Summary of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

Few artists in history have painted inanimate objects with such intricacy or luminosity so as to incite emotional reactions. With a less than straightforward trajectory to fame and success, and his name all but forgotten by the time of his death, Chardin's later rediscovery cemented his reputation as one of the most celebrated of all still life painters. At the time he was working, still life painting was one of the least-acclaimed disciplines: genre and history painting were seen as the ultimate demonstration of artistic ability and anything else was frequently dismissed as merely 'craft'. Persisting in his modern, realist style throughout his career, Chardin's subversive attitude has since awarded him the status of an icon for many modern and contemporary artists.

Accomplishments

- Throughout his life Chardin suffered a great deal of personal loss, and this often permeates his paintings in the use of known visual tropes such as blown bubbles and precariously balanced objects, as with knives hanging on the edges of tables. His juxtaposition of such sombre themes with scenes from everyday life is what separates Chardin from other painters of the time.

- Because of their often visceral detail, especially in illustrating dead fish and flayed animals, Chardin's paintings were revisited by modern artists especially in the age of Surrealism, with some considering Chardin as a Proto-Surrealist painter. Chardin's work demonstrated a love of beauty in previously unacknowledged places, to the extent that his objects would take on a magical quality previously unforeseen in the history of painting.

- Chardin's genre paintings share a lot of similarities with his still lifes. Unlike his contemporaries who were consumed with the allegorical and figurative aspects typical of Rococo painting, Chardin gave as much attention to the objects in his paintings as he did the people. More typically in portraiture, objects appear only as 'accessories' to the person portrayed. But pictured in moments of quiet reflection, Chardin’s sitters often seem to be the accessories themselves.

Important Art by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

The Ray

Considered by many as his first masterpiece, The Ray, presented together with a later work, The Buffet (1728), earned Chardin his place at the Académie. As a bold declaration of both his abilities as an artist and of the expressive capacities of still life painting for which Chardin came to be renowned, this painting was intended to dazzle and shock. At the work's centre, a gutted ray (also known as a skate) hangs suspended, its wound and translucent flesh revealing its inner anatomy. The critic Denis Diderot was struck by the realistic way in which Chardin paints the ray, writing, "It is the fish's very flesh, its skin, its blood!," describing how its "terrifying face" bears an uncanny resemblance to a human expression. The gaunt lifelessness of the fish's form is thrown into sharp relief by the juxtaposition of the small cat to the left, its back arched and fur prickling as it steps lightly upon scattered oyster shells.

Marcel Proust would later take notice of The Ray's haunting beauty, praising the painter's ability to take a "strange monster" and turn it into "the nave of a polychrome cathedral." This sculptural, even architectural property of Chardin's masterpiece is accentuated by the stark contrast between the left and right sides of the picture plane. The assembled subjects, both alive and deceased, all congregate on the left, as if representing an interior, much like Proust's 'nave'. The assortment of kitchen utensils on the right is more like an exterior. Here Chardin demonstrates his skill at depicting light reflections, while the cooking objects remind us of the work's context and the intended fate of the fish. Smooth and highly polished, these inanimate objects provide a three-dimensional sense of completeness to the work against the flatness of the ray and even of the foreshortened cat, while the bunched table linen, half-suspended knife and upended bucket unify and preserve Chardin's message of fragility and precariousness.

Exemplary of his early experiments in still life, The Ray has remained one of his most admired works. It has been copied by modern masters such as Henri Matisse, who translates the scene into quasi-abstract geometric planes, and Chaïm Soutine, whose deep interest in somewhat bloody still lifes of game has a sustained dialogue with his eighteenth-century predecessor.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Washerwoman

Scenes such as The Washerwoman are exemplary of Chardin's later turn towards domestic genre painting. After his admission to the Académie, Chardin began to expand his repertoire to include the human figure, which was at the time still considered to be an essential skill for successful painters. Genre scenes such as this were also more profitable than still lifes, as they were more highly valued due to their perceived difficulty and sophistication, but also because of the recent surge in popularity of seventeenth-century Dutch genre paintings.

Looking off to the side in a moment of mild distraction, a woman's ruddy cheeks catch the light, her hands submerged in a basin full of linens. A young boy sits on a low stool beside her, solemnly blowing a bubble, a classic vanitas image that speaks to the fragility of life. Though his domestic perspective, as was inherent to Chardin's style and to the success of works such as The Ray (1725-26), has here widened to incorporate human subjects and their daily activities, Chardin's Washerwoman retains his striking attention to light and surfaces where his canvas reads as an encyclopedia of textures: the gleam of the boy's bubble, the calico fur of the cat, the straw-strewn floor, the cascade of fabric of the woman's apron and bonnet. The painter imbues his humble subject with a visual richness that lends the scene a sense of dignity. What is more, the woman's work of scrubbing the linens clean, with the ritual completed by a second woman in the background tending to a washing line, suggests that Chardin was keen to convey a sense of propriety in these domestic scenes. Rather than a single figure tending to her chores in solitude, Chardin paints a production line, which brings with it a sense of community and shared respect for their everyday, essential task. The influence of Dutch genre paintings on Chardin is also made evident through his compositional strategy, as he makes use of the Dutch technique of the doorkijkje - the view through the doorway - in order to expand his representational space and include another figure. The use of such a device further speaks to Chardin's eagerness to demonstrate his talents at this pivotal point in his career.

Oil on canvas - Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Soap Bubbles

As with his paintings of everyday kitchen tools or domestic figures, in his Soap Bubbles, Chardin lends subjects that might otherwise be dismissed as trivial a sense of dignity. A young boy leans on a windowsill, his face fixed in concentration as he blows a bubble at the end of a straw. His companion, fingers gripping the edge of the sill, looks on in rapt fascination.

There has been much debate among scholars concerning whether or not Chardin intended his image to have an allegorical meaning about the fragility of life. Certainly, soap bubbles were understood at the time to act as symbols of ephemerality, though whether Chardin had this in mind remains unclear. Less questionable, however, is the striking naturalism with which he represents his figures and their surroundings, from the play of light and shadow on his subjects' faces, to the replay of greens in the reflection on the central bubble, presumably from the nearby foliage.

As Chardin developed his talents as a genre painter, he began to incorporate figures from the middle and upper classes, perhaps to appeal to a wider audience. Children's play was a subject of particular interest to him, and he would often feature children in his work, playing with their spinning tops, card games, reading, and here blowing bubbles. But even scenes of leisure like this are orchestrated with Chardin's typical sobriety: the composition is laid out in a series of strong, pyramidal configurations, and his use of mostly earth tones lends the canvas a sense of groundedness. The confluence of the boys' gazes on the bubble betrays utter concentration and seriousness about their task; the younger of the two studying the actions of the elder, as if hoping to emulate him.

Édouard Manet would go on to see another version of this painting at its sale in Paris in 1867, inspiring him to paint his own Soap Bubbles in the very same year. That Manet was fascinated by Chardin's expert rendering of the collision between light and surface speaks to the latter's resounding influence on modern painting well beyond his time.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The House of Cards

Painted at the height of his popularity and the apex of his genre painting phase, The House of Cards exemplifies Chardin's ability to depict in great detail a subject of composure and refinement whilst still delighting in more playful topics like card-playing. A young boy in a frock coat sits at a felted table, his elbows and shoulders set as he steadily adds a playing card to the first tier of his card pyramid.

The model for this painting, which was exhibited at the Salon of 1741, was the son of Jean-Jacques Le Noir, a successful furniture dealer and close friend of the artist. The House of Cards is just one of a number of works commissioned by Le Noir throughout the 1730s and 1740s, and is indicative of Chardin's increased success and popularity among the French elite. Chardin painted a number of young subjects building houses of cards, which, in their temporary, looming beauty, are often associated with the fragility and unpredictable instability of life. Indeed, when the painting was engraved by François-Bernard Lépicié in 1743, it was accompanied by a caption that read: "Dear child all on pleasure bent / We hold your fragile work in jest / But think on't, which will be more sound / Our adult plans or castles by you built?" At once playful and melancholic, this verse demonstrates the pliability of Chardin's paintings, as they can be interpreted as moralizing, yet also simply as meditations on the beauty of forms and surfaces. The careful attention to the folds of the tricorn hat, the subtle suggestion of depth by way of the open drawer, and the painting's harmonious, creamy tones reveal both Chardin's meticulous observation and the affection with which he treats his subject. The boy, fixated on his task, seems to echo the utter concentration and steady hand with which the painter himself would have worked on his canvas. The almost-secret smile that plays across the boy's face betrays the pleasure both of play and of painting, suggesting a touch of irony (or at least lightheartedness) in the face of the work's potentially somber allegory.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

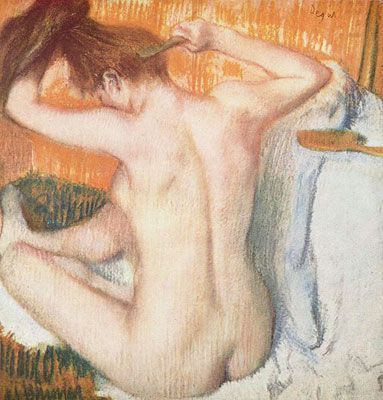

Basket of Wild Strawberries

After a long hiatus from still life painting, Chardin sought refuge in it again toward the end of his life after a series of personal tragedies. Basket of Wild Strawberries is exemplary of this late still life period: the painter remains dedicated to the simplicity of everyday, household objects, but now approaches them with a more sophisticated eye for geometric composition.

A brilliant soft pyramid of strawberries glistens at the center of the canvas, catching the light, deep reds and flecks of green in sparkling contrast to the muted browns in the background. The bright white of a pair of carnations throw the red of the strawberries into even starker relief, these bursts of color energizing the painting. At first glance, the objects in Chardin's late still lifes might appear haphazardly arranged, yet here, the horizontal of the counter is strengthened by a second, parallel plane formed by the water within the glass, the edge of the wicker basket, and the small group of fruit to the right. The carnations, placed just slightly off-centre, create a disruption visually and physically too, in their intentionally precarious position on the edge of the table. The triangle of the strawberries also finds its geometry redoubled, as it sits at the apex of a bigger pyramid formed with the glass and the peach.

After fifty years of practice, Chardin has mastered the genre of still life so completely that he is free to play with the formal elements. That the water glistening in its glass and the velvety petals peeling off of the flowers are rendered with astonishing naturalism further demonstrates his expertise. As Edmond and Jules de Goncourt would come to write about Chardin in the 1860s, "He raised this secondary genre to the highest and most marvelous condition of art. Never had the enhancements of material painting, which touches upon the most commonplace objects to transfigure them by the magic of rendering, been brought further."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Self-Portrait with Spectacles

One of a number of self-portraits made by Chardin late in his life, here the artist appears in three quarter view, turning towards us with penetrating brown eyes, his head slightly bent as if to fix upon his viewers with his gaze. In both an honest representation of his appearance and as a symbol of his trade, Chardin sports an intricately entwined blue and white cap, along with a colorful, geometric-patterned scarf that catches the light in a way so as to appear as silk, along with spectacles delicately perched upon the bridge of his nose. The glasses also bring our attention to a significant change in medium: in the early 1770s, Chardin's eyesight began to fail, and fumes from the lead-based oil paints with which he had always worked exacerbated his condition. Rather than give up his career, he turned to pastels, which brought him as best possible to the full range of colors and textures of paint. The appearance of this pastel work (along with a number of others) at the Salon of 1771 shocked his viewers, though he was still praised by Denis Diderot for "the same confident hand and the same eyes accustomed to seeing nature - seeing nature clearly, and unraveling the magic of its effects." Though Chardin had merely dabbled in portraiture throughout his career, his late pastel portraits are strikingly intimate, and communicate the psychological depth of their sitter. This self-portraits is no exception, as his wry smile appears knowing and shrewd, the juxtaposition of tones on his face making him seem sculptural and almost life-like.

Chardin fell out of favor with the art world in the last decade of his life, and it would not be until the next century that he was to take his place in the French artistic pantheon. This self-portrait in particular gained a reputation when it was seen by a young Marcel Proust, who wrote passionately about it in 1895, "Go to the Pastel Gallery and see the self-portraits Chardin painted in his seventieth year. Above the outsized pair of glasses that have slipped to the end of his nose and are pinching it between two brand new lenses, are his tired eyes with their dulled pupils; the eyes look as if they have seen a lot, laughed a lot, loved a lot, and are saying in tender, boastful fashion: 'Yes, I am old!' Behind the glimmer of sweetness dulled by age they still sparkle."

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

Biography of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

Childhood and Education

Not much is known about the early years of the life of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. Born on the Rue de Seine in Paris, Chardin spent his childhood accompanying his father, a maker of billiard tables, at his workshop. Successful but humble, Chardin's family was part of a class of bourgeois artisans, which would come to influence the subjects of many of his later genre paintings. The young Chardin first joined the studio of the painter Pierre-Jacques Cazes, where he learned the techniques of academic drawing, and then that of Noël-Nicolas Coypel, a celebrated history painter. Though Chardin would go on to have little interest in history painting, an assignment from Coypel, of copying a musket from life for inclusion in one of the master's hunting paintings, led him to the style of meticulous observation with which his name would become synonymous. He received further training at the Académie de Saint-Luc, a guild akin to that of the Guild of St Luke, the patron saint of painters. Chardin's work in these early years included a number of genre scenes, as well as a signboard commissioned for a Parisian surgeon's office.

It was his still life scenes, however, which garnered the attention of the Académie Royale de Peinture. By September of that year, he had been received by the Académie as a painter "of animals and fruit." Selecting seemingly mundane objects such as kitchen utensils, vegetables, copper pots, eggs, and other household items, Chardin reveled in the various textures and simple forms of his subjects. By 1731, Chardin was earning enough of an income to marry Marguerite Saintard, to whom he had been engaged since 1723, never having sufficiently secure finances to allow for the union. Soon after, he received his first official commission for the Parisian home of Conrad-Alexandre de Rothenbourg, the French ambassador to Spain, for which he produced a pair of decorative panels entitled Attributes of the Arts and Attributes of the Sciences (1731).

Mature Period

Though Chardin's newfound position as an Academician brought him more respect and artistic freedom, the 1730s were not peaceful years for the painter's personal life; in 1735, his wife died, followed by the death of their daughter only a year later. Suffering this considerable distress, Chardin himself struggled with illness into the early 1740s. Such personal difficulties, however, did not stand in the way of the artist continuing to cultivate his career and repertoire. Perhaps driven by financial considerations - still lifes had a fairly modest price - as well as a rise in popularity of seventeenth-century Dutch paintings, Chardin began to develop his skills as a genre painter, though still with a notable taste for domestic interiors. The human figure had long since been the mark of standard for Academicians attempting to make a name for themselves, and so it is no surprise that Chardin took to genre scenes as a way to increase both his income and his prestige. The re-establishment of the Salon in 1737 offered Chardin further motivation for developing his oeuvre beyond still life. A number of these scenes were engraved by Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1688-1779), who is cited as one of Chardin's few close friends. That one of Chardin's closest acquaintances was with his engraver highlights just how small his social circle was, and how serious a manner in which he worked. Although Chardin lived in Paris and rarely left, his self-contained attitude to painting often led to his being mistaken for a rural painter.

Chardin remarried in 1744, this time to Françoise-Marguerite Pouget, with whom he had a daughter who did not survive past infancy. Perhaps the struggle of losing yet another child led him to return to painting still lifes in the late 1740s, though very little record of his personal life and experience survives from this period. Though he would stop producing new figural genre scenes after 1750, he continued to reproduce his own works and motifs with slight variations, suggesting their popularity and salability in European art markets. His second period of still lifes saw a return to the kitchen and pantry scenes of his early career, though with a markedly increased variety of objects and configurations. It is probable that his increased financial standing allowed him access to finer household wares, as indicated by the inclusion of glassware, fine silver, and porcelain vessels in these later works.

Chardin's focus shifted from the minute details of each object to the overall effects of their composition as an ensemble, as can be seen in works such as The Butler's Table (1763) and The Basket of Wild Strawberries (1761). However, his lifelong penchant for representing the effects of light and shadow bridges both his early and late periods of still life practice. Despite the fact that, overall, commissions for still life paintings were few and far between, Chardin's reputation had garnered him considerable favor, and he received a number of commissions for overdoors in the 1760s, such as those still found in the Château de Choisy and the Château de Bellevue. In 1766, Catherine the Great commissioned an overdoor for the lecture hall at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts, for which he produced The Attributes of the Arts and Their Rewards (1766). These decorative panels demonstrate his ability to elevate the officially lesser genre of still life to new heights, as he instills his allegorical subjects with a sense of dazzling monumentality and significance. The renowned art historian Pierre Rosenberg wrote of them, "Never was decoration less decorative."

Late Period

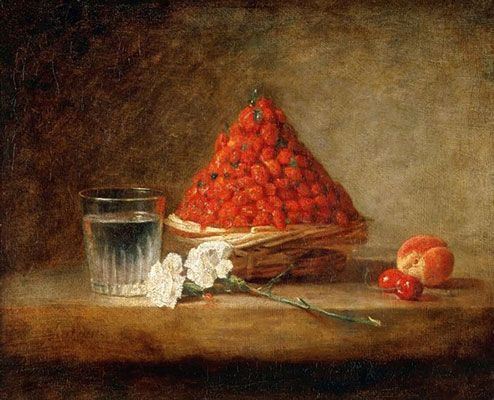

Chardin's submission to the Salon of 1771 shocked his peers and public alike; in the place of his usual still lifes or genre paintings, he exhibited three pastels, including his Self-Portrait with Spectacles (1771). There had already been rumors spreading around Paris that he had fallen ill, but it was not until the early 1770s that it was discovered that the great painter's eyesight was failing him. He wrote in a letter to Comte d'Angiviller, "My infirmities have prevented me from continuing to paint in oils, and I have resorted to pastels." The lead-based oil paints used by eighteenth-century artists emitted fumes that aggravated Chardin's already weakened eyes. Pastels, on the other hand, had no such adverse effects, and thus allowed him to continue to work. Coincidentally, this same condition, amaurosis, a paralysis of the eyes, would strike Edgar Degas a century later; he too would turn to pastels as a solution. Chardin's pastel portraits are characterized by bold color and a painterly touch, as he experimented with the textures that different papers allowed him. Though he had made very few portraits throughout his career, these late works demonstrate Chardin's talent both for life drawing and for rendering subtle modulations of light and tone.

The last decade of his life proved difficult for Chardin. Tragedy struck his personal life yet again in 1772 when his only surviving child, Jean-Pierre, who had followed in his father's footsteps and begun a career as a history painter, drowned in Venice. Moreover, a change in leadership at the Académie put the painter out of favor, and soon, out of popularity. The emergence of Neoclassicism as the official style of painting at the end of the eighteenth century meant that Chardin's work was associated with the frivolity and indulgence of Rococo painting, despite his lifelong taste for humble subjects, simplistically represented. By the time Chardin died in 1779, his name had been virtually forgotten by the Parisian art world.

The Legacy of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

Though he ended his life and career in near obscurity, Chardin was highly influential for a number of important artists in the generation that followed him, including Jean-Honoré Fragonard, who studied with him before going on to work with François Boucher, and Jacques Louis David, whose efforts in the Académie Chardin had supported, despite their stylistic differences. He later received his due honors in the mid-nineteenth century when he was "rediscovered" by Realist critics such as Théophile Thoré and Jules Champfleury, the latter being the great champion of Gustave Courbet. A series of articles on Chardin published by the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt in the early 1860s introduced him to the painters with whom the birth of modernism is associated, most significantly, Édouard Manet, whose own still life paintings betray the influence of Chardin's subtle depictions of light, as well as his lifelong celebration of the dignity in everyday subjects. Paul Cézanne would go on to praise Chardin's pastels, and Henri Matisse once called him his favorite painter. This later return to popularity among painters and critics led to the Louvre moving swiftly to acquire his work, firmly reinstating his illustrious position in the history of French painting. Freed from the aristocratic associations of the Rococo, Chardin stands as a singular painter in the history of eighteenth-century art, as his taste for simply composed, humble subjects allowed his talents to shine through in both oil and pastel.

Influences and Connections

-

![Jean-Antoine Watteau]() Jean-Antoine Watteau

Jean-Antoine Watteau - Gabriel Metsu

- Jean-Baptiste Oudry

- François Desportes

- Charles-Nicolas Cochin

-

![Dutch Golden Age]() Dutch Golden Age

Dutch Golden Age - Academic Art

- Denis Diderot

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI