Summary of Henry Hobson Richardson

Richardson is amongst the few architects to have had a particular style named after them. At a time when the more ornate Romanesque Revival style had come to define modern American architecture, Richardson drew his influence from the more orderly Romanesque designs associated with the southern European churches built by French, Italian and Spanish pilgrims in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. He combined his "solid and heavy" medieval-like exteriors with an innovative modern take on interior space, and in doing so he found a combination that saw America put down its own marker on the timeline of Western architectural history. The "Richardsonian Romanesque" style, as it became known, lent itself to a wide range of building types and proved a formative influence on some of the country's greatest architects including Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and John Wellborn Root.

Accomplishments

- Following on directly from the American Romanesque Revival of 1840-60, the Richardsonian Romanesque style is generally accepted to have been America's first uniquely original trend in architecture. The extravagant earlier revival style had unconditionally embraced ornate European Gothic trends, but Richardson's more sober designs were still flexible enough to assimilate less ostentatious ornamental details including polychromed walls, decorative friezes, Syrian arches, and overhanging roofs.

- The Romanesque Revival took the best qualities of classical Roman architecture and blended these with elements of "Gothic" stylization such as conical roofs; asymmetrical facades and incongruous stone and brick façades. The Richardsonian Romanesque style introduced a more refined, more elegant age of American architectural design that could be applied to buildings ranging from churches to town halls; railroad stations to libraries; court houses to domestic dwellings.

- Richardson emulated the aesthetic of the medieval style by focusing on thick stone walls and through a preference for sturdy arches. Indeed, the original Romanesque structures were solid and heavy and Richardson's civic buildings were also muscular and imposing. But he proved himself to be much more than a revivalist with his interiors earning him added distinction for their innovative and orderly spatial organization.

- Rather than the uneven massing (massing being an architectural term that relates to how a building's exterior relates to its interior) that defined Gothic architecture, Richardson insisted on harmonious massing. His famous design for Sever Hall at Harvard University, for instance, drew special admiration for the way it balanced and ordered its striking red mortar façade with a functional, general purpose interior.

- Towards the end of his career, Richardson presented modern Americans with a sweeping reworking of domestic homebuilding that was characterized by a shift towards the more modern style of open planning. Making full use of advances in construction materials, Richardson pushed his stronger, thinner, exterior walls to the edge of the property thus allowing for more spacious, light-filled, domestic residencies. One might even cite Richardson as an early advocate of the "form follows function" maxim that guided some of the twentieth century's most important modernist architects and designers.

The Life of Henry Hobson Richardson

With a short career that amounted to "One of the great unfinished poems of American cultural history", Richardson was, according to the art historian John Russell, "one of America's lost leaders"; a pioneer of a post-Civil War nation who "almost singlehandedly brought architecture from its position as hardly more than a subdepartment of contracting to the very front rank of the professions".

Important Art by Henry Hobson Richardson

H.H. Richardson Complex

First known as the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, the Richardson Olmsted Complex was built over an eight-year period after Richardson had won the commission in 1871. Describing its most eye-catching features, author Francis Russell notes that the, "sturdy, twinned towers [that] rise naturally from a structure [have] precisely the amount of jut and thrust that was needed. Corner turrets look spontaneous and not stuck on. The sweeping entranceway, consisting of three round arches, deep-set between projecting side bays, prevents the eye from moving uninterrupted upward. Hip-roofed dormers rehearse the forms of the towers and turrets. Lintels and colonnettes between the dormers show a finesse of detailing [then] new to Richardson's work ". Many of these elements were inspired by the Romanesque style of medieval Europe and the complex provides the first example of the so-called "Richardsonian Romanesque" style.

This work is also significant because it was the largest commission Richardson would receive in his short career. With so many elements to incorporate into a single complex, and because it was built to accommodate and provide the best surroundings for those battling severe mental illness, Richardson worked in conjunction with other design experts and medical professionals to provide a holistic environment. One of the contributors was Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect of New York's Central Park and the Buffalo park system, a lifelong friend (and former assistant) of Richardson, who designed the grounds for the complex. His input led to the building being oriented to the southeast thus maximizing it exposure to daylight. This strategy, combined with the red sandstone and brick central administration tower block, and the five wards set back on each side, produced a more open, spacious site that offered a more considered and humane environment for treating patients than had been seen in America hitherto.

While the building's function has changed, first in 1927 when half of the complex was given over to Buffalo State College for campus use, and more recently in its conversion into a hotel and conference center, Richardson's original building, remains, according to the Richardson Olmsted Campus website, "one of Buffalo's most important and beautiful buildings ". This boast was confirmed in 1986 when it was awarded the official status of National Historic Landmark.

Buffalo, New York

Trinity Church

The Trinity Church on Copley Square in Boston is one of the great monuments in the history of American architecture. Trinity was an Episcopal Church that by 1869 had outgrown its old central Boston location and plans were afoot to relocate the church to the city's more affluent Back Bay area. This need to move was accelerated when the original Trinity church fell victim to Boston's Great Fire of 1872. The rector of Trinity, Phillips Brooks, was one of the great preachers of the day and it was he who pushed for the relocation on a tract of land facing Copley Square.

What would become one of Richardson's most iconic buildings, it became a crowning example of Richardsonian Romanesque styling and it is the first building in which the architect introduced his preference for rough stone (an estimated 90 million pounds of stone were used), his signature arches and, in this example, an elegant series of towers.

With the Trinity Church, Richardson had introduced American worshipers to a new style of church architecture. According to the architectural historian James F. O'Gorman, Richardson, "scrapped his first sketches, which called for a classic design typical of Gothic Revival Episcopal churches of the time, and, instead, sketched an unconventional Greek cross plan [...] This approach represented a radical departure for American ecclesiastical design. It presented an inclusive, open auditorium plan closer in spirit to the emerging needs of democratic contemporary American congregational practice, than to the hierarchical, conventional Episcopal designs and worship practices of the day". Indeed, Richardson followed Pastor Brooks's commitment to a "more honest" style of church, and in so doing Richardson had unwittingly provided a paradigm for future church designs.

What is perhaps most characteristic about the Trinity Church is the equal attention Richardson paid to all aspects of the building. As Francis Russell described it, visitors to the church would, "marvel at the way the exterior hints at the mysterious contents within ". Richardson had succeeded in creating what he termed a "color church" and to do so he turned to partnerships with other leading artists. According to Francis Russell, "Richardson was determined that the interior would be alive with color, a decision that led to his collaboration with various artists, including Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Englishmen William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, and John LaFarge, who was responsible for the murals and stained glass. What Richardson wanted was nothing less than for the spirit of the age to take up residence in Trinity Church ". He succeeded in his task, and in so doing created a building that remains one of the most important and treasured in the Boston cityscape.

Boston, Massachusetts

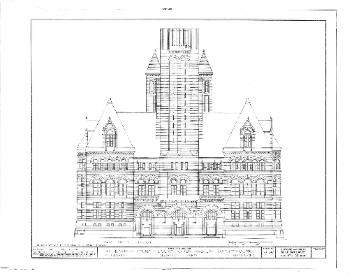

New York State Capital

The New York State Capital building was arguably one of the most complicated collaborative commissions in which Richardson played a leading part. Over the course of the thirty-two years it took to complete this building, Richardson was a member of one of three different teams of architects who worked on the project and as such the building can be viewed as a collage of styles. This period saw him collaborate with architect Leopold Eidlitz and took place between 1875 and 1883.

The first team of architects had begun to build the capital in a classical Roman Renaissance style. When Richardson took over, he made additions in his Romanesque Revival style. This, according to Van Rensselaer, caused widespread "indignation at the thought of seeing in a single building a union of two different styles ". Undaunted, Richardson persevered and added key elements to the building including the governor's and court of appeals rooms. The most notable of his contributions was, however, the senate chamber. As it is described in detail on the New York State Assembly's official website: "this room has been acclaimed as one of Richardson's finest designs. Beginning at its highest point, the chamber's richly carved golden oak ceiling was designed with deep paneled 'pockets' or recesses, creating an acoustically perfect 'debate arena' for the senators. The walls are covered with beautiful, shimmering 23 carat gold leaf. A master at using the different materials of the world, Richardson imported Siena marble from Italy for the large arches above the visitor's gallery, red granite from Scotland for the pillars, and Mexican onyx to panel the north and south walls. The ultimate in luxury was attained with red leather and carved mahogany paneling on the walls below the galleries [...] At the back of the chamber are two large fireplaces, each with openings six feet high ".

Learning first-hand the difficulties often associated with government commissions, Richardson was dismissed when governor Grover Cleveland began his term in an attempt to curb what he felt were escalating building costs. Describing the difficulties associated with this job, Van Rensselaer states how it was for Richardson, "the only time in his life [that he was] publicly in opposition to other members of his profession".

materials - Albany, New York

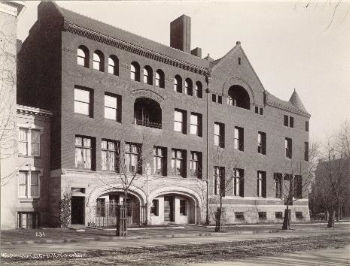

Sever Hall, Harvard University

A work created for Richardson's alma mater as a classroom building, it is, with its two curved bays, grand arch entranceway and exterior detailing, the purest celebration of the Romanesque Revival style. This was the first work Richardson designed after the dissolution of his partnership with Charles Gambrill and thus represents his true independence as an architect. As Van Rensselaer states, "Sever Hall was designed at the period when Richardson had just given himself over, heart and soul, to the leadings of southern Romanesque art, and when the exuberant possibilities of this art had recently seduced him somewhat from sobriety. Therefore, its singular simplicity and its paucity of pronounced Romanesque features bear strong witness to the development of his feeling for appropriateness as a prime architectural virtue ".

The building also provides a clear example of Richardson's role as a master colorist. Choosing to substitute his preferred gray stone with red brick added to the building's New England character. Francis Russell states, "in contrast to the vigorous and extroverted character of so many of his eclectic constructions, Sever Hall has an aristocratic aloofness and perfection of detail that are all the more striking for being executed entirely in red brick. Red mortar and orange-tiled roofs complete the chromatic motif, which was no doubt adopted out of deference to Harvard's older buildings ". The building earned the admiration of the prominent American architect Robert Venturi who went so far as to call Sever Hall his "favorite building in America ". Indeed, Venturi, who preferred to think of architecture in terms of a functional "generic shelter" rather than as "abstract-expressive sculpture", spoke of the Richardson's design in quasi-poetic terms when he said, "I love Sever Hall [...] for its aesthetic tension deriving from its vital details. I could stand and look at it all day. Thank you, H.H. Richardson ".

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Connecticut River Railroad Station

Richardson was commissioned to design a number of railroad stations for the Boston and Albany Railroad company, a prime example of which was the Connecticut River Railroad Station. His single-story buildings were variations on a basic symmetric layout featuring a pair of waiting rooms, and an outsized roof designed, in part, with Japanese architecture in mind. With its rugged granite exterior, arched windows, brownstone trim, and hipped hanging roofline (modelled on a temple in Nikko) would come to rank as a signature Richardson design. Of the interior design, the author Derek Straham described how "the central part of the station included the main waiting room, which occupied about half of the ground floor [and that there] was also a separate ladies' waiting room, and a room that, on the original floor plans, was labeled 'Emigrant's Room' [which was] used to screen and administer smallpox vaccinations to incoming immigrants, who comprised a large portion of Holyoke's population during this time. Other facilities inside the building included a baggage room, a ticket office, and a telegraph office, along with several restrooms ".

At this time in his career, with his star in the ascendence, Richardson could have turned down relatively modest projects like this. Van Rensselaer felt in fact that, "it is much to be regretted that Richardson was never commissioned to build a great terminal railway station [and that] success with smaller stations proves that such a problem would have given free outlet to his talent on its strongest side ". Nevertheless, it was Richardson's sheer love of the nuances of architectural design than was paramount in his thinking and he "put on no airs about which projects he took". Van Rensselaer adds that for Richardson "every structure, even the most basic, should be not only functional but also aesthetically pleasing" and that in this example "the drinking-fountains, gas-fixtures, the settees on the exterior and the long benches within, and the ticket-offices which project upon the platform as charmingly designed bays " all confirm Richardson's attention to detail.

It is a sad footnote to record that Connecticut River Railroad Station has suffered from serious neglect since its closure in 1965 and, save for a period after this when it was converted into a gas station, it has been left abandoned.

Holyoke, Massachusetts

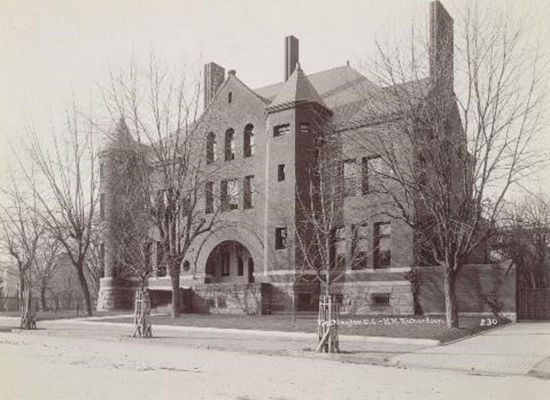

John Hay Residence

An interesting personal project, Richardson was commissioned to build adjoining houses for two leading Washington, D.C. dignitaries and their families: the prominent historian, and man of letters, Henry Adams, and the prominent politician John Hay. Adams was the great-grandson of John Adams and the grandson of John Quincy Adams, both former presidents of the United States, while Hay served in key government roles including President Abraham Lincoln's personal secretary, and secretary of state for both Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. The two men's status brought added kudos to Richardson's house and helped bolster his already impressive reputation. Following the death of both men, their respective families sold the properties on to a developer in 1927 who converted the building into the now iconic Washington landmark, the appropriately named Hays-Adams Hotel.

Van Rensselaer notes that, "the finest external feature of Mr. Hay's house is the doorway on Sixteenth Street - an imposing arrangement of broad steps leading up to a balustraded platform with a richly carved door set back under a powerful round arch. Inside, even the fine hall is exceeded in beauty by the dining-room, one end of which is filled by a wide mantel of green marble recessed in a deep alcove of the same material ". Overall, the Adams/Hay building is an important example of the impressive domestic residences Richardson designed towards the end of his life. But, as Van Rensselaer observed, in his early career Richardson had had a "comparative distaste for domestic work [and he] would sometimes exclaim in his over-emphatic way that 'house-building is not architecture in the noble sense of the word'". However, commissions for domestic dwellings increased in number as his reputation grew and in "the last years of his life he felt the deepest concern and the most entire pride in the many houses he then had in hand ".

Washington DC

Allegheny County Courthouse

A complex combining a courthouse and jail, surround by a spacious courtyard, Richardson's Allegheny County Courthouse flaunts its debt to European medieval architecture. Richardson pays homage to the European style predominantly through the high tower, the heavy solid gray stone bricks, and the rows of windows topped with arches which are framed by fake columns.

The courthouse features three main floors of courtrooms, city offices, and a library, with the five remaining floors located in the tower and intended for the sole purposes of storage. According to Dr. Charles L. Rosenblum, Richardson's "design refers to the Roman Aqueducts, Syrian monasteries and Roman Renaissance palaces, while providing master classes in stone detailing and grand stairway design " also adding that "the Bridge of Sighs, connecting the Courthouse and Jail, may even surpass the beauty of the Venetian structures that inspired it ".

Richardson was awarded the commission in 1884 and, once completed, the Courthouse dominated the city of Pittsburgh's landscape as no structure had before. Among his greatest achievements, this building confirmed his reputation as America's leading architect. Sadly, Richardson did not live long enough to see it open to the public (in 1888) but he had already claimed the building was his favorite design. Indeed, aware of the seriousness of his health conditions, he often told others of his desire to see the project fully realized and was convinced it would be his crowning achievement. Richardson stated: "if they honor me for the pigmy things I have already done, what will they say when they see Pittsburgh finished ".

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Marshall Field's Wholesale Store

A seven-story building - three of which are below ground - Richardson's gray stone structure was created to be used as the wholesale store for the iconic Chicago Marshall Field's department store empire. By the time Richardson designed this building he had become famous for his revival of the medieval Romanesque style and there are obvious elements of that style here; most notably in the curved arches above the windows. These stylistic flourishes are, however, much less pronounced than in his earlier works. Noting this fact, Van Rensselaer describes the structure as a "vast rectangular box in its most uncompromising estate", adding that the whole "site measures three hundred and twenty-five feet by one hundred and ninety feet, and every foot is covered by a solid mass which rises to a height of one hundred and twenty-five feet. The roof is invisible, the doorways are inconspicuous, and decoration is very sparingly used. The whole effect depends upon the structure of the walls themselves. No building could more frankly express its purpose or be more self-denying in the use of ornament ".

This structure provides a glimpse of the direction his future architectural style might have taken had he survived his illness. According to author Francis Russell, "though stark in comparison with some of Richardson's more flamboyant buildings, the Field store is not lacking in detail. But the overtones of medieval splendor had been dropped, and in their place, Richardson had achieved what he called 'a careful study of the piers and a perfectly quiet and massive treatment of wall surfaces'". The fact that he could modify his style to reflect and support the use of the building shows his maturity and foreshadows the more modern aesthetic that would develop in American architecture in the following decades. Sadly, the effects of modernization also impacted the building when in 1930 the store was relocated and Richardson's building was demolished. The original store was the inspiration for Louis Sullivan's Auditorium Theater.

Chicago, Illinois

Biography of Henry Hobson Richardson

Childhood

Henry Hobson Richardson was born on his maternal family's sugar cane farm, the Priestly Plantation, in Louisiana. Born into privilege, his father Henry Dickenson Richardson hailed from Bermuda, while his mother, Catherine Caroline Priestly, came from a distinguished scientific family that included Dr. Joseph Priestly, known for his discovery of oxygen. Richardson enjoyed a happy childhood. He was educated at a private school where, according to author Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer, by the time he was ten years old "his love for drawing induced his father to place him, with pupils of much greater age, under the best master in New Orleans; and in mathematics he was exceptionally proficient from the very first ". According to author Francis Russell, meanwhile, his prodigy extended to downtime activities too: "he was bright enough to be able to play several games of chess at once while blindfolded".

Early Training

Following his father's death, Richardson was intent on honoring his wishes by enrolling in the prestigious West Point military academy. He was denied admittance however due to a speech impediment; it was, according to Francis Russell, "a rejection that left a lasting mark on his psyche ".

After a year at the University of Louisiana, Richardson enrolled at Harvard University. His college years were happy, making many friends who, according to Van Rensselaer, gave him the moniker "'Nothing to Wear,' from the fact that he had better clothes and more of them than any other one man needed ". Harvard provided more in terms of personal contacts than intellectual stimulus and Richardson moved freely within the Universities various social circles, including membership of the Porcellian Club which secured him several influential contacts. It was while at Harvard that he became engaged to his future wife, Julia Gorham Hayden. He would remain loyal to his college, ultimately designing two of the university's buildings: Sever Hall (1878) and Austin Hall (1881).

Having briefly contemplated a career in civil engineering, Richardson settled on becoming an architect and, following graduation, his step-father supplied him with the funds to study architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris between 1860-62. Helped by the fact he spoke fluent French (due to his Louisiana upbringing), Richardson's admittance to such a prestigious school was an impressive personal achievement. As Francis Russell explains, "at his first attempt at admission, in the fall of 1859, he failed in descriptive geometry, a subject he had been introduced to only four weeks before. But in November 1860, he came eighteenth in a field of 120 - and only the second American (after Richard Morris Hunt) to win admission ". While in Paris he became conversant with the analytical architectural theory formulated by his professor Julien Guadet, and the style of Beaux Arts Architecture - with its preference for ornamental and sculptural designs, arched entranceways and windows, and structural solidity - which was itself an amalgamation of the best aspects of the European Baroque, Gothic, and Renaissance styles.

While he enjoyed living in France, his carefree days as a student came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the American Civil War. The war had a profound impact on his family's financial situation and Richardson was left to fend for himself in a foreign land. As Francis Russell observed, Richardson, "went from being one of the richer young Americans in Paris to one of the poorer, obliged to work for his living. Though optimistic by nature, he had a difficult time ". To support himself he gained work in the offices of the French architect, Théodore Labrouste.

Despite having to adjust to his unwelcomed situation, Richardson was highly motivated and fully dedicated to his studies. Writing to his fiancée in 1862, he wrote, "study and society are incompatible [...] I hardly have time to take my meals [and] I intend studying my profession in such a manner as to make my success a surety and not a matter of chance", while adding that, "every day I find new beauties in a profession which I already place at the head of all the Fine Arts ". One of Richardson's most treasured memories of his time in Paris came from working on his own projects in the atelier of architect Louis-Jules André. It was the comradery with fellow students, and the guiding influence of André, that left the deepest impression on Richardson and he would try to recreate the same working environment when he established his own Massachusetts studio several years later.

Richardson returned briefly to America in 1862 but with the Civil War raging he could not venture homeward to the south. He considered looking for work with friends in Boston, but, on the advice of his mother, he chose instead to return to Paris to wait out the war and to advance his studies. Though it proved to be his best option, it caused Richardson considerable compunction. He recalled, "I burned with shame when I read the capture of my city and I in Paris". In order to earn money, he supported his studies by working at the Hospice des Incurables pour Hommes, a French hospital for the terminally ill.

Mature Period

With his education completed, and having earned the distinction of being one of the first Americans to graduate from the Architectural Section of the École des Beaux-Arts, Richardson returned to America in October of 1865 (after the four year Civil War). Choosing not to settle back in the South (in fact he would never return to New Orleans again) he opted to make his home in New York City. His earliest days on the East Coast saw him struggle to find work; his situation was made more difficult with the death of his mother. Despite these setbacks, Richardson maintained his dapper dress-sense. As Francis Russell explains, early on in New York "he had to sell the collection of architectural tomes he had bought at Harvard, and before long he was down to his last dollar, though still conspicuous in his English suits, his English shoes, his stylish cravats, and his strong and still-slender build. Somewhere, somehow, he had to make an impressive beginning as his own master ". Indeed, he received his first commission in November of 1866 (at the age of thirty) for a Unitarian church in Springfield, Massachusetts. On learning that he had been awarded the commission, Van Rensselaer records that Richardson "burst into tears and exclaimed, 'That is all I wanted - a chance ".

This commission revived his spirits and gave him the confidence to think he could actually make enough money to support a family. He married Julia Gorham Hayden in January 1867 and they settled in a home, of Richardson's own design, on Staten Island. His nearest neighbour was the journalist and landscapist Frederick Law Olmsted with whom he would collaborate on later projects. His marriage was lasting and happy and the couple would raise six children together.

In 1867, shortly after his first commission, Richardson entered into partnership with the architect Charles Gambrill with whom he founded the firm Gambrill & Richardson. He began taking on important commissions including several churches, public libraries, the State Capitol building in Albany, and a state mental hospital in Buffalo. It was through Gambrill & Richardson that he ushered in the revival in the medieval Romanesque style he had studied and admired while studying in Europe. It was a style that would eventually bear its own name: Richardsonian Romanesque: a less dramatic, more subtle and rounded - more American - approach than the popular European Gothic style. The author Dr. Jackie Craven notes the architectural features Richardson employed included "square stones, round towers with cone-shaped roofs, columns and pilasters with spirals and leaf designs, low, broad 'Roman' arches over arcades and doorways, patterned masonry arches over windows [and] medieval details such as stained glass".

Richardson spent a great deal of time focusing on the finer interior and exterior details of his buildings. According to Van Rensselaer, "he was among the first American architects to preach and practice the fundamental precept that when walls and roof are standing a building is not finished, but still needs that its builder should concern himself with every detail of its decoration, perfecting it himself or calling upon other artists to perfect it in a way harmonious with his own results. No feature was too small, no object too simple to engage his thought ".

While based in Manhattan, Richardson produced designs for the State Asylum for the Insane in Buffalo, the Brattle Square Unitarian Church and the Trinity Church (both in Boston). The original Trinity Church had been the charge of the famous preacher Phillips Brooks and was already considered one of the most important Episcopal churches in North America. Richardson's design earned him many admirers and, as his reputation grew, many of new commissions came in from the Massachusetts area. As a direct result, the Richardson family relocated to the town of Brookline (just outside Boston) in the spring of 1874. Richardson's next significant move was to dissolve his partnership with Gambrill. According to Van Rensselaer's account, "the ties of the partnership had so relaxed that when they were severed in October, 1878, no public announcement of the fact was made. Richardson's offices were now also removed to Brookline and accommodated under the same roof with his home; and here, amid singularly advantageous and congenial surroundings, he lived and worked during the eight years that remained to him ".

His first solo commission, for the Sever Hall, his alma mater, amounted to a "statement of intent". According to Francis Russell, Richardson duly "surrounded himself with the cream of Brookline society, an ideal society in which he himself was the center [...] Neighbors and visitors from out of town crowded into the house on Sunday afternoons to listen to quartets playing Haydn and Beethoven and to look at the designs that were on display ".

On a professional level, too, his home suited him well. He hired assistants Stanford White and Fredrick Law Olmsted, both of whom would go on to find fame in their own right, and took great pleasure in schooling new students. As Francis Russell explains, "Richardson created in Brookline the atmosphere of the Parisian ateliers he had known in his youth, infused with the same spirit of hard and selfless work, an uninhibited exchange of ideas, and communal feasting. Richardson was more than simply a mentor to his assistants: [he] was father, teacher, employer, playmate, and god. Architecture was not all they learned from him. In all his dealings, he was a model of civility, though he demanded nothing short of their best. He gave them the run of his library and his tennis court, (though not for more than thirty minutes during a work day) the benefit of his life experiences, and the best of his food and wine ".

Unfortunately, Richardson's life was not without its impediments. He developed an obesity problem that saw him weigh in at well over three hundred pounds. According to Francis Russell, "his obesity was a symptom of Bright's disease, or chronic nephritis, a deadly malfunction of the kidneys. As he aged, his energy progressively grew more and more limited, and he knew he could not count on a long career ". In describing the limitations that this disease placed on Richardson, Van Rensselaer adds that, "often he was kept for many days at home by its attacks or actually confined to his bed; and he gradually grew so very stout that his weight alone might have been thought an almost prohibitive obstacle to bodily exertion ".

Later Period

So dedicated was he to his business, Richardson only took one overseas vacation, a trip to Europe in the fall of 1882. In part, this voyage was planned so that he could consult with doctors in London about his health; though he also visited France, Italy, and Spain. While taking in the architecture of Western Europe, he also enjoyed a visit with William Morris in his studio. Despite a lack of resolution to his health problems, the trip proved a pleasant gastronomic and aesthetic diversion which he confirmed in a note home, "I feel as if I were being mentally and sentimentally stuffed with pâté de foie gras, and expect to have an artistic indigestion for the rest of my life".

Upon his return to America, Richardson threw himself into his work with an intensity that belied the fact that he would only live for four more years. He worked intently on, and was most enthused by, his last two major projects: the Pittsburgh Courthouse and the Field Building in Chicago. Suffering repeatedly from health relapses, he told colleagues that he wished more than anything, "to live two years to see the Pittsburgh Court-house and the Chicago store complete ".

In the last years of his life, Richardson turned his attention to designing domestic residences and felt, according to Van Rensselaer, "the deepest concern and the most entire pride in the many houses he then had in hand ". These more modest (in scale) structures, which included a series of small railroad stations throughout the North East, provided most of Richardson's late-career commissions.

In the sure knowledge that his health was deteriorating, Richardson never took life for granted and worked as if each day might be his last. According to Van Rensselaer, "it was only a few weeks before his death that after a tour of his crowded offices he paused to say: 'There is lots of work to do, isn't there? And such work! And then to think that I may die here in this office at any moment [and concluding that] 'there is no man in the whole world that enjoys life while it lasts as I do' ".

In March of 1886 Richardson became sick with tonsillitis followed by a flare-up of his more chronic condition. Despite warnings to relax his workload, he travelled to Washington, D.C. to oversee works in progress. When he returned home he suffered a relapse and died two weeks later aged just forty-seven. With so much potential and years ahead of him had he been healthy, one can only speculate on what he might have achieved.

Richardson died, at the height of his powers and with major works in Boston, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Ohio, Chicago and St. Louis still under construction. Summing up his impact on American architecture, the art historian John Russell wrote the following: "Everyone agrees that Richardson in his last years took on more work than he himself could seriously oversee. But he had something to say, he had not long to live, and he had a very good staff. Besides, he did not wish to fall short of the role that had been thrust upon him; that of Mr. Architecture. From being an obscure beginner on Staten Island, he had risen in hardly more than a decade to being the most talked-of architect in America. And he held that place: in 1885 American Architect and Building News took a poll as to what were the ten finest buildings in the country. Five of them were by Richardson, as it turned out, and Trinity Church, Boston, came at the top. Who can blame him if he wanted to redefine the potential of American architecture before he died?".

The Legacy of Henry Hobson Richardson

In his short (twenty-one-year) career, Richardson succeeded in leaving his indelible mark on the history of modern American architecture. According to architect William Morgan, he remains "widely regarded as one of the giants of American architecture. Both a prophet of the future and a remnant of the past, he became the leader of the revival of Romanesque forms that bears his name, while at the same time his powerful buildings and imaginative use of materials influenced the generation of modern architects that succeeded him ".

His style can be located in the designs of former employees Charles Coolidge and George Shepley, and other luminaries including Frank Alden, Fenimore Bates, Herbert Burdett, Harvey Ellis, Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow, and George D. Mason. Indeed, the leaders of the Chicago School of Architecture, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, took inspiration from his style. As the architect William Morgan notes, "unlike so many of his contemporaries, Richardson was able to conceive of a building as a whole and to maintain its integrity throughout, regardless of decorative features. This 'organic' approach was one of his principal legacies to Sullivan and Wright ".

A strong part of Richardson's legacy lies also in his role as a mentor and teacher. He influenced the careers of many modern architects including Stanford White and Fredrick Law Olmsted, both of whom thrived under his tutorage. He also helped shape the careers of the many students he brought into and worked with in his studio. While his career was cut short by ill health, his ideas and respect for the nobility of the field of architecture, and what it could be in a modern, independent, America, lived on in the designs of those he influenced.

Influences and Connections

![Edward Burne-Jones]() Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones- Louis-Jules André

- Charles Gambrill

- John La Farge

- Théodore Labrouste

- Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer

-

![Louis Sullivan]() Louis Sullivan

Louis Sullivan ![Edward Burne-Jones]() Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones- Charles Gambrill

- John La Farge

- Frederick Law Olmsted

- Henry Van Brunt

- Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer

![Modern Architecture]() Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture- Richardsonian Romanesque architecture

- Romanesque Revival architecture

Useful Resources on Henry Hobson Richardson

- Henry Hobson Richardson and His WorksOur PickBy Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer

- The Architects: Henry Hobson RichardsonOur PickBy Francis Russell