Summary of Rosa Bonheur

From early childhood Rosa Bonheur had a liberal outlook and defiant personality, attributed in part to her father's belief in a form of socialism whereby class and gender distinctions were radically dissolved. As such, even though born at a time when women were not admitted to art school and most typically became absorbed into a life of domestic dependency, this was not Bonheur's fate. With her father's support she began to paint prolifically from her early teenage years, by mid career she had been awarded many prestigious accolades previously only achieved by men, and in later life she was famous and independently wealthy.

Alongside her English counter-part, Edwin Landseer, Rosa Bonheur was the foremost French "animalier" (animal painter) of her age, and arguably of all time. Bonheur's work was linked to landscape painting and the Realist tradition, but also spoke of a connection between nature, art, and society that ran deeper than the observational platform from which the canvases initially sprang. As the influential theorist John Ruskin well articulated in 1847, by painting surrounding nature, "by rejecting nothing; believing nothing", that then, effortlessly and organically "the truth" emerges. In this 'truth' there is a subtle moral lesson of equality to be learnt, that even animals have a soul, and that all (and this applies to humans now too), no matter how big, small, dark or light, deserve attention, care, and visibility. Rosa Bonheur said herself that she was 'wed to her art'. As such, her pictures become her children painted with unfailing dedication and exquisite tenderness. She was a pioneer for an alternate family structure, spending her life in a same sex partnership devoted to the creation and care of animals and art works.

Accomplishments

- Rosa Bonheur is an early example of a feminist. She lived entirely independently, with no need of any financial support beyond her own living made from painting. Groundbreaking for the time, Bonheur was openly a lesbian, living for her whole life with another woman. She also rejected typical female attire and instead applied for a police permit (indicating just how radical this was) in 1852 to wear men's clothes whilst she worked. As such, she sets a precedent and becomes a role model to the likes of the iconic Georgia O'Keeffe and Frida Kahlo, who made similar visual statements of equality in the twentieth century.

- Bonheur diligently studied animal anatomy, often visiting the abattoir and calling such research, "...wading in pools of blood...". The artist's interest in observing the world around her goes deeper than a simple surface sentimentality. The message is that art, like medicine, is a holistic discipline with the scientific impetus to get to the heart of what it means to be alive. How is flesh composed, and how does a body move, and how does that in turn then feel? Bonheur was dedicated to understanding the inner working of creatures in order to successfully convey an exterior view.

- Painted with the accuracy and intricacy of photography before and simultaneous to its widespread invention, her work satisfied an intense craving for Realism at this time. However, there is also a subtle symbolism at work in Rosa Bonheur's pictures. In the way that the artist treats all of her subjects equally, whatever species, be it dog, lion, bull or horse, small or colossal, black, white or brown, Bonheur makes no distinction in terms of value. The underlying suggestion is that she may be a pioneer of racial as well as gender equality, and whether consciously or unconsciously so, a visionary of a better world in which boundaries and binary definitions are entirely dissolved.

- Despite being born a Frenchwoman, Bonheur's work fits particularly well into the English values of the day. Under the reign of Queen Victoria - herself a personal lover of animal paintings - art became homely and easy to understand. The emphasis on literature and philosophy, as well as on art was to adopt a plainer language, and as such engage all people, not only the great and the wealthy. Bonheur's love of storytelling and passion for animals at a time when the British nation was establishing homes for lost and abandoned dogs in Battersea and building pet cemeteries, placed her perfectly in tune, and as such brought fame in her lifetime.

Important Art by Rosa Bonheur

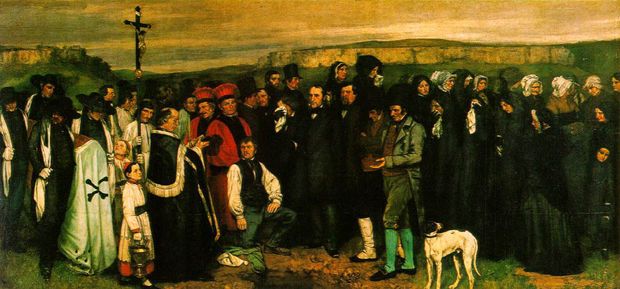

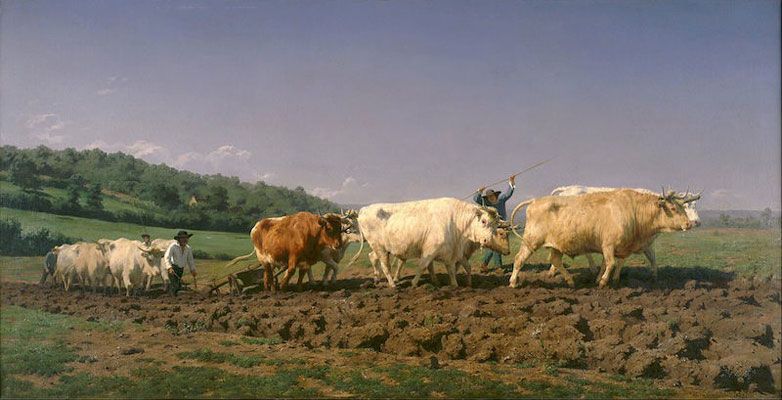

Plowing in the Nivernais

This large oil painting, commissioned and exhibited in 1849 by the French government, was Bonheur's first early success. She primarily depicted animal subjects and here twelve oxen peacefully plough the land in preparation for future planting. Her focus on the land, the animals and the landscape tell a respectful story of timeless peasant life, work, and tradition. The humble sense of realism that emanates from the canvas recalls that work of Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet. Similar to the Realists, Bonheur presents man and nature working seamlessly together to yield harvest from the land.

Bonheur's masterful use of a series of diagonals leads the viewer into and around the sunlit composition. The solid, straight edge of the plowed field recedes from foreground to middle ground. The artist's use of scale and perspective is epic and impressive, and in this sense also recalls the canvases of the Romantics. The two groups of six gleaming Charolais glisten in impressive muscular stride pleasing the eye in their subtle variations of color. The softness, elegance, and muteness of palette also recalls the calm wistful landscapes of earlier Dutch masters, with whose work Bonheur was also very familiar. The artist comments at the time, "I became an animal painter because I loved to move among animals. I would simply study an animal and draw it in the position it took, and when it changed to another position I would draw that."

Oil on canvas - Musée Nationale du Chateau de Fountainebleau, France

The Horse Fair

Bonheur's most famous painting is monumental: eight by sixteen feet. She dedicated herself to the study of draft horses at the dusty, wild horse market in Paris twice a week between 1850 and 1851 where she made endless sketches, some simple line drawings and others in great detail. Her ability to capture the raw power, beauty and strength of the untamed animals in motion is superbly displayed in this dramatic scene. In arriving at the final scheme, the artist drew inspiration from George Stubbs, Théodore Gericault, Eugène Delacroix, and ancient Greek sculpture: she herself referred to The Horse Fair as her own "Parthenon frieze." The Parthenon featured rows of rearing writhing horses in sculpted muscular relief.

The masterful handling of the motion and swirl of dark and light surrounding the pounding, unruly beasts controlled by calm, masterful handlers pulls the viewer into the energy and action of the scene. Bonheur again makes use of a strong diagonal line (as also in Plowing in the Nivernais) in composition where the brooding sky meets the treetops. On the far right, potential buyers calmly look down upon the controlled frenzy from the safety of a wooded hillside. The extremely active middle ground is balanced by the simplicity of the bare foreground and the atmospheric perspective in the background, where we see the outline of the Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital. Although some critics described this work as purely an exercise in academic mastery, it is clear too that the artist is an intense observer of both animal and human psychology. Bonheur writes, "The horse is, like man, the most beautiful and most miserable of creatures, only, in the case of man, it is vice or property that makes him ugly. He is responsible for his own decadence, while the horse is only a slave." It is this painting that brought the artist her first fame outside of her own country as engravings of the scene were transported through Europe and to America.

Oil on Canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

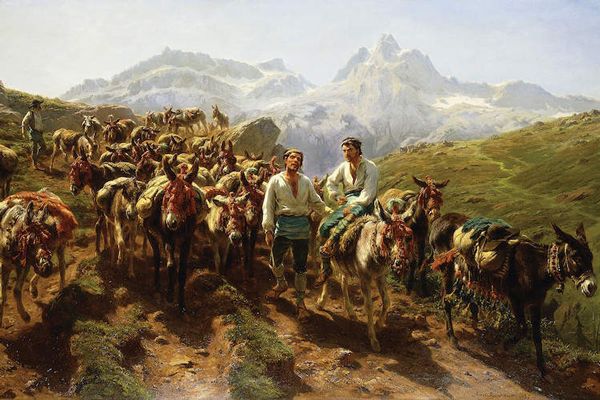

Spanish Muleteers Crossing the Pyrenees

Although the painting is dominated by a dense pack of animals, the dynamic composition incorporates one of Bonheur's most spectacular landscapes. Mules like these were an important means of trade over the mountains; they stream dutifully forward creating a scene of a "Hymn to Work" as described by one critic. The paler distant mountains serve as a backdrop for the artist's "...reverence for the dignity of labor and her visions of human beings in harmony with nature." The bright colors and donkey dressage hints towards more exotic and far away lands in a motif typical of Victorian painters and in particular of Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Attended by three young muleteers, the calmly onward herd fans out across the middle ground in a loosely triangular shape as they descend toward the viewer from a small opening in a craggy pass of the Aspe Mountain. In fact, the entire plan of the composition is made up of triangles created by lines of perspective leading into the central standing figure. The white clothing of the two posed men helps pull the viewer into the middle of the composition, as do the lighter touches of paint on the animals and rutted ground. The attention to details such as the bells and tufted ornaments on the mules bring vitality to the scene. The two distant triangular shapes of misty grey, snowy peaks repeat the design plan. As the biographer Dore Ashton explained, French admirers of the painting praised "...its most glorious and most significant scenery, rendered with a handling akin to old mastership..."

Interestingly here, the protagonist of the scene appears to be a human, whilst all of Bonheur's canvases that follow focus entirely on animals. It is as though the artist needs to show explicitly that she is interested in an interconnectedness between humans and animals in these first three epic canvases, whilst in work to follow she decides that it is when animals stand alone that they convey the strongest messages to humans.

Oil on Canvas - Private Collection

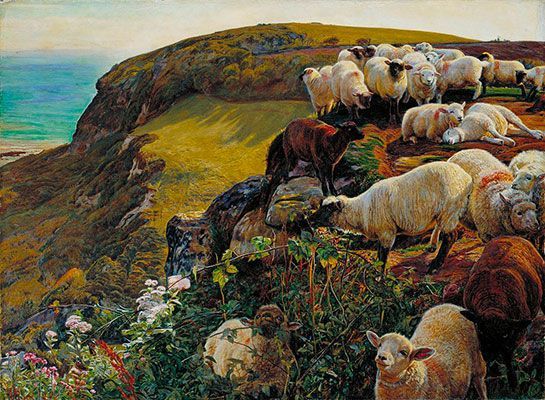

Sheep by the Sea

This small painting, less than thirteen inches by eighteen inches, was painted after a summer trip through the Highlands of Scotland in 1855, a landscape that Bonheur fell in love with. The gentle animals are shown huddled together on the land overlooking a body of water. The artist's dedication to anatomical accuracy and direct observation of nature is evident in the careful details of the animals, the rocks and grasses, as well as the distant seascape. In both scale and subject the work is quite radically different to the artist's previous output. More intimate and without the presence of people, the picture seems to 'say' so much more.

Here we see two ewes and one growing lamb. This family grouping of sheep on the rocks is a subject to which Bonheur returns repeatly throughout her career. A direct parrellel can be made between this work and the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt's Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep) (1852). Hunt's version of the same subject makes symbolism more obvious. The sheep stray to the edge of the cliff, as though in bibical reminder to be a good and moral person. Bonheur leaves her creatures peacefully sitting but it is impossible not to recall righteousness when presented with images of the 'sheep and the goats'. Bonheur perhaps subtlely asserts that 'good' and 'bad' are too stark of assertions, for in her works, two ewes, or a black and a white sheep (in other similar works) live unjudged and harmoniously together.

Bonheur exhibited Sheep by the Sea at the Salon of 1867 although Empress Eugenie of France had commissioned the painting herself. Like her contemporary, Queen Victoria, and also the upper classes of England and France, the French Empress loved paintings of animals. Writer Paul-Louis Hervier said of Bonheur's work in 1908 that it was "...simple, welcoming, of an extreme frankness", and of the artist herself, "she was loved by all; because of her good heart, her generosity, her simplicity, which were not studied but spontaneous... "

Oil on Cradled Panel - National Museum of Women Artists, Washington DC

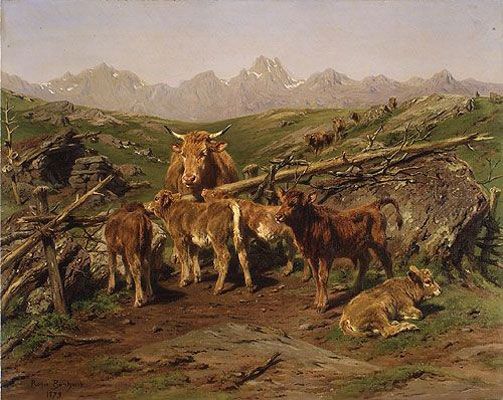

Weaning the Calves

This relatively small painting, less than six feet sqaure, depicts a real life situation in the rustic mountain home of a mother and her calves. The stalwart cow stands watch while her five calves remain separated from her by a barrier of fallen wood, rocks, and debris. The artist shows us a version of fence-line weaning in which the calves see and hear their mother but are forced to find food and water for themselves. The message surrounds the parent-infant relationship and suggests that early independence, even when forced, may in fact be strenghting. The mountains in the background are majestic and in line with Romanic sensibility, whilst the foreground depicts rugged and earthy everyday life for cattle. Bonheur's attention to detail as is typical is impeccable, scientific, and flawless. The endless variations in the rocky land, sharply snapped timbers, and touches of snow present an uncomfortable, barren, and hostile environment, whilst the animals seem alert, patient, and peaceful as they trust in the resolution of their separation.

The painting likely grew from one of the many observational studies created by the artist during her extended trip around the UK in the 1850s. She was in fact criticized by the French art world for her affinity with Scottish and English landscape, especially by Thoré-Bürger, who wrote "...she exhibits ten of her notable works...all belonging to the English aristocracy except the Sheep that the Empress of France has saved from being transported across the sea...After the success of The Horse Fair... pictures have their reddish tone, undecided touch, glassy and mannered effect..." Such criticism did not deter Bonheur from international acclaim for boundaries in any form, national, or otherwise did not interest this inherently open-minded woman.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY

The Lion at Home

From the 1870s onwards, Bonheur began to study and sketch lions and to master the characteristics of their movements. She herself kept her own menagerie of creatures and amongst these she had lions, so the handsome specimens, however exotic, do have grounding in observational reality. There was a thriving foreign animal trade during the Victorian era, and Edwin Lanseer in Britain also had access to and painted lions. This display of unusual animals was typically to parade Empire and show the world that Europe had presence in all far away lands. However, for Bonheur, the interest does not appear imperalialist in any way but more about what it means to be a single lion and what it means to be part of a group. She painted many prides and family sets of lions, but equally lots of striking individual portraits of these commanding and beautiful creatures.

Oil on canvas

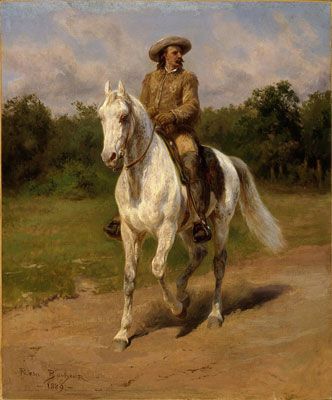

Portrait of Colonel William F. Cody

The artist became very interested in American culture, the native Indians, and the Wild West in her later years. This small painting, less than eighteen by sixteen inches, depicts Colonel Cody or 'Buffalo Bill' on his favorite white horse. Buffalo Bill had come to Paris with his renowned Wild West Show and performed there for more than seven months. Set in beautiful landscape, the scene shows good symbiosis of man and animal, presented as a grand and noble force when working together.

During this time, Bonheur received permission to visit the Wild West Show's encampment, which occupied thirty-six acres near the Bois de Boulogne and the Eiffel Tower. She lept at the opportunity and went almost daily to observe and sketch. She met Colonel Cody and his wide array of performers from all over the world who had thrilled the Parisians. She commented on the show and on the plight of the native Americans "...I was thus able to examine their tents at my ease. I was present at family scenes...conversed as best I could with warriors...made studies of the bisons, horses, and arms. I have a veritable passion, you know, for this unfortunate race and I deplore that it is disappearing before the white unsurpers."

Here the Colonel and his favorite horse are placed in the center and command the composition. The artist's many years of studying the anatomy of the horse and its movement are evident. As the biographer Dore Ashton explained, Rosa advised "...One must know what is under their skin. Otherwise your animal will look like a mat rather than a tiger..." The artist's mastery of brushwork, light and dark and subtle changes in color create a solid dignified portrait. Of the approximately seventeen paintings and countless drawings made of the Wild West Show, this handsome portrait of Colonel William F. Cody on his elegant white horse became the most widely admired and reproduced. The artist gained many American clients and she appreciated the more progressive treatment of women in the United States. Bonheur said, "...If America marches at the forefront of modern civilization...it is because of their admirably intelligent manner of bringing up their daughters and the respect they have for their women."

Oil On Canvas - Whitney Western Art Museum, Cody, Wyoming

Biography of Rosa Bonheur

Childhood and Education

Rosa Bonheur (née Marie-Rosalie) was the oldest of four children, two girls and two boys, born to an idealistic artist father, Oscar-Raymond, and a patient piano teacher mother, Sophie. Interestingly, all four of the children grew to be talented and successful artists. The family moved from rural Bordeaux to Paris in 1829 when Rosa was six years old. She was a rambunctious child who enjoyed sketching as soon as she could hold a pencil, but initially struggled with reading and writing. Her mother helped her to learn basic literacy by asking her daughter to draw an animal for each letter of the alphabet. Rosa recalled "...One day she had a bright idea...She told me to draw an ass opposite the A and a cow opposite the C and so on..." Following her mother's ingenious method, Bonheur always credited her, and this moment in life for her enduring love and deep understanding of animals.

Life in the busy city of Paris was different from the calm country life of Bordeaux. Bonheur's father subscribed to the Saint-Simonian philosophy, which adhered to Utopian socialist values and supported a vision of universal harmony that included total sexual equality. Bonheur recalled "...This was, I believe, the first pronounced step in a course which my father always pursued...named co-education...I was generally a leader in all the games...I did not hesitate now and again to use my fists...a masculine bent was given to my existence..." Oscar-Raymond believed so resolutely in the education and equality of women that he became director for a time of the only available free drawing school for girls that had been founded in Paris under state sponsorship in 1803. After their father's death, Bonheur and one of her sisters took over his position as head of the school.

When Bonheur was only ten a cholera epidemic was sweeping through France. Her father was embroiled in his political and philosophical pursuits and her mother was exhausted. The family did their best to remain indoors to remain free from the disease. Although the children and father all survived, their mother, Sophie fell ill and died at the age of 36.

Bonheur's father attempted to send Rosa to a boarding school run by Mme. Gilbert at this point but the exercise failed miserably, with the artist reporting, "...The Gilberts refused to harbor any longer such a noisy creature as I and sent me back home in disgrace...my tomboy manners had an unfortunate influence on my companions, who soon grew turbulent... " Undeterred by his daughter's unruly behavior at school, Raymond Bonheur decided it better to begin his daughter's art training himself knowing that women were not allowed to attend formal art schools. At this time, he was also studying the writings of George Sands and Felicité Robert Lamennais who both proposed that every creature has a soul, information that he shared with Bonheur and satisfied their mutual respect for animals. At the age of 13 Bonheur began working in her father's studio to complete daily assigned tasks. Her training included pencil drawings of plaster casts, engravings, and still lifes. Once, whilst her father was out, Bonheur embarked on a study of cherries. Upon his return, her father realized the full extent of her talent and encouraged her from thenceforth to work from nature, painting primarily landscapes, animals, and birds.

Early Period

At the age of 14, in 1836, Bonheur's father sent her to study painting and sculpture at the Louvre where she was one of the youngest students. She continued to work in the family studio which she described as "...a confusion of all sorts of odds and ends..." whilst at the same time attending the Louvre where the students copied the Dutch master paintings such as the work of Paulus Potter, Wouvermans, and Van Berghem. When she was 19, her father leased an apartment in which she was allowed to keep a menagerie of small animals: a goat, chickens, quail, canaries and finches. The apartment was located on Rue Rumford, a section of Paris close to fields, farms, and animals, where Bonheur and her three younger siblings could develop their immense talent through realistic drawing and painting. She was said to also frequent "masculine" areas such as horse fairs and the slaughterhouses of Paris in order to gain a deeper understanding of the ranges of animal emotion and physiognomy, however gruesome the latter may have been.

Also in 1842, a friend of the Bonheur family, Monsieur Micas, commissioned her father to paint a portrait of his daughter Nathalie, then 12, who was rather sickly. Although older, Bonheur became very attached to the younger girl and was happily included in the Micas family circle. Nathalie helped the budding artist by tending to her clothing, sewing, and cleaning the studio. Bonheur debuted at the Paris Salon in 1841 with the two paintings Goats and Sheep and Rabbits Nibbling Carrots. From then onwards she exhibited every year until 1855, showing animal studies and landscapes, most influenced by the Barbizon School painters, including Theodore Rousseau and Camille Corot. By 1843 Bonheur was selling her paintings regularly and had enough money to travel the country to study more sheep, cows and bulls.

By the age of 23, Rosa had already exhibited eighteen works at the Paris Salon. Early in her career, she also exhibited sculptures at the Salon, though decided to abandon this as her brother, Isidore, was a gifted sculptor and as his sister she did not want to overshadow him. After Rosa's success at the 1848 Salon (awarded a gold medal), she was commissioned by the French government to create a large painting to honor the tradition of field plowing by animal power. She began sketching for Ploughing in the Nivernais, which was later exhibited at the 1849 Salon. It was also during this year that the artist's father died and she succeeded him as directress of the École Gratuite de Dessins des Jeunes Filles. She also established her own studio with her companion, Nathalie Micas, at 56 rue de l'Ouest.

Mature Period

In 1851, Bonheur established a relationship with an art dealership, the house of Goupil in Paris. Throughout the next years her painted images would be reproduced by Lefèvre in London and Goupil and Peyrol in Paris, disseminating her name and image, thereby increasing her fame beyond the scope of Salon visitors and clients. The pinnacle of Bonheur's artistic career came with the epic painting, Le Marché aux Chevaux (The Horse Fair). The work was started in 1851 and submitted to the 1853 Salon after 18 months of preparatory work. In her book entitled 'Rosa Bonheur: With a Checklist of Works in American Collections', Rosalia Shriver describes the monumental nature of this submission: "When it was finally finished and exhibited at the Salon of 1853, its creator was only 31 years old. Yet no other woman had ever achieved a work of such force and brilliance; and no other animal painter had produced a work of such size."

After the Salon of 1853, Rosa was declared "hors de concours", exempting her from the necessity of submitting further Salon entries for acceptance. She did exhibit Fenaison d'Auvergne (Haymaking in the Auvergne) at the Salon of 1855 for which she was awarded another gold medal. This was her last entry until the Exposition Universelle of 1867. Le Marché aux Chevaux (The Horse Fair) had established Bonheur with secure international fame. Even Queen Victoria invited her to visit at this time. Her trip to England allowed Rosa to meet the President of the Royal Academy, Charles Eastlake, and other British notables including John Ruskin, writer and critic, and Edwin Landseer, the British fellow 'animalier'. She also had the opportunity to tour the English and Scottish countryside in the 1850s where she made studies of the different breeds of British animals to become recurring subjects for her future paintings. Rosa later recalled her travels "...superb country in spite of its melancholy mists; for I prefer what is green...I love the Scotch mists, the cloud swept mountains, the dark heather - I love them with all my heart..." When she returned to Paris, Rosa was confident of her work and secure economically.

After the 1850s, a prosperous middle class grew in England. These were people eager to have art in their homes, and as such artists benefitted. An art dealer of the epoch, Ernst Gambart, purchased many original paintings and also their copyrights in order to make reproductions. Gambart established a close working arrangement with Bonheur among other artists. Bonheur's continued financial prosperity encouraged her to set up a new studio. The Micas family supervised the studio's development whilst Bonheur concentrated on collecting a selection of animals that she wanted to live with. As the critic Armand Baschet described in 1854, "...[the] window of her studio, with superb light, faces this courtyard where her heifer, her goats, and her sheep, as well as her mare, Margot, can live freely...add...all the fowl of a Normandy farm...". Occasionally, Bonheur's zeal for unusual animals caused calamity within the family. She brought back an otter from the Pyrenees trip which caused despair whenever "...it had the bad habit of leaving the water tank and getting between the sheets of Mme. Micas' bed" recalled Bonheur's brother-in-law.

In spite of her own busy career, Bonheur and her sister, Juliette continued to teach at École Gratitude de Dessins des Jeunes Filles, the drawing school founded by their father. Rosa designed a course called "the science of drawing" based upon her father's style of direct observation. She also welcomed important socialites to her studio and other artists at this time, and especially her lifelong friend, Paul Chardin. Chardin knew that the British appreciated Bonheur's work greatly and that she in turn admired British artists. In 1903 Chardin wrote, she "...especially admired Landseer...she had quite a quantity of superb engravings from the canvases of this artist..." After 1855, French critics became disappointed by Bonheur's seeming lack of interest in the salons and in France, whilst the English aristocracy now bought most of her works.

Overall, Bonheur found the interest in her life and experience of intensified fame quite distressing. As result, in the summer of 1859 she retreated from Paris and found and bought a chateau, a house and farm, in the tiny village of By, near the Fountainebleu Forest. She built a large studio as well as many pens for her growing collection of animals, and settled back to work there with Nathalie and Mme. Micas.

Late Period and Death

Bonheur was extremely happy in her secluded existence in the village of By. She usually began her day at dawn, walking to find a suitable place in the forest where she could work until dusk. She saw fewer other artists than in previous years, except for Chardin who remained a dear friend and often came to sketch. In the evenings, Bonheur and her close family and friends would smoke cigarettes together and chat by the fireplace. She was extremely surprised to be visited by the Empress Eugenie on June 15, 1865, when she was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, long since established by Napoleon. Nathalie Micas remained Bonheur's loyal, calm, and constant companion. After Nathalie died in 1889, Rosa grieved heavily as she related to a friend "...how hard it is to be separated...for she had borne with me the mortifications...she alone knew me, and I, her only friend, knew what she was worth."

By 1893, Rosa had recovered some of her characteristic energy and traveled to the United States for a tour of the Women's Building at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. A young American female artist had contacted the artist in 1889 and asked to paint her portrait but Rosa did not feel up to the task at the time. Following her return to France from America however, she was feeling better and able to meet with Anna Klumpke who was a portrait and genre painter from Boston. As a student, Klumpke had studied in France and copied Plowing in the Nivernais for an assigned task. Klumpke was already fascinated by Bonheur and had owned a "Rosa" doll when she was a child. Over a very short time, the women became captivated by one another. Bonheur offered Klumpke a living arrangement at By which they both signed in August 1898. Klumpke agreed to paint several portraits of Bonheur as well as write the older artist's biography. As a writer, diarist, and painter, Klumpke became the official portraitist and companion of Bonheur in the last years of her life. Klumpke completed three portraits before Bonheur's death on May 25, 1899, and in 1908 she published 'Rosa Bonheur: Sa vie et son oeuvre' (Rosa Bonheur: Her Life and Works) based on Bonheur's personal diary, letters, sketches and other writings.

Klumpke, in spite of the disapproval of both her own family and Bonheur's, managed Bonheur's estate for the rest of her life. Since Bonheur had named her the heir of the estate, Klumpke presided over the sale of 892 paintings and numerous other artworks, selling most in 1900 for 72 million francs. In 1924, Klumpke opened the Musée Rosa Bonheur in By, and established the Rosa Bonheur Memorial Art School which would offer art instruction to women. In 1940 Klumpke published 'Memoirs of an Artist' and died in 1942. Her ashes were later entombed alongside Rosa Bonheur and Nathalie Micas in Père Lachaise cemetery.

The Legacy of Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur became a commercially successful painter at a time and place when few women were successful at pursuing a career in the arts. Europeans of the nineteenth century considered art to be a lady's pastime pursued at her home but due to her father's training and influences, Bonheur approached her artwork as her profession. Bonheur's staunch belief in women's equality and her unconventional personal habits, which included wearing men's clothing at work, riding her horse astride, and smoking identified her as an early feminist.

By painting animals and not women themselves, Bonheur's influence upon other women artists seems to skip a generation and jump straight into the twentieth century. Artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, who followed Bonheur directly in timeline, mainly depicted the limitations of domestic existence in a remaining patriarchal world. It was the likes of Georgia O'Keeffe and Claude Cahun of the early-twentieth century who rejected constructed expectations and binary gender roles absolutely, to the extent that they created art that they wanted to, and not work simply to reveal that they were still caged. These women wore men's clothes to show that it was about time that their achievements were equally assessed, and remarkably, Rosa Bonheur had this same attitude as the female artists of the twentieth century who collectively, in time, radically shifted and changed the freedom and rights of women.

Unconventional in her lifestyle, Bonheur painted with academic rigor but her methods of working en plein air were still relatively unusual for the day. She admired the Barbizon School in France and many members of this group painted their landscapes outdoors. However, the majority of artists working during the nineteenth century were still studio based. Especially towards the end of her career, Bonheur always took her canvas and easel outside, and in this act she influenced the next radical turn and movement in art history, that of Impressionism. The likes of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro advocated the en plein air technique in order to achieve true likeness and capture the most beautiful light, and such were the ideals shared with the ever forward thinker, Rosa Bonheur.

Influences and Connections

- George Stubbs

- Antoine-Louis Barge

- John Louis Gericault

- Karl Bodner

- Constant Tryon

-

![Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin]() Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin - Nathalie Micas

-

![Realism]() Realism

Realism -

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism - Landscape Painting

- Anna Klumpke

- Molly Luce

- Wayne Theibaud

- Robin Becker

-

![Realism]() Realism

Realism -

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism ![Feminist Movement]() Feminist Movement

Feminist Movement

Useful Resources on Rosa Bonheur

- Rosa BonheurOur PickBy Rosalia Shriver

- Rosa Bonheur - A Life and a LegendOur PickBy Dore Ashton

- Reminiscences of Rosa BoheurBy Theodore Stanton

- Women Painters of the World - free eBookBy Walter Shaw Sparrow

- Women Artists: An Illustrated HistoryBy Nancy Heller

- Nineteenth Century ArtBy Robert Rosenblum and HW Janson

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI