Summary of Sergei Eisenstein

Eisenstein's early 20th-century experiments with radical montage techniques demonstrated to the world that cinema could do more than "merely" entertain the masses. His dialectical editing technique offered a counterpoint to the smooth continuity editing model that was the pillar of the globally dominant Hollywood style. By juxtaposing (rather than unifying) individual shots, Eisenstein showed that film montage could be used to rouse - or "agitate" - his audience. In line with the dogma of the Constructivist movement, Eisenstein had conceived of a modern artform that was fit for a new Soviet society. However, his relationship with the Soviet state grew strained under the rise of Stalin, and the dictator's decree that the official state art should adhere strictly to the tenets of Social and Socialist Realism. Eisenstein's ideas carried a deep theoretical basis, with his writings, published in English towards the mid-century, passing down to future generations of Western filmmakers.

Accomplishments

- Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925) boasts one of the most analyzed sequences in the history of cinema. Through his staging of the massacre of civilians on the steps of Odessa, he offered a concise (six minute) masterclass on how montage could be used to jolt and provoke an audience into political consciousness.

- Eisenstein's "montage of attractions" was based on the principle of the Marxist dialectic. Shot A: thesis, is juxtaposed with shot B: antithesis, which results in C: synthesis. This dynamic, which pays little heed to the rules of cinematic verisimilitude, insisted on an intellectual engagement from the audience. By piecing the disparate shots together for themselves, the spectator would, in theory, become intellectually empowered.

- Eisenstein developed five stages of montage - metric, rhythmic, tonal, over tonal, and intellectual - that combined and clashed to bring an energy and dynamism to Soviet cinema. While these editing strategies may have shed their political impetus, they have been widely (if a little more sparingly) adopted by many key western filmmakers.

- Eisenstein's use of montage was closely aligned with the idea of agit prop (agitational propaganda). The term was applied to Constructivist artworks that aimed to animate and educate its audience in the Bolshevik cause. While his relationship with the state was ambivalent, his earlier films, such as Strike (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), and October (1927) were instrumental in promoting the idea (albeit short lived) that the culture of the new Soviet Union would be represented through the languages of the avant-garde.

The Life of Sergei Eisenstein

Historian Ann Nesbett writes, "Eisenstein is never clearly one thing over another, never philosopher enough or fool enough to be easily categorised, and his political attitudes, too, resist pigeonholing even as they seem to invite it".

Important Art by Sergei Eisenstein

Battleship Potemkin (Odessa steps massacre)

Battleship Potemkin was Eisenstein's second feature film (after Strike but released in the same year). Divided into five acts in the manner of a classical tragedy, the film is based on a mutiny that took place during the First Russian Revolution of 1905. The crew of Potemkin rise up against the imperial regime, and the ships officers who have (amongst other acts of cruelty) served them maggot-infested meat. The ordinary people of the Black Sea port of Odessa learn of the mutiny (a red flag, hand tinted in an age of monochrome film, is raised in support of the revolution) and come out onto the streets of Odessa in an act of solidarity with the sailors that would prove fatal.

Although based on fact, the film remains best known for a fictional scene that has become one of the most influential in the history of cinema: the Odessa Steps massacre. Lasting approximately six minutes, we see citizens fleeing down the steep steps as they are systematically mown down by Cossack troops. Eisenstein uses his radical editing techniques to maximize the emotional impact of the onslaught. The scene features jump cuts, close-shots, cross-cuts, wide angle shots, and a mix of static and tracking shots. For example, Eisenstein creates tension by using a mixture of close shots and tracking shots focused on a baby carriage that teeters on the lip of one of the steps as baby's mother is knocked down. Another woman gasps in horror as she watches the pram tumble down the steps, gathering momentum as it goes. The radical use of editing - which creates tension by extending time rather than condensing it (in the manner of a classical Hollywood storytelling) - widened the vocabulary of film grammar.

The film also differed from Hollywood cinema in that it did not feature a hero whose job was to carry the plot. Eisenstein focused rather on the masses. Indeed, most of the performers were not professional actors at all but were chosen to represent "types" (this method of casting became known as "typeage"). Vassilieva noted, "While working on Battleship Potemkin he had already started to figure effectiveness as pathos, a term which in his usage not only retains its traditionally positive, indeed heroic, Russian connotations but also becomes loaded with the additional function of transformation and re-orientation of the viewer. [Eisenstein] had not only created a most impressive picture of revolutionary martyrdom [he] had also shown that political art could be moving and still remain art. The film projected a new understanding of cinema and a different type of hero - the masses".

October (Ten Days That Shook the World)

Commissioned by Stalin to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917, the film is a historical restaging of events leading up to the point when the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government through an uprising in Petrograd (led by Vladimir Lenin). Eisenstein approached the project as an opportunity to experiment with his editing style rather than a full commitment to historical accuracy. Indeed, while the film is now widely considered to be Eisenstein's magnum opus, at the time of its release the film was widely criticized for its narrative incoherence.

Released as October in the Soviet Union (with the subtitle Ten Days that Shook the World added for international release), Eisenstein was afforded all the resources and permissions he asked for, including official authorization to film at the actual locations of the historical events. Filming at the Winter Palace, for example, Eisenstein described the palatial residence of the Tzars, as an "unbelievably rich cinematic material. Its own electric station. Wine cellars. Reception rooms. One bedroom is worth 300 icons and 200 porcelain Easter eggs. A bedroom that no contemporary psyche could stand". In the presence of such overwhelming extravagance, Eisenstein newly perceived the absurd perversity of imperialism and felt that his intellectual montages could ruthlessly undermine such a grotesque display of riches.

New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) writes, "Eisenstein's grandly orchestrated film of the Russian revolution [...] remains one of his most ambitious attempts to find a form for his theories of montage and their philosophical possibilities. [October] is one of the supreme examples of how an insurrectionary political will might be combined with an equally radical aesthetic program". The eminent American poet, playwright, art connoisseur, and patron of the arts, Lincoln E. Kirstein, referred to October as "among those classics that theaters would continually hand down to history, year after year, like Shakespearean repertory". Kirstein even published a poem dedicated to the film: "from Lenin's earthquake, - / His battles in Eisenstein's lens: Winter Palace attack: / Crowds tearing across squares, a rein on demoniac / Mobs, one mad rush, each step on its ordained track: / Power assayed, controlled, arrayed, - then hurled // At our bedazzled eyes, - / In live amazement now, / Since everywhere, wherever movies are shown, / Still Eisenstein lives his double lives in our history. / Cineastes often swear he used news-clips: mystery / Of double-imagery. Myth or allegory, / Founded in fact, for as fact his films are known".

Que viva México!

In 1930 Hollywood's Paramount Studios offered Eisenstein a film contract. Eisenstein explored several projects, though creative differences with the studio became quickly apparent. The Paramount offer fell through, but Eisenstein had already been introduced to Charlie Chaplin who, in turn, introduced him to the novelist Upton Sinclair and his wife, Mary. The Sinclairs had formed the "Mexican Film Trust". In late November 1930, Eisenstein signed a contract with the Sinclairs to make an hour-long non-political film which he would complete within four months. Eisenstein's interest in Mexican culture had in fact begun in 1922 in his role as designer on a theatrical production of The Mexican (derived from a short story by the American writer Jack London), and later after meeting Diego Rivera in Moscow at the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution.

Unlike the (failed) Paramount feature-film proposals, the Sinclairs were primarily interested in a kind of artistic travelogue. However, Eisenstein conceived of the Que viva México! as an anthology, containing four novellas each focused on a doomed romantic coupling at different eras in Mexican history. The film would be framed by a prologue placed at the time of Mayan civilization and an epilogue placed in a Day of the Dead celebration in modern Mexico. The director explained his intent, "This was the history of cultural changes, but not presented vertically - in years and centuries - but horizontally: as utterly diverse stages of culture, coexisting in the same geographical area, next to each other".

The film was never completed by Eisenstein who was recalled to Moscow in 1932. He had hoped to edit the film in the Soviet Union, but the footage remained in the United States with the Sinclairs. They handed Eisenstein's footage over to the independent producer, Sol Lesser, who edited the footage as, Thunder over Mexico (a tale of young ranch hands who are victimized by a hacienda owner), and two short films, Eisenstein in Mexico, and Death Day (all 1933-34). Eisenstein was horrified with the results and described Thunder over Mexico as "pitiful gibberish". In 1978, Eisenstein's former assistant, Gregori Aleksandrov, cut a version of Thunder over Mexico in an attempt to fulfil his friend's original vision. Aleksandrov worked with Eisenstein's correspondences and journals, but critics and scholars continue to debate the extent to which the newly-edited material would have met with Eisenstein's approval. That reservation notwithstanding, others, such as silent film critic Fritzi Kramer, have championed the film through "Eisenstein's ability to find natural beauty in the buildings, dress, clothing and features of ordinary citizens [and] the regal beauty of the agave and the banana trees that dot the landscape".

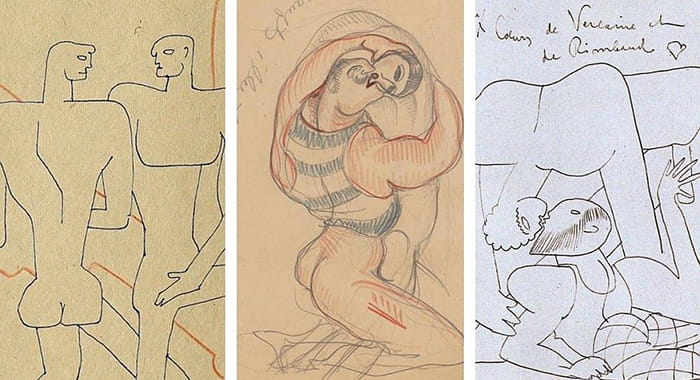

Untitled drawings

Each of these three drawings depicts a couple in an intimate clinch. On the left, two nude men are depicted, though they are strikingly alike with their square shoulders and almost geometric forms, and only their intersecting legs and gazes reveal their attraction. In the center image, a masculine figure, wearing only a figure-hugging vest, embraces a woman energetically, though the woman's body is loosely outlined. Only her face is clearly depicted as her head is turned sideways, so the emphasis remains primarily on the aggressive energy of the male form. The angle at which her head is turned resembles that of the kissing heads in the third image. Here, an inscription references the love affair between the poet Verlaine (represented by the bearded man) and Rimbaud, the younger man leaning over him.

This emphasis on primordial sensuality is found in many of Eisenstein's drawings. Eisenstein wrote, "It was in Mexico that my drawing underwent an internal catharsis, striving for mathematical abstraction and purity of line. I discovered again the free run of ... a line, subordinate only to the internal law of rhythm, through the free run of the hand". Given his drawings' strong homoerotic undercurrents, some scholars believe he was in a passionate affair with Jorge Palomino y Cañedo, an intellectual who was his guide in Mexico, and with whom, according to the historian Joan Neuberger, he experienced, a "kind of freedom he had never before enjoyed; [an] intellectual, emotional, sexual, artistic freedom".

Art critic Tanner Tafelski argues that, "The drawings are part and parcel with Eisenstein's life and work [and] another expression of his dialectical thinking, in this case, of two people, or things, coming together dynamically". A small exhibition of Eisenstein's graphic work appeared at a New York gallery in 1932 and, following Stalin's death, and the period of cultural "thaw", his drawings was given a major exhibition in Moscow in 1957. That same year, his unpublished writing, notes, notebooks, and drawings, were acquired by the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts.

Pencil, colored pencil, ink on paper - Private collection

Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Nevsky focuses on the life of Prince Alexander, a 13th-century saint and icon of the Russian Orthodox Church, and his struggle for territorial sovereignty. It was a highly patriotic theme that carried greater resonance with the impending threat of invasion by Hitler's armies. Eisenstein did not have full artistic freedom in making this film, however. He was assigned to work with filmmaker Dmitri Vasilyev and novelist Pyotr Pavlenko, who were in effect his "minders". Eisenstein was already distained by Stalin for his "bourgeois formalism", but making Alexander Nevsky, which was much more in keeping with the official Social Realist style, restored him into Stalin's good graces. It may even have saved his life, as during the Great Terror, also called the Great Purge, which began in 1936, at least a million Soviets were executed or sent to prison camps. Many of the condemned were leading intellectuals, artists, writers, and poets, and a number of them were friends or colleagues of Eisenstein, including his mentor, the great theater director, Vsevolod Meyerhold.

Alexander Nevsky was Eisenstein's first sound film, and the score, written by famous Russian composer, Sergei Prokofiev, acted almost as a protagonist in the film. The two men seemed to share an intuitive understanding and also a profound interest in artistic innovation, as Prokofiev often composed from the rough cut of the film, and Eisenstein composed scenes in response to the score. Eisenstein called the collaboration "vertical montage" as he felt the emotional and physical movement of the image became perceptible by means of the music. The contemporary conductor Valery Gergiev said that Prokofiev's score was "the best ever composed for cinema".

The film's most iconic scene is the "Battle on Ice", which is based upon the historical Battle on the Ice where Prince Alexander defeated German forces in 1242. In the film, the battle ends as the Germans attempt to retreat and the ice breaks beneath them. Eisenstein's staging was inspired, not by any historical records, but rather by John Milton's famous 17th century poem Paradise Lost which depicts "the battle in heaven" between God's angels and Satan and his demonic host. Defeated, Satan and his minions fall into a "bottomless pit". The film was successful in Russia, so much so that in subsequent accounts of medieval history, the "Battle on the Ice" is described as having occurred in Eisenstein's imagining. Eisenstein, however, appears to have had reservations about the finished film (although he wisely kept any disappointment to himself). In his diary he reproached himself: "It is the first film in which I abandoned the Eisenstein touch ... You ought to be ashamed of yourself, dear Master of Art!".

Ivan the Terrible, Part I

This iconic film still depicts Ivan the Terrible, played by Nikolay Cherkasov, in profile, his hawk-like visage peering down upon a snaking procession of petitioners in a wilderness of snow. The film historian Jay Leyda was to compare this image to Utagawa Hiroshige's wood block of a fierce hawk swooping down upon a snow-covered landscape in One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58). Perhaps reflecting the continuing influence of Japanese art upon Eisenstein, the director uses an almost graphic simplicity and aerial perspective to evoke Ivan's predatory power and far-sighted domination of the people below and the landscape itself. Vassilieva writes that the image evinces how "Stylistically, the film is characterised by excess ... Elements that are not necessary for the articulation and progression of the story but which, on the contrary, destabilize and complicate narrative at every turn abound in the film. They include the rich ornamental interiors, the biblical frescoes, the religious symbolism, and more formal elements - the shadows, the contrast between light and dark, the juxtaposition of close-ups and long plane, the tense, tight framing and the contrapuntal use of sound".

The film was the first part of a planned trilogy. It covers Ivan's power struggle with the aristocratic Boyars, and, in Eisenstein's words, "the whole range of his activity and the struggle for the state of Muscovy". The film's subject was particularly dear to Stalin, who identified with the figure of Ivan, and commissioned the film in 1941. However, when the Germans invaded Russia, the production was postponed until 1943 when it was filmed, primarily in Kazakhstan. The film was shown to the Committee on Cinema Affairs in 1944 and drew criticism for not emphasizing the accomplishments of Ivan enough. Nevertheless, the film premiered in Moscow in 1945 to acclaim and won Eisenstein the Stalin Prize in 1946.

Even today there remains considerable uncertainty as to whether Eisenstein glorified or critiqued Ivan and, by extension, his modern incarnation, Stalin. Historian Joan Neuberger argues, for instance, that "Ivan the Terrible was not only a shrewd critique of Stalin and Stalinism, it also raised profound questions about the nature of power, violence, and tyranny in contemporary politics, and in the history of state power more broadly. Eisenstein's film used Ivan's story to examine the psychology of political ambition, the history of absolute power and recurrent cycles of violence. It explores the inner struggles of the people who achieved power as well as their rivals and victims". Ivan the Terrible, Part II, completed shortly before his death, was screened in 1946 by the Central Committee. It reported, "Sergei Eisenstein has revealed his ignorance in his portrayal of historical facts, by representing the progressive army of Ivan the Terrible's Oprichniki as a gang of degenerates akin to the American Ku-Klux-Klan; and Ivan the Terrible, a strong-willed man of character, as a man of weak will and character, not unlike Hamlet". Stalin called the film "a nightmare".

Biography of Sergei Eisenstein

Early Childhood and Education

Born in Riga, then a part of the Russian Empire, Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was the only child of Mikhail Osipovich Eisenstein, a successful architect and senior city engineer, and Yulia Ivanovna, descended from a St. Petersburg family of prosperous merchants. Unfortunately, his parents separated acrimoniously when their son was eleven. Eisenstein's rebellious nature owed more to Freud than it did to Marx. He said, "The reason why I came to support social protest had little to do with the real miseries of social injustice, or material privations, or the zigzags of the struggle for life, but directly and completely from what is surely the prototype of every social tyranny - the father's despotism in a family".

Speaking of his early school days, Eisenstein recalled, "I belonged to the 'Colonists,' the Russian civil-servant class, detested equally by the native Latvian population and by the descendants of the first German colonists who had enslaved them" (the Eisensteins were part of Riga's large German population). Despite these prejudices, young Eisenstein showed great personal motivation, finding time to read Russian, English, and French, draw cartoons, read detective novels, and perform in a children's theater troupe (which he had founded). In 1915, he moved to Petrograd to continue his studies at the Institute of Civil Engineering (his father's alma mater). He also made time to study Renaissance art and attended avant-garde theater productions. He was enormously impressed with Carlo Gozzi's commedia dell'arte masterpiece, Princess Turandott.

After the first (February) Revolution of 1917, Eisenstein served both in the volunteer militia, and in the Engineer Corp of the Russian Army. He also sold his first political cartoons, signed under the pseudonym, Sir Gay, to several magazines in Petrograd. Shortly after the second (October) Revolution, he volunteered for the Red Army, while his father joined the Whites (the sworn enemy) and subsequently emigrated for fear of his life. During this time Eisenstein attended a performance of Masquerade, a play produced by the radical theatrical director Vsevolod Meyerhold. Eisenstein said that the experience felt like "a thunderclap" and sealed his desire to pursue a career in the theatrical arts rather than in engineering.

Early Career

While serving in the Red Army, Eisenstein worked as an engineer constructing defenses, and as theatrical director overseeing entertainment for the troops. In 1920, having been promoted to a command post, he was sent to Minsk where he first encountered Kabuki, a classical form of Japanese theatre known for its highly stylized performances. He began studying Japanese and was intrigued by kanji, a Japanese writing system, based on symbols which represent words or ideas. By the end of 1920 Eisenstein had completed his service and taken up the post of assistant set and costume designer for the experimental First Workers' Theater of the Proletkult Theatre (The People's Theatre), in Moscow.

In 1920, Eisenstein also studied for a brief period (around three months) at the Moscow workshop of Lev Kuleshov. The "Kuleshov effect", as it became known, stemmed from the idea that cinema was an assemblage of fragments of still images. The Kuleshov effect took an image of the Russian matinee idol, Ivan Mozzukhin, and juxtaposed it with unconnected images such as a bowl of soup, a woman reclining on a couch, and a dead child in a coffin. Although the image of Mozzukhin's face was the same, the audience read his expression as conveying different emotions depending on which of the images it was matched with. Kuleshov conducted similar experiments with "creative geography" whereby he spliced together library shots from different locations (some from different parts of the world) that created the impression of a single location.

![Vsevolod Meyerhold. Eisenstein said of the theater director, “The God-like, incomparable Meyerhold [...] I was to worship him all my life”.](/images20/photo/photo_eisenstein_sergei_2.jpg)

In autumn 1921, Meyerhold was appointed head of the State Higher Theatre Workshops in Moscow. Eisenstein, who came to idolize Meyerhold, was one of his first students. Eisenstein first worked on a production of The Mexican, a play that depicted an anarchist rebellion. His innovative suggestion that a boxing ring should be moved into the audience, to maximize the effect of an actual fight, drew added public intrigue to the production. However, his first excursion into filmmaking occurred in 1923 while working on an interpretation of Aleksandr Ostrovsky's satirical play, Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man.

In their revision of the original play, which they (re)named simply, Wiseman, Eisenstein and playwright Sergei Tretyakov, transformed the original script into a commedia dell'arte inspired revue. Originating in Italy during the Renaissance, commedia dell'arte ("professional comedy") is a burlesque theatrical style featuring masked characters, such as Harlequin, Pantaloon, Punch and Pierrot. Wiseman incorporated Eisenstein's short, three scene, film, Glumov's Diary. The first scene showed Eisenstein taking off his hat and bowing in front of a poster announcing the play. The second revealed how Glumov's diary had been stolen and was notable for the way Eisenstein juxtaposed filmed imagery with live action (an actor runs onto the stage and vanishes, only to reappear on film scaling the side of a building). The third sequence, revealing the diary's contents, closed the theatrical performance. Eisenstein famously referred to the stage/film production as "a montage of attractions".

In 1923, Constructivist artists had organized themselves into a group called "Left Front of the Arts" under whose auspices they published the highly influential avant-garde journal, LEF (1923-25) (and later, New LEF, 1927-29). The journal defended the avant-garde against both the rise of Socialist Realism (as favored by Stalin who came to power in 1924) and the threat of a rebirth of a traditional bourgeois/capitalist art. For the contributors of LEF, the modern medium of cinema held the greatest potential for defense against these dual threats. ("Bourgeois" Hollywood cinema had already mastered a highly sophisticated system of montage based on continuity and transparency between shots. Eisenstein was pioneering a montage strategy that was its antitheses.) Other pioneers of the Soviet Formalist cinema included Vsevolod Pudovkin, Esther Shub, and Dziga Vertov.

Eisenstein published his theories in LEF. He argued that "cinematography is, first and foremost, montage" while his blueprint for a "montage of attractions" accounted for "any aggressive moment [that] subjects the audience to emotional or psychological influence, verified by experience and mathematically calculated to produce specific emotional shocks in the spectator". He would propose a total of five stages of dialectical montage - metric, rhythmic, tonal, over tonal, and intellectual - all designed to combine and combust in the creation of a revolutionary commercial cinema that, in the words of historian Julia Vassilieva, "linked to the project of the construction of socialism". Eisenstein's underlying premise was founded on the Marxist dialectic: shot A: thesis, placed next to shot B: antithesis, created something independent of both individual shots: synthesis. In other words, by putting together shots that had no logical connection he was awakening (or "agitating") his audience as they worked to make meaning of what they were witnessing.

Mature Period

Following Wiseman, Eisenstein was approached by the USSR State Committee for Cinematography (Goskino), and the Proletkult Theater. This led to a provisional agreement by both parties that he would direct a series of pro-Proletariat films featuring members of the Proletkult Theater. The team decided to begin with Strike (1924), a subject considered to have the greatest audience appeal. Film historian Julia Vassilieva writes of Strike that "Although the action was based upon the 1903 strikes at Rostov-on-Don, and the closing intertitle refers to a number of strikes that occurred in Russia between 1903 and 1915, the imagery was abstracted from any geographical or historical particularity". Similarly, his non-professional actors (those not drawn from the Proletkult Theater) were selected because they were representative of their "type", such as workers, worker's wives, foremen, and revolutionaries. In sharp contrast to these authentic and convincing representations, the villains of Strike were presented in the tradition of the commedia dell'arte. Capitalist bosses were, for instance, represented as bumbling caricatures, while the spies employed to sabotage the strike were given the names and characteristics, and were juxtaposed with images of animals.

With Strike, Eisenstein was more or less free to experiment with his radical montage techniques. For example, images of workers being beaten down by Tzarist troops on horseback were juxtaposed with horrifying images of live cattle being butchered in an abattoir (ergo, the workers could be likened to defenceless animals being slaughtered). On viewing the daily rushes, however, the Goskino committee became concerned that the film lacked a coherent narrative. It was only when members of the film crew backed the director that the project proceeded. While many critics praised the film, general audiences gave it a mixed reception. Eisenstein later describe Strike as "Awkward. Angular. Surprising. Bold. [And containing] the seeds of nearly all the elements that, in more mature form, appear in my works of later years. It is a typical 'first' work,' bristly and pugnacious, as was I in those years".

Almost immediately after Strike, Eisenstein began filming Battleship Potemkin. Released in 1925, it focused on historical events, this time a 1905 mutiny in the Russian Imperial Navy. Battleship Potemkin would feature, through its six minute Odessa Steps sequence, one of the most analyzed and influential examples of dynamic editing in the history of cinema. Eisenstein, who used all the montage techniques at his disposal to rouse his audience, showed Czarist troops systematically descending the monumental steps as they murdered and maimed members of the public who had come out in solidarity with the mutineers. (The impact of the sequence remains undeniable, but the massacre was in fact fictitious.)

Eisenstein had begun work a new project, The General Line (1929), a propaganda film that would depict a Russian village's transformation due to the revolution and agricultural collectivism, when Stalin commissioned him to make a film celebrating the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. For the production of October (1927), Eisenstein was given access to sites where historical events had taken place, as well as all the material resources he needed. The film is seen as the height of Eisenstein's radical montage techniques although the finished film divided critical opinion, with many accusing Eisenstein of being over-indulgent and paying little heed to historical accuracy.

Eisenstein had planned his next film, Capital, focused on Marx's political work Das Kapital (1867-94), as something akin to novelist James Joyce's "stream of consciousnesses" writing technique. Capital was never filmed. Instead, he returned to The General Line project. It was Eisenstein's first film to depict a contemporary fictitious subject, and used individual protagonists (rather than the masses) to carry the plot. It debuted in 1929 under the title, The Old and the New. The British Film Institute (BFI) describes the film as "A beautiful and hypnotic spin on familiar Soviet 'labour' films, it's a document of agricultural policies filled with undercurrents of homoeroticism and sadomasochism, and perhaps most famous for the dizzying sexual overtones of its cream-separator sequence". Sadly the (silent) film was generally overlooked, due in no small part to the birth of the era of sound cinema.

Late Period

In 1929 Eisenstein, with Grigori Aleksandrov and Eduard Tisse, travelled to Western Europe to represent the Soviet arts and to learn about new sound technologies. The trio toured the major European cities - Berlin, London, Zurich, and Paris - where the director was much in demand with leading intellectuals, artists, scientists, film stars, and producers. He participated in the 1929 Congress of Independent Filmmakers in Switzerland, and also, while in that country, directed a public health film about the importance of legalizing abortion, titled Frauennot – Frauenglück (Women’s Hardship – Women’s Happiness).

In 1930 Paramount Studios invited Eisenstein and his entourage to Hollywood. He explored several projects with the studio, although differences between both parties became quickly apparent. Eisenstein proposed a film, Black Majesty, telling the story of Henri Christophe, a slave who led the Haitian revolution. The project was dismissed by Paramount as too controversial for a country still living under the cloud of racial segregation. Paramount then proposed a film based on An American Tragedy, the noted novel (based on real events) about crime and punishment, by Theodore Dreiser. However, Eisenstein's outline was seen as too dark and his contract with the studio was duly cancelled. During his Hollywood sojourn, however, Eisenstein met Charlie Chaplin and Walt Disney. He felt a particular connection with Disney and greatly admired the sinuous and animated lines of Disney's anthropomorphic animal figures.

In light of the cancellation of his contract with Paramount, Eisenstein was expected to return to Soviet Union. He was reluctant to do so, fearing he would be seen as a failure at a time when his work was coming under increasing attack for its excessive formalism. Chaplin had introduced Eisenstein to the novelist and socialist, Upton Sinclair, and his wife Mary. Along with several other financial backers, the Sinclairs formed the "Mexican Film Trust". In late November 1930, Eisenstein signed a contract with the Trust to make an hour-long, non-political film, to be completed within four months.

Eisenstein arrived in Mexico City in early December and immediately began filming Que Viva México! (Long Live Mexico!). As film historian Gabrielle Murray describes, "what he began to explore was nothing less than the intermingling of past and present, the nature of things, changing and eternal, and the meaning of death. This was an enormous task, but one that would allow him to pose questions about religion, sexuality and communal experience - existential questions not easily answered by Soviet solutions". Eisenstein, who was blissfully engaged in an affair with his guide, Jorge Palomino y Cañedo, described the country as a "lost and newly-regained paradise". His stay in the country also revived his dormant interest in drawing, with his numerous sketches focused on the human body, the homoerotic, and a fluidity of being.

Eisenstein did not get to finish Que Viva Mexico!. The film historian Chris Robé puts this down to, "political and aesthetic disagreements with Upton Sinclair ... over the film's composition; the difficulty of gaining mass distribution for the film", and Stalin's insistence that Eisenstein "stop filming and immediately return home before being deemed a deserter to the Soviet Republic". Before leaving Mexico, Eisenstein sent some suitcases to the United States, but they were seized at the border as they contained many of his explicit drawings of male lovers and photographs of male nudes.

When he did arrive back in the Moscow in 1932, Eisenstein was viewed as having failed in Hollywood and in Mexico. He had expected to take ownership of the footage he had shot in Mexico, but was despairing at the news that the Sinclairs retained ownership of the film stock and had allowed the footage to be made into a number of short films. Eisenstein also had to contend with the Soviet state's criminalization of homosexuality. He suffered a nervous breakdown which led to a spell of several months in a psychiatric hospital.

In 1934 Aleksandrov directed and acted in a film called Jolly Fellows. The film marked the end of the two men's friendship, possibly because Aleksandrov became romantically involved with his co-star, the actress Lyubov Orlova, who was loved by the Soviet people (Stalin included). Film critic Vitaly Vulf notes that Eisenstein's friendship with Aleksandrov "is still a subject of speculation and gossips, although there is no evidence they had had a sexual relationship. Aleksandrov himself took these rumors calmly: 'Maybe he was infatuated by me ... I've never been infatuated by him.' Eisenstein, for the rest of his life, believed Aleksandrov had betrayed him when he married Orlova". A few months later, Eisenstein married Pera Attasheva, a journalist and actress, though in his memoirs he said they never kissed, lived apart, and that their marriage was strictly platonic.

Late Period and Death

Without commissions or interest in his films, Eisenstein continued working on his theoretical magnus opus, Method, which he had begun writing in Mexico. As Vassilieva described, Method was "dedicated to formulating a unified method of art ... At the core of his theorizing ... Eisenstein positioned what he called the Grundproblem, the German term he used to define the central problem of art, which he saw as the paradoxical coexistence of two dimensions or axes in any work of art: the logical and sensuous, cognitive and emotional, rational and irrational, conscious and unconscious".

At this same time, the political climate in Russia was becoming increasingly repressive. The Soviet Writer's Congress in 1934 established the principles of Socialist Realism, favoring simple narratives with an inspiring hero. Movies like Chapaev (1934), directed by the Vasilyev brothers and telling the story of a peasant who became a commander in the Red Army, were not only celebrated but mandated. Directors were seen as secondary to scriptwriters, as the emphasis was on compelling scripts embodying the aspirations of the common people and the orthodoxy of the party. Eisenstein presented his concepts from Method in 1935 at the All-Union Creative Congress but they were roundly dismissed as being incompatible with the goals of Soviet Socialist Realism.

After the collapse of a proposed project for a group called the Communist Young Pioneers, Eisenstein was assigned, Alexander Nevsky (1938), the story of a medieval Russian prince who defeated an invasion of Teutonic Knights of the Holy Roman Empire in the famous Battle on the Ice. Emphasizing a Russian hero who defeated a German invasion, the subject greatly appealed to Stalin who also viewed himself as his nation's savior. It was Eisenstein's first sound film, and he worked closely with the eminent composer, Sergei Prokofiev, who wrote the film score. The overall effect was masterful. The film was a popular and critical success, and Eisenstein's reversal of fortune was confirmed when he was awarded the Lenin Prize and the Stalin Prize.

Debate continues among critics whether Eisenstein's later works were masterworks or deformed by propaganda. He himself said that Alexander Nevsky had very "little Eisenstein" in it. Nevertheless, he remained committed to the Soviet/socialist cause, stating after the film's release: "my subject is patriotism". Subsequently, Stalin commissioned the director to produce a trilogy of films on Ivan the Terrible, a brutal tyrant in the mold of Stalin himself. Stalin commissioned Ivan the Terrible, Part I, in 1941. When the finished film was viewed by the Central Committee in 1944, it was criticized extensively. However, it debuted in Moscow in 1945 to great public acclaim.

Suffering with increasingly poor health (and having recently been struck down by a near-fatal heart attack) Eisenstein worked at pace on Ivan the Terrible, Part II. When it was screened for the Central Committee in 1946, its official verdict was unequivocal: "Sergei Eisenstein has revealed his ignorance in his portrayal of historical facts, by representing the progressive army of Ivan the Terrible's Oprichniki as a gang of degenerates akin to the American Ku-Klux-Klan; and Ivan the Terrible, a strong-willed man of character, as a man of weak will and character, not unlike Hamlet". Stalin called the film "a nightmare" and the film was banned.

Eisenstein continued to take instruction from Stalin, who suggested that the director could remake the film and emphasize Ivan's character as a ruthless strongman and dynamic leader. Eisenstein had lost faith in the project, however, and made no effort to undertake the edits. He died in February 1948 while writing a letter. Recognizing what was taking his last breaths, he wrote, "At this moment I am having a heart attack. Here, the trace in my handwriting". Following his death, his brain was donated to scientific research, and his body was laid out in the House of Film before being buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery.

The Legacy of Sergei Eisenstein

Eisenstein showed how the medium of cinema could be mobilized in the causes of revolutionary propaganda to striking effect. Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October are permanent reminders of the creative muscle and dynamism of agit-prop. But, as Julia Vassilieva noted, since the beginning of the 21st century, "our understanding of Eisenstein's legacy has been reshaped". In 2004, for example, the eminent English synth-pop duo, Pet Shop Boys, wrote a new score for Battleship Potemkin. Joining forces with Dresdner Sinfoniker, an orchestra featuring traditional musicians from Turkey and Armenia, they performed the score for an outdoor screening of the film in London's Trafalgar Square to an estimated audience of 25,000. In 2025, the BFI marked the film's 100th anniversary when it exhibited Battleship Potemkin (in lieu of a nationwide tour) with a recording of the Pet Shop Boys/Dresdner Sinfoniker score. Lead Programmer, Kimberley Sheehan said of the screening, "It is always a gift to witness one of the greatest silent epics on the big screen, but [the new] soundtrack blends electronic beats with orchestral grandeur, offering a stirring contemporary twist on the classic masterpiece".

Through his jolting cutting techniques, his juxtaposition of images (to create metaphor), or his rhythmic and metric use of close-ups and long shots to create a feeling of chaotic disorder - oftentimes to underline socio-political and/or psychological themes - Eisenstein has informed future generations of experimental and commercial filmmakers. He is an acknowledged influence on French Nouvelle Vague pioneers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais, and on the American experimental filmmaker, Stan Brakhage. While a little less pronounced, his influence can also be traced in Hollywood, most notably, perhaps, in Alfred Hitchcock's infamous shower scene in Psycho (52 cuts in a 45 second sequence) (1960), and Brian De Palma's unabashed homage to the Odessa Steps sequence in The Untouchables (1987). The British figurative artist, Francis Bacon, meanwhile, spoke openly about his admiration of the same sequence and cites the harrowing close shot of a screaming nurse - with her shattered pince-nez - as the inspiration for signature works such as Fragment of a Crucifixion (1950), and Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953).

Eisenstein's ability to manipulate emotions through the use of music and image, is credited, too, as a major inspiration on the MTV music video makers who adopted en-masse his dynamic "montage of attractions" techniques in order to capture the attention and imagination of their audience. Vassilieva concludes, "No doubt, Eisenstein was one of the creative and intellectual giants of the twentieth century, a polymath comparable to the Renaissance figures such as Leonardo or Michelangelo - a comparison he himself welcomed. His vast heritage is still being mapped, explored, [and] appropriated".

Influences and Connections

-

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo ![James Joyce]() James Joyce

James Joyce- Carlo Gozzi

- Lev Kuleshov

- Vsevolod Meyerhold

- Sergei Tretyakov

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Eduard Tisse

- Charlie Chaplin

- Walt Disney

-

![Francis Bacon]() Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon ![Alfred Hitchcock]() Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock- Jean-Luc Godard

- Alain Resnais

- Stan Brakhage

- Sergei Tretyakov

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Eduard Tisse

- Charlie Chaplin

- Walt Disney

-

![Constructivism]() Constructivism

Constructivism - Nouvelle Vague

- American Experimental Film

- New Hollywood Cinema

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI