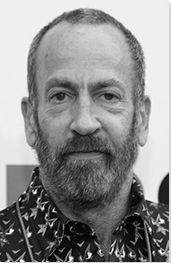

Summary of Kenny Scharf

Like many kids growing up amongst Pop Art's cultural explosion in the 1960s, Kenny Scharf was heavily influenced by the images of popular and commercial culture that infused and informed American collective consciousness. But unlike most kids, Scharf's obsessions would extend beyond cutting out photos from magazines to pin on his bedroom wall. Instead, he gleefully found expression on the streets, where, with spray paint can in hand, he could share his distinctive, Day-Glo, psychedelic illustrations with the people. Mixing joyous visuals bred from a decidedly Southern California upbringing awash in cartoons, muscle cars, sunshine, and the burgeoning possibilities in space travel and future technologies, he was pivotal in transforming the public's perception of graffiti from a low brow form of illegal mark making into the viable medium of art it is today.

From his roots on the West Coast through later immersion into New York City's seminal East Village art scene, Scharf brought his animated visions to the public, contributing to a new Street Art lexicon that continues to position itself an equal player on the contemporary art world's main stage.

Accomplishments

- Scharf's passion for infusing the "everyday" with art would spill over into every aspect of his life where no object was sacred. From walls to household appliances to cars, no surface escaped his ebullient expressions. In his world, everything is alive with creative energy and his work continues to accentuate this notion.

- Although originally influenced heavily by the iconography of his youth and upbringing, Scharf's style has evolved into an unmistakable and signature look marked by bold, illustrative lines and comic cosmic characters that seem to inhabit their own playful worlds in which fun is the underlying impetus.

- Scharf has defined his cartoony world as a way to articulate emotion. Growing up in a world that vacillated between societal tragedies such as the AIDS crisis and the Cold War and the optimism of scientific and technological advancements, his work allowed him to process society's communal feelings in a way that ultimately provoked joy.

- Like one of his Art Brut heroes, the French artist Jean Dubuffet, Scharf believes that true art derives from an internal impulse to "make," rather than a conscious drive to pursue art as a career. Even as his own success has catapulted, Scharf remains committed to this concept, seeing art as his essential mode of being rather than a strategized ambition.

The Life of Kenny Scharf

Cartoony and cosmic, the psychedelic world of Kenny Scharf delivers spray paint infused joy for the people from the streets.

Important Art by Kenny Scharf

Escaped in Time, I'm Pleased

This work comes from a series of paintings called "The Death of Estelle," painted in a style that recalls realist 1950s commercial advertisements. The series, when viewed in sequence, tells the story of a "jet-set woman of the future" with brightly colored hair and clothing that directly references the fashion from the futuristic TV cartoon series The Jetsons. In the series, Estelle is enjoying a pizza party when she is approached by extraterrestrials who emerge from her television to tell her how to travel into space. In Escaped in Time, I'm Pleased, the fifth painting in the series, Scharf explains that Estelle is "inside the space ship and she's looking out the window and she sees the world exploding in a nuclear explosion. And she's pleased [...] she's fine as long as she got away."

Visual studies scholar Natalie E. Phillips asserts that this series, as well as several of the works Scharf created throughout the 1980s (often adopting imagery and characters from The Jetsons) was his response to the fear and anxiety that pervaded American society at the time due to the Cold War and the threat of nuclear holocaust, Ronald Reagan's "strong doomsday rhetoric," and the sobering reality of the AIDS crisis. Phillips writes that Scharf's work "vacillates between opposites (good vs. bad, heaven vs. hell, parody vs. sincerity), refusing to occupy a fixed position," and that it is rife with "odd juxtapositions [...] between the horrific and the benign [which] are the artist's means of coping with his own apocalyptic anxiety, as well as a critique of the self-destructive behavior of American society."

Phillips asserts that in this work "The horror of the mushroom cloud she views from space is mollified by Estelle's cheery smile and the mediation of the explosion through the television screen. Like Scharf himself, Estelle is the ultimate escapist. The Estelle paintings help allay anxiety by trivializing nuclear holocaust, transforming it into a gleeful, nihilistic celebration. Estelle's fashionable, non-stop interplanetary party is seductive. Yet the obvious absurdity of her nonchalant response to the demise of the planet simultaneously underscores Scharf's intentionally ridiculous, escapist desire to dodge Earth's problems by simply moving to outer space."

Acrylic on canvas

Judy

In Judy, one of Scharf's earliest graffiti murals, we see a crudely-drawn version of Judy Jetson from the futuristic cartoon The Jetsons, executed in red spray paint on a white brick wall. Here, Judy's head is atop a one of Scharf's signature swirling cosmic shapes, giving her the appearance of flying. A comic strip speech bubble near her mouth contains a small squiggle as if to denote an unimportant comment.

What mattered most for Scharf in his early graffiti art was not so much what the work said, as its placement in a public space. This attitude would go on to inform Scharf's career for the next several decades, as he believes that art should enter into and coexist with, rather than be separated from, everyday life.

Friend and artist Keith Haring shared with Scharf his interest in Art Brut and the theories of French artist Jean Dubuffet, who asserted that true art derives from an internal creative impulse rather than a conscious drive to pursue art as a career. This attitude led Haring and Scharf to develop a strong interest in the subway graffiti of New York City, to become friends with graffiti artists like DAZE and HAZE, and to begin creating their own graffiti works. Scharf explains, "I never professed to be a graffiti artist, nor a street artist either. I just found that hitting the street was the best way to get out there. Especially living in New York City, where all these art people weren't interested in looking at my work or accepting me in a gallery. I wanted to confront them, I wanted them to have no choice but to see me."

Spray paint - New York

Cosmic Cavern 2

In 1981, at the same time he began creating unsanctioned graffiti in public spaces, Scharf also had the urge to decorate interior, private spaces with what he coined "Cosmic Caverns." He first had the idea when he came across a black light, and placed it in a small closet in his East Village loft. He proceeded to fill the room with a variety of brightly colored "junk" (like appliances and toys), and to paint the walls in fluorescent colors. He says that at first, "People didn't look at what I was doing as very original because black light was very popular in the '60s with the hippie culture. In the '80s, it was kind of weird to bring something back that was already from another generation. But I didn't care. I loved and I still love what black light does to a space." The installations became immersive, psychedelic, multi-sensory environments that he has since re-created in various venues.

The Cosmic Caverns were largely informed by Scharf's lifelong "fascination with junk and garbage." He explains, "I had been making art out of trash for awhile before that. I like appliances and things with dials and toys, things I can transform into these science fiction/fantasy objects." He also notes, "When I moved to New York in 1978, the city was basically a trash heap. And I found it fascinating because there was so much great stuff. As punk rock and new wave kids, we were finding all this cool 1950s stuff which we were inspired by and allowed us to both mourn and make fun of the 'death of the American dream.'"

Scharf later recreated the Cosmic Cavern on a larger scale at Club 57, a popular hangout and dance venue for artists like FUTURA 2000, Klaus Nomi, Ann Magnuson, Andy Warhol, and FAB 5 FREDDY. Scharf explains, "parties started happening in them. I love having art that you can dance in. It becomes alive. Visual art itself is alive, but when you have music and people, it's a great performance. [...] Art is so solitary that when you get to do something involving a party and a bunch of people it's great."

Day-Glo paint, PS1 - Long Island City

Vacuum

As part of his desire, in the early 1980s, to imbue everyday items and environments with an artistic element, Scharf customized a wide variety of found objects and "broken junk," including household appliances and toys. His favorite of these customized found-object works was this vacuum, painted to look like a cartoonish red and green cyclops he named "Cheeki." He referred to Cheeki as his "pet," and explains, "It was kind of similar to how the Flintstones had their pets as appliances. So, I took this vacuum cleaner, made it into my pet, and then would actually take her for walks on a leash. It was really fun."

In this way, Cheeki became a sort of performance piece. Scharf recalls, "One day I took Cheeki for a walk in the Garment District, where guys would regularly run around with clothing racks and pieces of plywood on wheels, and I remember one of them suddenly stopped and looked Cheeki and I over, then our 'pets' sniffed each other, and we just kept going."

Repurposing junk has been an important artistic and environmentally-conscious activity for Scharf throughout his career. He says, "Whether it's a car, a TV, a telephone, anything that you actually use and handle and touch, if you turn that object into art, then you bring art into your everyday life. I look at it as futuristic but also it's very ancient. I compare it to the Ancient Egyptians or the Greeks. All their objects that they used in their daily life were art."

Scharf has customized a number of other found objects such as Answering Machine (1982). He explains, "I was customizing all these broken appliances that I'd find in the street, and then one day I decided, why only do broken ones? I should do ones that are still working and then it'll be even more transformative." Years later, when exhibiting Answering Machine at a group show, he pressed play on the recordings, and discovered a message from his deceased friend Keith Haring. Scharf says, "It was very bittersweet and really touched my heart."

Customized vacuum cleaner

Untitled

In 2009, Scharf was invited to contribute a mural to the Houston Bowery wall, part of the Wynwood Walls, a "museum of the streets" begun in conjunction with Art Basel Miami Beach. The massive epitomizes typical Scharf style, with brightly colored, interlocking, goofy faces and characters, arranged centrally around a red oval, which serves as the nose of a jagged-toothed, macabre creature. Arts writer Sandra Schulman asserts, "Maybe [this snarling face] represents some omnipotent force, an angry cartoon god that all the other characters swirling around him need to needle, poke, chomp on."

When he returned to the site in 2010, he was devastated to find that his mural had been tagged over. He says, "I had a really tough time after doing that wall. It's such a high-profile space, and there are so many writers that want to get on it, and a lot of them don't know who I am. I come from a different world and time, and, well, let's just say they annihilated it." That winter, he painstakingly tried to restore the mural, saying, "It was freezing, very difficult to see what was underneath and much more difficult than initially painting it. So there I was, looking at somebody's big, ugly tag and trying to bring back what was there. It was 100 times harder than doing the original mural."

When the restoration process was put on hold because of a blizzard, Scharf returned to find that the wall had been bombed again. When he expressed his frustration on Internet graffiti blogs, he received strong negative responses from a younger generation of artists who were unaware of Scharf's early involvement in the Wynwood walls, which they viewed as belonging to them. He says, "They were, like, threatening to kill me. Yes, it's the Internet; yes, people say a lot of crazy shit. But it was clear they didn't know or care about their own history."

Spray paint - Houston Bowery (Wynwood Walls), Miami

Untitled

Typical of Scharf's oeuvre, this large mural painted on the side of a parking garage features a swirling mass of brightly-colored cartoon faces in a joyful, cosmic soup. Scharf usually paints smiling figures, explaining, "I want to feel that happiness and joy. It makes me happy if I make a perfect smile." He also notes that his characters can be likened to animated "emotions."

Scharf's decision to paint cartoon-like figures is a conscientious one. Even in his early career, "I thought to have cartoons in the art world is a no-brainer. I'm not the first one that did it. I mean, pop artists were doing it, and I thought that ground was broken way before me. Yet I encountered a lot of resistance, and maybe because my cartoon use wasn't ironic. [...] I think that people a lot of times didn't like that. They thought it was kid stuff, and I wasn't being a serious adult artist." Yet Curator Richard D Marshall suggests, "Disguised as lurid, Day-Glo colored cartoon heads; Scharf's subjects present a surreal, yet achievable reality of a harmonious cohabitation of man, nature and the cosmos."

When executing large-scale murals like this, Scharf works solo, without assistants, aided only by the driver of the cherry-picker lift that helps him reach all parts of the surface. He explains that "It's just spray paint and nobody can really help you. And I make it up on the spot, I don't really know what exactly I'm doing anyway, so how could I... You know, it's not color-in like you can have someone else do it for you." He views his artistic process as analogous to that of a jazz musician "who has all of their repertoire, their notes, their tricks, you know, they learned it, they're good musicians. And they have kind of an idea of where they're going to go, but they kind of go [where they want to take you]".

Spray paint - West Hollywood, California

What Me Worry? (Blue)

What Me Worry? (Blue) is comprised of several slim, goofy-looking, red and grey figures that resemble sperm, as well as small spheres, and other organic forms, superimposed on top of a collage-like jumble of newspaper headlines and articles about global warming. The wacky, oblivious expressions of the figures, in contrast with the frightening and dire text in the background, serves as a criticism of the way in which humankind refuses to take seriously the imminent threat facing our planet.

In recent years, Scharf has created multiple works that deal directly with environmental issues like climate change and pollution. Scharf, who vividly remembers growing up amidst the perpetual smog days of Southern California, recently stated, "I feel that I can't be quiet about my obsessions which have always been our environment and the danger to our fragile ecosystem. I have been making this my main focus pretty much with all of my messaging either blatant in your face or underlying and subtle, but it's always there. Lately, I feel the need to utilize all of the dire headlines we are all confronting on a daily basis as we enter the most dangerous and stressful moment in our ecological human history."

The sperm-shaped references to human reproduction in this work relate to Scharf's concern for his children, and for all of the future generations inheriting a damaged planet. On one hand, he feels a sense of impending doom, noting that today's children are "so innocent and pure and what the fuck is going to be there for them? Sorry, there's no animals, they're all extinct." Yet at the same time he communicates his fear through this and similar works, he also makes sure to include "messages of hope and optimism and joy," in order to inspire viewers to take action, rather than resigning themselves to a hopeless future.

Oil, acrylic, silkscreen ink and mylar on linen with aluminum frame

Biography of Kenny Scharf

Childhood

Kenny Scharf grew up in the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley, north of Los Angeles, California. He was raised Jewish, and attended a Hebrew elementary school, which he hated. He was much more inclined toward the contemporary pop culture climate. Art historian and critic G. James Daichendt asserts that, because of Scharf's L.A. upbringing, "the importance of hot rod culture, van art, album covers, punk music, along with all the futuristic architecture of southern California's imagined future played a huge role on his aesthetic." His parents supported his interest in art from a young age, taking him to visit museums and galleries.

Scharf was born the same year as the first satellite Sputnik was launched into space. He recalls, "In school, when they told us that by 1984 we would be able to get on our own rocket and fly to the moon, I believed it." He spent his childhood fascinated by the parallels between the macro- and micro-cosmos, saying, "A solar system looks and acts the same as a proton and a neutron in an atom, the electrons rolling around, just like planets rolling around the sun. It's pretty amazing when you think about how inner space goes on to infinity, as does outer space."

Scharf was fascinated by television, especially after his parents bought their first color set when he was seven years old. He loved cartoons like The Jetsons, which he says, "sparked all my obsessions with cars, jets and the American Dream." Although he adds, "as enticing and wonderful as these images are, I always felt like they were somehow selling our impending doom. Gas-consuming, smog-producing petroleum - it's our liberation and our destruction."

At the age of fourteen, Scharf transferred from public high school to Oakwood, a "hippie" private school in North Hollywood. At a party in ninth grade he smoked marijuana for the first time, and has continued to use the drug almost daily ever since, preferring it to alcohol or other substances. He recently stated, "I think if everybody was on cannabis instead of other freaky drugs, everybody would be in a much better place."

Education and Early Training

After one year of college in Santa Barbara, where he fell in love with Andy Warhol's work in an art history class, Scharf moved to Manhattan as he believed it would be a more conducive environment to starting an art career. He received his B.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts in 1980 with a major in painting. While studying in New York, he learned from teachers like Judy Pfaff, Elizabeth Murray, and Barbara Schwartz.

During college, Scharf became close friends with his roommate, another young artist named Keith Haring, and the two began experimenting with creating unsanctioned graffiti in the city's streets and subway lines. Scharf and Haring were also part of a larger group of seminal artists, including Jean-Michel Basquiat, who translated the graffiti aesthetic onto canvas, showing their work at the Post-Graffiti collective show at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1983.

Critic Grace Glueck responded negatively to the Post-Graffiti show, calling it "unsettling," and writing, "Apart from its illegality, the very idea of enshrining graffiti - an art of the streets impulsive and spontaneous by nature - in the traditional, time-honored medium of canvas, is ridiculous." Scharf was defensive, however, and encouraged his fellow graffiti artists to familiarize themselves with the "hierarchies and culture of the American fine-art system." He explains, "I said, 'You should study some art history, because you're entering this other thing now.' The ones who made it were usually the ones who did."

Scharf developed his own personal style, which he calls "Pop Surrealism," using Krylon spray paint in Day-Glo colors to create psychedelic, cosmic images. He also experimented with creating sculptural assemblages out of household appliances and ephemera, like televisions, answering machines, and plastic toys. These works perplexed his professors, as well as mainstream gallery owners, limiting his potential exhibition venues to smaller independent galleries like the FUN Gallery (1981) and the Tony Shafrazi Gallery (1984), as well as unsanctioned public spaces like city streets and subway lines, where he executed colorful, large-scale murals.

As was common with the artists of the East Village Art scene of the 1980s, Scharf turned himself into a spectacle, for instance, walking down Broadway with his "pet" vacuum cleaner. Scharf found the period to be extremely liberating, noting that "You could be in a band, you could be a performance artist, you could be a painter, you could be a filmmaker, all at the same time. There was nobody saying, 'You need to focus on one thing.'"

In 1983, Scharf and then-wife Tereza (a yoga teacher whom he met while on vacation in Brazil) had their first daughter, Zena, and a few years later, a second, Malia. He later stated, "I was way too young to know what I was getting involved with, but I was 25. 25 thinking I was a full on adult and I should have a child. But now I have grandkids from her, so it was all worth it. [...] I'm so happy. I'm so lucky and blessed." Zena now works in the art department of fashion photographer Patrick McMullan. Malia is now an actress and artist, who has collaborated with her father on projects including a clothing line titled Scharftees.

Mature Period

It wasn't until the mid-1980s that Scharf started to find recognition within larger institutions, when he was invited to participate in the 1985 Whitney Biennial. Five years later, he decided to stop painting in the streets, turning instead to acrylic paint, in part because his health had been affected by years of inhaling spray paint, and because he was devastated by the death of Basquiat (due to heroin overdose) on August 12, 1988, and the AIDS-related death of Haring on February 16, 1990. Scharf recalls, "Even though we were making money and successful at that time, it just wasn't as fun because we didn't get to enjoy it when people are dying. [...] It's kind of hard to celebrate your success when people or friends are dying."

Scharf's friendships with Haring and Basquiat in the East Village Art scene of the 1980s were a foundational aspect of his art career. He says of Haring, "Keith was a very close friend of mine. We shared a space together up by Bryant Park. [...] became my daughter's Godfather. We were very close. He was one of the most important people in my life... he still is." The slew of deaths in Scharf's community gave him a sense of survivor's guilt. He says, "I felt like I was being punished for not dying with the rest of my group."

Scharf's relationship with Basquiat was more tumultuous. He explains that he and Basquiat "used to go around the streets together and we had a very, kind of, intense relationship. And then it kind of soured [...] He would sabotage me all the time, and then apologize. I would be so happy that we were going to be friends again, and then the very next day it was as if that never happened and he just treated me the same. [...] And then we kind of reunited towards the end, right before he died."

In 1993, Scharf decided to leave New York. He relocated his family to Miami for six years, before returning to Los Angeles in 1999, and then back to New York in 2000, where he lived in Brooklyn for five years. In 2005, he chose to settle permanently back in Los Angeles, in a home just above fellow artist Ed Ruscha's studio, in the Culver City area. He explains, "When I would open [my door] in Brooklyn, [there] would be trucks banging. And then in my yard in LA, I have, you know, hummingbirds. I was like, hmm, why do I want to live up there?"

More recently, Scharf reflected on the major moves he has made in his life, stating, "New York will always be my city. My desires, dreams, and ambitions were shared by like-minded young minds in a strategic time in our evolutions as artists. Growing up in LA shaped much of my visual language. Living back here where I grew up feels good and allows me to be connected to the art world, yet I am much closer to the sky, trees, and the Pacific Ocean. [...] Now I live a few blocks from my grandkids so I am not going anywhere far away for too long!"

Scharf has been involved in a number of pop culture collaborations. In 1986, he created the album cover art for the album Bouncing off the Satellites by the B-52s, his "favorite band ever." He recalls, "When I first saw them, I was like, 'Oh my god, this is the musical counterpart to my art'. [...] I felt very connected immediately. All I wanted to do was to do everything for them." In 1987 and 1997, he collaborated with Absolut Vodka. In 2012, he created designs for Fendi purses and Kiehl's cosmetics.

At a 2004 retrospective of his work at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, Scharf requested to paint the 10,000-square foot parking garage, which now stands as a permanent, spray-painted installation called the Kosmic Krylon Garage. In 2011, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles held the first major museum retrospective of graffiti, titled Art in the Streets, for which Scharf re-created his Cosmic Cavern of the 1980s.

Scharf became frustrated by the MOCA trustees' disdain of the type of visitor that was attending the show. He says, "The people who came to the Art in the Streets show were not the people buying tables at the gala dinners. Sometimes I think museums would rather remain ghost towns than pack the place with people that make them feel uncomfortable. The art world looks at art for the people as dumb art, but I see it differently. [...] Let's bring up the masses. Let's help people smart up."

Scharf continues to paint, both on canvas, and in the streets. When doing public works, he prefers to paint alone, using acrylic Montana Gold spray paint, without assistants. He says, "I knock out these murals in two, three days. Sometimes when I get there, there are these younger artists working on their own murals. They've been there two weeks and they've got crews with them, and then I walk in and I'm just like, OK, I'm done, goodbye. I like to be able to show the kids that getting older doesn't mean you become any less powerful." Scharf's daughter Malia recently said about her dad, "At this point in his career he is able to reach more people than he has ever reached before. [...] There are few artists who were born knowing nothing but to create and Kenny is a rare example."

The Legacy of Kenny Scharf

As one of the few surviving key artists of New York's East Village art scene of the 1980s, Scharf has managed to carry on the unique attitude originally embodied by the group. In particular, he has made it a priority to create art that is part of everyday life, by blending art with useful objects like appliances and clothing, and by painting murals in the streets as well as in spaces like children's hospitals and event venues, with the intention of creating images that add to the overall experience and enjoyment of a pre-existing environment. He says, "Part of what I do and what I want to do is to bring art into the everyday life. If you're just walking in the street and you're confronted by something, that might change your day - it might inspire you." Recently, this has meant Scharf's creation of custom facemasks in response to the coronavirus pandemic, which feature the colorful mouths of his cosmic characters that add a dose of levity to the act of social distancing.

As arts writer Demetria Daniels notes, Scharf's oeuvre also serves as a prominent example of the potentially powerful role of hope, joy, play, and optimism, and a sense of love in contemporary art. Despite being criticized at times for creating pop-like imagery without any real conceptual depth, art historian and critic G. James Daichendt asserts that Scharf "will leave the world a much brighter and unique place to live. His artwork [...] is part of his desire to spread joy and happiness. Kenny likes to have fun and wants his artwork [...] to have the same impact on viewers. It's hard not to smile when you see it."

Daichendt also recognizes that Scharf's other significant impact on the contemporary art world has been his role in bridging the gap between illegal graffiti and street art culture and the institutional art world, and in opening dialogues regarding perceived dichotomies such as insider/outsider, and high/low art. Daichendt writes, "These accomplishments also transitioned into commercial products and customizing boring everyday objects with Kenny's unique aesthetic. These ideas abound today by contemporary street artists - so its no wonder why he's considered one of the grandfathers of the movement." Many of today's most famous and successful artists, like Banksy, Zevs, and Jeff Koons, share in Scharf's sentiments, creating works that straddle the boundary between consumer culture, lowbrow art, and fine art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Banksy]() Banksy

Banksy -

![Jeff Koons]() Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons - Malia Scharf

-

![Street and Graffiti Art]() Street and Graffiti Art

Street and Graffiti Art - Lowbrow art