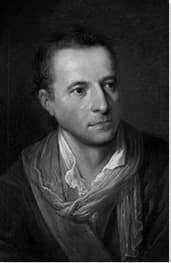

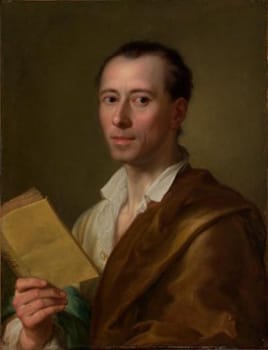

Summary of J.J. Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann is one of the founders of the discipline of art history, and the father of Hellenic archaeology. His crowning achievement, History of Ancient Art (1764), has remained a staple text in Greco-Roman art history for over three centuries. Through his archaeological surveys, moreover, Winckelmann had established an empirical methodology for studying the past (this at a time when archaeology was considered little more than the "occupation of noble gentlemen"). Winckelmann's unswerving conviction that Greek antiquity represented the apex of human accomplishment offered a standard by which all artistic excellence should be measured and provided the theoretical impetus for the birth of the Neoclassical movement. Having moved from Prussia to Italy, Winckelmann came closest to the socio-political freedoms on which he placed such a high value both in life and in art. And while homosexuality was widely considered a "crime against nature", Rome offered a relatively safe environment for Winckelmann to pursue his clandestine love interests.

Accomplishments

- Seven years in the making, The History of Ancient Art presented art history in terms of a linear periodization over four stages of Greek art: "Straight and Hard", "Grand and Square", "Beautiful and Flowing" and "Imitative". By basing his arguments on archaeological findings, Winckelmann earned a reputation as a serious authority and tastemaker who was well placed to offer a new direction for art criticism and connoisseurship.

- Although he had established a firm analytical model for Greco-Roman art history and criticism, Winckelmann writings still found room for strong aesthetic responses to art. By placing great emphasis on the emotional aspect of art connoisseurship, Winckelmann extended art history and criticism beyond thematic and/or authorial associations, as exemplified earlier by Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550 and 1568).

- Winckelmann's study of classical Greek nudes was underscored with a patent homoeroticism that revealed itself in his writings on the male nude and the revival of the ancient ideal of love between males. He positioned the male body as the true vehicle of beauty rather than simply a symbol of virtue and heroism. In this respect Winckelmann had followed Plato's idea that it was through the contemplation of the beauty of youths that would lead to a higher spiritual enlightenment.

- Winckelmann's edict that the finest art should be imbued with a "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" was carried forward by the Neoclassical movement. Their adherence to the concept of the "beau idéal" ("ideal beauty"), and as exemplified by the marble sculpture, Apollo del Belvedere (c.120-140 ACE), contrasted to the decorative excesses of Rococo and Baroque art.

The Life of J.J. Winckelmann

Historian Michael Preston Worley wrote, "Winckelmann created the discipline of art history as we now know it, transforming the traditional, dry archaeological description into fervent and poetic art criticism that expressed his love of Greco-Roman beauty".

Ideas and Analysis by J.J. Winckelmann of Important Artists and Artworks

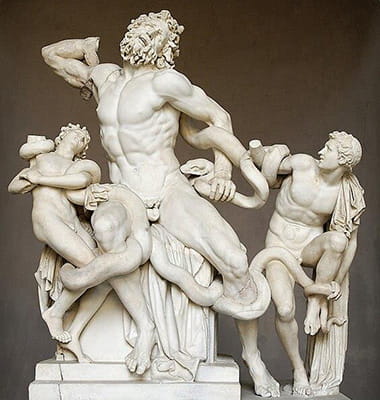

Laocoön and His Sons (2nd century BC)

Laocoön holds a special place in art history due to its masterful depiction of human emotion and physicality. It is one of the most influential ancient works in the history of art and has inspired many artists. The statue was discovered in 1506 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome by a farmer working in his vineyard. It is thought that the Laocoön was just one of a number of such artworks that had been abandoned or forgotten and later buried under new buildings and streets. Amongst the first people to study the statue were Michelangelo, and architect Guiliano da Sangallo, and was, on their recommendation, purchased by Pope Julius II (it remains in the collection of the Vatican to this day).

The sculpture draws its name from the Trojan priest who, with his sons, was slain by sea serpents before the Greeks infiltrated Troy (hidden within the famous wooden horse). Likely created around the first century BC by the artists Hagesandros, Polydoros, and Athenodorus of Rhodes. It captures the dramatic struggle of Laocoön and his sons as they are ensnared by the serpents. Since its discovery, Laocoön has been presented as model of artistic excellence. Winckelmann expressed particular fascination with the contrasting emotions evoked by the sculpture. While viewers are most likely moved by the pain and agony of Laocoön's body, they can simultaneously admire his physical perfection. Winckelmann articulated this dual response thus: "In the pain of Laocoön you can see his annoyance, as though at the suffering he is not worthy of, in the wrinkling of his nose, and also his fatherly compassion swimming over his eyeballs like a dull mist. These beautiful qualities in a single impression are like an image expressed in one word by Homer".

Winckelmann argued that classical Greek sculpture embodied the ideal of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur", and was, in his view, the defining ideal of antiquity. However, critics such as the philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, took issue with this interpretation. He argued that since Laocoön embodies an undeniable dramatic and emotional intensity it is therefore at odds with the serenity associated with classical beauty. Meanwhile, Germany's literary great, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe - who was one of Winckelmann's greatest's champions and admirers - also admired the sculpture's ability to animate its viewers' emotions. He wrote, "the ancients [...] avoided not so much what was ugly as what was false. This is to me the proof that the excellence of the ancients is to be sought in something other than the creation of beauty".

Greek Parian marble - Pio-Clementine Museum, Vatican City

Apollo del Belvedere (c.120-140 AD)

Apollo del Belvedere is an exquisite 7 feet tall marble sculpture. It shows Apollo, the Greek god of the sun and music majestically posed as a standing archer who has just killed a serpent. This masterpiece, believed to be a Roman copy of a lost Greek original by the fourth century BC sculptor, Leochares, embodies the ideals of classical beauty and harmony that Winckelmann championed. The figure's flawless anatomy, graceful proportions, and serene expression were for him the epitome of the aesthetic principles of the period. The Apollo del Belvedere's significance lies, moreover, in its profound influence on the revival of classical art during the Renaissance when it served as an exemplar of the classical ideal that artists and scholars were seeking to emulate.

London's Sir John Soane's Museum notes that, "The Apollo Belvedere was admired by many artists - Michelangelo is said to have based the face of Christ in his Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel on it - and regarded from the mid-18th century both as the greatest sculpture of antiquity and the epitome of male beauty. Its complex contrapposto stance, showing the figure both frontally and in profile, was particularly admired". Winckelmann wrote, "In gazing upon this masterpiece of art, I forget all else, and I myself adopt an elevated stance, in order to be worthy of gazing upon it. My chest seems to expand with veneration and to heave like those I have seen swollen as if by the spirit of prophecy, and I feel myself transported to Delos and to the Lycian groves, places Apollo honored with his presence - for my figure seems to take on life and movement, like Pygmalion's beauty".

Numerous academics have noted that Winckelmann's description of Apollo as "sublimely superhuman" and with a physique that evokes "the charming manliness of maturity with graceful youthfulness [that] plays with soft tenderness on the proud build of his limbs", was governed by his own sexuality. Historian Alex Potts has noted that, "it is striking that Winckelmann singled out the Apollo Belvedere, the epitome of masculinity, as the object of his sexually charged encomium, instead of a classically desirable female body such as the Venus de' Medici - a sculpture noted for its history of exciting lewd behavior from observers. [...] Winckelmann's justification for such an eroticized reading of the sculpture is premised on Apollo's depicted killing of the Pythian serpent, which accorded him male agency as a heroic figure for the viewer to identify with. This prevented the Apollo from being reduced to a passive recipient of the gaze, and consequently guarded Winckelmann's description from the imputation of overt homosexuality".

Marble - Vatican Museum, Vatican City

The Apollo Barberini (1st-2nd century CE)

The Apollo Barberini, often referred to as the Barberini Muse, is a controversial piece within Winckelmann's writings. Initially, he suggested that the sculpture was one of the oldest statues in Rome, dating it to the transition between the archaic (roughly, 8th to 6th centuries BC) and high classical periods (roughly 450-400 BC) due to its combination of archaic stylization and classical simplicity. This assessment underpinned Winckelmann's broader effort to classify and understand the evolution of Greek art forms. Indeed, he framed the Apollo Barberini as the embodiment of the ideal forms that Greek art aspired to, thereby reflecting the blend of naturalistic detail with the idealized forms that characterized high Classical art. However, subsequent research has revealed that the Apollo Barberini is actually a Greco-Roman variation (rather than a Greek original).

Potts writes, "Winckelmann himself appeared to realize the difficulty of distinguishing works of the Greek high and beautiful phases from later imitations or reinterpretations. [...] This uncertainty was fundamentally a tension at the heart of his project, which sought to reconcile a systematic, theoretical explanation of the development of styles with a compromised body of evidence". However, in The History of Ancient Art, Winckelmann seemed to acknowledge this difficulty when he said that The Apollo Barberini "arouses so much the greater longing for what is lost, and we examine the copies we have with greater attention than we would if we were in full possession of the originals. In this, we are often like individuals who wish to converse with spirits and believe they can see something where nothing exists". Despite his "misclassification", the Apollo Barberini remains significant in the way it further underlined the artistic ideals that Winckelmann championed in The History of the Art of Antiquity (albeit more usually through an emphasis on the male nude as an ideal form).

Glyptothek, Munich

The Triumph of Galatea (c. 1512)

In his 1755 essay, "Thoughts on Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture", Winckelmann wrote, "The imitation of beauty is either reduced to a single object, and is individual, or gathering observations from single ones, composes of these one whole. The former we call copying, drawing a portrait; 'tis the straight way to Dutch forms and figures; whereas the other leads to general beauty, and its ideal images, and is the way the Greeks took...The ideas of unity and perfection, which he [the modern artist] acquired in meditating on antiquity, will help him to combine, and to ennoble the more scattered and weaker beauties of our nature". Winckelmann cited works such as the fresco, The Triumph of Galatea, by Raphael, as the epitome of this style.

Raphael did not model the figures in his fresco on individual persons but presented, rather, an idealized version of human (and animal) beauty. Indeed, the artist had confirmed this reading saying 'Beauty being so seldom found among women I avail myself of a certain idea in my imagination". For Winckelmann Raphael was the paradigm of what a "modern artist" should be. He remarked upon Raphael's composed and graceful expression and the calm and noble demeanour, the precedents for which, he found in ancient Greek sculptures. Raphael, according to Winckelmann, was an artist who had achieved that rare balance between emotion and restraint. For Winckelmann, Raphael's art transcended the mere imitation of nature by elevating the viewer's experience to a higher realm of intellectual and emotional engagement. In Winckelmann's view, this was the hallmark of great art and the reason why Raphael's work continued to be celebrated two centuries after its creation.

Fresco - Villa Farnesina, Rome

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1645-52)

Winckelmann was highly critical of the famed Baroque sculptor, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He saw Bernini's style, which focused on dramatic expressions and complex compositions, as antithetical to the simplicity and restraint he admired in Greek sculpture. The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa depicts Saint Teresa of Ávila in a moment of religious ecstasy, pierced by an angel's arrow, which she described as a divine and physical pain. Bernini's mastery of marble is evident in the delicate rendering of textures, from the flowing drapery of Teresa's robes to the feathers of the angel's wings. The sculpture is also admired for its dynamic movement, emotional intensity, and the skillful use of light and shadow. These artistic "virtues" were, however, the foil against which Winckelmann defined his Neo-Classical ideals.

Winckelmann saw The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa as the very worst of Baroque excess. He argued that Bernini's sculpture was left wanting in the noble simplicity and serene grandeur of Greek art, with the intense expression of ecstasy in Teresa's face and body indicative of Bernini's propensity to prioritize affect over form. As art historian Vivienne Morrell wrote, Winckelmann criticised Bernini "for following nature too closely rather than the ancient statues that he should have learnt from". Winckelmann himself warned that "Young artists should be wary of following Bernini [since] 'nothing earns their applause but exaggerated poses and actions'". And yet, according to Morrell there, was something of a double standard at play in Winckelmann's argument. She writes, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa "contrasts with the Greeks: 'The last and most eminent characteristic of the Greek works is a noble simplicity and sedate [calm, still] grandeur in gesture and expression'. [But what] might seem surprising to us is that Winckelmann finds this particularly in the Laocoon sculptural group" which he admired for their remarkable emotional intensity.

Despite this analytical ambiguity, the SHP remarks that, "The enlightened Winckelmann" had succeeded in bringing "Greek democracy and art in contrast with Roman despotism, heavy baroque art, as well as the superficial and a-political art of rococo". Furthermore, his writing overlapped aesthetic preferences with political freedoms, "as the aesthetic and philosophical superiority of ancient Greek art is inextricably linked to the democracy of [Greek statesman and general] Pericles" who, during the 5th century BCE. instigated a "golden age" of Athenian cultural and intellectual achievement through citizenship and democracy.

Marble - Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Oath of the Horatii (1784)

Academic, Katherine Adelaide Gatty, writes, "The interest in the simplicity of form and revisiting of ancient Greek ideals of beauty was encouraged in France by the early translation and publication of Winckelmann's work on the art of antiquity and the classical ideal, and put into practice by French artists such as Joseph-Marie Vien and his pupil Jacques-Louis David at the Académie de France à Rome". David's Oath of the Horatii is an icon Neoclassical art. The painting depicts a dramatic and moral scene from Roman legend: the Horatii brothers swearing an oath to defend Rome, with their father presenting their swords while their sisters grieve in the background. David's masterful sense of composition, characterized by its clear lines, balanced forms, and austere color palette, underscores the themes of duty, sacrifice, and patriotism. The artwork's stark contrasts and emotional intensity also resonated with the political climate of pre-revolutionary France, serving as a call to civic virtue and unity.

The influence of Winckelmann's writing and the Neoclassical movement, and his concept of "ideal beauty" - or the "beau idéal" as the French critics referred to it - is well documented. But Gatty's research explores a lesser-known dimension to Winckelmann's influence that stems from the German's writings on antique dress and drapery. As Gatty explains, "Winckelmann charted historical periods through costume, demonstrating the way in which he used the superiority of Greek clothing to prove teleologically that Greek art was the best. Winckelmann extended this interest in clothing to providing instructions to contemporary artists on how they could achieve the expressive effect of the fold and the throw of cloth in their own work".

In Oath of the Horatii, David pays meticulous attention to the soldiers' tunics (based on ancient Roman uniforms), the softer clothing of the women, and the drapery covering the seat, creating the contrast between the battle-hardened soldiers and the gentle femininity of the distressed women. In order to achieve the proper anatomical proportions, David painted his figures as nudes before then adding clothing. As Gatty writes, the "ideal beauty in late eighteenth - and early nineteenth-century France was the accurate rendering of the connoisseurly details of costume as emblematic of the concept of Truth, and the expressive and aesthetic qualities of drapery, combined with the perfect form and contour of the nude body underneath. In this relationship between the body and drapery a sense of ideal beauty could be effectively, accurately and appropriately expressed. [The] French artists were able to express the 'beau idéal' within traditional academic conventions and hierarchies of the day and alleviate public unease over the use of nudity".

Oil on canvas - Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

Biography of J.J. Winckelmann

Childhood

Johann Joachim (J.J.) Winckelmann was born on December 9, 1717, in Stendal, a small town in the Prussian province of Saxony-Anhalt. His father, Martin Winckelmann, was a cobbler; his mother, Anna Maria Meyer, was the daughter of a weaver. The Winckelmanns resided in a tiny thatched house that was essentially a single room. His parents would likely have slept in a small alcove, while young J.J. had his own small sleeping area. Despite their dire financial circumstances, J.J.'s parents doted on their son and, with the support of a local pastor, sent him to the primary Latin school in Stendal where he excelled in his studies.

To help pay for his education, J.J.'s parents arranged for their son to join Kurrende, a traveling choir who earned money through live performances. Winckelmann also won scholarships and the support of local patrons to continue with his education. At the age of nine he joined secondary school where he came under the direct influence of the school principal, Esaias Wilhelm Tappert. Winckelmann formed a close relationship with Tappert, taking on the role of his personal assistant and book reader (due to Tappert's badly failing eyesight). Winckelmann showed remarkable intellectual curiosity from one of such tender years. Indeed, he took on the role of supervisor for the school library which allowed him direct access to enlightened English and French authors who ignited his faith in political freedoms. (Winckelmann claimed later that Prussia had been an oppressive state and that living there had taught him "what it means to be a slave".)

Christian Tobias Damm, the School's vice-president, and a specialist in Greek mythology, passed on his love of Homer to Winckelmann. He read the Iliad and the Odyssey (in translations by Alexander Pope) which set in motion his life-long passion for Greek antiquity and laid the groundwork for his later scholarly pursuits. With the backing of Tappert, the eighteen-year-old Winckelmann visited the Köllnisches Gymnasium in Berlin, and the Altstädtisches Gymnasium in Salzwedel, where he studied constitutional theory, natural sciences and Greek language and literature.

Early Training and Work

In April 1738, Winckelmann enrolled on a theology degree at the University of Halle, even though he was not especially concerned with theological matters. He attended lectures by the "father of modern aesthetics", Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, and attended seminars by the physician and philologist, Johann Heinrich Schulze, on Greek and Roman antiquities through the study of ancient coins (numismatics). But it was Baumgarten's emphasis on the sensory experience of beauty, and his establishment of aesthetics as a distinct philosophical discipline, that truly resonated with Winckelmann. His interests soon shifted fully onto classical linguistics and ancient history.

In May 1741 Winckelmann transferred briefly to the University of Jena where he studied medicine. The Society for Hellenism and Philhellenism (SHP) suggests that "His obsession with the exhaustive recording of human body parts as a basis for an artistic analysis of ancient Greek statues i.e. for Apollo Belvedere, is related to his brief, unaccomplished studies in Medicine [at Jena]". The SHP adds that Winckelmann's homosexuality "was a second reason for his obsession with the beauty of the human body, especially the male one".

In 1742 Winckelmann's teaching and writing career began in earnest when he took up the position of Greek and Latin teacher, and Vice Rector, at a private school in Seehausen. It was at Seehausen that Winckelmann experiencing his first love with his pupil, Wilhelm Peter Lamprecht, and with whom he shared a room until 1746. Historian Michael Preston Worley writes "In [his] letters, Winckelmann addressed Wilhelm as 'most beloved brother' and confided to him [...] that he considered their friendship to be without equal in their own century. The young man [...] then left Winckelmann, who suffered an emotional crisis. Winckelmann's intense passion, relentless solicitude, and total dedication to his 'special friends' would have been difficult for almost any adolescent to understand. That summer (1747), Winckelmann expressed to another pupil and sympathetic friend, Friedrich Ulrich Arwed von Bülow, his ardent longing for friendship like that of Orestes and Pylades in Greek mythology, and added later that this passion would be the unique study of his own life. It took another year before Winckelmann could forget about Lamprecht completely".

Goethe wrote that Winckelmann "had reached the age of thirty without once having been smiled upon by fate, yet within him lay the seeds and potential of an enviable destiny". If Goethe was correct, it was in 1748 that Winckelmann began to realize his destiny when he accepted an offer from Count Heinrich von Bünau to move to Schloss Nöthnitz near Dresden to take on the role of librarian. The library, which housed over 40,000 volumes, was a very important private institution and Winckelmann welcomed the chance to further his learning. In his new role, Winckelmann assisted von Bünau on a book on the Holy Roman Empire, and began to formulate his own theories on Greek antiquity and art.

Mature Period

The Pope's ambassador, Alberico Archinto, was a regular visitor to the Dresden library, and it was he who offered Winckelmann the position of librarian at the Vatican. The library was considered the center of world knowledge and Winckelmann happily agreed to a precondition of employment that required him to convert from Lutheranism to Catholicism. Arriving in Rome in 1755, Winckelmann quickly immersed himself in the art and culture of the ancient city, his new status affording him access to important collections and archaeological sites. In respect of the latter, Winckelmann developed a standard scheme for the scientific description of excavations of archaeological sites at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabia. It was in Paestum, meanwhile, that he came across ancient Greek temples for the first time. Winckelmann published his essay "Thoughts on the imitation of Greek works in painting and sculpture" (1755) in which he argued that Greek antiquity was characterized by a "gentle simplicity and quiet grandeur" and implored contemporary artists to adopt these principles as a means of gaining higher learning and new knowledge.

Winckelmann mingled comfortably with Rome's leading scholars, artists, and patrons of the arts, including the German painter Anton Raphael Mengs. Winckelmann loathed the excesses of the Baroque style and tended to view seventeenth-century artists more generally as uninteresting. One exception was Mengs whose "Raphaelesque" work, Parnassus (1761), he especially admired. The art historian Vivienne Morrell writes, "Mengs painted his Parnassus ceiling fresco in 1761 in Cardinal Albani's villa. This depicts Apollo and the muses on Mount Parnassus, with the pose of Apollo modelled on the Apollo Belvedere statue, then so universally admired. Both Mengs and Winckelmann were living at Villa Albani at the time and it is likely each influenced the other. [...] According to Winckelmann, Mengs was the 'greatest painter of his time, and perhaps of all time following. He is risen like a phoenix from the ashes of the first Raphael to teach the world the path to beauty in the arts'". Art historian Thomas Pelzel adds, "Parnassus is among the earliest examples in Neoclassical painting in which we find such extended evidence of the use of figures derived from the ancient paintings of Herculaneum".

While Winckelmann was of affable and sociable character, his private life was marked by a pursuit of secret homosexual relations. In terms of his search for romantic partners, Rome offered a more convivial environment than Northern Europe. As Worley writes, "Throughout Western Europe, authorities preferred to ignore sex offenses between men in order to keep the populace ignorant of the vice, unless it involved running a male brothel or raping a minor. Discretion was the key to survival in the gay underworld. The upper classes, members of the clergy, and intellectual and artistic elites (including Winckelmann) were largely untouched by legal authorities, but the middle and lower classes were still at risk". Indeed, in 1762 Winckelmann fell in love with a young nobleman, Friedrich von Berg, and to whom he dedicated his 1763 essay "Treatise on the Capacity for the Feeling of the Beautiful" ("Abhandlung von der Fähigkeit der Empfindung des Schönen").

Following Archinto's death, Winckelmann became a protégé of Cardinal Alessandro Albani, who appointed him to the prestigious position of Commissioner of the Roman Antiquities in 1763. Winckelmann led high-ranking officials on tours of ancient Rome and was actively involved in the preservation of ancient artifacts. His rare expertise in Classical art duly led to his appointment as the Prefect of Antiquities for Rome and the Papal States (a position once held by Raphael) that allowed him to oversee excavations and the cataloging of artifacts. His incisive studies and descriptions of ancient sculptures, such as those as the Apollo Belvedere (c. 120-130) would become seminal texts in the field of art history. Indeed, Winckelmann helped establish the Apollo sculpture (a copy of an original bronze statue (c. 330-320 B.C.) by the Greek sculptor Leochares) as the epitome of aesthetic perfection. By this time Winckelmann's reputation was growing amongst the public and was confirmed in his honorary membership of numerous leading academies, including the Accademia di Cortona, the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, the Society of Antiquities in London, and the Academy of Göttingen.

Late Period

In 1764 Winckelmann completed his masterwork, History of Ancient Art (Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums). In it, he emphasized the importance of emulating the artistic ideals of antiquity, advocating for a return to classical principles in contemporary art. Winckelmann defined four eras of ancient Greek art and literature: (a) the era of "archaic style" running from the 7th-6th century BC, (b) the 5th century era of the "high style", the apex of the classical era, (c) the era of Praxitelis's "beautiful style", (d) the era of decline of the ancient art and literature. The book would become a benchmark text in art history, offering a different perspective than that offered by Giorgio Vasari in his equally influential biographical studies of Renaissance artists, Lives of the Artists (1550 and 1568). The SHP writes, "The value of [Winckelmann's] work lies in the accurate description of the characteristics of each artistic period. In this way he created a methodological tool for classifying works, not exclusively for the science of classical archaeology. At the core of his work are the impressive and detailed descriptions of the artistic masterpieces". Such was the book's impact, the History of Ancient Art laid the intellectual groundwork for the Neoclassical movement that would soon come to dominate European art.

After the publication of History of Ancient Art, Winckelmann's reputation as the leading authority on classical art was beyond dispute. He maintained extensive correspondence with other scholars and artists, further disseminating his ideas and fostering an international network of intellectual exchange. His writings even became associated with the rise of Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), a German literary movement of the late 18th century associated chiefly with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller. However, this connection seems, on the face of it, a somewhat contradictory association. Winckelmann was a strong proponent of Rationalism whereas Sturm und Drang promoted the idea of human freedom and emotional expression over the "cult" of Rationalism. Nevertheless, the movement dovetailed with Winckelmann's devotion to the "beautiful style" of Greek art and his commitment to human dignity and the struggle for political freedoms. Goethe wrote, "Winckelmann is like Columbus, not yet having discovered the new world but inspired by a premonition of what is to come. One learns nothing new when reading his work, but one becomes a new man!".

In April 1768, Winckelmann decided to return home to Germany to visit friends and institutions he was affiliated with. While crossing the Alps with his friend, the sculptor Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, he fell ill and decided to return to Rome. Cavaceppi escorted him to Regensburg, and then on to Vienna (where he was received by Empress Maria Theresia). Winckelmann then traveled to Trieste where he planned to take a ferry to Ancona (and then onto Rome). With his ship delayed, Winckelmann took a room in a local hotel and, on June 8, 1768, was murdered (probably for coins gifted to him by the Empress) in the room by a local thief, Francesco Arcangeli. (Arcangeli was executed twelve days later) Winckelmann's untimely death at the age of fifty, cut short a brilliant career. In his memoirs, Goethe said that when news reached him of Winckelmann's death it felt "like a thunderbolt in the clear sky", while the German writer, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, (who had previously challenged Winckelmann's ideas) wrote that he would gladly offer Winckelmann years of his own life. In 1822, the Italian sculptor Antonio Bosa designed and built a burial monument in his honor in the San Giusto Cemetery in Trieste.

The Legacy of J.J. Winckelmann

Winckelmann revolutionized the field of art history by combining rational scholarly analysis with emotional responses to sublime visual experiences. In so doing he rejuvenated the aesthetic values of Greek antiquity. By classifying art as distinct historical periods and styles, he established a framework that remains a cornerstone in art historical studies over three centuries on. Moreover, his emphasis on the aesthetic ideal of classical beauty, characterized by a "noble simplicity and calm grandeur", shifted art criticism away from technical and thematic aspects toward the inherent beauty and cultural significance of art. His ideas set the tone for the Neoclassical movement, inspiring artists like Antonio Canova and Jacques-Louis David to reawaken the classical motifs and ideals Winckelmann had done so much to champion.

Winckelmann's ideas extended beyond art and aesthetics into broader cultural and intellectual discourse, too. His advocacy for the superiority of Classical art, and his premise that ancient Greek democracy and freedom nurtured individual and artistic liberty, was taken up by subsequent generations of historians, including those associated with the German Sturm und Drang movement. His idealized vision of Hellenism, moreover, linked the democratic and aesthetic values of ancient Greece with contemporary European ideals, particularly in Germany, fostering a cultural identity that carried over into the nineteenth century. Winckelmann's methodical approach to the classification and historical analysis of ancient artifacts established foundational principles for future archaeological studies. The Society for Hellenism and Philhellenism states: "This great scientist, a man of spirit and intellect, identified ancient Greece and the system of art, culture, democracy and the values that it represents, as the cradle of civilization of the western world. Thus he laid the touchstone for a series of extreme developments in Europe. Neoclassicism, the Enlightenment, Romanticism, and finally, Philhellenism, relied heavily on the work and ideas of this noble man".

Influences and Connections

-

![Anton Raphael Mengs]() Anton Raphael Mengs

Anton Raphael Mengs - Homer

- Plato

- Alexander Pope

- Erasmus of Rotterdam

![Johann Wolfgang von Goethe]() Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe- Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

- Karl Philipp Moritz

- Johann Gottfried Herder

-

![Antonio Canova]() Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova -

![Jacques-Louis David]() Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David -

![Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres]() Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres - John Flaxman

- Bertel Thorvaldsen

-

![Anton Raphael Mengs]() Anton Raphael Mengs

Anton Raphael Mengs - Karl Philipp Moritz

- Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

- Giovanni Battista Casanova

- Charles-Nicolas Cochin

-

![Neoclassicism]() Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism -

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism - Sturm und Drang

Useful Resources on J.J. Winckelmann

- Winckelmann's 'Philosophy of Art': A Prelude to German ClassicismBy Elizabeth Prettejohn

- Winckelmann and the Invention of Antiquity: History and Aesthetics in the Age of AltertumswissenschaftBy Katherine Harloe

- Winckelmann and the Notion of Aesthetic EducationBy Jeffrey Morrison

- Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and SculptureOur PickBy Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- Winckelmann's Images from the Ancient World: Greek, Roman, Etruscan and EgyptianBy Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Edited by Stanley Appelbaum

- The History of Ancient ArtBy Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- Letter and Report on the Discoveries at HerculaneumBy Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann on Art, Architecture, and ArchaeologyBy Johann Joachim Winckelman

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI