Summary of Glass Art

Glass art is a uniquely hybrid field within the visual arts, positioned at the intersection of science, craft, industry, and fine art. Emerging independently across ancient civilizations including Egypt, Mesopotamia, Rome, and China, glass was initially a rare, technically demanding, and resource-intensive material, closely associated with power, ritual, and prestige. Over centuries, innovations such as glassblowing, enameling, mosaic techniques, and stained glass expanded its expressive and architectural potential, allowing glass to function not only as ornament or luxury object, but as a medium capable of shaping space, light, and narrative.

The modern redefinition of glass as a fine art medium occurred in the twentieth century, particularly with the emergence of the Studio Glass Movement in the early 1960s. By transferring glassmaking from industrial factories into individual artists' studios, practitioners asserted authorship, experimentation, and sculptural intent. This shift liberated glass from purely functional or decorative roles and positioned it within contemporary art discourse alongside sculpture, installation, and conceptual practice.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Glass art presents the transformation of light into an active medium. It introduced the ability to shape and direct illumination itself, allowing artists to choreograph color, luminosity, and spatial experience. Through architectural and object-based works, glass altered how viewers perceive narrative, environment, and atmosphere.

- Glassmaking has long required an intimate understanding of chemistry, heat, and material behavior thus infusing the integration of scientific knowledge into artistic practice. Its history reflects a sustained dialogue between empirical research and creative experimentation, positioning glass as a medium where technical inquiry and artistic intent are inseparable.

- The rise of artist-controlled studios in the twentieth century shifted glassmaking away from anonymous production and toward individual vision. This transition reshaped perceptions of authorship, process, and originality within materials-based art.

- As glass art circulated across regions and empires, it absorbed and transformed local aesthetics, iconography, and techniques. Its adaptability made it a conduit through which ideas moved between civilizations, producing distinct yet interconnected artistic traditions, acting as a catalyst for cultural transmission and exchange.

- In recent decades, artists have embraced glass as a medium capable of addressing complexities such as fragility and strength, permanence and impermanence, control and chance. Its material and optical qualities have enabled new forms of expression that continue to push the boundaries of scale, meaning, and artistic discipline.

Artworks and Artists of Glass Art

Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun

When the burial chamber of King Tutankhamen was discovered in 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter, a wealth of artifacts was enclosed inside, many of which featured glass art that has been able to tell us much about glassmaking in Ancient Egypt. Much of the glass in Tutankhamen's tomb appeared as colored inlays on jewelry, weapons, chariots, and furniture, as well as countless glass beads, two headrests made entirely of glass, and glass amulets. In fact, as arts writer Megan McGovern explains, "Tut's tomb was discovered with the help of a blue faience [glass] cup. [...] An American businessman, Theodore Davis, found a blue faience cup with Tutankhamun's name on it, along with some other items, in a pit in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt, in 1907. Archaeologists had not yet found Tutankhamun's tomb, although they had searched for it. Davis dismissed the find's significance, but Egyptologist Howard Carter believed the cup was a sign that Tut's tomb might be in the Valley of the Kings, too. He was right."

Glass inlay is also found in the Pharaoh's famous Funerary Mask (or Death Mask), one of the most exemplary artifacts of Ancient Egyptian culture. The mask presents Tutankhamen in the likeness of the god Osiris, measures over twenty-one inches in height, and weighs about twenty-two kilograms. The majority of the mask is made of cold-worked copper-alloyed twenty-three karat gold, covered on the surface with a very thin layer of two different gold alloys: a lighter 18.4 karat shade for the face and neck, and 22.5 karat gold for the rest of the mask. It is inlaid with gemstones like lapis lazuli, quartz, obsidian, carnelian, ammonite, and turquoise, as well as faience, the porous glass invented by the Ancient Egyptians, which has a similar appearance to glazed ceramics. The glass appears in the pharaoh's beard, collar, and beaded necklace. Even the mask's distinctive blue stripes, according to glass research scientist Emeritus Robert Brill, are in fact glass inlay, and not lapis lazuli, as previously believed.

Indeed, the Egyptians often used glass to mimic precious stones, perhaps when those stones were scarce, or perhaps as glass could achieve even more brilliant colors than the stones themselves. Indeed, while today glass is commonly seen as a cheap imitation of more precious stones, for the Egyptians glass itself was a material reserved for royalty. As curator and critic William Warmus writes, "It was considered an elite substance and signifier of status, comparable to gold or silver, and it is probable that the material's rarity contributed to its prestige," and, as the prevalent use of glass inlay at sites like Tutankhamen's tomb indicates, "Glass was also recognized as an ideal ensemble player that sculptors could use to create complex multi-media works of art."

Gold, glass, and precious stones - Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Mosque Lamp of Amir Qawsun

Glassmaking flourished in the prosperous Islamic world between the seventh and fourteenth centuries, in part because Muhammad, founder of Islam, disapproved of the use of tableware and drinking vessels made from precious metals, so glass was an ideal substitute. Egypt was an important center for Islamic glass art during the "Golden Age" of Islamic glassmaking in the late twelfth to late fourteenth centuries. A notable example is the Mosque Lamp of Amir Qawsun, a large lamp typical of those commissioned by sultans and other prominent members of society for public buildings like mosques, schools, and tombs. This lamp was commissioned by Qawsun (originally from Barka, near Samarqand, in present-day Uzbekistan), who was emir (army commander) of the Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalaun, and was most likely intended for the mosque he had built in Cairo in 1329 (now destroyed). The object bears the names of both men and features several of the glass working techniques in which Islamic artisans were skilled, including free-blown glass, enamel, and gilding.

Curator Stefano Carboni explains that "This lamp has an almost globular body with a flared neck and a splayed foot. Six suspension loops are attached to the body. The decoration is divided into nine registers, three on the neck, four on the body, and two on the foot. The narrow bands on the neck depict a background of scrolling leaves, peonies, and flying birds, against which peacocks and parrots turn their necks to look backward; peonies and other vegetal motifs are also depicted on the narrow bands on the body and foot. The largest register on the neck shows an inscription (once gilded) interrupted by three circular medallions, each of which includes a footed red cup set against an orange-yellow background. Three cups identical to this one are depicted inside the large band on the underside of the body, where each is enclosed within a blue lobed cartouche. The main register on the body includes an inscription in blue enamel interrupted by the six rings for suspension." The inscription on the neck is taken from the Qur'an's "Chapter of Light," which uses the metaphor of a glass lamp to describe the divine light of God, stating "God is the Light of the heavens and the earth, the likeness of His light is as a wick-holder..." Carboni and art historian Qamar Adamjee also note that "An unusual feature of this lamp is the artist's signature inscribed around the foot, which may belong to the glassmaker, the painter, or both." Writes Carboni, "whether glassmaker or glass painter, this artist is the only one known to be named as a participant in the making of Mamluk enameled and gilded glass vessels."

Glass, colorless with brown tinge; blown, blown applied foot, enameled and gilded - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Eye Bead

This Eye Bead is typical of ancient Chinese glass. Cultural heritage researchers Jingyu Li, Feng Sun, et al. explain that "The glass compound eye bead is the exquisite embodiment of the glassmaking technology of ancient craftsmen, and is an example of the cultural exchange between China and the West during the Warring States Period." Jewelry designer and historian Simon Kwan writes that "Even though Chinese people knew how to make glass throughout the Western Zhou, Han, and Tang dynasties [about 1046 BC-907 AD], glass continued to be imported from the West during this period. The exact route of this 'glass road' is still not clear today, but it certainly predated the Silk Road by close to a millennium." Chemical analysis demonstrates that many eye beads found at ancient Chinese sites were in fact imported from Central Asia, with the Chinese beginning to produce their own (as evidenced by their higher content of lead and barium) around 500-200 BC, with many found at royal burial sites in Hunan and Hubei, often as coffin decoration, baldrics (belts worn over one shoulder for carrying weapons), and tool inlays.

Li, Sun, et al. write that "Glass compound eye beads are a type of bead decorated with an eye pattern. It is often called dragonfly eye bead in China because it resembles the shape of a dragonfly's eye. In western countries it is called 'compound glass eye bead'." Eye beads first appeared in ancient Egypt around the fourteenth century BC, developing from the glass and precious stone inlays commonly used for the eyes of the Gods in images of deities, and only centuries later became popular in Asia. They often feature decoration of colored dots surrounded by circles on top of a round white dot, representing eyes. Jewelry designer and historian Simon Kwan explains that these beads typically "are not spherical, and many are in the shape of barrels or ovals. [...] The inhabitants of Western Asia saw these eyes as having unmatched power, able to repel evil spirits and bring peace." These beads were fairly expensive and thus owned exclusively by members of the higher classes. Eye beads have been found in many tombs throughout China, and their use does not appear to have been restricted by gender; instead, they appear in tombs of men and women. Kwan writes that, based on the placement of the beads within the burial sites, they "were clearly seen as having mythical powers that could protect the deceased. This concept must have originated from the Western belief in the power of 'gods' eyes' to repel evil spirits."

Glass - Metropolitan Museum, New York City

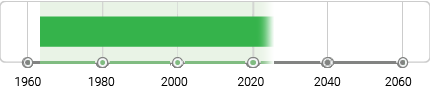

Great East Window

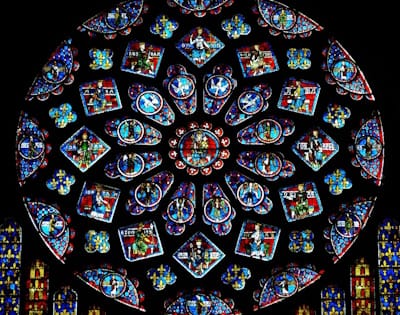

Stained glass is produced by painting glass with pigments that contain powdered glass, firing it so that the paint and glass fuse together, and fixing the segments together with soldered lead "came" (rods). Details and shading can be painted on with black paint after the firing process. During the Gothic and Renaissance periods, this technique resulted in stained glass windows, which were commonly installed in churches around Europe as both a decorative element and as a means of communicating religious messages through imagery as the art lent itself well to representing visual depictions of biblical stories. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, Abbot Suger of St-Denis, who was a key advisor to Kings Louis VI and Louis VII of France, put forth in his writings a number of ideas regarding how church design and decoration could and should be used to honor God and to "brighten the minds [of the parishioners], allowing them to travel through the lights. To the true light, where Christ is the true door." Indeed, light was central to his vision, and stained glass, with its divine prismatic and kaleidoscopic effects, fit perfectly within that vision.

A striking example of early fifteenth-century stained glass can be found at the York Minster Cathedral in England. The Great East Window was commissioned by Walter Skirlaw, bishop of Durham. It was created by John Thornton, a master glazier from Coventry (no doubt with a team of assistants), between 1405-08, and remains the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in Britain, with over 300 glazed panels (in total, about 1,680 square feet of glass) in the International Gothic style. The Great East Window explores a complex biblical narrative, including the beginning of all things (creation, as told in the book of Genesis), and, in the lowest and largest segment, the end of all things (the Apocalypse, as told in the book of Revelation).

Stained glass - York Minster, York, England

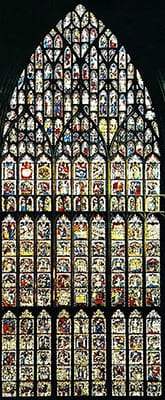

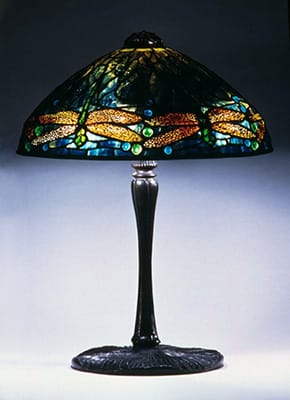

Dragonfly Lamp

Clara Driscoll of Ohio attended the Western Reserve School of Design for Women (now the Cleveland Institute of Art) before moving to New York where she was hired by Louis Comfort Tiffany as the director of the Women's Glass Cutting Department at the Tiffany Glass Company (later known as Tiffany Studios) in 1888. As women were not allowed to work at the company if they were engaged or married, she was forced to leave when she wed the following year. She returned to Tiffany after her husband's death in 1892, before becoming engaged again in 1896, though the engagement was broken off the following year and she once again returned to Tiffany until 1909. Recent research has shown that many lamps previously attributed to Tiffany were in fact the designs of Driscoll or other woman at the company (known as "Tiffany Girls"), like Alice Carmen Gouvy and Lillian Palmié. Despite not being given due credit for her work, Driscoll was, in fact, one of the highest-paid women of her time, earning $10,000 per year.

One piece now known to have been designed and created by Driscoll is the Dragonfly Lamp, which was won a medal at the 1900 Paris World's Fair. In typical Art Nouveau style, the lamp features a botanical theme, with shimmering dragonfly forms standing out against a softly curved, blue and green jewel-toned stained glass lampshade. Driscoll was also the designer of the popular Wisteria, Butterfly, Fern, and Poppy lamp models. In fact, it appears that Driscoll may have been wholly responsible for coming up with the idea for the leaded lamp shades for which Tiffany Studios became so famous, creating the first sketches for them in the 1880s (whereas the company's previous lighting fixtures had used only blown glass and pressed glass tiles). While the men's department was given simpler, more geometric designs to execute, it was the women who were tasked with the floral and botanical patterns, likely as the designs were seen as inherently more "feminine," or as writer Polly King put it in an 1894 article in The Art Interchange titled "Women Workers in Glass at the Tiffany Studios," women possessed "natural decorative taste, keen perception of color, adaptability to the medium employed, and the power to learn from the work about and from the criticisms of the heads of the departments."

Arts writer Jacoba Urist explains that "The Tiffany girls hand-selected tiny shards of colored glass from thousands of glass sheets and were responsible for every facet of design and fabrication - except soldering the cut and foiled pieces of glass together, a task completed by the men's glass-cutting department, since only men were permitted to use heating tools." Journalist Elaine Louie explains that "Besides lamps, both the men's and women's departments also designed and executed stained-glass windows - or at least until 1903. That year, the Tiffany company acceded to a demand by the Lead Glaziers and Glass Cutters' Union, which did not admit women, that only union members - that is, men - be allowed to make the windows. But the women did design and execute small objets d'art, like candlesticks, picture frames and tea screens."

Glass, bronze, and lead - Brooklyn Museum, New York

Garden Landscape

Louis Comfort Tiffany was an American glass artist and designer, and the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & Co. He joined the firm as its first design director in 1902, after having already established himself independently through the founding of the Tiffany Glass Company in 1885 (renamed Tiffany Studios in 1900).

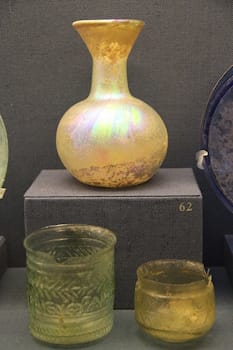

In 1894, Tiffany patented Favrile glass, a groundbreaking process for producing richly colored, iridescent glass. Unlike other iridescent techniques, in which color was applied only to the surface, Favrile glass incorporated metallic oxides directly into the molten glass, allowing color and shimmer to become integral to the material itself. Tiffany developed the process after studying long-buried ancient Roman and Syrian glass - objects he encountered at the Victoria and Albert Museum during an 1865 trip to Europe - and sought to replicate their luminous yet opaque qualities. Favrile glass earned Tiffany a Grand Prize at the 1900 Paris Exposition and became central to his artistic vision.

The innovation provided Tiffany with a material capable of transmitting color and texture without reliance on surface painting. As the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art notes, Favrile "enabled form to be defined by the glass itself rather than by painting onto the glass." One notable example is Garden Landscape (c. 1905-15), a Favrile glass mosaic composed of transparent tesserae backed with metal leaf. The work depicts a tranquil pond bordered by swans, trees, and distant buildings beneath a softly hued pink and blue sky. It may have served as a preliminary study for Dream Garden (1915), the monumental site-specific mosaic designed by Maxfield Parrish in collaboration with Tiffany Studios for publisher Edward Bok and installed in the lobby of the Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia. Garden Landscape remained on view in the Tiffany Studios showroom until its closure in 1932.

Favrile glass was used across Tiffany's wide-ranging output, from stained glass windows to mosaics created for both religious and secular interiors. In 1901, Tiffany emphasized that "an important part of the work of the studios is the artistic treatment of artificial light." His early experiments with glass stemmed from frustration as an interior designer, unable to find materials that met his aesthetic demands. Around 1878, he began producing glass himself, eventually developing what would become known as the "American Style" of stained glass.

As arts writer Lucija Bravic explains, Tiffany and his team of artisans utilized inexpensive recycled glass - often sourced from jelly jars and bottles rich in mineral impurities - which enhanced depth and visual complexity. Equally transformative was Tiffany's adoption of the copper foil technique, which allowed glass pieces to be soldered continuously along their edges rather than only at intersecting points, as in traditional lead came construction. This method enabled unprecedented precision and intricacy, making possible the naturalistic detail and flowing forms characteristic of Tiffany's Art Nouveau designs.

Favrile-glass mosaic - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Blue/Orchid Square Descending Form

Harvey Littleton of Corning, New York, is considered the "Father of the Studio Glass Movement." During the 1930s, when Littleton was a teenager, his father, a physicist, worked as head of Research and Development at Corning Glass Works, and young Harvey spent a great deal of time at the laboratory and factory. Harvey first went into ceramics but soon turned to glassblowing. Around 1960, he worked with glass research scientist Dominick Labino to design a smaller furnace for glassblowing, which would allow individual artists and small collectives to have their own studio furnaces, rather than relying on the use of larger industrial furnaces. In 1962, Littleton ran his first glassblowing workshop at the Toledo Museum of Art, at which he debuted the new, smaller furnace, and the Studio Glass movement was born. Littleton paved the way for individual artists to explore and experiment with glassblowing in their private spaces, launching a new wave of contemporary glass art production, and promoting glass art as a sculptural form in its own right.

In his own practice, Littleton began, as many glass artists do, by producing vessels. His breakthrough came in 1963 when, after smashing one of his pieces in frustration, he set about remelting it into a new, nonfunctional object. He explains that "it aroused such antipathy in my wife that I looked at it much more closely, finally deciding to send it to an exhibition. Its refusal there made me even more obstinate, and I took it to New York [...] I later showed it to the curators of design at the Museum of Modern Art. They, perhaps relating it to some other neo-Dada work in the museum, purchased it for the Design Collection." At that point he dedicated himself to his series of "Prunted," "Imploded," and "Exploded" forms throughout the 1960s. Then, in the 1970s, he began blowing glass tubes that he bent over themselves while still hot, allowing gravity to drag them downwards. He is perhaps best known for his Topological Geometry (1983-89) series of looping and twisted sculptures, composed of strands of various brilliant colors encased in thick layers of clear glass, like Blue/Orchid Square Descending Form (c. 1987).

Hot-formed glass, Two pieces - Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo, New York

Three Graces Tower

American Studio Glass artist Dale Chihuly attended Harvey Littleton's glassmaking workshop in 1962 after which he became a noted leader in the field, creating vibrant, at times bizarrely shaped, and often enormous sculptural glass works. He holds the record for the largest glass sculpture ever made, with his 2,100 square foot Fiori di Como (1998), for which he installed over 2,000 brightly colored flower-shaped glass sculptures on the ceiling of the lobby of the Bellagio Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. His glassmaking practice is indebted not only to Littleton, but also to the Venetian glassmakers on the island of Murano, as, in the early 1980s, he earned the honor of being the first American glass artist to be invited to apprentice at one of the island's glass factories. Chihuly went on to establish the Glass program at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington State.

Since 2001, Chihuly has been working on his Garden Cycle, installing site-specific glass sculptures at botanical gardens around the United States as well as in countries like England, Singapore, and Australia. One such work is Three Graces Tower, installed in 2016 at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens in Georgia. The piece features the same sort of floral figure found in his Fiori di Como, a broad, rounded, rippled, and asymmetrical form, inspired in part by Islamic blown glass from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, which he calls the "Persian." He first arrived at this form in 1986 through a process of experimentation. He explains, "As I experimented with hot glass and its organic properties, my work naturally began to look like something that came from the sea or from a garden. While I don't always have specific forms in mind going into the process, my work often ends up looking like part of our natural environment. I think that is because I have learned over many years what the glass wants to do organically." Artist, curator, and art historian Tina Oldknow writes that "The sources of [Chihuly's] Persians are classical Greek, Persian, Byzantine, Islamic, Venetian, and art nouveau, together representing an incredibly fertile palimpsest of ideas and influences. [...] The impetus, however, is the marvelous - la merveille - that other, magical world where the source of wonder and delight reside."

Blown glass - Atlanta Botanical Gardens

Beginnings of Glass Art

Ancient Glass Art

The production of art using glass can be traced back as early as 5000-2500 years ago, when the Egyptians, Assyrians, Mesopotamians, and Mycenaeans would cast melting glass in open molds using a mixture of silica-sand, lime, and soda. Around 1500 BC, the Egyptians developed faience, an earthenware made by crushing quartz, mixing it with plant ash, heating it in clay containers at a low temperature, and then re-crushing it with coloring agents (cobalt for blue, copper for red, tin or lead for white, and manganese for violet) and re-heating it at a higher temperature. Evidence shows that the Egyptians were exporting glass as early as the year 13 BC, and they were known for their red glass, a difficult color to produce. It is believed that as the Egyptians expanded out, especially toward the Mediterranean, they encountered artisans in other areas whom they brought back to work as slaves, producing glass art for the upper classes.

In all of these cultures, for the most part, glass art (including beads and jewelry, mosaics, figurines, furniture inlays, and vessels) was reserved primarily for royalty, and has been found at the burial sites of elite individuals to a far greater extent than those of common folk. Indeed, glassmaking is costly, as it requires a significant amount of fuel to feed the furnaces. Particularly in Egypt, it appears that glassmaking techniques were a highly guarded royal secret. Meanwhile in early ancient Greece, it appears that there were no glass production centers, and the Greeks instead imported glass products from Egypt. It wasn't until the Classical and Hellenistic periods that a Greek glass industry developed, with many artisans specializing in complex colored mosaic patterns.

In Ancient Asia, faience and glass products were manufactured beginning around 2000 BC in the West. In China, glass production dates to about 1000-500 BC, and the Chinese pioneered lead-barium silicate glass, as can be found in the blue inlay of the bronze sword of King Goujian (c. 771-476 BC), which was found in a tomb in Hubei in 1965. Many other ancient Asian glass artifacts are beads (especially polychromatic "eye beads," often found at burial sites), with vessels being less common there than in other world cultures of the time. Monochromatic green glass was often used to mimic jade, as found on objects like "glass garments" (glass burial suits), "bi disks" (flat disks used for ritual purposes), carved pendants, and sword accessories. The Silk Routes facilitated exchange of glass products between Asia and the West.

The earliest glassmaking manuals come from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal and date to around 650 BC. Then, around the first century BC, the technique of glassblowing was developed, most likely by the Phoenicians, allowing artisans to mold glass into any shape they wished and to achieve higher levels of transparency and thinness. Glassblowing was a preferred technique of the ancient Romans, who experimented extensively with incorporating other techniques such as painting, gilding, and encasing their glass with layers of color. They further developed the millefiori technique for producing flower-mosaic-like patterned glass, which had first been invented by the Egyptians. The Romans also continued to produce glass mosaics, vessels, and other objects with cold working techniques.

Glass Art in the Middle Ages

With the fall of the Roman Empire in AD 476, the Mediterranean region was faced with economic instability and the production of glass art declined throughout the Middle Ages. However, at the same time, the Muslim territories were expanding and prospering, and there glassmaking began to flourish from the seventh to fourteenth centuries, peaking in the tenth and eleventh centuries. According to art historians Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, "The three most prolific excavated sites that have yielded glass in the Islamic world are Fustat (Old Cairo) in Egypt, Samarra in Iraq, and Nishapur in northeastern Iran." Influenced by earlier developments in Egypt and the Mediterranean, glass artists in the Middle East produced glass objects with traditional Islamic imagery and decorative designs, and innovated further in the techniques of mosaic, glass carving, relief cutting, gilding, trail application (the addition of fine details using molten glass), mould- and free-blowing, and lustre painting (applying copper or silver pigments to glass), as well as in experimentation with different ingredients for producing glass.

Although the Middle Ages saw a sharp decline in glassmaking in Europe, one particular invention took hold: stained glass. Curator and critic William Warmus writes that stained glass "satisfied an urgent need for lighted (but also sheltered) space within the great (but at times glacial) cathedrals that were rising throughout Europe. Abbé Suger, who is credited with the development of the Gothic style, thought of stained glass as perfect for symbolizing the entrance of spiritual light into the hearts of mankind. Thus, glass became a premier art form, an atmospheric art full of mystery for the most spiritually inclined, a cinematic art capable of telling stories to everyman. Indeed, Suger (who lived in the eleventh and twelfth centuries) asserted that "God is light," drawing inspiration from fifth- and sixth-century Greek author, Christian theologian, and Neoplatonic philosopher Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who compared God to the light of the sun, and presented a metaphysical theory of light in his writings on philosophy and aesthetics. For Suger, the manipulation of light with stained glass thus allowed for humans in the material world to experience a taste of the divine realm.

Much of what we know about medieval stained glass comes from the writings of twelfth-century German Benedictine monk, artist, and metalworker Theophilus, who, in his De Diversis Artibus (c. 1110-40), wrote a detailed account of the processes of making stained glass, as well as wall metalworking, painting, manuscript illumination, organ-building, and ivory carving. The use of stained glass as a decorative architectural element in churches continued throughout the Renaissance. The stained glass process involves cutting glass to shape, painting it with pigments that contain powdered glass, firing it so that the paint and glass fuse together, and fixing the segments together with soldered lead "came" (rods). With the colonization of countries in South America, Asia, and elsewhere, much glass art was introduced to these countries via stained glass windows in Baroque churches, and other glass objects brought over from the colonizing countries.

Venetian Glass

With the development of the Silk Routes, and the establishment of a trade treaty between Venice and the Mongol Empire in 1221, Venice became an important hub for trade, cross-cultural exchange, and industry. One industry for which the area became famous was glassmaking, in part because of the availability of necessary materials, like wood, sand, and other minerals. The Venetian Island of Murano emerged as an important center for luxury glass production during the Renaissance, and remains so today, being considered the birthplace of modern glass art, particularly for blown glass. It was also on Murano that significant advances were made in the technologies of glass mirrors and telescopes (both in the sixteenth century).

Giorgio Spanu, founder of the Magazzino Italian Art museum and research center, explains that "In 1291, for a number of reasons, including severe labor regulations in Venice, the doges were forced to move glassmaking from the city of Venice to the island of Murano. The official reason for this relocation was the fire hazards created by the furnaces. In reality, it was easier for the Venetian authorities of the Maggior Consiglio to regulate not only the diffusion of glass throughout the world but the profession of glassmaking itself. [...] The art of Venetian blown glass had its Golden Age in the sixteenth century. Thin-stemmed chalices, finely shaped bowls, and tiny covered baskets were executed according to the designs of the most celebrated painters of the time."

Glassblowing techniques developed on Murano include incalmo (fusing two or more blown glass elements), reticello (glass with a fine, net-like pattern of filigree canes), zanfirico and latticino (glass with more complex, spiraling filigree patterns), cristallo (colorless blown glass that looks like crystal), and calcedonio (glass with metal oxides used to create marbled patterns similar to opal or agate). For the most part, the glass fornace (literally "furnaces," but referring to the factories as a whole) on Murano were intended to be highly secretive, guarding their trade secrets, and passing them down through families from generation to generation. A number of Muranese glassblowers, however, relocated elsewhere in Italy, and to countries like France, Austria, Belgium, Spain, and Sweden, and took on foreign apprentices, allowing for the dissemination of traditional Venetian techniques abroad.

Factory Glass

With the Industrial Revolution came the mechanization of glassmaking processes, with machinery like steam-powered cutting wheels making production more efficient and less costly. Despite attempts by Great Britain to discourage American glasshouses from opening (hoping instead for raw materials to be sent back to England from the colonies, and for the finished products to then be bought back), several glasshouses opened in the United States in the mid-eighteenth century, including one built by Caspar Wistar in Salem County, New Jersey, in 1739, and the New Bremen Glassmanufactory in Frederick, Maryland, founded in 1785 by German glassmaker John Frederick Amelung. Curator Jane Spillman has even called glassmaking "America's first industry," with the first glass workshop being founded in 1608 in Jamestown, Virginia.

Common glass objects produced in factories included bottles, flasks, and tableware. Spillman explains that "To make it more quickly and inexpensively, glass began to be blown into full-size, multipart metal molds that gave both pattern and shape to the finished object. This was a technique that had been developed by the Romans but had fallen out of use in medieval times until it became popular again in the early nineteenth century. [...] It was not until the 1820s, when the idea of mechanically pressing glass into molds was conceived, that the American glass industry achieved its greatest success." In 1829, after attending an exhibition of American manufactured goods in New York City, English writer James Boardman wrote that "the most novel article was the pressed glass which was far superior, both in design and execution, to anything of the kind I have ever seen in London or elsewhere."

Glass artist Daniel Pruitt writes that "As time progressed, it became widely assumed that glass, especially blown glass, could only be made in a factory with teams of skilled workers to produce the basic forms in large quantities. These factories were thought to assure quality." In the 1900s, Toledo, Ohio, and Corning, New York emerged as major production centers for both functional and artistic glass pieces. Toledo has even earned the title of "Glass Capital of the World." Though pressed glass dominated, on the East Coast of the United States some factories also specialized in cut and engraved glass, originally imitating English and European styles, but eventually, as Spillman writes, developing "their own style of what was termed rich cut glass, employing very thick blanks and very deep cutting, the results causing the glass to sparkle in artificial light." Rich cut glass objects soon became extremely popular as wedding gifts.

Art Glass

From about 1875-1945, many glassmakers in Europe and the United States sought to produce highly innovative, decorative, and elaborately colored, patterned, and textured glass objects (such as lamps, vases, bowls, and figurines), intended to be displayed in parlors. Art Glass specialist Nick Dawes explains that "The Western Art Glass movement really begins in Stourbridge, England at the firms of Thomas Webb and Stevens & Williams and involves Victorian efforts to recreate ancient glassmaking techniques used up to the late Roman Empire and generally lost through the European Dark Ages. This was mainly "cameo" (Roman) glass, first recreated in England, then "pate-de-verre" (earlier, Egyptian), revived in France." Art glass was in part catalyzed by the large international expositions and World's Fairs that promoted new trends in decorative tastes. In Europe, Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) emerged as a leader in glassmaking during the nineteenth century, particularly when it came to iridescent glass, and "ruby glass," the signature creation of Bohemian glass manufacturer Moser Glass, which achieved a vibrant red color through the mixing of precious gold into the glass.

Much Art Glass was produced in the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles. M. S. Rau Fine Art explains that "Art Nouveau was a design movement intended both to elevate the status of the craft-based artisan while also rebelling against the sterility of industrialism and the academic system of fine art. The style embraced the elegance of the natural world and sought to convey movement. This revolution in artistic ideals permeated nearly every facet of the decorative arts, and its sinewy, flowing lines often lent themselves well to the molten glass required for the glassblowing process." Leading French glass designer René Lalique produced vases, lamps, bowls, car hood ornaments, and more, in both the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles, and often employed the lost wax casting method (commonly used by bronze sculptors) to create unique glass pieces.

Also in France, glass artist Emile Gallé, an avid botanist, created glass pieces in the Art Nouveau style, drawing inspiration from the large collection of plant and insect specimen he collected. Meanwhile, American glass artist Louis Comfort Tiffany became known for his stained glass windows and lamps, as well as glass mosaics, blown glass, and glass jewelry, with floral/botanical themes. He patented "Favrile glass" (a type of iridescent glass that sought to mimic long-buried ancient Roman and Middle Eastern glass pieces) in 1894, and it won him a grand prize at the Paris Exposition of 1900. In 1885, he founded the Tiffany Glass Company (which became Tiffany Studios in 1900). There, on and off from about 1888 until 1908, Clara Driscoll of Ohio served as the head of the Women's Glass Cutting Department, and recent research has revealed that she and a number of other female designers (known as the "Tiffany Girls") were behind several designs preciously attributed exclusively to Tiffany.

Tiffany's father, jeweler Charles Lewis Tiffany, founded Tiffany & Co. in New York City in 1837. The company started out by selling high-quality Bohemian glass, but by 1902, when the younger Tiffany became the company's first Design Director, was producing its own Art Glass pieces. Other companies that became known for their Art Glass included Fabergé (founded by Russian jeweler Gustav Fabergé in 1842, and taken over by his son Peter Carl Fabergé in 1872), Daum (founded in 1878 in Nancy, France by glass artist Jean Daum), and Steuben Glass Works (founded in 1903 by glass artists Frederick Carder and Thomas G. Hawkes in Corning, New York).

The Studio Glass Movement

In the early 1960s, the development of small, inexpensive furnaces for private studio use changed the glassmaking game, allowing individual artists and small collectives to design and produce glass art, seeing the process through from start to finish. In March and June of 1962, University of Wisconsin ceramics professor Harvey Littleton, who had worked with glass research scientist Dominick Labino to develop the smaller furnaces, and whose father was the head of research at Corning Glass Works, ran glassblowing workshops in a garage on the grounds of the Toledo Museum of Art, effectively launching the American Studio Glass Movement. One of the students who attended the workshops, Marvin Lipofsky, went on to start glass programs at the University of California at Berkeley in 1964 and at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in 1967. Another student, now-renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly, started a glass program at his alma mater, the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), in 1969, and several other American institutions soon had glass programs of their own.

Curator Bobbye Tigerman writes that "Inspired by studio ceramists, who had expanded the scope of their work to include sculpture as well as useful objects, glassmakers no longer felt bound by functional imperatives and embraced the potential of glass for artistic expression. Thus began a fertile period of experimentation that continues today, in which glass artists have often worked on a massive scale and employed a variety of techniques to highlight the brilliance, transparency, and visceral power of glass." Indeed, Studio Glass artists focus on glass as an artistic medium, prioritizing aesthetics over functionality, often producing glass sculptures, though some, such as Chihuly, do also produce functional objects like lamps and drinking vessels. Other notable Studio Glass artists inspired by Littleton include Sam Herman, Fritz Dreisbach, Tom McGlauchlin, Bill H. Boysen, William Morris, Paul Stankard, Dante Marioni, Sonja Blomdahl, Mary Ann "Toots" Zynsky. These artists employ the entire gamut of glass working techniques to produce their art.

The Studio Glass movement has developed into an international phenomenon, spreading to Europe, Asia, and elsewhere. In the Czech Republic, married artists Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtova were pioneering studio glass art around the same time as Littleton and Labino were working in the United States. Other European countries were soon to catch up. Dutch artist Sybren Valkema, who began Workgroup Glass at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam, is considered one of the founders of the European Studio Glass (or Vrij Glas (Free Glass)) movement (along with Dutch artist Erwin Eisch). In 1967, Valkema organized the first Vrij Glas exhibition at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Gemeentemuseum Arnhem, and Groninger Museum, which included work by Eisch, Littleton, Lipofsky, Sam Herman, and Valkema himself. The following year, Littleton invited Valkema to teach a class on European Glass Techniques (in which he introduced the use of color rods) at the University of Wisconsin. In the early 1970s, American glass artist Bill Boysen toured around Australia with a mobile studio, giving glassblowing demonstrations to hundreds of people in eight states, helping to launch the country's own Studio Glass movement. In China, Studio Glass was pioneered by Loretta H. Yang and Chang Yi around 1987 at the first contemporary Chinese liuli (glass) art studio Liuligongfang.

Concepts and Styles

Coldworking Glass

As opposed to hotworking glass, which involves the use of a kiln, a furnace, or a torch, coldworking refers to a range of techniques (such as grinding, polishing, cutting, engraving/etching, sandblasting, and stippling) used before and after the hotwork when the glass is cooled. Coldworking serves several purposes, including polishing the glass and smoothing edges and surfaces, creating a textured surface, and exposing underlying layers of glass. Etching (or engraving) is a common coldworking technique that involves the use of acid, sandblasting, drills, or other sharp tools to carve into the glass. Cut glass is similar to etching or engraving but involves cutting deeper into the glass to create deeper textural elements, and usually also involves re-polishing the glass (whereas with engraved glass, the surface is often left matte or "frosted"). Gilded and Silvered glass (mirrors) are also cold working techniques, made by coating the back surface of a glass panel in metal leaf using gelatin adhesive.

Warmworking Glass

Warmworking glass refers to a range of warm glass techniques that require a kiln (which reaches temperatures between 1400-2000°F (760-1100°C)). These techniques include fusing (heating two or more pieces of glass to join them), slumping (heating glass over an object so it takes on the shape of that object), kiln-casting (vertically heating glass into the void of a refractory mold below, similar to the lost-wax casting method in bronze sculpture), and pate-de-verre (literally "glass paste," which involves heating "frit" (crushed glass granules) and blending them with a binder to create a paste, which is then applied to the interior of a mold).

Hotworking Glass

Hotworking refers to techniques for working molten glass at temperatures above 2000°F (1100°C). Lampworking is a hot glass technique in which a torch is used to melt the glass and shape it into different forms. Other hotworking techniques include high-temperature glass casting (melting glass into a mold in a furnace), and glassblowing (placing a parison (bubble) of molten glass at the end of a blowpipe and then inflating and manipulating the glass to create various forms).

Though glassblowing was probably first invented by the Phoenicians, it has been a popular glass working method around the world for millennia, and in Syria, glassblowing is now recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. Today, Studio Glass artists favor glassblowing as it results in entirely unique pieces, with no two being identical, and the possibilities of form and thickness are infinite. Glassblowing is dangerous and challenging, as the glass must be worked quickly, before it cools and hardens.

Enameled Glass, Stained Glass, and Glass Mosaics

Enameled Glass is made by applying colored vitreous enamel (powdered opaque glass) to a glass surface (though it can also be applied to metal and ceramics) and then firing it in a kiln so that the enamel liquifies, before cooling and hardening into a smooth, highly durable and heat-resistant, opaque or translucent coating. Stained glass is a similar process, but which involves the application of a mixture of powdered glass, metal oxides (as colorants), and a liquid binder to the base glass surface, resulting in a more transparent effect. Though the term "stained glass" technically can be applied to any colored glass (including enameled glass), today the term most commonly refers to decorative, translucent windows (such as those found in many catholic churches around the world), as well as objects like Tiffany lamps. Often, additional details (such as shading) are added onto stained glass images using vitreous enamel.

Stained glass artist Robert W. Sowers explains that "The singular colour harmonies of the stained-glass window are less due to any special glass-colouring technique itself than to the exploitation of certain properties of transmitted light and the light-adaptive behaviour of human vision. [...] The static elements of the glass and its architectural setting are modified by the element of change inherent in natural light. A seemingly endless spectrum of changes in the appearance of stained glass is a result of the changes in the intensity, disposition, atmospheric diffusion, and colour of natural daylight. The luminous life of stained glass, therefore, can best be observed by watching the organic effect of light on the window through the course of a day. [...] Insofar as stained glass may be considered an art of painting, it must be considered an art of painting with light."

Glass mosaics follow a similar process to stained glass (and actually predate stained glass), with the difference being that while stained glass segments are attached by lead came (rods), allowing for light to pass through, glass mosaics are affixed with an adhesive to a (usually opaque) substrate, such as wood or concrete, with the gaps filled in with grout, therefore not necessarily allowing for the passage of light through glass.

Millefiori Glass

Millefiori (Italian for "thousand flowers") refers to a style of patterned glass created by the layering of small glass rods (or "canes") which are then fused together, and cut through the mid-section, producing distinctive flower-like patterns (known as "murrine"). Though today, the Venetian island of Murano is most famous for millefiori, the technique, in fact, can be traced back to the ancient Romans, Phoenicians, and Egyptians and was also popular in Islamic glass art during the Middle Ages.

Later Developments - After Glass Art

Today, glass art continues to be produced around the world, with artists using a wide range of ancient and modern techniques, for both functional objects and art such as sculptures. Glass artists like Swedish artist Fredrik Nielsen, Japanese artist Rui Sasaki, Danish artist Stine Bidstrup, Dutch artist Krista Israel, and American artists Josiah McElheny and Christine Tarkowski blend traditional glass working methods with a contemporary aesthetic, offering a glimpse into what glass art of the future may look like. Japanese glass artist Ayako Tani has pioneered what she calls "calligraphic glass" or "lamp work calligraphy," in which she uses molten glass as "ink," translating the ancient Japanese calligraphy tradition to a new medium.

Meanwhile, other contemporary artists are using glass to explore present-day themes and concerns, like Costa-Rican glass artist Juli Bolaños-Durman, who uses recycled glass in his eco-conscious glass sculptures, American glass artist Deborah Czeresko, who uses her glassmaking process to address "the gendering of occupation and object through the lens of a mythical Renaissance Venetian glass maestro who is female," and Irish glass artist Karen Donnellan, who recently authored "Blow Harder: Language, Gender, and Sexuality in the Glass Blowing Studio," and who explores feminist themes in glassblowing.

3D glass printing was pioneered in 2016 by a team of MIT researchers, called Mediated Matter, as part of a project called G3DP, the first products of which were artistic vessels. The technology is still in the experimental phase, so far having been used mainly for smaller objects and sculptures, though it may not be long until we see larger glass objects being 3D printed.

Many artists known for working in more traditional media like painting and sculpture are also beginning to experiment with glass, like American artist Kehinde Wiley, who became famous for his portraits of young African-American men in the style of neoclassical and Renaissance masterpieces, and who has turned in the last decade to producing similar works in stained glass. American sculptor Maya Lin, whose father was active in the early Studio Glass Movement in 1960s Ohio, has also used glass in recent artworks, like her 1993 installation Groundswell which repurposes recycled glass, and her 2021 sculpture Decoding the Tree of Life, which features over 15,500 handblown glass spheres affixed to a base structure of twenty-two cast stainless steel branches welded together to form a tree.

Glass art is now receiving greater attention from major institutions, for instance with the Smithsonian Museum of American Art hosting an exhibition titled New Glass Now in 2021, which featured "makers from historically underrepresented communities within the glass world [such as] women, artists of color, and members of LGBTQ+ communities," including Argentinian glass artist Andrea de Ponte, queer Hungarian artist Tamás Ábel, and artist James Magagula of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland). Also, in 2023, the Wichita Art Museum hosted Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass, an exhibition of glass art by Native American and Pacific Rim artists. The Corning Museum of Glass has also emerged since 1951 as a leading institution with the world's largest collection of glass, featuring over 50,000 objects from the past 3,500 years.

Useful Resources on Glass Art

- World of Glass: The Art of Dale ChihulyBy Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan

- Charles J. Connick: America's Visionary Stained Glass ArtistBy Peter Cormack

- Rowan LeCompte: Master of Stained GlassOur PickBy Peter Swanson

- The Art Glass of Louis Comfort TiffanyOur PickBy Paul Doros

- Louis Comfort Tiffany: MasterworksBy Camilla Bédoyère

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Art Glass of the Martin House ComplexOur PickBy Eric Jackson-Forsberg

- Harvey K. Littleton: A Life in GlassBy Joan Falconer Byrd

- Glass Art: 112 Contemporary ArtistsBy E. Ashley Rooney and Barbara Purchia

- Mid-Century Modern Glass in AmericaOur PickBy Dean Six

- Looking at Glass: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and TechniquesOur PickBy Catherine Hess and Karol B Wight

- Stained Glass: Radiant ArtBy Virginia Chieffo Raguin

- Masterworks of Art Nouveau Stained GlassBy Arnold Lyongrun and M. J. Gradl

- Venini: The Art of GlassBy Federica Sala

- How to Look at Stained Glass: A Guide to the Church Windows of EnglandBy Jane Brocket

- Stained Glass: Masterpieces of the Modern EraBy Andres Gamboa

- Murano Magic: Complete Guide to Venetian Glass, Its History and ArtistsBy Carl I. Gable

- Glass of the Sultans: Twelve Centuries of Masterworks from the Islamic WorldOur PickBy Stefano Carboni and David Whitehouse

- Glass: Art Nouveau to Art DecoOur PickBy Victor Arwas

- Glass: A Short HistoryBy David Whitehouse

- Visual Art in GlassBy Dominick Labino

- Stained and Art Glass: A Unique History of Glass Design & MakingBy Judith Neiswander and Caroline Swash

- Seeing Renaissance Glass. Art Optics and Glass of Early Modern Italy 1250-1425By Sarah Dillon

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI