Summary of Harry Clarke

Clarke is one of Ireland's greatest, and most controversial, modern artists. Emerging during the later phases of the literary and dramatic movement known as the Irish (or Celtic) Revival, he joined the ranks of literary greats W. B. Yates, J. M. Synge and Sean O'Casey in shaping the international reputation of Ireland as a modern sovereign state. Clarke produced a series of remarkable stained-glass windows and book illustrations that breathed new life into both mediums. His audacious designs placed saints and angels next to sexual and macabre imagery giving his work a uniquely strange and otherworldly feel. His illustrations perfectly complemented works by the likes of Hans Andersen, Edgar Allan Poe and Goethe, while his career, cut tragically short by illness, was capped with his greatest masterpiece of all, the Geneva Window, an eight panelled stained glass celebration of Ireland's greatest modern writers. Though it proved a little too exotic for the conservative tastes of the Irish State and the Catholic Church, the director of Ireland's National Gallery, Thomas Bodkin, said of the Geneva Window that it was quite simply "the loveliest thing ever made by an Irishman".

Accomplishments

- In step with the Irish Revivalist writers with whom he became associated, Clarke was viewed as something of an iconoclast. His early church windows, which most critics agreed rivalled any of the best to be found on the European continent, celebrated early Irish saints and the parts they played in various cults and miracles. This vision was usually at odds with the devotional, Vatican approved, narratives that were at the center of Irish Catholicism.

- In what is almost universally agreed to be the zenith of his short but brilliant career, the Geneva Window, Clarke extended his version of the Irish Revival to an eight-panel montage featuring scenes from the works of Ireland's greatest modern writers. Through the Irish authorities were less than impressed with his romantic vision of alcoholism, slum dwellings, Protestantism, nudity and sexual temptation, the Window helped confirm new Ireland's credentials as an open-minded democracy.

- Clarke's prize-winning success as a student opened the door for a brilliant career as an illustrator. His color and black and white images, which carried the influence the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau and the Vienna Secession, adorned the books of some of the greatest fantasy writers in history. In particular, Clarke's taste for the fantastical and the terrible, which he rendered through distorted human figures, brought him international recognition in his own short lifetime.

- Clarke revelled in his passion for fantastical stories drawn from folklore and modern literature. Reflecting his love of theater and ballet, his stained glass figures were often dressed in luxurious costumes adorned with shimmering sequins and touches of luminous blue, purple, rose, red, gold and silver. His attention to detail was extended, too, to his backdrops which revealed his unique skill at representing natural materials through the medium of glass.

- Clarke illustrations often revealed a playful side to his character. In addition to his damaged and distorted figures, which many saw as interpretations of his own ailing body, he was fond of presenting himself in his work. These unusual "self-caricatures", as seen, for instance in his illustrations of Goethe's Faust, brought a sense of mischief to the otherwise morose imagery.

The Life of Harry Clarke

Summing up the life of his friend's unique otherworldly vision, the Irish Nationalist and mystic writer George "AE" Russell wrote: "Harry Clarke is one of the strangest geniuses of his time" and surmised that he might have even "incarnated from the dark side of the moon".

Important Art by Harry Clarke

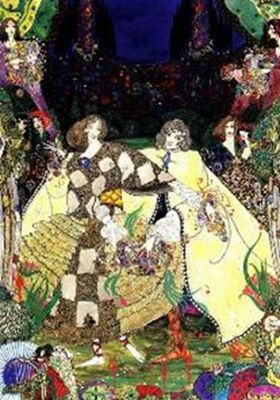

The Garden of Paradise

Following his prize-winning success at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, Clarke was given his first significant book commission by the successful publisher, George Harrap of London. He was to produce 40 full page illustrations, 16 in color, and additional decorative embellishments for both special (some signed and bound in vellum with others boxed and bound in leather or cloth) and trade editions of Andersen's popular fables. The Christie's auction site records that Clarke (who was paid 200 guineas in instalments for the commission) worked "very hard to a scrupulously recorded timetabled routine in London, Dublin and in France [and] completed the job in April 1915. The book was published to acclaim in the autumn of 1916 and ran into a number of subsequent editions, some published by Harraps, others pirated". Christies also records that many of Clarke's original prints were exhibited (and sold) at Brentano's bookstore, Harrap's publishing partner, in New York and that this was "just as well as whatever original artwork by Clarke that had remained in Harraps' London premises was destroyed in the Blitz" (and thus making original coloured illustrations for Clarke's Hans Andersen collection "extremely rare").

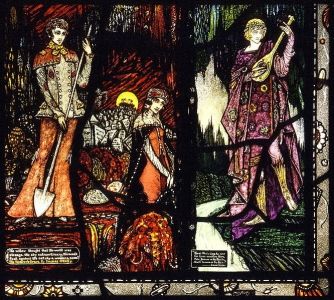

Clarke's illustrations for the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen point towards his career-long penchant for a richly coloured palate and a love of ornamental detail. "The Garden of Paradise" illustrates the tale of a Prince who is lured into the Garden where he encounters a dancing fairy. She is flanked by "the most beautiful maidens, floating and slender, clad in gauzy mist". Clarke decorates the clothing of the figures with exquisite attention to detail; the mosaic, "Klimt-like", patterns coloured in rich reds, blues and dapples of gold helping to distinguish the female figures. The fairy herself is rendered with the whitened complexion and elaborate redhaired coiffure made popular by the Elizabethan miniature, while in the background, an indigo dark night's sky can be made out. If the Prince, who is distinguished by his plain creamy-yellow gown, ignores the fairy's warning not to kiss her he will cause all to vanish into its looming abyss.

Clarke produced many illustrations throughout his short career including single pieces for magazines, and even two rare promotional publications for the Irish whiskey distiller, Jameson. He is also known to have suggested potential future projects to Harrap including Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Huysmans's À rebours, and Bram Stoker's Dracula.

Illustrated book, 16 colour plates and over 24 halftone illustrations - Harrap and Company, London

Saint Gobnait

Between 1915 and 1918 Clarke created nine windows for the Honan Chapel of St. Finbarr, at University College Cork.. Some of those windows produced before 1917 went on show in Clarke's studio where they received rave notices. The Irish Times reported for instance that "the windows, in the opinion of some of the most competent critics, rival in beauty some of most remarkable products of Continental art", while Irish novelist Edith Somerville found them pleasantly shocking within the conservative atmosphere of Ireland at the time: "In a chapel dedicated to the Infernal Deities they should be exactly right, gorgeous and sinful".

The Art critic Tom Walker writes that "The cultural energy and idealism at large in pre-revolutionary Ireland lay behind Clarke's first major commission [for the Honan Chapel]". He cites Ann Wilson's essay on the chapel that "reframes these windows as diverging from Irish Catholicism's earlier 19th-century devotional revolution, which had sought to bring the Irish church into line with Vatican-approved norms [and that the] fantastical incorporation into Clarke's depictions of early Irish saints with their associated cults and miracle stories stands at odds with all this".

The legend of Saint Gobnait involves a fable that tells how she unleashed a swarm of giant bees on a group of unsuspecting robbers. Walker wrote: "giant bees and tiny figures of frightened robbers peering out anxiously behind the blue-robed saint, whose pointed, impassive profile, unnaturally long slim hands and geometrically stylised body give her an otherworldly, non-human appearance". Walker concludes that "For a brief period, such a vision precariously coalesced with Catholic as well as nationalist Ireland", but for Clarke, "[yet] more grotesque and degenerate images [will] start to crop up in the 1920s".

Stained glass - Honan Chapel, of St. Finbarr, University College Cork

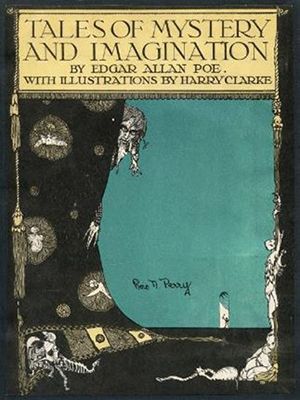

The Colloquy of Monos and Una (Edgar Allen Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination)

While Clarke gained fame in Ireland for his stained glass, it was his illustrations that first brought him international recognition, particularly in the United States. Of the six volumes he illustrated between 1915 and 1931, Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination was the most widely disseminated. The book, first published by George G. Harrap in 1919, contained 8 full-colour plates and 24 black and white illustrations. It was reissued in 1923 with this more ominous cover/dustjacket. Poe's macabre exploration of the human psyche was certainly darker than Clarke's previous illustrations for Hans Andersen's fairy tales (and of course, darker than his various religious commissions).

On the cover for the second edition, a bearded and rugged figure pulls back a stage curtain with his skeletal hand, welcoming the reader to the world of Poe's (and Clarke's) fetid imagination. The stage is empty but for a small door through which a figure can be seen raising a mitre. The image evokes a sense of horror, which is echoed in its symbolist border. It is composed of decaying carcases, larval growths and distorted figures. In his review of Clark's illustrations, his friend and director of Ireland's National Gallery Thomas Bodkin wrote "Mr. Clarke gives full rein to his talent for the macabre, the fantastic and the terrible ... it is safe to predict that no one will ever produce more striking effects in black and white". The critic George Russell thought of Clarke as the ideal interpreter of Poe, and remarked on the closeness of their nature. Indeed, Clarke's capacity for darker work was well known at this stage and would be even more fully realized two years later on his illustrations for Goethe's Faust.

Illustrated book, 8 full-colour plates and 24 black and white illustrations

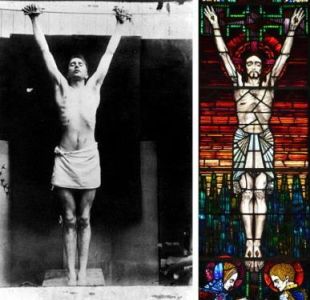

The Crucifixion and the Adoration of the Cross by Irish Saints (The Terenure Windows)

In what was a major commission, Clarke created three stained glass windows for St Joseph's Catholic Church in Terenure, on the outskirts of Dublin City: The Crucifixion and the Adoration of the Cross by Irish Saints (1920), The Annunciation (1922) and The Coronation of the Virgin in Glory (1923). The windows exemplify Clarke's innovative techniques for which he was becoming increasingly well-known by the early 1920s. The Crucifixion and the Adoration of the Cross by Irish Saints was consecrated on May 23, 1920 and is positioned above the altar.

The top panels of the first light depict six golden-haired angels seen praying in profile. The top panels of the central light show five angels attired in gowns of gold and white, with elaborate wings of blue and red while the Holy Spirit, here represented by a dove, sits at the centre of the group. In the main panels, Jesus is shown on the cross, with dividing black lines representing scars, with the lower panel of the central light showing Mary, Saint John and Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross. The top panels of the third light depict six angels dressed in robes of white, blue, green, gold and red. The main and lower panels feature ten Irish saints who kneel in their adoration of Christ. Saint Brigid of Kildare kneels in the foreground in blue robes while she is mirrored by Saint Patrick, who is bedecked in traditional green robes, at the front left panel.

As part of his preparation for the Crucifixion, Clarke turned to photography, recording in his work diary that he spent a day "mucking about and taking photos". Clarke posed semi-naked for his brother Walter as Christ (complete with loin cloth and tied hands) with his own emaciated and gaunt frame matching that of Christ's. The photographs were, in effect, his own self-portraits. Commenting on the "crucifixion" photographs, art critic Philip Hoare suggests that, like Christ, the artist's own body would be ravaged, but in his case "by tuberculosis and the toxic chemicals he used in his art". For Hoare, these "astonishing photographs [...] evoke the terrible vacuum of a Francis Bacon canvas" while adding that it was "as if his body were echoing the psychic [Irish] trauma of famine, revolution and war - as well as auguring the wasting disease [tuberculosis] that would kill him".

Stained Glass Panels - St Joseph's Catholic Church, Terenure, Dublin

The Eve of Saint Agnes (detail)

This is a stained glass window made up of twenty-two small panels and divided into two lights. It was commissioned by the prestigious Jacob's Biscuits family in Dublin and is based on Irish writer John Keats's poem of the same name. In it, Madeline is in love with the forbidden Porphyro, an enemy of her family. According to legend, if she sleeps early on St Agnes's Eve (20 January), and carries out certain rituals, her love will come to her.

The window is testament to Clarke's love for fantastical themes in folklore and literature. Typically, he illustrates the scenes with intricate detail. In Section 2, Panel 3, the so-called "merry revellers" dance to an orchestra. Their headdresses, elaborate sleeves and shimmering sequins illustrate the blues, purples, rose, gold and red referenced throughout Keats's poem. Such was the attention to detail, some scenes are presented as if they were a room in a doll's house. Madeleine sleeps in her bedchamber as moonlight from her own stained-glass window falls across her creating a sort of trompe-l'oeil effect. The room is elaborately furnished. A dainty chair is placed beside the bed. It is draped in a richly decorated blue and silver quilt, complete with hanging tassels. The ornately carved base of the purple bed and its black and gold mattress, just visible beneath Madeline, create a sense of luxury, comfort and romance. The picture detail is further enhanced through the miniature perfume bottles and a casket of jewellery that sit on Madeline's inlaid cabinet (which was based on an actual design by Dublin furniture maker James Hick's). It is testament to Clarke's great skill that he is able to convey the texture of exotic wood through the medium of glass.

Clarke enjoyed using irony in his work. In the frieze of section 5, panel 11, a sinister character holds a dagger (presumably Madeleine's father). To the right of the panel, Porphyro plays a lute. He is oblivious to the characters in pursuit of him. Not for the first time, Clarke presents himself in the work, here he occupies the top left border, staring out to the viewer. These methods bring Clarke's works to life as if he wanted to recreate the spectacle of his beloved theater through the medium of glass.

Stained Glass Panel - The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

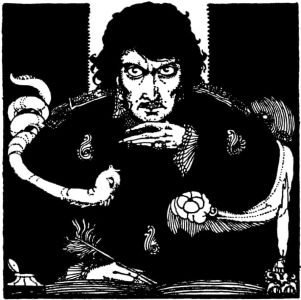

Methinks a million fools in a choir/Are raving and never will tire

Darkest of all of Clarke's illustrations were those for Goethe's Faust. Clarke believed these illustrations to be his best, "full of stench and steaming horrors", while admitting, "I had to laugh at my creations or I would have become morbid". The darkest of these illustrations are hidden in the tail pieces and small designs. Just like his depraved figures who lurk in the borders of his stained glass windows, horrific depictions of faces gnawed by rats, and skewered bodies on a sword, hide as small details in his Faust illustrations.

Many self-portraits are evident in these illustrations. In one instance, Clarke appears as Faust when attempting to free Margaret from her dungeon, in another he even travels with Mephistopheles on horseback. Some caricature-like portraits offer a break from the heaviness of Faust's macabre imagery. A recurring self-portrait is the image of Clarke's eye which is placed in several borders to create a sense of surveillance throughout the book. The decorative motifs surrounding the eye are evocative of the Art Nouveau style. An earlier artist who illustrated Faust in this style was Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910). Comparing the two artists' work, it is clear that Clarke was influenced by Vrubel who used a very similar colour palette and had the same love for decorative art, rich in detail and fantastical themes.

In Clarke's illustration of the witch's kitchen scene the newly young protagonist "stands beneath a canopy of slimy sexually suggestive larval growths sprouting eyes, tentacles and rodent-faces". Critic Tom Walker suggests that "such images of disease and decay" can be linked directly to Clarke's "own doomed struggle with tuberculosis" while elsewhere "in the volume, this darkening shift in sensibility [can be] also traced against the backdrop of the aftermath of the First World War and of conflict in Ireland".

Illustrated book featuring 8 color plates, 13 black and white full page drawings plus partial page drawings - Harrap and Company, London

Mr. Gilhooley/Deirdre (Panel 6) The Geneva Window

Nicola Gordon Bowe, Associate Fellow in the Faculty of Visual Culture at Dublin's National College of Art and Design, writes that in November 1926, Clarke, who had already got wind of the project, received the green light from Ireland's Department of Industry and Commerce to prepare a draft scheme for a stained glass window to be the new Irish Free State's proposed gift to the International League of Nations (ILO) in Geneva. Clarke was, as Rowe points out, "at the peak of his career". Having already surveyed the building earlier that year, Clarke submitted a formal report to the Government on the practicalities and costs for the project. Rowe writes, "As for subject, his recommendation was 'not necessarily' to 'do with labour, but preferably something from the work of a modern Irish writer'". The eight stained glass panels would feature vignettes and citations from fifteen (afore mentioned) twentieth century Irish writers with the intention of adorning the ILO's main staircase.

Sadly, Clarke's Celtic Revivalist vision of modern Ireland, which featured nudity, poverty, prostitution, drinking and dancing, caused great consternation amongst state officials and the Catholic church. For instance, his reference to Sean O'Casey's Juno and the Paycock "celebrated" the life of an alcoholic ex-mariner who struggles to support his family who live in a tenement during the Irish Civil War. The issue of religion was also a cause for disquiet. The Irish population was predominantly Roman Catholic but Clarke's window was dominated by protestant authors. It was this observation that President W. T. Cosgrave was broadly alluding to when he wrote to Clarke suggesting that "the inclusion of scenes from certain authors as representative of Irish literature and culture would give grave offense to many of our people". One such figure was James Joyce whose Ulysses had been banned in several countries for its explicit content, and though Clarke tried to avoid controversy by representing one of his poems (rather than Ulysses), Joyce had long since secured his reputation as a "debauched" lapsed-Catholic who was passionately anticlerical.

It was, perhaps the scenes of nudity and allusions to sexual liaisons, however, that threatened to do most to besmirch the vision of a newly independent Irish state. In this respect, the panel featuring Liam O'Flaherty's (another banned author), Mr. Gilhooley that was the cause of greatest consternation. A stout middle-aged man sits smoking a cigar with a wine goblet in his left hand. He is being entertained by a nude dancer. With her alabaster complexion and dandelion yellow hair, she is swathed in a diaphanous gown of shimmering color and forming the very image of seduction. The promise of sexual pleasure was only reinforced by Clarke who added a quote from O'Flaherty's book: "She came towards him dancing, moving the folds of the veil so that they unfolded slowly as she danced". Commenting on the reclining semi-nude figure from George (AE) Russell's, Deirdre, in the near foreground, meanwhile, Philip Hoare described a "languid female with a blond helmet bob stretches out her pallid body, veiled in diaphanous crimson. Her dead-eyed look would easily find a place in a contemporary avant-garde fashion spread".

Stained Glass Window - Wolfsonian-FIU, Miami Beach

Biography of Harry Clarke

Childhood

Born on Saint Patrick's Day, Clarke was the eldest son of Brigid née MacGonigal and Joshua Clarke, a church decorator who moved to Dublin from Leeds in 1877 to start a decorating business. This business became Joshua Clarke & Sons following the birth of Harry and his younger brother, Walter. The two boys would inherit their mother's respiratory problems, from which she died in 1903. This was very painful blow for young Harry who had been especially close to his mother.

Clarke attended Marlborough Model School, and later, Belvedere College, the same Jesuit college attended by James Joyce some years prior. It is Joyce in fact who provides an insight into Clarke's educational experiences through his novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which describes Belvedere as a place where young boys are terrorized by stories of tortures in hell for those who sinned and especially for those who were sexually prurient. Indeed, the art critic Philip Hoare notes that Harry's "family worried that this influence led to Clarke's 'fascination with the terrors of damnation'". When asked about his father's time at Belvedere, Clarke's eldest son, Michael, told how the priests left him with a "grim understanding of the quality of hell and an idealized version of an improbable Paradise". Despite these formative experiences, Michael added that his father, who was not devout, never decried Catholicism, and while its dogma irritated him, the "deeper mysteries" of religion filled him with awe.

Early Training and Work

On leaving school, Clarke was briefly apprenticed as a draughtsman to architect Thomas McNamara before joining his father's stained-glass business. During his apprenticeship he was tutored by William Nagle, a prominent artist and craftsman in Dublin. He also attended night classes at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. Art critic Tom Walker writes: "At the Metropolitan School of Art [Clarke] took life-drawing classes with William Orpen and was instructed in stained-glass design by A.E. Child. A former assistant of the leading British stained-glass artist Christopher Whall, Child had come to Dublin in 1901; to remarkable effect, he helped conjure Ireland's exceptional Arts and Crafts stained-glass industry, also teaching the likes of Wilhelmina Geddes and Michael Healy". Clarke's skill as an artist and colorist did not go unnoticed and between 1911 and 1913 he was awarded no less than three gold medals by the Board of Education National Competition.

After graduating from the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art in 1913, Clarke won a scholarship to tour France where he studied the stained-glass windows of prominent medieval Churches and Cathedrals. His excursion would have a great influence on his own career, especially his visit to Chartres Cathedral with its magnificent twelfth and thirteenth century widows featuring jewel-like shades of blue, red, magenta, emerald, purple, burnt orange and gold. Clarke became transfixed by the deep blues and ruby reds which he would learn to animate by applying aciding and plating to his finished glass. This effect would become a hallmark of his work.

Clarke looked beyond gothic French Cathedrals as he absorbed the influence of the best of French symbolism, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and the Vienna Secessionists (notably Gustave Klimt). His love for the arts, and his interest in poetry, literature, ballet and cinema, impacted on his stained-glass work and his illustrations. He was also a keen photographer and often produced photographic portraits as a reference point for figures (often in difficult poses) in his window designs.

Clarke's reputation for skill and innovation soon spread amongst Dublin's golden circle of literary, political, legal and artistic figures. Laurence "Larky" Waldron, a stockbroker, Nationalist MP, and Governor of the National Gallery of Ireland and Belvedere College, was part of this group. He would emerge as Clarke's greatest champion. It was he who, in 1913, first commissioned Clarke to illustrate Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Locke though, in the event, Clarke failed to fully complete either project. His illustrations were well received as whimsical and wistful, but some critics accused his work of verging on "boring". Clarke wasn't to be deterred, however.

In October 1914, Clarke married the artist and teacher Margaret Crilly. The couple had met at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art where she was one of the most prodigious pupils of the Irish artist, Sir William Orpen. In the month of his marriage, Clarke was also commissioned to design nine stained-glass windows in the Celtic Revival Style - the Celtic Revival being a literary and artistic movement that began in the 1880s and sought to shape a modern Irish national identity through a revival in the native Gaelic language and ancient folk traditions - for the Royal University in Cork's Honan Chapel. This would prove a key turning point in Clarke's career.

Only the finest craftsmen in the country were commissioned for this chapel, and Clarke insisted on using only the best materials. As it was the height of World War One, some of these materials were not available in Ireland. With the help of his bookkeeper, Miss Sullivan, Clarke had specialised lashed glass, lead and the fluoric acid required for etching, smuggled in from England (apparently concealed in a small leather case). His efforts were rewarded with the Irish Times stating that the Honan Chapel windows "rival in beauty some of the most remarkable products of Continental art", and contemporary Irish novelist Edith Somerville noted that with their "hellish splendour - In a chapel dedicated to the Infernal Deities they should be exactly right, gorgeous and sinful". Somerville's comment was no doubt an allusion to the sinners, thieves and depraved figures that appear amid the intricate designs of the Honan windows.

In the summer of 1915 the Clarkes took a delayed honeymoon on the island of Inisheer, the smallest Island of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. The Island was a special place for Clarke who had spent many previous summers there with his friends from the Dublin Metropolitan School. As the art critic Philip Hoare writes, Clarke "spent six summers, often with his friend, the artist Austin Molloy, on Inisheer [...] where he dressed in a white felt báinín suit made from the wool of local sheep and wore peculiar red raw-hide shoes called pampooties. He might have been a faun in a design for [founder of the Ballet Russe] Diaghilev by [costume designer] Leon Bakst".

It was a location proved to be inspirational for Clarke's work. While he is not noted for his landscapes (as other stained-glass artists such as Louis Comfort Tiffany are) his work is often adorned with minute blossoms and creatures that symbolize the beauty of nature. Indeed, Tiffany's work focused his windows on a natural scene such as a willow tree, whereas Clarke worked much more in the mode of a symbolist. He used elements from nature rather to represent certain attributes, such as purity, love, innocence and peace. Inisheer's flora, fauna and marine life inspired many of these natural motifs in Clarke's work.

Also in the summer of 1915, Clarke's younger brother Walter married Margaret's sister Mary, and the two couples would remain close. Harry and Margaret had three children and led busy lives, Margaret becoming an established artist of Royal Hibernian Academy status, and Clarke's stained glass commissions growing in number. But Hoare suggests that Clarke may have been leading a double life and that his biographies "do not extend to the issues [of his sexuality] raised by his work". As he says, Clarke married and had three children "Yet the queerness in his work seems startlingly explicit, hiding in plain sight: in convents and chapels, in popular publications and in his [own] dandified performance. Given the fate meted out to Oscar Wilde, his fellow countryman, Clarke might have hesitated to transgress too far. But it could hardly be possible to make a more public statement than he did. His gloriously strange vision still bursts triumphantly through those leaded windows". Though Hoare's observation is no more than informed speculation, his close friendship with the famous gay English/Irish stage actor Michaeál Mac Liammóir, with whom he socialized away from Dublin on the London's West End theater scene, may have helped feed this suggestion.

In London, meanwhile, Clarke joined the prominent publisher George G. Harrap. Shocked that Clarke's first publisher had not retained his services, Harrap commissioned Clarke to illustrate The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen. It would be his first completed work and featured a mix of color plates and black and white illustrations. Before the decade was out, Clarke contributed similar content for Edgar Allen Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1919) and an anthology of modern poetry, The Years at the Spring (1920). During these years, J. Clarke and Sons Studios had become incredibly busy and Clarke would occasionally help his father with important commissions before he himself became manager of the Studio's stained-glass division on his father's passing in 1921.

Mature Period

The 1920s was the most prolific period of Clarke's career. He produced more than 130 stained glass windows with some of his most important works coming during this time. He produced three windows - The Crucifixion and the Adoration of the Cross by Irish Saints (1920), The Annunciation (1922) and The Coronation of the Virgin in Glory (1923) - for St. Joseph's Catholic Church, in Terenure, Dublin with the Annunciation winning first prize at the Aonach Tailteann Art Exhibition and Celtic Revival Festival.

In 1924 Clarke completed The Eve of St Agnes, a window which earned him great acclaim. Indeed, in 1925 he was given the great honour of being elected an associate of the Royal Hibernian Academy. During this golden period, Clarke divided his time between Dublin and London. In London his favourite pastime was to visit the theater and the Ballet Russe. The Diaghilev ballet was his favourite and the exotic costumes of the dancers, designed by Léon Bakst, would directly influence his work. Clarke cut a dapper figure on the London theater scene. While attending performances at the Alhambra Theatre in London, for instance, he made the acquaintance of the actor Michaeál Mac Liammóir who later remarked on how exquisitely Clarke was turned out, commenting specifically on his tall and slender frame, his dark good looks and his immaculate formal attire.

The first quarter of the twentieth century is also considered a golden-age of gift-book illustration. Adding to his previous commissions for Harrap, Clarke illustrated Charles Perrault's Fairy Tales of Perrault in 1922 and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's great masterpiece, Faust in 1925. His work for Harrap was of such quality it would see him ranked next to other master illustrators of the period including Arthur Rackhan, Key Nielson and Virginia Frances Sterrett. His other important commissions during this period included a set of illustrations for Ireland's memorial Records in 1914-18 for Maunsel and Roberts Ltd. in 1923, and two sets of illustrations, A History of a Great House (1924) and Elixir of Life (1925), for Jameson's of Dublin whiskey distilleries.

Next to the "frivolous" commercial designs for Jameson's, Clarke's other illustrations were becoming darker; full of macabre imagery and increasingly controversial. His illustrations for Faust, for instance, carry scenes of death and decay as well as erotic imagery. These dark and sexual tendencies also seeped into his stained-glass commissions, although with religious commissions he was rather obliged to work with a greater sensitivity.

By the mid-1920s, Clarke's work was being ranked among the international masters, such as Tiffany, Burne-Jones and the medieval colourists. He had significantly changed the style of stained glass work in Ireland which, before Clarke, had consisted of mass-produced panels of poor quality that were imported from Europe, primarily Munich, Birmingham or London, and assembled in Ireland. His links to the Celtic Revivalists helped to distinguish his style. Indeed, Celtic motifs swirled through his work which, already considered exotic in Ireland, carried the Celtic theme around the rest of the arts and crafts world.

Late Period

In 1926 the Irish Government commissioned Clarke to create a window for the International Labour Building in Geneva. The Geneva Window was to become Clarke's most famous, and most controversial, commission. Nicola Gordon Bowe, Associate Fellow in the Faculty of Visual Culture at Dublin's National College of Art and Design, describes how "Clarke visited the suggested staircase site outside the Deputy Director's room in the International Labour building in April 1926, just after his 37th birthday. He did this on his way back via Paris and London from a convalescent trip to Tangier and Spain arranged by his friend, the writer Lennox Robinson". Clarke had been suffering from exhaustion following a "heavy schedule of stained glass and graphic work [and] his health (his eyes in particular) had been suffering".

Bowe adds that "While preparing to escape to London in January 1926 from the pressures of running the church-decorating studios he ran with his brother Walter in Dublin's North Frederick Street, he had fallen off his bicycle, resulting in serious injuries [but] by the time he reached Geneva, he felt reinvigorated, excited by the prospect of such a prestigious international commission, and was soon back at work in Dublin".

The eight-panel window was to feature vignettes representing the work of 15 twentieth century Irish writers: Padraig Pearse, Lady Gregory, G B Shaw, J M Synge, Seumas O'Sullivan, James Stephens, Seán O'Casey, Lennox Robinson, W B Yeats, Liam O'Flaherty, George AE Russell, Padraic Colum, George Fitzmaurice, Seamus O'Kelly and James Joyce. While there was (and is) general agreement that the Geneva Window was Clarke's great masterwork, the project was poised to go down in Irish cultural history as one of its most ill-fated ventures. As Bowe describes it: "On 17 March 1929 [Clarke] was admitted to a Swiss sanatorium in an attempt to arrest advancing tuberculosis in both lungs. He entrusted the final stages of the window to his studio artists, with whom he corresponded during the fourteen long months he remained away. On his return in May 1930, he could at last complete the window himself, and have it 'mounted in a specially constructed frame' for viewing in early September [...] But disaster was about to strike. By 30 September 1930, the President's objections to the 'subject matter of certain of the representations' illustrating 'scenes from certain authors... as representative of Irish literature and culture' had gathered momentum".

The panels representing the work of Joyce and O'Flaherty, for instance, were considered licentious and decadent by the Catholic church and generally detrimental to the image of the new Irish State. Government officials did visit Clarke's studio but as elections approached the First President of the Irish Free State, William T Cosgrave, declared that the work might "give grave offence to our people" and worried that the government might sacrifice votes from influential groups, in particular the Catholic church, if the offending window was sanctioned. No final decision was reached, however, and the fate of Clarke's career-defining masterpiece hung in the balance.

In July 1930 Clarke's brother, Walter, died from pneumonia. This tragedy, coupled with the pressure of completing the Window, led to a relapse in his own health and Clarke was forced to return to the Swiss sanitorium in October. Bowe writes that he left for Davos leaving instructions that "any Geneva-related correspondence should be forwarded to him" but that this left "the window in the studios, its future unresolved". She describes how he "wrote anxiously to Cosgrave [...] enquiring about the government's decision, but two days before the cabinet's New Year decision requesting the studios to set up the window's panels for further consideration, Clarke died, on 6 January 1931, still in Switzerland".

The Geneva Window was rejected and Clarke's widow, Margaret, was offered the work at the price of Clarke's original commission. Following her death in 1961, the window was loaned to the Dublin Municipal Gallery of Modern Art between 1963-1980 but was removed by Clarke's two sons when the Window was put into storage. The Geneva Window was then sold for a sum "in excess of £100,000" to the Wolfsonian Foundation in Miami, Florida where it is proudly displayed to this day.

The Legacy of Harry Clarke

During his life, Clarke created over 150 windows and a number of panels for churches and private establishments in Ireland, England, the USA and Australia. The distinctive jewel-like appearance of his windows; his dazzling use of color in both glass and illustration, helped widen and elevate the aesthetic influence of both mediums. W B Yates called Clarke "Ireland's greatest artist in stained glass" while George ("AE") Russell referred to Clarke as "one of the strangest geniuses of his time"; a man who might very well "have incarnated here from the dark side of the moon".

In assessing his legacy, Philip Hoare called Clarke a modern artist "at the heart of the nascent Irish Free State, negotiating the secular and the sacred at a time when the twin powers of state and church collided and colluded". Yet within the darkness, Clarke's work was "Ethereal and beautiful and, in its wit and contemporaneity, strangely compassionate"; an art that reflected an Irish society "much more cosmopolitan, sophisticated and aesthetically aware than has normally been acknowledged".

The art critic Tom Walker agreed, writing, "It is clear that Harry Clarke and his chosen media - stained glass and book illustration - are now central to any sense of early 20th-century Irish art, while Lennox Robinson, wrote on Clarke's death that his art would live on for "our generation, and for generations to come", and said of his colors, "They will shine and glow; those blues and reds - how he loved blue! - an inspiration to the faithful".

Influences and Connections

-

![Gustav Klimt]() Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt -

![Mikhail Vrubel]() Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel -

![Aubrey Beardsley]() Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley - Edmund Dulac

- Kay Nielsen

- Austin Molloy

- George William Russell

- Laurence Waldron

- Michaeál Mac Liammóir

- Sean Keating

-

![Art Nouveau]() Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau -

![Art Deco]() Art Deco

Art Deco - Irish Revival

- French Symbolism

- P. Craig Russel

- Austin Molloy

- George William Russell

- Laurence Waldron

- Michaeál Mac Liammóir

- Sean Keating

Useful Resources on Harry Clarke

- Dark Beauty: Hidden Beauty in Harry Clarke's Stained GlassBy Lucy Costigan and Michael Cullen

- Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry ClarkeBy Lucy Costigan and Michael Cullen

- Harry Clarke: The Life & WorkBy Nicola Gordon Bowe

- Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish StateBy Angela Griffith, Marguerite Helmers and Roisin Kennedy

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI