints that brought him wealth and fame in his own lifetime and beyond, as well as influencing the work of 18th century novelists in their subject matter and focus on individual narratives. The prints can also be seen as the forerunner of cartoons and comic strips.

Accomplishments

- Hogarth drew readily on the scenes of everyday life that he had witnessed growing up in relative poverty as a child. His engravings often depict those trying to survive on the fringes of society and his prints are characterized by an incredible eye for detail (including many subtle puns and references), an often bawdy and ribald humor, and an ability to render striking and individual faces.

- After witnessing the widescale plagiarism of his first series of prints, A Harlot's Progress (1732) by competing engravers who produced cheap and inferior copies, Hogarth lobbied for the introduction of copyright protection for engravers. This was enacted in 1735, and became known as Hogarth's Law - it was one of the first of its kind in the world.

- Hogarth is viewed as the founding member of The English School, the dominant school of painting in the UK throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries and the first distinctly native style that the country produced. His paintings drew on the French Rococo aesthetic but Hogarth added a layer of realism to his work which was innovative. This coupled with his ambition, popularity, and storytelling ability went on to influence the works of Reynolds and Gainsborough amongst others.

Important Art by William Hogarth

A Harlot's Progress - Plate III

This plate was the third in a series of six engravings (based on paintings of the same name) that charts young Moll Hackabout's life in London. The fictional character came to the capital from the country in the hope of finding work in service. Instead she is taken advantage of and becomes a high-class prostitute, before falling on the hard times depicted in plate III. By plate IV she is dying, toothless and pockmarked by venereal disease, while the final plate shows her funeral wake with her young illegitimate son sitting by her coffin.

In this composition, Hogarth mimics the very common religious depiction of the Annunciation, to satirically highlight the fall of the young woman. Moll is in shabby room in Drury Lane, getting out of bed after a leisurely lie-in. The witch's hat and switch on the wall communicate to the viewer that her current position necessitate her to indulge in flagellation and black magic. Above her bed is a box belonging to the famous highwayman James Dalton, suggesting that he is now her principal lover. She is less well dressed than in the previous plate and she dangles a watch from her fingers, no doubt obtained illegally from the previous night's customer. The piece is full of pictorial puns and detailed references including the domestic cat at Moll's feet which hints at her profession.

Moll's ultimate downfall is foreshadowed by the serving woman at her side, who has lost part of her nose to syphilis, and has a sore on her face. While Moll looks smiling and suggestively at the viewer, behind her a magistrate and officers enter to arrest her. As writer Susan Elizabeth Benenson writes: "Like his great predecessor, the 16th-century Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hogarth wanted to extract entertaining and instructive incidents from life. In telling the story of a young country girl's corruption in London and her consequent miseries, he not only ridiculed the viciousness and follies of society but painted an obvious moral."

This work was instrumental in securing Hogarth's reputation as the great moral and satirical artist of his time. The use of multiple scenes in his work allowed him a more complex narrative, and led to his reception as a "literary artist". 18th century essayist and poet Charles Lamb wrote: "His graphic representations are indeed books: they have the teeming, fruitful, suggestive meaning of words. Other pictures we look at - his prints, we read." The original paintings were destroyed in a fire in 1755. In 2006 the works were taken as inspiration for the film A Harlot's Progress, directed by Justin Hardy.

Etching and engraving - Andrew Edmunds, London

A Rake's Progress

The Tavern Scene, plate III of the Rake's Progress Series, shows a debauched and lively evening of drinking at the heart of which is Tom Rakewell, the anti-hero of the work. Another fictional character, Tom, like Moll, came to the city to build a life, only to succumb to its temptations. The previous two plates show Tom returning from University to learn his wealthy father has died, leaving him everything. He immediately shuns his pregnant girlfriend, and by plate III we find him drunk in the early hours at a brothel. At his side is a prostitute with a face pock-marked by venereal disease, reaching under his shirt, probably to rob him. Surrounding him are other fallen characters; a stripper undresses in the foreground, a tradesman to the rear fondles a prostitute, and two women prepare for a spitting contest.

Before he produced engravings of the series of paintings, Hogarth exhibited the oils in his home, as a preview. They acted as an advert for the prints which he later sold on subscription. In the work we see Hogarth's expertise in creating a claustrophobic intimacy that forces us to look at the subjects, and therefore our own experience, as they gamble, cheat, and ultimately fail. The rake in this case ends up being arrested and ends his days in Bedlam, a London asylum.

As Christine Riding explains: "Hogarth in a masterly way presented each scene with a realism and intimacy that established his artistic identity as the roving satirist who observes with an unflinching eye the seedier side of London life." Ultimately, it was his skill in doing this, his eye for detail, and his ability to create comedy and caricature, that made him famous.

Oil on canvas - Sir John Soane's Museum, London

Marriage à la Mode: I The Marriage Settlement

Another of Hogarth's series, Marriage à la Mode tells the story of a disastrous union of convenience, between a profligate aristocrat's son and the daughter of an aspiring middle-class merchant - the sole purpose of which is the exchange of wealth for social status. This first scene The Marriage Settlement sets the stage, making it clear that this is a business arrangement, rather than a union of love. This is echoed in the dark and somber room in which the couple themselves have been pushed to the side of the canvas. The bride, dressed in white is almost doubled over in sadness as she grips at her handkerchief, indicating tears shed. She faces away from her foppish betrothed who, caught in his own reverie as he stares at his reflection, is completely oblivious to the business dealings going on around them.

The groom's father can be seen on the right of the canvas, gesturing to himself proudly while he rests his gout-ridden and bandaged foot on a stool. With his other hand he points to a family tree, indicating an unlikely lineage that goes back to the Normans. The message is clear; he is selling his son for cash. Meanwhile, the rich merchant on the other end of the transaction is flanked by his lawyer. The house framed in the window encapsulates the symbolism of the work; it is all for show, like the marriage.

The work has its origins in Dutch and French group portraiture, but in Hogarth's conversation piece, he uses satire to take it to another level. Historian Professor Amanda Vickery described the work as a "vicious depiction of aristocratic culture and marriage as barter and sale. The fact that this will be utterly loveless marriage is signified by two chained dogs - it will be a prison." This series was one of Hogarth's most popular and both the original paintings and the later engravings exemplify his skill in composition and in rendering individual characters. The work inspired James McNeil Whistler when he saw it exhibited at the National Gallery.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery

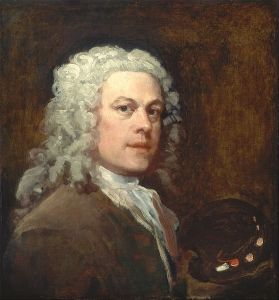

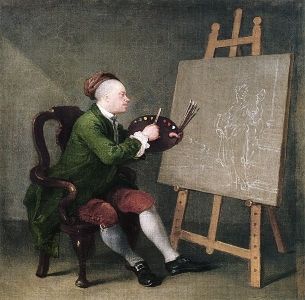

The Painter and his Pug

Although finished in 1745, Hogarth actually began this painting around a decade before and X-rays show that he made various alterations over the period. He had originally painted himself in a wig and formally attired, but at some point he decided rather than a gentleman painter, he wanted to present himself as an artisan and introduced the hat and banyan (an informal robe). At the front of the work is Trump, Hogarth's pet pug. This is a very personal touch and possibly a reference to his pugnacious personality. Hogarth's image is displayed on an oval canvas which rests on three books by well-known English authors; Shakespeare, representing drama, Milton, representing epic poetry and Swift, for satire, the three tropes on which Hogarth built his oeuvre. In the foreground is a palette, emphasizing Hogarth's career in painting. The palette bears an s-shaped curve and the words "the line of beauty". In introducing these elements, Hogarth pre-empts his later treatise on The Analysis of Beauty and shows that he was already formulating the ideas that he presented in it.

Biographer Jenny Uglow wrote that the work should "be labelled a still life not a self-portrait - nature morte - not vivant. It is a painting of a painting, an oval stretched on the canvas with the nails still showing. In these receding dimensions, the pug who sits in front of the painting is more 'real; than his 'painted' master." This reflects Hogarth's lively sense of humor, as his beloved pet dog becomes a focal point of his own self portrait. In this same humorous vein, Trump appears in a number of Hogarth's other paintings, including as a puppy in The Fountaine Family (1730) and in Captain Lord George Graham in his Cabin (1746) in which he is portrayed wearing Graham's wig. The painting demonstrates both Hogarth's professional ambition as a painter and his skill in portraiture, evident in the use of color and tone and his assured brushstrokes.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

![The Analysis of Beauty - Plate II [The Country Dance] (1753)](/images20/works/hogarth_william_5.jpg?1)

The Analysis of Beauty - Plate II [The Country Dance]

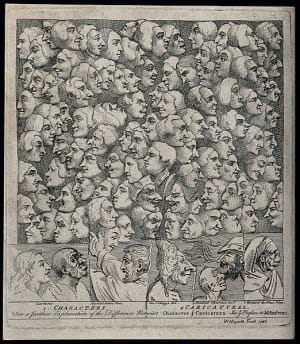

This engraving, taken from Hogarth's book on beauty, acts as a demonstration of his key tenets. He employs the serpentine line throughout in an assertion of his belief that it was both beautiful and graceful. The artist wanted to propose a counter-argument to conventional teaching in art, an "alternative to the classicising aesthetic of the connoisseurs". The heart of his argument, according to art historian Christine Riding, was that the serpentine line was the essence of beauty, "as opposed to the straight lines that were emblematic of classism and the vulgar, exaggerated curve, both of which lacked 'variety'."

The scene shows a country dance and is characteristically busy with human activity. Curving lines can be seen in the dynamism of the dancers, the ruffles of their clothes in movement, the candelabra, and even the overall shape of the dance line. Framing the work on all sides are sketches that illustrate Hogarth's teachings. Elsewhere in the text Hogarth focuses on the real female form as a source of beauty, rather than inert marble busts from antiquity. A reference to this can be spotted in figure 74 in which a woman dressed in a toga comes alive, as if stepping off her plinth and into the dance. Whilst Hogarth's theories were predominantly well received, there were some dissenting voices who satirized and ridiculed the publication. Nevertheless, Riding notes that The Analysis of Beauty was a "complex, innovative and thoroughly modern theory on art, beauty and life. The concept reverberates even today, and is explored in Alan Hollinghurst's Booker-winning novel of 2005 The Line of Beauty.

Etching and engraving - Andrew Edmunds, London

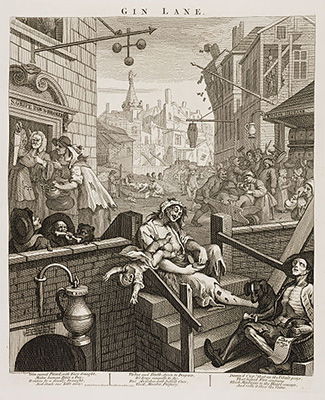

Gin Lane

Hogarth produced this engraving as a counter to the gin-craze that he could see gripping London. In the foreground of this urban dystopia, are instances of infanticide (committed by a half-naked women covered in syphilitic sores) and starvation caused by the spirit, while behind a rabble causes chaos, destitute tradesmen sell their tools to buy more gin and a woman pours alcohol into an infant's mouth. There are also instances of suicide, madness, and murder. These activities are seen as foreshadowing wider societal breakdown, symbolized by the collapsing building in the distance.

The work was produced in tandem with the writing of Henry Fielding, a judge and one of Hogarth's friends. Fielding published influential writings examining the rise of crime and social unrest that accompanied mass urban migration into the capital during the first half of the 18th century. These problems were caused, in part, by a 1689 Act of Parliament that banned the import of French wine and spirits. As a result, gin, originally a foreign spirit, began to be produced in England. It was cheap and addictive and was seen to have an impact on health, productivity and crime. Gin Lane formed part of the campaign in support of the 1751 Gin Act, which aimed to reduce drinking in a bid to curb social disorder.

As art historian, Mark Hallett notes this work acted as a "horrific social satire in which anonymous, poverty-stricken alcoholics, their features depicted in the boldest of engraved lines, sprawl, fight and die among the ruins of a collapsing city". The prints were aimed to shock the working classes into reformation and would have sold for a cheaper price than Hogarth's previous prints. This ensured a larger circulation, but the cost would still have been prohibitive for many. The print was, however, displayed in shop windows, workshops, coffee houses, and taverns increasing its impact.

The piece forms one of a pair with Beer Street and the two were created to be viewed in unison. Unlike Gin Lane, Beer Street celebrates the traditionally British brewed drink, linking it to prosperity, health, and happiness and positing it as an alternative to gin. There are numerous links between the two pictures, for instance the pawnbrokers seen as so active in Gin Lane is dilapidated and run down in Beer Street as no one has need of it. These two pieces, along with works such as The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751), mark Hogarth's move away from satirizing fashionable high society to presenting a biting commentary on crime and poverty.

Etching and engraving - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of William Hogarth

Childhood and Education

William Hogarth was born on November 10th, 1697 in London. His father, Richard, was a classical scholar, but although well-educated, was not wealthy, making a precarious living as a schoolmaster, from writing Latin and Greek textbooks and, later, as a coffee house proprietor. The Hogarth family moved a number of times during Hogarth's early years, but always remained within the bustling East End of the city, near to Smithfield Market.

In 1705, William's older brother (also named Richard) died at the age of ten. Infant mortality rates were high and an older brother and two sisters had already died before Hogarth was born; only William and his sisters Mary and Ann survived to adulthood. Hogarth biographer, Jenny Uglow writes: "In those days, children were not kept away when sickness struck. Rooms were darkened, parents wept, and local women came in to lay out small bodies. Bereft of his older brother, [William] had to adjust to the new role as the eldest child."

Around 1708, the Hogarth coffee house failed and Hogarth's father fell into debt, resulting in him being detained in Fleet prison. The family moved to cramped rooms nearby in Black and White Court and Richard was allowed to join them at this address in 1709, the property being within the bounds of the wider prison jurisdiction. It is probable that his mother Anne and Wiliam himself, as the eldest son, worked to maintain the family during the four years that his father was imprisoned. Both London's East End and the area around Fleet Prison was impoverished and crime-ridden at the time, and it is probable that Hogarth's birthplace and childhood homes had a significant impact on his later career and choice of subjects.

During his father's incarceration, Hogarth is unlikely to have attended school as this cost money, but it is probable, given his competence in Latin and French, that his father tutored him in these subjects. At the age of 16, Hogarth was apprenticed to a silver engraver, engraving items such as watch cases, plates and cutlery, usually with heraldic designs. Although he quickly became bored by his work, Hogarth was a sociable and convivial character, and during his days as an apprentice enjoyed the hubbub of London life. He would visit coffee houses and theaters, befriending writers, musicians and actors and his love of the theater can be seen the theatricality of many of his later works. He also liked to walk, and would explore the city streets, sketching the characters that he saw around him.

Mature Period

In 1720, Hogarth left his apprenticeship early and, at the age of 23, successfully set up his own shop offering silver engraving as well as copper etched plates for printing business cards and book illustrations. It is not clear where he learnt this skill, but he was clearly adept at it by this date when he produced his own shop card by way of advertisement.

Eager to develop his drawing and painting, he started attending classes in St Martin's Lane and in 1724 he joined a drawing school at the home of history painter Sir James Thornhill, an artist he had long admired. At the age of 30, Hogarth began his painting career in earnest, and found success producing "conversation pieces" for wealthy patrons. These paintings showed groups of men and women at leisure and were rooted in the Rococo work of Antoine Watteau. He sometimes found these paintings tedious, however, and as a way of alleviating the boredom he also began to produce sketches and engravings of humorous everyday scenes, pieces that would pave the way for his later works of commentary on contemporary life.

In March 1729 Hogarth eloped with Thornhill's daughter Jane. They did not have any children, but had a long and happy marriage living in between London and the Essex countryside. The following year he began his work on his groundbreaking A Harlot's Progress, a series of six paintings (which he copied and circulated widely as prints) that told a story of a young women's corruption and subsequent decline in London. It was a critical and commercial success, bringing him recognition, and financial and artistic independence. The money generated by the work also allowed Hogarth and his wife to move to London's more fashionable West End.

The series became so popular that it was widely copied and produced as cheap, inferior engravings for the mass market by Hogarth's competitors. As Hogarth received no payment for these copies and the poor nature of the artwork damaged his reputation, Hogarth lobbied parliament to provide legal copyright protection for engravers such as himself. This was passed in 1735 as The Engraving Copyright Act, also known as Hogarth's Law, and was one of the first of its kind in the world. Although he had completed The Rake's Progress, his second series of images, he waited to publish until the law was fully passed.

Hogarth continued to socialize with other artists and designers, frequenting the well-known Old Slaughter's Coffee House on St Martin's Lane, a haunt for intellectuals. From here he set up the St Martin's Lane Academy in 1735, a precursor to the Royal Academy, which was not formally established until more than three decades later.

Late Period

Hogarth followed the same pattern for a number of his later works, producing a series of paintings, and then selling the prints of them at a price that targeted the new, moneyed middle classes. He saw real success from his series Marriage A-la-Mode (1745) which was aimed specifically at a middle-class audience in that it poked fun at the aristocracy. The six-part series told the story of the fictional aristocratic family The Squanderfields who had fallen on hard times. Their solution was to marry their son into a wealthy merchant family, but this marriage of convenience ended in disaster, as the final plate demonstrated.

Hogarth also continued to produce paintings and was a skilled portrait painter and colorist, but the success of his prints eclipsed public appetite for his painting. Around 1740 he produced a full-length portrait of philanthropist and founder of the Foundling Hospital, Captain Thomas Coram, which was widely praised and imitated. By 1751, however, Hogarth had become disillusioned by the disappointing amount of money his paintings made at auction. As writer Susan Elizabeth Benenson says: "Hogarth, in anger and mortification, retreated into aggrieved isolation, pursuing his philanthropic interests but adopting, in public, a defiant and defensive pose that involved him in increasingly rancorous debate on artistic matters." He took on a number of charitable roles and began to produce prints that were more focused on poverty and social issues.

In 1753 he wrote The Analysis of Beauty, an aesthetic treatise in which he rejected the formal style and proportions of the Italian Old Masters, expressed the importance of variety in art, and pro-posed that the serpentine line was central to all forms of beauty. The book sold well, but also opened him up to criticism from the establishment and most prominently by the young artist, Paul Sandby who created a number of satirical prints directly targeting Hogarth and his work. The book was heavily influenced by Hogarth's own practices and it had limited impact on the work of other contemporary painters. In his enthusiasm for the serpentine line, however, Hogarth reflected the art and design of the Rococo and preempted its importance in the later Art Nouveau movement.

In 1759 Hogarth produced a work entitled Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo, which he had hoped would establish him as a respected history painter, but the wealthy patron who had commissioned it, Sir Richard Grosvenor, rejected it. It also received a number of poor re-views. Hogarth was furious and humiliated and in response to criticism, he removed it from exhibi-tion.

Hogarth returned to prints in 1762, producing The Times, a series of elaborate political allegories which shocked and divided the public. Offending right-leaning journalists, a counter attack was launched and Hogarth himself, again, became the subject of satire. Journalists and activists, John Wilkes and Charles Churchill accused Hogarth of falling into moral, mental and physical decline. A feud was born that lasted the rest of the artist's life. Hogarth died at home on October 25, 1764 from a ruptured artery and was buried near his second home in the countryside of Chiswick.

The Legacy of William Hogarth

Hogarth had been controversial among his peers. As Stephen Deuchar noted, when he was director of Tate Britain: "Hogarth's contemporaries found him always 'ingenious', variously zealous, flamboyant and self-righteous - a consummate operator and occasionally naive...His art was rarely considered to lie amidst the realms of greatness occupied by the Old Masters, whose uncritical devotees he so readily mocked."

This statement is supported by the writings of Joshua Reynolds, first president of the Royal Academy, who rejected Hogarth's attempts at history painting. In 1788, Reynolds said Hogarth should be celebrated for inventing "a species of dramatic painting" and for his ability "to explain and illustrate the domestic and familiar scenes of common life", but that his ambitions in the "great historical style" were not only impudent but presumptuous.

Hogarth's work, however, did lay the foundations for the English School of Art, a movement which marked the emergence of a national artistic tradition. As art critic Jonathan Jones says: "Before Hogarth, there was not really any such thing as British art. There was art made in Britain, by such great European masters as Rubens and Van Dyck. But it was Hogarth who created the idea of a British school."

Though the artist was praised and remembered after his death - especially in terms of the variety of work he produced, Hogarth's legacy wasn't fully appreciated in his lifetime. As John Constable said: "Hogarth has no school, nor has he ever been imitated with tolerable success." Hogarth later found following in the Romanticism movement especially in literature. His series led the way in the exploration of individual experience, which became a key motif of 18th century novels.

Hogarth's work was also hugely important in promoting British painting and engravings abroad. He had a profound influence on James McNeill Whistler, who in 1901 campaigned for Hogarth's Chiswick home to be preserved for future generations, writing angrily that "I am told that nothing official has been done, either by the Government, or The Royal Academy, to keep in respect the memory of [the nation's] one 'Master' who, outside of England, still is 'Great'." Whistler had been given a book of Hogarth's engravings as a child, and was inspired by the artists' paintings - specifically his brushwork and use of color. His multi-focal compositions can also be seen as inspirations in the work of David Wilkie (who was celebrated as "the Hogarth of his day"), William Powell and Ford Madox Brown.

Today Hogarth is best recognized as a satirist, who, as art historian Mark Hallett notes "offered an acidic and sometimes comic vision of a society mired in corruption and hypocrisy, and who told remarkable pictorial stories about the flawed and ill-fated individuals - prostitutes, rakes, alcoholics, yokels, thieves and murderers - who lived and died outside the boundaries of respectable society".

Influences and Connections

- Sir James Thornhill

- John Vanderbank

-

![James Whistler]() James Whistler

James Whistler -

![Ford Madox Brown]() Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown ![Walter Sickert]() Walter Sickert

Walter Sickert- James Gillray

- William Powell Frith

- George Vertue

-

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism - The English School

Useful Resources on William Hogarth

- The Analysis of BeautyBy William Hogarth

- HogarthOur PickBy Mark Hallett and Christine Riding

- Hogarth (Art and Ideas)By Mark Hallett

- William Hogarth: A Life and a WorldOur PickBy Jenny Uglow

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI