Summary of Kitagawa Utamaro

In a relatively short, but prolific, career Utamaro emerged as one of the greatest masters of late eighteenth-century Japanese art. He is associated generally with the Ukiyo-e ("pictures of the floating world") woodblock print technique and he helped define the "golden age" of this centuries-old Japanese artform. Utamaro was, with Hokusai and Hiroshige, one of the three outstanding Ukiyo-e artists of this period. But while his illustrious compatriots gained renown primarily for their landscapes, Utamaro made his name, nationally and internationally, for his slender, graceful, and sensuous, Bijin-ga ("pictures of beautiful women"). His career was not without controversy, and Utamaro's rebellious streak saw him break strict Japanese censorship laws for which he was arrested and punished towards the end of his career. But his ability to portray the personality and private lives of women from all walks of Edo (now Tokyo) life entranced not just Japanese audiences, but Western artists and collectors too. The Impressionist Mary Cassatt said of Utamaro's woodblock prints, "you who want to make color prints, you couldn't imagine anything more beautiful".

Accomplishments

- While he did not create the Bijin-ga genre, Utamaro certainly redefined it with his unique compositions. Previously, Bijin-ga artists had shown groups of women in full-length. But Utamaro filled out his picture frame, often with a single image of his model's upper body. His ability to capture the gestures and detail in feminine beauty showcased Utamaro's deftness of touch, with his delicate portraits of women earning him the title "master of femininity".

- Although Utamaro had experimented with new techniques to render the flesh tones of his women in a softer, more naturalistic, manner, he did not attempt to represent women in their natural physiognomy. Utamaro's women, from mothers, to geishas, to courtesans, are idealized with long elongated and slender bodies and often dressed in finely patterned fabrics. Their heads, which sit on long necks and small shoulders, are always noticeably longer than they are broad, with long noses, and eyes, and tiny "red butterfly" mouths. His work provided a benchmark for future generations of woodblock artists.

- In Paris, Utamaro was venerated (as were Hokusai and Hiroshige) by writers including Charles Baudelaire and Edmond de Goncourt, and artists, including Manet, Monet, and Cassatt. But the most direct comparison can be observed between Utamaro and Toulouse-Lautrec (who himself was an avid collector of Utamaro's prints). Both produced images of prostitutes, but unlike the Frenchman, Utamaro's love of the opposite sex saw him represent his courtesans with the same elegance and poise with which he treated all his women.

- Utamaro's prints were imported into France (following a new trade 1858 agreement between the two countries) where his elegant female portraits were a key influence in the rise of the concept of Japonism. It was a term (coined by French art critic and collector Philippe Burty in 1872) that accounted for to the enormous popularity of Japanese art with many nineteenth century modernists living and working in Paris. To this day, France remains a major European marketplace for Utamaro prints (be they originals, reproductions, or fakes).

The Life of Kitagawa Utamaro

Historian E. H. Gombrich wrote, "Utamaro would not hesitate to show some of his figures cut off at the margin of a print or a bamboo curtain. It was this daring disregard of an elementary rule of European painting that struck the Impressionists. They discovered in this rule a last hide-out of the ancient domination of knowledge or vision".

Important Art by Kitagawa Utamaro

Kushi (Comb)

In this image, a woman peers through a translucent yellow glass comb, which she holds delicately with both hands. She is believed to be the same woman who appears in Utamaro's 1802-03 hand-fan painting Giyaman Oshima (with the title of the work believed to be the name of the woman, probably a popular Edo courtesan). Whereas full-length group scenes had been the norm in Ukiyo-e images for over a hundred years, and while Bijin-ga was a long established generic term for individual pictures of beautiful women, Utamaro pioneered and popularized half-length Bijin-ga portraits. He also experimented with color and printing techniques, resulting in striking images, such as this one in which the vibrant patterned background compliments and highlights the subject's beauty.

Utamaro's earliest images (prior to the 1790s) followed Ukiyo-e precedents (such as prints by artist Torii Kiyonaga) in terms of the shape and proportions of his figures' heads, faces, and bodies. Soon, however, he adopted the Katsukawa school's large-head depictions of actors. Japanese woodblock printing, art historian Woldemar von Seidlitz explains how Utamaro "created an absolutely new type of female beauty". As he describes: "[Utamaro's] exaggerated proportions of the body [reach] such an extreme that the heads were twice as long as they were broad, set upon slim long necks, which in turn swayed upon very slim shoulders; the upper coiffure bulged out to such a degree that it almost surpassed the head itself in extent; the eyes were indicated by short slits, and were separated by an inordinately long nose from an infinitesimally small mouth; the soft robes hung loosely about figures of an almost unearthly thinness".

In a recent discussion, observers such as Japanese filmmaker Megumi Sazaki have "expressed frustration" at not being able to "easily read" the emotions of the women in Utamaro's prints. As woodblock printmaker David Bull explains, "They all have exactly the same shaped nose, and it's always exactly the same-shaped angle," and yes, this "strict set of rules" made it difficult to show emotions in the genre. However, says Bull, "[Ukiyo-e] is a genre that is decorative. I don't see it as having a deep psychological meaning. I just love the beauty of them, as do most people now, we just take them as clean, simple, beautiful, decorative pieces of art. That to me is what Bijin-ga as a genre means".

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper) - Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C

Kachō (Mosquito Net)

Kachō is one of three known prints from Utamaro's Model Young Women in Mist (Kasumi-ori Musume Hinagata) series, though it is possible that there were originally more works in the series. Each work in is a double portrait, with one woman being seen through a translucent woven material (such as a thin silk gauze mosquito net, in this case), and the other woman appearing in front of the screen. Creating the "misty" effect of showing the figure through a woven material required a high level of skill in both the carving and printing stages of the woodblock printing process. In Kachō, the women face each other, as if conversing, while in the other two works in the series Reed-Screen (Sudare) and Summer Clothing (Natsu Ishō), both women face in the same direction.

Art critic Laura Cumming says of these works, "Each print plays upon different kinds of image: silhouette, shadow, reflection, illusion, reality, the eye having to play hide and seek to find the meaning of a scene. [...] Perhaps they are prostitutes, perhaps not. Unlike Toulouse-Lautrec, for example, Utamaro's prostitutes are presented with just as much dignity as his aristocrats. [...] To modern eyes, the distinctions between the two girls [...] are so minimal as to be nearly invisible; a slightly more aquiline nose or less angled eyebrows; perhaps it is true that they are variations on his template of beauty. But this is the essence of Utamaro, in a way: inflections so small it makes one marvel that a whole image can be defined, or redefined, by them".

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper) - Art Institute of Chicago

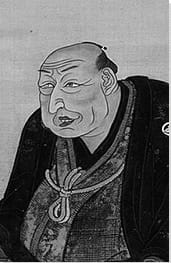

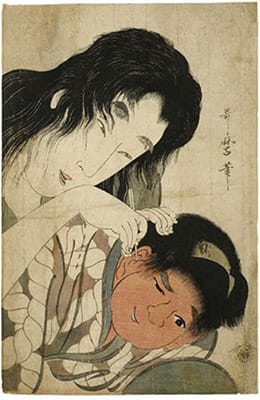

Yama-Uba and Kintarō

Utamaro is also known for his tender depictions of motherhood. He created many such images of unknown, yet presumably "real" mothers and children (as in Mother and Sleepy Child (c. 1790) and Bathtime (Gyōzui) (c. 1801)). He also produced approximately fifty prints showing the well-known Japanese folklore characters (or yōkai, supernatural beings) Yama-Uba (the mountain witch, or mountain wet-nurse) and Kintarō (the "Golden Boy", a child with superhuman strength, who was raised by Yama-Uba, and is traditionally represented with red skin). Prior to Utamaro's depictions, Yama-Uba had always been represented as old, haggard, and somewhat fearsome, with disheveled white hair, a gaunt face, and, in some versions of the stories, with horns and/or a mouth at the top of her head. Utamaro was the first artist to present her as a young beauty (though he makes her recognizable through the inclusion of bushy eyebrows and slightly unkempt hair). Later woodblock artists, like Kunihisa Utagawa, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, and Yoshitoku Tsukioka, followed Utamaro's example in their own depictions of Yama-Uba.

Moreover, while most visual representations of Kintarō (such as those in the format of giga cartoons, which date back as far as the Keian Period (794-1185 AD) and were early antecedents of manga) tend to focus on his adventures with his animal friends and his feats of strength, Utamaro focused on the relationship between the child and his adoptive mother Yama-Uba. Other prints by Utamaro show Yama-Uba nursing Kintarō, tying his hair into a topknot, kissing him, and bathing him. These are Utamaro's most expressive works, and each image shows the complexity of the mother-child relationship, blending humor and intimacy. Over a century after their creation, these works influenced American Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt, as seen in works like The Bath (1890-91) and The Child's Bath (c. 1893).

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper) - Philadelphia Museum of Art

A Wife of the Lower Rank (Gebon no nyobo)

Individual portraits of beautiful women dominate Utamaro's output, as seen in this image of a woman threading a needle, from the series A Guide to Women's Contemporary Styles (Tosei onna fuzoku tsu). Indeed, Utamaro's works (from his group scenes to his individual portraits), had long served as catalogues for women of Edo Japan to keep up with the newest and most popular fashions. However, by the turn of the century, Utamaro's depictions of women had begun to decline in quality, or, as critic Basil Stewart put it, to "lose much of their grace".

One possible explanation for this change is that Utamaro was distracted by grief following the death of his patron and friend Tsutaya Jūzaburō in 1797. Another hypothesis was put forward by nineteenth-century French art critic Edmond de Goncourt, who, in his writings on Utamaro, painted a picture of the artist having had "many adventures with his muses" in the "pleasure districts of Edo", where he "succumbed to the fatal charm of this brilliant 'underworld', until the time when, seduced by the 'tiny steps and hand gestures', his art underlined by excess, he 'lost his life, his name and his reputation'". It is difficult to know, however, from where de Goncourt got this information, and to what extent it was colored by exoticized European notions of "Orientalism" and "Japonisme" of the time.

Art critic Laura Cumming adds that "it would be hard to think of an artist more intent on the opposite sex. Or one who left more images of women working, waiting, arranging their faces, combing their hair, readying themselves for the day's performance (or the night's trade) or simply thinking, feeling, watching. Perhaps the only contender is Degas, who learned from the Japanese master, prizing, and collecting his prints".

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper) - Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

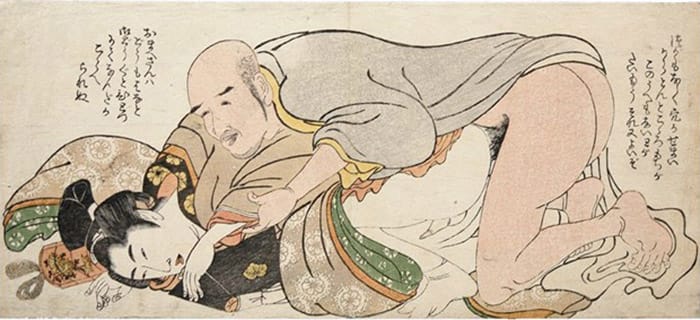

Untitled

One genre that Utamaro worked in, even more so toward the end of his life, was Shunga, which literally translates as "spring pictures", with "spring" being a widely understood euphemism for "sex". Shunga was a type of socially-accepted Japanese erotica, typically produced in the form of Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and enjoyed by men and women from all classes of Japanese society. Works Utamaro produced in this genre ranged from images of clothed heterosexual couples embracing, to gratuitous scenes of partially-clothed or naked couples (male-female and male-male) engaged in mutual masturbation and intercourse (in a range of positions), as well as male clients lubricating male prostitutes, and group sex. In this example, an older, pink-skinned monk is pictured penetrating a younger, completely white chigo or terakosho (a temple pageboy). Both men are exposed from the waist down, with their robes gathered higher up on their bodies. The monk's left hand grips the page's left forearm, and the older man's right arm appears to be either behind the boy's head or around his neck.

The younger male's young age is indicated not only by his more delicate, feminine facial features, but also by his hairstyle. In Japan, a Wakashū (prepubescent or pubescent male) was recognizable by the fact he wore a topknot and had not yet shaved off his forelock completely, at most only a small section at the front. East Asian historian Christin Bohnke notes that the Wakashū (whose age could range from about seven to twenty years), was considered a sort of "third gender" during the Edo Period, and that the standard clothing worn by the Wakashū "were similar to those worn by unmarried young women: colorful kimonos with long, flowing sleeves". Writes Bohnke "Practically every Japanese male went through a Wakashu stage, which ended with a coming-of-age ceremony called genpuku, denoted by changes in clothing and hairstyle. After this ceremony, they would take up their roles as men in society. [...] The prevalence of Wakashu in the woodblock prints speaks to their integral role in Japanese society".

While an image of an older male (especially a monk) "having his way" with a boy reads as shocking to contemporary audiences (as well as to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western audiences), such a scene was commonplace in Japan. East Asian historian Christin Bohnke explains, "Wakashu were connected to sexuality. As youth, they were considered largely free from the burdens and responsibilities of adulthood but regarded as sexually mature. As an object of desire for men and women, they had sex with both genders. The intricate social rules that governed the appearance of Wakashu also regulated their sexual behavior. With adult men, Wakashu assumed a passive role, with women, a more active one. Relationships between two Wakashu were not tolerated. Any sexual relationship with men ended after a Wakashu completed his coming-of-age ceremony. Their most important relationship would be with an older man, which often had both a sexual and a teacher-student element. This was termed Shudō, literally the way of the youth, and a way for younger men to grow into the world through the guidance of a more experienced adult," and monks in particular (as well as advanced samurai) were seen as the greatest experts in the "way of the youth".

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper)

Fukagawa no Yuki (Snow at Fukagawa)

Snow at Fukagawa, lost until recently, is considered the largest Ukiyo-e masterpiece in existence, and is in fact believed to be part of a triptych by Utamaro, along with Moon at Shinagawa (c. 1788) and Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara (c. 1793). The title of the triptych as a whole is Snow, Moon, and Flower, and it was probably created for a wealthy patron in the Tochigi prefecture. Japanese audiences of the time would have linked the title of the triptych to the well-known couplet by ninth-century Chinese poet Bai Juyi, which reads "Snow, moon and flowers - in these moments I think longingly of you". Art critic Lee Lawrence notes that "Here the association extends to geishas and courtesans, glossing over the commerce and servitude at the heart of their professions by mesmerizing viewers with beauty, elegance, artistry, and the possibility of intimacy and romance".

Each work in the triptych depicts courtesans at brothels in three of the most famous Edo districts: Shinagawa, Yoshiwara, and Fukagawa, each during a different season. Lawrence explains that "All three depict Japan's so-called pleasure quarters, but unlike the intimate portrayals of Utamaro's woodblock prints [...] they fill the walls with lively group scenes of courtesans and geishas. Each includes one or more musicians, an amusing incident involving a mischievous child or pet, a décor with ink paintings and other markers of taste, and subtle reminders of what undergirds this world - a glimpse of bedding here, the shadow of a man behind a shoji screen there. Kimonos and obis of brocade, taffeta and silks create cornucopias of colors, patterns and motifs. Willowy bodies sway, lean, bend and pivot as the women share gossip, munch delicacies, smoke long-stemmed pipes, read letters, or marvel at cherry blossoms. Some turn away, revealing pale napes with swallow-tailed hairlines".

These three masterpieces were brought to Paris for the 1878 Expo, contributing to Utamaro's popularity amongst Western artists (especially the Impressionists). Shortly thereafter, the works were separated, with Charles Lang Freer, the founder of the Smithsonian's Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., purchasing Moon at Shinagawa in 1903, Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara passing through the hands of several owners before being acquired by the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in the late 1950s, and Snow at Fukagawa entering a private collection. The latter returned to Japan after WWII and was put on display at the Matsuzaka department store for several days. It then disappeared until 2014, when the Museum of Art in Hakone announced its discovery, though they gave no further details as to where it had been or how it had been found.

Woodblock print (ink and color on paper) - Hakone Museum of Art, Japan

Biography of Kitagawa Utamaro

Childhood

The artist known as Utamaro Kitagawa was born Kitagawa Ichitarō, probably in 1753. His exact place of birth is not known - it could have been Edo (now Tokyo), Kyoto, Osaka, or Kawagoe. The identities of his parents are also unknown, yet some historians speculate that his father may have been a teahouse owner, or possibly even the artist Toriyama Sekien, who tutored Utamaro for many years. This latter supposition is based on the fact that the elder artist wrote of a young Utamaro playing in his garden. This lack of certainty about Utamaro's biographical details continues throughout his life, as no records, letters, diaries, or documents pertaining to his life have been uncovered.

Education and Early Training

Ukiyo-e - literally, "pictures of the floating world" - was an art style that flourished in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867). This period was characterized by hedonism, and Ukiyo-e woodblock prints frequently depicted the pleasure activities of the upper classes, such as dances by seductive courtesans, and kabuki (traditional Japanese theatre and dance performance) actors. The inexpensive print medium made these images available to a mass audience, including those in the lower classes. Nevertheless, artists of these prints often possessed impressive artistic and technical skill.

Utamaro began his artistic career during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, which is now considered the "golden age" of Ukiyo-e. Analysis of his early works indicate that he was influenced by Ukiyo-e master Torii Kiyonaga, who was well known for his tall, voluptuous, graceful, and beautiful women. However, Utamaro's only known teacher was artist, scholar, and kyōka ("wild" or "mad") poet, Toriyama Sekien. It is believed that Utamaro began training with Sekien at a young age, and the master described his pupil as intelligent, talented, and devoted. Utamaro possibly befriended Eishōsai Chōki, another Ukiyo-e artist, who trained with Sekien around the same time.

Utamaro's first known published work is believed to be an illustration of eggplants in the haikai ("comic linked verse") poetry anthology, Purple Japanese Iris (Chiyo no Haru) (1770). Around 1775 he began using the nom de plume, Kitagawa Toyoaki, when he produced cover art for the kabuki playbook Forty-eight Famous Love Scenes. He also produced portraits of kabuki actors. In the early 1780s, he began working with Tsutaya Jūzaburō, the young founder of Edo's Tsutaya publishing house, with his first work for Tsutaya being a kibyōshi (Japanese picture book) created with writer Shimizu Enjū, titled The Fantastic Travels of a Playboy in the Land of Giants (1773).

Mature Period

It is believed to have been at a feast hosted by Tsutaya in the fall of 1782 (where artists Kiyonaga, Kitao Shigemasa, and Katsukawa Shunshō, as well as writers Ōta Nanpo and Hōseidō Kisanji were in attendance) that Utamaro first announced the artistic name he would use for the remainder of his career. Dieter Wanczura, founder of the Artelino auction house, notes that it was common for Japanese artists of this period to use an alias and for artists to change their artist name a number of times throughout their lives. As was customary, Utamaro produced a print especially for the occasion to be handed out to the guests, and the image he created contained a self-portrait of Utamaro bowing before a screen bearing the names of the guests.

Around this time, Utamaro went to live with Tsutaya for approximately five years, and he seems to have been the head artist at the publishing house. Most of his surviving work from the 1780s appears to have been illustrations for books of kyōka poetry. Sekien continued to tutor Utamaro, until the master's death in 1788. By this time, Utamaro had already gained widespread recognition for his skill as an artist, particularly for his elegant portrayal of women. It is known that Utamaro married at some point, though there is no record that the couple had any children. However, throughout his adult life, Utamaro produced several tender, intimate works which featured the same woman and child, with the child growing steadily in age as the years passed (giving credence to the suggestion that he was a father).

In 1791, Utamaro stopped producing illustrations for books, and focused on portraits of women. While most Ukiyo-e artists tended to present portraits of women in groups, Utamaro favored individual, half-length portraits of women from the Yoshiwara district, a famous yūkaku (red-light district) in Edo. This led to speculation that he lived in the Edo area (or perhaps the nearby Bakuro-chō neighborhood), or at least frequented establishments there. The nineteenth-century art critic Edmond de Goncourt wrote that Utamaro's "sumptuous plates seize the imagination through his love of women, whom he wraps so voluptuously in grand Japanese fabrics, in folds, contours, cascades and colors so finely chosen that the heart grows faint looking at them, imagining what exquisite thrills they represent for the artist. For women's clothing reveals a nation's concept of love, and this love itself is but a form of lofty though crystallized around a source of joy. Utamaro, the painter of Japanese love, would moreover die from this love: for one must not forget that love for the Japanese is above all erotic. The shungas of this great artist illustrate how interested he was in the subject". He also produced several volumes of nature studies (plants, animals, and insects), as well as shunga (literally "spring pictures") which was a socially-accepted form of erotica (as the Japanese understood sexuality as a natural part of human behavior).

Late Period and Death

Later in life, Utamaro lived near the Benkei Bridge in Edo. In 1790, a strict new censorship law required prints to receive a censor's seal of approval before being sold, with violators often receiving harsh punishments. This censorship became even stricter over the following years. In 1801 Utamaro produced, Bathtime (Gyōzui), which showed a mother tenderly bathing her child. The Met Museum notes that Utamaro "often took his inspiration from the lives of common people, and he treated the theme of mother and child with more poignancy than did most artists". But in 1804, Utamaro was arrested and imprisoned for three days for his illegal depiction of men from the Japanese Samurai warrior caste in a print series, and for producing an image of daimyō (land-holding magnate) Katō Kiyomasa gazing lustily at a Korean courtesan. In another, he depicted former Japanese ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi holding the hand of his officer Ishida Mitsunari in a sexually suggestive manner, thereby blatantly defying the law forbidding the portrayal of famous political figures (especially if engaged in dubious or unflattering activities). It was a doubly difficult time for the artist who became deeply saddened following the death (in 1797) of his close friend, Tsutaya.

It is known that Utamaro's punishment after imprisonment included being under house arrest (likely handcuffed) for fifty days, though it is unknown if he faced further consequences. It is believed that his punishment caused his health to decline, however, and he passed away two years later, on October 31, 1806. In accordance with Buddhist tradition, he was posthumously given the name Shōen Ryōkō Shinshi. Though he apparently had no heirs, he did have a number of pupils, including artists Kitagawa Tsukimaro, who married Utamaro's widow and began referring to himself as Utamaro II.

The Legacy of Kitagawa Utamaro

When Japanese art found its way into Europe in the nineteenth century, exciting and inspiring Western artists in a craze now referred to as Japonism, Utamaro's striking images of beautiful women, prostitutes, mothers with children, and even erotica, all of which offered new modes of thinking about line, composition, color, and harmony, left a lasting impression on many, such as Impressionists Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, and Claude Monet (who owned more than thirty Utamaro prints), Primitivist Paul Gauguin, and Art Nouveau pioneer Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Utamaro further bridged the gap between East and West by being one of the first Japanese artists to apply Western principles of perspective to his art (as seen in works like Moonlight Revelry at Dozo Sagami (n.d.), Moon at Shinagawa (c. 1788), Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara (c. 1793), and Snow at Fukagawa (1802-06)). Conversely, Utamaro's color compositions, and his more traditionally Japanese compositional formulas (such as his elevated viewpoints) directly influenced modern artist James McNeill Whistler's paintings, such as The Balcony (1865).

The nineteenth-century art critic Edmond de Goncourt wrote, "His delectable images of women fill hundreds of books and albums and are reminders, if any were needed, of the countless affinities between art and eroticism. [...] It is Utamaro's portrayals of women which are the most striking by their sensual beauty, at once lively and charming, so far removed from realism and imbued with a highly-refined psychological sense. He offered a new ideal of femininity: thin, aloof, and with reserved manners". Today, Utamaro's art continues to inspire individual artists, such as Julian Opie, as well as entire genres, like Japanese manga, anime, and hentai.

Influences and Connections

- Torii Kiyonaga

- Katsukawa Shunshō

- Katsukawa Shunkō I

- Tsutaya

- Toriyama Sekien

- Eishōsai Chōki

-

![Claude Monet]() Claude Monet

Claude Monet -

![Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec]() Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec -

![Mary Cassatt]() Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt -

![Julian Opie]() Julian Opie

Julian Opie - Kitagawa Tsukimaro

- Tsutaya

- Toriyama Sekien

- Eishōsai Chōki

Useful Resources on Kitagawa Utamaro

- Utamaro: Portraits from the Floating World (Great Japanese Art)Our PickBy Tadashi Kobayashi

- Kitagawa UtamaroBy Ichitaro Kondo

- Utamaro: Colour Prints and PaintingsBy Jack Ronald Hillier

- Utamaro and the Spectacle of BeautyOur PickBy Julie Nelson Davis

- The Passionate Art of Kitawaga UtamaroBy Shugo Asano and Timothy Clark

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI